Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Extrinsic Aids To Interpretation

Extrinsic Aids To Interpretation

Uploaded by

Khalil Ahmad0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views8 pagesOriginal Title

Extrinsic aids to interpretation

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

28 views8 pagesExtrinsic Aids To Interpretation

Extrinsic Aids To Interpretation

Uploaded by

Khalil AhmadCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 8

1

The extra statutory materials that can be used for the purpose of interpretation are called

extrinsic or extemal aids to interpretation. They are so used for the limited purpose of

ascertaining the context in which the words have been used in the statute. Such materials

‘can be conveniently grouped under the following heads:-

vA. Travaux preparatories or preparatory material

2+ Historical facts

‘J. Other statutes C Kefnence & Legislation)

4, Contempornea expositio

\-5: Dictionaries

1. Preparatory material: The process of legislative enactment of a statute produces a

range of material that can throw a light on the purpose & rationale of the enactment.

As a matter of principle such material-cannot be used to gi ins Jan

of all statutes. Lord Halsbury in Kilder v/s Dexter (1902) has observed that “the

‘worst person to construe a statute is the person who is responsible of its drafting. He

is very much disposed to confuse what he intended to do with the effect of the

language which, in fact, has been employed.” Nevertheless such material is relevant

in determining the circumstances in which the statute was enacted & the language

which has been used in its enactment.

Lauterpacht has given three reasons for the attitudes of the courts in England.

Firstly, that the declarations of a single house of the Parliament do not constitute law,

secondly, the deliberations of the houses were not published till the 18" century &

finally the courts asserted an independence from parliamentary control in the

performance of their functions.

The value of materials depends upon its kind & can be profitably discussed with

reference to that. Range of available material can be divided under the following

heads:

1) Statement of the object & reasons: The statement of objects & reasons is

/ appended to each bill at the time of its introduction in the house of the legislature.

The statement of the objects & reasons is not admissible for the purpose of

determining the intention of the legislature. i anguage used in the

statutes. However, it can be used for the limited purpose of (i) ascertaining the

conditions prevailing at the time of introduction 1 of the bills & (ii) determining the

purposes for Which the Bill was proposed. _ Lt ih.

The reason for which the statement of objects & reasons is not admissible as an

aid to ascertainment of the intention of the legislature is that the statement merely

reflects the intention of the mover of the bill & during its passage through legislature

that intent may be modified, lost or abandoned.

In Ashwin Kumar Ghosh v/s Arbind Bose (1952) Reliance was placed on the

statement of objects & reasons of the Bill, which was later, enacted as the S.C.

Advocates (Practice in H.C.) Act 1951 to show the meaning of the expression

tice in Secti ;

Practice in Section 7 Of the Act, Shastri C.J, held that the statement of the objects &

ons should led out as an aid to the intention of the language.

oe Seals state of Madras & Kerala y Justice Subba Rao

eae eee stil : objects & reasons for the (4 Amendment) bill

pesnanran An cea determining the circumstances

et & purpose of the

th Du inte

ed id that the purpose of Art 31A are intende

to protect agrarian

In T. Manickram & Co vain ag SC, the statement was used

determine the nature of the amefding legislation Tt was held that he seme

clarificatory. =

i Tn Jagdish Chandra Sinha v/s Eileen K. Patricia D’ Rozarie, it was held by the

\C that the statement of the object & res

: n accompanying a legislative Bill cannot

ete Meta the true meaning effect of he substantive povsion the substantive provision of the

legislation but it can certainly be pressed in to service for the limited

b purpose of

understanding the background, antecedent state of affairs & object of the legislation it

sought to achieve. eeereer eee ere eeeeeeeeereeee eee HH

evadoss v/s Veera Makali Ammau Koli Athalur AIR 1998 SC, the SC

tuled that statement of objects & reasons can be used for understanding the

background, the antecedent state of affairs & the evil sought to be remedied by the

statute,

In P.V. Narsimha Rao v/s State (CBI/SPE) AIR 1998 SC, Agarwal J said in his

judgement in the SC that the statement of the minister who had moved the Bill in the

Parliament can be looked at to ascertain the mischief sought to be remedied by the

legislation & the object & the purpose for which the legislation is enacted. The

statement of the minister however, is not taken into account for the purpose of

interpreting the provision Of Ihe POF ont £ obfecli can nats Lonwver, peshice

Ke Bhese sneaning 24 de poocds Used hy legichydise. qi

2) Speech at introduction of Bill: The speech made by the mover of the Bill at the

time of introduction in the House cannot be looked as a guide to the intention of the

legislature in enacting the statute. However, like the statement of reasons & object,

the speech is admissible only as a circumstantial evidence leading to the enactment of

_the statute. ‘The rule is same in England as well is ‘India. aH

In Re Mew (1862), the Presiding Judge referred to his own speech at the time of

introduction of the Bankruptcy Bill, but he was careful to observe that he did not do

so in determining the meaning of the language used in the statue. Court refused to

rely on the speech of the Presiding Judge, who moved the Bill to construe the

enactment.

In State of West Bengal v/s UOI, the Supreme Court held that statement made

by a Minister about the object & intention of the words used in the statute is capable

of acquisition of State owned lands. HH

InK P Varghese v/s IT Officer AIR 1981 SC, the SC observed that it is true that

the speeches made by the members of the legislatures on the floors of the house when

a Bill for enacting a statutory provision is being debated are inadmissible for the

purpose of interpreting the statutory provision. But the speech made by the mover of

the Bill can certainly be referred to for the purpose of ascertaining the mischief

sought to be amended by the legislature & the object & the purpose for which the

legislature is enacted. Theref

movi : ore, the speech made

moving the amendment i by the Finance Minister whil

relevant. ntodiucing Section $2(2) ofthe 1 Act, 1961 is extremely

3) Debates in the Legislature: In Engl

ee ‘ngland the rute is well extabli

a — a ‘ be eee atthe intention of the Legislature ee

Wer Rade ee 2¢ of ce aagets tn which the statute wan made In Rex vis

Cor were held to tracunsidered ircev mt ane inerrant ar a

earn tinier te ne ir ion of

Pr United ; cL a earlier practice retembléd England In U.S, vi Teate

Freigh ©. (1664), the U.S.A. Supreme Court held that the debates e Nd

Not control the meaning of statutes, The reasons for this attitude were: —

eee This trapossible to determine with certainty what construction was

Put upon an Act by the members of the legislative body that passed

it by resorting to speeches of the individual members thereof,

Those who did not speak May not have agreed with those who did

& those who spoke might differ from each other.

; However, congressional debates are admissible as evidence of circumstances jn

which a statute was made & of the evil, which if sought to remedy. Use may also be

thade of the debate to show ariy change in language, which was or was not made.

In India, in older days the Bombay & Calcutta High Courts did not permit a

refefence to thé debate in construirig a statute. The Allahabad HC in Kadir Baksh v/s

ad tak iew. Later On in Advocate General of —

Bhawani Prasad had taken the opposite view

the PC held that the debates could not be used for

Bengal v/s Premlal i tes

the meaning of a sfatute. The Judicial Committee in this case was

i Our SC has adoy i

considered to ascertain the intention of the legislature.

However, Kania CJ in Gopalan v/s State of Madras, Bhagwati J in Express

Newspaper Ws UOI (1958) & Subba Rao CJ in Golaknath case (1967) used the

debates to show whether a certain proposition was considered by the legislature,

4) Reports of Commissions: In England the practice is not to take into consideration

the Reports of Royal Commissions leading to particular enactment in order to

ascertain the intention of the legislature. Thus, in Katikaro of Uganda vis Attorney

General (1960), the Court refused to look into a white paper containing the

recommendation of Uganda constitutional conference to ascertain the intention

underlying the order in council incorporating the Uganda agreement. ea

On the contrary such commission Reports can be looked into to acces a

historical circumstances, which led to the enactment ofa particular statute. - a

Halsbury considered the Reports as the most accurate source of information

il, which the statute was intended to suppress.

ae SC in Mubarak Ali V/s State of Bombay (1957) held that the a “| -

Indian Law Commission on the drafting of IPC could be taken into consideral

as a matter of hi ae

the TPC, 1860,” & P9888 legitimate guide to the meani

In RS. Nayak v/s AR. Antul ee

of the committee which Preceded A AIR 1984 SC, it was held by the SC that

tiament 7 enactment of a legi eee

parflamentary committee & report of a commission ace oP report of joint

ee en pmo i ta

5) Reports of Legislative Committee: In f i

Committee was considered on the me hen Cebus: RgPert of Legislative

appropriately summarized the prevailing attitude in Eevee oT’ Deming has

Commissions observing: *eolgne Properties v/s LR.

We do not look at the exp ;

preface the Bill before the Puamen ee ih

Pages of Hansurd. All that the Court can do is ‘otake =

Judicial notice of the previous state of law & of other

matters generally known to well informed people.

On the contrary, in U.S.A. the reports of the committee are considered

more reliable & satisfactory source of assistance. In Imhoff-Bank Dyeing co vis

USS, it was held by the Federal Court that Committee Report could be rightly

Tegarded as possessing very considerable value of the explanatory nature

Tegarding the legislative intent.

In India, the English practice is followed. In Gopalan’s case, Kania CJ

referred to the proceedings of the drafting committee of the Constituent Assembly

to ascertain the circumstances in which objectives ‘presonal’ was introduced in

Art. 21 of the Constitution to qualify the word ‘liberty’.

Thus, it is well settled that the report of the committee cannot control the

meaning of the enactment but may be taken to examine the surrounding

circumstances in construing the Constitution. In Lok Shikshan Trust v/s LT.

Commissioner (1977), Beg J held that the report could be used to find out the

reasons for an enactment.

2. Historical facts: \t is permissible to refer to historical facts & circumstances

ing the t in construing it. However, such reference cannot override

¢ plain & unequivocal language of an enactment. It is only when the language is

the .

ambi recourse can be had to the historical facts to ascertain the state of law &

the object of the statute. Lord Jessel in Holmes v/s Guy (1877) said that such an

investigation enabled the Court to funle the inienton ofthe legislature

In interpreting the old statutes the historical dimension can be of great

importance. In Ridge v/s Baldwin (1964) the House of Lords added the requirement

of hearing to the provisions of a statute, which empowered the Metropolitan aan

to dismiss a police constable even though statutes never mention it. This was possi le

on the ground that older statutes always presumed that such requirement woul

read upreme i is relevant in

ia, Si Court bas also held that the prior state of law is relevant

seining dein er racarg of Taw, the process by which the law was evolved, & he

determining the meses =

(ena.

/ evil sought to be Temoved, in

/ “he Supreme Uae an State of West Bengal v/s MLN, Ba

j subordinate judic

/ Constitution. Sin

Ponto!” includ isciplinary process,

‘Owever, at this time of Passing of enact ir

not meaner B lactment reference to the circumstances does

sor ea iat Te anguage used should be h icable in later scientific, social,

hi (1966),

history of constitutional provisi sat

nY '0 ascertain the meaning of control in An 235 ofthe

ce in its opinion the expression was ambiguous t

In Attorney General v/s Edisson Tele; hone Co (1 word Telephone

Considered to be included in the connotation of the word "Telepan Teceh i

telephone wn at the time of enactment of the statute,

___ There is a need | sive interpretation of enactment to meet changing

situation applies with Greater force to constitutional interpretation. The Supreme

Court of India has acknowledged the need for the-need-for a liberal constructi

— eral construction of

pe Constitution. In State of West Ben v/s Anwar Ali Sarkar (1950) Vivian Bose

“The Constitution must in my judgement be left elastic enough to meet

from time to time the altering conditions of a changing world with its

shifting emphasis & differing needs.”

In S.P. Gupta v/s President of India AIR 1982 SC, observed that legislative

history of a constitutional provision though not directly germane for the purpose of

construing a statute may, however, be used in exceptional cases to denote the

beginning of legislative process which results in the logical end & the finale of the

statutory provision, but in no case the legislative history be a substitute for an

interpretation which is in direct contravention of the Statutory provision concerned.

Sf Other statutes: \n interpreting a statute both earlier & later statutes are relevant to a

limited extent. The rationale behind the use of other statute is that the legislature is

presumed to be conversant withthe stale ofexising ow.

The extent of the aid that can be derived from the other statutes in interpreting

the statutes depends on the nature of such other statutes. Three distinct groups have

been identified by the Craines: :

1) Statutes in pari materia with the statutes under construction. ate

2) Earlier statutes not strictly in pari materia with the statutes under construction but

in some way relating to or same subject matters.

3) Seen statutes amounting to parliamentary exposition of the statutes under

construction.

‘Statutes in pari materia: in pari materia with each other if they are so

Sind tocech other as vor a system or code of legislation in respect of a

rel

amen fener in US. v/s Bagle Bank has explained the phrase ‘pari materia’

in the following words:

“Statutes are in pari ie

orto the sania Pe which relates to the same person or thing,

nt be confounded a a or things. The word ‘pari materia’ must

intimating not likenewe Mes ‘similar’. It is used in opposition to it

public statute or 7 Identity. It is a phrase applicable to the

eneral laws i i i

the same subject matter, made at different times & in reference to

Thus, all statutes dealing with licensi

: AS, 4 ig with licensing of solicitors hi

te Pie Davis v/s Edmondson (1803). Two aie piltnetrehibaes

962) ing were considered in pari materia in Bolton Corp. v/s Owen

However, it is not necessary that the entire subject m:

saa atter

ise baie Thus in State of Madras v/s Vaidyanath Aiyar cane

lefinition of expression ‘shall presume’ contained in Indian Evidence Act, 1872

has been considered to be in pari materia with the expression ‘it shall be

presumed’ in Section 4 of Prevention of Corruption Act, 1947. The two

provisions were considered to enact rules dealing with the same subject matter,

viz. burden of proof.

Where an earlier statute is repealed & substituted by another statute which

reproduces the language used in earlier statute. The two statutes are considered to

be in pari materia. Thus in Bengal Immunity Co. v/s State of Bihar (1955),

Articles 245 & 246 of the Constitution was pari materia with Sections 99 & 100

of Government of India Act, 1935. This presumption arises very strongly in case

of consolidating statutes, as they prima facie do not intend any change of

intention.

The Doctrine of pari materia cannot apply where the legislature have a

different scope. In State of Punjab v/s 0.G.B. Syndicate (1964), it was held that

the Displaced Persons Debt ‘Administration Act, 1948 was not in pari materia

with the Act of 1964 because the 1964 Act had a larger scope & was designed to

secure greater advantages to displace person than the 1948 Act.

Statutes in pari materia are to be taken as forming one system. Lord

Mensfield has laid down the rule in R. v/s Loxdale (1758) that statutes in pari

materia are to be considered together irrespective of the fact that they have been

enacted at different times or do not refer to each other or even if some of them

have expired. Aforesaid principle has been accepted in India & has been applied

in large number of cases. Thus, in Vidyachand v/s Khubchand (1960) SC held

that the Limitation Act, 1963 & C.P.C., 1908 were in pari materia with each other

& must be considered as a single system.

2) Assistance of earlier statutes dealing with the same subject matter: aid the

language of the statute is ambiguous a comparison may be made with the ire

language of earlier statutes relating to the same subject matter. This princip!

many manifestations:

@ if ‘a statute, upon which a particular construction has been rel . id cor

in the past, is re-acted in the same language, it is presumed that the | fa aie

jntends no change in the meaning. However, solitary decision, particularly

not of the highest Court cannot give rise to such a presumption.

i fed connotation of the expressi

in Vijraveh Hector, A

sc 1017's ij lu Mudiliar

along time,

Misa tw ein ‘has defined certain expressions in one statute it is

a ‘€xpressions carry the same meaning if they are used in the later

Statutes dealing with the same subject matter. In Knowles Itd. v/s Rand (1962), it

was held that the expression ‘agricultural land’ in Agriculture holding Act, 1948

‘was given the meaning assigned to it in the Agricultural Act, 1947,

(iv) Where a single section of an earlier Act is incorporated by reference in a later

statute, it has been held in Portsmouth Corp. v/s S. Smith (1885) that the

Section is to be read in the sense it bore in Parent Act.

Where, however, the whole of earlier statute or parts of it are incorporated

in the later statutes, the incorporation has been held to cause a bodily

‘transportation of such provisions from the earlier to the later enactment. A repeal

or the amendment of the earlier statutes does not affect the provisions

incorporated in the later Act.

.

3) Assistance of later statutes: Normally a later statute cannot be used as an aid to

the construction of earlier one. However, certain exceptions are recognized:

a) Where the later statutes seeks to amend an earlier statutes or the

meaning of such earlier statute.

b) Where the provisions of an earlier Act are ambiguous. It may be

construed with reference to a later statute provided that the later statute is on the

same subject & is itself free from ambiguity. . :

‘When an earlier Act is truly ambiguous, a pry ie may in certain

i varliamentary exposition of the former.

can SVP. Cement Co, vis General Mining Syndicate (1976), the SC held

that a subsequent statute which amends a Parent Act to clarify it, amounts to a

parliamentary exposition,

4. Contemporanea Expositio: Lord Coke firstly laid down the principle of =

Contemporanea Expositio with reference to the Magna Carta, According to “a

ancient grants statutes must be construed with reference to the law as it was al

time when the statute or grant was made. Such Contemporanea Expositio may emerge

out of long professional usage or judicial decisions.

i th took into account the

Thus, in Ohlon’s case (1891), the Court of Queens Bencl

practice followed by Inland Revenue Commissioners for the past 16 years. InR. wis

of jud; is 7

ne question whether the Courts had the Was taken ‘Into consideration for determining

convict. © Power to im i

The toon FA pose consecutive sentences on

'¢ of Contemporane: iti

In Clyde Navigation Trustees Wf Leto has no application to modem statutes.

Navigation Consolidation Act, 1856 i ed Neti do arent the Clyde

the river Clyde. Such tas NU 16 imposed ‘Navigation tax on the timber floated on

placed on the u fo Xx Was paid Without protest from 1858 to 1882 & reliance was

practice relevant a i Supporting the levy. Lord Watson refused to consider the

ata, ground that the doctrine had no application to a modern

This view of Lord Watson has beet i

n affirmed in by the He i

Campbell College vis Commissioner (1964). ee

lia, as refused to follow the doctrine of Contemporanea Expositio wi

f positio with

Tespect to Evidence Act, 1882 in Raja Ram v/s State of Bihar (1964) & to the

Telegraph Act in Senior Electric Inspector v/s Laxmi Narayan on the ground that

the statutes had no application to moder statutes.

5. Dictionaries: Dictionaries can be resorted to, as aids to interpretation on the

principle that the words used in the statutes should be taken to be used in their

ordinary sense. uw

In Re Ripon Housing Order (1939), the word ‘park’ had interpretedjits ordinary

meaning in accordance with Oxford Dictionary.

In India, dictionaries are referred to on the same principle. Thus, in Aziz Pasha

vis UOI (1967), SC gave the expression ‘establighed? in Art. 30(1) of the Constitutio

in its dictionary meaning & held that the A.M.U. was not established by a minority.

In State of Orissa v/s Titagarh Paper Mills Co.Ltd AIR 1985 SC, held &

observed that the dictionary meaning of a word can’t be looked at where that word

has been statutory defined or judicially interpreted.

You might also like

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5811)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Project Report On The Concept of Rule of Law: University Institute of Legal StudiesDocument30 pagesProject Report On The Concept of Rule of Law: University Institute of Legal StudiesKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- 921 1 01 Adv CommanderP1 SR First Officer P2 First OfficerDocument11 pages921 1 01 Adv CommanderP1 SR First Officer P2 First OfficerKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Before: (Under Art. 136 of The Constitution of Asnard)Document31 pagesBefore: (Under Art. 136 of The Constitution of Asnard)Khalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Plagiarism in Legal Research: Why Should We Care?Document21 pagesPlagiarism in Legal Research: Why Should We Care?Khalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Content WritersDocument1 pageGuidelines For Content WritersKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

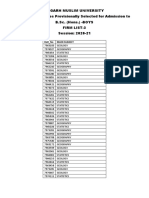

- Aligarh Muslim University List of Candidates Provisionally Selected For Admission To B.Sc. (Hons.) - BOYS Firm List-3 Session: 2020-21Document7 pagesAligarh Muslim University List of Candidates Provisionally Selected For Admission To B.Sc. (Hons.) - BOYS Firm List-3 Session: 2020-21Khalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Growing Problems With Nri MarriagesDocument11 pagesGrowing Problems With Nri MarriagesKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Appointment of Arbitrator S.11 and Trends PDFDocument8 pagesAppointment of Arbitrator S.11 and Trends PDFKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- CEDAWDocument1 pageCEDAWKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Minority Women's Right Tosuccession and InheritanceDocument14 pagesMinority Women's Right Tosuccession and InheritanceKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Appointment of Arbitrator S.11 and Trends PDFDocument8 pagesAppointment of Arbitrator S.11 and Trends PDFKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Hindu LawDocument2 pagesHindu LawKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Types of FeminismDocument21 pagesTypes of FeminismKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Writing A Good Research ArticleDocument17 pagesWriting A Good Research ArticleKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Growing Problems With Nri MarriagesDocument11 pagesGrowing Problems With Nri MarriagesKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Taxation C 1Document4 pagesTaxation C 1Khalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Environmental Law Sustainable Development DR - GYAZDANIDocument77 pagesEnvironmental Law Sustainable Development DR - GYAZDANIKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Rights of Daughters As CoparcenersDocument2 pagesRights of Daughters As CoparcenersKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- Company Law Unit-3Document18 pagesCompany Law Unit-3Khalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- EBC - Tabulation of Webinars, 16apr2020Document3 pagesEBC - Tabulation of Webinars, 16apr2020Khalil AhmadNo ratings yet

- References: (A) Constitution/ActsDocument7 pagesReferences: (A) Constitution/ActsKhalil AhmadNo ratings yet