Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Ancient Philosophers On Language in Col PDF

Uploaded by

Jo GaduOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Ancient Philosophers On Language in Col PDF

Uploaded by

Jo GaduCopyright:

Available Formats

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

Ancient Philosophers on Language

From the Pre-Socratics to the Neoplatonists, ancient Greek philosophers formulated their approaches

on language by focusing, in part, on the relation between language and reality. Their reflections on the

‘natural’ or ‘conventional’ character of language resulted in both extreme and moderate views

concerning the phenomenon of linguistic expression. Philosophical thought later turned to the way

that spoken sounds represent things via concepts, constructing the first semiotic triangles.

Reflection on language is intrinsically related to the concept of philosophy itself, since

it is only via language that statements about reality and knowledge can be

communicated. From the origins of Greek philosophy in the 6th c. BCE to the end of

antiquity, conventionally dated to the 6th c. CE, linguistic thought is constantly

present, as testified by the surviving texts.

The discussion of language in the Greek philosophical tradition addresses linguistic

issues that remain crucial even today. Contemporary historians of linguistics estimate

that in philosophical texts of antiquity there can already be traced speculations that

are examined by independent fields of contemporary linguistics, such as phonology,

morphology, semiotics, semantics and pragmatics.

However, the evaluation of the linguistic approaches formulated by the philosophers of

antiquity is a priori obstructed by an important restriction, which renders any possible

answers to queries on specific research in this area rather relative. The texts, for

instance, written by philosophers during the Archaic age (6th/5th-c. BCE) and also by

the Sophists (5th-c. BCE), as well as by the Hellenistic philosophers (323-31 BCE), are

almost completely lost. With the exception of a few cases of direct tradition, our

knowledge of these philosophers’ views on language is based on indirect tradition: (1)

on a few verbatim fragments, which are mostly given ‒ out of their context ‒ by

authors who often lived centuries later than the thinkers and works they refer to and,

most of all, (2) on ancient evidence and doxographic information. Therefore,

concerning the ‘origins’ of ancient philosophers’ thoughts on language, when reflection

on language was not the purpose of philosophy in its own right, but also during the

Hellenistic age, when language research became a separate discipline (particularly

through the Stoic theories), our views are based on scholars’ reconstructions ― which

are far from agreeing with each other (→ → Philological-Grammatical Tradition in Ancient

Linguistics).

On the other hand, we are lucky enough to have at our disposal the corpus of Platonic

dialogues, which contains the first text focusing on language that survives in its

entirety, namely, the Cratylus. Aristotle’s didactic writings also survive, in which we can

trace several approaches that consider the phenomenon of linguistic expression from

various aspects. Finally, a series of commentaries on Plato and Aristotle survive,

written by philosophers of Late Antiquity; since they comment on the linguistic

approaches of the two thinkers, these scholars ― apart from formulating original and

1 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

interesting views ― combine and adjust various linguistic approaches of antiquity

from their ‘origins’ up to the scholars’ own era.

While attempting to present the Greek philosophers’ views on language, apart from the

chronological factor, one should take into account a thematic approach ― to the

extent that this is possible ― given the fact that these views follow a kind of sequence,

in the sense that they presuppose knowledge and are often a ‘reaction’ to the views of

their antecedents.

1. Pre-Socratic Philosophers

( múthos)

1.1 The ‘Origins’: from Myth (múthos ( lógos)

múthos ) to Reason (lógos

lógos )

Insofar as excerpts from the ‘first philosophers’ (the ‘natural philosophers’) allow us to

make some assumptions about their kind of contemplation on language, it is almost

clear that this reflection was not undertaken for its own purpose, but rather served the

need to examine the extent to which non-linguistic reality can be expressed via

language.

The formulaic phrase ‘from myth (múthos) to reason (lógos)’ represents for scholars the

‘origins’ of philosophy, that is, the emerging tendency to approach reality in a way

different from that suggested by the epic poetry of Homer and Hesiod, the ‘tutors of

Greeks’ (see Xenophon 21B10 DK; Heraclitus 22B57 DK; cf. Pl. Resp. 606e). While there

was no linear development from myth to reason (see Buxton 2001), the old

mythological/theological explanation of cosmos did give way to a new, conceptual

approach based on argument, critical inquiry and evidence. Phúsis is at the very center

of this inquiry and is explained through itself, by the use of physical terms instead of

assumed actions by personalized human-looking creatures (“Indeed not from the

beginning did gods intimate all things to mortals, But at length, as they seek, they

discover better”: Xenoph. 21B18 DK; cf. Lesher 1992:27 and 149-155). This

differentiation from the poet-tutors and the popular mythological tradition, along with

the tendency of philosophy to re-establish itself, led to criticism of the linguistic use of

anthropomorphized natural forces (Morgan 2000:30ff.), which reflected a distorted

concept of cosmos. While attempting to obtain a distinct identity by communicating a

new vision of reality, philosophy at its origins attacks poets and their reality.

A famous fragment by Xenophanes reveals in the most telling way the character of this

altered philosophical orientation, distanced from the mythological explanation

formulated by the poets and reflected in their linguistic use: the poetic ‘messenger of

gods’, Iris, (cf. Hom. Il. 17.547) is nothing but a multicolored cloud (Xenoph. 21B32 DK;

cf. also Α39 DK). The philosophers’ criticism goes beyond that and also attacks the

current spoken language, as they consider it inadequate to conceive of and render

reality ― something that philosophy can definitely achieve.

Among Heraclitus’ (544-484 BCE) oracular sayings, two seem to mainly denote that in

his view, language represents reality only in part (see Kirk 1954:48, 118), and in this

2 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

sense language is ‘insufficient’. In his theory, cosmos is ruled by the principle of ‘the

unity of opposites’ (coincidentia oppositorum). For example, life and death are two

aspects of one singular reality. Therefore, one of the Greek words signifying the ‘bow’

(tóxon), the word biós, refers to the word bίos, the Greek word for ‘life’: “The name of the

bow (tóxon) is life (bíos), its work is death” (Heracl. 22B48 DK). The second fragment may

be explained in the same way (Heracl. 22B32 DK): Zeus, whose name in genitive (Zēnós)

refers to ‘life’, “wishes and does not wish to be called with it.” This means that the

god’s name is only partly informational and therefore partly misleading. Taking for

granted that beneath our human ways of speaking there exists a true nature that

“loves to hide itself” (Heracl. 22B123 DK; see Nussbaum 2001:241), language is only a

pretext for further inquiry: besides, “The Lord, whose is the Oracle at Delphi, neither

speaks nor hides but gives signs, signifies (sēmaίnei)” (Heracl. 22B93 DK). The decisive

meaning of the verb sēmaίnein could be revealed by Heraclitus’ lógos.

However, also according to the philosophers who represent ancient Western

philosophical thought, as opposed to the philosophers of the East (Ionian philosophers,

Socrates, Plato, Aristotle, etc.) and of Southern Italy (Eleatic philosophers such as

Parmenides (c. 490-430 BCE) et al., and Empedocles (c. 495-435 BCE)), ‘names’ (= words)

that people use with the conviction that they represent truth are actually false ‘names’,

because they refer only to the surrounding phenomena and testify to an underlying

ignorance of reality’s true nature. For Parmenides, the names imposed by mortals

(katéthento; see section 2.2 below; 28B 8.34-41, 53-9, 9.1 DK / 28B8.38–41; 28B19 DK) are

false because they simply represent opinions (dóxa), and not truth (alḗtheia) and ‘being’

(ón) (see Sluiter 1990:170; Barney 2001). Similarly, the words ‘birth’ and ‘death’ in the

ordinary vocabulary are used by Empedocles to denote the actual procedures of

‘mixing’ and ‘separating’ the elements, the four rhizṓmata (earth, water, air and fire);

however, he adjusts himself to their law and convention (nómos) (see Emp. 31B9 DK; cf.

fr. B10 DK).

1.2 The Sophists

The Sophists belong to the broader category of the so-called Pre-Socratics (according

to Diels’ classification), and their orientation and scope were completely different from

those of the philosophers discussed so far. The Sophists emerged during the second

half of the fifth century, acting mainly as wandering tutors; it was the age of Athenian

democracy, and the study of linguistic usage was necessary for purposes of rhetoric

and argumentation. These philosophers’ interest in language is variably testified in

sources, particularly by Plato and Aristotle, although the lack of original texts makes

an accurate evaluation of their linguistic concerns difficult. Issues that puzzled two of

the most prominent Sophists, Protagoras (fl. 444 BCE) and Prodicus (fl. 400 BCE), were

the ‘correctness of diction’ (orthoépeia; Pl. Phdr. 267c), which is possibly connected to

poetic linguistic use (Guthrie 1998, 3:205), and the ‘correctness of names’ (orthόtēs tôn

onomátōn; cf. Pl. Crat. 384b, 391c; Euthd. 277e; → Linguistic Correctness (hellēnismόs),

Ancient theories of), which is most likely a reflection upon the connection between

words and things they denote (see section 2.2 below).

3 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

The evidence is richer concerning Protagoras’ views, and this evidence could establish

Protagoras as “the parent of all subsequent study of language ‒ including logic,

grammar, linguistics and semantics” (Schiappa 2003:162). Protagoras traces two ‘errors’

committed by Homer, even in the first two verses of the Iliad: the false use of the

imperative instead of the optative (Aristot. Poet. 1456b15), and the use of the feminine

grammatical gender for a word denoting a ‘male’ attribute (mênis ‘wrath’; he argues the

same about pêlix ‘helmet’; Aristot. Soph. el. 173b17-22). The Protagorean distinction

between grammatical and natural gender seems to be reflected in the parody of

Aristophanes’ Clouds (659-691) through the example of alektruônos/alektruainēs.

According to Aristotle (Rh. 3.5.1407b6 = Prt. 80A27 DK), it was Protagoras who

distinguish the genders of names as being ‘masculine’, ‘feminine’ and ‘those referring

to inanimate objects’, and he was also the first to distinguish what are today called

‘speech acts’ (puthménas lógōn). At the same time, what is mainly testified concerning

Prodicus’ practice towards language is the ‘division of names’ (diaίresis tôn onomátōn;

see Pl. La. 197d; Chrm. 163d), meaning the subtle semantic distinctions between what is

called today ‘near synonyms’: thus, he distinguished, e.g. among ‘pleasure’, ‘delight’,

‘enjoyment’ and ‘gratification’ (Aristot. Top. 2.6 = 122b; = Protagoras 80A19 DK; cf. Pl.

Prt. 358a6-b 2; Alex. Aphr. in Top.181.1-6; see Mayhew 2011:124-31), possibly aiming at

accuracy and, furthermore, at correcting the current linguistic use (Ademollo 2011:28).

(phúsei)

2. Is Language ‘By Nature’ (phúsei

phúsei ) or ‘By Convention’

(nómōi)?

nómōi )?

2.1 The Sophists

The Sophists seem to have applied the ‘nature vs. convention’ controversy to the

reflection on language. This famous debate was dominant during the second half of the

5th c. BCE in fields such as ethics, politics, etc. When it comes to language, this

particular contradiction focuses on the relation between words and things: is this

relation natural, in the sense that ‘names’ (= words) reveal the nature and the

attributes of their referents (‘naturalism’) or are names wholly arbitrary impositions on

objects, the outcome of convention among various linguistic communities

(‘conventionalism’)? Apart from the term nómōi (‘by law/custom’; cf. Empedocles above

and Democritus below), conventionalism is also expressed by the terms éthei (‘by

habit’), sunthḗkēi (‘by contract’), homologίai (‘by agreement’; see Pl. Crat. 384d), katà

sunthḗkēn (Aristot. Int. 16a19), and finally it was the term thései (‘by imposition’; see

Epicur. Ad Herod. 75.7) that prevailed.

Plato’s Cratylus, which has the subtitle “On the correction of names”, explicitly relates

the ‘nature vs. convention’ debate to the Sophists, making specific references to

Prodicus (Crat. 384b) and to the Sophists in general (Crat. 391b), alongside explicit

discussion of Protagoras (Crat. 385e, 391c; cf. Phdr. 267c). Despite the fact that this

dialogue systematizes and represents the reflection of previous thinkers, constituting

our main source of information on some basic parameters of the specific contradiction

4 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

of ‘nature vs. convention’, under no circumstances should this dialogue be considered

as ‘documentary’: the issue of the ‘correctness of names’ is discussed in service to

Plato’s approach to language, which considers words, in their variety, inadequate to

directly render the eternal and uncorrupted idea (Pl. Crat. 398e). Besides, the dramatic

personality of Socrates is clearly distanced from sophistic approaches (see Ademollo

2011:28).

With the exception of Cratylus himself, there is no evidence for pre-Platonic

philosophers who could be adherents of the ‘by nature’ approach. However, this

particular approach seems to have its origins in the tradition of Homer and Hesiod (cf.

also Pl. Crat. 391c-393b). In Hesiod’s Theogony, the nature and the attributes of a deity

are explained via the etymology of the corresponding name; similar examples also

appear in Aeschylus and Euripides (see Liebermann 1996; Schmitter 2000:347-351;

Ademollo 2011:34), as well as in the famous → Derveni papyrus, where divine names are

explained this way (beginnings of 4th c. BCE; see, e.g., col. XIV, XV: Cronos; XXII:

Dēmḗtēr).

Etymology, i.e. the unfolding of words through which their true meaning is clarified

(see Schol. Dion. Thrax, 14.23-24 Hilgard), was a widespread practice during the age of

the Sophists (see Barney 2001:66-67), which constituted the primary tool used for the

clarification of the words’ original ‘forms’; this practice rendered the actual features of

what was named and, consequently, shed light on the ‘natural’ relation between names

and things. It is worth saying that the Stoics’ valuation of etymology is reflected in

their belief that the ‘first words’ imitated things (see Allen 2005; see also Stoic

etymologies in FDS 650-680 Hülser).

2.2 Democritus

However, concerning the ‘by convention’ approach, Proclus gives evidence that it was

supported by Democritus, who was a contemporary of both the Sophists and of

Socrates (Procl. in Cra. 16.23-47 Pasquali = Democr. 68B26 DK). Democritus defended his

view on the basis of four arguments: 1. Different things bear the same name

(‘homonymy’; Democritus’ term was polúsēmon); 2. Different names are used for one and

the same thing (‘polyonymy’; Democritus’ term was isórropon ‘balanced’); 3. Names can

change (‘transposition of names’; Democritus’ term was metṓnumon); 4. There are cases

where language does not have derivatives in comparison to others (‘lack of the same’,

élleipsis tōn homoίōn; Democritus’ term was nṓnumon).

Proclus has often been questioned by scholars as a reliable source, given his

chronological distance from Democritus. However, in spite of the possibility that the

term thései (‘by imposition/convention’) is Proclean (Democritus himself most probably

used the term nómōi ‘by law/custom’ to denote conventionalism, as is quite evident in

the famous fragment Democritus 68B9 DK, “because by law, he says, sweet and bitter,

by law hot and cold…”), Proclus also uses the terms ‘homonymy’ and ‘polyonymy’, etc.

as equivalents for terms formulated and used by Democritus (see above). Furthermore,

some of the arguments attributed by Proclus to Democritus apparently belonged to the

5 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

standardized supportive material of the ‘by convention’ approach: for instance, the

‘transposition of names’ is used in Plato’s Cratylus by the supporter of conventionalism,

who is Hermogenes.

2.3 Cratylus

The subject in Plato’s Cratylus is, as stated in the work’s subtitle, the ‘correctness of

names’, for which two opposite theories are proposed and discussed. Cratylus claims

that names are correct ‘by nature’, in the sense that words reveal the substance of

things named (Pl. Crat. 383a-384c). However, according to Hermogenes (384c-386e),

names are exclusively the outcome of convention within and among linguistic

communities. Hermogenes is led further to the extreme edge of conventionalism,

supporting even the correctness of a ‘private language’, in contrast to the ‘public

common speech’ (385a: idíai-dēmosíai; 385d-e). It should be noted that although Cratylus

is considered ‘Heraclitean’, he does not necessarily represent the approach to language

formulated by Heraclitus himself (see Kirk 1954:119-120), who believed that language

can only partly render reality. Socrates, who attempts to mediate between the two

opposite views supported in the dialogue by Cratylus and Hermogenes, examines both

in a critical way, tracing their questionable points and concluding that the ‘by nature’

and ‘by convention’ approaches complete each other.

In his arguments defending the ‘by nature’ approach, Socrates exploits its typical tool,

etymology, in an extended section of the dialogue which is most often characterized as

parody or joke (for an opposing view, see Sedley 2003, 2006; Ademollo 2011:237-241).

Socrates aims to prove that the meaning of words remains the same despite differences

resulting from linguistic change and owing to linguistic diversity: current words are

traced back to the ‘first (= original) names’, which cannot be deconstructed any further.

Concerning the natural character of the specific ‘first names’, Socrates resorts to a

supplementary argument (Pl. Crat. 423b4ff.), which is ‘phonetic naturalism’ (see Long

2005:43): this, put briefly, focuses on the imitating power of words as expressed by the

imitative potential of a word’s phonetic elements, its simple phonetic sounds (=

‘phonemes’, in contemporary terminology); these phonetic elements are considered as

“phonetic similes of basic qualities things have, such as liquidity, stability, harshness,

magnitude, etc.” (Sedley 2006:220). In the end, this second argument is rejected, and so

is etymology as a method to access knowledge, while, at the same time, the role of

convention is acknowledged.

The conclusion is that although words function to “teach and distinguish reality”

(388b13-c1), they do not reflect things and reality’s structure after all, but rather they

express the name-giver’s (onomatothétēs) concept of the world. Therefore, one should

not give much credit to words, but investigate things themselves instead

(438d2-439b9).

2.4 The Origins of Language

In a different way, only indirectly related to the above opposition, Epicurus and

6 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

Epicureans dealt with the debate of ‘nature vs. convention’, applying the dimension of

‘nature’, used elsewhere in considering the correctness of words, to examine the

origins of words (see Epicur. Ep. ad Herod. 75-6; cf. Lucr. 5.1028-90 and Diogenes

Oenoandensis, 12.2.11-5.14 Smith).

Although evidence suggests that all the philosophers before Epicurus (regardless of

whether they considered the correctness of names as natural or not) took the

imposition (thésis) of names for granted (see, e.g., Pl. Crat. 390d: thésis tôn onomátōn;

397c, 401b; see also 388e-389d: nomothḗtēs, onomatothḗtēs/-ai; cf. also section 1.1 above,

on Parmenides), Epicurus himself rejects the view that language was created ‘by

imposition’ (= thései) and adopts two distinctive stages that concern: 1) the origins and

2) the evolution of language:

1. The origins of language were natural as belonging to human nature (like voice,

vision and hearing; fr. 335 Usener), and also as a reaction to emotions and

impressions, occurring differently in each tribe. Each emotion or impression led

to a peculiar exhalation of breath, in accordance with the different location of

each tribe (Epicur. Ep. ad Herod. 75).

2. The evolution of language, the second stage of its development, occurred in each

tribe when the factor of a common agreement (koinôs) is brought in so that there

can be clarity and accuracy to facilitate verbal communication. This stage seems

to also include the introduction of new words by those ‘savants’ who conceive of

the existence of ‘non-existing’ or abstract things that are not perceived by most

people (polloί; Bailey 1980:1487 claims that this is a third stage).

3. The Semiotic Triangles

The common term ‘semiotic triangle’ is used in contemporary semiotics and linguistics

(after Ogden & Richards 1923:11) to refer to the tripartite structure of the linguistic

sign, that is, to the use of three units for the needs of sēmeίōsis, one of which is the

medium between the other two (Manetti 1993:94). This ‘semiotic triangle’ has its origin

in Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics.

3.1 Plato, Cratylus

The conclusion reached by Socrates in Plato’s Cratylus implies that names do not

illustrate the nature of things after all, but express the name-giver’s concept of the

world (438aff.). Consequently, there relation between a name and what it names is not

direct: rather, a name declares a subjective representation (= meaning) of a thing (see

Manetti 1993:63; see also Oehler 2006:135ff.).

3.2 Aristotle, On Interpretation

Aristotle is considered by ancient ‒ and, partly, by contemporary ‒ scholarship to have

given a clear answer to the ‘nature vs. convention’ debate discussed in Plato’s Cratylus

(see, for example, Dalimier 1998; Struck 2004:83; van den Berg 2008). In Aristotle’s On

7 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

Interpretation, spoken sounds (Aristot. Int. 16a4-9: tà en têi phōnêi), words (16a26-28:

onómata) and speech (17a1-2: lógos) are said to be ‘symbols’, ‘signs’ and ‘by convention’

(see Weidemann 1991:179ff.; Ax 2000:32-33; also Arens 2000:367-368).

Scholars trace the first attempt for a ‘semantic/semiotic’ approach of language, the

first semantic theory on interpreting thoughts by means of words, to the famous

Aristotelian ‘semantic passage’, the text with the greatest influence in the history of

semantics/semiotics (see Kretzman 1974:3; Irwin 1982; Weidemann 1991:170-173 and

176ff.; Manetti 1996; Sedley 1996; Verbeke 1996; Ax 2000:59-63; Arens 2000:367-370;

Modrak 2001:1). Aristotle is considered to have initiated the ‘structuralist’ approach to

language, which is the opposite of functionalism (see Givόn 2001:4). The philosopher

epitomizes the relation between experiential data, mental/psychological states and

language. Aristotle’s belief is that words function as symbols, according to the

conventional way decided by the members of a linguistic community, and that they

signify things via the soul’s pathḗmata, which are the ‘first meanings’ (noḗmata) formed

by the figurative impressions of things, after their sensory perception (see Ax 2000, and

also Weidemann 1991):

“Now spoken sounds are symbols of affections in the soul, and written marks symbols of of

spoken sounds. And just as written marks are not the same for all men, neither are

soull – are

spoken sounds. But what these are in the first place signs of – affections of the sou

the same for all; and what these affections are likenesses of – actual things – are also

a lso the

same” (Arist. Int. 16a4-9, transl. Ackrill)

Ackrill )

Aristotle discusses two levels of ‘semantic’ relations: the first one involves vocal sounds

and mental/psychological states, and the second one involves these states as well as

experiential data, which are neither linguistic nor mental. These three units and their

interrelations form a rather clearly schematized ‘semantic triangle’ (see Manetti

1993:72) and attract the attention of linguistics, psychology, semiotics and logic. The

terms of this text that are considered to epitomize the first attempt towards a

semantic/semiotic approach towards the phenomenon of linguistic expression and

which, at the same time, constitute the three angles of the famous Aristotelian

semantic triangle are the following:

1. ‘Things’ (prágmata) are perceived through senses.

2. The ‘affections of the soul’ (pathḗmata tês psukhês) are the mental states that

follow sensory perception and are formed before linguistic expression; they are

called ‘likenesses’ (homoiṓmata) of things.

3. Vocal sounds (tà en têi phōnêi/taîs phōnaί) follow the formation of the ‘affections of

the soul’, of which they are called ‘symbols’ and ‘signs’. (A fourth term, ‘those that

are written’ (tà graphómena), concerns the graphic representations of spoken

sounds).

The ‘affections of the soul’ are the soul’s mental states (= thoughts) ‒ as noûs belongs to

the Soul according to Aristotle ‒ which means that they are the ‘affections of the

8 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

mental soul’ (see Weidemann 1991). More specifically, they are the ‘first

thoughts/concepts’, formed on the basis of figures that are modeled on imprints

(phantásmata) left in the mind by the sensory perception of things. These ‘affections’

are naturally related to things and are called their ‘likenesses’. So far, the first level of

the semantic passage concerns a natural procedure:

pathḗmata tês psukhês (affections of the soul, ‘first meanings’)

tà en têi phōnêi/taîs phōnaί (vocal sounds) prágmata (‘things’)

The vocal sounds represent things as ‘symbols’ and ‘signs’, and they are conventionally

connected to the ‘affections of the soul’: despite the intensive and controversial

discussion among scholars concerning the possible differentiation between the terms

súmbola and sēmeîa, Aristotle seems to use both terms rather indistinctively, and in

general he formulates the view that things are expressed and represented via

articulate vocal meaningful sounds, which are names (onómata), verbs (rhḗmata),

assertions, negations and, generally, via what the term tà en têi phōnêi comprises (see

Weidemann 1991; Arens 2000). He expresses the view that speakers of the same

language can communicate their thoughts and ideas by means of their vocabulary and

thus can refer to the same things. What is more, in On Interpretation, Aristotle not only

explicitly refers to the three constituents of signification, which are ‘things’, ‘mental

activity’ and ‘linguistic expression’, but he also implies a distinction between

reflexive/direct expression and language.

3.3 The Stoics

After Aristotle, the Stoics claimed that names are ‘by nature’ and their views have

many similarities with those expressed by Cratylus (for the influence of the Platonic

dialogue on the Stoics, see Barwick 1957:70-79). However, the Stoic semiotic triangle is

considered to be a development of the Aristotelian one.

Our main source for the specifically Stoic approach is Sextus Empiricus (Sext. Emp.

8.11-12). Starting from the basic distinction between unarticulated phonetic matter and

structured linguistic form, as formulated by Aristotle (Aristot. Hist. an. 488a31-32,

535a30-31; PA 659b27-30; An. 420b12ff.; Int. 17b13-17), the Stoics schematize the act of

signification using the terms ‘what is signified’ (tò sēmainómenon) in the vocal sounds

(phōnḗ), which is also a concrete state of affairs (autò tò prâgma), ‘that which signifies’

(tò sēmaînon) and the object of reference (tò tunkhánon). These three units are linked

with each other: the spoken word indicates what is signified and the object of reference

is the existing thing itself. What is unique in this approach is that the ‘state of affairs’ is

not a ‘body’ (in Stoic theory, ‘bodies’ are not only material substances, but also

qualities and several states), but a ‘sayable’ (lektón), which is either true or false. The

Stoic approach thus contains:

sēmainómenon (signified)

lektón (sayable)

9 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

sēmaînon (signifier)

tunkhánon (existing object)

Lektón is what exists in phantasía and can be expressed in words (Diog. Laert. 7.63.5-6

Long = von Arnim, SVFII.181 = Hülser 696; Sext. Emp. 8.69.6-8 = von Arnim, SVFII.187 =

Hülser 326). This term concerns the “sense of significant discourse” (see Sedley

1996:94), the semantic realization itself. The Stoic ordering of lektá is one of the crucial

linguistic approaches in ancient Greek thought. The earlier surviving source about lektá

is Diocles of Magnesia in the so-called ‘Diocles fragment’, preserved in Diogenes

Laertius (7.66 Long; on lektá see in general Long 1986:131ff.; Egli 1986; Frede 1987:343ff.;

Householder 1994:217).

4. Neoplatonic Commentators on Aristotle: Ammonius (of

Hermeias)

The Neoplatonic commentaries on Aristotle belong to the long commentatory tradition

inaugurated by Plotinus, when philosophy began to be identified with commentating

the writings of the two great thinkers. These philosophers’ exḗgēsis is directed in

accordance with the crucial ‘principle of agreement’ between Plato and Aristotle (see

Karamanolis 2006): it is the commentators’ belief that reading Aristotle (Plato’s best

‘student’) contributed to the deepest understanding of Plato’s philosophy (see Kotzia

2007:194-201).

4.1 Language is Both ‘By Nature’ and ‘By Convention’

Ammonius, son of Hermeias (end of 5th- beginning of 6th c.; see Blank 1996:1), the

student of Proclus in the Athenian School (founded by Plutarch of Athens; it was closed

by Justinian’s order in 529 CE: see Beaucamp 2002; Sorabji 2005:9), was the Head of the

School in Alexandria (see Sorabji 1990:1-30; Westering, Trouillard and Segonds

2003:x-xlii; Blumenthal 1993:307-325). Ammonius’ commentary on Aristotle’s On

Interpretation is the only surviving Greek Neoplatonic commentary on that ‘linguistic

text’ of antiquity; Proclus (whose commentary on Plato’s Cratylus survives) commented

on it but did not publish his commentary.

When commenting on Aristotle’s ‘semantic passage’ (see section 3.2 above), Ammonius

exploits the Socratic distinction between the ‘creation’ and the ‘use’ of a name (see Pl.

Crat. 389a2ff. 390c10-11), as well as the concept of the Platonic ‘name-giver’ (see section

2.2 above), in order to explain Aristotle’s characterization of onómata as súmbola:

according to Ammonius, the name-giver is thoroughly aware of the nature of a thing,

and he thus imposes the appropriate name. This means that a name is katà sunthḗkēn

(‘by convention’) as Aristotle claims, but only from the point of view of its ‘imposition’,

as well as its later established use by the members of a linguistic community (Ammon.

in Int. 35.17ff.). However, since this imposition takes place according to the knowledge

of the nature of things, the name is also an homoίōma (‘likeness’), not a natural one, but

one katà tékhnēn (‘according to some art’; for the term tékhnē in name-giving see Pl.

10 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

Crat. 389a2, 390e1-4, 393d4; see also Procl. in Cra. 123.1-6). For Ammonius, the terms

homoíōma katà tékhnēn and súmbolon are not incompatible, because when a name is

imposed without aiming at genuinely representing a thing, then it is imposed askópōs

(‘without any purpose’) and it is a simple súmbolon; nevertheless, when it is imposed

‘according to reason’ (katà lógon tethén), it is, of course, a symbol, because it can be

represented by a variety of spoken sounds, but it is also a homoíōma, to the extent that

it represents the substance of what it named (Ammon. in Int. 40.18-22).

It is worth noting that in this approach, the representation through spoken sounds is

identified with the symbolic nature: a name can be a ‘likeness’, but its linguistic

realization through spoken sounds is not naturally connected with its substance

(Socrates in Pl. Crat. 431e9-432e2 also says that a name can be composed of various

elements, stoikheîa; Proclus refers to the variety of sounds when representing things: in

Crat. 51.21ff.). The view that the spoken sounds that compose a word are not naturally

connected to its meaning is commonly accepted by the Neoplatonic commentators on

Aristotle, starting with Porphyry: it is not the ‘signified’ (sēmainόmenon) that connects

(sundeî/sunáptei) the syllables of the word with each other (Porph. in Cat. 102.2-8; Simpl.

in Cat. 89.32-90.2, 124.14-19; on the ‘arbitrariness’ of the linguistic sign according to

Neoplatonics, see Chriti 2011).

According to Ammonius, the imposition and use of names is only one of the various

aspects we should take into account when approaching language: Ammonius argues

that language is not ‘by convention’ in an absolute way, observing that Aristotle

himself, when creating new words, followed some ‘guidelines’ of derivation and

composition of the language he used so that his new words could be recognizable

(Ammon. in Int. 37.18-27; see Aristot. Cat. 7a5-7; Eth. Nic. 1108a17-19).

In his effort to reconcile Plato and Aristotle according to the ‘principle of agreement’

(see section 4 above), Ammonius creates new terms for ónoma: homoíōma katà tékhnēn

and súmbolon katà lógon/mḕ askópōs tethén, having assimilated interconnected

philosophical views from Plato, Aristotle and Neoplatonism, but he constructs a more

elaborated theoretical basis concerning language, revealing his awareness that it is a

rather complicated phenomenon which can’t be approached in an absolute way.

5. Conclusion

In general, if we made an attempt to render an overall approach of ancient Greek

philosophical reflection on language, it would not be inappropriate to say that ancient

Greek philosophy on language, beyond specific schools and philosophers, is

multileveled in its entirety. Apart from challenging the relation of linguistic thought to

myth, the views formulated by ancient Greek philosophers from the Pre-Socratics to

the Neoplatonists constructed the basis for grammar and rhetoric during the Middle

Ages and constituted a key frame for the development of contemporary linguistics.

Ademollo, F. 2011. The Cratylus of Plato. A commentary. Cambridge - New York.

Allen, J. “The Stoics on the origin of language and the foundation of etymology.” In: Frede and Inwood 2005:14-35.

Arens, H. 2000. “Sprache und Denken bei Aristoteles”. In: History of the language sciences/Geschichte der Sprachwissenschaften/Histoire des sciences du

11 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

Ancient Philosophers on Language http://brill.stippweb.nl/srw/producten/previewUitOverzicht.asp?id...

langage, eds. S. Auroux, E. F. K. Koerner, H. J. Niederehe, & K. Versteegh, vol. I, 367-374. Berlin - New York.

von Arnim, H. 1903-1924. Stoicorum Veterum Fragmenta, 4 vols. Leipzig.

Asher, R. E. and J. M. Y. Simpson. 1994. The encyclopaedia of language and linguistics, vol. 1. Oxford - New York.

Ax, W. 2000. “Aristoteles (384-322).” In: Lexis und Logos. Studien zur antiken Grammatik und Rhetorik, ed. by W. Ax and F. Grewing, 48-72. Stuttgart.

Bailey, C. [1926] 1980. Epicurus, the extant remains with short critical apparatus, translation, and notes. Oxford.

Barney, R. 2001. Names and nature in Plato’s ‘Cratylus’. London - New York.

Barwick, K. 1957. Probleme der stoischen Sprachlehre und Rhetorik. (Abhandlungen der Sachsischen Akademie der Wissenschaften Philologisch-

historische Klasse 49, 3). Berlin.

Beaucamp, J. 2002. “Le Philosophe et le joueur. La date de la ‘fermeture de l’École d’Athènes’”. In: Mélanges Gulbert Dargon (Travaux et Mémoires 14),

21-35. Paris.

Berg, van den R. M. 2008. Proclus’ commentary on the Cratylus in context: ancient theories of language and naming. (Philosophia Antiqua 112). Leiden -

Boston.

Blank, D. 1996. Ammonius on Aristotle’s “On Interpretation” 1-8. Ithaca, NY.

Blumenthal, H. J. 1993. “Alexandria as a center of Greek philosophy in Later Classical Antiquity”, ICS 18:307-325.

Buxton, R. 2001. From myth to reason? Studies in the development of Greek thought. Oxford.

Chriti, M. 2011. “Neoplatonic commentators on Aristotle: The ‘arbitrariness of the linguistic sign’.” In: Ancient scholarship and Grammar: archetypes,

concepts and contexts, ed. by S. Matthaios, F. Montanari and A. Rengakos, 499-514. (Trends in Classics suppl. Vol. 8). Berlin - New York.

Dalimier, C. 1998. Platon. Cratyle. Paris.

Diels, H. and W. Kranz. 1951-1952. Die fragmente der Vorsokratiker. 2 vols. 6th ed. Berlin.

Egli, U. 1986. Stoic syntax and semantics. In: The history of linguistics in the classical period. (Historiographia Linguistica 13.2-3), ed. by D. J. Taylor, 281-306.

Amsterdam - Philadelphia.

Frede, D. and B. Inwood, eds. 2005. Language and learning: philosophy of language in the Hellenistic Age: Proceedings of the Ninth Symposium Hellenisticum.

Cambridge.

Givόn, T. 2001. Syntax, vol. I. Amsterdam.

Guthrie, W. K. C. 1998 [1971]. The Sophists. Cambridge.

Hülser, K. 1987-1988. Die Fragmente zur Dialektik der Stoiker. Neue Sammlung der Texte mit deutscher Übersetzung und Kommentaren, 4 vols. Stuttgart.

Irwin, T. 1982. “Aristotle’s concept of signification.” In: Language and Logos: studies presented to G. E. L. Owen, ed. by M. Schofield and M. Nussbaum,

241-266. Cambridge.

Karamanolis, G. E. 2006. Plato and Aristotle in agreement? Platonists on Aristotle from Antiochus to Porphyry. Oxford.

Kathryn A. Morgan. 2000. Myth and philosophy from the Presocratics to Plato. Cambridge.

Kirk, G. S. 1954. Heraclitus: the cosmic fragments. Cambridge - New York.

Κοτζιά, Π.. 2007. Περὶ τοῦ μήλου ἢ περὶ τῆς Ἀριστοτέλους τελευτῆς (Peri tou milou é peri tis Aristotelous teleutis, Liber de pomo). Thessaloniki.

Kretzman, N. 1974. “Aristotle on spoken sound singnificant by convention.” In: Ancient logic and its modern interpretations, ed. by J. Corcoran, 3-21.

Dordrecht - Boston.

Lesher, James H. 1992. Xenophanes of Colophon: fragments. Toronto.

Liebermann, W.-L. 1996. “Sprachauffassungen im frühgriechischen Epos und in der griechischen Mythologie.” In: Sprachtheorien der abendländischen

Antike. Geschichte der Sprachtheorie, ed. P. Schmitter, 30-42. Tübingen.

Long, A. A. “Stoic linguistics, Plato’s Cratylus and Augustine’s De dialectica.” In: Frede and Inwood 2005:36-55.

Manetti, G. 1993. Theories of the sign in classical antiquity. Trans. Ch. Richardson. Bloomington.

Manetti, G., ed. 1996. Knowledge through signs. Ancient semiotic theories and practices. (Semiotic and Cognitive Studies II). Bologna.

Manetti, G. “The concept of the sign from ancient to modern semiotics.” In: Manetti 1996:11-40.

Mayhew, R. Prodicus the sophist: texts, translations, and commentary. Oxford - New York.

Modrak, D. K. W. 2001. Aristotle’s theory of language and meaning. Cambridge.

Nussbaum, M. C. 2001. Upheavals of thought. The intelligence of emotions. Cambridge.

Oehler, K. 2006 [1984]. Aristoteles. Kategorien. Berlin.

Ogden, C. K. and I. A. Richards. 1923. The meaning of meaning: a study of the influence of language upon thought and of the science of symbolism. Cambridge.

Schiappa, E. 2003. Protagoras and logos: a study in Greek philosophy and rhetoric. Columbia, South Carolina.

Schmitter, P. 2000. “Sprachbezogene reflexionen im frühen Griechenland.” In: History of the language sciences/Geschichte der

Sprachwissenschaften/Histoire des sciences du langage, ed. by S. Auroux, E. F. K. Koerner, H. J. Niederehe, & K. Versteegh. Vol. I, 345-366. Berlin - New

York.

Sedley, D. “Aristotle’s De Interpretatione and ancient semantics.” In: Manetti 1996:86-108.

Sedley, D. 2003. Plato’s Cratylus. Cambridge.

Sedley, D. 2006. The midwife of Platonism: text and subtext in Plato’s Theaetetus. Oxford.

Sluiter, I. 1990. Ancient grammar in context: contributions to the study of ancient linguistic thought. Amsterdam.

Sorabji, R. 1990. Aristotle transformed. London.

Sorabji, R. 2005. The philosophy of the commentators, 200-600 AD: a sourcebook. Ithaca, NY.

Struck, P. T. 2004. Birth of the symbol. Princeton - Oxford.

Verbeke, G. “Meaning and role of the expressible (λεκτόν) in Stoic logic”. In: Manetti 1996:133-153.

Weidemann, H. 1991. “Gründzüge der aristotelischen Sprachtheorie”. In: Sprachtheorien der abendlδndischen Antike, ed. by P. Schmitter,170-192.

Tübingen.

Westering, L. G., J. Trouillard and A. Ph. Segonds. [1990] 2003. Prolégomènes à la philosophie de Platon. Paris.

Pre-Socratics, Heraclitus, Parmenides, Sophists, Protagoras, Plato's Cratylus, Aristotle's On

Interpretation, Democritus, origins of language, semiotic triangles, Stoics

PARASKEVI KOTZIA ✝

MARIA CHRITI

Attachments

pdf of original

12 van 12 5-11-2013 11:37

You might also like

- Classifying Christians: Ethnography, Heresiology, and the Limits of Knowledge in Late AntiquityFrom EverandClassifying Christians: Ethnography, Heresiology, and the Limits of Knowledge in Late AntiquityNo ratings yet

- The Belief in Intuition: Individuality and Authority in Henri Bergson and Max SchelerFrom EverandThe Belief in Intuition: Individuality and Authority in Henri Bergson and Max SchelerNo ratings yet

- Raoul Mortley What Is Negative Theology The Western OriginDocument8 pagesRaoul Mortley What Is Negative Theology The Western Originze_n6574No ratings yet

- Gnostic Mindset in Cultural TransitionDocument11 pagesGnostic Mindset in Cultural TransitionMarco LucidiNo ratings yet

- Philo's de Vita Contemplativa As A Philosopher's Dream - Engberg-PedersenDocument25 pagesPhilo's de Vita Contemplativa As A Philosopher's Dream - Engberg-PedersenGabriele CornelliNo ratings yet

- Re-Evaluating E. R. Dodds Platonism PDFDocument44 pagesRe-Evaluating E. R. Dodds Platonism PDFVeronica JohnsonNo ratings yet

- Elohim - WikipediaDocument8 pagesElohim - WikipediaAlejandroNo ratings yet

- Religious Syncretism in Mediterranean He PDFDocument10 pagesReligious Syncretism in Mediterranean He PDFJoanir Fernando RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Maximus of Tyre, What Divinity Is According To PlatoDocument6 pagesMaximus of Tyre, What Divinity Is According To PlatonatzucowNo ratings yet

- The Arians of AlexandriaDocument13 pagesThe Arians of AlexandriaPandexaNo ratings yet

- Heraclitus’ Holistic Insights on the LogosDocument12 pagesHeraclitus’ Holistic Insights on the LogosUri Ben-Ya'acovNo ratings yet

- John Heiser-The Great Reunion of 1913Document44 pagesJohn Heiser-The Great Reunion of 1913Andrew SmallNo ratings yet

- Dylan Burns - Apophatic Strategies in Allogenes (NHC XI, 3) PDFDocument19 pagesDylan Burns - Apophatic Strategies in Allogenes (NHC XI, 3) PDFManticora PretiosaNo ratings yet

- The Shepherd of Thrice-Great Hermes: Book 1 1 at The Time When MyDocument13 pagesThe Shepherd of Thrice-Great Hermes: Book 1 1 at The Time When MyMindSpaceApocalypse100% (1)

- Unwritten DoctrinesDocument1 pageUnwritten Doctrinesaguirrefelipe100% (1)

- Alexandrian Logos Systasis 29 4Document15 pagesAlexandrian Logos Systasis 29 4Njono SlametNo ratings yet

- In Defence of The LogosDocument52 pagesIn Defence of The LogosRathamanthys MadytinosNo ratings yet

- Negative Theology in Contemporary InterpretationDocument22 pagesNegative Theology in Contemporary Interpretationjohn kayNo ratings yet

- Dillon J., Intellect and The One in Porphyry's Sententiae, IJPT IV, 2010Document9 pagesDillon J., Intellect and The One in Porphyry's Sententiae, IJPT IV, 2010Strong&PatientNo ratings yet

- Eriugena: Champion of Western OrthodoxyDocument14 pagesEriugena: Champion of Western OrthodoxyΠΤΟΛΕΜΑΙΟΣ ΗΡΑΚΛΕΙΔΗΣNo ratings yet

- The Manichaean Challenge To Egyptian ChristianityDocument14 pagesThe Manichaean Challenge To Egyptian ChristianityMonachus Ignotus100% (1)

- Guy G Stroumsa Madness and DivinizationDocument17 pagesGuy G Stroumsa Madness and DivinizationSofia IvanoffNo ratings yet

- Convergence of Religions Kenneth OldmeadowDocument11 pagesConvergence of Religions Kenneth Oldmeadow《 Imperial》100% (1)

- Aristotle On Interpretation - Commentary (Aquinas, St. Thomas)Document225 pagesAristotle On Interpretation - Commentary (Aquinas, St. Thomas)Deirlan JadsonNo ratings yet

- The Logos Concept A Critical Monograph On John 1: 1 Abridged by The AuthorDocument10 pagesThe Logos Concept A Critical Monograph On John 1: 1 Abridged by The AuthorDavidNo ratings yet

- Mcginn2014 Exegesis As Metaphysics - Eriugena and Eckhart On Reading Genesis 1-3Document38 pagesMcginn2014 Exegesis As Metaphysics - Eriugena and Eckhart On Reading Genesis 1-3Roberti Grossetestis LectorNo ratings yet

- Aristotle and His TraditionDocument13 pagesAristotle and His TraditioncyganNo ratings yet

- OrigenTrinitarian Autorship Og BibleDocument9 pagesOrigenTrinitarian Autorship Og Bible123KalimeroNo ratings yet

- Reumann - Oikonomia, Studia Patristica 3, 1961Document10 pagesReumann - Oikonomia, Studia Patristica 3, 1961123KalimeroNo ratings yet

- Apollonius of Tyana - MalpasDocument99 pagesApollonius of Tyana - MalpasMark R. JaquaNo ratings yet

- 351 - en - A Note On To Par Hemas and To Eph Hemin in ChrysippusDocument5 pages351 - en - A Note On To Par Hemas and To Eph Hemin in ChrysippusumityilmazNo ratings yet

- The Emergence of Gnostic-Manichaean Christianity As A Case of Religious Identity in The MakingDocument8 pagesThe Emergence of Gnostic-Manichaean Christianity As A Case of Religious Identity in The Makingnarayana assoNo ratings yet

- Neoplatonism: The Great Goddess. San Francisco, 1979. A Description of TheDocument3 pagesNeoplatonism: The Great Goddess. San Francisco, 1979. A Description of TheAnonymous pjwxHzNo ratings yet

- Bibliographical Bulletin For Byzantine Philosophy 2010 2012Document37 pagesBibliographical Bulletin For Byzantine Philosophy 2010 2012kyomarikoNo ratings yet

- S. Cooper The Platonist Christ. of M. VictorinusDocument24 pagesS. Cooper The Platonist Christ. of M. VictorinusAnonymous OvTUPLm100% (1)

- Pythagoras Northern Connections Zalmoxis Abaris AristeasDocument17 pagesPythagoras Northern Connections Zalmoxis Abaris AristeasЛеонид ЖмудьNo ratings yet

- Plato's Critique of the Golden Age TraditionDocument17 pagesPlato's Critique of the Golden Age Traditioncecilia-mcdNo ratings yet

- Francesco PatriziDocument14 pagesFrancesco PatriziIvana MajksnerNo ratings yet

- Adolph Von Menzel - Historical and Literary Studies Pagan Jewish and Christian Cd6 Id471145024 Size80Document19 pagesAdolph Von Menzel - Historical and Literary Studies Pagan Jewish and Christian Cd6 Id471145024 Size80HotSpireNo ratings yet

- 1-17. The Logos in John's PrologueDocument16 pages1-17. The Logos in John's PrologueDaryl BadajosNo ratings yet

- Dialectic of LogosDocument32 pagesDialectic of LogosDavidNo ratings yet

- Epicurus Theological InnatismDocument14 pagesEpicurus Theological InnatismRodrigo Córdova ANo ratings yet

- On Not Being Silent in The Darkness: Adorno's Singular ApophaticismDocument33 pagesOn Not Being Silent in The Darkness: Adorno's Singular ApophaticismcouscousnowNo ratings yet

- Patristic Views On Hell-Part 1: Graham KeithDocument16 pagesPatristic Views On Hell-Part 1: Graham KeithНенадЗекавицаNo ratings yet

- Religion and The Everyday Life of Manichaeans in Kellis: Mattias Brand - 978-90-04-51029-6 Via Free AccessDocument425 pagesReligion and The Everyday Life of Manichaeans in Kellis: Mattias Brand - 978-90-04-51029-6 Via Free Accessvirgil strohmeyerNo ratings yet

- Moran - Pantheism in Eriugena and Cusa (1990)Document20 pagesMoran - Pantheism in Eriugena and Cusa (1990)known_unsoldier100% (1)

- Philo of AlexandriaDocument7 pagesPhilo of AlexandriaBryan Alexis Tan GayonNo ratings yet

- American Academy of ReligionDocument25 pagesAmerican Academy of ReligionAnglopezNo ratings yet

- Augustine and Manichaean Christianity ADocument15 pagesAugustine and Manichaean Christianity ANURETTİN ÖZTÜRKNo ratings yet

- Plato S Influence On Gerogios Gemistos PDocument20 pagesPlato S Influence On Gerogios Gemistos PtreebeardsixteensNo ratings yet

- Feminine Power in Proclus Commentary OnDocument24 pagesFeminine Power in Proclus Commentary OnVikram RamsoondurNo ratings yet

- Eriugena IdealismDocument30 pagesEriugena IdealismLaura SmitNo ratings yet

- Epicurus - All Sensations Are TrueDocument15 pagesEpicurus - All Sensations Are TrueLeandro FreitasNo ratings yet

- The Mixed Life of Platos Philebus in Psellos The Contemplation in Saint Maximus The ConfessorDocument11 pagesThe Mixed Life of Platos Philebus in Psellos The Contemplation in Saint Maximus The ConfessorBogdan VladutNo ratings yet

- Burkhard Mojsisch - Meister Eckhart - Analogy, Univocity and Unity (2001, B.R. Grüner Pub. Co.)Document236 pagesBurkhard Mojsisch - Meister Eckhart - Analogy, Univocity and Unity (2001, B.R. Grüner Pub. Co.)jffweber100% (1)

- Aquinas AbstractionDocument13 pagesAquinas AbstractionDonpedro Ani100% (2)

- Neoplatonism and Maximus The Confessor oDocument10 pagesNeoplatonism and Maximus The Confessor oNikNo ratings yet

- O. THE ACTS AND FACULTIES OF THE SENSITIVE SOULDocument11 pagesO. THE ACTS AND FACULTIES OF THE SENSITIVE SOULPablo NavarreteNo ratings yet

- Cook - 4Q246 Mesiah-Son of God PDFDocument24 pagesCook - 4Q246 Mesiah-Son of God PDFAndy BG 67No ratings yet

- Who Really Wrote The GospelsDocument16 pagesWho Really Wrote The GospelsJan Paul Salud LugtuNo ratings yet

- MARCIANO (Images and Experience. at The Roots of Parmenides' Aletheia) (PY 2008) PDFDocument28 pagesMARCIANO (Images and Experience. at The Roots of Parmenides' Aletheia) (PY 2008) PDFmalena_arce_2No ratings yet

- Incantatory Practices Between Oral 2. Ity and WritingDocument23 pagesIncantatory Practices Between Oral 2. Ity and WritingJo GaduNo ratings yet

- Plato's Philosophy of Language: Paolo CrivelliDocument25 pagesPlato's Philosophy of Language: Paolo CrivelliJo GaduNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 187.232.126.115 On Tue, 04 Aug 2020 16:15:32 UTCDocument8 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 187.232.126.115 On Tue, 04 Aug 2020 16:15:32 UTCJo GaduNo ratings yet

- Incantatory Practices Between Oral 2. Ity and WritingDocument23 pagesIncantatory Practices Between Oral 2. Ity and WritingJo GaduNo ratings yet

- The Neoplatonic Commentators of Aristot PDFDocument1 pageThe Neoplatonic Commentators of Aristot PDFJo GaduNo ratings yet

- Ammonius Commentary On Aristotle S de I PDFDocument1 pageAmmonius Commentary On Aristotle S de I PDFJo GaduNo ratings yet

- 10 1017@9781139235747 011Document8 pages10 1017@9781139235747 011Jo GaduNo ratings yet

- Parmenides Principle PDFDocument13 pagesParmenides Principle PDFJo GaduNo ratings yet

- And in Parmenides PDFDocument44 pagesAnd in Parmenides PDFJo GaduNo ratings yet

- The Body Politic Atius On Alcmaeon On Isonomia and MonarchiaDocument19 pagesThe Body Politic Atius On Alcmaeon On Isonomia and MonarchiaJo GaduNo ratings yet

- Kou Lou Ment As 2014Document22 pagesKou Lou Ment As 2014Jo GaduNo ratings yet

- Meaning, Thought, & RealityDocument10 pagesMeaning, Thought, & RealitySorayaHermawan100% (1)

- Improve Students' English Vocabulary with Dora CartoonsDocument64 pagesImprove Students' English Vocabulary with Dora CartoonsMuhammad Al-fatih100% (1)

- Discourse Analysis and GrammarDocument50 pagesDiscourse Analysis and GrammarJean Valerie SumayaNo ratings yet

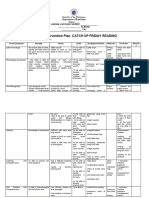

- Reading Intervention Plan CATCH UP FRIDAY READINGDocument3 pagesReading Intervention Plan CATCH UP FRIDAY READINGErjohn Oca100% (1)

- DLL Grade3 1stquarter WEEK5Document10 pagesDLL Grade3 1stquarter WEEK5MARICAR PALMONESNo ratings yet

- FCE - Exam: B2 First For SchoolsDocument26 pagesFCE - Exam: B2 First For SchoolsNele Loubele PrivateNo ratings yet

- Chapter 6: Assessing Listening (Brown)Document3 pagesChapter 6: Assessing Listening (Brown)Arif RahmanulhakimNo ratings yet

- 712385Document243 pages712385Валентина МанєтоваNo ratings yet

- Features of Academic Spoken EnglishDocument4 pagesFeatures of Academic Spoken EnglishWahyu AdamNo ratings yet

- Marvel EssayDocument3 pagesMarvel Essayapi-349043985No ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence ProjectDocument20 pagesArtificial Intelligence ProjectMonika MathurNo ratings yet

- English: Quarter 4 - Module 3: Week 3: Identify Prepositions in SentencesDocument37 pagesEnglish: Quarter 4 - Module 3: Week 3: Identify Prepositions in SentencesGracey Dapon100% (1)

- Lesson Plan - Synonyms and AntonymsDocument3 pagesLesson Plan - Synonyms and Antonymsapi-295139406100% (8)

- 2023年1-4月模考盒子David考官雅思口语素材 Part 1Document27 pages2023年1-4月模考盒子David考官雅思口语素材 Part 1Limin DingNo ratings yet

- Morpheme PDFDocument2 pagesMorpheme PDFDavid100% (3)

- History of English Grammars and Approaches to Parts of SpeechDocument46 pagesHistory of English Grammars and Approaches to Parts of SpeechkanoebvNo ratings yet

- Remedial English InstructionDocument11 pagesRemedial English InstructionGilmar Papa De Castro100% (1)

- The Word MeaningDocument81 pagesThe Word MeaningThạch Hoàng SơnNo ratings yet

- Language and CommunityDocument12 pagesLanguage and CommunitySammy WizzNo ratings yet

- IC AnalysisDocument16 pagesIC AnalysisSibghaNo ratings yet

- A Game of Pinoy HenyoDocument6 pagesA Game of Pinoy HenyoIlac Capangpangan100% (1)

- Mindmap SemanticsDocument1 pageMindmap SemanticsJustoNo ratings yet

- ENG101 Handouts 1 45Document295 pagesENG101 Handouts 1 45Adnan Gulshan50% (2)

- Is British English Being Swamped by AmericanismsDocument70 pagesIs British English Being Swamped by AmericanismsNick WalkerNo ratings yet

- A Hypothetical Situation:: The Language of MathematicsDocument9 pagesA Hypothetical Situation:: The Language of MathematicsYngKye YT100% (1)

- Semantics. Causes of Semantic ChangeDocument3 pagesSemantics. Causes of Semantic ChangeMarina TanovićNo ratings yet

- What Is Language AcquisitionDocument7 pagesWhat Is Language AcquisitionMuhammad AbidNo ratings yet

- Language Planning in PunjabDocument7 pagesLanguage Planning in Punjabapi-3756098No ratings yet

- Father's Role in FamilyDocument17 pagesFather's Role in FamilyElner Dale Jann GarbidaNo ratings yet

- All About Me: Introducing Myself in EnglishDocument19 pagesAll About Me: Introducing Myself in Englishlilith lsvNo ratings yet