Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Traditional Architecture in Tibet - Linking Issues of Environmental and Cultural Sustainability

Uploaded by

Abreham Fantu Welde AlmazOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Traditional Architecture in Tibet - Linking Issues of Environmental and Cultural Sustainability

Uploaded by

Abreham Fantu Welde AlmazCopyright:

Available Formats

Sign In |

HELP View Cart SEARCH

ADVANCED Help

This website uses cookies to provide you with a variety of services and to improve the usability of our website. By using the website, you agree to the use of cookies in accordance with

Close

our Privacy Policy. BROWSE RESOURCES Search ADVANCED SEARCH

BROWSE RESOURCES Search

FIGURES & DOWNLOAD PDF SAVE TO MY LIBRARY

ARTICLE SECTIONS CITED BY

TABLES

Home > Journals > Mountain Research and Development > Volume 25 > Issue 1 > Article

Select Language ▼

Translator Disclaimer

1 February 2005

Traditional Architecture in Tibet: Linking JOURNAL ARTICLE

5 PAGES

Issues of Environmental and Cultural

Sustainability

William Semple DOWNLOAD PDF

Author A liations +

Mountain Research and Development, 25(1):15-19 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1659/0276- SAVE TO MY LIBRARY

4741(2005)025[0015:TAIT]2.0.CO;2

SHARE GET CITATION

Abstract

is paper examines the changing conditions, including accelerating environmental degradation and the

in uence of modernism, and the impact that these are having on Tibetan architecture and the Tibetan < Previous Article | Next Article >

building tradition. Examples of architectural design and resource management projects throughout the

region are used to explore how the cultural signi cance of building traditions and environmental resource

management can provide a methodology to promote preservation of traditional architecture and the natural

environment. e issues examined and solutions explored could easily apply to other rapidly changing

mountain regions of the world where the deterioration of natural resources calls for a richer understanding

of the connection between environmental and cultural sustainability. e growth of ecotourism as an

industry in many mountain regions gives greater weight to the issues discussed.

Builders and buildings: the Tibetan tradition

Traditional architecture, with its symbolic value and rich artistic embellishments, is one of the measures of

the quality of the craftsmanship that exists within a society. For Tibetans, this is demonstrated in the high

quality woodwork found in their buildings. eir architecture portrays many aspects of Tibetan society and

the variety of in uences that have a ected the culture over the centuries, particularly those of Buddhism. ARTICLE SOURCE

Mountain Research

Tibetan architecture also re ects the important blend of practicality and symbolism that exists in Tibetan and Development

society. While the Buddhist scriptures provide guidelines for temple design and layout (including Vol. 25 • No. 1

proportioning of structures), in resolving the span and proportions of a temple and other building elements, February 2005

the master carpenter will often base his nal decision on the quantity and size of the local materials

available, allowing the practical reality to overrule the strict interpretation of the Buddhist texts.

Intermixed with this is the training of Tibetan carpenters, based on an oral tradition passed on from father to

son and carpenter to apprentice. is is the tradition's strength and its weakness, providing the trade with

social status while making it vulnerable to the impacts of dramatic outside in uences. is was highlighted

during the cultural revolution, when the destruction of temples and monasteries was accompanied by an

attack on all cultural traditions, including that of the builders. Subscribe to BioOne Complete

e stocking of wood timbers for a Tibetan building re ects another aspect of tradition and the collective

Receive erratum alerts for this article

importance of resources. Typically, whether for a monastery or a dwelling, the owner is responsible for

collecting all the construction materials needed for a project (Figure 1). When the materials are gathered,

the building is often constructed with a great deal of donated labor (Figure 2). Receive alerts when this article is cited

Woodwork plays an equally important symbolic role, demonstrated in the carved detailing found

throughout traditional Tibetan buildings. Elaborate woodwork is executed on door and window frames,

paneled doors for window openings, and the exposed parts of buildings such as awnings, rafters, and

beams. In addition, both columns and capitals receive a high level of carved and painted detailing which, in

architectural terms, gives them a special status in Buddhist iconography (Figure 3).

Tradition versus style

For Tibetan communities, preserving traditional architecture can thus mean not only ensuring sociocultural

continuity but also making sure local livelihoods are maintained, based on more sustainable natural

resource use. As part of an international team working under the auspices of the United Nations

Development Programme on the development of an Ecotourism Plan for the Qomolangma Nature Preserve

(QNP) in the Tibetan Autonomous Region of China (TAR), I was asked to design several buildings and

develop design guidelines; I also assisted communities in establishing reforestation projects and helped

them deal with the infrastructure demand from the growing domestic and international tourism industry.

Ecotourism and design guidelines

With its southern border shared with the mountain nation of Nepal, the QNP covers 33,819 km2 and is

among the highest nature preserves in the world. e preserve has a population of 34,000 people, ranging

from nomadic herders of the high plateau to foresters and woodworkers of the valleys along the Tibet/Nepal

border. It includes 4 mountain peaks over 8000 m, among which is Mount Everest (Qomolangma in

Tibetan).

Ecotourism development was established as a goal for this region by the government of the TAR—its

isolation, breathtaking landscape and Tibetan culture being well suited for this industry. While foreign

travelers to the region are willing to spend more money for less infrastructure, where the draw is the

experience of an authentic culture and natural environment, much of the existing situation in the QNP has

not been supporting these values. Government buildings and hotels in the region have increasingly been

constructed in the modernist Chinese style, using imported materials and builders for their construction.

Using the broad ecotourism goals of the project, and drawing upon past experiences in the Himalaya and

my understanding of the economic impact that the construction industry has on local employment, I

developed a set of design guidelines for the QNP which addressed more than just issues of ‘styles’ of

buildings. It included specifying the use of local/traditional materials in construction, the use of local

building methods, and the employment of local builders. e guidelines were a necessary criterion for the

Government to get UNESCO heritage status for QNP.

Designing for tradition

Another task was to design a QNP Training Center (Figure 4), an Administration Building/Guest House, and

prototypes for Guest Houses and Park entrance buildings. In all cases, the designs were developed using

traditional Tibetan architectural principles, including passive solar design features to improve energy

e ciency. Structurally, the spans of the interior timber frame and load bearing capacity of the walls were

designed to be fabricated entirely with local materials.

In addition, the designs re-introduced important traditional Tibetan spatial concepts that have largely

disappeared from the institutional buildings being constructed in the region. us, the QNP Training Center

has a characteristically Tibetan style. Spatially it uses the courtyard and enclosed circumambulatory hallway

to establish movement in the complex. Careful consideration was also given to signi cant regional stylistic

variations in the designs of the other buildings. For example, the entrance building near the Nepal/Tibet

border utilizes a blend of Tibetan and Nepali styles: a Nepali style roof is complemented with Tibetan

detailing, similar to the blending common in the region, particularly in the temples. Stylistic blending is

typical of many areas of the world and of mountain regions, particularly where cultures have existed in

greater isolation and the transition from one culture to another can be read in the decorative details and in

the construction techniques of buildings.

Tourists interviewed during extensive eldwork fully welcomed the return to a more traditional building

form, lamenting the trend towards a building style typically found all over China today. While local Tibetan

o cials and builders have reacted very favorably to the ideas, seeing the QNP as a positive supporter of the

local culture and environment, it is di cult to know what the outcome of these e orts will be in the long

term. A success would support the case that ecotourism has the potential to help revive traditional

architecture and sustainable resource use.

Forestry management and traditional architecture

Ladakh

Ultimately, the future of many traditional architectures depends on the natural resources needed to

construct these buildings. One of the major challenges facing the survival of a building tradition and

traditional architecture is deforestation. One example is Ladakh, a small part of the Tibetan plateau located

in the northeast corner of the Indian State of Kashmir.

Traditionally, the pattern of life in Ladakh revolved around the extremes of its seasons and the tasks carried

out to survive in this environment. Construction of buildings would begin in the early spring, commencing

when, as locals would say, “the waters begin the ow.” In this rugged dry region, these are the meltwaters

from the snow-covered mountains, delivered to the villages in hand-dug channels. is water was necessary

for the fabrication of the mud blocks used in the construction of walls. In less remote areas, as the economy

developed and life became less solely reliant on local materials, people started to speak of construction

beginning when the roads over the mountain passes opened, bringing the trucks carrying imported

materials.

In remote areas, however, small timbers are still harvested by the carpenters during the winter, a period

when it is easier to skid logs along river beds. While many in the communities remember when trees could

be accessed within a day from their villages, in many areas carpenters now travel 3–4 days or more to access

this same material. For these carpenters, who continue to hope to be able to hand their tools and skills on to

their sons, this is a growing obstacle and concern.

During an architectural project in the remote community of Lingshed, I helped the community explore this

issue. An existing tree planting program, set up to provide fuel for the community, was expanded to include

the goal of providing a long-term supply of wood for their buildings. ere was strong local community

support for this new idea, through their recognition of the importance of traditional building as part of their

cultural values.

Eastern Tibet

Many parts of Eastern Tibet were heavily forested in the past. Yet these areas, as a result of extreme

deforestation and poor land use management practices, are beginning to su er from a lack of materials for

traditional buildings. In the1950's, with the movement of the Chinese communist government into the

region after the civil war, a forestry industry was established to tap into the rich resources of the region.

While providing some economic development, this process resulted in widespread deforestation—with at

least 60% of the region's virgin forests being clear-cut (Figure 5)—and environmental deterioration. Heavy

rainfall in the region combined with deforestation was seen as one of the major reasons for the devastating

ooding on the Yangtse and other rivers during the summer of 1998.

As a result, the Chinese government enacted a total ban on logging in the region as of 1 September 1999.

One impact of the ban has been uncertainty regarding the supply of construction materials, since the

gathering of timbers has traditionally been the responsibility of the homeowner or the monastery. In

response to this, the government has stated that individuals will still be permitted access to these resources

upon receipt of a special permit. ere is, however, no guarantee that this will occur. Conversations with

many builders showed that the future of wood supplies for their craft and livelihood was an unknown and

timber resources for building have become a di cult commodity to acquire in some villages, and are

disappearing from the larger centers.

ere are many skilled local carpenters in the region, employed to build houses and to work on the

construction and restoration of temples and monasteries. But the amount of work available for local

carpenters has been steadily decreasing, compounded by the in uence of Chinese modernism and the

dogma, which now dominates national policy, that “modernism and science” are a solution to all problems.

Traditional ways of life and knowledge are overlooked to the extent that carpenters in rural areas often view

the new glass and concrete buildings as something superior, with their own ideas being primitive.

Several options for the future of the region could be explored: agriculture, more sustainable forestry,

ecotourism, etc. Indeed, recognizing the natural beauty of the region and the value of its rich Tibetan

culture, local government o cials are now touting ecotourism as a sector to be developed as a replacement

for the battered forestry sector. Unfortunately, the new mantra of modernism has done little to prepare them

for understanding the nature of ecotourism and what travelers require in the way of services, facilities, and

cultural amenities or natural resources.

To support ecotourism, the development of long-term actions that will provide the conditions upon which

the traditional architecture of the region can be both preserved and evolve is needed. In meetings with local

o cials in this region, recommendations provided to support this included the need to:

Develop a tree planting program to control erosion and ensure the reestablishment of a rich local

biodiversity;

Encourage the establishment of small-scale village tree nurseries throughout the region to grow a

diversity of locally typical tree species;

Develop forestry policies to ensure the supply of wood products for the construction of traditional

architecture by local builders;

Establish a formal process for the training of Tibetan carpenters;

Develop design guidelines for a sustainable tourist industry, including guidelines for developing

facilities, sustainable trail systems, and nature preserves;

Provide guidelines for the protection of religious and natural sites in the region.

A brief conclusion

While it is true, especially in today's world, that cultural changes are natural and inevitable, larger issues

remain. e examples of Ladakh (where the local cultural traditions provided a mechanism for promoting

long-term land use management practices) and the QNP (where the importance of ecotourism performed

the same function) demonstrate that placing value on traditional culture is essential for developing local

plans for environmental sustainability and vice versa. It also demonstrates the use of architecture as a tool to

address the connected issues of environmental and cultural sustainability.

FIGURE 1

Logs being gathered for house addition. In eastern Tibet—where wood is plentiful and houses are

larger than in the west—houses are often referred to by the number of columns or pillars they have.

(Photo by William Semple)

FIGURE 2

e community donates labor to the rebuilding of Litang Monastery. (Photo by William Semple)

FIGURE 3

Elaborate woodwork at the entrance to the main Prayer Hall. (Photo by William Semple)

FIGURE 4

e QNP Training Center, Xegar, Tibet. e complex uses 2 courtyards, the rst for o ces and

classrooms, the second for trainee residences—a common traditional Tibetan spatial hierarchy. e

south and east orientations maximize passive solar gain. An internal walkway, connecting all parts of

the complex, provides protection to the north elevation of the complex. e design includes use of

local materials and building techniques. (Design by William Semple)

FIGURE 5

Loading logs in heavily deforested area. (Photo by Pam Logan)

Citation Download Citation

William Semple "Traditional Architecture in Tibet: Linking Issues of Environmental and Cultural

Sustainability," Mountain Research and Development 25(1), 15-19, (1 February 2005).

https://doi.org/10.1659/0276-4741(2005)025[0015:TAIT]2.0.CO;2

Published: 1 February 2005

Home About Subscribe Publisher Resources Library Resources Help Contact

Copyright © 2018 BioOne Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Group 2Document12 pagesGroup 2Abreham Fantu Welde AlmazNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Group 1Document15 pagesGroup 1Abreham Fantu Welde AlmazNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Lec 01 - Interpretation in ArchitectureDocument44 pagesLec 01 - Interpretation in ArchitectureAbreham Fantu Welde AlmazNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Assessing The Economic Value of Vernacular Architecture of Mountain Regions Using Contingent ValuationDocument1 pageAssessing The Economic Value of Vernacular Architecture of Mountain Regions Using Contingent ValuationAbreham Fantu Welde AlmazNo ratings yet

- University of Gondar Department of Architecture: Integrated Design IDocument3 pagesUniversity of Gondar Department of Architecture: Integrated Design IAbreham Fantu Welde AlmazNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Science Abrham Fantu 4106-08Document12 pagesScience Abrham Fantu 4106-08Abreham Fantu Welde AlmazNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Science Abrham Fantu 4106-08Document12 pagesScience Abrham Fantu 4106-08Abreham Fantu Welde AlmazNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Analysis PWD Rate Schedule 2014Document2,144 pagesAnalysis PWD Rate Schedule 2014dxzaber80% (10)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- Revision Unit 13 For 1st TestDocument16 pagesRevision Unit 13 For 1st TestHuỳnh Lê Quang ĐệNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Philippine Environmental LawsDocument3 pagesPhilippine Environmental LawsTano MarkNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- 13 Nu Drain Underground Drainage SystemDocument6 pages13 Nu Drain Underground Drainage SystemMahesh SavandappaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Bulk Density Moisture Density Atteberg Limits: WorksheetsDocument9 pagesBulk Density Moisture Density Atteberg Limits: WorksheetsRobert WalusimbiNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Environmental AccountingDocument27 pagesEnvironmental AccountingFaresh Haroon100% (1)

- Unit Wise FGD Implementation Status and Summary Sheet October2022Document10 pagesUnit Wise FGD Implementation Status and Summary Sheet October2022Phani Chand GangipamulaNo ratings yet

- Soal Bahasa Inggris Kelas X SMADocument2 pagesSoal Bahasa Inggris Kelas X SMAMuhammad Zeini100% (1)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Sustainable Development Defining Sustainable DevelopmentDocument5 pagesSustainable Development Defining Sustainable DevelopmentSanchit SinghalNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- FDT Form PDFDocument1 pageFDT Form PDFGenevieve GayosoNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Referat Engleza - OdtDocument4 pagesReferat Engleza - OdtGeorge StanNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Lateral Earth Pressure Cullman CompletoDocument36 pagesLateral Earth Pressure Cullman CompletoRodolfo RodriguezNo ratings yet

- Benefits of Early Rising: Value of Sports and Games in LifeDocument8 pagesBenefits of Early Rising: Value of Sports and Games in LifeArijit RoyNo ratings yet

- Rare, Threatened, and Endangered Plants of Maryland, April 2010Document33 pagesRare, Threatened, and Endangered Plants of Maryland, April 2010Maryland Native Plant ResourcesNo ratings yet

- Edward Barbier (2004) Agricultural Expansion, Resource Booms and Growth in Latin America Implications For Long-Run Economic DevelopmentDocument21 pagesEdward Barbier (2004) Agricultural Expansion, Resource Booms and Growth in Latin America Implications For Long-Run Economic DevelopmentJuanBorrellNo ratings yet

- Construction On Flexible PavementDocument16 pagesConstruction On Flexible PavementABHAY SHRIVASTAVANo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- 07 041Document8 pages07 041agrosergio2010920No ratings yet

- Whittlesey's Classification of Major Agricultural RegionsDocument11 pagesWhittlesey's Classification of Major Agricultural RegionsMariam Kareem100% (4)

- Discover The City of TokyoDocument18 pagesDiscover The City of Tokyoglamour princeNo ratings yet

- Treasure Hunting NewsDocument3 pagesTreasure Hunting NewsNes ConstanteNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

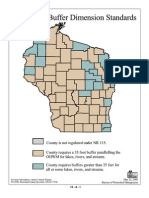

- Shoreland Vegetation - Buffer - Standards by County in WisconsinDocument29 pagesShoreland Vegetation - Buffer - Standards by County in WisconsinLori KoschnickNo ratings yet

- Red Data Book of European Butterflies (Rhopalocera) : Nature and Environment, No. 99Document259 pagesRed Data Book of European Butterflies (Rhopalocera) : Nature and Environment, No. 99TheencyclopediaNo ratings yet

- Wildlife Rehabilitation Study GuideDocument8 pagesWildlife Rehabilitation Study GuideStacie BoothNo ratings yet

- 19 - PMC For Tirupati Smart City - Monthly Progress Report - June 2019 (Year 2)Document108 pages19 - PMC For Tirupati Smart City - Monthly Progress Report - June 2019 (Year 2)Anil PuvadaNo ratings yet

- Agrarian Reform - IntroductionDocument24 pagesAgrarian Reform - Introductionrenee tanapNo ratings yet

- As 2156.1-2001 Walking Tracks Classification and SignageDocument7 pagesAs 2156.1-2001 Walking Tracks Classification and SignageSAI Global - APACNo ratings yet

- Alemayehu Book 2006 Ethiopia Groundwater Occurrence Hydrogeological Water Quality AquiferDocument107 pagesAlemayehu Book 2006 Ethiopia Groundwater Occurrence Hydrogeological Water Quality AquiferAbiued Ejigue100% (5)

- Surface Water and Ground Water Interaction: Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Water Fact SheetDocument2 pagesSurface Water and Ground Water Interaction: Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Water Fact SheetAzwanAliNo ratings yet

- Pimiento Et Al - MagnoliaResuinatifoliaDocument21 pagesPimiento Et Al - MagnoliaResuinatifoliamelisayalaNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)