Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2 Guide To Classroom Deliberation For Students and Teachers 9.30.16 PDF

2 Guide To Classroom Deliberation For Students and Teachers 9.30.16 PDF

Uploaded by

Kharl FulloOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2 Guide To Classroom Deliberation For Students and Teachers 9.30.16 PDF

2 Guide To Classroom Deliberation For Students and Teachers 9.30.16 PDF

Uploaded by

Kharl FulloCopyright:

Available Formats

Last Update: September 30, 2016

Guide to Classroom Deliberation for Students and Teachers

Building on the work of the Bioethics Commission in Bioethics for Every Generation:

Deliberation and Education in Health, Science, and Technology, this guide to

deliberation provides instructors and students with a condensed overview of how to

conduct classroom training in deliberation as a decision-making method. Adapting and

building upon the process described in Appendix I of Bioethics for Every Generation,

this guide is intended for instructors and students to use in combination with specific

“Deliberative Scenarios” available at bioethics.gov.

Introduction

Democratic deliberation is an inclusive method of decision making used to address an

open question or decide on a way forward. It requires a diverse set of participants to

consider both relevant empirical information as well as ethical and moral bases for

decisions. Participants justify their arguments with reasons that are accessible to all

participants and treat one another with mutual respect, with the goal of reaching an

actionable decision on how to move forward (such as a rule, policy, or law). The method

includes openness to future challenge or revision should additional information emerge.

Practicing deliberation in the classroom requires active participation and helps prepare

students to make collaborative decisions that embrace respectful exploration and

discussion of opposing views. Deliberation calls for students to work toward agreement

when it is possible and to maintain mutual respect when it is not. It encourages

participants to adopt a broader perspective and work toward a mutually agreeable

conclusion.

Democratic deliberation is a decision-making method that works well when a group is

faced with an open policy question on which reasonable disagreement exists. The method

addresses the question ‘what should we do?’ especially when there are several reasonable

options for action. Deliberation requires articulation of values and ethical considerations

in addition factual and empirical evidence, including lived experience. While science tells

us what we can do, ethics helps us decide what we should do.

Deliberation is different than discussion or debate. Discussion is typically used to help

participants develop an understanding of a topic. Debate is typically used as a means of

swaying or convincing an opponent of the rightness of one’s position. Deliberation, on

the other hand, is typically used to reach an agreed-upon way forward on a challenging

topic for which there are several reasonable alternatives. Often it involves discussion (i.e.,

Guide to Classroom Deliberation for Students and Teachers 1

Last Update: September 30, 2016

developing an understanding) but does not involve the typical winner-take-all approach

often associated with debate. The aim is to reach a negotiated way forward that finds

common ground and meaningful agreement.

Conducting Democratic Deliberation in the Classroom

Before the Deliberation

Step 1: Choose an open question and consider distinct points of view. An open question

requires consideration of facts as well as social values. Open questions can be seen from

multiple perspectives. The question should have an applied component, including

questions about how best to move forward and what should be done. Each “Deliberative

Scenario” will present an open policy question. Group reflection on what makes it an

open policy question can help set the stage for deliberation.

Step 2: Allow ample time for deliberation. Deliberation is a reflective process, which

requires time. In the case of an urgent situation, conduct deliberation simultaneously, and

apply results as soon as possible. Consider the time-sensitive nature of the current

question and how long you have available for deliberation. These considerations might

determine the extent and content of background preparation before deliberation. Be sure

to dedicate some of the available time for articulating recommendations or developing a

concrete proposal. Build time into the process for assessment.

During the Deliberation

Step 3: Use sound and relevant information to inform the deliberation. Make established

facts and perspectives available to all participants in the form of accessible background

materials. Successful proposals for a way forward require developing a shared knowledge

base. Scenarios will include background readings to help form a common ground. If new

information emerges, introduce it into the deliberation. Evaluate evidence through an

established and reliable mechanism before and during deliberation.

A “Teacher Companion” to each “Deliberative Scenario” will include suggested

background readings for this step. Instructors might seek out supplemental resources on

their own to tailor scenarios to their classroom needs. Classes with more allotted time can

encourage students to actively participate in seeking out relevant background information

before and during the deliberation. In addition to shared background readings for all

participants, those assigned various roles for deliberation might have corresponding

readings that inform the perspective that each participant brings to deliberations.

Guide to Classroom Deliberation for Students and Teachers 2

Last Update: September 30, 2016

“Teacher Companions” will outline these optional readings for various roles. In addition,

“Teacher Companions” include optional Scenario Shifts that instructors can introduce at

their discretion as deliberation unfolds. Scenario Shifts provide key expert insights or

points of emerging information that might change the direction of the deliberation.

Step 4: Cultivate an environment that encourages participants in the deliberation to

practice mutual respect and reason-giving. In preparation for deliberation, participants

might discuss what behaviors do and do not constitute respect for other participants. As

deliberation unfolds, students must consider what adequate respect for differing

perspectives in a democracy looks like in practice, and whether their own or others’

attitudes and behavior reflect democratic ideals of inclusivity and equality. Instructors

must be prepared to facilitate deliberation, including managing disagreement when

participants are unable to and asking students to consider views that have not yet been

raised. In addition, teachers might spot moments to assist participants in overcoming

obstacles to productive deliberation. Equally important, instructors must evaluate

emerging consensus, watching for hidden assumptions, perspectives that have been

overlooked, or considerations that have been prematurely dismissed. Teachers must

address their own biases, and critically reflect on the decision to interject their own

views—implicit or explicit—into deliberation. The Additional Resources section below

provides teachers with more tips on how to foster open discussion, as well as more

information on seeking out institutional and administrative support for deliberative

classroom activities.

After the Deliberation

Step 5: Develop detailed, actionable recommendations or a proposal. Recommendations

or a clear proposal for action require participants to articulate areas of agreement, even if

other aspects of the question remain disputed or unsettled. Participants should consider

how to format and share their findings and recommendations with policymakers to ensure

that the results of their deliberations are considered in the policymaking process.

Participants might also consider how deliberation is often iterative. They might identify

key points in time for revisiting the proposed solution, or anticipate crucial emerging

information that might suggest a need to begin deliberations anew. While

recommendations or a draft proposal can provide a product that teachers might deem an

appropriate object for assessment purposes, deliberation emphasizes the process of

learning, not just the product. For this reason, student and instructor reflections on how

deliberations went, and how they might be improved, should also constitute a central

object of assessment. The Additional Resources section below provides participants and

teachers with more information about how to use reflections in assessment of deliberative

classroom exercises.

Guide to Classroom Deliberation for Students and Teachers 3

Last Update: September 30, 2016

Additional Resources

General

Alfaro, C. (2008). Chapter 6: Reinventing teacher education: The role of deliberative

pedagogy in the K-6 Classroom. In Dedrick, J.R., L. Grattan, and H. Dienstrfrey. (Eds.).

Deliberation and the Work of Higher Education (pp. 143-164). Dayton, OH: The

Kettering Foundation Press.

Bogaards, M. and F. Deutsch. (2015). Deliberation by, with, and for University Students.

Journal of Political Science Education, 11(2), 221-232.

Hess, D. (2009). Controversy in the Classroom. New York, NY: Routledge.

Jhumki Basu, S., Calabrese, A. and E.T. Barton. (Eds.). (2011). Democratic Science

Teaching: Building the Expertise to Empower Low-Income Minority Youth in Science.

Rotterdam, Netherlands: Sense Publishers.

Morse, R.S., et al. (2005). Learning and teaching about deliberative democracy: On

campus and in the field. Journal of Public Affairs Education, 11(4), 325-336.

Parker, W.C. (2003). Teaching Democracy: Unity and Diversity in Public Life. New

York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Fostering Support of Parents, Schools, and Administration

Hess, D.E., and P. McAvoy. (2015). Chapter 10: Supporting the Political Classroom. In

The Political Classroom: Evidence and Ethics In Democratic Education. New York, NY:

Routledge, pp. 204-212.

How to Facilitate Discussion, Handle Instructor Biases Responsibly

Brookfield, S.D. (2005). Discussion as a Way of Teaching: Tools and Techniques for

Democratic Classrooms. Second Edition. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Hess, D.E., and P. McAvoy. (2015). Chapters 8, 9: The Ethics of Framing and Selecting

Issues; The Ethics of Withholding and Disclosing Political Views. In The Political

Classroom: Evidence and Ethics In Democratic Education. New York, NY: Routledge,

pp. 158-203.

Guide to Classroom Deliberation for Students and Teachers 4

Last Update: September 30, 2016

Assessment

Handout 3: Student Reflection on Deliberation. From Lesson Procedures. Deliberating in

a Democracy. Available at:

http://www.did.deliberating.org/documents/Lessons_Procedures.pdf.

Student Rubric for Deliberative Dialogue. The Choices Program. The Center for Foreign

Policy Development at Brown University and the Public Agenda Foundation. Available

at http://www.choices.edu/resources/rubrics/rubric-student-deliberative-dialogue.pdf.

Guide to Classroom Deliberation for Students and Teachers 5

You might also like

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument10 pagesReview of Related LiteratureJhon Ronald TrampeNo ratings yet

- Warnaz Zrar AbdullahDocument9 pagesWarnaz Zrar AbdullahEnglish TutorNo ratings yet

- Critical Thinking in A Distributed Environment:: A Pedagogical Base For The Design of Conferencing SystemsDocument27 pagesCritical Thinking in A Distributed Environment:: A Pedagogical Base For The Design of Conferencing SystemsGlenn E. DicenNo ratings yet

- DebateDocument4 pagesDebateSukanya NayarNo ratings yet

- Basic Principles of Curriculum and InstructionFrom EverandBasic Principles of Curriculum and InstructionRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Effective Clasroom DiscussionDocument5 pagesEffective Clasroom Discussionsoliloquium47No ratings yet

- Table Talk StrategyDocument3 pagesTable Talk Strategyapi-248208787No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument15 pagesUntitledAyesha MalickkNo ratings yet

- GED203 - Week 1 - Learner GuideDocument16 pagesGED203 - Week 1 - Learner GuideMarvin OrbigoNo ratings yet

- ShabuDocument14 pagesShabuprecious.aguilarNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Teachers’ Questions and Tasks to Develop Reading Comprehension: The Application of the Cogaff Taxonomy in Developing Critical Thinking Skills in MalaysiaFrom EverandAn Investigation of Teachers’ Questions and Tasks to Develop Reading Comprehension: The Application of the Cogaff Taxonomy in Developing Critical Thinking Skills in MalaysiaNo ratings yet

- Teachers of English To Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL) TESOL QuarterlyDocument17 pagesTeachers of English To Speakers of Other Languages, Inc. (TESOL) TESOL QuarterlyAye Kyi PhyuNo ratings yet

- Think-Pair or Group-ShareDocument10 pagesThink-Pair or Group-ShareKaren DellatanNo ratings yet

- Discussion MethodDocument11 pagesDiscussion MethodAnusha50% (2)

- Action ResearchDocument6 pagesAction ResearchJeraldgee Catan DelaramaNo ratings yet

- Chapter Take Aways 1-14Document19 pagesChapter Take Aways 1-14api-307989771No ratings yet

- Getting Horses To DrinkDocument8 pagesGetting Horses To Drinkapi-300172472No ratings yet

- Participatory Action Research for Evidence-driven Community DevelopmentFrom EverandParticipatory Action Research for Evidence-driven Community DevelopmentNo ratings yet

- Readings For Liberation Studies & Psychology CourseDocument15 pagesReadings For Liberation Studies & Psychology Coursekwame2000No ratings yet

- Collaborative Versus Cooperative LearningDocument14 pagesCollaborative Versus Cooperative Learningshiba3No ratings yet

- Develop the Territory Under Your Hat—Think!: Critical Thinking: a Workout for a Stronger MindFrom EverandDevelop the Territory Under Your Hat—Think!: Critical Thinking: a Workout for a Stronger MindNo ratings yet

- Academic Advising Approaches: Strategies That Teach Students to Make the Most of CollegeFrom EverandAcademic Advising Approaches: Strategies That Teach Students to Make the Most of CollegeJayne K. DrakeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Why Is Active Learning Important?Document3 pagesWhy Is Active Learning Important?AlexxaNo ratings yet

- Example of Group ActivitiesDocument9 pagesExample of Group ActivitiesJustine Joi GuiabNo ratings yet

- Educational Goods: Values, Evidence, and Decision-MakingFrom EverandEducational Goods: Values, Evidence, and Decision-MakingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- 8 Takeaways Creating Engaging DiscussionsDocument2 pages8 Takeaways Creating Engaging DiscussionsEric Machan Howd100% (1)

- Active Learning StrategiesDocument5 pagesActive Learning StrategiesQushoy Al IhsaniyNo ratings yet

- Catalyst: An evidence-informed, collaborative professionallearning resource for teacher leaders and other leaders workingwithin and across schoolsFrom EverandCatalyst: An evidence-informed, collaborative professionallearning resource for teacher leaders and other leaders workingwithin and across schoolsNo ratings yet

- Debating in Language B:: A Practical Guide For Engaging and Empowering Language LearnersDocument47 pagesDebating in Language B:: A Practical Guide For Engaging and Empowering Language LearnersValentina DimitrovaNo ratings yet

- Demonstrations: Suggested Citation:"Chapter 2: How Teachers TeachDocument10 pagesDemonstrations: Suggested Citation:"Chapter 2: How Teachers TeachRahib LashariNo ratings yet

- Dilgash Rasheed RasulDocument9 pagesDilgash Rasheed RasulEnglish TutorNo ratings yet

- BimpongDocument7 pagesBimpongTwumasi EricNo ratings yet

- Traditional Training MethodsDocument57 pagesTraditional Training Methodsmohit_roy_8No ratings yet

- Final Deliberation ReportDocument4 pagesFinal Deliberation Reportapi-548278058No ratings yet

- Educ 5270 Discussion Forum WK3Document2 pagesEduc 5270 Discussion Forum WK3Oganeditse TshereNo ratings yet

- Discussion SectionsDocument19 pagesDiscussion SectionsdamadolNo ratings yet

- Leadership Dialogues: Conversations and Activities for Leadership TeamsFrom EverandLeadership Dialogues: Conversations and Activities for Leadership TeamsNo ratings yet

- Debate: Prepared by Sreelakshmi Prathapan English Pedagogy SN College of Teacher Education, MuvattupuzhaDocument11 pagesDebate: Prepared by Sreelakshmi Prathapan English Pedagogy SN College of Teacher Education, Muvattupuzhasreelakshmi pNo ratings yet

- Theory and Credibility: Integrating Theoretical and Empirical Social ScienceFrom EverandTheory and Credibility: Integrating Theoretical and Empirical Social ScienceNo ratings yet

- The Discussion Method in Classroom TeachingDocument7 pagesThe Discussion Method in Classroom Teachingapi-283257062100% (1)

- Eea 532 Instructional Strategies Comparison Eryn WhiteDocument9 pagesEea 532 Instructional Strategies Comparison Eryn Whiteapi-617772119No ratings yet

- A Definitive White Paper: Systemic Educational Reform (The Recommended Course of Action for Practitioners of Teaching and Learning)From EverandA Definitive White Paper: Systemic Educational Reform (The Recommended Course of Action for Practitioners of Teaching and Learning)No ratings yet

- Unit 3-2Document18 pagesUnit 3-2hajraNo ratings yet

- Lesson Study Project Showcase Catl@uwlax - EduDocument10 pagesLesson Study Project Showcase Catl@uwlax - EduLesson Study ProjectNo ratings yet

- 08 Thinking Together PDFDocument10 pages08 Thinking Together PDFMariano CastellaroNo ratings yet

- Interactive Teaching StrategiesDocument13 pagesInteractive Teaching StrategiesSeham FouadNo ratings yet

- Reflective Practice for Educators: Professional Development to Improve Student LearningFrom EverandReflective Practice for Educators: Professional Development to Improve Student LearningNo ratings yet

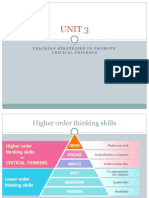

- Unit 3: Teaching Strategies To Promote Critical ThinkingDocument18 pagesUnit 3: Teaching Strategies To Promote Critical ThinkingBint e HawwaNo ratings yet

- Unit 06Document35 pagesUnit 06ShahzadNo ratings yet

- What Is The Socratic Method?: Named For The Famed Greek Philosopher Socrates (Document3 pagesWhat Is The Socratic Method?: Named For The Famed Greek Philosopher Socrates (AhsanNo ratings yet

- Group 5 Advanced PhilosophyDocument25 pagesGroup 5 Advanced Philosophyeugene louie ibarraNo ratings yet

- Theme 1: Planning Educational ResearchDocument79 pagesTheme 1: Planning Educational Researchcinthya quevedoNo ratings yet

- Written ReportDocument6 pagesWritten ReportJohn Philip ParasNo ratings yet

- Collab ConversationDocument5 pagesCollab ConversationIuliaNo ratings yet

- ID Act, 1947Document22 pagesID Act, 1947Abubakar MokarimNo ratings yet

- Fernando McKenna Article-LibreDocument8 pagesFernando McKenna Article-Librejerry lee100% (2)

- Full Download Ebook Ebook PDF Media and Communication in Canada Networks Culture Technology Audience Ninth 9th Edition PDFDocument42 pagesFull Download Ebook Ebook PDF Media and Communication in Canada Networks Culture Technology Audience Ninth 9th Edition PDFlillie.christopher194100% (42)

- Laboratory Exercise 06Document3 pagesLaboratory Exercise 06قدیر آفریدیNo ratings yet

- Name Your Own Price: Case Study ReportDocument5 pagesName Your Own Price: Case Study ReportVeer KorraNo ratings yet

- ECE3010 Antennas-And-Wave-Propagation TH 1.1 AC40Document2 pagesECE3010 Antennas-And-Wave-Propagation TH 1.1 AC40YashawantBasuNo ratings yet

- Bailey & Love MCQs-EMQs in Surgery-Part - 2Document10 pagesBailey & Love MCQs-EMQs in Surgery-Part - 2JockerNo ratings yet

- KH Coder Tutorial Using Anne of Green Gables:: A Two-Step Approach To Quantitative Content Analysis Koichi HiguchiDocument35 pagesKH Coder Tutorial Using Anne of Green Gables:: A Two-Step Approach To Quantitative Content Analysis Koichi HiguchiAlbertNo ratings yet

- Wilson N.G., From Byzantium To Italy, Greek Studies in The Italian Renaissance - 1992 (001-030)Document30 pagesWilson N.G., From Byzantium To Italy, Greek Studies in The Italian Renaissance - 1992 (001-030)Katerina TsoutsikaNo ratings yet

- Interesting Facts About Japanese School SystemDocument5 pagesInteresting Facts About Japanese School SystemJahara Mae CalmaNo ratings yet

- Unit 6 - Week 5: Assignment 5Document4 pagesUnit 6 - Week 5: Assignment 5shubhamNo ratings yet

- IRobot WorksheetDocument2 pagesIRobot Worksheetgioconda1100% (6)

- Lead Small TeamsDocument92 pagesLead Small TeamsMarizon Pagalilauan MuñizNo ratings yet

- Kin 366 - PresentationDocument11 pagesKin 366 - Presentationapi-568558610No ratings yet

- MusicDocument3 pagesMusicDANGOY, CHRYSXIANNE D.BEEDNo ratings yet

- Extra Exam Practice: Present Simple or Present ContinuousDocument6 pagesExtra Exam Practice: Present Simple or Present ContinuousNoeliaNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan On Solving Right TriangleDocument5 pagesLesson Plan On Solving Right TriangleDirham Bantilan Tagmaya83% (6)

- Kellyjns20 302 SJRESUMEDocument2 pagesKellyjns20 302 SJRESUMEapi-25467097No ratings yet

- Reading Practice7Document17 pagesReading Practice7Marlon N HexNo ratings yet

- 104 Law of ContractDocument23 pages104 Law of Contractbhatt.net.inNo ratings yet

- Super StructuresDocument83 pagesSuper StructuresDavid YesayaNo ratings yet

- SP Question BankDocument2 pagesSP Question BankAbhishek GhoshNo ratings yet

- Northern Zambales CollegeDocument25 pagesNorthern Zambales CollegeMae EdquibanNo ratings yet

- Data Analytics QuantumDocument148 pagesData Analytics QuantumShivam SinghNo ratings yet

- Shrek 2Document211 pagesShrek 2Ferdinand KaasjeNo ratings yet

- Tristyn Mandel: EducationDocument2 pagesTristyn Mandel: Educationapi-346876013No ratings yet

- Shynn Faith MDocument3 pagesShynn Faith MMark TadayaNo ratings yet

- Linking Information Systems To The Business PlanDocument10 pagesLinking Information Systems To The Business Planermiyas tesfayeNo ratings yet

- Guia Del Examen de Ingles.Document11 pagesGuia Del Examen de Ingles.Anonymous E5UqPWhkimNo ratings yet

- Contact and Noncontact Forces StationDocument12 pagesContact and Noncontact Forces StationDemanda GookinNo ratings yet