100% found this document useful (1 vote)

631 views15 pagesAdapting Classroom Materials

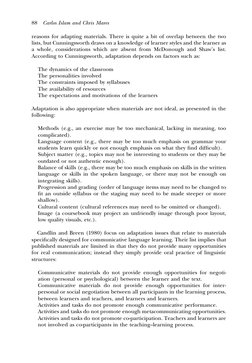

This chapter discusses adapting classroom materials. It provides several reasons why teachers may need to adapt materials, such as the materials not fully reflecting communicative language teaching principles, having inappropriate content or level, or not accommodating different learner needs and styles. The chapter then discusses objectives for adaptation, such as personalizing materials to students or local context, and provides techniques for adaptation, including adding real choices for students in their learning. Overall, the chapter advocates that adaptation of materials is important to make them as effective as possible for each unique classroom context.

Uploaded by

Thảo NhiCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd

100% found this document useful (1 vote)

631 views15 pagesAdapting Classroom Materials

This chapter discusses adapting classroom materials. It provides several reasons why teachers may need to adapt materials, such as the materials not fully reflecting communicative language teaching principles, having inappropriate content or level, or not accommodating different learner needs and styles. The chapter then discusses objectives for adaptation, such as personalizing materials to students or local context, and provides techniques for adaptation, including adding real choices for students in their learning. Overall, the chapter advocates that adaptation of materials is important to make them as effective as possible for each unique classroom context.

Uploaded by

Thảo NhiCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

We take content rights seriously. If you suspect this is your content, claim it here.

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online on Scribd