Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Foregein CE PDF

Uploaded by

MeléndezEscobar PatriciaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Foregein CE PDF

Uploaded by

MeléndezEscobar PatriciaCopyright:

Available Formats

Foreign-Body Ingestions of Young

Children Treated in US Emergency

Departments: 1995–2015

Danielle Orsagh-Yentis, MD,a Rebecca J. McAdams, MA, MPH,b Kristin J. Roberts, MS, MPH,b Lara B. McKenzie, PhD, MAb,c

describe the epidemiology of foreign-body ingestions (FBIs) of children ,6 years

OBJECTIVES: To

of age who were treated in US emergency departments from 1995 to 2015.

abstract

METHODS: We performed a retrospective analysis using data from the National Electronic Injury

Surveillance System for children ,6 years of age who were treated because of concern of FBI

from 1995 to 2015. National estimates were generated from the 29 893 actual cases reviewed.

RESULTS: On the basis of those cases, 759 074 children ,6 years of age were estimated to have

been evaluated for FBIs in emergency departments over the study period. The annual rate of

FBI per 10 000 children increased by 91.5% from 9.5 in 1995 to 18 in 2015 (R2 = 0.90; P ,

.001). Overall, boys more frequently ingested foreign bodies (52.9%), as did children 1 year of

age (21.3%). Most children were able to be discharged after their suspected ingestion

(89.7%). Among the types of objects ingested, coins were the most frequent (61.7%). Toys

(10.3%), jewelry (7.0%), and batteries (6.8%) followed thereafter. The rates of ingestions of

those products also increased significantly over the 21-year period. Across all age groups, the

most frequently ingested coin was a penny (65.9%). Button batteries were the most common

batteries ingested (85.9%).

CONCLUSIONS: FBIsremain common in children ,6 years of age, and their rate of ingestions has

increased over time. The frequency of ingestions noted in this study underscores the need for

more research to determine how best to prevent these injuries.

a

Department of Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and bCenter for Injury Research and Policy, The WHAT’S KNOWN ON THIS SUBJECT: Foreign-body

Research Institute, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, Columbus, Ohio; and cDivision of Epidemiology, College of ingestions are common in children. Button battery and

Public Health, The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio magnet ingestions can cause considerable harm and

Dr Orsagh-Yentis conceptualized and designed the study, conducted the analyses, drafted the initial have been the focus of much research and advocacy

manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms McAdams conducted the analyses and to date.

reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Roberts and Dr McKenzie conceptualized and designed

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS: The rate of foreign-body

the study and reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript

as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

ingestion in children ,6 years of age increased by

91.5% during the 21-year study period. The items most

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1988 frequently ingested were coins (61.7%), toys (10.3%),

Accepted for publication Feb 11, 2019 jewelry (7.0%), and batteries (6.8%).

Address correspondence to Danielle Orsagh-Yentis, MD, Department of Gastroenterology,

Hepatology, and Nutrition, Nationwide Children’s Hospital, 700 Children’s Dr, Columbus, OH 43205.

E-mail: danielle.orsagh-yentis@nationwidechildrens.org

PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).

Copyright © 2019 by the American Academy of Pediatrics To cite: Orsagh-Yentis D, McAdams RJ, Roberts KJ, et al.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to Foreign-Body Ingestions of Young Children Treated in US

this article to disclose. Emergency Departments: 1995–2015. Pediatrics. 2019;

143(5):e20181988

FUNDING: No external funding.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on March 5, 2020

PEDIATRICS Volume 143, number 5, May 2019:e20181988 ARTICLE

Young children are prone to putting able to be identified, BBs were a choke-test cylinder (2.25 inches

things in their mouths and culpable 58% of the time. Between long by 1.25 inches wide,

swallowing them.1 Children 5 years of 1995 and 2010, BBs were responsible approximating the expanded size of

age and younger are responsible for for 14 fatalities, all involving young the throat of a child ,3 years of

75% of all foreign-body ingestions children (7 months–3 years of age).8 age).20 In 2012, the CPSC issued

(FBIs),2 and 20% of children 1 to a recall of neodymium magnet sets.21

3 years of age have ingested some Similarly, ingestion of magnets Most companies complied, but the

kind of foreign body.3 In 2016, FBIs (particularly the high-powered ones largest manufacturer of such

were the fourth most common reason composed of neodymium) can be products refused.22 Despite that

for calls to American poison-control harmful. When .1 magnet is company’s refusal, there were 24.8%

centers for children #5 years of age. ingested, the magnets can attract fewer magnet ingestions for children

A total of 67 771 such cases were across gastrointestinal walls, leading #17 years of age between 2013 and

logged that year.4 to perforation, necrosis, sepsis, 2015 than in the 3 years before the

obstruction, and death.9,11 The ban.23

Although many ingested items are ingestion of multiple magnets

relatively innocuous and able to pass appears to have an intestinal Previously published studies on FBIs

through the gastrointestinal tract, perforation rate as high as 50%.13 have been focused on a single type of

some can cause grievous harm, Between 2002 and 2012, there was ingested object or on a short time

necessitating intervention by a 7% increase in surgical frame, and research has been limited

proceduralists or surgeons. According management for patients having on the epidemiology of ingestions

to a single center’s 10-year ingested magnets.14 Of the estimated beyond those of magnets, BBs, and

retrospective review of all its 16 386 children who sought care in coins. Given that children ,6 years of

esophagogastroduodenoscopies, EDs for suspected magnet ingestion age are most likely to ingest foreign

7.8% were done for foreign-body during that time frame, the majority bodies, we sought to explore the

removal alone.5 Adult literature has were ,5 years of age.7 trends of the pantheon of their

revealed that 1% to 14% of patients ingestions from 1995 to 2015. To our

with FBIs require operative removal.6 Although unlikely to cause significant knowledge, this is the first nationally

harm, coins have been shown to be representative study used to examine

The significant morbidity and the objects most frequently ingested the epidemiology of FBIs in US

mortality resulting from ingestions of by children #14 years of age. children presenting to EDs over

magnets and button batteries (BBs) Between 1994 and 2003, there were a 2-decade period.

have been well-documented over the .250 000 such ingestions and/or

past 2 decades.7–9 When BBs become aspirations and 20 resultant deaths in

lodged in the esophagus, they can the United States.15 Children also METHODS

produce hydroxide radicals, leading ingest a variety of other household

to caustic injury from high pH; Data Source

items such as toys and jewelry.16

necrosis, perforation, and strictures Between 2010 and 2014, there were Data of patients ,6 years of age who

can then occur. Aortoenteric fistulas .25 000 ingestions of jewelry among were brought to US EDs for

and death have been reported.9–11 children #18 years of age.17 suspicion of FBI between January 1,

Between 1990 and 2009, the number Approximately 14 children ,5 years 1995, and December 31, 2015, were

of patients presenting to US of age sought care in US EDs each day obtained from the National Electronic

emergency departments (EDs) for because of ingested or inhaled toys Injury Surveillance System (NEISS).

BB-related injuries increased between 1990 and 2011.18 The CPSC operates the NEISS, which

significantly, particularly in the latter provides data on consumer

half of that period. There was an Consumer groups, health care product–related injuries treated in US

average of 3289 annual ED visits for providers, and the CPSC have EDs. Approximately 100 hospitals,

battery-related injuries over those attempted to make toys, batteries, including 8 children’s hospitals,

years.12 In 2012, the Centers for and magnets safer for children. As of provide data to the NEISS, which then

Disease Control and Prevention 2008, under the Consumer Product represents a stratified probability

reported findings of the US Consumer Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA), the sample of the 6100 hospitals in the

Product Safety Commission (CPSC), CPSC requires that manufacturers country that have $6 beds and

relaying that nearly 75% of patients ensure that batteries are secured in a 24-hour ED. Urban, suburban,

seen for battery-related injuries were compartments of toys intended for and rural hospitals are included. By

,5 years of age, with 10% requiring use by children ,3 years of age.19 For using a validated method, data from

hospitalization. When the type of that same age group, they also the NEISS are weighted by the CPSC

battery causing these injuries was banned any toy that could fit within to derive national estimates of

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on March 5, 2020

2 ORSAGH-YENTIS et al

product- and sports- and/or activity- transferred to another hospital, or version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary,

related injuries.24 NEISS coders at held for observation) and (2) not NC). A sample weight was assigned to

each of the member hospitals review hospitalized (ie, treated and released, each case by the CPSC on the basis of

every ED case with a diagnosis of any examined and released without the inverse probability of selection,

type of injury. The coders update the treatment, or left against medical and weights were used to generate

database daily, recording data on advice). Location of injury was national estimates. Bivariate

patients’ demographics, products grouped into 2 categories (home or comparisons were conducted via Rao-

involved, and disposition. A brief other). On the basis of the most Scott x2 tests, and strength of

narrative describing the incident is common NEISS product codes, association was assessed by using

included. Population estimates from foreign-body product was grouped relative risks (RRs) with 95%

the US Census Bureau were used to into 9 main categories: (1) coins; (2) confidence intervals (CIs). Statistical

determine injury rates per 10 000 toys; (3) jewelry; (4) batteries; (5) significance was assessed by using

children ,6 years of age.25 nails, screws, tacks, or bolts; (6) hair a = .05. Trend significance of the

products; (7) Christmas decorations; rates of FBIs over time was analyzed

Case Selection Criteria (8) kitchen gadgets; and (9) desk via linear regression. All statistical

All NEISS cases involving injuries supplies. Two additional categories analyses accounted for the complex

identified with a diagnosis code of 41 (not specified and multiple products) sampling frame of the NEISS. Data

(signifying an “ingested foreign were also created on the basis of reported in this article are national

object”) among children ,6 years of product codes. estimates unless otherwise specified

age were reviewed (n = 35 957). After as actual unweighted cases. A

The foreign-body products were

a review of a subset of case minimum of 20 actual cases was

further categorized on the basis of the

narratives, case inclusion and required for generation of national

type of object ingested. New variables

exclusion criteria and variable estimates. This study was exempt

were created and coded on the basis

categories were developed. All case from review by the Institutional

of keyword searches and review

narratives were reviewed to confirm Review Board at Nationwide

and interpretation of case narratives.

that the object in question had been Children’s Hospital.

Coin type was subdivided into 5

swallowed or ingested. Cases were

groups: (1) pennies, (2) nickels, (3)

included in the analysis if (1) the

dimes, (4) quarters, and (5) other.

ingested object was within the RESULTS

There were 7 categories for toys: (1)

gastrointestinal tract beyond the

doll pieces, (2) game pieces, (3) balls, Demographics and Overall

mouth and (2) the ingestion was

(4) blocks, (5) marbles, (6) building Ingestion Trends

suspected via the use of the words

sets, and (7) other. Subcategories for

“possible,” “maybe,” and “allegedly” in Between 1995 and 2015, an

jewelry included (1) bracelets, (2)

the case narrative. Any ambiguous estimated 759 074 (95% CI:

earrings, (3) necklaces and/or chains,

cases were reviewed by .1 author, 589 323–928 825) children ,6 years

(4) rings, and (5) other. Batteries

and disagreements were resolved via of age sought care in US EDs for

were subdivided into the following

consensus. Cases that involved (1) suspected or confirmed FBIs

categories: (1) button (eg, small or

ingestions of foods or liquids, (2) the (Table 1). The number of estimated

disc batteries), (2) AA, (3) AAA, and

location of the object in the airway or cases increased by 93.3% from 1995,

(4) other. The category of nails,

mouth, (3) aspiration, or (4) when there were 22 206 ingestions,

screws, tacks, or bolts had 8

“choking” (unless specified as having to 2015, when there were 42 928. The

subcategories: (1) nails, (2) tacks

resulted in an ingestion) were rate of FBIs per 10 000 US children

and/or push pins, (3) bolts, (4)

excluded (n = 6063), as were case ,6 years of age increased by 91.5%

screws, (5) hooks, (6) nuts, (7)

fatalities (n = 1). The final number of over the study period, from 9.4 cases

washers, and (8) other. Magnet

actual cases used in the analysis was per 10 000 children in 1995 to 17.9 in

ingestion was coded separately as (1)

29 893. 2015 (R2 = 0.90; P , .001; Fig 1).

1 or (2) multiple magnets. If magnet

FBIs most frequently involved

Variables ingestion was not discussed in the

children 1 year of age (21.3%) and

case narrative, the number of

The following variables provided by boys (52.9%). Coins accounted for

magnets was set to missing.

the NEISS were coded into categorical most of the objects ingested (61.7%).

variables. Patient age was categorized Of patients, 10.3% were hospitalized

into 6 groups (,1, 1, 2, 3, 4, and Statistical Analyses (Table 2). Of the 58.7% of cases for

5 years of age). Disposition was Data were analyzed by using SPSS which location was available, 97.2%

regrouped into 2 categories: (1) version 21 (IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM of ingestions occurred within

hospitalized (ie, admitted, treated and Corporation, Armonk, NY) and SAS the home.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on March 5, 2020

PEDIATRICS Volume 143, number 5, May 2019 3

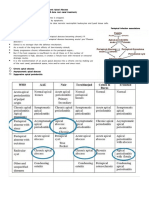

TABLE 1 Characteristics of FBIs Evaluated in US EDs Among Children ,6 Years of Age, 1995–2015 2008 (R2 = 0.90; P = .004), declined

Characteristic No. Estimated 95% CI from 2008 to 2011 (R2 = 0.96;

Actual National Estimate (%)a P = .020), and again increased from

2011 to 2015 (R2 = 0.97; P = .002;

Total 29 893 759 074 589 323–928 825

Sex Fig 3). The percentage of all FBIs that

Male 15 860 401 908 (52.9) 310 256–493 561 involved toys or toy parts remained

Female 14 033 357 165 (47.1) 278 461–435 870 stable over the study period (12.0%

Age, y in both 1995 and 2015). Three-year-

,1 3458 81 930 (10.8) 61 259–102 601

old children most frequently ingested

1 6479 161 542 (21.3) 123 485–199 600

2 5889 154 471 (20.4) 119 909–189 033 toys or toy parts (21.3%), followed by

3 5911 153 291 (20.2) 120 911–185 671 4-year-old children (20.2%). Boys

4 4878 124 070 (16.3) 94 873–153 266 were more likely to ingest toys or toy

5 3278 83 770 (11.0) 64 959–102 581 parts compared with girls (RR: 1.31

Disposition from ED

[95% CI: 1.19–1.44]). When the type

Hospitalizedb 4137 78 302 (10.3) 62 679–93 926

Not hospitalizedc 25 726 679 934 (89.7) 522 886–836 981 of toy could be determined, marbles

Location were most frequently ingested

Homed 17 011 463 717 (97.2) 349 693–577 741 (47.4%).

Othere 541 13 450 (2.8) 10 317–16 583

Foreign-body product

Coins 18 699 468 575 (61.7) 365 408–571 742 Jewelry

Toys 2868 78 544 (10.3) 58 559–98 529

Jewelry 2066 53 459 (7.0) 41 312–65 606 A total of 7.0% of patients ingested

Batteries 2148 51 477 (6.8) 37 121–65 833 jewelry. The rate of jewelry

Nails, screws, tacks, or bolts 1730 48 149 (6.3) 37 321–58 978 ingestions increased from 0.7 cases

Hair products 699 16 109 (2.1) 11 560–20 658

per 10 000 children in 1995 to 1.5 in

Christmas decorations 564 14 896 (2.0) 11 207–18 586

Kitchen gadgets 543 13 191 (1.7) 9075–17 307 2015 (R2 = 0.54; P , .001; Fig 3).

Desk supplies 493 12 909 (1.7) 9430–16 388 Girls were 2.5 times as likely to

Not specified 61 1228 (0.2) 598–1859 ingest jewelry when compared with

Multiple products 22 536 (0.1) 144–927 boys (95% CI: 2.22–2.81). Children

No. magnetsf

#1 year of age accounted for 46.8%

1 576 14 696 (86.7) 10 895–18 497

.1 114 2256 (13.3) 1342–3170 of jewelry ingestions. Earrings

a

comprised 33.7% of jewelry

Some categories do not total 100% because of rounding.

b “Hospitalized” includes admitted, treated and transferred to another hospital, or held for observation. ingestions when the type of jewelry

c “Not hospitalized” includes treated and released, examined and released without treatment, or left against medical

could be determined.

advice.

d “Home” includes manufactured or mobile home, farm, and apartment or condominium.

e “Other” includes industrial place, school, sports or recreation place, and other public property.

f The presence of magnets was determined via interpretation of case narratives. Magnet ingestions represented just 2.2% Batteries

of cases. If a child ingested a magnet, it was then determined if $1 magnet was ingested.

A total of 6.8% of children ingested

batteries. The rate of battery

Coins quarters (16.0%) were the most ingestions increased from 0.01 cases

The rate of coin ingestions increased common. Quarter ingestions per 10 000 children in 1995 to 1.5 in

from 6.3 cases per 10 000 children in increased with age, from 4.4% of 2015, with a peak rate of 2.2 cases in

1995 to 10.5 in 2015, with a peak children ,1 year of age to 21.9% of 2013 (R2 = 0.89; P , .001; Fig 3).

rate of 12.1 cases in 2011 (R2 = 0.74; children 5 years of age. Children who Battery ingestions represented 0.14%

P , .001; Fig 2). Coins accounted for ingested quarters were almost twice of all FBIs in 1995 and 8.4% in 2015.

67.0% of all FBIs in 1995 and 58.5% as likely to be hospitalized when Batteries were most frequently

of ingestions in 2015. Of all patients compared with those who ingested ingested by children who were 1 year

who were hospitalized over the study other coins (RR: 1.87 [95% CI: of age (33.2%). Batteries were the

period, 79.7% ingested coins. When 1.62–2.12]), and children who second most common foreign-body

compared with children who ingested ingested pennies were less likely to product (6.1%) among all patients

all other products, those who be hospitalized (RR: 0.52 [95% CI: who were hospitalized. Of all patients

ingested coins were 2.43 times as 0.45–0.59]). who ingested batteries, 9.2% were

likely to be hospitalized (95% CI: hospitalized. Of the cases in which the

2.14–2.75). Of the case narratives in Toys type of battery could be determined,

which the type of coin could be The rate of toy and toy-part BBs were most frequently ingested

determined, pennies (65.9%) and ingestions increased from 2003 to (85.9%).

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on March 5, 2020

4 ORSAGH-YENTIS et al

and toys are readily found around the

home. Children in this age group are

prone to putting objects in their

mouths,26,27 enticed by the various

colors, shapes, and sizes of the items

investigated in this study. Children

aged 1 to 3 years accounted for the

majority (61.9%) of all ingestions,

likely related to their developmental

stage and curiosity about their

surroundings.

Overall, this study revealed a 4.4%

annual increase in the rate of FBIs

over the 2 decades. This rate increase

was mirrored in every product

category, although the increases in

coin and battery ingestions were

FIGURE 1 most conspicuous. Although any

Overall rate of FBIs by children ,6 years of age, 1995–2015. inferences made into the increase in

rate of FBIs are speculative, it seems

that the increase is likely

Other Products each represented 1.7% of all

multifactorial. Some of the products

A total of 6.3% of patients ingested ingestions. A total of 2.2% of children

investigated in this study are

nails, screws, tacks, or bolts. Boys were evaluated for suspected magnet

increasingly being used in household

(59.7%) and children 1 year of age ingestion, with 13.3% of them

items or have seen an advent on the

(31.8%) most commonly ingested ingesting .1 magnet. Hospitalization

marketplace. The NEISS is also likely

items in this group. Screws accounted was required for 71.1% of children

capturing more ED ingestions than in

for the majority of these ingestions who ingested multiple magnets.

previous years.

(52.7%) when the type could be

DISCUSSION Coins were the objects most

determined. Hair products

frequently ingested, and children who

represented 2.1% of all ingestions During the 21-year study period,

ingested them were most often

and were more commonly ingested nearly 800 000 children ,6 years of

hospitalized. Our study revealed,

by girls (83.6%). Christmas age were estimated to have sought

however, that the percentage of all

decorations represented 2.0% of all care for FBIs in US EDs (an average of

FBIs represented by coins decreased

ingestions, with children #1 year of 99 children each day). This number

slightly over time. Pennies comprised

age accounting for 75.6% of them. likely reflects the accessibility of

the majority of coin ingestions.

Kitchen gadgets and desk supplies these objects because coins, jewelry,

Previous research revealed that

pennies are the most frequently

TABLE 2 Hospitalization by Product Type for Children ,6 Years of Age Presenting to US EDs for FBIs,

ingested coins, and the percentage of

1995–2015

penny ingestions found in this study

No. Estimated 95% CI is similar to that reported

Actual National previously.15,26,27 Older children were

Estimate (%)a

more likely to ingest quarters,

Total 4119 78 128 63 083–93 172 whereas younger children were more

Coins 3298 62 370 (79.8) 50 240–74 500 likely to ingest smaller coins. That

Batteries 241 4744 (6.1) 3231–6256

Toys 173 3441 (4.4) 2456–4426

younger children disproportionately

Jewelry 141 1359 (2.8) 1359–3073 ingested smaller coins likely reflects

Nails, screws, tacks, or bolts 109 2450 (3.1) 1754–3145 their esophageal anatomic constraints

Hair products 62 1135 (1.5) 585–1685 and ease of swallowing smaller items.

Kitchen gadgets 43 630 (0.8) 306–953 Children ingesting quarters were

Desk supplies 27 692 (0.9) 329–1054

Christmas decorations 22 424 (0.5) 92–755

more frequently hospitalized than

a Some categories do not total 100% because of rounding and the need to exclude any categories in which the total

those ingesting smaller coins. Coins

number of actual cases was ,20. Items with actual frequencies of ,20 are not statistically sound to generate national .23.5 mm (such as the quarter) may

estimates via the NEISS. have difficulty passing the pylorus

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on March 5, 2020

PEDIATRICS Volume 143, number 5, May 2019 5

the increased pressure on

manufacturers to package items

appropriately for children ,3 years

of age. The fact that toy ingestions

again increased after 2011 is more

difficult to reconcile, but it may be

related to the overall trend of

increased FBIs.

The findings of this study reveal how

ingestion patterns differ by sex and

age. Jewelry and hair products were

disproportionately ingested by girls,

presumably because girls have more

access to these items. Boys more

frequently ingested screws and nails.

Children #1 year of age were

considerably more likely to ingest

FIGURE 2

Rate of coin ingestions per 10 000 children ,6 years of age, 1995–2015. Christmas decorations and small

objects such as earrings and screws,

again demonstrating that children

and are more likely to become rapidly through the beginning years

ingest accessible and easy-to-

impacted, particularly in the youngest of this study period, reaching a peak

swallow items.

children.11 in 2008, at which time the CPSIA

went into effect (along with its small Batteries and magnets may have

Toys and toy parts were the second parts ruling). The dramatic decrease represented just 6.8% and 2.2% of all

most frequently ingested objects. in toy ingestions through 2011 is cases, respectively, but they can both

Interestingly, toy ingestions increased likely in part related to the CPSIA and enact considerable damage when

ingested. Although they were only the

fourth most commonly ingested

product, batteries were implicated

second most frequently among

patients who were hospitalized.

Battery ingestions increased rather

dramatically over the study period, as

did their representation among all

FBIs. Previous research from the

Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention revealed a 2.5-fold

increase in such ingestions between

1998 and 2010,5 but our data

revealed a 150-fold increase over the

21-year study period. The advent of

BBs is likely culpable for this

increase. Although such batteries

have been used for nearly 30 years,11

the increase in ingestions is likely

related to their increased use in

electronic devices.28 Furthermore, the

past 3 decades have seen increased

morbidity and mortality resulting

from BB use, likely related to

increased battery diameter and

a move to lithium cells,28 which have

FIGURE 3 longer shelf lives and carry more

Rate of toy, battery, and jewelry ingestions per 10 000 children ,6 years of age, 1995–2015. voltage than previous cells.11 These

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on March 5, 2020

6 ORSAGH-YENTIS et al

batteries can enact more mucosal study period was likely Our study underscores the need

destruction and are more likely to underestimated. Children who for further research and continued

become impacted. Given the potential remained at home, sought care at efforts to prevent such ingestions,

for harm with BB ingestion, the their primary care provider’s office or particularly within the home

American Academy of Pediatrics urgent care, or had unknown environment, where FBIs most

(AAP) designed a task force to ingestions were unlikely to have been commonly occur. Recommendations

develop strategies to decrease these captured in this data set. for prevention of FBIs by both

ingestions.29 Furthermore, we did not include the AAP and NASPGHAN include

During the study period, the vast cases in which caregivers called keeping such products out of

majority of magnet ingestions a poison-control center and were children’s reach, ensuring that

consisted of a single magnet, and advised that evaluation was child-resistant packaging is used,

those patients were likely to be unnecessary. We were unable to and keeping particularly dangerous

discharged after their ingestion. generate national estimates when products off the market.29,33,34

Advocacy efforts continue to be there were ,20 actual cases of Continued education through

focused on the sale of high-powered ingestion of a particular product. the public sphere and primary

magnets. In 2012, the North Because the NEISS is not considered care office is also of supreme

American Society for Pediatric useful for identifying fatalities, we did importance.

Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and not address those that may have

Nutrition (NASPGHAN) surveyed its resulted from FBI in our study. Data

members on neodymium-magnet regarding confirmation of ingestion

ABBREVIATIONS

ingestion and reported its findings to and product type were based on case

narratives and thus subject to errors AAP: American Academy of

the CPSC.30 Later that year, the CPSC

in reporting and interpretation. The Pediatrics

proposed the ban on the production

case narratives do not confer BB: button battery

and sale of magnet sets; magnet

management strategies, sizes of BBs, CI: confidence interval

ingestions decreased thereafter.23,31

or types of magnets, so we were CPSC: Consumer Product Safety

In 2016, the US Court of Appeals for

unable to make inferences on patient Commission

the Tenth Circuit lifted the restriction

outcomes. Despite those limitations, CPSIA: Consumer Product Safety

on the production and sale of high-

this study is strengthened by its 21- Improvement Act

powered magnet sets, and now these

year study period and use of a large ED: emergency department

magnet sets can be sold if marketed

nationally representative sample. FBI: foreign-body ingestion

for purposes other than play.32 Both

NASPGHAN: North American

the AAP and NASPGHAN have alerted Our study results reveal that FBIs in Society for Pediatric

their members to the dangers children ,6 years of age have been Gastroenterology,

inherent in high-powered magnet increasing over the past 2 decades. Hepatology, and

ingestion.33,34 The rise in coin, toy, and jewelry Nutrition

This study has several limitations. ingestions is mirrored by an increase NEISS: National Electronic Injury

Given that the NEISS captures only in ingestions of products such as Surveillance System

the patients who presented to its EDs, batteries, which, when swallowed, RR: relative risk

the total number of FBIs during the have the potential to cause harm.

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

REFERENCES

1. Cheng W, Tam PK. Foreign-body literature. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 4. Gummin DD, Mowry JB, Spyker DA,

ingestion in children: experience with 2016;2016:8520767 Brooks DE, Fraser MO, Banner W.

1,265 cases. J Pediatr Surg. 1999; 2016 annual report of the American

34(10):1472–1476 3. Litovitz TL, Klein-Schwartz W, White S,

et al. 2000 annual report of the Association of Poison Control

2. Bekkerman M, Sachdev AH, Andrade J, American Association of Poison Control Centers’ National Poison Data

Twersky Y, Iqbal S. Endoscopic Centers Toxic Exposure Surveillance System (NPDS): 34th annual report.

management of foreign bodies in the System. Am J Emerg Med. 2001;19(5): Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017;55(10):

gastrointestinal tract: a review of the 337–395 1072–1252

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on March 5, 2020

PEDIATRICS Volume 143, number 5, May 2019 7

5. Denney W, Ahmad N, Dillard B, Nowicki 15. Chen X, Milkovich S, Stool D, van As AB, Commission; 2000. Available at: https://

MJ. Children will eat the strangest Reilly J, Rider G. Pediatric coin www.cpsc.gov/Research–Statistics/NEISS-

things: a 10-year retrospective analysis ingestion and aspiration. Int J Pediatr Injury-Data. Accessed March 12, 2018

of foreign body and caustic ingestions Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;70(2):325–329 25. US Census Bureau. Intercensal

from a single academic center. Pediatr 16. Arana A, Hauser B, Hachimi-Idrissi S, estimates of the United States

Emerg Care. 2012;28(8):731–734 Vandenplas Y. Management of ingested population for 1995-2015. 2015.

6. Velitchkov NG, Grigorov GI, Losanoff JE, foreign bodies in childhood and review Available at: www.census.gov. Accessed

Kjossev KT. Ingested foreign bodies of of the literature. Eur J Pediatr. 2001; March 12, 2018

the gastrointestinal tract: retrospective 160(8):468–472 26. Binder L, Anderson WA. Pediatric

analysis of 542 cases. World J Surg. 17. Hanba C, Cox S, Bobian M, et al. gastrointestinal foreign body ingestions.

1996;20(8):1001–1005 Consumer product ingestion and Ann Emerg Med. 1984;13(2):112–117

7. Abbas MI, Oliva-Hemker M, Choi J, et al. aspiration in children: a 15-year review. 27. Paul RI, Christoffel KK, Binns HJ, Jaffe

Magnet ingestions in children Laryngoscope. 2017;127(5):1202–1207 DM. Foreign body ingestions in children:

presenting to US emergency 18. Abraham VM, Gaw CE, Chounthirath T, risk of complication varies with site of

departments, 2002-2011. J Pediatr Smith GA. Toy-related injuries among initial health care contact. Pediatric

Gastroenterol Nutr. 2013;57(1):18–22 children treated in US emergency Practice Research Group. Pediatrics.

departments, 1990-2011. Clin Pediatr 1993;91(1):121–127

8. Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC). Injuries from batteries (Phila). 2015;54(2):127–137 28. Litovitz T, Whitaker N, Clark L, White NC,

among children aged ,13 years–United 19. US Consumer Product Safety Marsolek M. Emerging battery-ingestion

States, 1995-2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Commission. The Consumer Product hazard: clinical implications. Pediatrics.

Wkly Rep. 2012;61(34):661–666 Safety Improvement Act (CPSIA). Available 2010;125(6):1168–1177

at: https://www.cpsc.gov/Regulations- 29. American Academy of Pediatrics. Button

9. Centers for Disease Control and

Laws–Standards/Statutes/The-Consumer- battery task force: the hazards of button

Prevention (CDC). Gastrointestinal

Product-Safety-Improvement-Act. batteries. 2018. Available at: https://

injuries from magnet ingestion in

Accessed March 18, 2018 www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/

children–United States, 2003-2006.

MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006; 20. US Consumer Product Safety aap-health-initiatives/Pages/Button-

55(48):1296–1300 Commission. Small parts for toys and Battery.aspx. Accessed March 21, 2018

children’s products business guidance. 30. North American Society for Pediatric

10. Lee JH, Lee JH, Shim JO, Lee JH, Eun BL,

Available at: https://www.cpsc.gov/ Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and

Yoo KH. Foreign body ingestion in children:

Business–Manufacturing/Business- Nutrition (NASPGHAN). High-powered

should button batteries in the stomach be

Education/Business-Guidance/Small- magnet ingestions by children. In: US

urgently removed? Pediatr Gastroenterol

Parts-for-Toys-and-Childrens-Products. Consumer Product Safety Commission

Hepatol Nutr. 2016;19(1):20–28

Accessed March 17, 2018 Meeting; June 5, 2012; Bethesda, MD

11. Kramer RE, Lerner DG, Lin T, et al; North 21. US Consumer Product Safety Commission. 31. Rosenfield D, Strickland M, Hepburn

American Society for Pediatric CPSC starts rulemaking to develop new CM. After the recall: reexamining

Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and federal standard for hazardous, high- multiple magnet ingestion at a large

Nutrition Endoscopy Committee. powered magnet sets. 2012. Available at: pediatric hospital. J Pediatr. 2017;186:

Management of ingested foreign bodies www.cpsc.gov/en/Newsroom/News- 78–81

in children: a clinical report of the Releases/2012/CPSC-Starts-Rulemaking-to-

NASPGHAN Endoscopy Committee. 32. Zen Magnets, LLC v Consumer Product

Develop-New-Federal-Standard-for-

J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015; Safety Commission, No. 14-9610. (10th

Hazardous-High-Powered-Magnet-Sets/.

60(4):562–574 Cir 2016)

Accessed March 18, 2018

12. Sharpe SJ, Rochette LM, Smith GA. 33. American Academy of Pediatrics. AAP

22. Stevenson TA. Final rule: safety

Pediatric battery-related emergency alerts pediatricians to dangers of

standard for magnet sets. 2014.

department visits in the United States, magnet ingestions. 2018. Available at:

Available at: https://www.regulations.

1990-2009. Pediatrics. 2012;129(6): https://www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-

gov/document?D=CPSC-2012-0050-2596.

1111–1117 and-policy/federal-advocacy/Pages/AAP-

Accessed October 9, 2018

Alerts-Pediatricians-to-Dangers-of-

13. Tavarez MM, Saladino RA, Gaines BA, 23. Reeves PT, Nylund CM, Krishnamurthy J, Magnet-Ingestions.aspx. Accessed

Manole MD. Prevalence, clinical Noel RA, Abbas MI. Trends of magnet March 21, 2018

features and management of pediatric ingestion in children, an ironic 34. North American Society for Pediatric

magnetic foreign body ingestions. attraction. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and

J Emerg Med. 2013;44(1):261–268 2018;66(5):e116–e121 Nutrition. NASPGHAN statement on high-

14. Strickland M, Rosenfield D, Fecteau A. 24. US Consumer Product Safety powered magnet court ruling. 2016.

Magnetic foreign body injuries: a large Commission. National Electronic Injury Available at: https://www.naspghan.org/

pediatric hospital experience. J Pediatr. Surveillance System (NEISS). Bethesda, files/2016/Magnet%20Statement%20No

2014;165(2):332–335 MD: US Consumer Product Safety v%202016.pdf. Accessed March 21, 2018

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on March 5, 2020

8 ORSAGH-YENTIS et al

Foreign-Body Ingestions of Young Children Treated in US Emergency

Departments: 1995−2015

Danielle Orsagh-Yentis, Rebecca J. McAdams, Kristin J. Roberts and Lara B.

McKenzie

Pediatrics 2019;143;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-1988 originally published online April 12, 2019;

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/143/5/e20181988

References This article cites 23 articles, 3 of which you can access for free at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/143/5/e20181988#BIBL

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

following collection(s):

Gastroenterology

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/gastroenterology_sub

Public Health

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/public_health_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

in its entirety can be found online at:

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on March 5, 2020

Foreign-Body Ingestions of Young Children Treated in US Emergency

Departments: 1995−2015

Danielle Orsagh-Yentis, Rebecca J. McAdams, Kristin J. Roberts and Lara B.

McKenzie

Pediatrics 2019;143;

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2018-1988 originally published online April 12, 2019;

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/143/5/e20181988

Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it

has been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by

the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest Point Boulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois,

60007. Copyright © 2019 by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print

ISSN: 1073-0397.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile on March 5, 2020

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Epidemiology: of Neonatal Early-Onset SepsisDocument11 pagesEpidemiology: of Neonatal Early-Onset SepsisMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- HiperBR 22Document21 pagesHiperBR 22CarolNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Bronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Executive Summary of A WorkshopDocument9 pagesBronchopulmonary Dysplasia: Executive Summary of A WorkshopErnestina VolpeNo ratings yet

- Adaptacion NeonatalDocument16 pagesAdaptacion NeonatalINGRID YISEL IDROBO AGREDONo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Adaptacion NeonatalDocument16 pagesAdaptacion NeonatalINGRID YISEL IDROBO AGREDONo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- ERC - Ped Clin NA 2019Document30 pagesERC - Ped Clin NA 2019MeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- European Consensus Guidelines On The%2Document16 pagesEuropean Consensus Guidelines On The%2Marce ColmeneroNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- HIperbilirubinemiaDocument11 pagesHIperbilirubinemiahasna ibadurrahmiNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease - 2018 CrossMarkDocument12 pagesAnemia in Chronic Kidney Disease - 2018 CrossMarkCristian MuñozNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- E20153757 FullDocument9 pagesE20153757 FullClara Sima PongtuluranNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- ERC - Ped Clin NA 2019Document30 pagesERC - Ped Clin NA 2019MeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- European Society For Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines For The Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease - Erratum PDFDocument4 pagesEuropean Society For Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines For The Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease - Erratum PDFMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- ERC - Rev Chil Ped 2012Document11 pagesERC - Rev Chil Ped 2012MeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- European Consensus Guidelines On The%2Document16 pagesEuropean Consensus Guidelines On The%2Marce ColmeneroNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- E20153757 FullDocument9 pagesE20153757 FullClara Sima PongtuluranNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Solar Radiation Is Inversely Associated With Inflammatory Bowel Disease AdmissionsDocument9 pagesSolar Radiation Is Inversely Associated With Inflammatory Bowel Disease AdmissionsMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- Anemia in Chronic Kidney Disease - 2018 CrossMarkDocument12 pagesAnemia in Chronic Kidney Disease - 2018 CrossMarkCristian MuñozNo ratings yet

- Enuresis Nejm PDFDocument8 pagesEnuresis Nejm PDFMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- Foreign Body Ingestion in Pediatric Patients.15 PDFDocument6 pagesForeign Body Ingestion in Pediatric Patients.15 PDFMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- Schneider 2001Document16 pagesSchneider 2001MeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 1 PDFDocument11 pages1 PDFJoeljar Enciso SaraviaNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- Foreign Body Ingestion in Pediatric Patients.15 PDFDocument6 pagesForeign Body Ingestion in Pediatric Patients.15 PDFMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- Foregein CE PDFDocument10 pagesForegein CE PDFMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- WJG 24 2741 PDFDocument27 pagesWJG 24 2741 PDFMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Enuresis Nejm PDFDocument8 pagesEnuresis Nejm PDFMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- NASPGHAN Consensus StatementDocument15 pagesNASPGHAN Consensus StatementZulfikar RamadhanNo ratings yet

- Şahin Hamilçıkan and Emrah Can Critical Congenital Heart Disease Screening With A Pulse Oximetry in Neonates: 2017Document5 pagesŞahin Hamilçıkan and Emrah Can Critical Congenital Heart Disease Screening With A Pulse Oximetry in Neonates: 2017MeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Serial C-Reactive Protein Measurements in Newborn Infants Without Evidence of Early-Onset InfectionDocument7 pagesSerial C-Reactive Protein Measurements in Newborn Infants Without Evidence of Early-Onset InfectionMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- European Society For Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines For The Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease - Erratum PDFDocument4 pagesEuropean Society For Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition Guidelines For The Diagnosis of Coeliac Disease - Erratum PDFMeléndezEscobar PatriciaNo ratings yet

- A Concept-Based Approach To Learning: DevelopmentDocument62 pagesA Concept-Based Approach To Learning: DevelopmentAli Nawaz AyubiNo ratings yet

- The Female Reproductive System: Dr. Emanuel Muro HkmuDocument41 pagesThe Female Reproductive System: Dr. Emanuel Muro HkmuMustafa DadahNo ratings yet

- Reading 7 C TextsDocument3 pagesReading 7 C TextsNyan GyishinNo ratings yet

- C.Systematic ReviewDocument12 pagesC.Systematic ReviewIta ApriliyaniNo ratings yet

- Ocean Quest SSD Trainer Manual 2020Document109 pagesOcean Quest SSD Trainer Manual 2020Carmen LuckNo ratings yet

- CBSE Class 6 Science Components of Food MCQs Set A, Multiple Choice Questions For ScienceDocument4 pagesCBSE Class 6 Science Components of Food MCQs Set A, Multiple Choice Questions For ScienceNinaNo ratings yet

- Accomplishment Report: Municipality of NarvacanDocument3 pagesAccomplishment Report: Municipality of Narvacanuser computerNo ratings yet

- ML SyllDocument2 pagesML Syllmurlak37No ratings yet

- UPSC NDA CDS II CapsuleDocument191 pagesUPSC NDA CDS II CapsulePinaki DuttaNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Principles of Monitoring & Evaluation - NotesDocument113 pagesPrinciples of Monitoring & Evaluation - NotesKeith100% (2)

- Veterinarians 03-2023Document13 pagesVeterinarians 03-2023PRC BaguioNo ratings yet

- APS 305 Activity Sheet WK7Document2 pagesAPS 305 Activity Sheet WK7Ian Jay AlicoNo ratings yet

- Working Conditions of Unorganized Indian WorkersDocument15 pagesWorking Conditions of Unorganized Indian WorkersPiyush DwivediNo ratings yet

- 12 SM 2017 Biology EngDocument206 pages12 SM 2017 Biology EngJaiminGajjar100% (1)

- Curriculum Vitae: Amir E. Ibrahim, M.DDocument11 pagesCurriculum Vitae: Amir E. Ibrahim, M.DkendoNo ratings yet

- Maxillary LandmarksDocument30 pagesMaxillary LandmarksRajsandeep Singh86% (14)

- Histology: Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Apical AbscessDocument3 pagesHistology: Diagnosis and Treatment of Chronic Apical AbscessPrince AmiryNo ratings yet

- Dwnload Full Managment Occupation Health and Safety 5th Edition Kevin Test Bank PDFDocument35 pagesDwnload Full Managment Occupation Health and Safety 5th Edition Kevin Test Bank PDFsinciputlateradiefk7u100% (7)

- Carestation 600 SeriesDocument3 pagesCarestation 600 SeriesABHINANDAN SHARMANo ratings yet

- Improving Project ProposalsDocument2 pagesImproving Project ProposalsNancy Nicasio SanchezNo ratings yet

- Summary Drugrelate SetDocument28 pagesSummary Drugrelate SetthasyaNo ratings yet

- Syllabus Level 1 PDFDocument6 pagesSyllabus Level 1 PDFSwaprakash RoyNo ratings yet

- ReportingDocument4 pagesReportingMark CalimlimNo ratings yet

- Koon-Hung Lee - Choy Lay Fut Kung Fu PDFDocument192 pagesKoon-Hung Lee - Choy Lay Fut Kung Fu PDFjuiz1979100% (3)

- Pediatric Cardiology II Lecture SummaryDocument5 pagesPediatric Cardiology II Lecture SummaryMedisina101No ratings yet

- Chemical Management PolicyDocument9 pagesChemical Management PolicySaifullah SherajiNo ratings yet

- Essentials of Community Medicine - A Practical Approach PDFDocument487 pagesEssentials of Community Medicine - A Practical Approach PDFamarhadid70% (20)

- Using The Vineland 3 On Q Global Pearsonclinical Com AuDocument16 pagesUsing The Vineland 3 On Q Global Pearsonclinical Com AuAndreia SilvaNo ratings yet

- 27 Annual ReportDocument102 pages27 Annual Reportudiptya_papai2007No ratings yet

- Nosotros NoDocument2 pagesNosotros NoAlcindorLeadonNo ratings yet

- Bulletproof Seduction: How to Be the Man That Women Really WantFrom EverandBulletproof Seduction: How to Be the Man That Women Really WantRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (169)

- Wear It Well: Reclaim Your Closet and Rediscover the Joy of Getting DressedFrom EverandWear It Well: Reclaim Your Closet and Rediscover the Joy of Getting DressedRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- 280 Japanese Lace Stitches: A Dictionary of Beautiful Openwork PatternsFrom Everand280 Japanese Lace Stitches: A Dictionary of Beautiful Openwork PatternsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (7)

- Metric Pattern Cutting for Women's WearFrom EverandMetric Pattern Cutting for Women's WearRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- The Ultimate Book of Outfit Formulas: A Stylish Solution to What Should I Wear?From EverandThe Ultimate Book of Outfit Formulas: A Stylish Solution to What Should I Wear?Rating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (23)