Professional Documents

Culture Documents

ABECEDAR

Uploaded by

Diana Ioana ȘtefănescuOriginal Description:

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

ABECEDAR

Uploaded by

Diana Ioana ȘtefănescuCopyright:

Available Formats

ABECEDAR

Following the Treaty of Bucharest in 1913, the southern part of the so-called historic region

of Macedonia was annexed to the Kingdom of Greece, with Bulgarians making up a debated portion

of the overall population at the time, with estimates ranging from 10%[2] to a 30% plurality[3]. Under

the 1920 Treaty of Sèvres, Greece opened schools for minority-language children, and in September

1924 Greece agreed to a protocol with Bulgaria to place its Slavic-speaking minority under the

protection of the League of Nations as Bulgarians. However, the Greek parliament refused to ratify

the protocol due to objections from Serbia, considering the Slavic-speakers to be Serbs rather

than Bulgarians, and from Greeks who considered the Slavic-speakers to be Slavicized Greeks rather

than ethnic Slavs.[4] Vasilis Dendramis, the Greek representative in the League of the Nations, stated

that Macedonian Slav language was neither Bulgarian, nor Serbian, but an independent language.[1]

The Greek government went ahead with the publication in May 1925 of the Abecedar, described by

contemporary Greek writers as a primer for "the children of Slav speakers in Greece ... printed in the

Latin script and compiled in the Macedonian dialect."[5] The book was commissioned by the

Department for the Education of Foreign-Speakers in the Greek Ministry of Education. It was

submitted by the Greek government to the League of Nations to support its assertion that it fulfilled

obligations towards the Slavic-speaking minority.[4]

The book's publication sparked controversy in Greek Macedonia, along with Bulgaria and Serbia. The

Bulgarians and Serbs objected to the book being printed in Latin alphabet, despite the Bulgarian and

Serbian languages being written predominately in the Cyrillic alphabet. The Bulgarian representative

to the League of Nations criticized it as "incomprehensible."[6] Although some books reached villages

in Greek Macedonia, it was never used in their schools. In one village, threats by local police led to

residents throwing their copies into a lake.[4] In January 1926, the region of Florina saw extensive

protests by Greek and pro-Greek Slavic speakers campaigning against the primer's publication,

demanding the government change their policies on minority education.[7]

Professor Loring Danforth argues the Abecedar was printed in the Latin alphabet "precisely to ensure

[sic] that it would be rejected by all parties concerned" so "it would not contribute to the

development of ties between the Slavic-speaking people of northern Greece and either Serbia or

Bulgaria." The Republic of North Macedonia argues it demonstrated a separate Macedonian

language and people existed in northern Greece in 1925, and the Greek government recognized it as

such.[4] Bulgarian authors indicate that this textbook was printed in order to mislead the

international organizations that the educational rights of the Bulgarians in Greece are respected – in

the moment when the Council of the League of Nations treated the question about protection of the

Bulgarian minority in Greece.[8]

According to Victor Roudometof, the incident led to significant change in the Greek government's

stance toward Slavic-speaking citizens. Henceforth, they were deemed to be neither Serbs nor

Bulgarians, and their difference was regarded as solely linguistic, not ethnic or political.[7]

The first scientific review of Abecedar was made in 1925 by professor Lyubomir Miletich who treated

this schoolbook as an attempt to create new, Latin, alphabet for Bulgarians in Greek Macedonia.[9]

You might also like

- Aegean Macedonia After The Balkan WarsDocument9 pagesAegean Macedonia After The Balkan WarsBasil ChulevNo ratings yet

- The Hellenicity of The Linguistic OtherDocument11 pagesThe Hellenicity of The Linguistic OtherYluvarNo ratings yet

- Yugoslav Communism and The Macedonian QuestionDocument24 pagesYugoslav Communism and The Macedonian QuestionMaketo100% (2)

- Greek-Albanian Relations The Past The Present andDocument12 pagesGreek-Albanian Relations The Past The Present andnotisNo ratings yet

- OKEY - Language and NationalityDocument24 pagesOKEY - Language and NationalitysancicNo ratings yet

- Macedonia 1918-1940 BF OfficeDocument17 pagesMacedonia 1918-1940 BF OfficeIgorNo ratings yet

- Michailidis AbecedarDocument10 pagesMichailidis Abecedarapi-235372025No ratings yet

- A British Officer's Report, 1944Document31 pagesA British Officer's Report, 1944Dejan BojkoskiNo ratings yet

- British Foreign Office and Macedonian National Identity (1918-1941) by Andrew RossosDocument20 pagesBritish Foreign Office and Macedonian National Identity (1918-1941) by Andrew RossosBasil ChulevNo ratings yet

- Macedonian Language and Nationalism During The Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.Document16 pagesMacedonian Language and Nationalism During The Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries.Документи за Македонската историјаNo ratings yet

- The Macedonian Question Djoko SlijepcevicDocument269 pagesThe Macedonian Question Djoko Slijepcevicvuk300100% (2)

- Tinatin Margalitadze - English-Georgian PDFDocument21 pagesTinatin Margalitadze - English-Georgian PDFMonahul Hristofor Mocanu0% (1)

- ΜΙΧΑΗΛΙΔΗΣ ΙΑΚΩΒΟΣ - ABECEDARDocument10 pagesΜΙΧΑΗΛΙΔΗΣ ΙΑΚΩΒΟΣ - ABECEDARIoannis G. MavrosNo ratings yet

- ALL S1L1 020712 Bpod101Document5 pagesALL S1L1 020712 Bpod101YaniNo ratings yet

- Ethnicity of Medieval EpirusDocument10 pagesEthnicity of Medieval EpirusIDEMNo ratings yet

- Victor - A - Friedman - Macedonian - Language - and Nationalism During The XIX and Early XX CenturyDocument18 pagesVictor - A - Friedman - Macedonian - Language - and Nationalism During The XIX and Early XX CenturyIreneoNo ratings yet

- Grigor Parlichev's Life and Identification as a WriterDocument3 pagesGrigor Parlichev's Life and Identification as a WritermarijaNo ratings yet

- Robert Browning's Guide to the Development of Greek LanguageDocument164 pagesRobert Browning's Guide to the Development of Greek LanguageNatalia100% (2)

- De Rapper 2001aDocument8 pagesDe Rapper 2001aSaša GrujićNo ratings yet

- Bulgarian-Albanian Political Relations 1908-1915Document14 pagesBulgarian-Albanian Political Relations 1908-1915OliverAndovski100% (1)

- Greater Albania: The nationalist concept seeking to unite Albanian-majority landsDocument15 pagesGreater Albania: The nationalist concept seeking to unite Albanian-majority landsKDNo ratings yet

- Бугарска историографијаDocument8 pagesБугарска историографијаandrej08No ratings yet

- Jewish Languages: Jews and JudaismDocument7 pagesJewish Languages: Jews and Judaismdzimmer6No ratings yet

- FYROM's Dispute With Greece Revisited - Demetrius Andreas FloudasDocument29 pagesFYROM's Dispute With Greece Revisited - Demetrius Andreas FloudasMarsyas PeriandrouNo ratings yet

- Tomasz Kamusella: The Idea of A Kosovan Language in YugoslaviaDocument21 pagesTomasz Kamusella: The Idea of A Kosovan Language in YugoslaviaHistorica VariaNo ratings yet

- Balkanologie 2342 PDFDocument21 pagesBalkanologie 2342 PDFPontus LindgrenNo ratings yet

- 1913 Treaty of Bucharest (By Marcus A. Templar)Document6 pages1913 Treaty of Bucharest (By Marcus A. Templar)Macedonia - The Authentic TruthNo ratings yet

- Christian KoineDocument2 pagesChristian KoineΙωάννα ΞενάκηNo ratings yet

- Final Assignment RLTDocument11 pagesFinal Assignment RLTAyunda Eka PutriNo ratings yet

- Albanian Language and Literature SurveyDocument54 pagesAlbanian Language and Literature SurveyObjctiveseaNo ratings yet

- Macedonians: A Contested People in a Contested RegionDocument75 pagesMacedonians: A Contested People in a Contested Regiontzababagita936No ratings yet

- Aram, 15 (2003), 269-274: TH TH 1Document6 pagesAram, 15 (2003), 269-274: TH TH 1Arcadie BodaleNo ratings yet

- Pelasgic Encounters in The Greek Albanian Borderland de Rapper Gilles 2009Document16 pagesPelasgic Encounters in The Greek Albanian Borderland de Rapper Gilles 2009Bida bidaNo ratings yet

- Jewish Koine PDFDocument4 pagesJewish Koine PDFSebastian GhermanNo ratings yet

- Lexical Elements of Slavic Origin in Judezmo On South Slavic Territory, 16-19th Centuries: Uriel Weinreich and The History of Contact LinguisticsDocument36 pagesLexical Elements of Slavic Origin in Judezmo On South Slavic Territory, 16-19th Centuries: Uriel Weinreich and The History of Contact LinguisticsHalil İbrahim ŞimşekNo ratings yet

- The Language Policy in Yugoslavia - The Implications of The Declaration On The Name and Status of The Croatian Literary LanguageDocument10 pagesThe Language Policy in Yugoslavia - The Implications of The Declaration On The Name and Status of The Croatian Literary LanguageMatko GalićNo ratings yet

- Kabyle in Arabic Script: A History Without Standardisation: Lameen SouagDocument24 pagesKabyle in Arabic Script: A History Without Standardisation: Lameen Souagzaid ijoudNo ratings yet

- CroatiaDocument9 pagesCroatiasebastian torreNo ratings yet

- The Macedonian QuestionDocument21 pagesThe Macedonian Questionahc13No ratings yet

- File 33676Document267 pagesFile 33676mastermayemNo ratings yet

- Ancient Macedonian Language According To Modern SourcesDocument8 pagesAncient Macedonian Language According To Modern SourcesHistory-of-Macedonia.com100% (1)

- Introduction "Ladino in Print" - Sarah Abrevaya SteinDocument9 pagesIntroduction "Ladino in Print" - Sarah Abrevaya SteinCurso De Ladino Djudeo-Espanyol100% (1)

- Asia LiteratureDocument3 pagesAsia Literaturemoveena abdullahNo ratings yet

- Bajram Doka.: "Illyrian Languages in Albanian Dialects"Document10 pagesBajram Doka.: "Illyrian Languages in Albanian Dialects"Andi PilinciNo ratings yet

- The Greek Language of Cultural GenocideDocument10 pagesThe Greek Language of Cultural GenocideVictor BivellNo ratings yet

- The Konikovo Gospel and the Development of Macedonian IdentityDocument8 pagesThe Konikovo Gospel and the Development of Macedonian IdentityBakarovPetreNo ratings yet

- Language Politics in The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia The Crisis Over The Future of SerbianDocument16 pagesLanguage Politics in The Federal Republic of Yugoslavia The Crisis Over The Future of SerbianBenjamin SmithNo ratings yet

- Tabidze, Manana - Sociolinguistic Aspects of The Development of Georgian (1999)Document10 pagesTabidze, Manana - Sociolinguistic Aspects of The Development of Georgian (1999)Dominik K. CagaraNo ratings yet

- A 2012 Bar TragedyDocument12 pagesA 2012 Bar Tragedymicky_haxNo ratings yet

- De Felipe Berber Language Thorugh Arab EyesDocument20 pagesDe Felipe Berber Language Thorugh Arab EyesMiguelNo ratings yet

- Microsoft Word - Trudgill For Agder Course IIDocument26 pagesMicrosoft Word - Trudgill For Agder Course IIsapatoriaNo ratings yet

- Whose Language? Exploring The Attitudes of Bulgaria's Media Elite Toward Macedonia's Linguistic Self-IdentificationDocument22 pagesWhose Language? Exploring The Attitudes of Bulgaria's Media Elite Toward Macedonia's Linguistic Self-IdentificationVMRONo ratings yet

- Who The Macedonians Really AreDocument4 pagesWho The Macedonians Really AreМиле В. ВасиљевићNo ratings yet

- Bulgarian Sham or Greek FoolishnessDocument3 pagesBulgarian Sham or Greek FoolishnessMcDusan100% (1)

- The Yiddish Historians and the Struggle for a Jewish History of the HolocaustFrom EverandThe Yiddish Historians and the Struggle for a Jewish History of the HolocaustNo ratings yet

- Historical View of the Languages and Literature of the Slavic Nations With a Sketch of Their Popular PoetryFrom EverandHistorical View of the Languages and Literature of the Slavic Nations With a Sketch of Their Popular PoetryNo ratings yet

- If You Can't Say Anything Nice, Say It In Yiddish: The Book Of Yiddish Insults And CursesFrom EverandIf You Can't Say Anything Nice, Say It In Yiddish: The Book Of Yiddish Insults And CursesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (7)

- Easter 3Document1 pageEaster 3Diana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Easter 4Document1 pageEaster 4Diana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Easter 1Document1 pageEaster 1Diana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Christmas 1Document1 pageChristmas 1Diana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Christmas 4Document1 pageChristmas 4Diana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Baby Cards 1Document1 pageBaby Cards 1Diana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Baby Cards 2Document1 pageBaby Cards 2Diana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Christmas 2Document1 pageChristmas 2Diana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- COCODocument1 pageCOCODiana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Baby CardsDocument1 pageBaby CardsDiana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Use. Typewriters Tend To Collect Dust Which Over Time Will CreateDocument2 pagesUse. Typewriters Tend To Collect Dust Which Over Time Will CreateDiana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Diana Diana DianaDocument1 pageDiana Diana DianaDiana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- DianaDocument1 pageDianaDiana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- MarilinDocument1 pageMarilinDiana Ioana ȘtefănescuNo ratings yet

- Data Jamaah Lunas PerkecamatanDocument148 pagesData Jamaah Lunas Perkecamatannrl firahNo ratings yet

- WritingDocument6 pagesWritingHải Yến NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Final Pre-Nomination On Kathmandu University, MBBS Scholarship, 2076 Pre - Nomination of All GroupsDocument2 pagesFinal Pre-Nomination On Kathmandu University, MBBS Scholarship, 2076 Pre - Nomination of All GroupsRohit Kumar SahNo ratings yet

- 21STDocument13 pages21STCristel CombalicerNo ratings yet

- China Breaking IndiaDocument11 pagesChina Breaking IndiacbcnnNo ratings yet

- A Little Happiness - Hebe Tien PDFDocument4 pagesA Little Happiness - Hebe Tien PDFpr1sNo ratings yet

- Seerat Imam Ahmad Raza BarelviDocument69 pagesSeerat Imam Ahmad Raza BarelvimcqsmastermindNo ratings yet

- Appreciation Letter Aug 18Document8 pagesAppreciation Letter Aug 18sysfqnrNo ratings yet

- Military Operations in The Era of Prophet Mohammed (Phuh)Document10 pagesMilitary Operations in The Era of Prophet Mohammed (Phuh)Abdul HameedNo ratings yet

- Schools and Principals ListDocument8 pagesSchools and Principals ListRadsreads80% (5)

- The Interpreter - FactsDocument5 pagesThe Interpreter - FactsFelipe GuevaraNo ratings yet

- 188 NHẬN ĐỊNH VĂN HỌCDocument14 pages188 NHẬN ĐỊNH VĂN HỌCBạch Thỏ ĐậuNo ratings yet

- The Tithe of YHWHDocument23 pagesThe Tithe of YHWHblouvalkNo ratings yet

- ANGELS, CHERUBIM AND SERAPHIMDocument8 pagesANGELS, CHERUBIM AND SERAPHIMGabriel Inya-Agha100% (2)

- 4929 21770 1 PBDocument22 pages4929 21770 1 PBriqi2412No ratings yet

- The Curse of Canaan by Eustace MullinsDocument160 pagesThe Curse of Canaan by Eustace Mullinsdagcity89% (9)

- Great Thoughts From Latin AuthorsDocument678 pagesGreat Thoughts From Latin Authorsjamuleti1263No ratings yet

- MA - History of The Mabhudu-Tembe - RJ KloppersDocument120 pagesMA - History of The Mabhudu-Tembe - RJ Kloppersapi-3750042100% (5)

- Laboring in The Fields of The LordDocument5 pagesLaboring in The Fields of The LordRTorres899No ratings yet

- Lloyd School of Law, Greater Noida: Batch: 2022-25 II Sem S.No. Enrollment No Roll No NameDocument12 pagesLloyd School of Law, Greater Noida: Batch: 2022-25 II Sem S.No. Enrollment No Roll No Namejay.kishanNo ratings yet

- The Great Apostasy - Mattew 24Document1 pageThe Great Apostasy - Mattew 24Second ComingNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument17 pagesUntitledSEKOLAH MENENGAH KEBANGSAAN BANDAR KOTA TINGGI MoeNo ratings yet

- Integrated Vocabulary of Mobilian JargonDocument107 pagesIntegrated Vocabulary of Mobilian JargonJaviera VillarroelNo ratings yet

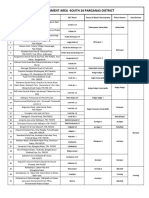

- Containment Area - South 24 Parganas DistrictDocument2 pagesContainment Area - South 24 Parganas DistrictShraddha ChowdhuryNo ratings yet

- The Sabbath: Easy Reading Edition September 6-12Document7 pagesThe Sabbath: Easy Reading Edition September 6-12Ritchie FamarinNo ratings yet

- This Is Peru!: Activity 4: A Good Classmate Is A Good CitizenDocument4 pagesThis Is Peru!: Activity 4: A Good Classmate Is A Good CitizenAnderson Antonio Carrasco GarcíaNo ratings yet

- (Math) Program Peningkatan Akademik SPM 2022Document2 pages(Math) Program Peningkatan Akademik SPM 2022MOHD NORFERZLY BIN MOHAMED MoeNo ratings yet

- Result of AvSec Instructor Course Batch IDocument1 pageResult of AvSec Instructor Course Batch Iravi rahulNo ratings yet

- Using Adjectives to Express EmotionsDocument13 pagesUsing Adjectives to Express EmotionsJudy Ann De VeraNo ratings yet

- Bhagavad Gita Marathi - Adhyay 12Document10 pagesBhagavad Gita Marathi - Adhyay 12aekay100% (3)