Professional Documents

Culture Documents

012 - 1965 - Law of Evidence PDF

Uploaded by

shrinivas legalOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

012 - 1965 - Law of Evidence PDF

Uploaded by

shrinivas legalCopyright:

Available Formats

LAW OF EVIDENCE

Krishna Bahadur*

T H E NUMBER O F cases on the law of evidence is as usual legion. T h e

courts have, by a n d large, applied only t h e established principles of

law while deciding upon the admissibility of the facts in a particular

case. Every case, however, presents a unique set of facts a n d it is not

surprising t h a t the principles of law in t h e process of their application by

the courts are at times modified and, m a y be, in some cases mutiliated.

T h e discovery of new principles from the plethora of cases is possible only

if a detailed analysis is m a d e of the fact situations in the precedent cases

side by side with the situations in the instant cases. This survey ende

avours to study the judicial trends in the techniques of fact ascertainment

by analysing the cases arising out of the interpretation of some of t h e im

portant provisions of the I n d i a n Evidence Act, 1872.

II. RELEVANCY OF FACTS AND ADMISSIBILITY OF EVIDENCE

A. Facts in Issue and Relevant Facts

Evidence may b e given of facts in issue a n d relevant facts only. 1

Only such facts are relevant as are specifically described a n d illustrated

in the I n d i a n Evidence Act. 2 A court, therefore, cannot take a fact as

proved without considering the matters before it within the requisite

degree of probability 3 . W h e r e , for example, wagons were looted a n d

consignments therein were lost as a result of communal disturbances, the

Supreme Court in Shiv Nath v. Union of India* did not take as proved the

fact that the applicant's consignments were also lost through the same

circumstances. T h e facts t h a t have a bearing o n t h e evidence or non

existence of a fact in issue may vary from case to case. 5

(1) Res Gestae

For the application of the doctrine of res gestae, the fact in issue must

b e proved. I n Kashmira Singh v. State,* neither the F . I . R . w a s proved nor

♦M.A., LL.M; Lecturer, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi.

1. Section 3, Indian Evidence Act.

2. Section 11, id.

3. Daitari Das v. Kulamani., AJ.R. 1965 Orissa 21; D.K. Jain v. State, AJ.R.

1965 All. 525.

4. AJ.R. 1965 S.C. 1966.

5. Indian Airlines v. Madhuri Chowdhuri, AJ.R. 1965 Cal. 252.

6. AJ.R. 1965 J.& K. 37.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

192 ANNUAL SURVEY OF INDIAN LAW

the informant was produced before the court. The only witness was a

by-stander who had neither seen with his own eyes nor heard with his

own ears that the accused had used any indecent language against the

complainant or insulted her. Obviously, the fact in issue was not proved

but the Court held the evidence of the by-stander relevant as forming

part of the same transaction. Similarly, in Indian Airlines v. Madhuri

Chowdhuri,7 the report of the Enquiry Commission relating to the causes

of the aircraft crash was held relevant as it spoke of the occasion, cause

or effect of the fact in issue, that is, the aircraft crash. It may, however,

be submitted that even on the assumption that relevancy is always a

question of judicial discretion to be determined according to the issue to

be tried, the evidence of the by-stander and the report of the Enquiry

Commission do not form part of the same transactions. No doubt, it

is largely in the judicial discretion to admit an evidence as res gestae but

it must have a close proximity with the fact in issue which, in these

cases, it was difficult to locate.

The first part of section 8 of the Indian Evidence Act lays down

that fact which constitutes a motive or preparation of a fact in issue is

relevant. The latter part of this section deals with the relevancy of pre

vious and subsequent conduct. This section, therefore, presupposes the

existence of fact in issue. The Bombay High Court in State v. Hiramans

accordingly held that the statement of a ravished minor girl, aged four,

explaining the incident and naming the accused to her mother after the

commission of the offence under section 376, Indian Penal Code, on her

by the accused, was relevant as amounting to subsequent conduct. Sec

tion 9 makes relevant only those facts which are necessary to explain or

to introduce relevant facts in issue. Such facts may also be termed as

"link evidence." Since to attract the doctrine of res gestae, the existence

of fact in issue is presupposed, it is necessary that the identity of the

fact "to be linked with" and the identity of the fact "to be linked to" must

both be established. For example, in the absence of the identity of a

recovered gun having been established, it is difficult to see how the fact

of recovery could form a link to it. The application of the doctrine in

State v. Dhanwan,9 where the identity of the recovered article was not

proved, would not be a sound principle of law,

(2) Conspiracy

The agreement necessary for the offence of conspiracy can be proved

either by direct evidence or be inferred from acts and conduct of

7. Supra note 5.

8. AJ.R. 1965 Bom. 154.

9. AJ.R. 1965 All 260. Mathur, J., observed that "We are of the opinion that the

evidence of recovery can be accepted even though the recovered article has not been

sealed soon after the recovery and no link evidence was adduced during trial, provid-

(Continued on next page)

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

LAW OF EVIDENCE 193

parties. 1 0 T h e court has first to be satisfied that reasonable ground exists

to believe that two or more persons have conspired together to commit a n

offence or a n actionable wrong. T h e r e should, therefore, be prima facie

evidence t h a t a person was party to the conspiracy a n d that his a c t was

in reference to the common intention of all 1 1 a n d related to the period

after such intention was entertained by any one of them. It m a y b e

observed that the first p a r t of section 10 is m a n d a t o r y in the sense that

unless the court has reasonable ground to believe of the existence cf

conspiracy, the latter p a r t of the section is inoperative. 1 2 A peculiar

situation in this respect may sometimes arise where u p to a certain stage

of evidence, the court has reasonable ground to believe t h a t a conspiracy

existed but later on, it comes to the conclusion t h a t no grounds exist

further for the same. Dealing with a situation like this, the Calcutta

High Court in Samunder Singh v. State13 said : " A trial judge may a d m i t

evidence under section 10 of the Evidence Act where h e has a reasonable

ground to believe as is postulated, yet he m a y reject it if at a later stage of

the trial that gound of belief is displaced by further evidence. It is not

the true view that in a conspiracy charge, evidence once admitted remains

admissible evidence whatever new aspect the case may assume w h e t h e r

in the original or in the appellate court." 1 4

B. Statements Made Under Special Circumstances

(1) Entries in Books of Accounts

T h e evidentiary value of the entries m a d e in a book of accounts was

determined by the courts in a n u m b e r of cases. T h e Orissa H i g h Court

in Haribux Gauri Shanker Firm v. Subhakaran Tulsirarn^ emphasised that

what is relevant is the entry regularly m a d e in the course cf business.

It is, however, submitted t h a t the words "regularly k e p t " in section 34

ed that the court is satisfied on consideration of the material on record and the circums

tances of the case that the article produced before the court is the same which had

been recovered from the possession of the accused." Id. at 263.

10. Bhagwan Swarup v. State of Maharashtra, AJ.R. 1965 S.C. 682.

11. Samunder Singh v. State, AJ.R. 1965 Cal. 598.

12. See the following observations of Subba Rao, J., in Bhagwan Swarup v.

State of Maharashtra, supra npte 10, at 687:

Another important limitation implicit in the language is indicated by the expre

ssed scope of its relevancy. Anything so said, done or written is a relevant fact

only as against each of the persons believed to be so conspiring as well for the

purpose of proving the existence of the conspiracy as for the purpose of show

ing that any such person was a party to it. It can only be used for the purpose

of proving the existence of the conspiracy or that the other person was a

party to it. It cannot be used in favour of the other party or for the purpose of

showing that such a person was not a party to the conspiracy.

13. Supra note 11.

14. Id at 606.

15. A.LR. 1965 Orissa 211.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

194 ANNUAL SURVEY OF INDIAN LAW

govern a n d qualify " e n t r i e s " as well as "books of accounts." It is not

clear w h e t h e r the Court while determining the relevancy of entries im

pliedly also included the relevancy of the books containing such entries.

T h e cases under review did not lay down a sound law as regards

the latter p a r t of section w h i c h determines the evidenciary value of

such entries a n d lays down that they, by themselves, would not be suffi

cient evidence. It would be unnecessary to r e a d in this part of the sec

tion a m a n d a t o r y requirement towards corroboration of such entries as

general corroborative test to such entries would in any case apply under

the general principles of the law of corroboration. It seems that the

A n d h r a Pradesh High Court in Aswathanarayanaiah v. Sanjeeviah1® a n d

the Assam H i g h Court in H. Motor Works v. Harnath Barua17 did not

consider this aspect while upholding the importance of the latter part.

I n fact, the latter p a r t of section 34 almost abrogates the evidenciary

force of the earlier p a r t of the section by taking away whatever the earlier

p a r t gives. I t seems that in view of the general law of corroboration,

a specific requirement in this regard as contained in the latter part of the

section is unnecessary a n d it is, therefore, suggested that section 34 may

r e a d : "Entries in books of account, regularly kept in the course of

business, a n d relevant whenever they refer to a m a t t e r into which the

court has to e n q u i r e . " Such a n a m e n d m e n t would not make any diffe

rence in the principles a n d scope of section 34 as evidence of such entries

would, like other evidence, be still open to corroboration, veracity and

satisfaction of the courts.

(2) Public Record

T h e term "public r e c o r d " as used in section 35 has been one of vary

ing connotations. T h e C a l c u t t a H i g h Court in Indian Airlines v. Madhuri

Chowdhurixs held t h a t the report of the statutory Enquiry Commission

set u p under the Aircrafts Act, 1934,, was not relevant. However, the

Supreme Court in Periaswami v. Sunderesa Ayyar1Q laid down that the

entry in the " I n a m register" m a d e by the I n a m d a r was relevant. These

cases do not point out as to which record amounts to a public record and

what workable tests can be laid down to ascertain whether a record is

a public record. T o resolve such uncertainties, the proper test, it may

be suggested, would be to hold that a public record is one which is kept

or issued under the authority of law. I n this sense, the report of a statutory

enquiry commission would be a public record. 2 0

16. AJ.R. 1965 A.P. 33.

17. AJ.R. 1965 Assam 10.

18. Supra note 5.

19. AJ.R. 1965 S.C. 516.

20. Under section 73, Indian Evidence Act, the following are public documents:—

(1) Documents forming the acts or records of the acts—

(i) of the sovereign authority,

{Continued on next page)

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

LAW OF EVIDENCE 195

In Brij Mohan v. Priya Brat21 the issue was whether an entry of

birth made in the official register, maintained by an illiterate chowkidar,

by another person at the request of the chowkidar is relevant. The

Supreme Court observed that the words "made by a public servant" mean

made by a public servant himself. It may be pointed out here that,

since the latter part of section 35 reads "made by a public servant in the

discharge of his official duties" the words "in the discharge of his official

duties" are inended to qualify *'public servant" and therefore an entry

so made whether by public servant himself or at his request by someone

else would be relevant. In this case, there was no evidence to show that

the entry was made not at the request of the chowkidar in the discharge

of his official duties and not to his satisfaction and belief to its being correc

tly made. The Supreme Court on the basis of the "doctrine of probabi

lity" rejected this evidence saying that "when a public servant makes the

entry himself in the discharge of his official duties, the probability of its

being truly and correctly recorded is high. That probability is reduced

to a minimum when the public servant himself is ^illiterate and has to

depend on somebody else to'make the entry." 22 The true import of sec

tion 35 is that the entries should have been made "in the discharge of

official duties." Hence, once the fact that the entries were made by a

public servant in the discharge of official duties is proved, the entries

should be deemed to be properly and correctly made and should accor

dingly be relevant. It may, however, also be said that the intention of the

legislature at the time when the Act was passed in 1872 and when village

chowkidars, who used to be mostly illiterate, were entrusted with the duty

of recording births and deaths in official registers could not have been

otherwise.

C. Opinions of Experts

The courts have not readily accepted the expert opinion tendered

before them in various cases. In Mahendra v. Sushila^ the Supreme

Court held that the court must decide a question over which the opi

nions of two experts differ. Where "best evidence" is available, the

evidence of experts should be excluded. Similarly, the Rajasthan High

Court in State v. Babulal^ observed that the evidence of two doctors in

fixing the age of a girl between 16 and 19 years was based on mere opinion

which speaks of probabilities and therefore should be rejected as against

(ii) of official bodies and tribunals, and

(iii) of public officers, legislative, judicial and executive of any part of India

or of the Commonwealth or of a foreign country;

(2) public records kept in any State of private documents.

21. A.LR. 1965 S.C. 282.

22. Id. at 286.

23. A.I.R. 1965 S.C. 364.

24. AJ,R. 1965 Raj. 90.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

196 ANNUAL SURVEY OF INDIAN LAW

the definite assertion of the father of the girl. The Supreme Court in

Ranjit Udeshi v. State of Maharashtra2^ went to the extent of saying that no

question should entirely depend on oral evidence of writers and art critics.

The identity of handwriting can be proved either by an expert or

by a person acquainted with such handwriting. Under section 73,

the court itself can also compare the two handwritings of a person.

But as laid down by the Patna High Court in Bhupendra Narain v. Ek

Narain Lai,26 direct evidence to prove handwriting must be preferred

to expert evidence on the same point. Accordingly, evidence of the per

son acquainted in the ordinary course of nature with the handwriting of

another person is a direct evidence and, unless it is manifestly in contra

diction to expert evidence, it must be admitted. 27 The Rajasthan High

Court in Jiwa Ram v. State28 analysed the principles regarding the forming

of opinion about the relationship and said that, firstly, there must be a

case where the court has to form an opinion as to the relationship of one

person to another, and, secondly, the person whose opinion is relevant

must be a person who, as a member of the family or otherwise, has special

means of knowledge on the particular subject of relationship. In other

words, the person must fulfil the conditions laid down in the later part

of the section. The scope of the proviso to section 50 was thus explained

in Phankari v. State29: "the marriage of the husband or the wife or the

admission made by the parties or any presumption...will not be suffi

cient to prove the existence of marriage contemplated by section 494." 30

These cases reveal that the courts have been careful and reluctant in

admitting the opinions of experts and third persons and were conscious

of the fact that experts often form their opinions impulsively and at times

with unconscious leanings.

D. Confessions to Persons in Authority

The judgment of the Bombay High Court in Laxman Padma v. Statezl

provides an apt summing up of the scope of section 24 of the Evidence

Act. The Court observed that in order to attract the application of the

section, the following essentials must be present: (i) the confession has

25. A.I.R: 1965 S.C. 881.

26. A.I.R. 1965 Pat. 332.

27. Inder Narayan v. Rup Narain, A.I.R. 1965 M.P. 107, 111:

Where the opinion-evidence excludes the happening either as impossible or as

so highly improbable as to be a practical impossibility, then, of course, one

should hesitate to accept even the direct evidence for the simple reason that

miracles do not happen. Certainly, where the direct evidence itself is doubtful

and is rendered improbable by the expert evidence, then also one should hesitate

to accept it.

28. A.LR. 1965 Raj. 32.

29. A.LR. 1965 J. & K. 105.

30. Id. at 110.

31. A.LR. 1966 Bom. 195.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

LAW OF EVIDENCE 19 7

been made to a person in authority; (ii) it must appear to t h e court

that confession has been procured by a n inducement, threat or promise;

(iii) such inducement, threat or promise must have a reference to the

charge in question a n d that by making such a confession, the accused,

in the opinion of the court, believed that h e would gain any advantage

or avoid any evil of a temporal n a t u r e in reference to the proceedings

against him.

W h o is a person in authority is a very controversial determinative

factor. T h e t e r m has not been defined in the Act a n d hence, to inter

pret it, English cases have often been relied upon. T h e term is generally

accepted to m e a n a person w h o has the power to arrest, detain, examine

or prosecute the accused a n d w h o has also the power to carry out the

inducement, threat or promise. 3 2 T h e Gujarat H i g h Court in Punja

Mava v. State*3 clarified t h e construction of t h e t e r m *'inducement"

and said that where t h e police p a t e l was one amongst t h e people offering

inducement to the person accused a n d the police patel not protesting

a n d not leaving the party, the inducement could be said to have p r e -

ceeded from him as well and, in the circumstances, the mere presence cf

the police patel was sufficient to give the accused a reasonable ground

to believe t h a t by making the confession, h e would be saved by all

the persons concerned including t h e police p a t e l .

W h a t constitutes a " t h r e a t " is another determinative factor. I n

the Laxman Padma case, the Court was called upon to decide as to w h a t

conduct of the person in authority would constitute "threat. 5 * T h e

facts of the case were t h a t a customs officer acting under section 171-A

of the Sea Customs Act h a d summoned t h e accused in a n enquiry con

nected with the suspected smuggling of goods by t h e accused, T h e

points raised during the proceedings were, firstly, w h e t h e r a customs

officer is a person in authority; secondly, w h e t h e r the compelling pro

visions of a statute, for example, section 171-A of Sea Customs A c t ,

amount to " t h r e a t " ; a n d lastly, w h e t h e r the customs officer, in explain

ing the provisions of section 171-A of the Sea Customs Act to a person

summoned t h a t h e is b o u n d to give his statement a n d to state t h e t r u t h ,

gives a " t h r e a t " to the person so summoned. The^Court a c c e p t e d t h e

view that a customs officer is a person in authority. I n respect of the

second question, T a m b e , J . , h e l d that " i n the language of section 24,

it is n:>t every threat that falls within mischief b u t it must be a threat

proceeding from a person in a u t h o r i t y , " 3 4 T h e j u d g m e n t proceeds to

state:

Now what has happened here is that the ofScers who recorded the state

ments have only explained the punitive provisions of law contained in section

171-A of the Act. The compulsion therein, even though it may amount to

32. Ibrahim v. R, (1914) A.C. 599.

33. A.I.R. 1965 Guj. 5.

34. Supra note 31, at 209.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

198 ANNUAL SURVEY OF INDIAN LAW

a threat, emanates not from the officer who was recording the statement but

emanates from the provision of law. What is contemplated in section 24

is that the threat must emanate from the person in authority.35

And a t yet another p l a c e , t h e same Court observed: " I t is not in

dispute t h a t the officers w h o have recorded confessions are persons in

authority within the meaning of Section 24. " 3 0 T h u s it is clear that

t h e customs officer has b e e n a c c e p t e d to be a person in authority. T h a t

the compelling provisions of section 171-A of the Sea Customs Act

amount to " t h r e a t " has also been accepted. But the Court rejected

the plea t h a t the threat emanates from the customs officer. O n this

point, it is submitted, that the word " a n y " used before "inducement,

threat or p r o m i s e " is of a very wide connotation. I t includes threats

m a d e through direct communication as well as by way of explanations

provided, of course, that it emanates from a person in authority like

the customs officer. By narrowing down the construction of the term

" t h r e a t " by technicalities, not a very wholesome principle of law was

laid down in this case.

During the period under survey, it is noteworthy that the courts

acted as keen a n d vigilant defenders of the accused against confessional

statements. T h u s t h e Court in the Laxman Padma case 3 7 further ob

served that the term police officer is not confined only to such officers

w h o are appointed under the I n d i a n Police Act but also includes

officers who exercise the same powers as t h a t of a police officer of a police

station in respect of investigation of certain offences. T h e mere fact

t h a t such officers are also enjoined with duties other t h a n investigating

certain offences would not be a good reason for holding that they

are not police officers provided the powers exercised by t h e m are the

powers of investigation under the Criminal Procedure Code a n d which

are exercisable by a police officer incharge of the police T h a n a .

Similarly, the term " m a d e to police officer" implies that there must

be some direct or indirect nexus or connection between the person

making the statement a n d the police officer. I n Punja Mava v. State38

the Gujarat High Court said that the police custody is deemed to extend

even w h e n the accused submitted himself to the interrogation a n d made

statements about t h e discovery of facts in issue w h e n h e could not,

therefore, be said to be a free m a n . Analysing the scope of section 27 39

in relation to sections 25 a n d 26, the Court further s a i d :

If the statement to any such police officer is hit under sec. 25 or 26 as tain

ted evidence, the principle underlying sec. 27 viz. that the evidence relating

to confessional or other statements made by a person while a person is in

35. Ibid.

36. Id. at 208.

37. Supra note 31.

38. Supra note 33.

39. Section 27 is, in fact, nothing more than a proviso to sections 25 and 26.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

LAW OF EVIDENCE 199

the custody of the police is tainted and, therefore, inadmissible, but if the

truth of the information given by him is assured by the discovery of a fact, it

may be presumed to be untainted, must apply to all such statements.40

Not too clear a picture, through the judgments, has been held out

of retracted confessions as the courts stressed on the need of its corrobo

ration. T h e q u a n t u m of corroboration should depend u p o n a n d be

determined according to the material facts. T h e Gujarat H i g h Court,

it seems, relied too m u c h on the theory of "court conscience" by saying

that the extent of corroboration of confessional statements should be

such as satisfies the conscience of the court depending upon the circums

tances a n d the facts u n d e r which the confession was m a d e a n d was r e

tracted. It may, however, be pointed out here that the Supreme Court

in Pyarelal v. State of Rajasthan*1 h a d clearly laid down t h a t although

corroboration of retracted confession is not a rule of law, the courts

shall not base a conviction on a confession without corroboration. T h u s

each and every circumstance mentioned in the confessional statement

need not be materially corroborated.

E. Exceptions to the Hearsay Evidence

Sections 32 a n d 33 lay down exceptions to the general rule that

hearsay evidence shall not be a d m i t t e d . Clause (i) to section 32

makes relevant the statement of a person since deceased to prove the

cause a n d circumstances of his d e a t h . T h e principles laid down

in this regard by the Privy Council in Narayana Swami v. Emperor*2

have all along been followed by the courts. While agreeing

that no exhaustive or inflexible rules for recording a dying declara

tion can be laid down, the Rajasthan H i g h Court in Hari Ram v.

State*3 laid down the following rules to be normally followed for the

purpose:

(1) T h e magistrate, the police officer, the doctor or any person

recording such dying declaration must first satisfy himself that

the declarant is in senses; if not so, h e must make a note t h a t

in his opinion, the declarant was not in senses.

(2) T h e person recording the dying declaration must ascertain

whether the declarant is in a position to speak coherently.

(3) After getting himself so satisfied, he must proceed putting general

questions eliciting the reply a n d should, as far as possible,

record the n a t u r e of questions p u t , so t h a t the court m a y j u d g e

them.

40. Supra note 33, at 7.

41. A.LR. 1963 S.C. 1094.

42. A.I.R. 1939 P.C. 47.

43. A.LR, 1965 Raj. 130.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

200 ANNUAL SURVEY OF INDIAN LAW

(4) So far as possible, the dying declaration should be recorded in

the words of the declarant.

(5) If the injured is not in a position to speak by mouth in a cohe

rent way, he may be put short questions and his answers given

by gestures may be noted. It is imperative in such a case

that the gestures of the injured person signifying the answer

given by him should find an appropriate mention.

(6) Under certain circumstances, putting of leading questions may

be permitted.

(7) The person recording the dying declaration must see that it

is not prompted and must therefore exclude all the relatives

and other persons from that place.

(8) The dying declaration should, if the circumstances are such,

be read over to the maker and his signatures or thumb impres

sion obtained or appended.

In Pompaih v. State of Mysore,4t the Supreme Court, however, laid

dawn a strict rule as regards the evidentiary value of dying declara

tion. According to the Supreme Court, a dying declaration is to be

subjected to a close scrutiny considering always the fact that it was made

in the absence of the accused who had no opportunity to test its veracity

by cross-examination. Further, the court must satisfy itself that the

declaration was truthful. These observations of the Supreme Court

clearly imply that even if there is a small lacuna in following the rules

meant for recording a dying declaration, it should be rejected. In the

light of the above, the Hari Ram case, which upheld the dying declara

tion although the questions put were not recorded, seems to have laid

down a doubtful proposition of law.

III. MEANS OF PROOF

A. Oral Evidence Regarding Terms of a Document

According to section 91 of the Evidence Act, no evidence, except

the document itself or secondary evidence wherever admissible, is ad

missible to prove the terms of a contract, grant or disposition of property

reduced to writing either under the provisions of law or otherwise. Sec

tion 92, which is in substance part of section 91, bars oral evidence to

contradict, vary or add to or substract from the terms and conditions of

a transaction similarly reduced to writing. Clarifying the scope of

section 92, the Patna High Court in Ram Marayan v. Kedar JVath*6 ob

served that both section 92 and section 91 speak of the "terms" of a

contract, but the question as to who are the parties to such a contract

is not a term of the contract. What is excluded is the oral evidence

44. A.LR. 1965 S.C. 939.

45. A.I.R. 1965 Pat. 463.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

LAW OF EVIDENCE 201

designed to contradict, vary, a d d to or substract the terms of the

contract agreed upon by the parties a n d not who are the parties to the

contract.

B. Examination of Witnesses

T h e trend of judicial opinion seems to be to give m a x i m u m disc

retion to the court concerned so far as judging the credibility of t h e wit

ness is concerned. T h e following observations of the Supreme Court

in Ramchandra v. Champabai^ are significant in this c o n t e x t :

In order to judge the credibility of the witnesses, the Court is not confined

only to the way in which the wrtnesses have deposed or to the demeanour of

the witnesses but it is open to it to look into the surrounding circumstances as

well as the probabilities so that it may be able to form a correct idea of the

trustworthiness of the witnesses.47

During the year u n d e r review, the courts only reiterated the estab

lished principles in respect of examination of witnesses. T h e Supreme

Court in Bombay Corporation v. Pancham*8 observed t h a t just as it is not

open to a court to compel a party to m a k e a particular kind of pleading

or to amend his pleading, so also it is beyond its competence to virtually

oblige a party to examine any p a r t i c u l a r witness. Similarly, the rule

that no evidence shall be used against a person unless it has been sub

jected to cross-examination by him or t h a t such a n opportunity has been

declined by him has been upheld. 4 9 W h e n it is intended to contradict

a witness by any writing, his attention must, before the writing can be

proved, be called to those parts of it which are to be used for t h e purpose

of contradicting him. 5 0 T h e court in its discretion may permit t h e

party calling a witness to p u t any question to h i m w h i c h might be p u t to

him by the adverse party in cross-examination. 5 1 But such witnesses

cannot b e cross-examined by the co-complainants w h o did not call h i m

as their witness. T h e court, however, u n d e r section 165, has unlimited

powers to p u t any question to a witness or to order h i m to p r o d u c e docu

ments either suo moto or o n t h e suggestion of t h e complainants. 5 2

C. Privileged Documents

T h e state has the privilege to refuse to show or produce any un-

46. A.LR. 1965 S.C. 354.

47. Id. at 365.

48. A.I.R. 1965 S.C. 1008.

49. Haridas v. Indian Cable Co., A.I.R. 1965 Cal. 368; Shyam Singh v. D.LG.

of Police, AJ.R. 1965 Raj. 140.

50. Section 145, Indian Evidence Act. See also Pangi Jogi Naik v. State, A.I.R,

1965 Orissa 205; Jitendra Nath v. Sushilendra Nath, A.I.R. 1965 Cal. 328.

51. Section 154, Indian Evidence Act.

52. Giriraj Singh v. State, A.LR. 1965 All. 131.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

202 ANNUAL SURVEY OF INDIAN LAW

published official record relating to t h e affairs of t h e state 5 3 or to dis

close any official communication if it is against public interest. 5 4 While

determining the state privilege, t h e English courts have mostly them

selves looked into t h e state papers. 5 5 Similarly, the Supreme Court of

the U n i t e d States has also held that the determination of the privilege

is a judicial function. 5 6 A very interesting point came u p before the

H i g h Court of J a m m u a n d Kashmir in State of J,K. v. Anwar Ahmed

AftaP7 that once it is a c c e p t e d t h a t the previsions of Indian Evidence

Act apply in principle to the proceedings before a Commission consti

tuted u n d e r the J a m m u a n d Kashmir Commission of Enquiry Act, does

it imply t h a t section 123 of I n d i a n Evidence Act also applies to the pro

ceedings before the Commission and, if so, w h e t h e r the state can accor

dingly withhold t h e production of documents before the Commission.

T h e Cburt held t h a t while t h e principles of Evidence Act m a y be appli

cable to t h e evidence p r o d u c e d before t h e tribunal, it would not be pro

per or in parity with reason to infer that even the exceptions contained

in t h e Evidence A c t would also be applicable. 5 8 T h e Court further

observed t h a t where the Act has itself impliedly excluded the doctrine

of state privilege to withold documents from t h e ambit of the jurisdic

tion of the tribunal, no privilege by the state can be claimed under sec

tion 123. I t is difficult to agree with the views expressed by the High

Court. T h e provisions of Evidence Act, if applied, must be deemed to

b e applicable as a whole a n d not in a pick a n d choose manner. Sec

tion 123 lays down a general principle of the law of evidence. It is,

therefore, difficult to think how some principles apply to the tribunal

a n d some, viz., the one contained in section 123, does not.

IV. A D D U C T I O N AND ASSESSMENT OF EVIDENCE

I t is a n established principle of law that one w h o asserts a fact must

himself prove it unless t h e b u r d e n is shifted to t h e other party. T h e

53. The Allahabad High Court in Mahabirji Mandir v. Prem Narain, A.I.R. 1965

All. 494, observed:

The term 'affairs of state' is a general one, but it can't include all that is con

tained in the records. Where an open enquiry is made, statement recorded during

the open enquiry cannot be deemed to be confidential and similarly an applica

tion or a complaint made by a person cannot be held to relate to the 'affairs of

the state'.

54. V. Dasan v. State of Kerala, A.I.R. 1965 Ker. 63, where it was held that dis

closing confidential report by the police against the petitioner amounts to an act to

the detriment of public interest.

55. Duncan v. Cammell Laird, (1942) A.C. 624, where the House of Lords

clarified the position in this regard.

56. U.S. v. Raynoldst 345 U.S. 1; Jenks v. U.S., 353 U.S. 657.

57. A.I.R. 1965 J. & K. 75.

58. The Court observed that section 123 of the Evidence Act is an exception to

the general rule of admissibility of evidence.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

LAW OF EVIDENCE 203

Supreme Court during the year under survey h a d occasions to reiterate

a n d work out the principle in a n u m b e r of cases. I n Mahendra v. Sushila,m

the Court observed : " W h e n the law places the burden of proof upon

a party, it requires that p a r t y to a d d u c e evidence in support of his allega

tion unless h e is relieved of the necessity to ds> so by reason of admissions

made by him or in the evidence a d d u c e d on behalf of his o p p o n e n t . " 0 0

I n Sheopal Singh v. Ram Pratap,Gl it again observed: " T h e b u r d e n of

proof as a matter of law a n d as a m a t t e r of adducing evidence is on the

respondent who seeks to get the election set aside, a n d to establish corrupt

practice, but if h e adduces sufficient evidence, as in this case we are

satisfied, the b u r d e n of adducing evidence shifts on to the appellant." 0 2

A controversial test to determine the onus of proof was laid down in

Bibhuti Bhusan v. Sadhan Chandra^ where t h e Court observed t h a t the

ordinary rule t h a t one w h o asserts a fact must himself prove it has no

application to cases where the true b o u n d a r y of a particular land is

under dispute. T h e Court observed t h a t it was the duty of either p a r t y

to aid the court in ascertaining t h e true b o u n d a r y to i m p a r t substantial

justice. Gould t h e n one conclude t h a t as substantial justice being all

that is necessary, the provisions of Evidence Act are neither mandatory

nor bind the court to proceed acccrding to t h e m ? T h e point is d e b a

table a n d it is submitted that the courts cannot do w h a t the statute does

not permit t h e m to d o a n d as such the well established rules regarding

the onus cannot be ignored howsoever important substantial justice

as a criterion may be.

V. PRESUMPTIONS

Most of the cases under this h e a d related to adverse presumptions. 6 4

I n State of Punjab v. MJs Modern Cultivators^ the Supreme Court laid

down that where a party is in normal a n d natural possession of the docu

ments and in spite of the orders of the court does not produce them, a n

adverse presumption can be drawn that if produced they would have gone

against that party. I n this case, the Court gave relief to the respon

dents who suffered loss on account of a b r e a c h in the canal. Since the

State did not produce the documents, negligence on their p a r t in m a i n

taining the canal was presumed. I n Tejendra v. Tripura Administration,m

the Court held that where the accused is otherwise entitled to challenge

the prosecution witness, for example, on the basis that h e is not a n in-

59. A.I.R. 1965 S.C. 364.

60. Id. at 405, per Mudholkar, J.

61. A.I.R. 1965 S.C. 677.

62. Id. at 679, per Subba Rao, J.

63. A.I.R. 1965 Cal. 199.

64. See Illustration (g) to section 114, Indian Evidence Act.

65. A.I.R. 1965 S.C. 17.

66. A.I.R. 1965 Tripura 45.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

204 ANNUAL SURVEY OF INDIAN LAW

dependent witness, no adverse presumption can be drawn against the

prosecution which does examine such a witness. Not going into the

merits of any particular case, it m a y b e submitted that section 114 is

quite independent of other provisions of the Evidence Act or any other

law a n d h e n c e the argument that a party, besides under section 114,

could also seek a defence under other provisions of law, does not debar

such a p a r t y from invoking a defence under section 114 as well.

Sections 107 a n d 108 deal with presumption of continuance of life.

W h e n the question is w h e t h e r a person is alive or dead a n d it is shown

that h e was alive within the preceding thirty years, the burden of proving

t h a t h e is d e a d is on the person w h o affirms it. But this rule is subject

to a proviso that if a m a n has not been heard of f>r seven years by those

who would naturally have h e a r d of h i m h a d h e been olive, the burden

of proving that h e is alive is shifted to the person who affirms it. I n

H.J. Bhagat v. LJ. Cotpn.,67 the M a d r a s High Court considered two

very important points, firstly, to w h a t extent English authorities support

the presumption raised by section 108, a n d secondly, whether such

facts that a person did not claim his dividend or that h e did not apply

for his monthly allowance which was the sole means of his subsistence,

establish a presumption of the d e a t h of a person. No doubt, section

108 is founded u p o n the principles of English law but, as the Court

observed, it is doubtful if English authorities on the point can be followed

in India. T h e reason, as it seems, is that in our country, it is not unusual

for impressionable persons, even though they might be well off, to sud

denly forsake this world a n d to disappear upon some presumed religious

a n d spiritual quest. 6 8 U p o n the second count, the Court observed that

it would be most unsafe a n d u n w a r r a n t e d by facts a n d probabilities to

d r a w a n inference that a m a n must be presumed to be dead on or about

a particular d a t e if he fails to d r a w his allowance for support. Thus,

inspite of t h e fact t h a t the section in principle is based on the English

common law, it has b e e n differently applied in India.

VI. CONCLUDING OBSERVATION

T h e tendency of the courts while interpreting the provisions of

the Evidence Act has been to uphold the established principles. While

in matters like admission a n d confession, it has been desirable to accept

the well-laid rules of law in order to a d d predictability a n d certainty;

in matters of presumptions, evidence of experts a n d corrobora

tion, it is advisable that the courts lay down clear tests of admissibility.

Different conclusions have, of late, been arrived at by courts in respect

of to take a few examples, sections 108, 114, 133 a n d 134. Law, thus,

has remained u n c e r t a i n on these points. O n e of the methods to import

67. A.I.R. 1965 Mad. 440.

68. Id. at 442.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

LAW OF EVIDENCE 205

certainty a n d predictability would be to develop a practice that the

courts should seldom deviate, unless on very strong grounds involving

social a n d economic policies, from their earlier constructions of law.

T h e uncertain a n d speculative character of these sections was scmehow

not brought before the Fifth Law Commission w h i c h considered the

admissibility of hearsay evidence a n d secondary evidence of documents. 6 9

T h e courts in their zeal to subscribe to t h e "circumstances of

individual c a s e " have a t times stretched the law beyond any possible

h u m a n imagination.

I n our society where moral norms a n d social tenets are deep a n d

strict, bald provisions like sections 114, 123 a n d 134 bring unbridled

speculation a n d throw open the game of hide a n d seek. T h e I n d i a n

Evidence Act, effective since 1872 with very few amendments, stands in

need of thorough revision 70 specially in view of the facts that the recent

progress in technology, communication a n d transport is tending to

overhaul the Indian society a n d t h a t social attitudes to the environments

are fast changing. T h e Law Commission has not examined the I n d i a n

Evidence Act in its entirety a n d its recommendations relate only to the

examination of a few provisions of the Act. Social conditions, economic

needs a n d political situations prevailing in I n d i a a r o u n d 1872 have

undergone immense change. A sociological study would reveal t h a t

our law of evidence has been an outcome of feudal society which be

lieved in categorisation a n d re categorisation of h u m a n personality,

mind a n d conscience. Provisions like relevancy of character evidence

do not fit in with the modern notions which are averse to categorisation.

T h e revision of the law of evidence will have to take into account the

modern m a n whose impulses, motivations a n d actions are governed

by the complex a n d diverse conditions of a transitional if not a n indus

trial society. I t is to be hoped that the Law Commission will soon

undertake a comprehensive revision of the entire Act.

69. 1 Law Commission of India, Fourteenth Report: Reforms of Judicial Adminis-

tration 516-19 (1958).

70. Id. at 516.

www.ili.ac.in The Indian Law Institute

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (120)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- KUWAIT Companies Contact DetailsDocument18 pagesKUWAIT Companies Contact DetailsYAGHMOURE ABDALRAHMAN82% (34)

- Formulir Umpan-Balik 360 DerajatDocument3 pagesFormulir Umpan-Balik 360 DerajatRuang Print100% (2)

- Ffective Emand Etters: S P & A LDocument44 pagesFfective Emand Etters: S P & A Lshrinivas legal100% (1)

- Legal Education and ResearchDocument279 pagesLegal Education and Researchsemarang100% (1)

- Trial ProcedureDocument115 pagesTrial ProcedureAnonymous tOgAKZ8No ratings yet

- 009 - 1978 - Criminal Law and ProcedureDocument54 pages009 - 1978 - Criminal Law and ProcedureBhumika BarejaNo ratings yet

- Criminal ProcedureDocument47 pagesCriminal Procedureshrinivas legalNo ratings yet

- Hindi-English Enviroment Legal Handbook PDFDocument85 pagesHindi-English Enviroment Legal Handbook PDFshrinivas legalNo ratings yet

- CPC Q A Lecture Notes 1 2 3 4 5Document17 pagesCPC Q A Lecture Notes 1 2 3 4 5shrinivas legal100% (1)

- Contract Labour Regulation and Abolition Act 1970Document20 pagesContract Labour Regulation and Abolition Act 1970subhasishmajumdarNo ratings yet

- 3-Perpetual Injunction - by SMT E PrathibaDocument16 pages3-Perpetual Injunction - by SMT E Prathibashrinivas legalNo ratings yet

- Schedule of IpcDocument100 pagesSchedule of IpcSoundharya JayaramanNo ratings yet

- Industrialemployment (Standingorders) 1centralrules1946Document21 pagesIndustrialemployment (Standingorders) 1centralrules1946Hemanth KumarNo ratings yet

- Industrialemployment (Standingorders) 1centralrules1946Document21 pagesIndustrialemployment (Standingorders) 1centralrules1946Hemanth KumarNo ratings yet

- Basic Concept of CRPC 1898 Part-02 PDFDocument35 pagesBasic Concept of CRPC 1898 Part-02 PDFAnurag KumarNo ratings yet

- Criminology For Competitions PDFDocument202 pagesCriminology For Competitions PDFshrinivas legal100% (1)

- Trial Before CourtDocument33 pagesTrial Before CourtShivraj PuggalNo ratings yet

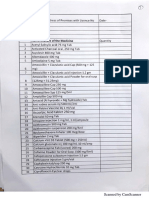

- Regarding Survey Data of Critical Drugs PDFDocument5 pagesRegarding Survey Data of Critical Drugs PDFshrinivas legalNo ratings yet

- Hindi-English Enviroment Legal Handbook PDFDocument85 pagesHindi-English Enviroment Legal Handbook PDFshrinivas legalNo ratings yet

- All About Appeals Under Code of Criminal ProcedureDocument6 pagesAll About Appeals Under Code of Criminal Procedureshrinivas legalNo ratings yet

- Sessions TrialDocument31 pagesSessions TrialsabarishgandhiNo ratings yet

- 10 - Chapter 5Document74 pages10 - Chapter 5shrinivas legalNo ratings yet

- Ip Panorama 5 Learning PointsDocument35 pagesIp Panorama 5 Learning PointsMilind Ramchandra DesaiNo ratings yet

- Title NO.34 (As Per Workshop List Title No34 PDFDocument24 pagesTitle NO.34 (As Per Workshop List Title No34 PDFshrinivas legalNo ratings yet

- C 123 ErtDocument67 pagesC 123 ErtSwarnim PandeyNo ratings yet

- Ethics Notes in HindiDocument123 pagesEthics Notes in Hindishrinivas legalNo ratings yet

- Cyber Law Notes PDFDocument579 pagesCyber Law Notes PDFAdv NesamudheenNo ratings yet

- Manual of Trade Marks: Practice & ProcedureDocument143 pagesManual of Trade Marks: Practice & ProcedureSaurabh KumarNo ratings yet

- Investigation - Coercive - Measures Arrest Criminal Law PDFDocument230 pagesInvestigation - Coercive - Measures Arrest Criminal Law PDFshrinivas legalNo ratings yet

- Workman Compensation ActDocument38 pagesWorkman Compensation ActsridharpalledaNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceutical Validation: Presented By: Bharatlal Sain 1 M.Pharm PharmaceuticsDocument32 pagesPharmaceutical Validation: Presented By: Bharatlal Sain 1 M.Pharm PharmaceuticsRaman KumarNo ratings yet

- Manaswe, D.R. 201508059.Document16 pagesManaswe, D.R. 201508059.Desmond ManasweNo ratings yet

- BL Saco ShippingDocument1 pageBL Saco ShippingvinicioNo ratings yet

- B1562412319 PDFDocument202 pagesB1562412319 PDFAnanthu KGNo ratings yet

- Understanding The Self Activity 4Document2 pagesUnderstanding The Self Activity 4Asteria GojoNo ratings yet

- GRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log JUNE 5-9, 2017 (WEEK 1)Document6 pagesGRADES 1 To 12 Daily Lesson Log JUNE 5-9, 2017 (WEEK 1)Ghie MoralesNo ratings yet

- MIS 320 Module Four Case Study Analysis Guidelines and Rubric Organizational E-Commerce Case Study Analysis: AmazonDocument2 pagesMIS 320 Module Four Case Study Analysis Guidelines and Rubric Organizational E-Commerce Case Study Analysis: AmazonghanaNo ratings yet

- What Is The Prisoner's Dilemma?Document4 pagesWhat Is The Prisoner's Dilemma?Mihaela VădeanuNo ratings yet

- CQI&IRCA CERTIFIED ISO 90012015 QMS AUDITOR LEAD AUDITOR - Singapore Quality InstituteDocument1 pageCQI&IRCA CERTIFIED ISO 90012015 QMS AUDITOR LEAD AUDITOR - Singapore Quality InstituteYen Ling NgNo ratings yet

- Consignment CH 1Document23 pagesConsignment CH 1david faraonNo ratings yet

- STD 8 - PA2 Portion, Time Table & Blue PrintDocument2 pagesSTD 8 - PA2 Portion, Time Table & Blue Printrajesh rajNo ratings yet

- Internship Report Course Code CSE (I.e. FINAL YEAR) Magus Customer Dialogue M Submitted by Michael Mario 15CS052 Summer 2018 16-07-2018Document11 pagesInternship Report Course Code CSE (I.e. FINAL YEAR) Magus Customer Dialogue M Submitted by Michael Mario 15CS052 Summer 2018 16-07-2018vivekgandhi7k7No ratings yet

- Generating Jobs-To-Be-Done InsightsDocument3 pagesGenerating Jobs-To-Be-Done InsightsFerry TimothyNo ratings yet

- Easytek: User GuideDocument120 pagesEasytek: User GuideaxisNo ratings yet

- LSC Malta Application FormDocument8 pagesLSC Malta Application FormChouaib AbNo ratings yet

- Features of Language According To Charles HockettDocument1 pageFeatures of Language According To Charles HockettMarc Jalen ReladorNo ratings yet

- Organization Vision and Visionary OrganizationsDocument24 pagesOrganization Vision and Visionary OrganizationsHemlata KaleNo ratings yet

- Aligning Compensation Strategy With Business Strategy: A Case Study of A Company Within The Service IndustryDocument62 pagesAligning Compensation Strategy With Business Strategy: A Case Study of A Company Within The Service IndustryJerome Formalejo,No ratings yet

- 5K To 10K Training PlanDocument1 page5K To 10K Training PlanAaron GrantNo ratings yet

- Air Cargo GuideDocument211 pagesAir Cargo Guideulya100% (1)

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Huma1301.004.11s Taught by Peter Ingrao (Jingrao)Document10 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Huma1301.004.11s Taught by Peter Ingrao (Jingrao)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- Clinical Research Profesionals in IndiaDocument5 pagesClinical Research Profesionals in Indiasng1No ratings yet

- Fir, It' S Objective and Effect of Delay in Fir Shudhanshu RanjanDocument7 pagesFir, It' S Objective and Effect of Delay in Fir Shudhanshu RanjanPrerak RajNo ratings yet

- 7 Steps To Building Your Personal BrandDocument5 pages7 Steps To Building Your Personal BrandGladz C CadaguitNo ratings yet

- Drama - Putting A Script Through Its PacesDocument2 pagesDrama - Putting A Script Through Its PacesJoannaTmszNo ratings yet

- Course Syllabus TTL2 ScienceDocument8 pagesCourse Syllabus TTL2 ScienceMelan Joy Dela Cruz100% (1)

- Wangel, J. Exploring Social Structure and Agency in Backcasting StudiesDocument11 pagesWangel, J. Exploring Social Structure and Agency in Backcasting StudiesBtc CryptoNo ratings yet

- The DAV MovementDocument34 pagesThe DAV MovementrajivNo ratings yet