Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Inquiry Written Report - Brianna Sherin

Uploaded by

api-479192510Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Inquiry Written Report - Brianna Sherin

Uploaded by

api-479192510Copyright:

Available Formats

INQUIRY WRITTEN REPORT

How does the use of the Gradual Release of Responsibility model in reading

and viewing support students in providing evidence and justification in their

writing?

NAME: BRIANNA SHERIN

ID: 110200107

DEGREE: Bachelor of Education (Primary/Middle)

School of Education

Division of Education, Arts and Social Sciences

University of South Australia

OCTOBER 2019

1 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Introduction

The Practicum school is an R-7 school located 24km North East of Adelaide in the suburb of Golden

Grove. The Primary school is under the Government school sector and of a category 7. The school was

first established in 1992 in houses at Keithcot Farm Primary School with approximately 90 students.

As of 2019, the primary school currently holds 716 students, along with 39 teaching staff, and 19 non-

teaching staff members. Within the school 51% (364) of students are female, and 49% (352) are male.

According to the school context, 1% of students identify as Aboriginal, and 9% have a language

background other than English. Thus, making its diversity quite minuet. Out of the 10,235 people who

live in the suburbs of Golden Grove, according to the 2016 Census, only 0.8% identify as Aboriginal. In

Golden Grove State Suburbs 86.4% of people only spoke English at home. Other languages spoken at

home included Polish 0.8%, Mandarin 0.8%, Italian 0.7%, Spanish 0.6% and Punjabi 0.6% (abs, 2016).

Drawing upon class context, within the composite year 6/7 class there are 29 students, with 13

females and 16 males. Cultural diversity makes up a small percentage of not only the suburbs of

Golden Grove, but also the ethnicity backgrounds within the class. Two of the 29 students have family

members who speak Punjabi which accounts for 0.02% and one EALD student who is of Polish decent.

The primary school provides a safe and supportive environment where students are consistently

challenged to achieve their best. The school community aims to ‘Open Doors to Unlimited

Opportunities” and uphold the values of R.E.S.P.E.C.T. (Resilience, Excellence, Self-Management,

Perseverance, Empathy, Courage and Teamwork) that underpin all aspects of teaching and learning.

My inquiry research involves engaging the students with effective questioning and feedback

strategies through exposure to a multitude of text genres using a constructivist approach where the

overall goal is for students to make meaning and demonstrate justification through their responses to

literature. The school’s moto allows me the opportunity to support and uphold the values of the

school to ensure that students are successfully engaging in authentic learning experiences that follow

the acronym, R.E.S.P.E.C.T.

Literature Review

Throughout my Practicum, I will be analysing and examining how the following question impacts

student learning outcomes during the process of an action research inquiry: How does the use of the

Gradual Release of Responsibility model in reading and viewing support students in providing

evidence and justification in their writing?

Questioning will functionally improve the outcome of student learning and their ability to

comprehend and infer different texts from a teacher modelled approach to independent student

work to create competent independent learners. Hence, by adapting the use of the Gradual Release

of Responsibility Framework by Pearson and Gallagher (1983) it allows the “teacher to focus on

scaffolding students’ developing skills or knowledge through questioning, prompting, and cuing”

(Fisher & Frey 2013, p.39). The gradual release of responsibility instructional framework purposefully

shifts the cognitive load from “teacher as model, to joint responsibility of teacher and learner, to

independent practice and application by the learner” (Pearson & Gallagher 1983, p.11). It specifies

that the teacher moves from assuming all the responsibility for performing a task to a position in

which the students accept all the responsibility. This gradual release may occur over a day, a week, a

2 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

month, or a year. During the ‘We do’ phase, the teacher motivates students by generating interests

through guiding questions or eliciting questions from students to help gage their understanding of the

topic and where the unit of work may follow. E.g. student interests may guide the following activity,

or this interaction may allow the teacher to enhance and reflect on pedagogical practices to create

successful learning. The guided instruction process should be “thought as a flowchart (Frey & Fisher

2013, p.41). When one scaffold does not work, we move onto the following. When the scaffold works,

we return to questioning to “check for understanding or to probe deeper about students’ knowledge”

(Frey & Fisher 2013, p.41). During guided practice, the teacher should ask: What does this child’s

answer tell me about what he knows and doesn’t know? Questions that “check for understanding are

very important during guided instruction, but questions that uncover errors and misconceptions are

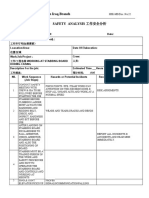

essential”. (Frey & Fisher2013, p.41). Following Frey & Fisher’s (2010) instructional decision- making

tree framework (Refer to Figure 1) allows educators to question and prompt carefully and

strategically to elicit appropriate answers from the

students. As well as hold a substantial collection of

evidence on students understanding to either revert

back to the ‘I do’ modelling phase or move on to

collaborative group practice or independent study. In

order for students to show justification through their

written work, they must be prompted with a series of

questions which scaffolds their ability to comprehend a

multitude of written and visual text types. Thus, as

students immerse themselves in the study of Fantastic

Worlds in a writing unit, they are “reflecting on ideas

and opinions about characters, settings and events in

literary texts, identifying areas of agreement and

difference with others and justifying a point of view” Figure 1: Fisher & Frey Tree Frame (GRR)

(ACARA ACELT162, 2016). In doing so, students

respond to a series of texts through thoughtful questioning and class and peer discussions to develop

justification of fictional and film texts.

To engage learners in cognitive or metacognitive work and to think critically about texts in order to

respond with justification, prompting will be used as a hint or reminder that encourages students to

do the work when they have temporarily forgotten to use a known skill or strategy in an unfamiliar

situation. Incorporating these pedagogical practices into my teaching, I am doing so to create thinking

and new skills. This may be prompted through accountability and formative assessment strategies

which strongly use questioning such as hover and chin it, feedback, exit cards and coral reading to

help students remember key concepts and transfer them into their long term memory in order to use

these new found skills during their writing assessments or tasks. Frey & Fisher (2013) speak of

reflective prompting as a way of developing students’ metacognitive function to stimulate thinking for

purpose of determining the next steps or the solution to a problem. For example, if the learning

intention is to understand and identify the textual conventions of Modern Fantasy during textual

analysis task of Shrek; When a student’s writing does not include evidence, as the assignment

required, the teacher may reply with “What are we learning today? What was our purpose?”

According to AITSL (2018) effective use of questioning helps to “understand where students are in

their learning, and to inform instructional decisions on where they are going to next and how to get

3 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

there” (AITSL 2018). Questioning can be used to prompt students to think about what is being taught

and to give the teacher information on where students are up to in their learning. This allows

educators to adjust instructions to meet learning needs, and support students to progress towards

their learning goals. Throughout learning experiences, students can develop misconceptions. Hence,

teachers must find intervention strategies to help understand and find out what students know or

believe at a point in time. The “primary purpose of questioning should be to find out what students

need to be taught next” (AITSL 2018). Another purpose is to teach students to think critically through

questioning; requiring deeper analysis rather than a simple yes or no or recall of information.

Teachers have long used questioning strategies to review, to check on learning, to probe thought

processes, to pose problems, to seek out different or alternative solutions, and to challenge students

to reflect on critical issues or values they had not previously considered (William 1987, p.13). Hila

Taba (1969) pointed out, that teacher directed questioning leads students to the expected level of

response, thus controlling the students thought or response pattern. For example, when the teacher

asks the student for the characters within the film Shrek, this calls for only the recall of previously

learned information. In contrast, if the class were studying the different archetypes within the film

and the teacher asked one student, Which character is portrayed as the hero archetype within the film

Shrek? And how can you justify your answer? This would be an open-ended question that would allow

the student to formulate a response in a multitude of ways with varying levels of thought process, all

of which could be appropriate responses. Asking students open-ended questions is one of the best

ways to foster more talk about writing in your classroom (Power 2019, p.5).

Methodology

3.1 Action research

All practitioner research or action requires its participants to “to engage with both theoretical and

practical knowledge moving seamlessly between the two” (Groundwater-Smith and Mockler, 2006,

p.107 sited in McAteer 2014, p.6) Action research requires not only the critical reflection on practice

and theory, but is also entitled to ongoing and evolving action within the process. McAteer (2014)

states that without the approach of questioning breath, our engagement with concepts and processes

as educators can remain at a relatively “superficial level” (McAteer 2014, p.2). Research further

suggests that research by teachers can have a positive impact on “the learning of the pupils in their

classrooms (Menter 2011, p.14). Hence, undergraduate students participating in action research

inquiry in preparation for the education profession aids them with the basic understanding of

research concepts and methodology, “along with the ability to read and interpret current research”

(Lambert 2012, p.75). Within education, the main goal of action research is to “determine ways to

enhance the lives of children” (Hine 2013, p.152). Simultaneously, action research can enhance the

lives of professionals who work amongst the educational system. To illustrate, “action research has

been directly linked to the professional growth and development of teachers” (Hine 2013, p.152).

Action research helps teachers grow new knowledge related to their classrooms, it “promotes

reflective teaching and thinking” (Hine 2013, p.152), builds teachers’ pedagogical practices and

repertoire and reinforces the link amid practice and student achievement.

3.2 Case study

Using a case study as a methodology allows the researcher to liken the “advantage and potential

window into rich and enhanced insights about practice” (Mentor 2011, p.55). Hence, using

quantitative and qualitative research methods to measure, interpret, contextualize, identify patterns

4 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

and gain in depth insight on specific concepts or phenomena provides the researcher to categorize

key findings by using quantitative data analysis methods to succinctly measure key findings and the

discovery of new theories and ideas.

3.3 Research questions

Inquiry focus question: How does the use of the Gradual Release of Responsibility model in reading

and viewing support students in providing evidence and justification in writing?

Key questions:

▪ How can I affectively provide feedback to my students to improve student outcomes in

English?

▪ I will I use the Gradual Release of Responsibility Framework to support self- reflection and

student learning?

▪ How will I measure formative assessment strategies embedded into my pedagogical practice

to record student growth data?

▪ How will I fairly measure students personal view- points and justification of different text

types through written response?

3.4 Participants

3.4.1 Case 1

Case study student 1 is a Year 7 student who is twelve years of age. Case study student 1 is diagnosed

with a learning condition called Dysgraphia. “Dysgraphia is a specific learning disability that affects

written expression” (SPELD Foundation 2019) and with placing thoughts onto paper in written form.

They visit an OT, Speech Therapist and attend Equine Therapy to build confidence and self- esteem

Through observation, and professional conversation with my supervising teacher, case study 1 shows

a lack of attention to detail within their written work; which demonstrates basic comprehension and

justification of evidence within work samples. However, their narratives and information reports

which were typed using ICT demonstrated a satisfactory understanding of the criterion given (Refer to

Appendix C). Through informal conversation with the student they show interest in, manga books,

computers and gaming. Case study 1 does not receive additional time with an SSO. However, in class

they may receive one on one time with the teacher to provide prompting and scaffolding during

assessment pieces. Case study 1 would benefit from pedagogical practices that build independence

and accountability in order to provide evidence and justification in response to a variety of literary

texts to create cohesion in their written work. Through conversation with my supervising teacher, it

was stated that case study 1 uses their learning disability to their advantage to get out of work and

suggested to always refer to learning intentions to create student accountability to ensure they

complete their work to a satisfactory standard.

3.4.2 Case 2

Case study student 2 is a Year 6 student who is eleven years of age. Case student 2 is a higher

achieving year 6 student who excels at a year 7 level. Through observation, this student is a high

achiever who possesses great work ethic in completing all tasks to the best of their ability. This was

vastly displayed in their biography (assessments conducted prior to my practicum) where their work

demonstrated fluency and cohesion of sentence structure, punctuation and grammar. They are

5 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

creative, organised, resilient, and show excellence in reading which has demonstrated their ability to

infer texts well during probe reading assessments and they are a capable individual worker. However,

case study student 2 although possesses the knowledge to participate in class discussions, they

portray a quiet nature and avoid contribution at all costs due to lack of confidence and self-esteem. I

believe, that by incorporating the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model: (shared and guided

practice), case 2 will benefit from strategies guided by the teacher such as hover and chin it or calling

upon students randomly by a deck of cards to demonstrate student accountability. By contributing to

these vital discussions during Writing lessons, this student will benefit from stepping out of their

comfort zone by not only having to contribute to discussions, but further justify their responses to

text which in all may prove helpful for other as well to show growth in their proximal zone of

development.

3.5 Data Collection

3.5.1 Methods

Rationale for your chosen methods: Robin Ewing et al. (2014) states that “in some ways data can be

seen as pieces of a puzzle that need to be put together in order to form a picture” (Ewing et al. 2014,

p.378). In order to effectively analyses data and create change to make informative decisions based

around your own pedagogies or student learning/ outcomes, data must be well conducted, formative

evaluation (Ewing et al. 2014, p.379).

Data collection- Beginning: Drawn from observation, the students have limited skills in

comprehending a multitude of different text genres which decreases their success rate of becoming

successful writers. Whilst introducing archetypes, I plan to collect data via photographs of student’s

individual whiteboards. Using the technique of open questioning through the strategy ‘hover and chin

it’, this allows me to formatively assess student’s prior knowledge and skills to gage whether students

are using higher order thinking strategies to predict and create written responses appropriate to the

question. Photographs ensure that “correct answers are a result of genuine student understanding,

rather than an application of naïve / simplistic rules that will not work for more complex questions”

(AITSL 2018, p.5).

Data collection- Middle: During the phase 2, students will complete a summative assessment on a

chosen character; creating an archetype banner to gage my understanding of what these students

need to hone in on prior to the end of unit assessment piece. Along with the use of exit slips to

demonstrate how well students can respond to literature through reading and viewing in answering a

specific question and providing a justifiable answer that provides evidence of understanding. Exit slips

provide the opportunity to “take time to think deeply, authentically, and reflectively, is perhaps more

important than ever” (Leigh 2012, p.189).

Data Collection- End: Students final summative assessment piece is to respond to the text Shrek and

respond to a series of questions that require critical thinking, inferencing skills and justification. Along

with analysing a multitude of traditional archetypes in response to the modern archetypes delivered

in Shrek through a justification table (Refer to Appendix E). This allows me to develop further

understanding whether prompting students with questions using the Gradual Release of

Responsibility Model has developed students higher order thinking skills in creating new strategies to

respond to literature appropriately with succinct and justifiable answers within their writing.

3.5.2 Data sources (Refer to Appendix E)

6 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

3.5.3 Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations are a major element of research. The researcher needs to promote the aims of

the research conveying authentic knowledge, truth and prevention of error. The researcher should

collect responses from the participants related to the inquiry. Hence, the researcher should avoid the

use of dishonest material to ensure accuracy. Along with maintaining confidentiality of the responses

of the participants involved to ensure privacy of subjects. Thus, the use of codes should be used to

disclose personal information.

3.5.4 Analysis

To successfully analyse student data, I will use a two tables with student’s names vertically down the

margin and record student findings of both formative and summative assessment strategies such as

exit slips and the traffic cone system using a colour coded key (red, yellow, green OR a tick, dash,

cross) using a “frequency distribution table: this contains the distribution of the frequency across

cases for the same variable” (Menter 2011, p.56)

To also map out student progress I used a self-reflection table which will allow me to record student

findings, make observations, reflect on my own pedagogical skills and supervising teacher comments.

Hence, this data allows educators to evaluate, adapt or change their strategies to ensure they meet

the needs of their students. The Australian Professional Standards for Teachers establishes that

graduate teachers and beyond must be expected to assess student learning and provide clear

feedback to students on their learning. Feedback can help educators to improve their pedagogies and

students to become more successful in all areas of their learning, in particular; writing skills.

Reflection allows me to look at “how am I going? And where the learner is right now. Finally, Where

to next? And how to get there” (Black & Wiliam 2009 & Hattie and Timperley 2007 sited in AITSL

2018, pp.7-8).

Findings - 4.1 Case 1

During my two lead in days upon my arrival of my Practicum, in order to plan authentically,

appropriately and successfully I staged observations that allowed me to hone in on the interests of

the students and how they learn. Conducting professional conversations with my supervising teacher,

and sharing the various findings that I had found based upon shared reading sessions and informal

conversations; case 1 would become the first candidate to investigate the question ‘how does the use

of the Gradual Realise of Responsibility model in reading and viewing support students in providing

evidence and justification in writing?’ As stated above, case study 1 has been formally diagnosed with

Dysgraphia; finding it hard to scribe and process information quickly and effectively in order to

communicate their comprehension of texts through written justification.

Within my initial lesson, I wanted to gage how case student 1 performed best using a multitude of

strategies to make formative decisions to construct appropriate pedagogical strategies that would

create student success. Upon initiating the first lesson where I introduced ‘Fantastic Worlds’ to the

students, I used a strategy called ‘hover and chin it’. Hover and chin it is a form of formative

assessment where students are guided by a question and must explain or justify their answer;

hovering the board close to their chest to ensure it is their own work until they are asked to chin their

7 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

whiteboard in order for the teacher to see. It’s a form of oral recognition to check where students are

at and whether or not content needs to be retaught differently. During this initial lesson, I looked at

traditional archetypes and how we can classify particular people/ characters through recurring motifs,

actions, plot points, setting and characteristics. These questions included, “what is an archetype?”,

“What comes to mind when you think of a superhero?” And “what do Batman, Spiderman and

Superman all have in common?” This use of questioning was recording through photographic

evidence where Student 1 came up with the following answers: “It’s a type of arch”. “Superman”,

and “ they are superheros” (Refer to Appendix G). Case study student 1’s responses showed limited

justification and were predictable. Thus, I devised a traffic cone system (Refer to Appendix E & G) to

collect student data and feedback. I asked the students to write on a sticky not one thing they

understood from the lesson and one thing they needed to work on, and to place it on the traffic cone

system where it suited their learning best. Case student 1 placed their exit slip in the green cone;

indicating that he understood the concept and wrote “I understood archetypes (Refer to Appendix G).

Modelled to the class during the next phase of the unit, I scaffolded the qualities and characteristics

of traditional archetypes and gave examples of varying characters who suited the description of each

archetypal character. Students were then asked to independently complete the modelled task using

the worksheet displayed to the right. I found that by modelling this exercise and giving Case 1 a guide,

they were able to complete the worksheet. However, their ability to write cohesive sentences was

fractured as “children with dysgraphia often struggle to organise their ideas into well-constructed

stories and paragraphs” (Gilen et al, 2006, p. 5). To aid Student 1 with an opportunity to meet the

learning intention based upon the Year 7 Australian Curriculum Achievement Standard: (demonstrate

understanding of archetypal characters using visual and written texts to justify personal viewpoints) I

placed case study 1 and 2 together in pairs during a task to reinforce the oral to written language

connection as “learners articulate to each other how to express an opinion, an argument, or a stance

and provides an immediate authentic audience” (Meter 2011, p.232).

During Phase 2, case study student 1 responded to the text My Hero Academia.to justify how their

chosen character fits an archetype using a banner template (Refer to Appendix G). Student 1 was

determined to pass English as discussed with their classroom teacher, hence they produced a

substantial piece of work which met the criteria to a satisfactory level. I found that as cited on the

marked rubric that student 1 began to justify why their chosen character fits an archetype using

supporting evidence of events from the text and had understood the plotline of their chosen text. But

they had not explicitly stated the characteristics of their character to justify why those particular

series of events fit the hero archetype. These points demonstrate a beginning level of inferencing but

are not explicitly stated. Consequently, not all sentences were cohesive and punctuated correctly

which lowered their potential grade which was a C- (Refer to Appendix G). Student 1 would benefit

self checking their own writing. Sheena Cameron (2013) states that within the independent writing

phase of the Gradual Release Model, students should read their own work to ensure it makes sense

and to search or errors which helps them to make “re-crafting decisions as they progress as writers”

(Cameron 2013, p.54). Hence during student 1’s next phase of learning of fairy tales I explicitly

modelled this idea on the interactive whiteboard of a narrative I created and got students to

independently edit their own twisted fairy tale that they produced as a short formative assessment

task to ensure that during Phase 3 this was something that was emphasised and welcomed during the

summative task.

During Phase 3 of case study student 1’s Shrek analysis students were guided through the task using a

rubric where I placed high expectations upon the students to meet the criteria of ‘At (2)’ (Refer to

Appendix G) and encouraged students to take notes for those students wanted to receive a higher

grade. Students were to answer a serious of questions that required them to use evidence from the

text and prior knowledge from previous topics engaged in to justify their answer; as well as create a

table comparing the modern archetypal characters within Shrek with their traditional archetype.

8 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Through the use of the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model I was able to scaffold student 1’s

developing skills and knowledge through questioning, prompting, and cuing” (Fisher & Frey 2013,

p.39) which was embedded continuously through formative assessment strategies which will be

discussed later on. As demonstrated through the assessed rubric (Refer to Appendix G) I found…

‘Student 1 demonstrated a satisfactory understanding of the movie Shrek. A majority of their answers

used supporting evidence for implied meaning. However, their ability to elaborate upon their answers

were basic. Questions 4 and 12 were very strong as they had used examples outside of the text to

support and justify their answers (Refer to Appendix G). However, there were grammatical and

punctual mistakes which lead to sentence in cohesion. Student 1 had the option to write up their

analysis using a laptop which limited the amount of errors which were consistent within their banner

in Phase 2. Moreover, the Gradual Release of Responsibility Model allowed student 1 the opportunity

during independent work to…

▪ Understand the purpose for writing.

▪ Identify and follow a criterion.

▪ Organise ideas into paragraphs which justify personal viewpoints through evidence of the text

they are responding to.

▪ Apply prior knowledge outside of the text to support their answer.

Through a writing survey I conducted, case study student 1 wrote that throughout the unit on

Fantastic Worlds it “deepened their understanding so they can focus on characters and get to know

them better”. In their thank you letter to me also they wrote “I feel having you in the class has

improved my ability to do English tasks”(Case study student 1- Refer to Appendix G)

Findings: 4.1- Case 2

Through a scaffolded approach using the Gradual Release of Responsibility model of instruction, I

guided case study student 2 with a guided approach towards developing an understanding of how to

respond to literary texts through appropriate and justifiable responses through reading and viewing a

multitude of texts.

The findings revealed that a learning environment was established in which students engaged in rich

conversations, in sort to create justifiable responses that demonstrated conceptual knowledge of

varying texts. Designed as a delineated pedagogy, during Phase 1 I used Fisher & Frey’s (2008) Focus

Lesson strategy. This component allows the teacher to “model his or her thinking and understanding

of the content for students. Usually brief, focus lessons establish the purpose or intended learning

outcome and clue students into the standards they are learning” (Fisher 2008, p.1). In addition, this

teacher instructed model, provided me with the opportunity to build and/or activate background and

prior knowledge. Hence, by using the method of ‘hover and chin it’, it allowed me to collect student

data through photographical evidence to examine how quickly student 2 picked up the conceptual

ideas of a what an archetype is and how well they could relate this new found knowledge in relation

to other texts. Using the Australian Curriculum, students were covering the sub-strand: Responding to

Literature (ACELT1620), and students learning intentions were: Understand what an archetype is and

identify different archetypal characters through various texts. And, justify personal viewpoints to

explain the characteristics of archetypal characters. Case study student 1 responded to the question

demonstrated on the PowerPoint:

What is an archetype? - “a type of made up character”.

When I say superhero, what comes to mind? – “someone who save the day. Someone who is selfless,

like superman”.

What do Batman, Superman and Spiderman all have in common? – “They are all heroes”.

9 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Case student 2’s responses above demonstrate a sound knowledge of attempting to associate an

archetype with fictional characters through which is demonstrated in question two where student 2

has started to give justification of answers by listing the characteristic of ‘selflessness’ and associating

this word with helping people. To challenge not only student 2’s thinking but the rest of the class,

students were called upon by myself using a deck of cards with their name on one card where

students would have the opportunity to share their answer. When student 2 was called upon during

this session I asked whether they would like to share their answer, however they shock their head. As

discussion was a vast contribution to my pedagogical practices, I wanted student 2 to feel

comfortable to share their findings with their peers. Thus, in order to establish a positive culture for

writing, Sheena Cameron (2013) states the importance of teachers praising risk taking and problem

solving. This strategy was conducted throughout following sessions where students further conducted

in opportunities to “think, pair and share”(Cameron 2013, p.40) to develop justifiable responses to

texts using archetypal characteristics and evidence.

In preparation of Phase 2, I placed case study 1 and 2 together as mentioned above case study 1

lacked the knowledge to justify their answer; whereas case 2 had greater knowledge to use evidence

to support their answer. This was firstly modelled on the board. This was demonstrated as shared/

collaborative learning which proved to consolidate case study students 1 and 2’s understanding with

the content to problem solve, discuss, negotiate and think with one another. Both students were able

to justify their personal viewpoints and critically engage in conversation and “reflect on other

viewpoints” (ACARA 2016) which ensured individual accountability.

During Phase 2, case study student 2 responded to the text Harry Potter to justify how their chosen

character fits an archetype. Student 2 was to construct an archetype banner independently. I found

that through modelled, shared and guided scaffolding, case student 2 could succinctly compose ideas

through reflecting on the criteria from previous lessons; using the rubric (Refer to Appendix H) to

ensure that their responses showed the ability to support evidence for implied meaning in three or

more examples cited in responses. I found that as cited on the marked rubric, ‘they have

demonstrated a strong understanding of what an archetype is and used supporting evidence from the

text to justify their reasoning’. ‘There is a good use of adjectives to support their chosen characteristics

of their archetypal character’. Although student 2 has demonstrated fantastic inferred meaning from

their chosen text, their ability to provide justification using typical archetype traits of a hero, it is

limited in paragraph four (Refer to Appendix H). Student 2 would gain from drafting their work and

gaining feedback from the teacher prior to engaging in their good copy, reiterating how to develop a

good PEEL/ TEEL paragraph, “reviewing the learning and sharing successes to make improvements in

their writing” (Cameron 2013, p.52).

Before commencing in Phase 3, The Gradual Release cycle was used again in using various forms of

assessment to gage student knowledge which will be discussion later. Student’s engaged in various

learning activities around the genres within Fantastic Worlds: Traditional fairy tales, twisted fairy tales

and modern fantasy in preparation for their final summative assessment and work on student 2’s

misconceptions about writing.

During Phase 3, students were introduced to the movie analysis task guided through the use of a

rubric where I placed high expectations upon the students to meet the criteria of ‘At (2)’ (Refer to

Appendix G & H) and encouraged students to take notes for those students wanting to receive a

higher grade; in particular, case student 2. Students were to answer a series of questions that

required them to use evidence from the text and prior knowledge from previous topics to justify their

answer; as well as create a table comparing the modern archetypal characters within Shrek with their

traditional archetype. As I facilitated and modelled the discussion, student 2 evidently scribed notes in

10 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

their book to extend their learning, and whilst watching the movie Shrek they also partook in note

taking extensively to better their final grade. Through the process of marking case study student 2’s

work they have demonstrated great knowledge of the movie and used implied meaning of the text

with supporting evidence. Their prior knowledge of archetypes is evident throughout more than 80% of

their answers (Refer to Appendix H for marked assessment). In comparison to case study 2’s

justification during Phase 1 and 2, they have clearly decoded both written and visual texts to justify

their answers within their writing. For example,…

Is Shrek based on a Traditional Fairy Tale, Twisted Fairy Tale or Modern Fantasy? And justify your

point.

“I think Shrek is based on Modern Fantasy because it includes Fairy Tale features and characters, but it

has a modern twist and modern aspects. For example, there were characters portrayed as princesses

and other royal characters, but they weren’t traditional, they had character flaws and were twisted to

fit the story-line” (Case study student 2).

In all, case study student 2 has demonstrated extensive ability to use supporting evidence for implied

meaning using a multitude of examples within their answers as a response to texts. This was evident

in a student writing survey as well were student 2 wrote: “It helps me read and watch movies because

now I can now identify archetypes”. “It helps me write because I write more in-depth”. And “I think

learning about types of narratives has improved my writing skills because you really explained it in a

good and realistic/ fun way” (case study student 2- Refer to Appendix H)

Discussion

During the modelled construction phase, this is simply not just showing, but is accompanied by

“spoken language designed to provide a narrative for the learner to follow” ( Fisher & Frey 2013,

p.28). Fisher & Frey (2013) state that when students possess a skill or strategy that is modelled for

them rather than stated, they will gain a vaster understanding for “when to apply it, what to watch

out for, and how to analyse their success” (Fisher & Frey 2013, p.28). Hence, introducing the

formative assessment strategy of ‘Hover and Chin It’ which was first introduced by Hansberry

Educational Consultant Australia had to be modelled firstly in order for students to appropriately use

this strategy. This is consistent with four dimensions of learning: “declarative ( What is it? ),

procedural ( How do I use it? ), conditional ( When and where do I use it? ), and reflective ( How do I

know I used it correctly? )” (Angelo, 1991 cited in Fisher & Frey 2013, p.28). The use of individual

whiteboards provided case study students 1 and 2 to challenge their metacognitive thinking in

responding to visual or written texts as a quick formative assessment of student learning. For

example, in preparation for their summative assessment students watch a clip from Narnia and had to

justify their responses to the following questions…

▪ Are modern fantasy texts similar the twisted fairy tales? Agree or disagree and justify your

answer.

▪ How would you describe Lucy in Narnia, and which archetype would you give her based on

the clip we just watched?

▪ Knowing Lucy’s story now, what archetype would you place her under now and why?

Upon drawing random names from a deck of class cards, case students 1 and 2 demonstrated a

growing knowledge of the criteria and learning objectives introduced during “focused instruction”

(Fisher & Frey 2013, p.18). Hence the continuous use of questioning through the unit allowed for

repetition and practice of new and learnt skills/ strategies that “checked for understanding during

11 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

guided instruction, and uncovered errors and misconceptions which were essential to student

growth”. (Frey & Fisher2013, p.41).

I initially used the traffic cone system as stated previously as formative assessment where students

placed their response to a question in either the red, yellow or green bag. However, after recording

student’s responses and colour coding them to identify their abilities, 95% of the class placed their

slip in the green section during both accounts with little to now justification. This was particularly

interesting and insightful to see how the decisions of others informed individual decisions within the

class; case 1 particularly who placed their response in the green section stating, “I understand”. This

made me reconsider my pedagogical practices and strategies and question, how can I record student

knowledge using a more structured approach? Hence why I tried exit slips. Exit slips can “document

learning, emphasize the process of learning, and evaluate the effectiveness of instruction” (Bafile,

2004 & Fisher & Frey, 2004 cited in Leigh 2012, p.191). Exit slips are ideal for capturing individual

spurts of thinking; just when students think they cannot be heard or have nothing to share, “exit slip

writing can capture their ideas as they occur” (Leigh 2012, p.191). Moreover, through constructing

premade exit slips (Refer to Appendix E) they lead to self-reflective thought which in turn

strengthened case study 1 & 2’s interpersonal communication skills which was reflected within their

two summative assessment pieces which justified their findings to meet the learning intentions and

criterion explicitly stated which can be found in Appendix G and H.

Conclusion

Integrating the use of the Gradual Release of Responsibility Framework by Pearson and Gallagher

(1983), allowed me to scaffold student’s development of skills and knowledge through questioning,

prompting, and cuing through reading and viewing texts. Which lead to case 1 and 2 responding

appropriately through the use of justification within their writing. Case study student 1; a Year 7

student who is diagnosed with Dysgraphia and Case student 2; a high achieving Year 6 student could

reflect on ideas and opinions about characters, settings and events in literary texts and identify and

justify personal points of view through verbal and written form (ACARA 2016). I believe this was

through the use of modelled, guided and collaborative learning opportunities which allowed student

1 to benefit from more knowledgeable others and consistently be challenged through formative

assessment strategies: formative assessments - a written exit pass, ‘hover and chin it’ on whiteboards

to practice written justification in response to a multitude of texts to better their ability to analyse

texts and respond within their summative assessment pieces. Both students could evidently construct

a cohesive paragraph which answered the question using not only evidence from the text but prior

knowledge. Moreover, this action research has empowered me to reflect critically in order to examine

my methods and pedagogical practices to enhance individual student learning and plan for inclusivity

and to help evaluate and assess learning to aid the ‘where to’ now process. I would be inclined to

teach this unit of writing on Fantastic Worlds again using the guidance of the Gradual Release

Framework and formative assessment strategies such as the use of exit slips and hover and chin it to

assess student learning. However, to better student outcomes I would engage in the practice of

ensure students appropriately understand how to construct proper paragraphs at the beginning of

the year and work on student grammar and punctuation within Spelling. This would ensure that

these areas do not degrade their final outcome as this was a minor flaw within both cases final

summative assessment.

12 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Reference list

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) 2016, The Australian Curriculum

v8.3, viewed 1 October 2019, http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (aitsl) 2017, Australian Institute for Teaching

and School Leadership, viewed 1 October 2019, https://www.aitsl.edu.au

Cameron, S 2013, The Writing Book: A Practical Guide for Teachers, S&L Publishing Ltd, Auckland NZ

Ewing, R, Le Cornu, R & Groundwater-Smith, S 2014, Teaching Challenges and Dilemmas, Cengage

Learning Australia, Australia

Fisher, D & Frey, N 2008, Better learning through structured teaching: A framework for the gradual

release of responsibility, Alexandria, VA USA

Fisher, D & Frey, N 2013, Better Learning Through Structured Teaching : A Framework for the Gradual

Release of Responsibility, 2nd Edition, Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development,

Alexandria VA, USA

Fisher, D & Frey, N 2013, Engaging the Adolescent Learner, International Reading Association, viewed

28 September 2019, < https://keystoliteracy.com/wp

content/uploads/2017/08/frey_douglas_and_nancy_frey-

_gradual_release_of_responsibility_intructional_framework.pdf>

Government of Australia 2016, Australian Bureau of Statistics, Government of Australia, viewed 28

September 2019, < https://www.abs.gov.au/ >

Hine, G 2013, ‘The importance of action research in teacher education programs’, Issues in

Educational Research, vol. 23, no. 2, pp. 151-163

Leigh, R 2012, ‘The Classroom is Alive with the Sound of Thinking: The Power of the Exit Slip’,

International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 189-196

McAteer, M 2013, Action Research in Education, SAGE Publications Ltd, London

Menter, I 2011, A Guide to Practitioner Research in Education, SAGE Publications, London

13 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Power, B 2019, ‘The Answer to Better Student Writing? Asking Better Questions’, Scholastic, viewed

27 September 2019, < https://www.scholastic.com/teachers/articles/teaching-content/x201cthe-

answer-better-writing-better-questionsx201d/>

SPELD Foundation 2019, What is Dysgraphia?, DSF, viewed 29 September 2019,

<https://dsf.net.au/what-is-dysgraphia/>

William, W 1987, Questions, Questioning Techniques, and Effective Teaching, Nationai Education

Association, Washington, D.C

14 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendices

Appendix A: Map of the school/preschool (highlighting relevant structures/resources)

15 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix B: Photographs of the classroom/preschool environment

There are 26 classroom spaces in both solid construction and transportables. There is an administration block, school hall, canteen and a

multi-purpose area, which includes an art room and a fully integrated ICT suite and Resource Centre. BER funding was used to build a

GLA (general learning area) consisting of 8 classroom spaces and a learning corridor. A COLA (covered outdoor learning area) has

recently been built with site funds and is used for multiple purposes including school assemblies.

I have been placed in a composite Year 6/7 class (Room 23) which consists of 29 students; 13 of which are girls and 16 boys. There is 1

EALD student, who is taken out of the classroom once a week on a Monday by the class SSO, and 1 student who has been diagnosed

with Dysgraphia which is a processing disorder. The students participate and heavily focus on both Mathematics and Reading which is a

vast focus within the whole school based on student PAT Testing. Room 22 and 23 work together to team teach in both Maths and

Writing. Students participate in in NIT/ Extra Curricula Lessons such as Civics, Performing Arts, P.E, and LOTE (Japanese). The classroom

consists of flexible seating; using exercise balls and crates to gain MIP and attention to learning. Students have access to a study area

outside of the classroom in the hall which consists of desktop computers and class laptops for research and inquiry -based learning. As

well as a whiteboard and interactive board utilised in a majority of learning tasks. Students are grouped in table groups to maximise

individual participation using group work during learning tasks positioned to prevent tripping hazards and clear pathways to both exits.

16 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix C: Analysis of learning for case 1 & 2

Case 1 – Analysis of information report to develop an understanding of students’ strengths and

weaknesses in writing (ASSESSMENT CONDUCTED BY SUPERVISING TEACHER)

17 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix C: Analysis of learning for case 1 & 2

Case 2– Analysis of biography and narrative to develop an understanding of students’ strengths and

weaknesses in writing (ASSESSMENT CONDUCTED BY SUPERVISING TEACHER)

18 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix D: Anticipatory planning web (mind map/brainstorm) for case 1 & 2

Case 1

Case 2

19 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix E: Data collection method templates – Traffic cone system (Formative Assessment):

20 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix E: Data collection method templates – Self Reflection Data Template

21 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix E: Data collection method templates – Student Feedback Template

22 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

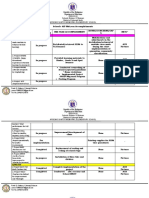

Week: 1 2 3 4 5

Work Samples > archetype/ archetypal > Collect student textual

character definition analysis of Shrek Movie

worksheet (Monday) (Friday).

>Mini summative

assessment- pennant flag.

Student Feedback > traffic cone student self- > traffic cone student self- > Exit slip on Traditional Fairy > Exit slip on Twisted Fairy > Student writing survey

evaluation at the end of evaluation at the end of tales tales

the lesson (Monday + the lesson (Friday).

Friday).

Annotated Images > Take pictures of students > Take pictures of students

questioning answers questioning answers during

(Work samples- hover

during facilitated facilitated discussion

& chin it) discussion- hover & chin it (Monday)

(Monday)

Supervisor Feedback > Feedback on Monday/ > Feedback on Monday > Feedback on Monday

Tuesday lessons. (Observation of Twisted

Fairy tale lesson).

Reflective Journal > Analyse of observations > Analyse of observations > Analyse of observations + > Analyse of observations + > Analyse of observations +

+ student discussion points + student discussion points student discussion points & student discussion points & student discussion points &

& student self feedback. & student self feedback. student self feedback. student self feedback. student self feedback.

23 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence (students/child’s feedback x 3

24 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence (students/child’s feedback x 3

25 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence work sample 1- Hover and Chin It Photographs from lesson 1

What is an archetype?

When I say superhero, what comes to mind?

What do Batman, Superman and Spiderman all have in common? –

26 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence work sample 2

27 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence work sample 2 (Marked Rubric)

28 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence work sample 3 (Shrek Analysis)

29 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence work sample 3 (Shrek Analysis)

30 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence work sample 3 (Shrek Analysis)

31 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence work sample 3 (Shrek Analysis)

32 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence work sample 3 (Shrek Analysis- Marked Rubric)

33 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence work sample 3 (Shrek Analysis- Marked Rubric)

34 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 evidence feedback from Supervising Sample 1

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence (students/child’s feedback x 3, work samples x3, feedback from

Supervising Teacher x 3, planning x 3, evaluation of planning x 3,

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence (students/child’s feedback x 3, work samples x3, feedback from

Supervising Teacher x 3, planning x 3, evaluation of planning x 3,

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence (students/child’s feedback x 3, work samples x3, feedback from

Supervising Teacher x 3, planning x 3, evaluation of planning x 3,

Appendix G: Case 1 evidence (students/child’s feedback x 3, work samples x3, feedback from

Supervising Teacher x 3, planning x 3, evaluation of planning x 3,

35 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 evidence feedback from Supervising Sample 2

36 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 evidence feedback from Supervising Sample 3

37 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

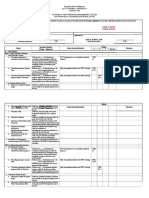

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 lesson plan 1 (Phase 1)

38 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 lesson plan 1 (Phase 1)

39 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 lesson plan 2 (Phase 2)

40 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 lesson plan 2 (Phase 2)

41 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 lesson plan 2 (Phase 3- introduction to modern fantasy in preparation

from their Shrek Analysis)

42 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 lesson plan 2 (Phase 3- introduction to modern fantasy in preparation

from their Shrek Analysis)

43 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 lesson plan 2 (Phase 3- introduction to modern fantasy in preparation

from their Shrek Analysis)

44 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 evaluation of planning Phase 1

45 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 evaluation of planning Phase 1

46 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix G & H: Case 1 & 2 evaluation of planning Phase 1

47 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix H: Case 2 evidence students/child’s feedback

48 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix H: Case 2 evidence students/child’s feedback x 3,

49 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix H: Case 2 evidence work samples x3,

What is an archetype?

What comes to mind when I say Superhero?

What does Batman Spiderman and Superman all have in common?

50 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix H: Case 2 evidence, work samples x3,(Summative Assessment)

51 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix H: Case 2 evidence, work samples x3,(Summative Assessment- Marked Rubric)

52 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

53 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix H: Case 2 evidence work samples x3 (Shrek Analysis

54 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix H: Case 2 evidence work samples x3, (Shrek Analysis

55 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix H: Case 2 evidence work samples x3, (Shrek Analysis)

56 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix H: Case 2 evidence work samples x3, (Shrek Analysis- Marked Rubric)

57 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

Appendix H: Case 2 evidence work samples x3, (Shrek Analysis- Marked Rubric)

58 Word Count: 5013 (less references, quotes and appendix’s)

You might also like

- Rationale Learning SequenceDocument15 pagesRationale Learning Sequenceapi-221544422No ratings yet

- Australian Professional Standards For TeachersDocument5 pagesAustralian Professional Standards For Teachersapi-320822132No ratings yet

- Essay Edfd Assessment FinalDocument6 pagesEssay Edfd Assessment Finalapi-357445221No ratings yet

- Edfd260 Assignment 2Document9 pagesEdfd260 Assignment 2api-252779423No ratings yet

- Inquiry Proposal 2Document10 pagesInquiry Proposal 2api-519322453No ratings yet

- Student Engagement Self-Regulation Satisfaction and Success inDocument220 pagesStudent Engagement Self-Regulation Satisfaction and Success inXaiNo ratings yet

- Primary Final Report - 2019-1 Ellie 1Document6 pagesPrimary Final Report - 2019-1 Ellie 1api-478483134No ratings yet

- PLP At1Document23 pagesPLP At1api-511483529No ratings yet

- 4 3 1 Manage Challenging BehaviourDocument6 pages4 3 1 Manage Challenging Behaviourapi-322000186No ratings yet

- Educ9406 Liz Ray Assignment 1 Tiered LessonDocument7 pagesEduc9406 Liz Ray Assignment 1 Tiered Lessonapi-296792098No ratings yet

- Professional Inquiry Project ReportDocument18 pagesProfessional Inquiry Project Reportapi-426442865No ratings yet

- Teaching Philosophy EdfdDocument11 pagesTeaching Philosophy Edfdapi-358510585No ratings yet

- Pip Proposal RevisedDocument7 pagesPip Proposal Revisedapi-361317910No ratings yet

- Rational Number Open Task RubricDocument1 pageRational Number Open Task Rubricapi-284319044No ratings yet

- Assignment Cover Sheet: TH THDocument8 pagesAssignment Cover Sheet: TH THapi-265334535100% (2)

- Edfd452 Evidence - Edss341 A3Document21 pagesEdfd452 Evidence - Edss341 A3api-358837015No ratings yet

- Edma310 Unit PlannerDocument17 pagesEdma310 Unit Plannerapi-316890023No ratings yet

- Maths Interview and Open TaskDocument4 pagesMaths Interview and Open Taskapi-317496733100% (1)

- CTL Assignment-1-18035432 1Document60 pagesCTL Assignment-1-18035432 1api-518571213No ratings yet

- Science: Lesson Plans OverviewDocument22 pagesScience: Lesson Plans Overviewapi-372230733No ratings yet

- Nahida Fahel-Inclusive Education Assessment 2Document12 pagesNahida Fahel-Inclusive Education Assessment 2api-464662836No ratings yet

- Edfd452 At2 Critical Reflections Elsie StoelDocument6 pagesEdfd452 At2 Critical Reflections Elsie Stoelapi-319869838No ratings yet

- Maths Good Copy 2 WeeblyDocument11 pagesMaths Good Copy 2 Weeblyapi-316782488No ratings yet

- Week 7 Edma262Document2 pagesWeek 7 Edma262api-400302817No ratings yet

- Lesson Plan - Mathematics Edma2622015 1Document4 pagesLesson Plan - Mathematics Edma2622015 1api-235505936No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 AutosavedDocument12 pagesAssignment 2 Autosavedapi-435781463No ratings yet

- Academic Essay. Written Reflections & Critical AnalysisDocument4 pagesAcademic Essay. Written Reflections & Critical AnalysisEbony McGowanNo ratings yet

- Emily Henderson Edma310 Assessment Task 2 UnitplannerDocument8 pagesEmily Henderson Edma310 Assessment Task 2 Unitplannerapi-319586327No ratings yet

- Implementing The Australian Curriculum:: Explicit Teaching and Engaged Learning of Subjects and CapabilitiesDocument58 pagesImplementing The Australian Curriculum:: Explicit Teaching and Engaged Learning of Subjects and CapabilitiesHafizur Rahman DhruboNo ratings yet

- Assessment Task 2Document2 pagesAssessment Task 2api-357915760No ratings yet

- Edma360 Assessment 3-4 4 1Document17 pagesEdma360 Assessment 3-4 4 1api-265542260No ratings yet

- Edss UnitDocument6 pagesEdss Unitapi-265537480No ratings yet

- Assessment Task 1Document6 pagesAssessment Task 1api-286646193No ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Lesson Plan and CritiqueDocument12 pagesAssignment 1 Lesson Plan and Critiqueapi-327519956No ratings yet

- Gaining Insights From Research For Classroom Numeracy PlanningDocument9 pagesGaining Insights From Research For Classroom Numeracy Planningapi-358204419No ratings yet

- Mathematics Unit PlannerDocument7 pagesMathematics Unit Plannerapi-255184223No ratings yet

- Pip Proposal 2Document7 pagesPip Proposal 2api-361854774No ratings yet

- Assessment 3 PortfolioDocument27 pagesAssessment 3 Portfolioapi-382731862No ratings yet

- Edfd452 Evidence - Edss341 A3Document21 pagesEdfd452 Evidence - Edss341 A3api-358837015No ratings yet

- Edma360 LessonsDocument8 pagesEdma360 Lessonsapi-299037283No ratings yet

- Edma Rubricccc-2Document2 pagesEdma Rubricccc-2api-318830177No ratings yet

- Edfd340 Assignment 2Document9 pagesEdfd340 Assignment 2Nhi HoNo ratings yet

- Assessment Two EdfdDocument8 pagesAssessment Two Edfdapi-265573453No ratings yet

- Amyryan 102097 rtl2 Assessment2Document11 pagesAmyryan 102097 rtl2 Assessment2api-374402085No ratings yet

- AUS LessonPlans Year6 2014 WebVDocument6 pagesAUS LessonPlans Year6 2014 WebVMadalina ChiriloiNo ratings yet

- Inclusive Assignment 2Document12 pagesInclusive Assignment 2api-435738355No ratings yet

- 2018 Maths Reflection FinalDocument7 pages2018 Maths Reflection Finalapi-347389851No ratings yet

- Insights Into Challenges: Assignment 1: Case StudyDocument6 pagesInsights Into Challenges: Assignment 1: Case Studyapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Edst261 Group AssignmentDocument18 pagesEdst261 Group Assignmentapi-512557883No ratings yet

- Final ReflectionDocument2 pagesFinal Reflectionapi-332457208No ratings yet

- Howe Brianna 1102336 Task1 Edu202Document8 pagesHowe Brianna 1102336 Task1 Edu202api-457440156No ratings yet

- Esm310 Scott Tunnicliffe 212199398 Assesment 1Document8 pagesEsm310 Scott Tunnicliffe 212199398 Assesment 1api-294552216No ratings yet

- Barriers Faced by Parents with Disabilities in School CommunitiesDocument6 pagesBarriers Faced by Parents with Disabilities in School CommunitiesQueenNo ratings yet

- WeeblyDocument2 pagesWeeblyapi-517802730No ratings yet

- Luke Ranieri 17698506 Assessment 1 For 102091Document22 pagesLuke Ranieri 17698506 Assessment 1 For 102091api-486580157No ratings yet

- Campbell Chloe 1088079 Edu412 Task1Document8 pagesCampbell Chloe 1088079 Edu412 Task1api-453388446No ratings yet

- Final 5e Lesson Plan - Grocery StoreDocument4 pagesFinal 5e Lesson Plan - Grocery Storeapi-548497656No ratings yet

- Pattern Lesson PlanDocument6 pagesPattern Lesson Planapi-283147275No ratings yet

- Maths Unit Planner - Standard 2Document20 pagesMaths Unit Planner - Standard 2api-263598116No ratings yet

- Lean Six Sigma - WikipediaDocument4 pagesLean Six Sigma - Wikipediakirthi83No ratings yet

- 34TH Nrm/a Victory Day AnniversaryDocument4 pages34TH Nrm/a Victory Day AnniversaryGCICNo ratings yet

- TK/PPD: Theory of Knowledge Presentation Planning DocumentDocument3 pagesTK/PPD: Theory of Knowledge Presentation Planning Documentnandini kuchhalNo ratings yet

- Delhi Urban Art Commission ReviewDocument11 pagesDelhi Urban Art Commission ReviewSmritika BaldawaNo ratings yet

- Ecotourism in Jharhkand Change Impact AnDocument5 pagesEcotourism in Jharhkand Change Impact AnthaimuNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18 CVR & FDRDocument41 pagesChapter 18 CVR & FDRveenadivyakishNo ratings yet

- Working at Stabbing Board During CasingDocument2 pagesWorking at Stabbing Board During CasingkhurramNo ratings yet

- Arsenio Santos Memorial Elementary SchoolDocument5 pagesArsenio Santos Memorial Elementary SchoolCel Rellores SalazarNo ratings yet

- SLIDES 3 MarketingDocument18 pagesSLIDES 3 MarketingBibi Shafiqah Akbar ShahNo ratings yet

- Name of Ratee Department Name: Leyte Normal UniversityDocument5 pagesName of Ratee Department Name: Leyte Normal UniversityAnonymous PcPkRpAKD5No ratings yet

- Conversation Questions GenerationDocument3 pagesConversation Questions GenerationRania KuraaNo ratings yet

- MRP To Mrp2 and Erp To Erp2Document157 pagesMRP To Mrp2 and Erp To Erp2MD ABUL KHAYERNo ratings yet

- Constructing Test Questions: Table of SpecificationsDocument54 pagesConstructing Test Questions: Table of SpecificationsRetchel Tumlos MelicioNo ratings yet

- Meitheal Closure FormDocument4 pagesMeitheal Closure FormtqsnrNo ratings yet

- Background Knowledge of TBLTDocument3 pagesBackground Knowledge of TBLTyessodaNo ratings yet

- Robert Kraft - Sample Allegation StoryDocument3 pagesRobert Kraft - Sample Allegation Storyapi-457917734No ratings yet

- ECCE Speaking Commentary PDFDocument2 pagesECCE Speaking Commentary PDFXara KarraNo ratings yet

- Bio DataDocument4 pagesBio DatakamalgkNo ratings yet

- Case Study: Walmart Inc. Takes On: Subject: Retail Management StategyDocument8 pagesCase Study: Walmart Inc. Takes On: Subject: Retail Management StategyAkhil ChaudharyNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Holds Bus Company Liable for Passenger DeathDocument2 pagesSupreme Court Holds Bus Company Liable for Passenger DeathNasheya InereNo ratings yet

- A Study On Out Bound Logistics in Sankar Sealing Systems: Under Guidance of Dr.K. RavishankarDocument10 pagesA Study On Out Bound Logistics in Sankar Sealing Systems: Under Guidance of Dr.K. Ravishankarலோகேஸ்வரன் துரைசாமி100% (1)

- The Schematic Structure of Computer Science Research ArticlesDocument11 pagesThe Schematic Structure of Computer Science Research ArticlesAlfin KarimahNo ratings yet

- UK Student Visa Application for English StudyDocument13 pagesUK Student Visa Application for English StudyManuel Magaña Bribiesca0% (2)

- Curriculum Vitae: From: Shikhar VermaDocument1 pageCurriculum Vitae: From: Shikhar Vermaशिखर वर्माNo ratings yet

- German Short Stories: 9 Simple and Captivating Stories For Effective German Learning For BeginnersDocument51 pagesGerman Short Stories: 9 Simple and Captivating Stories For Effective German Learning For BeginnersRamsai ChigurupatiNo ratings yet

- Job AnalysisDocument27 pagesJob AnalysisNiaz AhmedNo ratings yet

- Multiple Choice Scoring Methods - Which is Best for Higher Ed AssessmentDocument16 pagesMultiple Choice Scoring Methods - Which is Best for Higher Ed AssessmentPremier BrandsNo ratings yet

- PE7 Running Skills Lesson PlanDocument2 pagesPE7 Running Skills Lesson PlanMetchie Palis89% (9)

- Predictors of Board Exam Performance of The Dhvtsu College of Education GraduatesDocument4 pagesPredictors of Board Exam Performance of The Dhvtsu College of Education GraduatesKristine CaceresNo ratings yet

- Depreciation Chart 11-12 (FY)Document4 pagesDepreciation Chart 11-12 (FY)specky123100% (1)

- Writing Screenplays That Sell: The Complete Guide to Turning Story Concepts into Movie and Television DealsFrom EverandWriting Screenplays That Sell: The Complete Guide to Turning Story Concepts into Movie and Television DealsNo ratings yet

- Surrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) (The Surrounded by Idiots Series) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisFrom EverandSurrounded by Idiots: The Four Types of Human Behavior and How to Effectively Communicate with Each in Business (and in Life) (The Surrounded by Idiots Series) by Thomas Erikson: Key Takeaways, Summary & AnalysisRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (2)

- Summary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisFrom EverandSummary: How to Know a Person: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen By David Brooks: Key Takeaways, Summary and AnalysisRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Stonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonFrom EverandStonewalled: My Fight for Truth Against the Forces of Obstruction, Intimidation, and Harassment in Obama's WashingtonRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (21)

- Learn Spanish with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Spanish Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn Spanish with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Spanish Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (136)

- 1000 Words: A Guide to Staying Creative, Focused, and Productive All-Year RoundFrom Everand1000 Words: A Guide to Staying Creative, Focused, and Productive All-Year RoundRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (13)

- Wordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageFrom EverandWordslut: A Feminist Guide to Taking Back the English LanguageRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (427)

- How Not to Write a Novel: 200 Classic Mistakes and How to Avoid Them—A Misstep-by-Misstep GuideFrom EverandHow Not to Write a Novel: 200 Classic Mistakes and How to Avoid Them—A Misstep-by-Misstep GuideNo ratings yet

- Body Language: Decode Human Behaviour and How to Analyze People with Persuasion Skills, NLP, Active Listening, Manipulation, and Mind Control Techniques to Read People Like a Book.From EverandBody Language: Decode Human Behaviour and How to Analyze People with Persuasion Skills, NLP, Active Listening, Manipulation, and Mind Control Techniques to Read People Like a Book.Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- Writing to Learn: How to Write - and Think - Clearly About Any Subject at AllFrom EverandWriting to Learn: How to Write - and Think - Clearly About Any Subject at AllRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (83)

- Learn French with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: French Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn French with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: French Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (81)

- Learn Mandarin Chinese with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Mandarin Chinese Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn Mandarin Chinese with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: Mandarin Chinese Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (15)

- The History of English: The Biography of a LanguageFrom EverandThe History of English: The Biography of a LanguageRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Idioms in the Bible Explained and a Key to the Original GospelsFrom EverandIdioms in the Bible Explained and a Key to the Original GospelsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- How to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent ReadingFrom EverandHow to Read a Book: The Classic Guide to Intelligent ReadingRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (26)

- Everything You'll Ever Need: You Can Find Within YourselfFrom EverandEverything You'll Ever Need: You Can Find Within YourselfRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (41)

- The Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates LanguageFrom EverandThe Language Instinct: How the Mind Creates LanguageRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (916)

- Spanish Short Stories: Immerse Yourself in Language and Culture through Short and Easy-to-Understand TalesFrom EverandSpanish Short Stories: Immerse Yourself in Language and Culture through Short and Easy-to-Understand TalesRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- On Speaking Well: How to Give a Speech with Style, Substance, and ClarityFrom EverandOn Speaking Well: How to Give a Speech with Style, Substance, and ClarityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (15)

- Learn German with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: German Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachFrom EverandLearn German with Paul Noble for Beginners – Complete Course: German Made Easy with Your 1 million-best-selling Personal Language CoachRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (151)