Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Inquirer 2

Uploaded by

tgshkOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Inquirer 2

Uploaded by

tgshkCopyright:

Available Formats

A President who vowed that “not even a whiff of corruption” would be tolerated in his

term will not like what an international corruption watchdog has determined halfway

through his tenure—that he’s failing at the promise big-time. According to the 2019

Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) of Transparency International (TI), corruption in

the Philippines is becoming worse, not easing up. In fact, the country now ranks among

the most corrupt countries in the world. Out of 180 countries surveyed, the Philippines

came in at number 113, several notches below its ranking in previous years: 14 slots

down from 2018, 18 down from 2015, and its lowest ranking since 2012. Dirtier and

dirtier the country’s affairs seem to be getting—or at least that’s the consensus among

those polled by the TI, which reviews countries and territories through experts’ and

businessmen’s perception of government corruption.

Malacañang, quick to take umbrage at any hint of criticism from international bodies,

seemed among the least surprised at the results this time. Instead of bothering to work

up an indignant denial, presidential spokesperson Salvador Panelo offered what

sounded like a begrudging acknowledgment that the problem has indeed been hard to

lick.

The President’s hands are “tied by the due process clause of the Constitution,” this

“tedious process that demands evidence to get dishonest officials out of power,” Panelo

claimed. “We’ve been fighting corruption and the President has been firing top

government officials… (who) have been charged in the Ombudsman and in the courts.”

Yes, he has—but mostly those conveniently not close to him, who don’t have his ear,

or are far down the governmental totem pole. The list of recycled favored officials,

however, tell a different story. There’s former Customs chief Nicanor Faeldon, who

“resigned” after a P6.4-billion shipment of crystal meth managed to slip into the country

in 2017, but was then appointed to the Bureau of Corrections (where he also made a

royal mess). Faeldon’s successor, Isidro Lapeña, was relieved as customs chief after

allegations that some P11-billion worth of shabu were smuggled inside magnetic lifters

during his watch—but was just as quickly ensconced at Tesda, the government agency

for technical and vocational training. A presidential free pass for the two, while it was

the lowly warehouse caretaker in the P6.4-billion drug smuggling case that was thrown

in jail.

That selective anticorruption campaign blights as well the fate of government

transactions that have all the earmarks of conflict of interest, such as the multimillion

security services deals the company owned by Solicitor General Jose Calida’s wife

Milagros had clinched with at least three government agencies. Rather than enforcing

the Code of Ethics prohibiting conflict of interest among public officials, however, the

President even defended Calida: “Why should I fire him? He’s good. And doesn’t he

have a right to go into business?”

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Letter Request Correction of Lot NumberDocument1 pageLetter Request Correction of Lot Numbertgshk100% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Alumni Homecoming 2019 ScriptDocument7 pagesAlumni Homecoming 2019 Scripttgshk50% (2)

- Special Power of Attorney BirDocument1 pageSpecial Power of Attorney BirtgshkNo ratings yet

- Deed of Sale Louie MangampatDocument1 pageDeed of Sale Louie MangampattgshkNo ratings yet

- VillarDocument2 pagesVillartgshkNo ratings yet

- Drilon: Mislatel Franchise Considered Revoked For Violating ConditionsDocument1 pageDrilon: Mislatel Franchise Considered Revoked For Violating ConditionstgshkNo ratings yet

- When Is There A Lawful Warrantless Arrest?Document1 pageWhen Is There A Lawful Warrantless Arrest?tgshkNo ratings yet

- Dr. Najeebuddin Ahmed: 969 Canterbury Road, Lakemba, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2195Document2 pagesDr. Najeebuddin Ahmed: 969 Canterbury Road, Lakemba, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2195Najeebuddin AhmedNo ratings yet

- Ticket Udupi To MumbaiDocument2 pagesTicket Udupi To MumbaikittushuklaNo ratings yet

- Product Guide TrioDocument32 pagesProduct Guide Triomarcosandia1974No ratings yet

- Human Resource Management by John Ivancevich PDFDocument656 pagesHuman Resource Management by John Ivancevich PDFHaroldM.MagallanesNo ratings yet

- Tate Modern London, Pay Congestion ChargeDocument6 pagesTate Modern London, Pay Congestion ChargeCongestionChargeNo ratings yet

- Icom IC F5021 F6021 ManualDocument24 pagesIcom IC F5021 F6021 ManualAyam ZebossNo ratings yet

- 7Document101 pages7Navindra JaggernauthNo ratings yet

- Design & Construction of New River Bridge On Mula RiverDocument133 pagesDesign & Construction of New River Bridge On Mula RiverJalal TamboliNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Searching and PlanningDocument104 pagesChapter 3 Searching and PlanningTemesgenNo ratings yet

- Your Electronic Ticket ReceiptDocument2 pagesYour Electronic Ticket Receiptjoana12No ratings yet

- Customer Satisfaction-ICICI Bank-Priyanka DhamijaDocument85 pagesCustomer Satisfaction-ICICI Bank-Priyanka DhamijaVarun GuptaNo ratings yet

- (ENG) Visual Logic Robot ProgrammingDocument261 pages(ENG) Visual Logic Robot ProgrammingAbel Chaiña Gonzales100% (1)

- Delta PresentationDocument36 pagesDelta Presentationarch_ianNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument8 pagesRetrieveSahian Montserrat Angeles HortaNo ratings yet

- CavinKare Karthika ShampooDocument2 pagesCavinKare Karthika Shampoo20BCO602 ABINAYA MNo ratings yet

- Design of Flyback Transformers and Filter Inductor by Lioyd H.dixon, Jr. Slup076Document11 pagesDesign of Flyback Transformers and Filter Inductor by Lioyd H.dixon, Jr. Slup076Burlacu AndreiNo ratings yet

- Pro Tools ShortcutsDocument5 pagesPro Tools ShortcutsSteveJones100% (1)

- Data Mining - Exercise 2Document30 pagesData Mining - Exercise 2Kiều Trần Nguyễn DiễmNo ratings yet

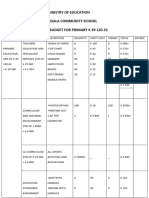

- Ministry of Education Musala SCHDocument5 pagesMinistry of Education Musala SCHlaonimosesNo ratings yet

- 3.13 Regional TransportationDocument23 pages3.13 Regional TransportationRonillo MapulaNo ratings yet

- Paul Milgran - A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual DisplaysDocument11 pagesPaul Milgran - A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual DisplaysPresencaVirtual100% (1)

- Certification and LettersDocument6 pagesCertification and LettersReimar FerrarenNo ratings yet

- Circuitos Digitales III: #IncludeDocument2 pagesCircuitos Digitales III: #IncludeCristiamNo ratings yet

- Exercise 23 - Sulfur OintmentDocument4 pagesExercise 23 - Sulfur OintmentmaimaiNo ratings yet

- Chapter Two Complexity AnalysisDocument40 pagesChapter Two Complexity AnalysisSoressa HassenNo ratings yet

- Shopnil Tower 45KVA EicherDocument4 pagesShopnil Tower 45KVA EicherBrown builderNo ratings yet

- Dynamics of Interest Rate and Equity VolatilityDocument9 pagesDynamics of Interest Rate and Equity VolatilityZhenhuan SongNo ratings yet

- Unit 5 Andhra Pradesh.Document18 pagesUnit 5 Andhra Pradesh.Charu ModiNo ratings yet

- WhatsApp Chat With JioCareDocument97 pagesWhatsApp Chat With JioCareYásh GúptàNo ratings yet

- Kicks: This Brochure Reflects The Product Information For The 2020 Kicks. 2021 Kicks Brochure Coming SoonDocument8 pagesKicks: This Brochure Reflects The Product Information For The 2020 Kicks. 2021 Kicks Brochure Coming SoonYudyChenNo ratings yet