Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Endodoncia Por Estudiantes

Uploaded by

carlosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Endodoncia Por Estudiantes

Uploaded by

carlosCopyright:

Available Formats

bs_bs_banner

Aust Endod J 2015; 41: 111–116

ORIGINAL RESEARCH

An overview of the endodontic curriculum in Fiji from

2009 to 2013

Arpana A. Devi, BDS, PGDip1 and Paul V. Abbott, BDS, MDS and FRACDS (ENDO)2

1 Department of Oral Health, Fiji National University, Suva, Fiji

2 School of Dentistry, University of Western Australia, Perth, Western Australia, Australia

Keywords Abstract

block teaching method, dental curriculum,

endodontic. This paper seeks to provide the reader with an overview of the endodontic

curriculum in Fiji from 2009 to 2013. It also intends to inform readers of the

Correspondence changes in endodontic teaching, the learning methods utilised, curriculum

Dr Arpana A Devi, Department of Oral Health,

development, the transition from block teaching to partial block teaching

Fiji National University, Suva, PO Box 9443, Fiji.

combined with longitudinal teaching, and the future plans for the endodontic

Email: arpana_dv@yahoo.com

module.

doi:10.1111/aej.12099

Dental education history in Fiji Fiji’s unique dental curriculum

Dentistry has been taught in Fiji since 1931, whereby Fiji has been training dentists for the past 20 years for the

some lectures about dentistry were delivered to medical country as well as for other nations within the South

students. Dentistry was a part of the medical teaching Pacific region. In 1993, a new approach to the training

program until 1945 when a 2-year clinical dental course and education of oral health personnel was introduced at

was implemented and students graduated as Assistant the then Fiji School of Medicine. Courses of study were

Dental Practitioners. To date, medical students are still designed to enable students to proceed through a

taught how to extract teeth at the College of Medicine, sequence of educational modules on a career pathway

Nursing and Health Sciences (CMNHS) at the Fiji leading from a dental assistant through other auxiliary

National University. This is largely carried out in order to levels (dental technologist, dental hygienist and dental

cater for the smaller islands in Fiji where there is no therapist) and to eventually become a dentist with a

access to dental providers for dental care. university degree (2).

The first cohort of students in dental mechanics and The courses offered were very unique when compared

dental nursing graduated in 1955. In 1968, the University to other universities as the education of dentists and the

of the South Pacific began teaching dental students in the training of auxiliaries were integrated into the same insti-

first year of their course after which they completed three tution, the content of the courses was matched to the oral

years at the Fiji School of Medicine (FSMed). Upon health-care needs of the public; the pattern of oral dis-

completion of the four years, they were awarded a eases and conditions as revealed by a national oral health

Diploma in Dental Surgery. However, this course was survey; and the local cultural, social, demographic and

abolished in 1984 and The University of Adelaide in Aus- economic factors affecting oral health in the region. The

tralia agreed to take two dental students from Fiji per year scope of the curriculum was broadened to provide appro-

into their Bachelor of Dental Surgery degree course. priate knowledge in general as well as oral health. The

These students were sponsored by the Government of uniqueness of this program allowed those in training to

Fiji. Then, in 1993, the Bachelor in Dental Surgery remain on the pathway, to step off it and enter the work-

program was re-introduced into FSMed with an innova- force at different levels, and then after gaining some

tive curriculum (1). experience, to re-enter the pathway for further training

© 2015 Australian Society of Endodontology 111

Endodontic Curriculum in Fiji A. A. Devi and P. V. Abbott

at the next level. Provision was made for progress from

Block teaching scheduling/intensive teaching format

one level to another with full credit for previous training

and experience. Movement back into the mainstream There are many modes of teaching students a concept.

and upwards from one step to the next was dependent There has been a continuous change in teaching methods

upon performance and the availability of posts within the over the years with recent innovative methods that

different South Pacific countries, as most of the graduates include technology aids, peer teaching, independent

work for their home Ministry of Health, or equivalent. A learning and more emphasis on the engagement of the

clearly defined career path was established, which students in the teaching process. The utilisation of these

allowed students to have the flexibility of choosing to creative approaches is intended to accommodate indi-

leave in the middle of the overall course with some quali- vidual learning styles so that students are able to progress

fication or to pursue the entire Bachelor’s degree and towards being a deep learner rather than a surface

graduate as a dentist. Hence, the distinctiveness of this learner.

multi-entry, multi-exit program (3). To achieve this, the curriculum has to be structured in

Where feasible, the relevant details of basic and pre- such a way that, with the resources available, all the aims

clinical disciplines – such as general anatomy, general and objectives of the curriculum are met, together with

physiology, biochemistry, oral anatomy, oral physiology, the requirements of the profession in which the graduates

general pathology, and diet and nutrition – were incor- might engage themselves.

porated into appropriate modules through problem-based Block teaching involves scheduling classes in a manner

learning rather than through the conventional teacher- that replaces the traditional 40–50 min class periods. In

oriented, subject-based didactic teaching. These subjects this type of teaching schedule, the teaching is done in an

were taught mainly in the first and second years of the overall shorter period of time but it is conducted intensely

course. within the short period. Block scheduling is a type of

Planning of the courses for each level was undertaken academic scheduling whereby each student will have a

to ensure that the curriculum satisfied the requirements smaller number of different classes per day but each class

of defined job descriptions for each level, had a strong will have longer duration. Some medical schools use

community orientation with emphasis on prevention and more ‘intensive blocks’, which means that every day for a

the promotion of oral health, incorporated where feasible set number of weeks only one module or subject is

the principles of problem-based learning and included covered. Therefore, within a period of say 3–4 weeks, a

procedures to ensure the early development of clinical whole module is focused on and completed rather than

skills (2). having a course throughout the entire academic year

The objectives and the content (topics covered) for with only a few (or less) hours per week (4). The

each teaching module were defined. The objectives were extended class time allocated and modified scheduling

matched with teaching, learning and assessment and they frameworks require a change in instructional practice (5).

were regularly reviewed. Finally, provision was made for Queen reported that a number of methodologies such as

the structure and content of all courses to be subjected to the case method, synaptic and concept attainment are

critical examination and evaluation by students, staff and well-suited to use within a block schedule (6). In terms of

external examiners. using the extended class period for science instruction,

With reviews and constant feedback from external many articles have been published in science education

examiners, the major problem that was highlighted journals focusing on creative lesson plans and time usage

was the lack of human resources for specialist subjects within a block schedule (7–15). However, Jenkins et al.

(e.g. endodontics and periodontics). In order to over- concluded from their study that the teachers in their

come this, courses that required specialist personnel for survey did not use different instructional methods based

teaching were organised as ‘block sessions’. These block upon whether they were in traditional or block schedules

sessions were provided over 1 or 2 weeks whereby (16).

invited specialists would come from abroad and teach Some schools adopt a mixed approach whereby some

the entire curriculum for that subject in this duration of modules are taught in blocks and some are taught on a

time. This meant that in order to cover the whole regular yearlong basis. The current curriculum at Fiji

subject, teaching included didactic, pre-clinical and clini- National University, Department of Oral Health follows

cal sessions in the same week(s) and often started at this approach.

8.00 a.m. and continued until 9.00 or 10.00 p.m. each There has been much discussion in the literature

day. Depending upon the courses, assessment was some- regarding the advantages and disadvantages of block

times carried out at the end of the block through a scheduling in a curriculum. Kienholz et al. stated that

written examination. block scheduling allowed students to learn material at a

112 © 2015 Australian Society of Endodontology

A. A. Devi and P. V. Abbott Endodontic Curriculum in Fiji

‘more relaxed, less frenetic pace’ and that it enhanced the classes meeting on a block schedule had 22% less in-class

‘environment for learning for both teacher and students’ time. Hence, they utilised lectures to cover the modules

(17). The Center for Education Reform debated that block in a more efficient manner and emphasised how this

teaching increases scheduling flexibility and is more con- quickened pace affected students with varied levels of

ducive to team teaching, multidisciplinary classes, labo- ability.

ratories and fieldwork (18). Day et al. commented that There are only a few large-scale studies published on

converting to a block schedule resulted in increased the effects of scheduling format. Rice et al. looked at the

attendance, decreased failure rate and an improved effect of block scheduling on achievement in mathematics

quality of instruction (11). and found that students taking part in block scheduled

Lindsay was critical of block scheduling in all areas of courses performed below those in traditional classes (27).

study, highlighting that block scheduling may not work Larger studies in schools and on different subjects have

for all subjects that require daily exposures such as math- concluded that student achievement increased with the

ematics, foreign languages and music (19). He debated introduction of block scheduling (28–30). However, the

that block scheduling resulted in gaps in knowledge when authors also noted no differences between the percent-

there was no regular reinforcement of the subject matter. ages of students passing science courses from the two

The other disadvantage highlighted was that students scheduling formats. There has not been any convincing

who are absent for even just 1 day of a block miss a evidence that a change to block scheduling leads to

considerable amount of material from that subject since 1 greater understanding or achievement by students. None

day involves 8 h of teaching, which is equivalent to four of the studies mentioned assessed outcomes of participa-

weeks of a 2 h week−1 subject. tion in a block schedule over an extended period of time

The Center for Education Reform reported that there (28–30).

was no evidence that block scheduling led to more mean- The study by Salvaterra et al. indicated that students

ingful teaching innovations that resulted in higher felt individual teachers played a much greater role in their

student achievement (18). In many cases, longer class preparation (positively or negatively) than did the sched-

periods result in meeting fewer times per week, and the uling format (5). Zepeda et al. reported that the overall

overall result is less total class time (20). The use of perceptions of block scheduling were positive among the

instructional practices better suited for traditional sched- majority of studies they reviewed, but the effect of a block

ules and the disuse of instructional practices better suited schedule on student achievement was mixed, with nearly

to block-type schedules are reasons offered for why block equal numbers of reports of positive and negative effects

scheduling plans have not produced enhancement in (31).

student achievement (21).

Endodontic block teaching schedule –

Other discussions in the literature have focused on

past and present

variations in the frequency of particular teaching formats

used in different scheduling plans, and whether or not Educators, administrators and students all strive to find a

block students were better prepared for future academic schedule that allows for greater retention of knowledge,

achievement than their peers in traditional schedules provides for adequate time and produces high academic

(22–24). achievement across all subject areas. The endodontic

In medical education, the practical component aspect is block in Fiji has been trying to achieve these aims since

equally critical to the theoretical components. Hauer et al. the BDS curriculum was established in 1993 and the first

conducted a study to compare a traditional block struc- endodontic block was conducted in 1997 by one of the

ture to a longitudinal integrated structure in a medical authors (PA), a specialist Endodontist and an academic

course to see the influence it can have on the students’ from Australia. This block has been conducted by the

clinical learning program (25). They showed that the same person almost every year since then and reports

students in the longitudinal integrated program consis- have been submitted about each visit to Fiji for the

tently developed into a doctor role with patients. The purpose of teaching endodontics.

high level of integration of longitudinal integrated stu- The initial visit to Fiji was for a 2-week block teaching

dents into care systems and their deeper relationships program in February 1997. There were two main aims of

with their preceptors and patients enhanced their moti- this visit. The first was to develop the undergraduate

vation and feelings of competence to provide patient- endodontic curriculum at the newly established School of

centred care (25). Oral Health in Suva, Fiji. Whilst there, a series of lectures

Veal highlighted that teachers reported not only ben- were presented to the second, third, fourth and fifth year

efits but also challenges and trade-offs when attempting dental students. The fifth year students also completed a

to improve classroom practice (26). He reported that pre-clinical laboratory endodontic technique course,

© 2015 Australian Society of Endodontology 113

Endodontic Curriculum in Fiji A. A. Devi and P. V. Abbott

observed clinical treatment demonstrations by the visit- Following this, the 2009 block teaching in Fiji was

ing specialist Endodontist, and commenced endodontic modified to a new format as the Fiji school employed AD

treatment on their own patients. Following this visit, as a lecturer. She was therefore available to assist with the

the local academic staff continued the endodontic course block teaching program. She was also able to deliver the

and supervised the clinical treatment of patients by majority of the basic lectures in endodontics and arrange

students in order to increase their clinical experience the pre-clinical endodontic technique course prior to the

prior to graduation. The second aim of this original visit block teaching visit. This meant that the visiting lecturer

was to provide the teaching material and to train the was able to cover the more advanced theoretical topics

local staff so that they could present the lectures and and provide some clinical teaching to the fourth year

conduct the practical and clinical courses over the dental students. In addition to this work with the under-

following years. graduate students, the visiting lecturer was able to

The next visit occurred in 2002 when the same spe- conduct a workshop for staff and interested dentists in

cialist Endodontist returned to Fiji in order to review the Suva. The main purpose of the workshop was to educate

progress of the endodontic course and to update or revise staff and dentists so they could continue to teach the

it where required. Also, the local staff member who had same philosophy and techniques as that promoted to the

presented the course from 1998 to 2001 left the school at undergraduate dental students. In particular, the extra

the end of 2001 and therefore there was no dedicated time available for lectures meant that the topic of Dental

staff member available to continue teaching this subject Traumatology could be covered in more detail and a

throughout each year. The 2002 program was presented number of other topics could also be covered with the

as a 1-week course of lectures and pre-clinical laboratory students.

exercises. An examination paper and model answers The visits in 2010 and 2011 followed the same format

were provided for the local staff to administer and grade as the 2009 visit, with the exception that one clinical

the papers. session involved the fifth year students. The remainder of

In 2004, another 1-week visit was arranged. A series of the time was spent with the fourth year students present-

lectures were presented as well as a pre-clinical program ing lectures and with one clinical session. Some time was

in endodontics. A general dental practitioner from Perth, also devoted to meeting with staff and students to discuss

who also teaches at the University of Western Australia research projects in endodontics. Some of these projects

on a part-time basis, also visited and helped to deliver this had been performed during the previous year by the fifth

program. year students and/or staff, whilst the fourth year projects

Similar lecture and pre-clinical courses were presented were still largely being planned. The projects from the

in 2005 (over 8 working days), 2006, 2007 and 2008 with previous year were being analysed and written up with

the latter three blocks being for 1 week (5 working days) the aim of submitting them to refereed dental journals for

each. Extra teaching assistance was provided by another their consideration for publication.

specialist Endodontist from Australia for these courses. The 2012 visit followed a similar format and activities

One of the early recommendations to the school in Fiji as the 2011 visit, although the fourth year students had

that arose from the block teaching courses was that it two clinical sessions with the visiting endodontist.

would be highly desirable to have a permanent staff Further modifications were made for the 2013 visit also to

member with advanced training and endodontic exper- include two clinical sessions with both the fourth and the

tise working on a full-time basis in order to provide the fifth year students (32).

ongoing teaching of the subject and to provide consistent

Assessments following block scheduling

clinical supervision. The lack of consistency in clinical

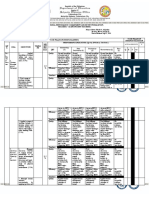

teaching was one of the disadvantages noted with the The major assessments in the block schedule from 1997

block teaching system using visiting teachers. Fortu- to 2011 were:

nately, in 2008, a local dentist (co-author, AD) was able to • Pre-clinical laboratory work 40%.

spend the academic year undertaking a Graduate • End of block written examination 60%.

Diploma in Dental Studies at the School of Dentistry of • Both forms of assessment had a pass mark of 50%.

The University of Western Australia. This full-time course In 2011, the school had a major review of its entire

included didactic, clinical and research work and it was curriculum and an external facilitator was hired to review

supervised by the same Endodontist (PA) who visits the curriculum outlines, including the endodontic cur-

Fiji. Other visiting endodontists, who teach at the school, riculum. At the same time, the school decided to intro-

and senior clinical staff in other specialty disciplines and duce competency-based assessment, and hence, this was

in general dentistry were also available for advice and incorporated as one of the major assessments for the

assistance. students. The module assessment thus changed to that

114 © 2015 Australian Society of Endodontology

A. A. Devi and P. V. Abbott Endodontic Curriculum in Fiji

outlined below. In addition, the endodontic course for teaching in a developing country such as Fiji, where

extended over two years so students could be constantly the educational institution does not have the human

engaged in activities to ensure they master the concepts resources to teach specialty subjects, needs to be evalu-

and procedures required in the theory and clinical prac- ated. Currently, there has been no evaluation of the

tice of endodontics. program in terms of teaching and learning outcomes

The assessments with a pass mark of 50% each were: since the program was introduced. There has been anec-

2011 dotal evidence from alumni that this teaching method

Semester 1 (Year 4 BDS) was beneficial to them to some extent. However, the

• Pre-clinical laboratory work 15%. major disadvantage of teaching in this manner was

• End of block written examination 40%. re-emphasised by graduates, whereby some subjects

Semester 2 taught by block sessions did not have the reinforcing

• Assignment 2: 5% (Practical application through through regular work using information that had been

models or essays). imparted in the block teaching sessions. This sometimes

Semester 3 (Year 5 BDS). led graduates to not feel confident in carrying out these

• Reflective writing for clinical cases 6% (contributing procedures as they felt there was a gap in their knowledge

towards General Dental Practice). and clinical experience.

Semester 4 Evaluation is widely acknowledged as a powerful

• Competency assessment (Year 5). means of improving the quality of education and hence

• Clinical work (6 cases) 40%. the way forward for any institution. Evaluation is univer-

sally accepted as an integral part of teaching and learning.

It is one of the basic components of any curriculum and

Future endodontic teaching in Fiji

plays a pivotal role in determining what learners learn

The 2004 Fiji National Oral Health Survey was published and what teacher’s teach (34).

in 2007 and depicts the current disease burden. Dental The next step for the school is to evaluate the block

caries is very prevalent among the Fijian people, with teaching method as used in the Department of Oral

88.3% of 6 year olds having dental caries, of which Health by the block conveners, both local and interna-

85.2% were still active and not treated. In the permanent tional. This will indicate whether there is a need to

dentitions of older age groups, the percentage of those change the program structure drastically or whether

affected by caries rose from 52.3% among 12 year olds to improvements can be made to the existing structure. The

67.5%, 98.1% and 99.5% among 15–19, 35–44 and block teaching model is an interesting model, and if

55–64 year olds, respectively (33). evaluation shows it is working, then other Universities

These survey results highlight that the caries burden is could utilise it in the absence of appropriately trained

very high in the Fijian communities. Therefore, given full-time academics.

that one of the treatment options for caries is root canal

treatment, the school as the teaching institution needs to References

prepare students to provide root canal treatment as an

option. However, in order to provide such education, it is 1. Lander H, Miles V. Fiji school of medicine: a brief

essential to have the appropriate academic staff available history and list of graduates. Sydney: University of New

South Wales; 1992.

on a full-time basis.

2. Davies GN, Atalifo SF, Tuisuva J et al. A new approach

The ideal academic person for the school is someone

to the training and education of oral health personnel.

with at least a specialty degree in endodontics who can

N Z Dent J 1993; 89: 113–8.

develop postgraduate courses in this specialty field. Such

3. King TV. Dental education in Fiji. [Cited 8 Nov 2013.]

courses could be in the form of continuing professional

Available from URL: http://ses.library.usyd.edu.au/

development courses for dentists who wish to improve

bitstream/2123/4895/2/0728_part2.pdf.1994

their knowledge and clinical skills, or they could be more 4. Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Block scheduling.

formal university-based higher level Graduate Diploma [Cited 8 Nov 2013.] Available from URL: http://

or Master’s degree level courses for dentists to become en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Block_scheduling

specialist Endodontists. 5. Salvaterra M, Lare D, Gnall J, Adams D. Block schedul-

ing: students’ perception of readiness for college math,

Outcomes and the way forward science, and foreign language. Am Secondary School

Educ 1999; 27 (4): 13–21.

The literature on block teaching is quiet polarised. Hence, 6. Queen JA. Block scheduling revisited. Phi Delta Kappan

the perception that the block teaching model is suitable 2000; 82 (3): 214–22.

© 2015 Australian Society of Endodontology 115

Endodontic Curriculum in Fiji A. A. Devi and P. V. Abbott

7. Barnes R, Straton J, Ukena M. A lesson in block sched- 22. Knight S, DeLeon N, Smith R. Using multiple data

uling. Sci Teach 1996; 63: 35. sources to evaluate an alternative scheduling model.

8. Bohince J. Blockbuster ideas. Sci Teach 1996; 63: High School J 1999; 83 (1): 1–13.

20–4. 23. Lawrence W, McPherson D. A comparative study of

9. Cooper SL. Blocking in success. Sci Teach 1996; 63: block scheduling and traditional scheduling on academic

28–31. achievement. J Instr Psychol 2000; 27 (3): 178–82.

10. Craven S. Teaching chemistry in the block schedule. 24. Dickson K, Bird K, Newman M, Kalra N. What is the

J Chem Educ 2001; 78 (4): 488–90. effect of block scheduling on academic achievement. A

11. Day MM, Ivanov CP, Binkley S. Tackling block schedul- systematic review. Report No. 1802R. London, UK: EPPI-

ing. Sci Teach 1996; 63: 25–7. Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Educa-

12. Frank M. Thinking outside the block. Sci Teach 2002; tion, University of London; 2010. [Cited November

69 (2): 38–41. 2013.] Available from URL: http://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/reel/

13. Rapp CS. Laser holography. Sci Teach 1997; 64: 38–42. 25. Hauer KE, Hirsh D, Ma I et al. The role of role: learning

14. Kristen MD, Robert HT, Philip MS. Traditional and block in longitudinal integrated and traditional block

scheduling for college science preparation: a comparison clerkships. Med Educ 2012; 46 (7): 698–710.

of college science success of students who report differ- 26. Veal W. Teaching and student achievement in science: a

ent high school scheduling plans. High School J April/ comparison of three different schedule types. J Sci Teach

May 2006; 89 (4): 22–33. Educn 2000; 11 (3): 251–75.

15. National Education Commission on Time and Learning. 27. Rice JK, Croninger RG, Roellke CF. The effect of block

Prisoner of time: report of the national education com- scheduling high school mathematics courses on student

mission on time and learning. Washington DC: U.S. achievement and teachers’ use of time: implications for

Government Printing Office; 1994. educational productivity. Econ Educ Rev 2002; 21: 599–

16. Jenkins E, Queen A, Algozzine B. To block or not to 607.

block: that’s not the question. J Educ Res 2002; 95 (4): 28. Deuel LS. Block scheduling in large, urban high schools:

196–202. effects on academic achievement, student behavior, and

17. Kienholz K, Segall N, Yellin D. The block: implications staff perceptions. High School J 1999; 83 (1): 14–25.

for secondary teachers. Kappa Delta Pi Record 2003; 29. Nichols JD. Block-scheduled high schools: impact on

2 (39): 62–5. achievement in English and language arts. J Educ Res

18. Center for Education Reform. Scheduling: on the block, 2005; 98 (5): 299–309.

1996. [Cited 8 Nov 2013.] Available from URL: http:// 30. Adam VM, Kirsten MD, Robert HT, Sadler PM. Breaking

www.edreform.com/index.cfm?fuseAction=document from traditaion: unfulfilled promises of block scheduling

&documentID=667 in science. Sci Educ 2007; 16 (1): 1–8.

19. Lindsay J. ‘The problem with block scheduling’. The case 31. Zepeda SJ, Mayers RS. An analysis of research on block

against block scheduling. 2000. [Cited 8 Nov 2013.] scheduling. Rev Educ Res 2006; 76: 137–70.

Available from URL: http://www.jefflindsaycom/ 32. Abbott PV. Report of a visit to the Fiji Department of

Block.shtml Oral Health within the Fiji National University. 5–9

20. Louden CK, Hounshell PB. Student-centered scheduling. August 2013.

Sci Teach 1998; 65 (6): 50–4. 33. Ministry of Health. The National Oral Health Report Fiji

21. Hackmann DG, Schmitt DM. Strategies for teaching Islands, 2004.

in a block-of-time schedule. NASSP Bull 1997; 81 (588): 34. Mamta GJ. Curricular reform in schools: the importance

1–9. of evaluation. Curriculum Stud 2004; 36 (3): 361–79.

116 © 2015 Australian Society of Endodontology

You might also like

- BDS Curriculum 2016, KuDocument242 pagesBDS Curriculum 2016, Kuanakinra well0% (1)

- BDS Curriculum (1st Year - Final Year) RGUHSDocument177 pagesBDS Curriculum (1st Year - Final Year) RGUHSdocakshay9288% (8)

- Combination DLL Problem SolvingDocument6 pagesCombination DLL Problem SolvingJessica MacagalingNo ratings yet

- Rotation PlanDocument11 pagesRotation Planswethashaki96% (23)

- BSN III 2 Group 3 FinalDocument55 pagesBSN III 2 Group 3 FinalCharinaNo ratings yet

- Kuhas Bds SyllabusDocument127 pagesKuhas Bds SyllabusDrAjey BhatNo ratings yet

- Internal Stakeholders' Feedback On The Senior High School Curriculum Under TVL TrackDocument28 pagesInternal Stakeholders' Feedback On The Senior High School Curriculum Under TVL TrackJojimar Julian100% (2)

- Kerosuo 2001Document8 pagesKerosuo 2001nemichi samiNo ratings yet

- Problem-Based Learning: An Interdisciplinary Approach in Clinical TeachingDocument6 pagesProblem-Based Learning: An Interdisciplinary Approach in Clinical TeachingArdianNo ratings yet

- Student Perspective of Classroom and Distance Learning During COVID-19 Pandemic in The Undergraduate Dental Study Program Universitas IndonesiaDocument16 pagesStudent Perspective of Classroom and Distance Learning During COVID-19 Pandemic in The Undergraduate Dental Study Program Universitas IndonesiaFifi FruitasariNo ratings yet

- Improving Assessment in Dental Education Through A Paradigm of Comprehensive Care: A Case ReportDocument13 pagesImproving Assessment in Dental Education Through A Paradigm of Comprehensive Care: A Case ReportfidelbustamiNo ratings yet

- SamihussDocument7 pagesSamihussNader ElbokleNo ratings yet

- Yiu 2011Document10 pagesYiu 2011Chris MartinNo ratings yet

- Contemporary Undergraduate Implant Dentistry Education A Systematic ReviewDocument13 pagesContemporary Undergraduate Implant Dentistry Education A Systematic ReviewfloraNo ratings yet

- BDS Curriculum 2016Document242 pagesBDS Curriculum 2016BishowNo ratings yet

- Research Article: Preparedness and Practice Management Skills of Graduating Dental Students Entering The Work ForceDocument8 pagesResearch Article: Preparedness and Practice Management Skills of Graduating Dental Students Entering The Work ForceNurul HusnaNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Undergraduate Dental Education Curriculum (BDS)Document248 pagesGuidelines For Undergraduate Dental Education Curriculum (BDS)aamnashah25100% (1)

- BDS Syllabus 2011Document125 pagesBDS Syllabus 2011Shyam KrishnanNo ratings yet

- A Clinically Oriented Complete Denture Program For Second-Year Dental StudentsDocument8 pagesA Clinically Oriented Complete Denture Program For Second-Year Dental StudentsBrijesh MaskeyNo ratings yet

- BDS Curriculum 2016Document302 pagesBDS Curriculum 2016FireFrostNo ratings yet

- Eur J Dental Education - 2017 - Field - The Graduating European Dentist A New Undergraduate Curriculum FrameworkDocument9 pagesEur J Dental Education - 2017 - Field - The Graduating European Dentist A New Undergraduate Curriculum FrameworkHernández Becerra Ivanna PaolaNo ratings yet

- Periodontology A Neglected Field of DentDocument3 pagesPeriodontology A Neglected Field of DentMinahil SherNo ratings yet

- BDS Regulations HAND BOOK 2013-14 PDFDocument135 pagesBDS Regulations HAND BOOK 2013-14 PDFSayeeda MohammedNo ratings yet

- DentalDocument2 pagesDentalntambik210% (1)

- Edited Flipped ClassroomDocument58 pagesEdited Flipped ClassroomJonathan Agcaoili KupahuNo ratings yet

- Student Perspective of Classroom and Distance Learning During COVID-19 Pandemic in The Undergraduate Dental Study Program Universitas IndonesiaDocument8 pagesStudent Perspective of Classroom and Distance Learning During COVID-19 Pandemic in The Undergraduate Dental Study Program Universitas IndonesiaF-z ImaneNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning 6.2013Document20 pagesTeaching and Learning 6.2013fatinfiqahNo ratings yet

- Accessibility of Deaf Education in The Mainstream Certificate Program of A Private Tertiary Educational Institution in Manila PDFDocument14 pagesAccessibility of Deaf Education in The Mainstream Certificate Program of A Private Tertiary Educational Institution in Manila PDFFlorence Lloyd UbaldoNo ratings yet

- bds2013 14Document135 pagesbds2013 14Mohammed ArshadNo ratings yet

- Badovinac 2013Document8 pagesBadovinac 2013Naji Z. ArandiNo ratings yet

- University of Sheffield Bachelor of Dental Surgery BrochureDocument12 pagesUniversity of Sheffield Bachelor of Dental Surgery BrochureYoussef MaharemNo ratings yet

- Oral Health Education Improved Oral Health KnowledgeDocument11 pagesOral Health Education Improved Oral Health KnowledgeGita PratamaNo ratings yet

- B.D.S Curriculum (2016) UDMY UDMM MyanmarDocument331 pagesB.D.S Curriculum (2016) UDMY UDMM MyanmarNay AungNo ratings yet

- Kyushu Dental University Graduate School of DentistryDocument18 pagesKyushu Dental University Graduate School of DentistryAlex KwokNo ratings yet

- Emerging Physical Education Teaching Strategies and Students' Academic Performance: Basis For A Development ProgramDocument13 pagesEmerging Physical Education Teaching Strategies and Students' Academic Performance: Basis For A Development ProgramPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Feasibility and Sustainability of An Interactive Team-Based Learning Method For Medical Education During A Severe Faculty Shortage in ZimbabweDocument5 pagesFeasibility and Sustainability of An Interactive Team-Based Learning Method For Medical Education During A Severe Faculty Shortage in ZimbabweAffan ElahiNo ratings yet

- Students Perceptions of Effective Classroom and CDocument13 pagesStudents Perceptions of Effective Classroom and Ckrishnabhagwat30No ratings yet

- Bds Syllabus - 240115 - 193609Document111 pagesBds Syllabus - 240115 - 193609poojamb218No ratings yet

- There's A Lot of Learning Going On But NOT Much Teaching!': Student Perceptions of Problem-Based Learning in ScienceDocument17 pagesThere's A Lot of Learning Going On But NOT Much Teaching!': Student Perceptions of Problem-Based Learning in ScienceNur Amani Abdul RaniNo ratings yet

- STUDY GUIDE Final 11 Oral PathologyDocument44 pagesSTUDY GUIDE Final 11 Oral PathologyShahid HameedNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Oral BiologyDocument55 pagesCurriculum Oral BiologyJohn SmithNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument320 pagesUntitledRODRIGO EDUARDO SANTIBÁÑEZ ABRAHAMNo ratings yet

- Executive Summary - Bakson HMCDocument19 pagesExecutive Summary - Bakson HMCamitNo ratings yet

- 1hassessment1Document10 pages1hassessment1api-357444414No ratings yet

- OA3093 - Peer To Peer Clinical Teaching by Medical Students in The Formal CurriculumDocument10 pagesOA3093 - Peer To Peer Clinical Teaching by Medical Students in The Formal CurriculumAmmarah OmerNo ratings yet

- School Dental Health ProgramsDocument4 pagesSchool Dental Health ProgramsSaugat DasNo ratings yet

- GuidlinesDocument10 pagesGuidlinesbubuvulpeaNo ratings yet

- 2020 Article 2312-DikonversiDocument12 pages2020 Article 2312-DikonversiDhahlul Fikri UmmiyuddinNo ratings yet

- School Dental Health Programme Pedo 2Document25 pagesSchool Dental Health Programme Pedo 2misdduaaNo ratings yet

- Biology Curriculum 2010 WebDocument238 pagesBiology Curriculum 2010 WebjayzebraNo ratings yet

- Navaz Sama CitationDocument22 pagesNavaz Sama CitationMoahmed NavazNo ratings yet

- The Graduating European Dentist: Contemporaneous Methods of Teaching, Learning and Assessment in Dental Undergraduate EducationDocument8 pagesThe Graduating European Dentist: Contemporaneous Methods of Teaching, Learning and Assessment in Dental Undergraduate Educationalvin fauziyahNo ratings yet

- Course ReflectionDocument3 pagesCourse ReflectionIvy Grace HusmilloNo ratings yet

- Difficulties in Learning English Faced by VisuallyDocument18 pagesDifficulties in Learning English Faced by VisuallyDario JavierNo ratings yet

- Needs Analysis: Esp Syllabus Design For Indonesian Efl Nursing StudentsDocument11 pagesNeeds Analysis: Esp Syllabus Design For Indonesian Efl Nursing StudentsFitraAshariNo ratings yet

- Impact Evaluation of A School-Based Oral Health Program Kuwait National ProgramDocument9 pagesImpact Evaluation of A School-Based Oral Health Program Kuwait National ProgramLeo AlbertoNo ratings yet

- Implant Dentistry: Postgraduate DiplomaDocument10 pagesImplant Dentistry: Postgraduate DiplomaAudgan97No ratings yet

- Combining Chalk Talk With Powerpoint To Increase In-Class Student EngagementDocument13 pagesCombining Chalk Talk With Powerpoint To Increase In-Class Student EngagementJuan Augusto Fernández TarazonaNo ratings yet

- Dpb40093 Business Communication Report Title: Online Learning Group Name: Dream Killer Group Members NameDocument12 pagesDpb40093 Business Communication Report Title: Online Learning Group Name: Dream Killer Group Members Namemoneesha sriNo ratings yet

- PCL Dental Science, 2065Document85 pagesPCL Dental Science, 2065bibekghale8588No ratings yet

- Mohamed Omaia, Maged Negm, Yousra Nashaat, Nehal Nabil, Amal OthmanDocument11 pagesMohamed Omaia, Maged Negm, Yousra Nashaat, Nehal Nabil, Amal OthmancarlosNo ratings yet

- Acute Renal Failure in Four HIV-infected Patients: Potential Association With Tenofovir and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory DrugsDocument2 pagesAcute Renal Failure in Four HIV-infected Patients: Potential Association With Tenofovir and Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory DrugscarlosNo ratings yet

- ICH GCP PrinciplesDocument1 pageICH GCP PrinciplescarlosNo ratings yet

- Endodontic Materials: R. Scott Gatewood, DMDDocument18 pagesEndodontic Materials: R. Scott Gatewood, DMDcarlosNo ratings yet

- KHDA - Dubai Arabian American Private School 2015 2016Document27 pagesKHDA - Dubai Arabian American Private School 2015 2016Edarabia.comNo ratings yet

- SOP SampleDocument2 pagesSOP SampleRonak ShahNo ratings yet

- Peac Documentation Checklist: Folder A: School Philosophy, Vision, Mission, Goals/Objectives Exhibits/DocumentsDocument3 pagesPeac Documentation Checklist: Folder A: School Philosophy, Vision, Mission, Goals/Objectives Exhibits/DocumentsMark Charle Mana100% (3)

- Ipcrf Joshua Servito UnratedDocument8 pagesIpcrf Joshua Servito UnratedJoshua ServitoNo ratings yet

- Teaching As ProfessionDocument63 pagesTeaching As ProfessionJayCesar50% (2)

- Reference Letter From Laura CronenDocument2 pagesReference Letter From Laura Cronenapi-318149717No ratings yet

- Science and Technology: Grade 10Document200 pagesScience and Technology: Grade 10DeviBhaktaDevkotaNo ratings yet

- The Problem and A Review of LiteratureDocument43 pagesThe Problem and A Review of LiteratureDianne AlonteNo ratings yet

- Financial Planning Education FrameworkDocument46 pagesFinancial Planning Education FrameworkdizhangNo ratings yet

- Bo TreeDocument40 pagesBo TreeGurram SrihariNo ratings yet

- FamilyDocument2 pagesFamilypearllavenderNo ratings yet

- RRL Books 1Document9 pagesRRL Books 1Jessica Christel MaglalangNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Teaching Elementary ScienceDocument34 pagesA Guide To Teaching Elementary ScienceJohn Little Light80% (5)

- The Post Method EraDocument2 pagesThe Post Method EraRifkyNo ratings yet

- Determining Main Idea and Supporting Details - Wild in The City - PBS LearningMediaDocument3 pagesDetermining Main Idea and Supporting Details - Wild in The City - PBS LearningMediaCarita HemsleyNo ratings yet

- Guide To Tripods 7Cs Framework of Effective TeachingDocument19 pagesGuide To Tripods 7Cs Framework of Effective TeachingChipelibreNo ratings yet

- APPENDIX C and BDocument11 pagesAPPENDIX C and BCHERIE ANN APRIL SULITNo ratings yet

- ERP in Undergraduate CurriculumDocument7 pagesERP in Undergraduate CurriculumErick EspirituNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Advanced Philosophy Updated 2022 1Document6 pagesSyllabus Advanced Philosophy Updated 2022 1eugene louie ibarraNo ratings yet

- B. Ed Research Project FullDocument96 pagesB. Ed Research Project Fullsaharsaeed100% (2)

- Dealism: EfinitionsDocument13 pagesDealism: EfinitionsLady Paul SyNo ratings yet

- Sociological-Perspectives-in-Education LONG QUIZDocument29 pagesSociological-Perspectives-in-Education LONG QUIZJea Mae G. BatiancilaNo ratings yet

- Sdm-Mbbs 1st Year-SyllabusDocument160 pagesSdm-Mbbs 1st Year-SyllabusVinayaka SPNo ratings yet

- G50S003 3 NCS PDFDocument173 pagesG50S003 3 NCS PDFChandraranga De SilvaNo ratings yet

- Pgce Professional Studies Study Guide 2023Document7 pagesPgce Professional Studies Study Guide 2023Lusanda MzimaneNo ratings yet

- Evaluating The Integration of Technology and Second Language LearningDocument38 pagesEvaluating The Integration of Technology and Second Language Learningpaus Yohanes PaulusNo ratings yet

- Grade 2 DLL Math 2 q4 Week 1Document10 pagesGrade 2 DLL Math 2 q4 Week 1MARY KENNETH SILVOSANo ratings yet

- Sambajon - ValEdDocument2 pagesSambajon - ValEdRoselle SambajonNo ratings yet

- Slac 2022-2023Document4 pagesSlac 2022-2023Ike SamuelNo ratings yet