Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Use of The Structured Descriptive Assessment With Typically Developing Children

Use of The Structured Descriptive Assessment With Typically Developing Children

Uploaded by

PSIQUECRISTHIAN77Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Use of The Structured Descriptive Assessment With Typically Developing Children

Use of The Structured Descriptive Assessment With Typically Developing Children

Uploaded by

PSIQUECRISTHIAN77Copyright:

Available Formats

Behavior Modification

http://bmo.sagepub.com/

Use of the Structured Descriptive Assessment With Typically Developing Children

Cynthia M. Anderson, Carie L. English and Theresa M. Hedrick

Behav Modif 2006 30: 352

DOI: 10.1177/0145445504264750

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://bmo.sagepub.com/content/30/3/352

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for Behavior Modification can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://bmo.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://bmo.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://bmo.sagepub.com/content/30/3/352.refs.html

>> Version of Record - Mar 30, 2006

What is This?

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

BEHAVIOR

10.1177/0145445504264750

Anderson et al.

MODIFICATION

/ STRUCTURED/ May

DESCRIPTIVE

2006 ASSESSMENT

Use of the Structured Descriptive

Assessment With Typically

Developing Children

CYNTHIA M. ANDERSON

CARIE L. ENGLISH

THERESA M. HEDRICK

West Virginia University

To date, only a limited number of studies have focused on functional assessment with typically

developing populations. The most commonly reported method of functional assessment with this

population seems to be descriptive assessment; however, the methods used in the descriptive

assessment often are unclear. This is unfortunate as researchers and practitioners often are left

with little guidance as to how to conduct a functional assessment with typically developing chil-

dren. The purpose of this study was to determine whether the structured descriptive assessment

(SDA) might be used with typically developing children. Four children with problem behavior

participated in the study, and hypotheses about functional relations were developed for all chil-

dren. Furthermore, efficacious interventions were developed and implemented for 2 children

based on the results of the SDA.

Keywords: functional assessment; interventions; functionally derived interventions; problem

behavior; day care

The utility of a pretreatment functional assessment for identifying

environmental variables affecting problem behavior is well estab-

lished (see the special issue on functional assessment in Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 1994, Vol. 27). To date, however, the vast

majority of research on functional assessment has been conducted

with individuals with developmental disabilities; relatively little

research exists to guide practitioners working with typically develop-

ing children—children not diagnosed with mental retardation or some

other developmental delay (Fox, Conroy, & Heckaman, 1998; Hanley,

AUTHORS’ NOTE: Carie L. English is now at the University of South Florida.

BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION, Vol. 30 No. 3, May 2006 352-378

DOI: 10.1177/0145445504264750

© 2006 Sage Publications

352

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 353

Iwata, & McCord, 2003; Heckaman, Conroy, Fox, & Chait, 2000;

Sasso, Conroy, Stichter, & Fox, 2001). In a review of the literature,

Sasso et al. identified only 18 published studies using pretreatment

functional assessment with children identified as having or being at

risk for an emotional or behavioral disorder. This is unfortunate

because, as pointed out by Lewis and Sugai (1996), the extent to

which the methods used in studies with individuals with disabilities

will be efficacious with different behavior problems (e.g., low fre-

quency responses) and in different settings (e.g., schools or homes vs.

inpatient hospitals) is unclear. Several studies have highlighted the

need to include a wider variety of variables in functional assessment

(e.g., Carr, 1994; Carr, Yarbrough, & Langdon, 1997; Mace, Lalli,

Pinter Lalli, & Shea, 1993), and this seems especially important when

working with typically developing children. To illustrate, Lewis and

Sugai (1996) demonstrated that peer attention, an environmental

event not typically assessed in functional assessments, might maintain

problem behavior exhibited by some children.

Although only a few studies have examined functional assessment

with typically developing children, increased attention has been

focused on this population in recent years. Most research has used

descriptive functional assessments, although a small number of stud-

ies have used experimental manipulations to test hypotheses derived

from descriptive assessments.

Descriptive assessments typically are conducted in the natural

environment, and environmental variables are not manipulated.

Instead, descriptive assessments involve recording instances of the

target behavior and environmental events that precede or follow the

behavior. The most common method of descriptive assessment is

antecedent behavior consequence (ABC) recording (e.g., Lewis &

Sugai, 1996). Most descriptive assessments focus on both antecedent

and consequent events (e.g., Lewis & Sugai, 1996); however, some

researchers have focused primarily on antecedent variables in their

assessment. For example, Ervin et al. (2000) conducted descriptive

assessments to identify classroom and curricular variables that often

evoked problem behavior exhibited by three adolescents diagnosed

with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Variables

found to evoke problem behavior included specific classes (e.g., sci-

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

354 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

ence) or teaching strategies (e.g., lectures vs. active, hands-on partici-

pation). Although descriptive assessments are the most commonly

reported method of functional assessment with this population, the

methods used in the assessment vary widely across studies, and the

specific methods used in the assessment often are unclear. To illus-

trate, Ervin et al. (2000) noted that descriptive data were collected

using a behavior tracking form adapted from another measure but did

not delineate the manner in which data were collected (e.g., fre-

quency, partial-interval), the dependent variables coded, or how

observations were scheduled. Similarly, Lewis and Sugai (1996)

reported that direct observations were conducted using an ABC for-

mat, but the environmental events observed, the method of recording

used, and the frequency and duration of observations were not delin-

eated. In the literature review conducted by Sasso et al. (2001), 83% of

studies reporting a descriptive functional assessment did not include a

description of the methods used in the assessment.

An alternative to descriptive assessments are experimental func-

tional assessments (i.e., functional analyses), which involve manipu-

lation of one or more environmental variables (e.g., analog functional

analysis; Iwata, Dorsey, Slifer, Bauman, & Richman, 1994). Experi-

mental functional analyses typically are conducted in a systematic

fashion using a single-subject design and therefore allow for demon-

stration of a causal relation between environmental events and prob-

lem behavior. Although experimental analyses are reported fairly

often in empirical studies with individuals with disabilities, they are

used only rarely with typically developing populations (Hanley et al.,

2003). Experimental functional analyses likely are used infrequently

with typically developing children as many researchers and practitio-

ners view the range of variables manipulated in experimental analyses

as restrictive and question the external validity of hypotheses derived

from assessments conducted in atypical settings (e.g., laboratories)

by atypical care providers (Anderson, Freeman, & Scotti, 1999; Carr

et al., 1997; Mace et al., 1993). Of studies reporting an experimental

functional analysis with typically developing children, most did not

involve an analog functional analysis (as is the most common method

of experimental functional analysis with people with disabilities;

Hanley et al., 2003) but instead used brief contingency reversals to

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 355

demonstrate the relation between environmental events identified in a

descriptive assessment and problem behavior (e.g., Broussard &

Northup, 1995; Dunlap et al., 1993; Harding et al., 1999; Lewis &

Sugai, 1996; Umbreit, 1995). For example, Dunlap et al. (1993)

developed hypotheses about environmental manipulations that might

decrease problem behavior based on descriptive assessments (the

manner in which the descriptive assessment was conducted was not

described) and interviews for five children exhibiting problem behav-

ior. Three hypotheses were developed for most participants, one iden-

tifying strategies to increase appropriate behavior (e.g., delivering

verbal praise for appropriate behavior), one focusing on strategies to

decrease inappropriate behavior (e.g., ignoring problem behavior),

and a third focusing on either an antecedent manipulation or a self-

control strategy (e.g., task interspersal, teaching the child to evaluate

his or her verbal statements). Each hypothesis then was evaluated sys-

tematically using a brief reversal design. Although the use of experi-

mental manipulations to demonstrate the validity of hypotheses

derived from descriptive assessments is a useful strategy, the extent to

which findings of these studies and others can be replicated or used by

practitioners seeking guidance in conducting functional assessments

is limited because, as noted earlier, the specific strategies used to con-

duct descriptive assessments rarely are described with precision.

Given that only a small number of studies report the use of func-

tional assessment with typically developing children, this lack of

methodological clarity is troubling. Researchers wishing to further

validate or refine measures and clinicians searching for efficacious

functional assessment methods are left with little guidance as to how a

descriptive assessment might best be conducted with this population.

Clearly, more research is needed to identify specific methods of func-

tional assessment that might be useful for typically developing chil-

dren. The current study was designed to evaluate the utility of the SDA

(Anderson & Long, 2002) for use with typically developing children.

The SDA involves conducting observations under specific stimulus

conditions and thus limits the ambiguity present in many descriptive

assessments. Because previous research (Anderson & Long, 2002;

Freeman, Anderson, & Scotti, 2000) has demonstrated the utility of

the SDA with individuals with disabilities in community settings, the

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

356 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

next logical step is to evaluate its utility with typically developing

populations.

EXPERIMENT 1

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Four children referred for the assessment and treatment of problem

behavior participated. Prior to conducting the study, all caregivers

were interviewed to determine preferred tangible items and to identify

caregiver hypotheses about the function(s) of their child’s problem

behavior. Art1 was a 4-year-old, typically developing boy who exhib-

ited aggressive and disruptive behavior. Art’s aggression was directed

primarily toward his younger brother, resulting in scratches and

bruises on his sibling’s face. Art’s SDA was conducted at home, and

his father conducted all sessions during the preassessment interview.

Art’s father suggested that problem behavior most likely occurred

because Art was jealous of his younger brother. Don was a 6-year-old,

typically developing boy who exhibited aggression, disruption, and

self-injurious behavior (SIB). Don’s SDA was conducted at his day

care. There were three adult teachers at the day care, and all were

involved in conducting the SDA. The supervisor of Don’s day care

suggested that problem behavior might be occurring because Don was

angry at his parents for leaving him at day care. Pat was a 4-year-old,

typically developing girl who also exhibited aggression, disruption,

and SIB. Pat lived at home with her mother, who was diagnosed with

borderline mental retardation. Due to a history of suspected abuse and

neglect, at the time we worked with Pat direct-care staff workers were

in the home 24 hours a day to supervise parent-child interactions and

to train Pat’s mother in basic child care and daily living skills. Pat’s

SDA was conducted at home, and her mother conducted the SDA,

although direct-care staff workers occasionally interacted with Pat

during the assessment. Pat’s mother reported that Pat exhibited prob-

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 357

lem behavior because direct-care staff members were mean; direct-

care staff workers suggested that Pat suffered from severe mental ill-

ness, such as bipolar disorder or schizophrenia and that this was the

reason she exhibited problem behavior. Tim was a 6-year-old, typi-

cally developing boy referred for assessment and treatment of aggres-

sive and disruptive behavior. Tim’s SDA was conducted at his day

care, and the two teachers working in the day care conducted the

assessment. Tim was at risk for being expelled from day care due to

the severity of his behavior. Prior to beginning our assessment, Tim

had been suspended from day care five times for behaviors such as

threatening peers and adults (making stabbing gestures with scissors),

punching peers, and attempting to set a fire at the day care. Tim’s day

care supervisor believed that Tim’s problem behavior was the result of

significant mental illness and suspected that Tim suffered from

bipolar disorder.

Response Definitions, Data Collection,

and Interobserver Agreement

Definitions for problem behavior were based on interviews con-

ducted with caregivers and on direct observations conducted prior to

beginning the study. Problem behaviors included aggression, defined

as hitting, kicking, pinching, scratching, biting, and throwing objects

that landed within 1 ft of a person; disruption, defined as throwing

objects, ripping objects, and knocking over furniture; and self-injury

(Don and Pat only), defined as head banging and head hitting. All tar-

get child behaviors were scored using continuous frequency

recording.

All caregiver responses were coded on an interval-by-interval basis

using continuous recording across consecutive 5-s intervals. To facili-

tate coding of caregiver responses, all sessions were coded at least

twice. Initially, the following responses were coded: prompts, atten-

tion delivery, tangible delivery, attention deprivation, escape, tangible

removal, and time-out (Tim only). Prompts were defined as an

instruction to complete an action, including physical prompts, and an

ongoing instructional context. Attention delivery was scored as occur-

ring when the therapist interacted with the participant in a nonin-

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

358 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

structional manner. This included reprimands, verbal statements

toward the child, and physical interaction. Tangible delivery was

defined as allowing the participant access to the predefined, preferred

stimulus. Tangible delivery was coded if the caregiver handed the item

to the child, told the child that he or she could have it, or simply

allowed the child to independently access the item. Attention depriva-

tion was defined as the absence of attention for a complete interval.

Escape was scored if the participant was not engaged in a previously

requested task and prompts to engage in the task were not presented

for the entire interval. Tangible deprivation was defined as the

removal of a preferred tangible for at least one complete interval.

Time-out was coded only for Tim. Although all caregivers reported

using time-out, it was observed only with Tim. Time-out was defined

as the caregiver’s telling Tim to go to time-out and then placing him in

the designated time-out chair. Time-out continued to be coded for as

long as Tim remained in the designated chair.

After coding caregiver responses as described above, sessions were

rescored to provide more information about caregiver prompts and

attention delivery. Prompts were coded as either physical prompts,

prompts requiring movement to complete, prompts that did not

require movement to complete, instructional context with the care-

giver present, and instructional context with caregiver absent. Physi-

cal prompts were defined as requests involving hand-over-hand guid-

ance (e.g., the caregiver physically picked the child up and walked

him or her down the hall); prompts requiring movement were requests

that, to comply with, the child would have to physically move from

one location to another (e.g., putting toys away); and prompts not

requiring physical movement could be completed in place (e.g., table

work). Finally, the presence of an instructional context (e.g., circle

time, table work) was coded as either one in which the caregiver was

within 2 ft of the child (caregiver present) or further than 2 ft from the

child (caregiver absent). Attention delivery was scored as either

positive/neutral attention or negative attention.

Peer responses were coded for all target children except Pat (as no

peers were present in her home). Peer responses were coded using par-

tial interval coding across continuous 5-s intervals. Peer responses

coded included positive/neutral attention delivery and ongoing inter-

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 359

action. Positive/neutral attention was defined as verbal statements

directed toward the child (e.g., “Want to play?” or “Look at this.”) or

physical interaction (e.g., hugging, holding hands). Negative atten-

tion was defined as aggression directed toward the target child or

derogatory verbal statements (e.g., “I hate you,” “Stop pushing,” “Cut

it out.”). Ongoing interaction was coded when the target child was

actively engaged with another child for two or more consecutive inter-

vals. Parallel play and simply sitting together was not coded as ongo-

ing interaction. Examples of ongoing interaction included building a

block tower together or working together on a work sheet.

Caregiver and peer behaviors were coded as soon as they occurred,

and the order of occurrence was recorded if they occurred within the

same interval as a child problem behavior. When a caregiver or peer

response continued to occur across adjacent intervals, it was rescored

in each new interval until the event ended. For example, if the care-

giver continued to sit with a child on his or her lap in consecutive inter-

vals, positive/neutral attention was scored as soon as it occurred and in

each subsequent interval until attention delivery ceased. If both the

caregiver or peer and participant continued to respond across inter-

vals, the original order of responding was maintained at the beginning

of each interval.

Sessions were coded from videotapes using a computerized data

collection system. Interobserver agreement was calculated for child

problem behavior by breaking sessions into consecutive 10-s intervals

and dividing the smaller number of responses recorded by an observer

by the larger number of responses recorded by the other observer. The

resulting fractions were averaged across intervals and multiplied by

100%. Mean interobserver agreement for problem behavior was 93%

(range 87%-100%), 87% (range 79%-100%), 100%, and 88% (range

77%-100%) for Art, Don, Pat, and Tim, respectively. For partial inter-

val measures, percentages of occurrence and nonoccurrence agree-

ment were calculated by dividing the number of intervals in which

both observers agreed on the occurrence or nonoccurrence of the

response by the total number of intervals and multiplying by 100%.

Mean occurrence (OA) and nonoccurrence (NA) agreement scores for

therapist behaviors across participants are shown in Table 1.

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

360 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

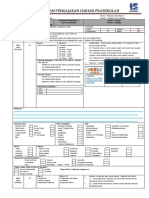

TABLE 1

Interobserver Agreement for Caregiver Responses and

Peer Responses; Total Agreement Scores Are Reported

% Art % Don % Pat % Tim

Caregiver Responses Agreement Agreement Agreement Agreement

Attention deprivation 99 98 99 95

Positive attention 94 96 99 99

Negative attention 97 93 98 96

Instructional context, present 100 100 100 100

Instructional context, absent 100 100 98 83

Physical prompt 100 100 100 100

Movement prompt 100 98 100 99

Nonmovement prompt 100 100 100 100

Tangible delivery 100 100 100 100

Tangible removal 100 100 98 100

Escape 100 96 100 99

Time-out — — — 90

Peer Responses

Positive attention 100 98 — 93

Negative attention 100 99 — 97

Interaction 100 86 — 94

PROCEDURE

Participants were exposed repeatedly to three or four conditions

similar to those described by Anderson and Long (2002): attention,

play, tangible, and task. For Don and Tim, sessions were conducted at

times of the day when activities related to a specific condition were

likely to occur. For example, task conditions were conducted when

activities such as cleanup or circle time occurred. Because there was

no set schedule in Art’s or Pat’s home, conditions were conducted in

random order. All sessions were 10 min in length and were videotaped

for later coding. Sessions were conducted until response differentia-

tion occurred. Definitions for preferred stimuli were obtained through

parental interviews and direct observation conducted prior to begin-

ning the study. Preferred stimuli for each participant were as follows:

Art, video games and television; Don, blocks; Pat, chalk and playing

outside; and Tim, riding toys (e.g., a tricycle).

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 361

Prior to conducting the study, caregivers were provided with a

rationale for the assessment and written instructions as to how to con-

duct each condition. Before each session, therapists were given spe-

cific instructions about the relevant antecedent variable being manip-

ulated and were asked to respond to problem behavior as they

typically would. Because antecedent conditions were controlled as

part of the assessment, therapists were asked to reestablish antecedent

events if the designated event had not occurred for 30 s in the absence

of problem behavior.

The purpose of the attention condition was to establish the anteced-

ent of attention deprivation. This condition was conducted during

times when the caregiver typically did not directly interact with the

child (e.g., was working with another child). Approximately 2 min

prior to the session, the caregiver was asked to play with the child.

When the session began, caregivers were told, “Pretend this is a time

that you cannot directly interact with the child. You may interact with

other children or engage in another activity, such as working at your

desk.” Caregivers also were asked to keep preferred tangibles out of

sight and reach of the child. The play condition was designed to simu-

late an enriched environment, similar to the play condition of the ana-

log functional analysis. Preferred items were available and caregivers

were told, “In this role-play, we would like to see how the child

responds when you are not making requests and preferred items are

available. Please play with the child as you normally do.” The purpose

of the tangible condition was to establish the antecedent of removal of

preferred tangibles. This condition was conducted when access to pre-

ferred items was ending (access had occurred for at least 2 min). At the

beginning of the condition, caregivers were told, “In this role-play we

want to see how the child reacts when preferred activities end. When

we tell you to begin, please remove [preferred item]. You may interact

with the child as you desire, but please refrain from attempting to

engage the child in work activities.” Although the tangible condition

was initially conducted with Don and Tim, it was discontinued

because tangible removal almost always immediately preceded tran-

sition to work activities (e.g., table work, cleanup, circle time), and,

due to the structure of the day care situation, caregivers were unable to

refrain from engaging the child in the work activity. Thus, the tangible

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

362 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

condition was equivalent to the task condition and was discontinued

(data from early tangible conditions are available from the first author

on request). The task condition, designed to establish the antecedent

of presentation of requests to work, was conducted when the partici-

pant was expected to complete tasks. For Art and Pat, tasks consisted

primarily of picking up toys. Tasks for Don and Tim included circle

time, cleanup, and table activities (e.g., art). Removal of preferred tan-

gibles or activities did not occur within 2 min of initiating this condi-

tion. At the start of the task condition, caregivers were told, “In this

role-play we want to see how the child responds to requests. Please

work with the child on activities that you typically engage the child in,

and use prompting strategies you normally use.”

DATA ANALYSIS

Mean responses per minute of problem behavior were compared

across conditions of the SDA. In addition, conditional probabilities

were calculated to evaluate the relation between environmental events

(caregiver and peer responses) and child problem behavior. To calcu-

late proportions, the first occurrence of child problem behavior in an

interval was used (as if it was coded as a partial interval measure).

Conditional probabilities were calculated for environmental events

that occurred within 5 s of a response. Two kinds of conditional proba-

bilities were conducted. First, event-based proportions were calcu-

lated by dividing intervals in which an environmental event preceded

(e.g., physical prompt) or followed (e.g., negative attention) problem

behavior by 5 s or less by the total number of intervals scored with the

event. In the case of antecedent events, event-based proportions reveal

the proportion of intervals scored with an event that preceded problem

behavior. In the case of consequent events, event-based proportions re-

veal the proportion of events that were response dependent. Behavior-

based proportions were calculated by dividing intervals in which an

environmental event preceded or followed problem behavior by 5 s or

less by the total number of intervals scored with the problem behavior.

When calculated for antecedent events, behavior-based proportions

reveal the proportion of intervals scored with problem behavior pre-

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 363

ceded by an event. When calculated for consequent events, these pro-

portions speak to the putative schedule of reinforcement; the closer

the proportion is to 1 the denser the schedule of reinforcement.

Conditional probabilities were calculated across sessions and also

in the presence of relevant antecedent stimuli. For example, attention

delivery was calculated as a consequence across the entire session and

also only in the presence of antecedent events that might function as

establishing operations (e.g., attention deprivation). Event-behavior

relations were calculated in the presence of the following antecedents:

attention delivery as a consequence in the presence of attention depri-

vation, tangible deprivation, and prompts; escape in the presence of

prompts; tangible delivery in the presence of tangible removal; and

peer attention in the presence of adult attention deprivation. For all

environment-behavior relations, proportions calculated within the

presence of relevant antecedent variables were more revealing, so

only those calculations are reported (the remaining proportions are

available from the first author).

RESULTS

Figures 1 to 4 depict mean levels of problem behavior across condi-

tions of the SDA (top panels) and results of the conditional probability

calculations from the SDA for each participant. The mean percentage

of session time that antecedent variables were scored in each condi-

tion of the SDA is shown in Table 2. Calculations were obtained by

dividing the number of intervals in which an antecedent stimulus was

scored by the total number of intervals.

Art. Art exhibited the highest rates of problem behavior in the

attention condition of the SDA. Conditional probabilities revealed

that problem behavior never occurred in the presence of prompting in

any condition and that the only consequences that followed problem

behavior were adult and peer attention (in the presence of adult atten-

tion deprivation). Thus, further analyses were conducted on adult and

peer attention. The middle and bottom panels of Figure 1 depict event-

based (middle panel) and behavior-based (bottom panel) conditional

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

364 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

Figure 1. Mean responses per minute of problem behavior across conditions of the SDA

(structured descriptive assessment) for Art (top panel); proportion of event

intervals following problem behavior (middle); and proportion of problem

behavior intervals preceding events (bottom panel) during the SDA.

probabilities for adult and peer attention delivery in the presence of

adult attention deprivation. The focus is on the attention condition, as

problem behavior rarely occurred in other conditions. In the attention

condition, the event-based proportions reveal that although adult posi-

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 365

tive attention was more likely to occur independent of problem behav-

ior, the majority of intervals (62%) scored with negative attention fol-

lowed problem behavior (middle panel). Interestingly, although peer

attention was only slightly more likely to follow problem behavior

than to occur at other times, the only type of peer attention that ever

followed problem behavior was negative attention. Behavior-based

proportions reveal that problem behavior was followed by positive or

negative adult attention only intermittently and that one type of atten-

tion was not significantly more likely to follow problem behavior than

the other (bottom panel). Although adult attention was delivered con-

tingent on problem behavior on a rather thin schedule, the duration of

attention delivery was slightly longer following problem behavior;

attention delivery lasted an average of one interval when it occurred

response independently but lasted an average of two intervals when

attention followed problem behavior. As was the case with adult atten-

tion, peer attention, which was exclusively negative attention, fol-

lowed problem behavior on an intermittent schedule (although

negative peer attention followed problem behavior more often than

did adult attention).

Don. Don exhibited problem behavior in the task, attention, and

control conditions (top panel, Figure 2). In the presence of attention

deprivation (second panels), attention was much more likely to occur

independent of problem behavior (left panel), and problem behavior

was followed by attention only rarely (right panel). Peer attention

never followed problem behavior. In the presence of prompts (third

panels), attention also was more likely to occur at other times than

after problem behavior (third left panel), and only a small proportion

of intervals scored with problem behavior in the presence of prompts

were followed by attention (third right panel). In the presence of

prompts, escape was much more likely to be delivered contingent on

problem behavior than to occur at other times (76% of intervals scored

with escape in the task condition preceded problem behavior). Behavior-

based proportions reveal that just more than half of the intervals

scored with problem behavior were followed by escape. Not only was

escape more likely to follow problem behavior than to occur at other

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

366 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

Figure 2. Mean responses per minute of problem behavior across conditions of the SDA

(structured descriptive assessment) for Don (top panel); proportion of event

intervals following problem behavior in the presence of attention deprivation

(second left panel); proportion of problem behavior intervals preceding events

(second right panel) in the presence of attention deprivation; proportion of

event intervals following problem behavior in the presence of prompts (third left

panel); proportion of problem behavior intervals preceding events (third right

panel) in the presence of prompts; proportion of prompt intervals preceding

problem behavior (bottom left panel); and proportion of problem behavior

intervals following prompts (bottom right panel) during the SDA.

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 367

times, but the duration of escape was greater when it followed prob-

lem behavior as well. The mean duration of escape scored outside of

problem behavior was 17 s; mean duration of escape following prob-

lem behavior was 64.48 s. Follow-up analyses conducted in the task

condition revealed that prompts requiring physical movement were

most likely to evoke problem behavior (bottom left panel), and that of

all the intervals scored with problem behavior in the presence of

prompting, 88% of problem behavior intervals followed a prompt

requiring physical movement (bottom right panel).

Pat. Pat exhibited problem behavior primarily in the tangible con-

dition (top panel, Figure 3). Across conditions, problem behavior

occurred exclusively in the presence of attention deprivation or tangi-

ble removal, so further analyses were conducted in the presence of

these antecedent conditions. In the presence of attention deprivation,

although attention irrespective of type (positive or negative) was

slightly more likely to occur at times other than after problem behav-

ior, negative attention was delivered only following problem behav-

ior. Behavior-based proportions (middle right panel) reveal that prob-

lem behavior was followed exclusively by negative attention and that

negative attention followed problem behavior on a rich schedule (FR-1

in the attention condition). A similar pattern is seen in the presence of

tangible deprivation (bottom panels); the majority of intervals scored

with negative attention (all intervals in the control condition) followed

problem behavior (bottom left panel), and the majority of intervals

scored with problem behavior were followed by negative attention

(bottom right panel).

Tim. Tim exhibited high rates of problem behavior in all conditions,

and responding was relatively undifferentiated across conditions (top

panel, Figure 4). The second panels of Figure 4 show that during times

of attention deprivation, attention was rarely delivered independent of

problem behavior (left panel) and that the only type of attention to fol-

low problem behavior was negative attention. Behavior-based propor-

tions (second right panel) reveal that problem behavior was followed

by negative attention on an intermittent schedule across conditions.

Attention delivered independent of problem behavior lasted an aver-

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

368 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

Figure 3. Mean responses per minute of problem behavior across conditions of the SDA

(structured descriptive assessment) for Pat (top panel); proportion of event

intervals following problem behavior in the presence of attention deprivation

(middle left panel); proportion of problem behavior intervals preceding events

in the presence of attention deprivation (middle right panel); proportion of

event intervals following problem behavior in the presence of tangible depriva-

tion (bottom left panel); proportion of problem behavior intervals preceding

events (bottom right panel) in the presence of tangible deprivation during the

SDA.

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 369

Figure 4. Mean responses per minute of problem behavior across conditions of the SDA

(structured descriptive assessment) for Tim (top panel); proportion of event

intervals following problem behavior in the presence of attention deprivation

(second left panel); proportion of problem behavior intervals preceding events

in the presence of attention deprivation (second right panel); proportion of

event intervals following problem behavior in the presence of prompts (third left

panel); proportion of problem behavior intervals preceding events (third right

panel) in the presence of prompts; proportion of event intervals following prob-

lem behavior in the presence of time-out (bottom left panel); proportion of prob-

lem behavior intervals preceding events (bottom right panel) in the presence of

prompts during the SDA.

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

370 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

age of three intervals, and response-dependent attention lasted an

average of six intervals.

In the presence of prompts (third panels), attention was slightly

more likely to occur outside of problem behavior (with the exception

of prompts delivered in the attention condition), but, again, the major-

ity of attention delivered was negative attention and it followed prob-

lem behavior only intermittently. In the task condition, escape was

more likely to follow problem behavior than to occur at other times

(left panel), and 62% of intervals scored with problem behavior were

followed by escape. Proportions were slightly lower in other condi-

tions; however, prompts occurred only rarely in these conditions. Es-

capes occurring after problem behavior typically were longer than es-

capes occurring at other times; mean duration of escape after problem

behavior was 74 s, mean duration of escape at other times was 43 s.

Physical prompts and prompts requiring movement to complete were

most frequently associated with problem behavior: In the task condi-

tion, 67% of intervals scored with physical prompts and 39% of inter-

vals scored with prompts requiring movement preceded problem

behavior. Although 100% of intervals scored with escape in the pres-

ence of physical prompts followed problem behavior, escape was less

likely to be dependent on problem behavior in the presence of other

types of prompts (resulting in the lower behavior-based proportions

for escape).

In the presence of time-out (bottom panels), the majority of inter-

vals scored with attention and escape (defined as allowing Tim to

leave the time-out chair prior to being given verbal permission to

leave) followed problem behavior, and problem behavior was fol-

lowed by attention (negative) on a dense schedule. Escape followed

problem behavior more intermittently, typically occurring after Tim

hit an adult and then eloped from the time-out chair.

CONTROL OVER ANTECEDENT VARIABLES

Table 2 depicts the mean percentage of intervals scored with ante-

cedent events in each condition of the SDA. Overall, caregivers imple-

mented antecedent conditions in the SDA with a high degree of integ-

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 371

rity; that is, relevant establishing operations were in effect. In the

attention condition, therapists rarely issued instructional prompts or

manipulated preferred tangibles, and attention deprivation was in

effect for the majority of sessions. In the task condition, preferred tan-

gibles were never manipulated. Tasks were presented in the majority

of intervals for Art and Pat but occurred less often for Don and Tim,

for whom the results of the SDA suggested escape might maintain

problem behavior. The tangible condition was conducted only with

Art and Pat, and tangible deprivation was in effect for the majority of

intervals for both participants. During the tangible condition, care-

givers emitted prompts only infrequently. In the play condition, care-

givers rarely issued instructional prompts (with the exception of Pat’s

mother who issued prompts in 23% of intervals), and tangible depri-

vation did not occur. Attention deprivation occurred only infrequently

for all participants except Tim; Tim’s caregiver often had to be

prompted to interact with Tim, and she typically did so in a rather

perfunctory manner.

EXPERIMENT 2: INTERVENTION

METHOD

Participants and Setting

Art and Don participated in Experiment 2. Pat did not participate

because parental custody was terminated shortly after completion of

the SDA (for reasons unrelated to her challenging behavior). Tim did

not participate because he was expelled from day care during the 2nd

day of intervention for bringing a pocketknife to day care. Art’s father

implemented intervention for Art, and Don’s day care instructors

implemented intervention for Don.

Response Measurement and Interobserver Agreement

Response definitions for problem behaviors were identical to those

in Experiment 1. Sessions were 10 min and were conducted two to six

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

372 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

TABLE 2

Mean Percentage of Intervals Containing Antecedent Events

Across Conditions of the Structured Descriptive Assessment

and Analog Functional Analysis

Condition Antecedent % Art % Don % Pat % Tim

Attention Attention deprivation 80 92 79 66

Prompt 4 0 2 2

Tangible deprivation 0 0 0.02 0

Peer interaction 24 47 NA 19

Task Attention deprivation 11 48 24 36

Prompt 58 26 59 30

Tangible deprivation 0 0 0 0

Peer interaction 6 21 NA 17

Tangible Attention deprivation 32 NA 52 NA

Prompt 4 NA 3 NA

Tangible deprivation 100 NA 99 NA

Peer interaction 0.01 NA NA NA

Control Attention deprivation 25 34 26 61

Prompt 0.01 2 23 3

Tangible deprivation 0 0 0 0

Peer interaction 23 43 NA 44

NOTE: Tangible deprivation was scored only if child previously had access to tangible item.

Thus, tangible deprivation is 0 in the task condition because the child never had access to the item

to have it removed.

times per day, two to four times per week. Observers used frequency

recording to collect data during sessions. Interobserver agreement

was assessed on child responses during at least 30% of all sessions.

Agreement coefficients were calculated as in Experiment 1. Mean

percentage agreement across baseline and treatment for child

responses was 93% (range 98%-100%) for Art and 88% (range 81%-

92%) for Don.

PROCEDURE

For both participants, intervention was matched to the function(s)

of problem behavior as identified via the SDA. An ABAB design was

used to evaluate the effects of the intervention for Art. An ABAB

design was planned for Don (and initially agreed on by the day care),

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 373

but his day care instructors were unwilling to remove the intervention

once it was in place.

Art. Data were collected during times Art’s father was involved

with other activities (the attention-deprivation condition of the SDA).

Art’s brother was present throughout the treatment evaluation. During

baseline, Art’s father was instructed to interact with Art as he nor-

mally did; however, if he interacted with Art for more than 1 min in the

absence of problem behavior, he was asked to return to what he previ-

ously had been engaged with. Intervention consisted of a 30-s chair

time-out contingent on problem behavior. Art’s father was taught to

tell Art, “No ____, go to time-out” and, if Art did not independently sit

in the time-out chair within 5 s, to physically guide him to time-out.

Art’s father was taught to hold Art in the chair if he attempted to elope,

but this occurred only during the initial time-out. Importantly, Art’s

brother was taught to ignore Art during time-out.

Don. Intervention for Don was conducted during times Don was

required to engage in tasks requiring physical movement, such as

cleaning up toys. During baseline, his teacher was asked to attempt to

have Don engage in the task and to respond to problem behavior as she

typically did. If she ceased prompting for 2 min in the absence of com-

pliance or problem behavior, she was asked to resume prompting.

Intervention consisted of differential reinforcement of compliance

with verbal praise and contingent physical guidance following

exhibition of problem behavior.

RESULTS

Results obtained for each participant are shown in Figure 5. In

baseline, Art emitted an average of 2.6 problem behaviors per minute

(see top panel). Intervention resulted in significant decreases in prob-

lem behavior, and a reversal to baseline conditions was implemented

to assess functional control. During the return to baseline conditions,

Art’s father was instructed to respond to problem behavior as he had

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

374 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

Figure 5. Mean responses per minute of problem behavior during the intervention analy-

ses for Art (top panel) and Don (bottom panel).

during baseline. Following reimplementation of time-out, rates of

problem behavior were completely suppressed.

Don emitted an average of 4.1 problem behaviors per minute in

baseline (bottom panel). Intervention with Don resulted in slightly

more than a 95% reduction over baseline.

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 375

DISCUSSION

The results of the current study extend previous work on functional

assessment. The SDA (Anderson & Long, 2002) was used with four

typically developing children and was found to be useful in develop-

ing hypotheses about environment-behavior relations.

For all children, it was necessary to examine conditional probabili-

ties in addition to overall response rates to develop hypotheses about

functional relations. For example, Art exhibited the highest rates of

responding in the attention condition (suggesting adult attention

might maintain problem behavior), but peer attention as well as adult

attention were suggested by conditional probabilities to maintain

problem behavior (note that peer attention as a putative reinforcer can

be identified only via conditional probabilities). Don exhibited ele-

vated rates of responding across conditions; however, the conditional

probabilities suggested that problem behavior was related almost

exclusively to task presentation and maintained primarily by escape

or avoidance. Conditional probabilities also were useful for providing

more specific information about environmental events such as the

type of task most likely to evoke problem behavior or the type of

attention (positive or negative) likely maintaining behavior.

The SDA may be a useful method for conducting descriptive

assessments because structuring the antecedent conditions increases

the likelihood that problem behavior will occur yet still allows for

observation of naturally occurring consequences and schedules of

reinforcement. For example, peer attention, a variable not typically

assessed in experimental functional assessments, was suggested to

maintain Art’s problem behavior. Also, contingent delivery of pre-

ferred tangibles, a consequence frequently assessed for in experimen-

tal functional analyses, never occurred contingent on problem

behavior in the current study.

There were a number of limitations in the current study that warrant

further investigation. First, there was some carryover of antecedent

events across conditions in the current study, something that rarely

occurred in Anderson and Long (2002). Interestingly, this was much

more likely to occur with Don and Tim, whose SDAs were conducted

in day care. Anecdotal evidence suggests that this may have occurred

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

376 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

because the day was highly structured and prompts (as defined in the

current study) frequently occurred. For example, during free play,

adults often attempted to structure the situation or facilitate learning

by asking children to label objects or complete other such requests.

One solution to this might be to more rigidly define “task.” Another

possible solution, and one that might result in greater stability across

sessions, would be to run SDA conditions until problem behavior is

observed and to then conduct conditional probabilities on antecedent

events to identify the specific type of antecedent (e.g., movement

prompts vs. nonmovement prompts; attention deprivation during

which the adult was working with another child vs. sitting at a desk)

related to problem behavior and to then manipulate that antecedent

variable systematically.

Perhaps the greatest limitation of the current study is that hypothe-

sized functional relations were not evaluated experimentally.

Although interventions were developed based on the results of the

SDA for 2 participants, the extent to which the SDA resulted in accu-

rate hypotheses about functional relations cannot be determined.

Future research should focus on experimentally manipulating envi-

ronmental events suggested by the SDA to be related to problem

behavior and evaluate the utility of interventions derived from the

SDA with more participants.

Future research also should examine the extent to which participa-

tion in a functional assessment affects caregivers’ understanding of

functional relations and the likelihood they will accurately implement

a functionally derived intervention. In the current study, interviews

conducted prior to conducting the functional assessments suggested

that caregivers had little understanding of the relation between envi-

ronmental events and their child’s problem behavior. Results of the

SDA were shared with caregivers following the assessment and all,

with the exception of Pat’s mother, reported understanding the rela-

tion between their own behavior and the behavior of the target child.

Unfortunately, the effects of participating in a functional assessment

on caregiver understanding of environment-behavior relations were

not directly assessed in this study; this is an important direction for

future research.

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

Anderson et al. / STRUCTURED DESCRIPTIVE ASSESSMENT 377

NOTE

1. All names used in this article are pseudonyms.

REFERENCES

Anderson, C. M., Freeman, K. A., & Scotti, J. R. (1999). Evaluation of the generalizability (reli-

ability and validity) of analog functional assessment methodology. Behavior Therapy, 30,

31-50.

Anderson, C. M., & Long, E. (2002). Evaluation of structured functional assessment methodol-

ogy. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 35, 137-154.

Broussard, C. D., & Northup, J. (1995). The use of functional analysis to develop peer interven-

tions for disruptive classroom behavior. School Psychology Quarterly, 12, 65-76.

Carr, E. G. (1994). Emerging themes in the functional analysis of problem behavior. Journal of

Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 393-399.

Carr, E. G., Yarbrough, S. C., & Langdon, N. A. (1997). Effects of idiosyncratic stimulus vari-

ables on functional analysis outcomes. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 30, 673-686.

Dunlap, G., Kern, L., dePerczel, M., Clarke, S., Wilson, D., Childs, K. E., et al. (1993). Func-

tional analysis of classroom variables for students with emotional and behavioral disorders.

Behavioral Disorders, 18, 275-291.

Ervin, R. A., Kern, L., Clarke, S., DuPaul, G. J., Dunlap, G., & Friman, P. C. (2000). Evaluating

assessment-based intervention strategies for students with ADHD and comorbid disorders

within the natural classroom context. Behavioral Disorders, 25, 344-358.

Fox, J., Conroy, M., & Heckaman, K. (1998). Research issues in functional assessment of the

challenging behaviors of students with emotional and behavioral disorders. Behavioral Dis-

orders, 24, 26-33.

Freeman, K. A., Anderson, C. M., & Scotti, J. R. (2000). A structured descriptive methodology:

Increasing agreement between descriptive and experimental analyses. Education and Train-

ing in Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities, 35, 55-66.

Hanley, G. P., Iwata, B. A., & McCord, B. E. (2003). Functional analysis of problem behavior: A

review. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 36, 147-185.

Harding, J., Wacker, D. P., Cooper, L. J., Asmus, J., Jensen-Kovalan, P., & Grisolano, L. (1999).

Combining descriptive and experimental analyses of young children with behavior problems

in preschool settings. Behavior Modification, 23, 314-333.

Heckaman, K., Conroy, M., Fox, J., & Chait, A. (2000). Functional assessment-based interven-

tion research on students with or at risk for emotional and behavioral disorders in school set-

tings. Behavioral Disorders, 25, 196-210.

Iwata, B. A., Dorsey, M. F., Slifer, K. J., Bauman, K. E., & Richman, G. S. (1994). Toward a func-

tional analysis of self-injury. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis, 27, 197-209.

Lewis, T. J., & Sugai, G. (1996). Functional assessment of problem behavior: A pilot investiga-

tion of the comparative and interactive effects of teacher and peer social attention on students

in general education settings. School Psychology Quarterly, 11, 1-19.

Mace, F. C., Lalli, J. S., Pinter Lalli, E., & Shea, M. C. (1993). Functional analysis and treatment

of aberrant behavior. In R. Van Houten & S. Axelrod (Eds.), Behavior analysis and treatment

(pp. 102-125). New York: Plenum.

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

378 BEHAVIOR MODIFICATION / May 2006

Sasso, G. M., Conroy, M. A., Stichter, J. P., & Fox, J. J. (2001). Slowing down the bandwagon:

The misapplication of functional assessment for students with emotional or behavioral disor-

ders. Behavioral Disorders, 26, 282-296.

Umbreit, J. (1995). Functional assessment and intervention in a regular education classroom for

the disruptive behavior of a student with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Behavioral

Disorders, 20, 267-278.

Cynthia M. Anderson, Ph.D., is an assistant professor in the Department of Psychology

at West Virginia University. Her research interests include evaluating the generality and

utility of methods of functional assessment across populations and settings.

Carie L. English, Ph.D., is a visiting professor at the University of South Florida. Her

research interests include technology transfer and the assessment and treatment of

severe problem behavior.

Theresa M. Hedrick is a graduate student in the behavior analysis program at West Vir-

ginia University. Her research interests include evaluating methods of functional assess-

ment and functionally derived interventions.

Downloaded from bmo.sagepub.com at UNIV OF NEVADA RENO on December 2, 2014

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Dark Ages Vampire Editable Character Sheet 4 PagesDocument4 pagesDark Ages Vampire Editable Character Sheet 4 PagesGarrett Adams100% (2)

- Your Next Five MovesDocument11 pagesYour Next Five MovesSESR136% (11)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Grace Ptak - Ap Research Proposal Form Fa20Document2 pagesGrace Ptak - Ap Research Proposal Form Fa20api-535713278No ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Venus in Taurus in 12th HouseDocument2 pagesVenus in Taurus in 12th HouseCatalina Georgiana Moraru0% (1)

- Trans Cultural Human ValueDocument8 pagesTrans Cultural Human ValueFaizal Faizu100% (2)

- MIE Presentation TemplateDocument11 pagesMIE Presentation TemplateSendriFebriyansyahNo ratings yet

- Adolescent Substance AbuseDocument47 pagesAdolescent Substance AbuseIssa Thea BolanteNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument2 pagesEssayConsti-InqNo ratings yet

- Decision Matrix - Selection GridDocument4 pagesDecision Matrix - Selection GridSmriti ShahNo ratings yet

- Reading: Test 1Document10 pagesReading: Test 131郭譿斳VeraNo ratings yet

- 300 Gre Words With Their MeaningsDocument12 pages300 Gre Words With Their MeaningsBeatking HarshilNo ratings yet

- RPH Perayaan Hari RayaDocument18 pagesRPH Perayaan Hari RayaMammi TwinNo ratings yet

- WeaveTech SolutionDocument3 pagesWeaveTech Solutionjennifer aj100% (1)

- Self KnowledgeDocument34 pagesSelf KnowledgeASh tabaogNo ratings yet

- Polygraph Tests - Benefits and ChallengesDocument10 pagesPolygraph Tests - Benefits and ChallengesahmedNo ratings yet

- Rony-Case FinalDocument72 pagesRony-Case FinalTasnim AlomNo ratings yet

- Creating CaptionsDocument5 pagesCreating CaptionsMas RizalNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson PlanDocument3 pagesDetailed Lesson PlanJolo MercadoNo ratings yet

- Perception of Pupil Teachers' Regarding Micro Teaching SessionsDocument3 pagesPerception of Pupil Teachers' Regarding Micro Teaching SessionsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Busa 331 Chapter 14Document18 pagesBusa 331 Chapter 14Mais MarieNo ratings yet

- 1413 SATDT ReportDocument14 pages1413 SATDT ReportgriheetNo ratings yet

- Principles of Handling ObjectionDocument16 pagesPrinciples of Handling ObjectionFrancis Rey Gayanilo100% (1)

- Measures of Variability: Prof. Michelle M. Mag-IsaDocument46 pagesMeasures of Variability: Prof. Michelle M. Mag-IsaMichelle MalabananNo ratings yet

- MODULE 6 - Week 2 - The Child and Adolescent Learners and Learning PrinciplesDocument7 pagesMODULE 6 - Week 2 - The Child and Adolescent Learners and Learning PrinciplesMarsha MGNo ratings yet

- Horror FilmsDocument3 pagesHorror FilmsJonathanNo ratings yet

- Compassion Fatigue Keynote SpeakerDocument2 pagesCompassion Fatigue Keynote SpeakerBarbara RubelNo ratings yet

- Psychological MCQsDocument4 pagesPsychological MCQsDashMadNo ratings yet

- Learning Task 1:: Objective Relevance ConcisenessDocument2 pagesLearning Task 1:: Objective Relevance ConcisenessTavera Jericho De LunaNo ratings yet

- General Myp4-5 Reporting Rubric CDocument4 pagesGeneral Myp4-5 Reporting Rubric Capi-244457674No ratings yet

- Guftargoo Written by Ayaat AttarDocument14 pagesGuftargoo Written by Ayaat AttarAyaat AttarNo ratings yet