Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cultivation of Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus PDF

Uploaded by

awal ismailOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cultivation of Oyster Mushroom Pleurotus PDF

Uploaded by

awal ismailCopyright:

Available Formats

Cey. J. Sci. (Bio. Sci.

) 37 (2): 177-182, 2008

CULTIVATION OF OYSTER MUSHROOM (PLEUROTUS

OSTREATUS) ON SAWDUST

L. Pathmashini 1*, V. Arulnandhy 2 and R.S. Wilson Wijeratnam 3

1

Department of Agricultural Engineering, Faculty of Agriculture, Eastern University, Sri Lanka

2

Department of Agricultural Biology, Faculty of Agriculture, Eastern University, Sri Lanka

3

Food Technology Division, Industrial Technology Institute (ITI), Colombo 7, Sri Lanka

Accepted 25 November 2008

ABSTRACT

A study was conducted to examine the effect of different types of spawns on oyster mushroom

(Pleurotus ostreatus) production using sawdust. Locally available grains of kurakkan (Eleusine coracana),

maize (broken) (Zea mays), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), and paddy (Oryza sativa) were used for spawn

production. Sawdust spawned with different types P. ostreatus spawns were examined for spawn running

(mycelia development), pinhead formation and fruit body formation, mean yield, and biological efficiency.

The experiment was setup as a complete randomized design with three replicates. The kurakkan spawn

produced an acceleration of spawn running, pinhead formation, fruit body formation and increased yield,

compared with other types of spawn viz.; maize, sorghum, and paddy. The fastest spawn running of 21 ± 1

days, pinhead formation of 35 ± 1 days, highest mean yield of 55.37 ± 0.67 g and maximum fresh

mushroom yield percentage of 30.76 ± 0.01 were realized for kurakkan spawn.

Key words: Eleusine coracana, Pleurotus ostreatus, Sorghum bicolor, Oryza sativa, Zea mays, spawn

INTRODUCTION 2000). Among the reasons for the quick

acceptance of mushroom is its nutritive content.

Oyster mushroom (Pleurotus spp.) Mushrooms are eaten as meat substitutes and

cultivation has increased tremendously flavouring. In general edible mushrooms are low

throughout the world during the last few decades in fat and calories, rich in vitamin B and C,

(Chang, 1999; Royse, 2002). Oyster mushroom contain more protein than any other food of

accounted for 14.2 % of the total world plant origin and are also a good source of

production of edible mushroom in 1997 (Chang, mineral nutrients (Bahl, 1998).

1999). Oyster mushroom cultivation can play an

important role in managing organic wastes Currently, high biofuel prices have caused an

whose disposal has become a problem (Das and increase in food prices and food scarcity in many

Mukherjee, 2007). Oyster mushroom can be countries (World Bank, 2008). To alleviate

cultivated in any type of ligno cellulose material hunger and malnutrition in a world of rising food

like straw, sawdust, rice hull, etc. Hami (1990) prices, cultivation of mushrooms is a very

studied the oyster mushroom cultivation on reliable and profitable option.

sawdust of different woods and found that

P.ostreatus gave the maximum yield. Presently The objectives of this study were to evaluate

sawdust is commonly used and is the preferred selected grain media for spawn production and

medium at commercial scale. Hami (1990) find out the most suitable media for spawn

reported that P.ostreatus gave maximum production.

biological efficiency on sawdust. Of the sawdust

types, softwood sawdust like mango and cashew

are known to be more suitable than hardwood MATERIALS AND METHODS

sawdust.

Location

Malnutrition is a problem in developing third The spawn production was carried out at the

world countries. Mushrooms with their flavour, Industrial Technology Institute (ITI), Colombo.

texture, nutritional value and high productivity Experiments were carried out in a pre built

per unit area have been identified as an excellent mushroom hut at the Faculty of Agriculture,

food source to alleviate malnutrition in Eastern University.

developing countries (Eswaran and Ramabadran,

__________________________________________

*Corresponding author’s email: littlepathu@yahoo.com

Pathmashini et al. 178

Stock pure cultures in the growing house. The days required for the

Stock pure culture of P. ostreatus obtained completion of spawn running in the substrate

from Industrial Technology Institute (ITI), bag were recorded. Days for pinhead formation,

Colombo was maintained on Potato Dextrose fruit body (flush) formation and for harvest was

Agar (PDA). recorded.

Spawn production Mushroom yield

The grains, kurakkan, maize, sorghum and Total mushroom yield (five flushes) was

paddy were cleaned manually to remove inert expressed as accumulated fresh weight of

matter, stubble and debris. The cleaned grains mushrooms and as the accumulated biological

were soaked in 0.5% CuSO4 for 10 min and the efficiency (BE), i.e. accumulated fresh weight of

soaked grains were thoroughly washed and mushrooms expressed on the basis of dry weight

soaked in tap water for 2 hours. Thereafter, the of initial substrate.

soaked grains were drained and the excess water

removed and the following additives added. Experimental design

Rice bran at the rate of 10%, chalk (CaCO3) at In the experiments complete randomized

the rate of 2%, and epsom (MgSO4) at the rate of design with three replicates and four types of

0.2% on dry weight basis of the grains. The spawn were tested viz., paddy spawn, maize

additives were thoroughly and evenly mixed (broken) spawn, sorghum spawn, and kurakkan

with the grains. The grain medium was filled in spawn.

to polypropylene bags (200 gauges, 37.5 cm

long, and 17.5 cm wide). About 200 g of Data analysis

medium was packed in each bag. The bags were Data were analyzed using the analysis of

sealed using cotton wool plugged conduit/ poly variance (ANOVA) procedure by SAS and

vinyl chloride pipe rings, and covered by a piece means were separated using Duncan’s Multiple

of paper by tying a rubber band around the neck. Range Test (DMRT) at p = 5%.

The bags were autoclaved at 121oC, 15 psi, for

30 min and the sterilized bags were allowed to

cool for 24 hours. The bags were immediately RESULTS

inoculated with mycelial culture of P. ostreatus

maintained on PDA. Kurakkan spawn (T2) showed a faster rate of

mycelium growth (Fig. 1) during the spawn run.

Media preparation Paddy spawn showed a markedly slow rate of

A medium was prepared using sawdust of mycelium growth in relation to all other spawn

mango, rice bran (at the rate of 10%), chalk (at types. Kurakkan spawn (T2) showed the highest

the rate of 2%), and epsom (at the rate of 0.2%) rate of spawn run of 0.827cm/ day, while it was

on the dry weight basis of the substrate and were 0.797, 0.763, and 0.524 cm/day for maize (T3),

mixed thoroughly with water. The correct water for sorghum (T1) and paddy (T4), respectively.

content was checked by pressing the medium by

hand. The medium was filled into polypropylene There were significant differences in the

bags. About 800 g of medium was packed into days taken for completion of spawn run between

each bag. paddy spawn and others viz., sorghum,

kurakkan, and broken maize (Table 1). Paddy

The bags were then sealed, autoclaved and spawn was significantly different from the other

inoculated with the four types of spawn sorghum three types of spawn in taking the longest period

(T1), kurakkan (T2), maize (T3), and paddy of 32 ± 2 days for the completion of spawn run

(T4). Sawdust substrate in bags were inoculated (Table 1). Sorghum, kurakkan, and broken

with approximately 2 g of spawn using surface maize took 23 ± 1, 21 ± 1, and 22 ± 1 days for

spawning technique under laminar flow and the completion of spawn run respectively. Days

incubated in a dark chamber. for pinhead formation was longest in paddy

spawn (50 ± 1 days), while sorghum, kurakkan,

Determination of spawn run and broken maize took 36 ± 1, 35 ± 1, and 45 ±

The growth of mycelium (linear length) in 1 days for pinhead formation, respectively (Fig.

each bag was measured by a measuring tape at 6 2).

day intervals. Using this data, spawn run rate

(cm/day) was determined for every spawn type. Time taken for the first flush, was also

When the mycelium fully covered the substrate longest in paddy spawn (43 ± 1 days) while

bag (spawn run completed), bags were kept open

Cultivation of Oyster Mushroom on Sawdust 179

sorghum, kurakkan, and broken maize took 32 ± efficiency (BE) of five harvests among the four

1, 31 ± 1, and 38 ± 1 days, respectively. different spawn types (Table 2) with maize and

paddy having similar efficiency.

Total mushroom yield differed significantly

among the four types of grain spawns tested Highest BE was recorded for the harvests

(Table 2). Highest fresh weight (yield) of 276.87 obtained from kurakkan spawn (30.76 ± 0.01)

± 0.30 g was obtained with kurakkan spawn (T2) which significantly differed from that of the

followed by sorghum (T1), maize (T3), and other three spawn types. Sorghum recorded the

paddy (T4) of 228.45 ± 0.29, 149.15 ± 0.30, and second highest (25.38 ± 0.05) for BE, which

107.87 ± 0.30 g, respectively. There were significantly differed from BE of maize and

significant differences in the mean biological paddy spawns.

Linear Length (cm)

Incubation (Days)

Figure 1. Time course of spawn running using different spawn types to inoculate sawdust based

substrate.

Table 1. Spawn Run: Length of mycelia over time.

Spawn Type Spawn Run (cm)

th th

7 Day 14 Day 21st day

Sorghum (T1) 3.533 ± 0.257 b 9.875 ± 0.760 a 16.033 ± 0.601 b

Kurakkan (T2) 4.667 ± 0.629 a 11.014 ± 1.658 a 17.375 ± 0.705 a

Maize (T3) 3.95 ± 0.180 ab 10.142 ± 0.302 a 16.75 ± 0.661 ab

Paddy (T4) 2.00 ± 0.508 c 5.902 ± 0.806 b 11.00 ± 0.500 c

Values followed by the same letter in a row are not significantly different at p=0.05 - DMRT.

Pathmashini et al. 180

Days

Spawn type

Figure 2. Days for spawn running, pinhead formation, flushing and harvesting of different spawn

types.

Table 2. Interaction of spawn types on sawdust.

Time in days Spawn Types

(Mean±SD) Sorghum (T1) Kurakkan (T2) Maize (T3) Paddy (T4)

Spawn run 23 ± 1 b 21 ± 1 b 22 ± 1 b 32 ± 2 a

Pinhead 36 ± 1 c 35 ± 1 c 45 ± 1 b 50 ± 1 a

c c

Flush 32 ± 1 31 ± 1 38.33 ±1 b 43 ± 1 a

b a

Harvest 48.85 ± 0.67 52.94 ± 0.67 24.35 ± 1.37 c 19.37 ± 1.58 d

¶ b a

Total Yield (g) 228.45± 0.29 276.87± 0.30 149.15±0.30 c 107.87± 0.30 d

* b a

Mean Yield (g) 45.69± 0.67 55.37 ± 0.67 29.83 ± 1.37 c 21.57 ± 0.37 d

┼ b a

BE % 25.38 ± 0.05 30.76 ± 0.01 16.57 ± 0.67 c 11.99 ± 0.67 c

¶

Total fresh weight of five harvests.

*

Mean yield of five harvests.

┼

Accumulated BE %, the ratio of fresh mushroom harvested/ initial dry weight of substrate expressed

as a percentage.

Values followed by different letters in a row differ significantly at p=0.05 based on DMRT.

DISCUSSION The findings of the spawn run did not agree

with those of Ahmed (1986) who stated that P.

The days taken for the completion of spawn ostreatus completed the spawn run in 17 – 20

run except for paddy spawn, were in agreement days and pinheads formation in 23 – 27 days.

with the findings reported by Shah et al. (2004) Shah et al. (2004) reported 24 days for pinheads

and Tan (1981) where the spawn run took three formation on sawdust medium. The days for

weeks. pinhead formation and days for flush (fruiting

bodies) formation recorded in this study were

Variations in spawn run rate may be longer than previous findings. This may

attributed to the size of the grains. Smaller probably be associated with the temperature and

grains have a greater number of inoculation humidity. Study by Shah et al. (2004) was

points per kg than larger grains (Mamiro and conducted at 25oC where spawn running and

Royse, 2008). It was found that the spawn run pinhead formation were observed. Quimo (1976,

rate of smaller grains was higher than the larger 1978) too reported that fruiting bodies appear 3

grains. However, larger grains have a greater – 4 weeks after inoculation of spawn while Shah

food reserve (Elliot, 1985) and can sustain the et al. (2004) stated that pinheads appear 27 – 34

mycelium for longer periods of time during days after inoculation at 17 – 20o C.

stress (Fritsche, 1988). Thus, different types of

spawn may influence productivity and growth. This finding on the yield contrasted with the

results of Shah et al. (2004) and seems relatively

Cultivation of Oyster Mushroom on Sawdust 181

low compared to commercial production and REFERENCES

was probably associated with the substrate

(sawdust). Shah et al. (2004) recorded maximum Ahmed, I. (1986). Some studies on oyster

yield of 646.9 g for three harvests through a mushroom (Pleurotus spp.) on waste material

different cultivation technique. Shah et al. for corn industry. M.Sc. Thesis, University of

(2004) adopted fermentation of substrates Agriculture, Faisalabad, Pakistan. Pp. 25 – 50.

(sawdust) for five days to boost the yield and the

temperature was maintained at 17 – 20o C Annonymous. World Bank Report. High Food

throughout the period of fructification (flush Prices - A Harsh New Reality. Retrieved on

forming). Bano and Srivastava (1962) recorded a www.econ.worldbank.org as on 7/15/2008.

yield of 22 g of total fresh weight.

Arulnandhy, V. and Gayathri, T. (2007).

Arulnandhy and Gayathri (2007) obtained a Identification of suitable and efficient substrate

mean yield of 24 g on sawdust medium while for the production of oyster (Pleurotus

Obodai and Vowotor (2002) obtained a mean ostreatus) mushrooms. Undergraduate research

yield of 25.5 g. Compared to these findings we report, Department of Agricultural Biology,

obtained higher mean yields for sorghum (45.69 Faculty of Agriculture, Eastern University, Sri

g), kurakkan (55.37 g) and maize (29.83 g) and Lanka.

comparable yield for paddy (21.57 g) spawns.

Bahl, N. (1998). Hand book on mushrooms.

Bano and Srivastava (1962) obtained a mean Oxford & IBH Publishing co Pvt Ltd. Pp.15-40.

yield of 60 g by using sawdust and straw in the

ratio of 1:1, while Arulnandhy and Gayathri Bano, Z. and Srivastava., H.C. (1962). Studies

(2007) obtained 55 g using the same substrate on the cultivation of Pleurotus species on paddy

composition. When sawdust was incorporated straw. Food Science 11(12): 363 – 365.

with dry leaves Arulnandhy and Gayathri (2007)

obtained a mean yield of 22 g and with shredded Chang, S.T. (1999). World production of

paper a mean yield of 47 g. Sawdust cultivated and medicinal mushrooms in 1997

incorporated with substrates like straw and with emphasis on Lentinus edodes. International

grasses (Udugama and Ranjani, 1997), shredded Journal of Medicinal Mushrooms. 1: 291 – 300.

paper (Arulnandhy and Gayathri, 2007)

enhanced the yield rather than sawdust alone. Das, N. and Mukherjee, M. (2007). Cultivation

of Pleurotus ostreatus on weed plants.

BioResource Technology 98: 2723 – 2726.

CONCLUSION www.science direct.com retrieved on

07/08/2007.

Kurakkan spawn showed the highest rate of

spawn run of 0.827cm/ day. Kurakkan spawn Elliot, T.J. (1985). Spawn – making and Spawns.

was found to be the most efficient spawn type In: The Biology and Technology of the

for growth in the sawdust medium compared to Cultivated Mushrooms, P.B. Flegg, D.M.

other spawns tested. Paddy spawn took Spencer and D.A. Wood (Eds.), John Wiley &

significantly longer time for spawn running, Sons Ltd. Pp. 131– 139.

flush formation, and days for harvest. Kurakkan

spawn produced the highest mean yield of 55.37 Eswaran, A. and Ramabadran, R. (2000).

± 0.30 g and fresh mushroom yield percentage of Studies on some physiological, cultural and post

30.76 ± 0.01. Thus kurakkan is the best spawn harvest aspects of oyster mushroom, Pleurotus

type among the four spawn types tested. eous. Tropical Agricultural Research. 12: 360 –

374.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Fritsche, G. (1988). Spawn: properties and

preparation, In: The Cultivation of Mushrooms.

We express our sincere gratitude to the van Griensven, L.J.L.D. (Eds.), Darlington

World Bank funded IRQUE project for Mushroom Laboratories, Sussex. Pp. 1–99.

providing funds for this study.

Hami, H. (1990). Cultivation of oyster

mushroom on sawdust of different woods. M.Sc.

Thesis, University of Agriculture, Faisalabad,

Pakistan.

Pathmashini et al. 182

Mamiro, D.P. and Royse, D.J. (2008). The Royse, D.J. (2002). Influence of spawn rate and

influence of spawn type and strain on yield, size commercial delayed release of nutrient levels on

and mushroom solids content of Agaricus Pleurotus conocopiae yield, size and time to

bisporus produced on non-composted and spent production. Applied Microbiology and

mushroom compost, Bioresource Technology. Biotechnology. 17: 191 – 200.

99 (8): 3205-3212. www.sciecedirect.com

retrieved on 07/08/2007. Shah, Z.A., Ashraf, M. and Ishtiaq, M. (2004).

Comparative study on cultivation and yield

Obodai, M. and Vowotor, K.A. (2002). performance of oyster mushroom (Pleurotus

Performance of different strains of Pleurotus ostreatus) on different substrates (wheat straw,

species under Ghanaian conditions. Journal of leaves, sawdust). Pakistan Journal of Nutrition.

Food Technology in Africa. 7 (3): 98-100. 3 (3): 158 – 160.

Quimo, T.H. (1976). Cultivation of Ganoderma Tan, T.T. (1981). Cotton waste is a fungus

the Pleurotus-way. Mushroom Newsletter for the (Pleurotus). Good substrate for cultivation of

Tropics 6: 12 – 13. Pleurotus ostreatus the oyster mushroom.

Mushroom Science. 11: 705 – 710.

Quimo, T.H. (1978). Indoor cultivation of

Pleurotus ostreatus. Phillipines Agriculturist, Udugama, S. and Ranjini, S. (1997). Mushroom

61: 253 – 262. as an agent of recycling wild grass to an edible

food for man. Annual Sessions of the

Department of Agriculture (ASDA). 53:8.

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Multicell - Multi-Channel and Multi-Function Transmitter/ControllerDocument29 pagesMulticell - Multi-Channel and Multi-Function Transmitter/Controllerawal ismailNo ratings yet

- Diffuser Pipe: Piping BOQ SummaryDocument1 pageDiffuser Pipe: Piping BOQ Summaryawal ismailNo ratings yet

- PL 4 - Flowmeter, Monting Pad N FilterDocument2 pagesPL 4 - Flowmeter, Monting Pad N Filterawal ismailNo ratings yet

- Effect of Different Substrate Supplement PDFDocument8 pagesEffect of Different Substrate Supplement PDFawal ismailNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Botanical Society of AmericaDocument12 pagesBotanical Society of AmericaAndrew ButcherNo ratings yet

- Perspective in Mathematics Vi: The Decline and Revival of Learning: Fibonacci SequenceDocument40 pagesPerspective in Mathematics Vi: The Decline and Revival of Learning: Fibonacci SequenceRieynie AhmedNo ratings yet

- Palmyra HDocument5 pagesPalmyra HKaren MapaNo ratings yet

- SA Citrus Grower, Katlego Sitrus, To Attend Fruit Logistica in BerlinDocument2 pagesSA Citrus Grower, Katlego Sitrus, To Attend Fruit Logistica in BerlinMary Joy Dela MasaNo ratings yet

- 797-20190612-055548article - Tablang Et AlDocument8 pages797-20190612-055548article - Tablang Et AlRon Patrick CamposNo ratings yet

- ICSE BiologyDocument10 pagesICSE BiologysubhaseduNo ratings yet

- Stability Indicating HPLC Method For Determination of Myrsinoic Acids A and B in Rapanea Ferruginea Extracts and NanoemulsionsDocument11 pagesStability Indicating HPLC Method For Determination of Myrsinoic Acids A and B in Rapanea Ferruginea Extracts and NanoemulsionsBruna XavierNo ratings yet

- Biology Diagram McqsDocument23 pagesBiology Diagram McqsFatima Obaid0% (1)

- Dryad, Cherry Blossom by Deb LievenDocument3 pagesDryad, Cherry Blossom by Deb LievenDebraLievenNo ratings yet

- Lesson 3 - The Cell Unit Review TrashketballDocument70 pagesLesson 3 - The Cell Unit Review Trashketballapi-140174622No ratings yet

- EnglishDocument4 pagesEnglishJejeNo ratings yet

- 09.diaphragm ActuatorDocument5 pages09.diaphragm Actuatorprihartono_diasNo ratings yet

- Tommy Bahama MenuDocument6 pagesTommy Bahama MenuMellowZenGuruNo ratings yet

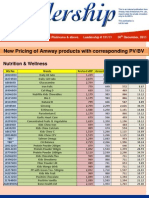

- New Pricing of Amway Products With Corresponding PV/BV: Nutrition & WellnessDocument4 pagesNew Pricing of Amway Products With Corresponding PV/BV: Nutrition & WellnessAbhiyant SaxenaNo ratings yet

- The Window or The Songs of The WrensDocument107 pagesThe Window or The Songs of The WrensJacob KerznerNo ratings yet

- Sandalwood Cultivation: Uses and Health Benefits of SandalwoodDocument4 pagesSandalwood Cultivation: Uses and Health Benefits of SandalwoodBhushan GosaviNo ratings yet

- WORKSHEET 2.1 Animal and Plant CellDocument3 pagesWORKSHEET 2.1 Animal and Plant CellLim Wai Wai100% (1)

- Year 7 Variation-WorksheetDocument17 pagesYear 7 Variation-WorksheetCally ChewNo ratings yet

- Research 1 - Module 2Document4 pagesResearch 1 - Module 2Arnold CabanerosNo ratings yet

- 511 Cropping System SSR MCR PDFDocument92 pages511 Cropping System SSR MCR PDFNam Dinh100% (1)

- Hayward EC65A ManualDocument12 pagesHayward EC65A ManualAllsysgoNo ratings yet

- S T I S: Itio Arget Ntegrated ChoolDocument4 pagesS T I S: Itio Arget Ntegrated Chooljam syNo ratings yet

- Indian Food Processing IndustryDocument82 pagesIndian Food Processing Industrywimiza237590No ratings yet

- Sagada OrangeDocument5 pagesSagada OrangeAnonymous BkyI0BNo ratings yet

- An Overlooked Asset Hydrodynamic Speed Control in Combined Cycle Power PlantsDocument4 pagesAn Overlooked Asset Hydrodynamic Speed Control in Combined Cycle Power Plantsmfhaleem@pgesco.comNo ratings yet

- Bonnie PlantsDocument24 pagesBonnie PlantsLWNo ratings yet

- 1409 Lab ManualDocument155 pages1409 Lab Manualbunso padillaNo ratings yet

- White Chicken KormaDocument5 pagesWhite Chicken Kormamkm2rajaNo ratings yet

- WORKSHEET 2.2 Cell Structure and Function: ScoreDocument4 pagesWORKSHEET 2.2 Cell Structure and Function: ScoreCHONG KOK HIN MoeNo ratings yet

- Steel Industry IntroductionDocument8 pagesSteel Industry IntroductionAmitNo ratings yet