Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Review: How Old Is This Fracture? Radiologic Dating of Fractures in Children: A Systematic Review

Uploaded by

signe_paoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Review: How Old Is This Fracture? Radiologic Dating of Fractures in Children: A Systematic Review

Uploaded by

signe_paoCopyright:

Available Formats

Pediatric Imaging

Prosser et al.

Radiologic Dating of Pediatric Fractures

Review

Ingrid Prosser1

Sabine Maguire1

How Old Is This Fracture?

Sara K. Harrison2 Radiologic Dating of Fractures in

Mala Mann3

Jonathan R. Sibert1

Alison M. Kemp1

Children: A Systematic Review

Welsh Child Protection Systematic

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.184:1282-1286.

OBJECTIVE. We conducted a systematic review of the literature to define the evidence

Review Group for radiologic dating of fractures in children in the context of child protection.

Prosser I, Maguire S, Harrison SK, Mann M, Sibert JR, Kemp AM

CONCLUSION. Radiologic dating of fractures is an inexact science. Most radiologists

date fractures on the basis of their personal clinical experience, and the literature provides little

consistent data to act as a resource. There is an urgent need for research to validate the criteria

used in the radiologic dating of fractures in children younger than 5 years.

ractures occur in up to 52% of [10], Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied

F child abuse cases [1, 2]. In con-

trast to accidental fractures, most

abusive fractures occur in chil-

Health Literature (CINAHL) [11], EMBASE [12],

PsychINFO [13], System for Information on Grey

Literature in Europe (SIGLE) [14], Social Science

dren younger than 3 years; 80% of such frac- Citation Index [15], and Turning Research into

tures occur in children younger than 18 Practice (TRIP) [16] databases. In addition, we per-

months [3]. Abusive fractures may be multi- formed an appropriate hand-search of literature pub-

ple and of different ages [4, 5], a point that lished from 1947 to 23rd February 2004. Key words

can only be determined from their dating. used in our search are listed in Appendix 1. Each ar-

Dating fractures may also highlight inconsis- ticle underwent two independent reviews by mem-

tencies between the timing of an injury and bers of a group of 27 specialist reviewers including

the history given, thus aiding in the diagnosis pediatricians, pediatric radiologists, and orthopedic

of child abuse [6]. surgeons, among other child health professionals

Received August 5, 2004; accepted after revision Police and lawyers are particularly interested with expertise in child protection. A third review

September 9, 2004.

in the timing of injuries in child abuse to identify was performed if there was disagreement among the

Supported by the National Society for the Prevention of or exclude potential perpetrators. In the court initial reviewers. We included primary research ad-

Cruelty to Children of the United Kingdom.

setting, radiologists are frequently asked to date dressing the question of radiologically dating frac-

1Department of Child Health, Cardiff University, Wales fractures to narrow down the time of injury. We tures in children younger than 17 years. Studies

College of Medicine, Academic Centre, Llandough

Hospital, Penarth CF64 2XX, Wales, United Kingdom.

have conducted what we believe to be the first were excluded if they were review articles, consen-

Address correspondence to A. M. Kemp. systematic review of the literature to define the sus statements, or expert opinions; if details on chil-

2Department of Radiology, Cardiff University, Wales evidence for radiologic dating of fractures in dren could not be extracted from mixed-age data; if

College of Medicine, Heath Hospital, Heath Park, Cardiff children in the context of child protection. the criteria for dating were not detailed; or if under-

CF14 4XN, Wales, United Kingdom. lying bone disease was present.

3DuthieLibrary, Cardiff University, Wales College of All included studies were analyzed using stan-

Materials and Methods

Medicine, Heath Hospital, Heath Park, Cardiff CF14 4XN, We performed an all-language literature search dardized data extraction and critical appraisal

Wales, United Kingdom.

of original articles published from 1966 through forms [17]. Studies were graded for quality on the

AJR 2005;184:1282–1286

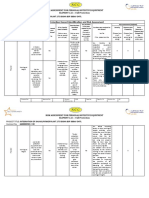

March 2004 as shown in Figure 1. We searched the basis of study design, accurate documentation of

0361–803X/05/1844–1282 Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (AS- the time of injury, and standardized criteria for ra-

© American Roentgen Ray Society SIA) [7], CareData [8], MEDLINE [9], Child Data diologic dating.

1282 AJR:184, April 2005

Radiologic Dating of Pediatric Fractures

Results appear to have been obtained 7 days after the in- calcification of callus; stage 2, callus com-

Figure 1 summarizes the total number of jury. Periosteal reaction was evident in all 33 pa- pletely bridging the fracture; and stage 3,

studies identified and reviewed. Three studies tients imaged 4 weeks after injury. Density smooth, homogeneous mature callus in which

met the criteria for inclusion [18–20], reflect- increased at fracture margins at 2 weeks, with a the fracture line is still visible.

ing data on 189 children, 56 of whom were peak at 4 to 6 weeks in 85% (128/150) of the The third included study, conducted in

younger than 5 years. fractures. No increase in fracture margin sclero- 1979, assessed 23 newborns with fractured

Two studies defined staging criteria (Table sis was seen after 11 weeks. Calcified callus clavicles, humeri, and femurs sustained at

1). Islam et al. [19] examined 707 radiographs (calcified periosteal reaction) was seen as early birth. These were assessed solely for first ap-

of forearm fractures in 141 children randomly as 2 weeks after injury in 15% (18/117) of the pearance of calcification at fracture site. The

selected over a 4-year period; only 23 were fractures and at all fracture sites by 4 weeks. Af- earliest appearance was 7 days after birth;

younger than 5 years. All fractures were im- ter 10 weeks, 90% (26/29) of the calluses had a peak calcification was seen 9–10 days after

mobilized with casts. Fractures treated by density equal to or greater than that of the cor- birth; and the latest appearance was 11 days

surgical fixation were excluded. Patients un- tex. At 8 weeks, 50% of the fractures showed after birth. The numbers included were again

derwent radiography at various times ranging evidence of bridging. The earliest remodeling very small and differed for each fracture. No

from 0 to 100 days after injury. A pediatric ra- was seen at 4 weeks and was noted in 95% (91/ details were offered as to how many radio-

diologist who was unaware of the time inter- 96) from 8 weeks onward. graphs were acquired per child and at what

val after trauma assessed all radiographs. The Yeo and Reed [20] also defined criteria with time intervals.

study defined clear staging criteria that were which to date fractures radiologically, looking

based on data from the radiology and histol- only at callus formation. Patients with solitary Discussion

ogy literature (Table 2). closed nonpathologic fractures of the femoral Despite didactic statements in textbooks as

Using their dating criteria, Islam found that shaft were included. All were treated by traction to the dating of fractures in children, there is

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.184:1282-1286.

periosteal reaction was not observed on any ra- followed by the application of a hip spica cast. a disappointing lack of primary evidence on

diograph obtained before 2 weeks after the in- Radiographs were obtained as clinically indi- which to base dating [21]. Given the high

jury. However, only 22 patients (most with cated at varying time intervals (Table 1). Three prevalence of abusive fractures in infants and

casts) underwent radiography between 7 and 14 stages of callus formation were defined (Table toddlers, and to a lesser extent in preschool

days after the injury. The earliest radiographs 2): stage 1, the earliest radiographically visible children [1, 2, 5, 22–24], it is particularly

worrying that the two larger studies only in-

cluded 33 children in this age group. Other

limitations of the included studies are the

variation of intervals between radiographs

Hand-search of all articles (especially at the early stages of healing) and

MEDLINE 1966–2004

CareData 1970–2004

Hand-search of text books identified from other sources the different numbers of radiographs per frac-

EMBASE 1980–2004 ture (Table 1). The presence of casts, un-

SIGLE 1980–2004

Social Sciences Citation 1981–2004 avoidably, impaired the detection of subtle

CINAHL

ASSIA

1982–2004

1987–2004

radiographic signs. In addition, Yeo and Reed

ISI Proceedings 1990–2004 [20] and Islam et al. [19] chose different bones

Child Data 1996–2004

TRIP database 1997–2004 to study, femur and forearm, respectively,

which may have different healing rates, but

published evidence is lacking in this area.

Radiologists usually determine the age of

fractures based on clinical experience and

guidance offered in textbooks [21]. Unfortu-

Scanned total 1,556 titles and abstracts for duplicates and relevancy

nately the terms describing the phases of heal-

ing differ between the two included studies

that offer criteria [19, 20], and these differ

from the terminology in Kleinman’s textbook

[21] (Table 3). The table in this often-quoted

399 reviewed

source is derived from the personal clinical

Third Review

experience of the authors and has not been

Translated

146 22 further validated by any primary research (J. F.

O’Connor, personal communication, June

2004). It is impossible to assess whether the

three sets of criteria are in agreement as to the

Included in analysis

3

peak times at which phases of healing occur. A

radiologist who regularly reports trauma radio-

graphs, with a documented history for time of

injury, can develop expertise in this area over

Fig. 1.—Chart displays our search strategy for articles on radiologic dating of fractures in children. time. However, because the criteria are not

AJR:184, April 2005 1283

Prosser et al.

TABLE 1 Key Features of Included Studies

Mean No. of

Total No. of

Radiographs Number and Site

Author (year) Study Type Children Age Range Association of Healing With Age/Sex

per Child of Fractures

(no. < 5 yr)

(range)

Islam 2000 [19] Longitudinal 141 (23) 3.7 (2–8) 1–17 years (mean, 8 yr) No association (chi square) 131 fractured radii,

74 fractured ulnae

Yeo 1994 [20] Longitudinal 25 (10) 9 (6–17) Birth–14 yr No association (multiple regression analysis and 25 fractured femora

Student's t test)

Cumming 1979 Longitudinal 23 (23) 1 Birth–11 days N/A 10 clavicles, 6 humeri,

[18] 7 femora

Note.—N/A = not applicable.

standardized or reproducible, less experienced after injury and was present in 50% by 4 weeks. studies are needed to assess standardized criteria

radiologists have little primary evidence on The variable interval between radiographs in the for dating fractures in children younger than 5

which to base their practice. studies leaves gaps at the most crucial early years.

Despite the conflicting conclusions of the in- stages of healing, and time frames may there- The fractures in these studies were all im-

cluded studies, there is agreement that hard cal- fore be inaccurate. There is universal agreement mobilized, which limits its application to dat-

lus and early remodeling are seen at 8 weeks in that the radiologic features noted are a contin- ing fractures in child abuse. Many abusive

most cases. Early callus was first noted 7 days uum, with considerable overlap. Larger-scale fractures are occult [25, 26], and late presen-

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.184:1282-1286.

tation allows continued movement, further in-

jury and repetitive fracture, further

complicating the dating process. It is frequently

TABLE 2 Radiologic Features of Healing in Three Studies Included in Analysis

stated that fractures heal faster in young chil-

Islam 2000 [19] Yeo 1994 [20] Cumming 1979 [18] dren and especially in infants, but as yet, there

Radiologic Feature Peak Peak Peak is no published radiologic evidence to support

(range) (range) (range)

this statement. It has been noted in adults that

Fracture gap widening 4–6 wk, 56% healing may be faster with coexistent severe

(2–8) head injury. Perkins and Skirving [27] found

Periosteal reaction 4–7 wk, 100% 1.6 wk 9–10 days that the average femoral fracture healing time

(stage 1) (2 wk onward) (1–3 wk) (7–11 days) was 12.4 weeks in those with a head injury

Marginal sclerosis 4–6 wk, 85% versus 15.7 weeks in control subjects (p <

(2–11) 0.00005). A study by Spencer [28] that in-

1st callus 4–7 wk, 100% cluded an age range from 4 to 67 years found

(2 wk onward) almost identical changes: 12.4 weeks in the

Callus density > cortex density 13 wk, 90% group with a head injury versus 15.2 weeks in

( 4 wk onward) the control subjects. Unfortunately, the data

Bridging 13 wk, 50% 2.6 wk for the children were not separated from the

(stage 2) (3 wk onward 10) (1.5–3.7 wk) data for adults, making it impossible to ana-

Periosteal incorporation 14 wk lyze it for this review. This finding may be

(7 wk onward) relevant in the context of nonaccidental head

Remodeling 9 wk 8 wk injury in which fractures coexist in as much as

(stage 3) (4 wk onward) (5–11 wk) 50% of the cases [29].

Pergolizzi and Oestreich [30] highlighted

the importance of familiarity with normal

TABLE 3 Timetable of Radiologic Changes in Children’s Fractures physiologic periosteal reaction in infants

younger than 6 months. These infants may

Category Early Peak Late show symmetric diaphyseal periosteal reac-

Resolution of soft tissues 2–5 days 4–10 days 10–21 days tion, although it may be more prominent on

SPNBF 4–10 days 10–14 days 14–21 days one side [31]. This should not be misinter-

preted as a healing fracture.

Loss of fracture line definition 10–14 days 14–21 days

In 1996, Kleinman et al. [32] mentioned

Soft callus 10–14 days 14–21 days that performing a repeat skeletal survey 2

Hard callus 14–21 days 21–42 days 42–90 days weeks after the initial survey aided in the dat-

Remodeling 3 mo 1 yr 2 yr to physeal closure ing of fractures in 18% (13/70) of children

Note.—Adapted from [21, 35] with permission. Repetitive injuries may prolong categories 1, 2, 5, and 6. SPNBF younger than 3 years. No details were given

= subperiosteal new bone formation. as to what specific features were used for dat-

1284 AJR:184, April 2005

Radiologic Dating of Pediatric Fractures

ing in this study. Bone scans have no place in L. Price, B. Ranton, P. Thomas, E. Webb, 17. National Health Service Centre for Reviews and Dis-

fracture dating because they show positive re- and C. Woolley. semination (CRD). Undertaking systematic reviews of

research on effectiveness: CRD’s guidance for those

sults within 7 hr of injury [33] and can continue

carrying out or commissioning reviews, 2nd ed. York,

to show positive results for as long as 1 year. England: University of York, 2001. CRD report 4

Digital imaging is rapidly replacing stan- 18. Cumming W. Neonatal skeletal fractures: birth

dard techniques in many centers. Although References

trauma or child abuse? J Can Assoc Radiol

1. Kogutt M, Swischuk L, Fagan C. Patterns of in-

Kleinman et al. [34] found these digital tech- jury and significance of uncommon fractures in

1979;30:30–33

niques to be comparable to conventional 19. Islam O, Soboleski D, Symons S, Davidson L,

the battered child syndrome. Am J Roentgenol Ra-

imaging for identifying abusive fractures Ashworth M, Babyn P. Development and dura-

dium Ther Nucl Med 1974;121:143–149

tion of radiographic signs of bone healing in chil-

postmortem in the United States, no assess- 2. Loder R, Bookout C. Fracture patterns in battered

dren. AJR 2000;175:75–78

ment of digital radiologic fracture dating has children. J Orthop Trauma 1991;5:428–433

20. Yeo L, Reed M. Staging of healing of femoral frac-

been performed. The direct digital radiogra- 3. Worlock P, Stower M, Barbor P. Patterns of frac-

tures in children. Can Assoc Radiol J 1994; 45:16–19

tures in accidental and non-accidental injury in chil-

phy system used in the study by Kleinman et 21. Kleinman PK, ed. Diagnostic imaging of child

dren: a comparative study. BMJ 1986;293:100–102

al. differs from the computed digital radiogra- 4. Duhaime A, Alario A, Lewander W, et al. Head

abuse, 2nd ed. St Louis, MO: Mosby, 1998

phy system more widely used in the United 22. Merten D, Kirks D, Ruderman R. Occult humeral

injury in very young children: mechanisms, injury

epiphyseal fracture in battered infants. Pediatr

Kingdom. Studies are urgently required to types, and ophthalmologic findings in 100 hospi-

Radiol 1981;10:151–154

validate dating using both systems if this is to talized patients younger than 2 years of age. Pedi-

23. Merten D, Radlowski M, Leonidas J. The abused

become standard practice. atrics 1992;90:179–185

child: a radiological reappraisal. Radiology

5. Leventhal J, Thomas S, Rosenfield N, Markowitz

In conclusion, our analysis showed that the 1983;146:377–381

R. Fractures in young children. Distinguishing

evidence base for current methods of radio- child abuse from unintentional injuries. Am J Dis

24. McMahon P, Grossman W, Gaffney M, Stanitski

logic dating is sparse. Dating of fractures in C. Soft-tissue injury as an indication of child

Child 1993;147:87–92

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.184:1282-1286.

children is an inexact science. The radiologic abuse. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:1179–1183

6. Kleinman P, Blackbourne B, Marks S, Karellas A,

25. Smith F, Gilday D, Ash J, Green M. Unsuspected

features of bone healing are a continuum, Belanger P. Radiologic contributions to the inves-

costo-vertebral fractures demonstrated by bone

with considerable overlap. Radiologic esti- tigation and prosecution of cases of fatal infant

scanning in the child abuse syndrome. Pediatr Ra-

mates of the time of injury are made in terms abuse. N Engl J Med 1989;320:507–511

diol 1980;10:103–106

7. Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (AS-

of weeks rather than days. It is vital for all in- SIA) [database online]. East Grinstead, West Sus- 26. Sty J, Starshak R. The role of bone scintigraphy in

vestigating agencies to be aware of these sex, England: Cambridge Scientific Abstracts. the evaluation of the suspected abused child. Ra-

broad time frames. However, radiologists can Updated February 23, 2004 diology 1983;146:369–375

clearly differentiate recent from old fractures. 8. CareData [database online]. London, England: 27. Perkins R, Skirving A. Callus formation and the rate

Social Care Institute for Excellence. Updated of healing of femoral fractures in patients with head

Such differentiation remains valuable in iden-

February 23, 2004 injuries. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987; 69:521–524

tifying a child who has been subjected to re- 28. Spencer R. The effect of head injury on fracture

9. MEDLINE [database online]. Bethesda, MD: Na-

peated abuse or whose injuries are thus shown healing: a quantitative assessment. J Bone Joint

tional Library of Medicine, U.S. National Insti-

to be inconsistent with the history offered. tutes of Health. Updated February 23, 2004 Surg Br 1987;69:525–528

Our findings have the following four im- 10. National Children’s Bureau Database [database 29. Kemp A, Stoodley N, Cobley C, Coles L, Kemp

plications for practice: the dating of fractures online]. Updated February 23, 2004 K. Apnoea and brain swelling in non-accidental

in children is an inexact science; clinicians 11. Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Lit- head injury. Arch Dis Child 2003;88:472–476

erature (CINAHL) [database online]. San Francisco, 30. Pergolizzi RJ, Oestreich A. Child abuse fracture

must bear this fact in mind when offering time

CA: Galen Digital Library of the University of Cal- through physiologic periosteal reaction. Pediatr

frames of injuries to investigating agencies or Radiol 1995;25:566–567

ifornia–San Francisco. Updated February 23, 2004

courts; periosteal reaction is seen as early as 12. EMBASE [database online]. Philadelphia, PA: 31. Shopfner C. Periosteal bone growth in normal in-

4 days and is present in at least 50% of the Elsevier. Updated February 23, 2004 fants: a preliminary report. AJR 1966;97:154–163

cases by 2 weeks after the injury; and remod- 13. PsychINFO [database online]. Washington, DC: 32. Kleinman PK, Nimkin K, Spevak MR, et al. Fol-

eling peaks 8 weeks after injury. American Psychological Association. Updated low-up skeletal surveys in suspected child abuse.

February 23, 2004 AJR 1996;167:893–896

14. System for Information on Grey Literature in Eu- 33. Rosenthall L, Hill R, Chuang S. Observation on

Acknowledgments rope (SIGLE) [database online]. The Hague. The the use of 99mTc-phosphate imaging in periph-

We thank our panel of expert reviewers, Netherlands: European Association for Grey Lit- eral bone trauma. Radiology 1976;119:637–641

the Welsh Child Protection Systematic Re- erature. Updated February 23, 2004 34. Kleinman PK, O’Connor B, Nimkin K, et al. De-

15. Social Science Citation Index [database online]. tection of rib fractures in an abused infant using

view Group: M. Barber, P. Barnes, M.

Philadelphia, PA: Thomson Scientific. Updated digital radiography: a laboratory study. Pediatr

Bhal, J. Bowen, R. Brooks, A. Butler, S. February 23, 2004 Radiol 2002;32:896–901

Datta, R. Frost, C. Graham, M. James-El- 16. Turning Research into Practice (TRIP) Database 35. O’Connor J, Cohen J. Dating fractures. In: Klein-

lison, N. John, A. Maddocks, S. Morris, A. Plus [database online]. London, England: TRIP man PK, ed. Diagnostic imaging of child abuse.

Mott, A. Naughton, C. Norton, H. Payne, Database Ltd. Updated February 23, 2004 St. Louis, MO: Mosby, 1998:168–177

Appendix 1 appears on next page

AJR:184, April 2005 1285

Prosser et al.

APPENDIX 1. Keywords and Phrases Used for the Fracture Dating Review

1. child abuse.mp. 21. (corner fractur: or bucket handle fractur:).mp.

2. child protection.mp. 22. metaphyseal chip fractur:.mp.

3. (battered child or shaken baby or battered baby).mp. 23. classic metaphyseal lesion:.mp.

4. 1 or 2 or 3 24. or/13-23

5. child:.mp. 25. (investigat: adj3 fract:).mp.

6. non-accidental injur.mp. 26. (radiolog: adj3 fractur:).mp.

7. non-accidental trauma.mp. 27. (roentgen: adj3 fract:).mp.

8. (non-accidental: and injur:).mp. 28. skeletal survey.mp.

9. soft tissue injur:.mp. 29. bone scan:.mp.

10. physical abuse.mp. 30. Isotope Bone Scan:.mp.

11. (or/6-10) and 5 31. Radionuclide.mp.

12. 4 or 11 32. Scintigraphy.mp.

13. fractur:.mp. 33. ((paediatric or pediatric) adj3 radiolog:).mp.

14. rib fractur:.mp. 34. ((paediatric or pediatric) adj3 nuclear medicine).mp.

15. skull fractur:.mp. 35. (ag: adj3 fractur:).mp.

16. femoral fractur:.mp. 36. ((dating or date) adj3 fractur:).mp.

17. humeral fractur:.mp. 37. (pattern: adj3 fractur:).mp.

18. pelvic fractur:.mp. 38. (heal: adj3 fractur:).mp.

19. spiral fractur:.mp. 39. (timing adj3 healing).mp.

20. metaphyseal fractur:.mp.

American Journal of Roentgenology 2005.184:1282-1286.

1286 AJR:184, April 2005

You might also like

- 2 - Civil Liberties Union Vs Executive SecretaryDocument3 pages2 - Civil Liberties Union Vs Executive SecretaryTew BaquialNo ratings yet

- Oil and Gas CompaniesDocument4 pagesOil and Gas CompaniesB.r. SridharReddy0% (1)

- CF34-10E LM June 09 Print PDFDocument301 pagesCF34-10E LM June 09 Print PDFPiipe780% (5)

- As 2419Document93 pagesAs 2419Craftychemist100% (2)

- Prince SopDocument3 pagesPrince Sopvikram toorNo ratings yet

- Bird Nest Article in PressDocument10 pagesBird Nest Article in PressAnonymous fR07oTXb100% (1)

- Error Codes & Diagram DCF80-100Document247 pagesError Codes & Diagram DCF80-100Dat100% (1)

- Newtom 3G ManualDocument154 pagesNewtom 3G ManualJorge JuniorNo ratings yet

- Main - Iwata Et Al 1982Document18 pagesMain - Iwata Et Al 1982TimiNo ratings yet

- Pravin Raut Sanjay Raut V EDDocument122 pagesPravin Raut Sanjay Raut V EDSandeep DashNo ratings yet

- The Added Value of A Second Read by Pediatric Radiologists For OutsideDocument7 pagesThe Added Value of A Second Read by Pediatric Radiologists For OutsideSkander GharbiNo ratings yet

- The Epidemiology of Fractures in Otherwise Healthy Children: Pediatrics (M Leonard and L Ward, Section Editors)Document7 pagesThe Epidemiology of Fractures in Otherwise Healthy Children: Pediatrics (M Leonard and L Ward, Section Editors)anon_634779017No ratings yet

- Bacaan AsdDocument8 pagesBacaan AsdJicko Street HooligansNo ratings yet

- Jurnal PediatricDocument9 pagesJurnal PediatricDian Angraeni WidiastutiNo ratings yet

- Ayoub DM CML Versus Rickets Am J Roentgen 2014Document14 pagesAyoub DM CML Versus Rickets Am J Roentgen 2014api-289577018No ratings yet

- Heritability of The Human CraniofacialDocument13 pagesHeritability of The Human CraniofacialJUAN FONSECANo ratings yet

- Fraser Doh Variability 2023Document9 pagesFraser Doh Variability 2023Lindsey BasyeNo ratings yet

- Early-Onset Basal Cell Carcinoma and Indoor Tanning: A Population-Based StudyDocument9 pagesEarly-Onset Basal Cell Carcinoma and Indoor Tanning: A Population-Based StudyHinami TenukiNo ratings yet

- Systematic Review On Heritability of Craniofacial Characteristics Between The Generations of The FamilyDocument14 pagesSystematic Review On Heritability of Craniofacial Characteristics Between The Generations of The Familyparas.sharmaNo ratings yet

- What Is The Best Age To Circumcise? A Medical and Ethical AnalysisDocument19 pagesWhat Is The Best Age To Circumcise? A Medical and Ethical AnalysisDhani Rinaldi MaulanaNo ratings yet

- Delayed Identification of Pediatric Abuse-Related Fractures: What'S Known On This SubjectDocument9 pagesDelayed Identification of Pediatric Abuse-Related Fractures: What'S Known On This SubjectIlta Nunik AyuningtyasNo ratings yet

- A Practical Approach To Diagnosis of Spinal DysraphismDocument17 pagesA Practical Approach To Diagnosis of Spinal DysraphismSecret AccordNo ratings yet

- Visualización de Hematomas Viejos en NiñosDocument5 pagesVisualización de Hematomas Viejos en NiñosBlady GonzalezNo ratings yet

- RJDavidson CoanHandDocument9 pagesRJDavidson CoanHandStephany MenezesNo ratings yet

- Astigmatism and The Development of Myopia in ChildrenDocument8 pagesAstigmatism and The Development of Myopia in Childrend carlNo ratings yet

- Eye-Tracking Measures in Audiovisual Stimuli in Infants at HighDocument3 pagesEye-Tracking Measures in Audiovisual Stimuli in Infants at HighAlejandro BejaranoNo ratings yet

- A Natureza Do Fator Humano Na Paralisia Infantil. I. Pecularidades de Crescimento e DesenvolvimentoDocument8 pagesA Natureza Do Fator Humano Na Paralisia Infantil. I. Pecularidades de Crescimento e DesenvolvimentoKelly AssisNo ratings yet

- Composition Measures by Dual-Energy X-Ray AbsorptiometryDocument9 pagesComposition Measures by Dual-Energy X-Ray AbsorptiometryDhones AndradeNo ratings yet

- Illicit Psychoactive Substance Use, Heavy Use, Abuse, and Dependence in A US Population-Based Sample of Male TwinsDocument9 pagesIllicit Psychoactive Substance Use, Heavy Use, Abuse, and Dependence in A US Population-Based Sample of Male TwinsyuriNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S0165178116302785 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S0165178116302785 MainJohn TelekNo ratings yet

- Carolina Marpaung - Maurits K. A. Van Selms - Frank LobbezooDocument8 pagesCarolina Marpaung - Maurits K. A. Van Selms - Frank LobbezooMarco Saavedra BurgosNo ratings yet

- Brain and Behavior - 2019 - Li - A Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study of Brain Microstructural Changes Related To Religion andDocument13 pagesBrain and Behavior - 2019 - Li - A Diffusion Tensor Imaging Study of Brain Microstructural Changes Related To Religion andR MashNo ratings yet

- Sharda 2019Document3 pagesSharda 2019Lilian Elisa HernándezNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Bruxism: From Etiology To Treatment: A ReviewDocument4 pagesPediatric Bruxism: From Etiology To Treatment: A ReviewApurava SinghNo ratings yet

- Rollerblading and Skateboarding Injuries in Children Northeast EnglandDocument3 pagesRollerblading and Skateboarding Injuries in Children Northeast EnglandblllllllllahNo ratings yet

- Insecure Attachment in Severely Asthmatic Preschool ChildrenDocument5 pagesInsecure Attachment in Severely Asthmatic Preschool ChildrenMatt Van VelsenNo ratings yet

- A Video-Based Measure To Identify Autism Risk in InfancyDocument7 pagesA Video-Based Measure To Identify Autism Risk in InfancyZachNo ratings yet

- 385 FullDocument6 pages385 Fullila chaeruniNo ratings yet

- MRI Findings in Prematurely Born Adolescents and YDocument3 pagesMRI Findings in Prematurely Born Adolescents and YGiska VelindaNo ratings yet

- 1 Human Adult Neurogenesis - Evidence and Remaining QuestionsDocument6 pages1 Human Adult Neurogenesis - Evidence and Remaining Questionsmaria svenssonNo ratings yet

- Gabie Et Al. 1997Document10 pagesGabie Et Al. 1997thaiane_machadoNo ratings yet

- Ignelzi 11 04Document7 pagesIgnelzi 11 04andreNo ratings yet

- Daniels Et Al (2015) 508Document9 pagesDaniels Et Al (2015) 508Forum PompieriiNo ratings yet

- Harlow59 PDFDocument12 pagesHarlow59 PDFJuan Carcausto100% (1)

- Spinal Cord Injury in The Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureDocument14 pagesSpinal Cord Injury in The Pediatric Population: A Systematic Review of The LiteratureDana DumitruNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of Stuttering in The Community Across The Entire Life SpanDocument9 pagesEpidemiology of Stuttering in The Community Across The Entire Life SpanDai ArhexNo ratings yet

- Personality and Individual Di Fferences: SciencedirectDocument10 pagesPersonality and Individual Di Fferences: SciencedirectMrWaratahsNo ratings yet

- On Error Management: Lessons From Aviation: Education and DebateDocument5 pagesOn Error Management: Lessons From Aviation: Education and DebatewaynepunkNo ratings yet

- The Infant Disorganised Attachment Classification Patt 2018 Social ScienceDocument7 pagesThe Infant Disorganised Attachment Classification Patt 2018 Social Sciencenafisatmuhammed452No ratings yet

- Cassina 2019Document6 pagesCassina 2019dewaprasatyaNo ratings yet

- Widiger 1991Document7 pagesWidiger 1991Ekatterina DavilaNo ratings yet

- Theepidemiology Ofdistalradius Fractures: Kate W. Nellans,, Evan Kowalski,, Kevin C. ChungDocument13 pagesTheepidemiology Ofdistalradius Fractures: Kate W. Nellans,, Evan Kowalski,, Kevin C. Chungreza rivaldy azaNo ratings yet

- 2014 Revisión Sistemática de Columna en Sujetos Asintomáticos PediátricosDocument6 pages2014 Revisión Sistemática de Columna en Sujetos Asintomáticos PediátricosAnyela Gineth Chisaca NieblesNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of Morbid Curiosity - Development and Initial Validation of The Morbid Curiosity ScaleDocument10 pagesThe Psychology of Morbid Curiosity - Development and Initial Validation of The Morbid Curiosity Scale畏No ratings yet

- Re-Identification of Individuals in Genomic Datasets Using Public Face ImagesDocument10 pagesRe-Identification of Individuals in Genomic Datasets Using Public Face ImagesAnahí TessaNo ratings yet

- Restricted and Repetitive Behaviors in A PDFDocument32 pagesRestricted and Repetitive Behaviors in A PDFusernarcisaNo ratings yet

- J Ijom 2020 06 020-2Document6 pagesJ Ijom 2020 06 020-2quajeutterugrau-6658No ratings yet

- Genetic Studies of Autism: From The 1970s Into The MillenniumDocument12 pagesGenetic Studies of Autism: From The 1970s Into The MillenniumVanessa Llantoy ParraNo ratings yet

- Mulroy 2011Document6 pagesMulroy 2011nugra raturandangNo ratings yet

- Prevalence and Causes of Paralysis-United States, 2013: ResultsDocument6 pagesPrevalence and Causes of Paralysis-United States, 2013: ResultskiranNo ratings yet

- Bite Marks 4Document4 pagesBite Marks 4nocturn 3No ratings yet

- The Salience Network: A Neural System For Perceiving and Responding To Homeostatic DemandsDocument5 pagesThe Salience Network: A Neural System For Perceiving and Responding To Homeostatic DemandsGollapudi SHANKARNo ratings yet

- Capitulo Riesgo FletcherDocument19 pagesCapitulo Riesgo FletcherAnita MacdanielNo ratings yet

- Updating Beliefs Under Perceived Threat: Behavioral/CognitiveDocument11 pagesUpdating Beliefs Under Perceived Threat: Behavioral/CognitiveNenad MilosevicNo ratings yet

- Maggio 2016Document27 pagesMaggio 2016Naty BmNo ratings yet

- Cancer Risks From CT Radiation Is There ADocument3 pagesCancer Risks From CT Radiation Is There AMiguel Marcio Ortuño Mejia0% (1)

- Deep Learning For Chest X-Ray Analysis: A Survey: A A A A ADocument33 pagesDeep Learning For Chest X-Ray Analysis: A Survey: A A A A Amayank kumarNo ratings yet

- 1706181087812Document20 pages1706181087812maheshmonu9449No ratings yet

- GTA Liberty City Stories CheatsDocument6 pagesGTA Liberty City Stories CheatsHubbak KhanNo ratings yet

- Purchase Invoicing Guide AuDocument17 pagesPurchase Invoicing Guide AuYash VasudevaNo ratings yet

- In-N-Out vs. DoorDashDocument16 pagesIn-N-Out vs. DoorDashEaterNo ratings yet

- CorpDocument14 pagesCorpIELTSNo ratings yet

- Grundfosliterature 3081153Document120 pagesGrundfosliterature 3081153Cristian RinconNo ratings yet

- 12 Problem Solving Involving ProportionDocument11 pages12 Problem Solving Involving ProportionKatrina ReyesNo ratings yet

- E-Business & Cyber LawsDocument5 pagesE-Business & Cyber LawsHARSHIT KUMARNo ratings yet

- Mulberry VarietiesDocument24 pagesMulberry VarietiesKUNTAMALLA SUJATHANo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence and Applications: Anuj Gupta, Ankur BhadauriaDocument8 pagesArtificial Intelligence and Applications: Anuj Gupta, Ankur BhadauriaAnuj GuptaNo ratings yet

- CSS Practical No. 14. Roll No. 32Document25 pagesCSS Practical No. 14. Roll No. 32CM5I53Umeidhasan ShaikhNo ratings yet

- FDD SRM & NDGDocument3 pagesFDD SRM & NDGEnd EndNo ratings yet

- JavaDocument14 pagesJavaGANESH REDDYNo ratings yet

- Python Lab10 Report SummaryDocument8 pagesPython Lab10 Report SummaryVivekananda ParamahamsaNo ratings yet

- SDN5025 GREEN DC Electrical Inspection and Test Certificate V1.1Document11 pagesSDN5025 GREEN DC Electrical Inspection and Test Certificate V1.1JohnNo ratings yet

- 2.21 - Hazard Identification Form - Fall ProtectionDocument3 pages2.21 - Hazard Identification Form - Fall ProtectionSn AhsanNo ratings yet

- Summer Training Project (Completed)Document89 pagesSummer Training Project (Completed)yogeshjoshi362No ratings yet

- Axe FX II Tone Match ManualDocument6 pagesAxe FX II Tone Match Manualsteven monacoNo ratings yet

- GMD 15 3161 2022Document22 pagesGMD 15 3161 2022Matija LozicNo ratings yet

- Office of The Sangguniang Panlalawigan: Hon. Francisco Emmanuel "Pacoy" R. Ortega IiiDocument5 pagesOffice of The Sangguniang Panlalawigan: Hon. Francisco Emmanuel "Pacoy" R. Ortega IiiJane Tadina FloresNo ratings yet

- Con Law Koppelman HugeDocument203 pagesCon Law Koppelman HugemrstudynowNo ratings yet

- 5c X-Tend FG Filter InstallationDocument1 page5c X-Tend FG Filter Installationfmk342112100% (1)