Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Effect of Smoking On Salivary Rate Flow

Uploaded by

Yodi WijayaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Effect of Smoking On Salivary Rate Flow

Uploaded by

Yodi WijayaCopyright:

Available Formats

Effect of smoking on salivary flow rate

ORIGINAL ARTICLE

EFFECT OF SMOKING ON SALIVARY FLOW RATE

Ghulam Jillani Khan, Muhammad Javed, Muhammad Ishaq

Department of Physiology & Anatomy, Khyber Medical College and

Department of Physiology, Kabir Medical College, Peshawar, Pakistan

ABSTRACT

Background: The smoke of tobacco during smoking is spread to all parts of the oral cavity and therefore,

the taste receptors, a primary receptor site for salivary secretion, are constantly exposed. Generally it is

accepted that long term use of tobacco decreases the sensitivity of taste receptors which in turn leads to

depressed salivary reflex. Presumably, this might lead to altered taste receptors response and hence to

changes in salivary flow rate. The present study was designed to document these changes, if any.

Methodology: Subjects of the study were divided into smokers, and controls. Each group comprised of 20

healthy male adults. The saliva of each subject was collected under resting condition and following applica-

tion of crude nicotine and citric acid solution to the tip of tongue.

Results: After stimulation with both nicotine and citric acid, all subjects of each group showed a high

increase in salivary flow rate. Salivary flow rates of smokers were not much different from that of non-

smokers.

Conclusion: Long-term smoking does not adversely affect the taste receptors response and hence salivary

flow rate.

KEY WORDS: Saliva, Salivary flow rate, Smoking.

INTRODUCTION It has been discovered that smoking in-

creases the activity of salivary glands and, indeed,

Saliva, the fluid in the mouth, is a combined this observation has been made by every one who

secretion of the three pairs of salivary glands: the begins smoking. It has also been observed that

parotid, the submandibular and the sublingual; some tolerance develops to the salivatory effects

together with numerous small glands.1 It is the most of smoking because habitual smokers do not sali-

easily accessible fluid in the human body and in vate as do novice smokers in response to smok-

future it is probable that it will provide an easy ing.6 But in a study it was noted that there is no

tool for non-invasive measurements of various body difference in the secretion rate of saliva between

parameters.2 Approximately 0.5 liters of saliva is smokers and non-smokers, however it was also

secreted per day. The salivary flow rates are seen that regular but not immediate smoking did

0.3 ml per minute when unstimulated and rise to not cause any significant change in the salivary

1.5-2.0 ml per minute when stimulated but flow flow rate.7,8 In an experiment it was discovered that

rate is negligible during night.3 In normal individu- application of nicotine and citric acid solutions at

als saliva is secreted in two stages; first, secretion different locations to the tongue increases saliva-

occurs into the glandular acini which is approxi- tion but with different taste sensations.9

mately similar to extracellular fluid (ECF), then this

primary secre-tion flows through the acinar ducts Generally it is accepted that long term use

where re-conditioning occurs.4 In addition, the dif- of tobacco decrease the sensitivity of taste recep-

ferences in the function of excretion and the role tors which in turn leads to depressed salivary re-

of excretory duct cells are currently unknown in flex. Presumably, this might lead to altered taste

salivary glands.5 receptors response and hence to changes in sali-

vary flow rates. Therefore, the present study was

About all methods of tobacco use, predomi- designed to document these changes, if any.

nantly smoking is linked to mouth and it is the

smoke of tobacco which spreads to about all parts MATERIAL AND METHODS

of the oral cavity and therefore, the taste recep-

tors, a primary receptor site for salivary secretion, The subjects of the study were selected from

are constantly exposed to this smoke during the the students of Basic Medical Sciences Institute

smoking process. (BMSI), Jinnah Post Graduate Medical Centre

Gomal Journal of Medical Sciences July-December 2010, Vol. 8, No. 2 221

Ghulam Jillani Khan, et al.

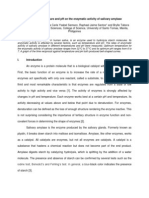

(JPMC) and the general population of Karachi. The Table 1: Comparison of salivary flow rates of

subjects were divided into two groups; smokers smokers and non-smokers as controls before

and non-smokers as controls. Each group com- and after stimulation with nicotine and citric

prised of 20 apparently healthy male adults. All acid solutions.

the subjects were well matched with respective to

Smokers Smokers Smokers

age (25-30 years) and the duration of beginning

(res) (nic) (cit)

smoking (5-7 years). Subjects in the habit of more

than one type of tobacco use or bad orodontal 0.5 0.53 0.85

hygiene or with too little salivary secretion were

0.5 0.59 0.81

not included in the study. Before sampling, each

subject was briefed about the procedure and in- 0.48 0.71 0.74

structed to wash his mouth and gargle with plain

0.46 0.7 0.62

water. The saliva of each subject was collected for

10 minutes under resting condition and following 0.46 0.62 0.54

application of crude nicotine solution (50 ml of

0.5 0.52 0.49

1% v/v) and citric acid solution (50 ml of 1% w/v)

to the tip of his tongue. Crude nicotine was ex- 0.49 0.46 0.51

tracted from tobacco10 and citric acid was obtained

0.48 0.46 0.48

from the Physiology Department of BMSI, JPMC,

Karachi. Flow rate (ml/min) of saliva was deter- 0.51 0.46 0.46

mined by allowing the saliva to flow into a gradu- 0.49 0.45 0.48

ated tube. The data was statistically analyzed by

Student’s t test.11,12 Controls Controls Controls

(res) (nic) (cit)

RESULTS 0.45 0.6 0.89

The resting (basal) salivary flow rates in both 0.44 0.67 0.8

the groups showed nearly a steady level during

10 minutes of sampling in the range of 0.46±0.05 0.44 0.72 0.74

to 0.51±0.05 ml/min in smokers and 0.43±0.05 0.44 0.64 0.66

to 0.49±0.05 ml/min in non-smokers (controls).

After application of crude nicotine solution (50 ml 0.43 0.59 0.58

of 1% v/v) to the tips of their tongues, a gradual 0.46 0.51 0.47

increase in the flow rate was seen which reached

0.43 0.44 0.45

its peak level (0.71±0.05 ml/min) within 3.0 min-

utes and subsided to its resting level (0.46±0.05 0.49 0.44 0.43

ml/min) within the next 4.0 minutes in smokers.

0.47 0.41 0.43

However, in controls the maximum level (0.72±0.04

ml/min) was reached in 3.0 minutes and declined 0.45 0.42 0.43

to its basal level (0.0.41±0.04 ml/min) in the next

Each figure represents ml/minute (res = resting

6.0 minutes.

condition, nic = after stimulation with nicotine

Following stimulation with citric acid solu- solution, cit = after stimulation with citric acid

tion (50 ml of 1% w/v), an abrupt rise in the flow solution).

rate was observed which reached its peak level

(0.85±0.06 ml/min) within the 1st minute and then increased to 0.54±0.04 ml/min (22.73%) in con-

gradually came down nearly to its resting level trol and to 0.55±0.05 ml/min (12.25%) in smok-

(0.46±0.05 ml/min) within the next 8.0 minutes. In ers. However, the increase was statistically signifi-

controls similar observations were noted where cant (P<0.05) in controls only but when the in-

the peak level (0.89±0.05 ml/min) reached within crease was compared with each other, it was not

1st minute and the basal level (0.0.43±0.05 ml/min) significant.

reached within the next 7.0 minutes.

Following stimulation with citric acid, the

Under resting conditions the mean salivary mean flow rates further increased to 0.59±0.05

flow rate of controls (0.44±0.04ml/min) and smok- ml/min (34.09%) in controls and 0.60±0.05 ml/min

ers (0.49±0.05 ml/min) did not show any great (22.45%) in smokers. The increase was not statis-

variation from each other and no statistically sig- tically significant in smokers but significant

nificant difference was observed when the smok- (P<0.05) in controls. However, the increase

ers were compared with controls. After stimula- was not significant when compared with each

tion with nicotine, the mean salivary flow rates were other.

Gomal Journal of Medical Sciences July-December 2010, Vol. 8, No. 2 222

Effect of smoking on salivary flow rate

application 7. It is suggested that oral mucosal

wetness and minor salivary gland secretion could

be influenced by various factors differently accord-

ing to mucosal sites.17 Moreover, temperature of

stimulating substances also affects salivary secre-

tion because the stimuli in the form of ice were the

most effective and liquids at 370C were least effec-

tive in stimulating salivary flow.18

It was noted that buffering response in smok-

ers in response to drinking acidic carbonated bev-

erages is 20% lower than in non-smokers. On this

basis an inactivation of the taste receptors by nico-

tine was suggested as an explanation for this de-

pression of the salivary reflex.19 Although we have

not studied the buffering response of saliva in our

study, yet we were unable to find any significant

difference in the salivary response to stimulating

substances between smokers and non-smokers.

It seems, therefore, somewhat unreasonable to

suggest an inactivation of the taste receptors

merely on the basis of lowered buffering response

of saliva in smokers11. Moreover it was also found

that the pH of stimulated whole saliva, in both

sexes, was lower in smokers than non-smokers4.

In our opinion, this lowered buffering response to

acidic carbonated beverages might be due to this

acidic pH in these individuals. Similarly no statisti-

cally significant different was observed for either

Fig 1: Comparison of salivary flow rates of smok- over all taste sensitivity or for the specific taste

ers and non-smokers as controls before primaries between smokers and non-smokers.20

and after stimulation with nicotine and cit- We found that lingual apex application of

ric acid solutions; (res = resting condi- nicotine and citric acid was associated with a rise

tion, nic = after stimulation with nicotine in salivary secretion rate but the salivation response

solution, cit = after stimulation with citric to citric acid was abrupt and more pronounced

acid solution). as compared to nicotine proving that citric acid is

more potent and quicker in its action.

DISCUSSION The effect of nicotine on the taste nerve ap-

paratus appears to be initial stimulation followed

The salivary secretion is a complex process by depression.5 In the present and in our earlier

and its flow and composition vary greatly under study11 the initial increase in the flow of saliva fol-

different conditions.12 In a study it was thought lowing stimulation by both nicotine and citric acid

that saliva collected routinely in the laboratory as and then gradual decline towards its basal level

“resting” saliva is in fact stimulated or activated also gives similar impression but before establish-

secretion and gross variation in the rate of its se- ing such an opinion it must be borne in mind that

cretion are due to fluctuation in intensity and fre- increased flow of saliva also gradually washes away

quency of internal stimulation. It is said that the the stimulating substances. It has recently been

secretion of saliva from the salivary glands is gen- revealed that taste function presents significant

erally elicited only in response to stimulation of resistance to smoking.21

the autonomic innervations to the glands or in re-

sponse to drugs that mimic the actions of auto- CONCLUSION

nomic innervations.13-15 was also found that differ-

ent chemicals stimulate the salivary secretion dif- In view of the present experimental work it is

ferently.16 It has been observed that the pattern of concluded that smoking does not adversely af-

taste sensations and salivary secretion in man fol- fect salivary reflex and salivary secretion.

lowing application of compounds, like nicotine

and citric acid, to the tongue, which activate lin- REFERENCES

gual sensory neurons, differ not only between the 1. Levinson S A, MacFate RB. Clinical laboratory

agents used but also between different sites of diagnosis. Lea & Feibiger. 1961:129-40.

Gomal Journal of Medical Sciences July-December 2010, Vol. 8, No. 2 223

Ghulam Jillani Khan, et al.

2. Khan GJ, Mahmood R. Haq IU, Din SU. Secre- and salivary secretion. J Ayub Med Coll 2003;

tion of total solids (solutes) in the saliva of long- 15: 37-9.

term tobacco users. J Ayub Med Coll 2008; 20:

20-2. 14. Schneyer LH, Pigman W, Hanana L, Gilmore RW.

Rate of flow of human parotid, sublingual and

3. Standring S, Ellis H, Healy JC, Johnson D, Will- sub-maxillary secretions during sleep. J Dent

iams A. Gray’s Anatomy, The Anatomical Basis Res 1956; 35: 109-14.

of Clinical Practice. 39thedn. Elsevier Churchill

Livingstone. 2005: p. 581-608. 15. Schneyer LH, Young JA, Schneyer CA. Salivary

secretion of electrolytes. Physiol Rev; 1972; 52:

4. Guyton AC, Hall JE. Textbook of Medical Physi- 720-77.

ology. 11thedn. Saunders An Imprint of Elsevier.

2006: 791-807. 16. Jones CJ, Wilson SM. The effect of autonomic

agonists and nerve stimulation on protein se-

5. Uematsu T, Yamaoka M, Matsuura T, Doto R, cretion from the rat submandibular gland. J

Hotomi H, Yamada A, Hasumi-Nakayama Y, Physiol 1985; 385: 65-73.

Kayamoto D. P-glycoportien expression in hu-

man major and minor salivary glands. Arch Oral 17. Won S, Kho H, Kim Y, Chung S, Lee S. The effect

Biol 2001; 46: 521-7. of age on taste sensitivity. Arch Oral Biol 2001;

46: 619-24

6. Larson PS, Haag HB, Silvette H. Tobacco, Ex-

perimental and Clinical Studies. The Williams 18. Dawes C, O’Connor AM, Aspen JM. The

and Wilkins Company. Baltimore. 1961. effect on human salivary flow rate of the

temperature of a gustatory stimulus. 2000; 45:

7. Heintz U. Secretion rate, buffer effect and num- 957-61.

ber of lactobacilli and streptococcus mutans of

whole saliva of cigarette smokers and non-smok- 19. Oster RH, Prouth LM, Shipley ER, Pallack BR,

ers. Scand J Dent Res 1984; 1: 294-301. Bradley JE. Human buffering rate measured in

situ in response to an acid stimulus found in

8. Parvinen T. Stimulated salivary flow rate, pH and some common beverages. J Appl Physil. 1953-

lactobacillus and yeast concentrations in non- 1954; 6: 348-54.

smokers and smokers. Scand J Dent Res 1984;

92: 315-8. 20. Cooper RM, Bilash I, Zubek JP. The effect of

age on taste sensitivity. J Gerontol 1959; 14:

9. Engstom MD, Fredholman BB, Larsson O, 56-8.

Lundberg JM, Saria A. Autonomic mechanisms

underlying capsaicin induced oral sensations 21. Konstantinidis I, Chatziavramidis A, Printza A,

and salivation in man. J Physiol 1986; 373: Metaxas S, Constantinidis J. Effects of smoking

87-96. on taste: assessment with contact endoscopy

and taste strips. Laryngoscope 2010; 120:

10. Pavia DL, Lampman GM, Kriz Jr GS. In: Intro- 1958-63.

duction to Organic Laboratory Techniques, A

Contemporary Approach. Philadelphia W B

Saunders Company. 1976: p. 46-54.

Corresponding author:

11. Chaudary SM. Introduction to Statistical Theory

(Part 2). Ilmi Kitab Khana Lahore. 1985: Dr. Ghulam Jillani Khan

p. 167-206.

Assoc. Professor

12. Ganong WF. Review of Medical Physiology. Department of Physiology

22 ndedn. McGraw Hill Companies. 2005: p.

811-4. Khyber Medical College

Peshawar, Pakistan

13. Khan GJ, Mahmood R. Haq IU, Din SU. Effects

of long-term use of tobacco on taste receptors E-mail: banisy_no1@yahoo.com

Gomal Journal of Medical Sciences July-December 2010, Vol. 8, No. 2 224

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- BIOCHEM LAB - Enzymatic Activity of Salivary AmylaseDocument6 pagesBIOCHEM LAB - Enzymatic Activity of Salivary AmylaseIsmael Cortez100% (2)

- General - GITDocument90 pagesGeneral - GITAbdallah GamalNo ratings yet

- 11 Status Epilepticus PDFDocument6 pages11 Status Epilepticus PDFAgnes NiyNo ratings yet

- Faktor Depresi Pada Ibu HamilDocument11 pagesFaktor Depresi Pada Ibu HamilYodi WijayaNo ratings yet

- Chronic Rhinosinusitis 2012Document305 pagesChronic Rhinosinusitis 2012Sorina StoianNo ratings yet

- LMWHDocument17 pagesLMWHAhmad FauzanNo ratings yet

- Faktor Depresi Pada Ibu HamilDocument11 pagesFaktor Depresi Pada Ibu HamilYodi WijayaNo ratings yet

- ScrotalDocument7 pagesScrotalYodi WijayaNo ratings yet

- CHT Hfa Boys Z 2 5Document1 pageCHT Hfa Boys Z 2 5Sunu RachmatNo ratings yet

- Neuro - Cluster HeadacheDocument16 pagesNeuro - Cluster HeadacheYodi WijayaNo ratings yet

- CCH and The Pituitary GlandDocument4 pagesCCH and The Pituitary GlandYodi WijayaNo ratings yet

- Kesehatan Gigi Dan Mulut Pada PerokokDocument8 pagesKesehatan Gigi Dan Mulut Pada PerokokYodi WijayaNo ratings yet

- G1a111081 Artikel PDFDocument8 pagesG1a111081 Artikel PDFYodi WijayaNo ratings yet

- Kesehatan Gigi Dan Mulut Pada PerokokDocument8 pagesKesehatan Gigi Dan Mulut Pada PerokokYodi WijayaNo ratings yet

- Mouth Tongue and Salivary GlandsDocument52 pagesMouth Tongue and Salivary GlandsIrfan FalahNo ratings yet

- Study of Animal TypesDocument4 pagesStudy of Animal TypesAnonymous X4QS89Um8wNo ratings yet

- 922 1607 1 SM PDFDocument6 pages922 1607 1 SM PDFdeboraNo ratings yet

- Antimicrobial Defense Systems in Saliva: Wim Van 'T Hof Enno C.I. Veerman Arie V. Nieuw Amerongen Antoon J.M. LigtenbergDocument12 pagesAntimicrobial Defense Systems in Saliva: Wim Van 'T Hof Enno C.I. Veerman Arie V. Nieuw Amerongen Antoon J.M. Ligtenbergjulist.tianNo ratings yet

- Acinii SalivariDocument5 pagesAcinii SalivariIo DobriNo ratings yet

- J-CAPS-01 (SC+MATHS) Class X (17th To 23rd Apr 2020) by AAKASH InstituteDocument5 pagesJ-CAPS-01 (SC+MATHS) Class X (17th To 23rd Apr 2020) by AAKASH InstitutemuscularindianNo ratings yet

- List of Daycare Procedures: Microsurgical Operations On The Middle EarDocument4 pagesList of Daycare Procedures: Microsurgical Operations On The Middle EarAjay TiwariNo ratings yet

- 2011 - Saliva As A Tool For Monitoring Steroid, Peptide and Immune Markers - Papacosta - JSciMedSportDocument11 pages2011 - Saliva As A Tool For Monitoring Steroid, Peptide and Immune Markers - Papacosta - JSciMedSportBilingual Physical Education ClassesNo ratings yet

- Digestive System (Final)Document164 pagesDigestive System (Final)aubrey alcantaraNo ratings yet

- O Level Biology Notes MapurangaDocument95 pagesO Level Biology Notes Mapurangapeterchiyanja100% (2)

- KL MCQ 2Document2 pagesKL MCQ 2majaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0196070923000819 MainDocument6 pages1 s2.0 S0196070923000819 MainRALF KEVIN PIANONo ratings yet

- Physiology Stomatognathic SystemDocument19 pagesPhysiology Stomatognathic SystemDan 04No ratings yet

- Surgical CP ParotidDocument43 pagesSurgical CP ParotidValarmathiNo ratings yet

- SALIVADocument68 pagesSALIVANimmi RenjithNo ratings yet

- Digestion New BioHackDocument10 pagesDigestion New BioHackManav SinghNo ratings yet

- Perbedaan Antara PH Saliva Dan Aktivitas Enzim Amilase Mahasiswa Yang Merokok Dengan Mahasiswa Yang Tidak MerokokDocument9 pagesPerbedaan Antara PH Saliva Dan Aktivitas Enzim Amilase Mahasiswa Yang Merokok Dengan Mahasiswa Yang Tidak MerokokWinda AlzamoriNo ratings yet

- Salivary Digestion PartDocument3 pagesSalivary Digestion PartDham DoñosNo ratings yet

- Physiology, Gastrointestinal Article - StatPearls PDFDocument5 pagesPhysiology, Gastrointestinal Article - StatPearls PDFThanh TrúcNo ratings yet

- BASICS of ORAL PHYSIOLOGY (Part 1)Document171 pagesBASICS of ORAL PHYSIOLOGY (Part 1)Balarabe EL-HussainNo ratings yet

- Farko Cerna UTS + TugasDocument357 pagesFarko Cerna UTS + TugasAnnisa N RahmayantiNo ratings yet

- Pengaruh Pajanan Radiasi Sinar-X Dari Radiografi Panoramik Terhadap PH SalivaDocument6 pagesPengaruh Pajanan Radiasi Sinar-X Dari Radiografi Panoramik Terhadap PH SalivamutiyasNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry of Saliva: DR: Abou Sree EllethyDocument16 pagesBiochemistry of Saliva: DR: Abou Sree Ellethylethy2000No ratings yet

- Chapter 24 (Digestive System) Chapter 24 (Digestive System)Document30 pagesChapter 24 (Digestive System) Chapter 24 (Digestive System)Pranali BasuNo ratings yet

- Giant Dental Calculus: A Rare Case Report and ReviewDocument3 pagesGiant Dental Calculus: A Rare Case Report and ReviewKiyRizkikaNo ratings yet

- Tests - English - 2014 10.04.14Document45 pagesTests - English - 2014 10.04.14Parfeni DumitruNo ratings yet

- Superfical Parotidectomy Is Contraindicated in Patients With Sialectasis BecauseDocument24 pagesSuperfical Parotidectomy Is Contraindicated in Patients With Sialectasis BecauseAbouzr Mohammed Elsaid100% (1)

- GIT Physio D&R AgamDocument67 pagesGIT Physio D&R Agamvisweswar030406No ratings yet