Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Fractures of The Posterior Wall of The Acetabulum

Uploaded by

JayOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Fractures of The Posterior Wall of The Acetabulum

Uploaded by

JayCopyright:

Available Formats

Fractures of the Posterior Wall of the Acetabulum

Michael R. Baumgaertner, MD

Abstract

Only 30% of posterior-wall acetabular fractures involve a single large frag- Etiology

ment. The majority are multifragmentary or have areas of impaction.

Unsatisfactory clinical results occur in more than 80% of patients treated non- Most fractures are the result of the

surgically. Operative management usually offers the best chance of preserving sudden deceleration of an unre-

long-term joint function, but only if an anatomically reconstructed acetabulum strained occupant during a motor

can be achieved without complication. The keys to surgical success include vehicle crash. Force is transmitted

maintaining the viability of the fracture fragments and the femoral head itself, from the floorboard to the foot or

using bone grafts and buttress plating to support elevated and comminuted from the dashboard to the flexed

fragments, and protecting the neurovascular structures at risk. Complications knee through the femur to the

can include sciatic nerve injury (incidence, 3% to 18%), heterotopic ossification femoral head. With the hip flexed

(7% to 20%), and osteonecrosis of the femoral head (5% to 8%). Despite the and in varying degrees of adduc-

relative simplicity of this acetabular fracture, unsatisfactory outcomes after sur- tion and internal rotation, as the

gical repair of the posterior wall occur in at least 18% to 32% of cases, results femoral head dislocates, it fractures

that are worse than for most of the other more complex acetabular fracture pat- the posterior wall. The specific

terns. location of the fracture can be pre-

J Am Acad Orthop Surg 1999;7:54-65 dicted from the position of the

extremity at impact. 1 Generally,

the shape of the acetabular fracture

made by the femoral head is an arc

Of all types of acetabular fractures, early open reduction and internal of varying size with a radius of cur-

the posterior-wall fracture is the fixation.2 A recent study reported vature that approximates that of

most common and the seemingly a 30% failure rate within the first the head.

easiest to treat. In LetournelÕs series year after fixation.3 Letournel1 and Because of the indirect nature of

of 940 acetabular fractures, 24% Matta4 achieved perfectly anatomic the fracturing force, it is unusual to

were isolated posterior-wall frac- reductions of posterior-wall acetab- see significant direct soft-tissue

tures, and another 26% involved a ular fractures in 94% to 100% of injury in the area of the hip, but

fracture of the posterior wall as part their cases, and they have indepen- associated injuries to the extremity

of a more complex fracture pattern.1 dently demonstrated that residual are common. Major knee ligament

The familiarity of the posterior displacements greater than only 1

approach to the hip and the simplic- mm after fixation of most types of

ity of the fracture pattern lead many acetabular fractures are associated

surgeons to treat posterior-wall with clinically significant joint Dr. Baumgaertner is Associate Professor and

Chief of the Orthopaedic Trauma Service,

fractures when they might other- deterioration when patients are Department of Orthopaedics and Rehabili-

wise refer more complicated acetab- assessed at long-term follow-up. tation, Yale University, School of Medicine,

ular fractures. The purpose of this article is to New Haven, Conn.

Despite the routine nature of pos- review the assessment and man-

terior-wall fractures, poor outcomes agement of the isolated posterior- Reprint requests: Dr. Baumgaertner, Depart-

occur frequently. In EpsteinÕs long- wall acetabular fracture, emphasiz- ment of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, Yale

University School of Medicine, PO Box

term follow-up of 150 posterior- ing the factors influencing outcome 208701, New Haven, CT 06520.

wall fractures, 88% of patients that the treating physician can con-

treated in a closed manner had an trol. Associated fracture patterns Copyright 1999 by the American Academy of

unsatisfactory result, but so did that involve the posterior wall will Orthopaedic Surgeons.

37% of patients who underwent not be discussed.

54 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Michael R. Baumgaertner, MD

(e.g., posterior cruciate) injuries, tournelÕs classification into a for- bone of the posterior column by the

osteochondral lesions, and foot mat that is consistent with the AO dislocating femoral head, rotating

injuries can be missed unless the Comprehensive Classification of an osteochondral fragment out of

remainder of the extremity is care- Fractures, allowing computerized its anatomic plane. The mecha-

fully assessed. The physician categorizing of posterior-wall frac- nism and resulting joint incongru-

should critically evaluate the status tures.7,8 ency are similar to those seen when

of the sciatic nerve before and after In this system, there are three the lateral femoral condyle creates

attempts at closed reduction. A basic patterns of posterior-wall a split-depression fracture of the

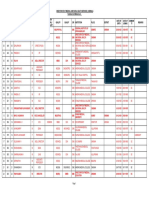

neurologic injury occurs in 18% to fractures (Fig. 1). The simplest pat- tibial plateau. Termed Òmarginal

22% of patients who sustain poste- tern is a fracture line that creates a impactionÓ by Letournel 1 and

rior-wall fracture-dislocations. 1,5 single posterior fragment. Single- Òacetabular depression fractureÓ by

Awareness and documentation of a fragment posterior-wall fractures Brumback et al,9 this type is report-

motor or sensory deficit (even a occurred in 30% of fractures in ed to occur in approximately one

minor one) avoids postoperative LetournelÕs series.1 They can occur fourth of all posterior-wall frac-

confusion and allows appropriate in the posterosuperior aspect of the tures.

preoperative counseling. joint and involve the roof, or weight- Posterior hip fracture-dislocations

bearing Òdome,Ó of the joint. When cause a spectrum of osseous in-

these fractures occur posteroinferi- juries. The large, isolated single-

Classification orly, they take in a varying amount fragment posterior-wall fracture is

of ischium. relatively uncommon; the surgeon

The posterior-wall fracture is one The second variant is the multi- must expect and be prepared to

of the elementary fracture patterns fragment posterior-wall fracture. anatomically reduce and stabilize

of the acetabular fracture classifica- This pattern is seen in about a third the marked comminution and

tion system proposed by Letournel of cases and can be further classi- impaction of the posterior wall that

and co-workers in 1964.6 Although fied on the basis of the number and is frequently found if the patient is

slightly modified subsequently, location of fragments. to benefit from open treatment.

this system has been validated by The third type of wall fracture is

30 years of observation and has the one considered to be the most

gained virtually universal accep- complex and difficult to treat. In Radiologic Diagnosis

tance by acetabular-fracture sur- addition to a single-fragment or

geons. In an attempt to create a multifragment wall fracture, some The anteroposterior (AP) radio-

unified classification system for all of the articular surface remaining graph of the pelvis is an essential

fractures, the Orthopaedic Trauma medial to the primary fracture line diagnostic test in most blunt-trauma

Association recently codified Le- is impacted into the cancellous evaluation protocols. Provided the

Type 1 Type 2 Type 3

Fig. 1 The three subgroups of posterior-wall fractures. In the first type, a fracture line creates a single posterior fragment. The second

type is a multifragment fracture. The third type (also called a marginal impaction or acetabular depression fracture) is a single-fragment

or multifragment wall fracture in which some of the articular surface medial to the primary fracture line has been impacted into the can-

cellous bone of the posterior column by the dislocating femoral head, rotating the osteochondral fragment out of its anatomic plane.

Vol 7, No 1, January/February 1999 55

Posterior-Wall Acetabular Fractures

film is of good quality, most ace- lying femoral head may make this that no incarcerated fragment is

tabular fractures can be recognized finding subtle. To exclude an asso- preventing complete anatomic

on this view. If the hip has not ciated acetabular fracture that reduction.

been reduced, the wall fragment is includes a fracture of the posterior The obturator oblique view,

usually seen to be displaced with wall, the other landmarks (anterior obtained by rotating the patient 45

the femoral head, and the defect in rim, iliopectineal line, ilioischial degrees onto the unaffected side,

the posterior wall is readily appar- line, tear drop, and acetabular roof) displays the obturator ring as near-

ent (Fig. 2, A). It is impossible to should be confirmed to be intact. ly circular and uncovers the poste-

completely assess a posterior-wall Marginal impaction, if present, can rior aspect of the acetabulum from

fracture on an AP radiograph, but often be recognized on the AP radio- the anterior wall and the femoral

this view is very helpful in exclud- graph as a curved, dense subchon- head. It usually shows the full

ing other fracture patterns. dral line that is out of anatomic extent of the fracture fragment, the

Of the six fundamental radio- position (Fig. 2, B). All radiographic amount of displacement, and the

graphic landmarks of the acetabu- views, but particularly the AP view defect in the acetabulum (Fig. 2, C).

lum described by Letournel,1,6 five (which has the opposite hip for Incarcerated fragments in the ante-

will be seen to be intact and unaf- comparison), should be scrutinized rior aspect of the joint are best seen

fected by an isolated posterior-wall to confirm that a concentric reduc- on this view. The opposite oblique

fracture. Only the posterior rim tion with a normal clear space view (the iliac oblique) is obtained

will be disrupted, although once exists between the femoral head by rotating the patient 45 degrees

the dislocation is reduced, the over- and the remaining acetabulum and onto the side of the fracture. The

A B

Fig. 2 Images of a 37-year-old woman

with a left-hip fracture-dislocation. A, The

hip is dislocated with the femur adducted

and internally rotated. Note the defect in

the posterior acetabular border and the

wall fragment above the displaced femoral

head. B, After closed reduction, a wall

defect remains, and there is evidence of

marginal impaction (arrow) but the

amount of posterior-wall fracture-displace-

ment is not obvious. C, The obturator

oblique radiograph shows the wall frag-

ment clearly. D, Axial CT image demon-

strates significant marginal impaction and

an inadequately reduced wall fracture.

C D

56 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Michael R. Baumgaertner, MD

unbreached borders of the greater identifying posteromedial marginal assessed and documented. Subse-

and lesser sciatic notches confirm impaction in a fragment that is quently, the adequacy of the

that the posterior column is intact, rotated externally. However, supe- reduction and the size and dis-

but the wall fracture is usually rior impaction of the lateral aspect placement of the fragments are

obscured. of the roof, which can occur in the assessed radiographically.9 Abso-

Computed tomography (CT) is plane of the axial CT section, may lute operative indications include

probably the single most valuable be more clearly appreciated on an deteriorating sciatic nerve function

tool in assessing posterior-wall AP radiograph or with CT recon- after attempted closed reduction

acetabular fractures, provided indi- structions. With thin sections, in- and the presence of an incarcerated

vidual images through the joint are creased bone density can be seen fragment that prevents congruent

contiguous and not more than 3 to where impaction into the cancellous reduction of the head to the intact

5 mm thick (Fig. 2, D). It is always bed has occurred (Figs. 2, D; 3, C). acetabulum. Inability to achieve a

helpful to include the contralateral In addition, CT is frequently used closed reduction and the presence

acetabulum for comparison. If to quantify the amount of posterior of a femoral neck fracture are also

closed management is being consid- wall that remains after fracture by absolute indications for open man-

ered, CT scanning utilizing 3-mm allowing comparison of the frac- agement.

overlapping sections is mandatory tured side with the intact contralat- With the widespread use of CT

to definitively exclude incarcerated eral wall.10-12 scanning, the amount of the poste-

fragments and subtle joint incon- rior wall that is fractured or im-

gruity that can be missed on plain pacted (and therefore cannot support

radiographs (Fig. 3, A and B). Management Options the femoral head) can be accurately

During dislocation, the ligamen- determined before surgery. Several

tum teres frequently avulses a small Although Epstein2 recommended authors have attempted to define

bone fragment, which appears as a primary open reduction for all pos- how much of the posterior wall is

free fragment on the CT scan. As terior-fracture dislocations, most needed to maintain hip stability.10-12

long as it is small, low in the joint, protocols employ urgent closed There is general agreement that frac-

and restricted to the confines of the reduction with the use of adequate tures involving 50% or more of the

cotyloid fossa, such a fragment is sedation and muscle relaxation. posterior wall are unstable and de-

not in itself an indication for open Reduction is immediately followed mand surgical repair, whereas frac-

management. by clinical assessment of hip stabil- tures involving 20% or less are gen-

Computed tomography greatly ity performed by cautiously flex- erally stable and can be managed by

facilitates the assessment of frac- ing and slightly adducting the hip activity restriction with careful

ture comminution and residual dis- while feeling for subluxation. observation. Vailas et al10 demon-

placement. It is the ideal study for Sciatic nerve function should be re- strated no hip subluxation at 90

A B C

Fig. 3 Images of a 65-year-old man with a right posterior-wall fracture. A, After closed reduction, it is difficult to appreciate the extent of

the fracture on the AP radiograph. B, CT image shows an incarcerated osteochondral fragment in the joint (arrow), a comminuted rim

fragment, and a completely deficient posterior wall. C, Another, more distal CT scan shows marginal impaction.

Vol 7, No 1, January/February 1999 57

Posterior-Wall Acetabular Fractures

degrees of flexion, 20 degrees of patient who is managed nonopera- are used with reconstruction plates

internal rotation, and 20 degrees of tively with the use of only activity that allow contouring in all three

adduction in cadaver hemipelves restrictions. Radiographs (and planes. A spiked-ball pusher to

with fractures involving 25% of the repeat CT scanning if evidence of manipulate and reduce wall frag-

posterior wall if the posterior capsule instability exists) should be ob- ments and a T-handled universal

was intact. Of the 9 hips with a com- tained 1, 3, 6, and 12 weeks after chuck mounted with a Schanz

plete capsulectomy, only 1 (11%) fracture, at the minimum. screw, which can be inserted into

was unstable. the greater trochanter to distract

There is no consensus on treat- the femoral head, are helpful acces-

ment of fractures that are clinically Surgical Treatment sories (Fig. 4). As blood loss is

stable but involve 20% to 50% of the rarely less than 700 to 1,000 mL,

posterior wall. For these fractures, For isolated injuries, if the hip is intraoperative red blood cell salvage

treatment decisions should be reduced and nerve function is sta- systems are usually an effective

based on the patientÕs clinical situa- ble, emergency operation is not adjunct to minimize transfusion

tion (age, activity level, expecta- warranted. Surgery should pro- requirements.

tions, other injuries) as well as the ceed as soon as the patient, the Use of somatosensory evoked

likelihood that the surgeon can operating suite, and the surgical potentials to monitor sciatic nerve

achieve the desired surgical result team are prepared, usually within function intraoperatively remains

without complications. Although 72 hours of injury. Maintaining the controversial. The technique is rec-

the long-term effect on joint biome- hip in mild abduction and external ommended by some authors to

chanics of reducing the contact area rotation should obviate the need help minimize the risk of iatrogenic

of the posterior wall has not been for preoperative skeletal traction. nerve insult,5,18 but others consider

adequately studied, Olson et al 13 If there is gross instability or if it unnecessary and have reported

demonstrated near doubling of the there are bone fragments within very low rates of neurologic com-

contact force on the superior aspect the joint, skeletal traction to neu- plications without the added

of the acetabulum after simulated tralize the joint reaction force is expense and surgical time associat-

posterior-wall fracture in cadavers. indicated to prevent secondary ed with monitoring.19

Subsequently, they showed that mechanical damage to the articular An operating table that allows

even small rim fractures that would cartilage. unrestricted multiplanar and ob-

not cause clinical instability greatly Most of the instruments and lique fluoroscopic visualization of

altered joint-contact characteris- implants necessary to manage a the pelvis is preferred over a stan-

tics.14 posterior-wall fracture are available dard operating table or a fracture

If the hip is stable and closed in general orthopaedic operating table because it greatly facilitates

management is elected, bed rest is rooms. Small-fragment (3.5-mm) intraoperative assessment of the

instituted until the acute pain of the cortical screws of standard lengths reduction and fixation. The C arm

fracture-dislocation subsides. Most

authors believe that skeletal trac-

tion is not indicated. Historically, a

prolonged period of bed rest with

or without traction has been recom-

mended, but the need for this has

never been documented. 12,15 Re-

strictions against provocative Fig. 4 Instruments and

implants for treatment of

ranges of motion (Òtotal hip precau- posterior-wall fractures:

tionsÓ against adduction, internal from left to right, spiked-ball

rotation, and excessive flexion) pusher, T-handled universal

chuck with Schanz screw,

until capsular healing occurs cer- implant template, 3.5-mm

tainly appear appropriate, but bed reconstruction plates, recon-

rest longer than that necessary for struction plate bending

irons, and pliers.

comfort is not justified by any avail-

able data.16 Weight bearing should

be limited until there is evidence of

fracture healing.13,17 It is impera-

tive to monitor very closely any

58 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Michael R. Baumgaertner, MD

is positioned to be brought perpen- The skin and fascial incisions are nus tendon exits the inner pelvis

dicular to the table on the side centered at the posterosuperior through the lesser notch. This ten-

opposite the surgeon. With combi- aspect of the greater trochanter and don can be sutured to the gluteus

nations of table tilt and C-arm cant extend distally along the shaft and fascia to create a soft-tissue sling

and rotation, AP and Judet views proximally toward, but not entirely that retracts and protects the sciatic

can be obtained, as well as individ- to, the posterior superior iliac spine. nerve from the edge of a blunt-

ual oblique views that show screws The gluteus maximus muscle is tipped nerve retractor maintained

end-on or in perfect profile to con- split proximally until the first cross- in the lesser notch. Nerve retractors

firm exact length and position rela- ing branches of the inferior gluteal in the greater notch, where the

tive to the joint and pelvic cortices. nerve are reached (further dissec- nerve is unprotected, should be

The Kocher-Langenbeck poste- tion will denervate the part of the used cautiously or not at all.

rior approach is always used for muscle anterosuperior to the inci- If further inferior exposure is

isolated posterior-wall acetabular sion). The osseous insertion of the necessary, the origin of the quadra-

fractures. The patient can be in the gluteus maximus onto the femur is tus femoris as well as the ham-

lateral or prone position with the routinely released about 1 cm from strings can be taken down off the

involved extremity draped freely. its attachment to facilitate atrau- ischium. The pudendal nerve is

Although lateral positioning is matic posterior retraction. medial to the field and is not at risk.

more familiar to most surgeons, the Careful posteromedial dissection Hip extension and knee flexion are

prone position is preferred if there on the superficial surface of the maintained throughout the proce-

is an extensive posterior-wall frac- quadratus femoris will identify the dure, and the sciatic nerve is inter-

ture with gross instability or if the sciatic nerve, which is frequently in mittently inspected for inadvertent

fracture involves the roof of the two physically separate trunks at compromise.

acetabulum, because prone posi- this level. The lateral edge of the The gluteus minimus is elevated

tioning tends to slightly extend and nerve is then followed proximally off the capsule and ilium as neces-

abduct the hip, thus helping to through the fracture zone to where sary. It is important to cautiously

keep the femoral head reduced. In it exits the pelvis through the elevate near the superior border of

addition, the hip extension afford- greater sciatic notch, deep to the the sciatic notch to avoid laceration

ed by prone positioning (along piriformis muscle. With the nerve of the superior gluteal nerve, artery,

with knee flexion) decreases the identified and freed from imping- or vein, which may lie directly on

risk of stretch injury to the sciatic ing bone fragments, any blood- bone at this level. Anterior and

nerve. filled bursal tissue or avulsed mus- superior exposure is facilitated by

It is important to appreciate that culature can be safely debrided. hip abduction, which relaxes the

the approach for repair of a posterior- The interval between the inferior muscle and protects the superior

wall acetabular fracture is not the gemellus and the quadratus femoris gluteal nerve from traction palsy.

same as a posterior approach for is identified to avoid any inadver- The field can be maintained by

total hip arthroplasty. Anatomic tent dissection into the quadratus, placing Steinmann pins into the

planes are blurred due to muscular which would risk injury to the superolateral ilium.

hematoma from the recent trauma, medial femoral circumflex artery The first step in the reduction

and landmarks that are normally supplying the femoral head. The and fixation stage is always to

easily identified may be absent or tendons of the piriformis and obtu- inspect the joint. The wall frag-

markedly distorted. The sciatic rator internus are identified and ments are rotated back on their cap-

nerve is directly at risk as it passes carefully elevated off the joint cap- sular attachments, and the fracture

through the zone of injury and sule before sectioning. This allows surfaces are debrided of clot and

should be visually identified in the fractured wall fragments to callus. A Schanz screw placed into

every case, as it is immediately maintain their capsular attach- the trochanter is usually adequate

superficial to where implants must ments, which are frequently their to distract the femoral head, allow-

be placed. Perhaps the most im- only remaining blood supply. The ing examination of both articular

portant difference between fracture tendons are cut in midsubstance, surfaces, removal of incarcerated

surgery and replacement arthro- and the muscle ends are tagged. fragments, and flushing of debris

plasty is that the viability of the Retraction on these muscles allows from the joint. The size and shape

wall fragments and the femoral exposure of the retroacetabular sur- of any free cartilaginous fragments

head itself must be maintained; dis- face posteriorly to the border of the should be noted before they are dis-

section must proceed with this greater sciatic notch and the bursa carded. Free osteochondral frag-

caveat in mind. around which the obturator inter- ments of significant size are marked

Vol 7, No 1, January/February 1999 59

Posterior-Wall Acetabular Fractures

for orientation and set aside for tached to the capsule is attempted capsule and allows the fragments to

later reconstruction. If sustained only after the correction of any mar- be manipulated. A spiked-ball push-

distal retraction is desired, the ginal impaction, as this step prevents er is helpful in completing and main-

femoral distractor can be used effec- further unobstructed inspection of taining the reduction. Alternatively,

tively with one pin in the ilium and the articular surface. Slight abduc- temporary fixation can be achieved

the other in the trochanter. tion and external rotation relaxes the with small Kirschner wires directed

After joint cleansing, the femoral

head is reduced to the intact acetab-

ulum, and the quality of the joint

reduction is evaluated. An anatomic

reduction is implied if only the

edge of intact acetabular articular

surface is seen through the fracture

plane, and it is concentric and per-

fectly satisfied by the femoral head.

Marginal impaction exists if there is

any acetabular cartilage that does

not anatomically cup the reduced I

femoral head but instead is rotated

to face toward the plane of the frac-

ture. If not corrected, not only will

this aspect of the joint be incongru- W

G

ent, but the displaced articular

F

osteochondral segment will prevent

anatomic reduction of the overlying

wall fragment. Therefore, frag-

ments that are marginally impacted A B

must be recognized, elevated, and

supported with bone graft before

addressing other wall fragments.

The concentrically reduced fem-

oral head acts as a template to guide

the reduction. A narrow Cobb eleva-

tor can be used to create a plane

along the cortex of the quadrilateral

surface, deep to the depressed articu- F

lar surface and underlying cancellous

I

bone, and then to rotate the frag-

G

ments en bloc to elevate the depres- W

sion (Fig. 5). Any free osteochondral

fragments are reoriented and

reduced to the head as well. To sup-

port the reduced joint surface, a bone

graft from the greater trochanter is C D

packed into the defect that is created

Fig. 5 Technique for dealing with marginal impaction and a free osteochondral fragment.

behind the elevator. The femoral A, With the femoral head concentrically reduced to the intact acetabulum, the wall frag-

head prevents overelevation but ment with attached capsule (W) is reflected with a dental pick to reveal the marginal

allows aggressive impaction of the impaction (I) and the free osteochondral fragment (F), which is temporarily removed. B,

After harvesting of cancellous autograft (G) from the greater trochanter, an elevator is used

graft into the defect such that after to undermine and derotate the impacted fragment. The femoral head guides the reduction

the procedure, the grafted area and prevents overelevation. The autograft is impacted into the defect created by elevation.

appears more dense than the sur- C, After repositioning and support of the osteochondral free fragment with additional

graft, the wall fragment is finally repositioned. As the joint is no longer visible, the reduc-

rounding cancellous bone (Fig. 6). tion must be judged from the retroacetabular fracture line. D, The reconstructed posterior

Reduction and fixation of poste- wall is supported by a buttress plate and an appropriately directed lag screw.

rior-wall rim fragments that are at-

60 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Michael R. Baumgaertner, MD

buttress plate at least 6 to 9 mm

from the acetabular rim and direct-

ing the screws parallel or posterior

to the coronal plane helps to de-

crease the incidence of penetration.

The use of specially modified

spring plates has been suggested

for the control of rim fragments

deemed critical for stability but too

small for lag-screw fixation and too

peripheral to be adequately but-

tressed. 17,22 This technique in-

volves cutting and acutely bending

the end of a one-third tubular plate

Fig. 6 Postoperative CT images corresponding to Figure 3, B and C. Some devitalized to fashion two hooks that can catch

articular cartilage had to be discarded. Note densely impacted graft supporting the joint

surface but preventing complete reduction of the retroacetabular cortex. The safe corridor the rim fragment. The plate is con-

of the screw and the trochanteric bone-graft donor site can also be seen. toured so that its central section is

raised off the bone. When the plate

is anchored to the bone, with either

a screw or an overlying reconstruc-

away from the joint. The quality of Screws must be directed away tion plate, the spring plate bends

the joint reduction must frequently from the joint to avoid penetration, and fully engages the spikes in the

be inferred from the reduction of the but because of the small fragments rim fragment (Fig. 8). The surgeon

retroacetabular cortical fracture lines frequently involved, the depth of who elects to use this technique

and the continuity of the posterior the acetabulum, and the fact that the must be cognizant of the fact that

rim. joint cannot be easily visualized failure to position the hooks prop-

Definitive fixation of the wall after fracture reduction, violation of erly or postoperative displacement

fracture generally requires buttress the joint can occur. Suggestions for or even resorption of the rim frag-

plating. Very rarely, a large single avoiding this complication have ment may expose the femoral head

fragment can be adequately stabi- come from various authors, includ- to the plate itself.

lized with three to five lag screws. ing Bosse,20 who noted that screws Before wound closure, the hip is

Goulet et al 17 demonstrated that placed in any position on the acetab- taken through a range of motion to

the combination of a buttress plate ular rim would not violate the joint confirm the stability of fixation.

and lag screws provided a fourfold as long as they were placed in the

increase in local effective stiffness coronal plane perpendicular to the

(P<0.05) and doubling of the load long axis of the body. However, as

OK OK

to failure (3,306 vs 1,666 N [P=0.05]) these planes of reference can be dif-

in a posterior-wall fracture model ficult to assess intraoperatively,

Unsafe

compared with the use of two lag other methods of assessment should

screws alone. A 3.5-mm straight be employed as well.

reconstruction plate with seven to Placing Kirschner wires tangen-

nine holes was used. It can be tial to the articular surface under OK

helpful to contour the plate on a direct vision at the proximal and dis-

pelvic model preoperatively and tal extent of the intact acetabular rim

subsequently fine-tune the shape of allows a fixed plane of reference.1

the plate in the operating room. Screws placed parallel to or directed

Leaving the plate very slightly away from these wires should avoid

underbent aids in the reduction. If the joint (Fig. 7). Letournel 1 de-

the plate is fixed to the ischium scribed, and Ebraheim et al 21

with distally directed screws and to attempted to quantitate, the relation-

the lateral aspect of the ilium with ship between the distance from the

Fig. 7 Placement of a Kirschner wire tan-

superiorly directed screws, it will acetabular rim and the angle of the gential to the joint surface provides a refer-

be slightly tensioned as it is seated, screw needed to safely avoid the ence for safe screw location and direction.

compressing the wall fragments. joint. In general, maintaining the

Vol 7, No 1, January/February 1999 61

Posterior-Wall Acetabular Fractures

tion or the position of the hard-

ware, a postoperative CT scan can

be obtained. Fracture healing and

the status of the joint should be

monitored radiographically with

an AP view of the pelvis 6 weeks,

12 weeks, and 6, 12, and 24 months

after surgery (Fig. 10).

Motion restrictions against ad-

duction, internal rotation, and ex-

cessive flexion are maintained for 4

to 6 weeks. Even though the fixa-

tion rarely involves the area of the

joint that resists the resultant

forces of weight bearing, touch-

down weight bearing should be

maintained for a period of at least

6 to 8 weeks. Olson et al 13 have

shown that even perfect anatomic

A B

reduction and rigid internal fixa-

Fig. 8 Images of a 20-year-old man with a multifragment posterior-wall fracture. A, CT tion of a simple posterior-wall frac-

scan demonstrates marginal impaction, wall comminution, and a peripheral rim fragment ture does not restore normal load

attached to the posterior capsule. B, Follow-up radiograph obtained 1 year after surgery

shows the rim fragment captured by a spring plate. The plate lies under the buttress plate

transfers across the joint. In an-

and is fixed additionally by a screw. other study, Goulet et al17 noted a

small margin of safety between

construct strength and expected

physiologic loads.17

Additionally, the surgeon should bolism prophylaxis.23 Before dis- Strengthening exercises should

palpate and listen for any grating charge, a complete set of pelvic start at 6 weeks and continue for at

of the joint with motion, suggest- radiographs should be obtained in least 6 months. Dickinson et al24

ing misplaced hardware. It is very the radiology suite unless the intra- examined patients an average of 21

helpful to manipulate the position operative films are of excellent months after posterior-wall acetab-

of the table and the C arm so that quality. If any question remains ular surgery (minimum, 6 months)

screws near the joint are viewed regarding the quality of the reduc- and reported a 43% reduction in

end-on and appear as a circle on

the monitor. If the projection

shows the implant outside the joint

clear space, the screw is unques-

tionably safe (Fig. 9). Any muscle

of questionable viability should be

resected before the torn capsule

and the tendons of the short rota-

tors and gluteus maximus inser-

tion are repaired anatomically.

The fascia and dermis are then

closed in routine fashion. Hard-

copy film of the key fluoroscopic

images as well as an AP view of

the pelvis should be obtained be-

fore the patient leaves the operat-

ing room.

Fig. 9 Intraoperative oblique fluoroscopic images obtained before buttress-plate applica-

Postoperatively, patients com- tion suggest (left) and confirm (right) safe screw placement by showing the two lag screws

plete their perioperative antibiotic end-on and outside the joint clear space.

regimen and continue thromboem-

62 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Michael R. Baumgaertner, MD

A B

Fig. 10 A, Postoperative obturator oblique view of same patient shown in Figures 3 and 6 demonstrates the reconstructed posterior wall,

the plate contour, and the diverging screw pattern. B, Intermediate follow-up AP radiograph obtained at 30 months shows well-

preserved joint space.

abductor strength in patients who and the experience of the surgical approaches have been used, rates

had satisfactory reductions and team. 5 Letournel and Judet 1 re- as high as 42% within the first

who had completed a postopera- duced the rate of sciatic palsy from year after surgery have been

tive physical therapy program. 18% in their first 126 cases in which reported. 25 Rapid mechanical

They postulated that the weakness the Kocher-Langenbeck approach destruction of the femoral head

was permanent and was related to was used to 3.3% in the subsequent can occur from the injury itself,

the amount of exposure and the 211 cases. Almost invariably, the due to osteochondral impaction or

force of retraction on the superior peroneal division is injured with or cartilage crushing, or can be the

gluteal neurovascular bundle dur- without some tibial compromise, result of inadequate reduction,

ing surgery. and although the prognosis for loss of reduction with recurrent

improvement is good, it is uncom- instability, or violation of the joint

mon to regain completely normal by inadvertently retained bone

Complications muscle and sensory function. Al- fragments or screws. These diag-

though the primary means used to noses should be excluded before

Hematoma and infection are rare but avoid nerve injury are visualization considering a diagnosis of post-

serious complications that are best of the nerve and positioning of the traumatic osteonecrosis of the

managed prophylactically. Their extremity to minimize tension dur- femoral head, which does not pre-

occurrence necessitates prompt sur- ing retraction, somatosensory sent until at least several months

gical drainage. Like thromboem- evoked potential monitoring has after injury. Epstein 2 identified

bolism, they are not unique to been used to identify nerve com- osteonecrosis in 5.3% of surgically

acetabular fractures; therefore, their promise so that corrective actions treated posterior-wall fractures.

diagnosis and treatment will not be can be taken before irreversible Letournel and Judet 1 reported a

discussed further. changes occur.5,18 7.5% incidence of osteonecrosis in

Iatrogenic injury to the sciatic Osteonecrosis following opera- 227 fractures that included a pos-

nerve is related not only to fracture tive management of acetabular terior dislocation and that were

pattern and approach but also to fractures is generally overdiag- treated surgically within 21 days

the preoperative status of the nerve nosed. When Kocher-Langenbeck of injury.

Vol 7, No 1, January/February 1999 63

Posterior-Wall Acetabular Fractures

Heterotopic bone formation Outcome rate of arthrosis for posterior-wall

occurs less frequently after a fractures that were not reduced

Kocher-Langenbeck approach for Patients with posterior hip disloca- anatomically. Overall, Letournel

a posterior-wall acetabular frac- tions that are associated with mini- reported an 18% rate of unsatisfac-

ture than after an extensile ap- mal acetabular rim fractures do tory outcome for posterior-wall

proach for associated fractures. well provided reduction is prompt fractures.

Nevertheless, it still occurs in 20% and atraumatic.16 There is no ques- Femoral head impaction, carti-

of patients who have not received tion that unstable fracture-disloca- lage necrosis, and posterior-wall

prophylactic therapy and is clini- tions that receive delayed treatment resorption can lead to arthrosis

cally significant (Brooker grade III have dismal clinical outcomes, with even after anatomic reconstruction

or IV) in more than 7%.1 Male sex failure rates approaching 90%.1,2,16 of the acetabulum. Despite achiev-

and head injury are factors that It is in the light of these extremes ing perfect reductions in all 22

tend to increase the risk. Treat- that the results of acute stabilization posterior-wall fractures treated,

ment with indomethacin (25 mg should be viewed. In the study of Matta had a 32% clinical failure

three times a day, starting on the Pantazopoulos et al,31 more than rate in this group, higher than that

day of surgery and continuing for 90% of patients who had under- for any other fracture pattern in his

4 to 6 weeks) has been recom- gone anatomic reduction of a poste- series of 262 fractures.4

mended as effective, safe, and rior-wall fracture had a very good

inexpensive prophylaxis against clinical result 2 to 15 years (average,

heterotopic ossification26,27; how- 7 years) postoperatively, compared Summary

ever, a recent randomized pro- with only 50% of patients whose

spective study by Matta and reductions had 1 to 3 mm of resid- Patients who sustain an unstable

Siebenrock28 questions the efficacy ual displacement. posterior-wall acetabular fracture

of this method. Low-dose periop- In LetournelÕs series,1 19 (16%) have a guarded prognosis. An

erative irradiation (700 to 1,000 of 119 perfectly reduced posterior- anatomic reduction is achievable in

cGy within 48 hours of surgery) is wall fractures were found to have the great majority of cases and is a

effective in reducing the incidence developed significant osteoarthro- prerequisite to long-term hip sur-

and severity of heterotopic ossifi- sis at follow-up, which was as long vival. Although not even a perfect

cation after acetabular fracture,29,30 as 25 years. The rate of posttrau- surgical reconstruction of a joint will

but the unknown potential for late matic arthrosis after a perfectly guarantee long-term function, that

complications from radiation dis- reduced posterior-wall fracture goal must be the mind-set of sur-

courage treatment with this mo- was higher than the 10% rate for geons who choose to treat this injury,

dality for the isolated posterior- all types of acetabular fractures because the results of imperfect or

wall fracture in the typically that had an anatomic reduction, unstable reductions are clearly infe-

young patient. but was much lower than the 38% rior and usually unsatisfactory.

References

1. Letournel E, Judet R; Elson RA (trans- sensory evoked potential monitoring cation of Fractures of Long Bones. New

ed): Fractures of the Acetabulum, 2nd in the surgical treatment of acute, dis- York: Springer-Verlag, 1996.

ed. Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1992. placed acetabular fractures: Results of 9. Brumback RJ, Holt ES, McBride MS,

2. Epstein HC: Posterior fracture-disloca- a prospective study. Clin Orthop 1994; Poka A, Bathon GH, Burgess AR:

tions of the hip: Long-term follow-up. 301:213-220. Acetabular depression fracture accom-

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974;56:1103-1127. 6. Judet R, Judet J, Letournel E: Fractures panying posterior fracture dislocation

3. Saterbak AM, Marsh JL, Brandser E, of the acetabulum: Classification and of the hip. J Orthop Trauma 1990;4:42-48.

Nepola JV, Turbett T: Outcome of sur- surgical approaches for open reduc- 10. Vailas JC, Hurwitz S, Wiesel SW:

gically treated posterior wall acetabu- tionÑPreliminary report. J Bone Joint Posterior acetabular fracture-disloca-

lar fractures. Orthop Trans 1997;21:627. Surg Am 1964;46:1615-1646. tions: Fragment size, joint capsule, and

4. Matta JM: Fractures of the acetabu- 7. Orthopaedic Trauma Association stability. J Trauma 1989;29:1494-1496.

lum: Accuracy of reduction and clini- Committee for Coding and Classifi- 11. Keith JE Jr, Brashear HR Jr, Guilford

cal results in patients managed opera- cation: Fracture and dislocation com- WB: Stability of posterior fracture-dis-

tively within three weeks after the pendium. J Orthop Trauma 1996;10 locations of the hip: Quantitative as-

injury. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996;78: (suppl 1):73. sessment using computed tomography.

1632-1645. 8. MŸller ME, Nazarian S, Koch P, J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988;70:711-714.

5. Helfet DL, Schmeling GJ: Somato- Schatzker J: The Comprehensive Classifi- 12. Calkins MS, Zych G, Latta L, Borja FJ,

64 Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons

Michael R. Baumgaertner, MD

Mnaymneh W: Computed tomogra- 19. Middlebrooks ES, Sims SH, Kellam JF, 26. McLaren AC: Prophylaxis with indo-

phy evaluation of stability in posterior Bosse MJ: Incidence of sciatic nerve methacin for heterotopic bone: After

fracture dislocation of the hip. Clin injury in operatively treated acetabu- open reduction of fractures of the

Orthop 1988;227:152-163. lar fractures without somatosensory acetabulum. J Bone Joint Surg Am

13. Olson SA, Bay BK, Chapman MW, evoked potential monitoring. J Orthop 1990;72:245-247.

Sharkey NA: Biomechanical conse- Trauma 1997;11:327-329. 27. Moed BR, Maxey JW: The effect of

quences of fracture and repair of the 20. Bosse MJ: Posterior acetabular wall indomethacin on heterotopic ossifica-

posterior wall of the acetabulum. J fractures: A technique for screw place- tion following acetabular fracture

Bone Joint Surg Am 1995;77:1184-1192. ment. J Orthop Trauma 1991;5:167-172. surgery. J Orthop Trauma 1993;7:33-38.

14. Olson SA, Bay BK, Pollak AN, Sharkey 21. Ebraheim NA, Waldrop J, Yeasting 28. Matta JM, Siebenrock KA: Does

NA, Lee T: The effect of variable size RA, Jackson WT: Danger zone of the indomethacin reduce heterotopic bone

posterior wall acetabular fractures on acetabulum. J Orthop Trauma 1992;6: formation after operations for acetabu-

contact characteristics of the hip joint. 146-151. lar fractures? A prospective random-

J Orthop Trauma 1996;10:395-402. 22. Mast J, Jakob R, Ganz R: Planning and ized study. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1997;

15. Rowe CR, Lowell JD: Prognosis of Reduction Technique in Fracture Surgery. 79:959-963.

fractures of the acetabulum. J Bone Berlin: Springer-Verlag, 1989, p 254. 29. Moed BR, Letournel E: Low-dose irra-

Joint Surg Am 1961;43:30-59. 23. Fishmann AJ, Greeno RA, Brooks LR, diation and indomethacin prevent het-

16. Aho AJ, Isberg UK, Katevuo VK: Ace- Matta JM: Prevention of deep vein erotopic ossification after acetabular

tabular posterior wall fracture: 38 thrombosis and pulmonary embolism fracture surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br

cases followed for 5 years. Acta Orthop in acetabular and pelvic fracture 1994;76:895-900.

Scand 1986;57:101-105. surgery. Clin Orthop 1994;305:133-137. 30. Bosse MJ, Poka A, Reinert CM, Ell-

17. Goulet JA, Rouleau JP, Mason DJ, Gold- 24. Dickinson WH, Duwelius PJ, Colville wanger F, Slawson R, McDevitt ER:

stein SA: Comminuted fractures of the MR: Muscle strength testing following Heterotopic ossification as a complica-

posterior wall of the acetabulum: A biome- surgery for acetabular fractures. J tion of acetabular fracture: Prophylaxis

chanical evaluation of fixation methods. Orthop Trauma 1993;7:39-46. with low-dose irradiation. J Bone Joint

J Bone Joint Surg Am 1994;76:1457-1463. 25. Daum WJ, Scarborough MT, Gordon Surg Am 1988;70:1231-1237.

18. Baumgaertner MR, Wegner D, Booke JW Jr, Uchida T: Heterotopic ossifica- 31. Pantazopoulos T, Nicolopoulos CS,

J: SSEP monitoring during pelvic and tion and other perioperative complica- Babis GC, Theodoropoulos T: Surgical

acetabular fracture surgery. J Orthop tions of acetabular fractures. J Orthop treatment of acetabular posterior-wall

Trauma 1994;8:127-133. Trauma 1992;6:427-432. fractures. Injury 1993;24:319-323.

Vol 7, No 1, January/February 1999 65

You might also like

- Fractures of The Posterior Wall of The Acetabulum: Michael R. Baumgaertner, MDDocument12 pagesFractures of The Posterior Wall of The Acetabulum: Michael R. Baumgaertner, MDFaiz NazriNo ratings yet

- Yar Boro 2016Document13 pagesYar Boro 2016saimanojkosuriNo ratings yet

- Comminuted Patella FracturesDocument8 pagesComminuted Patella FracturesKirana lupitaNo ratings yet

- Humerus FractureDocument5 pagesHumerus FracturecyahiminNo ratings yet

- Displaced Acetabular FracturesDocument11 pagesDisplaced Acetabular FracturesJayNo ratings yet

- 2008 - Elbow Dislocation - OCNADocument7 pages2008 - Elbow Dislocation - OCNAharpreet singhNo ratings yet

- Olecranon Fractures A Critical Analysis Review.9Document10 pagesOlecranon Fractures A Critical Analysis Review.9jcmarecauxlNo ratings yet

- Humeral Non UnionDocument12 pagesHumeral Non Unionmmqk122No ratings yet

- KSRR 27 1Document9 pagesKSRR 27 1darshan tatiaNo ratings yet

- Acutrak Fixation of Comminuted Distal Radial FracturesDocument4 pagesAcutrak Fixation of Comminuted Distal Radial Fracturessanjay chhawraNo ratings yet

- Distal Humerus Fractures: Roongsak Limthongthang, MD, and Jesse B. Jupiter, MDDocument10 pagesDistal Humerus Fractures: Roongsak Limthongthang, MD, and Jesse B. Jupiter, MDRadu UrcanNo ratings yet

- Manejo de Fracturas Mediales de Cadera 2015 Femoral Neck Fractures - Current ManagementDocument9 pagesManejo de Fracturas Mediales de Cadera 2015 Femoral Neck Fractures - Current ManagementSergio Tomas Cortés MoralesNo ratings yet

- Comminuted Intraarticular Fractures of The Tibial Plateau Lead To Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis of The Knee: Current Treatment ReviewDocument7 pagesComminuted Intraarticular Fractures of The Tibial Plateau Lead To Posttraumatic Osteoarthritis of The Knee: Current Treatment ReviewGustavoBecerraNo ratings yet

- The Knee - Breaking The MR ReflexDocument20 pagesThe Knee - Breaking The MR ReflexManiDeep ReddyNo ratings yet

- Classification of Pelvic Fractures and Its Clinical RelevanceDocument6 pagesClassification of Pelvic Fractures and Its Clinical RelevanceMohamed AzeemNo ratings yet

- Managementofdistal Femurfracturesinadults: An Overview of OptionsDocument12 pagesManagementofdistal Femurfracturesinadults: An Overview of OptionsDoctor's BettaNo ratings yet

- Distal Humerus Fractures: J. Whitcomb Pollock, MD, FRCSC, Kenneth J. Faber, MD, MHPE, FRCSC, George S. Athwal, MD, FRCSCDocument14 pagesDistal Humerus Fractures: J. Whitcomb Pollock, MD, FRCSC, Kenneth J. Faber, MD, MHPE, FRCSC, George S. Athwal, MD, FRCSCRadu UrcanNo ratings yet

- Acetabulum AOSR ENGDocument48 pagesAcetabulum AOSR ENGAdil SultaniNo ratings yet

- Tibial Plateau Fractures: A Review: P Fenton and K PorterDocument7 pagesTibial Plateau Fractures: A Review: P Fenton and K PorterDot DitNo ratings yet

- Orbital TraumaDocument20 pagesOrbital TraumaJezreel Ortiz AscenciónNo ratings yet

- Anterograde Percutaneous Treatment of Lesser Metatarsal Fractures Technical Description and Clinical ResultsDocument5 pagesAnterograde Percutaneous Treatment of Lesser Metatarsal Fractures Technical Description and Clinical ResultsRoyman MejiaNo ratings yet

- Advancesinthe Reconstructionoforbital Fractures: Scott E. Bevans,, Kris S. MoeDocument23 pagesAdvancesinthe Reconstructionoforbital Fractures: Scott E. Bevans,, Kris S. Moestoia_sebiNo ratings yet

- Percutaneous Osteosynthesis of The Distal Fractures of The Femur. Eladio Saura Mendoza e Eladio Saura SanchezDocument12 pagesPercutaneous Osteosynthesis of The Distal Fractures of The Femur. Eladio Saura Mendoza e Eladio Saura SanchezNuno Craveiro LopesNo ratings yet

- Elbow Fractures: Distal Humerus: The American Society For Surgery of The Hand.)Document15 pagesElbow Fractures: Distal Humerus: The American Society For Surgery of The Hand.)Radu UrcanNo ratings yet

- Treatment Options of Pelvic and Acetabular Fractures in Patients With Osteoporotic BoneDocument12 pagesTreatment Options of Pelvic and Acetabular Fractures in Patients With Osteoporotic Bonefajri_amienNo ratings yet

- Exposure Coronoid FXDocument9 pagesExposure Coronoid FXGiulio PriftiNo ratings yet

- Basic Paediatrics - Unit 1 - SupracondylarDocument8 pagesBasic Paediatrics - Unit 1 - SupracondylarMohamad RamadanNo ratings yet

- BackgroundDocument5 pagesBackgroundMaricar K. BrionesNo ratings yet

- Fracture Distal Humerus (Surgical Anatomy, Classification and Treatment)Document98 pagesFracture Distal Humerus (Surgical Anatomy, Classification and Treatment)drakkashmiri100% (4)

- Ankle Fracture-Dislocations: A ReviewDocument8 pagesAnkle Fracture-Dislocations: A ReviewAryo WibisonoNo ratings yet

- 6 - Injuries To The Ulnar Collateral Ligament o - 2018 - Clinical Orthopaedic Re PDFDocument4 pages6 - Injuries To The Ulnar Collateral Ligament o - 2018 - Clinical Orthopaedic Re PDFTolo CantallopsNo ratings yet

- Proximal Humeral Fracture Repair and RehabilitationDocument8 pagesProximal Humeral Fracture Repair and RehabilitationAnonymous UClts4nYNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Hip Dislocation: A ReviewDocument6 pagesTraumatic Hip Dislocation: A ReviewAna HurtadoNo ratings yet

- Thesis Umesh A2z.doc Final Thesis CorrectionDocument79 pagesThesis Umesh A2z.doc Final Thesis CorrectionRakesh JhaNo ratings yet

- Protrusio Acetabuli Diagnosis and TreatmentDocument10 pagesProtrusio Acetabuli Diagnosis and TreatmentFerney Leon BalceroNo ratings yet

- Cole 2013Document5 pagesCole 2013Angie MorrisNo ratings yet

- D5DADocument3 pagesD5DAdemoaccount demoNo ratings yet

- Late Fracture of The Hip After Reamed Intramedullary Nailing of The FemurDocument5 pagesLate Fracture of The Hip After Reamed Intramedullary Nailing of The FemurGordana PuzovicNo ratings yet

- 10.1007@s00264 019 04344 8Document12 pages10.1007@s00264 019 04344 8DavidNo ratings yet

- Fractures of The Cervical Spine: ReviewDocument7 pagesFractures of The Cervical Spine: ReviewMeri Fitria HandayaniNo ratings yet

- Posterior Shoulder Fracture-Dislocation A SystematDocument7 pagesPosterior Shoulder Fracture-Dislocation A SystematMarcos Burón100% (1)

- Distal Femur Fractures. Surgical Techniques and A Review of The LiteratureDocument8 pagesDistal Femur Fractures. Surgical Techniques and A Review of The Literaturerifqi13No ratings yet

- Bony SkierDocument6 pagesBony SkierChrysi TsiouriNo ratings yet

- Distal Radius Fractures 2009Document10 pagesDistal Radius Fractures 2009Un SerNo ratings yet

- Orbital Roof Fractures A Clinically Based Classification and Treatment AlgorithmDocument7 pagesOrbital Roof Fractures A Clinically Based Classification and Treatment AlgorithmEl KaranNo ratings yet

- FX Pelvic Rim Injury17Document8 pagesFX Pelvic Rim Injury17Antonio PáezNo ratings yet

- Stav SoucasnyDocument14 pagesStav SoucasnyTommysNo ratings yet

- Hip Dislocation: Current Treatment Regimens: Paul Tornetta III, MD, and Hamid R. Mostafavi, MDDocument10 pagesHip Dislocation: Current Treatment Regimens: Paul Tornetta III, MD, and Hamid R. Mostafavi, MDJaime Anaya Sierra100% (1)

- Scapulothoracic Dissociation: Trauma UpdateDocument5 pagesScapulothoracic Dissociation: Trauma UpdateFadlu ManafNo ratings yet

- The Unstable ElbowDocument17 pagesThe Unstable ElbowwerwrNo ratings yet

- Fractures of The Radial Head (2013)Document9 pagesFractures of The Radial Head (2013)Say MamenNo ratings yet

- Fractura e FalangsDocument16 pagesFractura e FalangsJulio Cesar Guillen MoralesNo ratings yet

- 278a PDFDocument10 pages278a PDFKhairul HukmiNo ratings yet

- Fractures of Clavicle AserDocument44 pagesFractures of Clavicle AserHeba ElgoharyNo ratings yet

- Fai 2007 0529Document7 pagesFai 2007 0529milenabogojevskaNo ratings yet

- Ankle FracturesDocument133 pagesAnkle FracturesAtiekPalludaNo ratings yet

- Surgical Stabilization of SpineDocument4 pagesSurgical Stabilization of SpineMaria Jonnalin SantosNo ratings yet

- LP Radius Ulna FractureDocument22 pagesLP Radius Ulna FractureMuhammad PanduNo ratings yet

- Initial Management of Acute Spinal Cord Injury: Stephen Bonner MRCP FRCA FFICM Caroline Smith FRCADocument8 pagesInitial Management of Acute Spinal Cord Injury: Stephen Bonner MRCP FRCA FFICM Caroline Smith FRCAMinaz PatelNo ratings yet

- Clinical Outcomes and Treatment of Hip Fractures.: Format Send ToDocument1 pageClinical Outcomes and Treatment of Hip Fractures.: Format Send ToJayNo ratings yet

- Arthroscopic Partial Trapeziectomy and Tendon Interposition For Thumb Carpometacarpal ArthritisDocument7 pagesArthroscopic Partial Trapeziectomy and Tendon Interposition For Thumb Carpometacarpal ArthritisJayNo ratings yet

- Bartons LiogamentotaxisDocument3 pagesBartons LiogamentotaxisJayNo ratings yet

- Revision THRDocument11 pagesRevision THRJayNo ratings yet

- Thromboembilism After ArthorplastyDocument5 pagesThromboembilism After ArthorplastyJayNo ratings yet

- Acetabular ReconstructionDocument2 pagesAcetabular ReconstructionJayNo ratings yet

- Acetabular FracturesDocument8 pagesAcetabular FracturesJayNo ratings yet

- 245 682 1 PBDocument8 pages245 682 1 PByunitaNo ratings yet

- NBR Leaflet Krynac 4955vp Ultrahigh 150dpiwebDocument2 pagesNBR Leaflet Krynac 4955vp Ultrahigh 150dpiwebSikanderNo ratings yet

- Child Health Services-1Document44 pagesChild Health Services-1francisNo ratings yet

- Glycerol MsdsDocument6 pagesGlycerol MsdsJX Lim0% (1)

- Culture Negative IsDocument29 pagesCulture Negative IsvinobapsNo ratings yet

- Transferring A Dependent Patient From Bed To ChairDocument5 pagesTransferring A Dependent Patient From Bed To Chairapi-26570979No ratings yet

- Glossary Mental Terms-FarsiDocument77 pagesGlossary Mental Terms-FarsiRahatullah AlamyarNo ratings yet

- Quality Manual: Pt. Ani Mitra Jaya Frozen ChepalopodDocument1 pageQuality Manual: Pt. Ani Mitra Jaya Frozen ChepalopodMia AgustinNo ratings yet

- EOHSP 09 Operational Control ProcedureDocument3 pagesEOHSP 09 Operational Control ProcedureAli ImamNo ratings yet

- Material Safety Data Sheet: 1 Identification of SubstanceDocument5 pagesMaterial Safety Data Sheet: 1 Identification of SubstanceRey AgustinNo ratings yet

- Behaviorism in Daily LifeDocument8 pagesBehaviorism in Daily LifeMichelleTongNo ratings yet

- Book StickerDocument4 pagesBook Stickerilanabiela90No ratings yet

- EDC Annual ReportDocument433 pagesEDC Annual ReportAngela CanaresNo ratings yet

- DoctrineDocument1 pageDoctrinevinay44No ratings yet

- Bellavista 1000 Technical - SpecificationsDocument4 pagesBellavista 1000 Technical - SpecificationsTri DemarwanNo ratings yet

- De La Cruz, Et Al. (2015) Treatment of Children With ADHD and IrritabilityDocument12 pagesDe La Cruz, Et Al. (2015) Treatment of Children With ADHD and Irritabilityjuan100% (1)

- Nutrition Case Study Presentation Slides - Jacob NewmanDocument27 pagesNutrition Case Study Presentation Slides - Jacob Newmanapi-283248618No ratings yet

- Lesson 8 - Extent of Factors Affecting Health in KirkleesDocument8 pagesLesson 8 - Extent of Factors Affecting Health in KirkleeswapupbongosNo ratings yet

- Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (Trali) : Description and IncidenceDocument9 pagesTransfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (Trali) : Description and IncidenceNanda SilvaNo ratings yet

- Part-IDocument507 pagesPart-INaan SivananthamNo ratings yet

- Formularium 2018 ADocument213 pagesFormularium 2018 Asupril anshariNo ratings yet

- Incident ReportDocument3 pagesIncident Reportجميل باكويرين موسنيNo ratings yet

- P1 Cri 089Document2 pagesP1 Cri 089Joshua De Vera RoyupaNo ratings yet

- Maslow TheoryDocument10 pagesMaslow Theoryraza20100% (1)

- Varma Practictioner GuideDocument9 pagesVarma Practictioner GuideGoutham PillaiNo ratings yet

- Usmart 3200T Plus BrochureDocument4 pagesUsmart 3200T Plus BrochureMNo ratings yet

- LNG Hazards and SafetyDocument60 pagesLNG Hazards and SafetyFernando GrandaNo ratings yet

- Affidavit - Rural Cess - ManjulaDocument9 pagesAffidavit - Rural Cess - Manjulagebrsf setgwgvNo ratings yet

- DLL Mod.1 Part 1 3rd QRTR g10Document4 pagesDLL Mod.1 Part 1 3rd QRTR g10rhea ampin100% (1)

- Phytophthora InfestansDocument10 pagesPhytophthora Infestansvas2000No ratings yet