Professional Documents

Culture Documents

The Johns Hopkins University Press

Uploaded by

Francisca Monsalve C.Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

The Johns Hopkins University Press

Uploaded by

Francisca Monsalve C.Copyright:

Available Formats

Packing History, Count(er)ing Generations

Author(s): Elizabeth Freeman

Source: New Literary History, Vol. 31, No. 4, Is There Life after Identity Politics? (Autumn,

2000), pp. 727-744

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/20057633 .

Accessed: 09/08/2013 10:10

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to

New Literary History.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

Packing History, Count (er) ing Generations

Elizabeth Freeman*

"Do you identify up, or down?"

Anonymous, in personal conversation, circa 1992

As A graduate student teaching my first solo course in Lesbian

and Cay Studies in 1993, at a moment when "identity" was

rapidly morphing into cross-gender identification, I told an

anecdote I thought would illustrate this crossing: "Iwear this T-shirt that

says 'Big Fag' sometimes, because lesbians give potlucks and dykes fix

cars. I've never done well at either, so feels more

'Big Fag' appropriate."

A student came to see me

hours, quite upset. She was in her

in office

early twenties, a few years younger than I, but she dressed like my

feminist teachers had in college. She stood before me in Birkenstocks,

wool socks, and a women's music T-shirt, and declared that she felt

jeans,

dismissed and my comment, that

marginalized by lesbians-who-give

potlucks her exactly, and that I had clearly fashioned

described a more

own as a

interesting identity with her foil. I had thought I was telling a

story about being inadequate to prevailing lesbian identity-forms, or

about allying with gay men, or perhaps even about the lack of represen

tational choices for signaling femme. But it turned out that Iwas telling a

story about anachronism, with "lesbian" as the sign of times gone by and

her body as an implicit teaching text.

Momentarily displaced into my own history of feeling chastised by

feminisms that preceded me, yet aware that this student had felt

disciplined by my joke in much the same way, I and a

apologized, long

conversation about identification between students and teachers followed.

But what interests me now is the that student's

way self-presentation

*A Mellon at the University of Pennsylvania's Penn Humanities

postdoctoral fellowship

Forum gave me much-needed time to produce this essay. Many thanks to Heather Love,

Molly McGarry, Ann Pellegrini, and Elizabeth Subrin for their help along the way. For

stern early interventions I thank the Faculty Working in Queer at New York

Group Theory

University, especially Douglas Crimp, Ann Cvetkovich, and Patty White. Any remaining

errors or misfires, of course, I claim as my own.

conceptual

New Literary History, 2000, 31: 727-744

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

728 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

ruptured any easy assumptions about lesbian generations and registered

the failure of the "generational" model to capture political differences

between two women who had race, class, and sexual

nationality, prefer

ence in common. The

incongruity of her body suggested that

temporal

she simply did not identify with what I would have taken to be her own

emergent peer culture of neopunk polymorphs, Queer Nationals, Riot

Grrrls, and so on?nor with culture of neo-butch/femme, consumer

my

ist sex radicalism. Her then, was different than the

body's "crossing,"

gender crossings that queer studies was just beginning to privilege. It was

a of time, less in the mode of than in the

crossing postmodern pastiche

mode of stubborn identification with a set of social coordinates that

exceeded her own historical moment.

Let us call this "temporal drag," with all of the associations that the

word "drag" has with retrogression, delay, and the pull of the past upon

the present. This kind of drag, as opposed to the queenier kind

celebrated in queer cultural studies, suggests the gravitational pull that

"lesbian" sometimes seems to exert In many discussions of

upon "queer."

the relationship between the two, it often seems as if the lesbian feminist

is cast as the big drag, drawing politics inexorably back to essentialized

bodies, normative visions of women's and

sexuality, single-issue identity

politics. Yet for those of us for whom queer politics and theory involve

not disavowing our relationship to particular (feminist) histories even as

we move away from identity politics, thinking of "drag" as a temporal

also raises a crucial what is the time of

phenomenon question: queer

performativity?

In formulating her landmark theory of queer performativity, Judith

Butler's answer to this question seems to be that its time is basically

progressive, insofar as it depends upon repetitions with a difference?

iterations that are transformative and future-oriented. In Gender Trouble,

an such as "lesbian" is most promising for the unpredict

identity-sign

able ways it may be taken up later. Repetitions with any backwards

force, on the other hand, are "citational," and carl

looking merely only

thereby consolidate the authority of a fantasized original. The time of

masculine and feminine is even more retroac

ordinary performativity

tive: the "original" sexed body that seems to guarantee the gendered

is in fact a back-formation, a

subject's authenticity hologram projected

onto earlier moments. The political result of these temporal formula

tions can be that whatever looks newer or more-radical-than-thou has

more purchase over prior signs, and that whatever seems to generate

continuity seems better left behind. But to reduce all embodied perform

ances to the status of copies without originals is to ignore the interesting

threat that the genuine past-ness of the past sometimes makes to the

political present. And as other critics have pointed out, the theoretical

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PACKING HISTORY, COUNT(er)iNG GENERATIONS 729

work of "queer performativity" sometimes (though not always) under

mines not just the essentialized body that haunts lesbian and gay identity

politics, but political history?the expending of actual physical energy in

less spectacular or theatrical forms of activist labor done in response to

historically specific crises.1

Though "temporal drag" is always a constitutive part of subjectivity,

exteriorized as a mode of embodiment it may also offer a way of

connecting queer performativity to disavowed political histories. Might

some bodies, in registering on their very surfaces the co-presence of

several events, movements, and collective

historically-specific pleasures,

or displace the centrality

of gender-transitive

complicate drag to queer

instead a

they articulate

kind of

performativity? Might temporal transitiv

ity that does not leave feminism, femininity, or other "anachronisms"

behind? I ask this not to dismiss Butler's work?which has facilitated all

kinds of promising Cultural Studies projects that depend upon the

decoupling of identities and practices?but rather to use her to think

specifically about the history of feminism, bringing out a temporal

aspect that I think is often overlooked in descriptions of her important

turn from performativity to what she calls the psychic life of power. As I

will go on to argue, Butler does indeed provide a way of

thinking about

across time, of as a obstacle to

identity relationally "drag" productive

progress, a usefully distorting pull backwards, and a necessary pressure

upon the present tense. But the form of drag I would like to extrapolate

from her work moves beyond the parent-child relation that has struc

tured and therefore transform a

psychoanalysis, might usefully "genera

tional" model of politics. For though some feminists have advocated

abandoning the generational model because it relies on family as its

dominant metaphor and identity as the it passes on,2 the

commodity

concept of generations linked by political work or even by mass

entertainment also acknowledges the ability of various culture industries

to produce shared subjectivities that go beyond the family. "Genera

tion," a word for both biological and forms of replication,

technological

cannot be tossed out with the bathwater of reproductive thinking.

Instead, itmay be crucial to complicate the idea of horizontal political

one another, with a notion of

generations succeeding "temporal drag,"

thought less in the psychic time of the individual than in the movement

time of collective political life.

Recently, I encountered a video artist's recent meditation on radical

feminism in which this project seems central: in Elisabeth Subrin's short

experimental video Shulie (1997), a queer vision of embodiment inter

sects with some feminist concerns about and

generationality, continuity,

historicity. Some background: Shulie is a shot-by-shot remake of an

unreleased 1967 documentary film with the same title. The earlier Shulie

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

730 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

examined a then-unknown student at the Art Insti

twenty-two-year-old

tute of Chicago named Shulamith Firestone, who went on shortly after

the documentary's completion to organize the New York Radical Women

in 1967, the Redstockings in early 1969, and the New York Radical

Feminists in the fall of 1969, and eventually to write the groundbreaking

feminist manifesto The Dialectic of Sex in 1970.3 Rather than reworking

Shulie (1967) into a documentary that links the postadolescent art

student with the pioneering radical feminist she became, Subrin re

staged the original film

and meticulously duplicated its camerawork,

adding a montage

sequence at the beginning and framing the piece

with several explanatory texts. We learn that in 1967, four male Chicago

art students were commissioned to portray the "Now Generation" of the

late 1960s, among them Firestone. The title card reads "Shulie, ?1967,"

as ifwhat we are about to see is the original film. But the 1997 video ends

with a text explaining that it is an adaption of the 1967 film and

crediting its makers, then announcing that Firestone moved to New

York shortly after the filming to found the radical feminist movement

and write The Dialectic of Sex.4 The final framing text puts Firestone into

a feminist genealogy, claiming that her ideas about cybernetic reproduc

tion anticipated many postmodernist analyses of the relationship be

tween technology and gender. Shulie (1997) also honors the way

Firestone herself paid homage to her predecessors: The Dialectic of Sex is

"for Simone de Beauvoir, who endured"; after Subrin's credits comes a

dedication "for Shulamith Firestone, who has endured," more

perhaps

in the feminist unconscious than on Women's

contemporary political

Studies syllabi. Indeed, despite this evocation of a feminist legacy, Shulie

(1997) consistently undermines the idea that an intact feminist world

has been handed down from older women to ones. Further

younger

complicating its work as a feminist historical document, the video is also

infused with the vicariousness and self-conscious theatricality that have

become the hallmarks of queer cultural texts.

The montage sequence of the 1997 Shulie opens with a sign that

condenses the eroticism of recent revivals of

lesbian-queer gender play,

and the historicism that is an often unacknowledged but constitutive

part of queer performance. Subrin's first shot, lasting twenty-four

seconds, shows a set of empty train tracks leading into downtown

a part of the skyline in the background. In the foreground, we

Chicago,

see a shabby warehouse?itself an index of industrial capitalism now

often located rhetorically in the nation's past. The side of this warehouse

reads "New Packing Co." This sign acknowledges that the video itself is

a reshoot, and alludes to the repackaging of collective feminist activism

into individual, consumerist style in the 1980s and beyond. Yet in the

context of a video about Second Wave feminism, the phrase also

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PACKING HISTORY, COUNT(ER)lNG GENERATIONS 731

momentarily reminds at least some audience members of the central

role that "packing"?the wearing of dildos?had as radical separatist

feminism metamorphosized into the sex wars of the 1980s. Finally, the

warehouse is the sign of an ellipse: Subrin has reshot a film that was

sign

never released because Shulamith Firestone asked its makers never to

show it.5 What the audience can see, instead, is a

contemporary repack

aging of feminist history's outtakes, which turns out to pack a punch.

This convergence of a decrepit icon of manual labor and a phrase that

eroticism, and consumer the

suggests style, pleasures, prefigures way

that Subrin's remake

eventually the post-feminist "now" of its

disorients

own moment. As the camera lingers on the "New Packing" sign,

fragments of sound fade in: the clacking of train wheels, chants of "2, 4,

6, 8," a staticky broadcast of a black male voice declaring, "thousands of

young people are being beaten in the streets of Chicago" as the camera

moves away from the sign, revealing a recognizably 1990s Chicago whose

streets look

empty. While the image track accumulates shots of still

buildings, deserted streets, and hollow underpasses shot in the present,

the soundtrack spills forth more political detritus from the late 1960s:

them, a male voice demands, "Am I under arrest? Am I under

among

arrest?," a crowd chants "Peace now," a tenor "Miss

warbling sings

America." Over this, sirens from the sound an alarm that seems

past

aimed directly at the current moment. The title card marks the

beginning of the video's diegetic time and of its cinematographic

merger with the prior film. Yet the first words of its interviewee, Shulie,

undermine the soundtrack's prior suggestion that the Chicago of the

1960s may be a lost political utopia: "I don't like Chicago," Shulie

begins, and anyone who has lived there understands the combination of

hope and pessimism that she says the city inspires in her.

In fact, for Shulie, 1967 seems just as politically empty as the video's

presentation of 1997. Within the diegetic boundaries of the video that

follows the montage, even though the camerawork and action exactly

follow the 1967 original, we see little evidence of the earlier period's

activism. Instead of a documentary history of radical feminism, a biopic

of Firestone's entire life, or an of feminisms "now"

explicit comparison

and "then," Subrin delivers a series of observations and

throwaway

incidents in the life of a depressive, very smart young Jewish female in

her final year at the Art Institute. Listening to Shulie's commentary,

which is startlingly ? propos to our own moment, audience members are

forced to confront the fact that the prehistory of radical feminism is very

much like its aftermath, that we have a certain postmodern problem that

no has a name?or rather, whose names are under

longer increasing

erasure. And Shulie is clearly a figure for Subrin; the videomaker herself

is also a very smart, middle-class Jewish female artist whose prior work is

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

732 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

about depression, and who had just graduated from the Art Institute

when she as neither monument nor

began shooting.6 History reappears

farce, but as the of a ("so moans

angelface twenty-two-year-old young!"

one of Shulie's

teachers), a promise not yet redeemed for the

thirtysomething videomaker, thirty years later.

Of course this video is completely different from a drag performance.

If anything, the purportedly humorless radical feminist is the political

subject-position that has seemed most at odds with the drag queen. But

in its chronotopic disjunctiveness, Subrin's work does partake in a

temporal economy to queer performance

crucial and harnesses it to

movements the shimmyings

that go beyond of individual bodies and to

the problematic relationship between feminist history and queer theory.

Moving from an opening landscape that features the evacuated ware

houses of 1990s post-industrial Chicago to follow Shulie through the

junkyards she photographed in the 1960s, and ultimately toward the

question of what Second Wave feminism might mean to those who did

not live through it except possibly as children, the video partakes in the

love of failure, the rescue of that constitutes the most angst

ephemera,

ridden side of queer camp performance. As Andrew Ross and Richard

Dyer have argued, the camp effect depends not just upon inverting

binaries such as male/female, high/low, and so on, but also upon

resuscitation of the obsolete cultural text.7 This multitemporal aspect of

seems to inform Subrin's use of what she elsewhere calls Shulie's

camp

"minor, flawed, and non-heroic" at the Art Institute and even

experience

the video's willingness to redeploy radical feminism and yet as a failed

also incomplete political project.8

Shulie's investment in cultural castoffs and potentially embarrassing

resonates also with a crucial turn in Butler's work: not the

prehistories

turn from theatricality to material bodies that marks the movement

from Gender Trouble to Bodies That Matter, but the shift from a non

narrative, futuristic model of "iteration" to a narrative, historicist model

of "allegorization," in which the material by-products of past failures

write the poetry of a different future. As Butler suggests at the end of

"Imitation and Gender Insubordination" and amplifies in The Psychic Life

of Power, normative gender identity may itself be melancholic, emerging

when a is forced to renounce her desire for her same-sex

subject parent

and then

compensates by assuming

as her own body the one she has

been forced to give up wanting sexually.9 Preserving the lost object of

desire in the form of a gendered subjectivity, the

improper properly

man or woman is, as Butler eloquently puts it, "the

manly womanly

remainder . .. of unresolved (PL 133). She goes on

archaeological grief

to suggest that drag performance "allegorizes heterosexual melancholy, the

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PACKING HISTORY, COUNT (ER)ING GENERATIONS 733

melancholy by which a masculine, gender is formed from the refusal to

the masculine as a possibility of love; a feminine gender is formed

grieve

(taken on, assumed) through the incorporative fantasy by which the

feminine is excluded as a possible object of love, an exclusion never

grieved, but 'preserved' through heightened feminine identification"

(PL 146). In this revision of the Oedipus complex, the lover's gendered

identity takes shape not only through the melancholic preservation of

the same-sex beloved as an object of identification (as in Freud), but also

as the lover's outward inscription of the beloved onto her own body in

the form of gendered clothing, gesture, and so on.

Though her focus here is not queer performance but heterosexual

embodiment, Butler's use of the term "allegorize" in a discussion of how

drag might expose the psychic machinery of normative gender

identification is key, for allegory itself has an affinity with ritual. Both

engage with temporal crossing, with the movement of signs, personified

as bodies, across the boundaries of age, chronology, epoch. But to use

an even more old-fashioned literary critical term, if drag works allegori

cally, normative masculinity and femininity might actually be symbolic in

their to fuse incommensurate moments into a

attempt temporal singu

lar and coherent experience of gendered selfhood.10 Turning identi

fication into identity, ordinary gender must perforce erase the passage

of time, because it can only preserve the lost object of homosexual

desire in the form of the lawfully gendered subject by evacuating the

historical specificity of the prior object. For instance, if I renounce my

mother and wear her as "own" I don't wear it

body my gender, certainly

as she did at the moment of my renunciation, circa 1969. If I disseminate

my mother's body in all its anachronistic glory onto the surface of my

own, though, I don't look normative at all. As "Mom, circa 1969," my

appearance writes onto my body not only the history of my love for my

mother (or even the spending of her youthful body on the making of

my own), but also at least two historically distinct forms and of

meanings

"womanhood." This kind of temporal drag uses disruptive anachronisms

to pivot what would otherwise be simple parody into a montage of

publicly intelligible subject-positions lost and gained. For many commit

ted to both butch/femme and feminism, play on the flesh with prior,

"tired" models of gender performs just the kind of temporal crossing

that a certain

registers queerness.

Butler's momentary reference to allegory also goes beyond psycho

analysis to commit to the culture-making work of queer performativity.

For allegory is the form of collective melancholia. Melancholia is inward,

and involves the preservation of the lost object as an aspect of one

grieving person's subjectivity. But allegory traffics in collectively held

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

734 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

meanings and experiences, pushing the melancholic's rather solipsistic

introjection back outwards in order to remake the world in a mock

imperialist gesture: its narrative "cure" can never be merely personal.

The primary work of queer performativity, as

rethought complexly

allegorical, might be to construct and circulate something like an

embodied a archive for a form of

temporal map, political contingent

personhood.

This ethic deeply informs Subrin's casting and costuming in Shulie

(1997), which insists upon the presence of a shared feminist repository

in the 1990s queergirl.11 Lead actress Kim Soss's performance of Shulie,

and Subrin's direction of that performance, neither pass as perfect

reconstructions nor explode into hyperbolic deconstructions. Instead,

they traffic in the kinds of anachronisms that disrupt what might

otherwise be a seamless, point-by-point retelling of the prior text. For

instance, playing the part of Shulie, Soss wears a rather obvious wig and

glasses that look contemporary. Some of the video's critics have also

commented that the main difference between Soss and the Firestone of

the 1967 Shulie is affect?a reviewer who has seen both works focuses on

the contrast between Firestone's rather tortured emotional and

intensity

Soss's "colorless, vacant" There are also

guarded, emotionally delivery.12

several anomalous in the 1997 video, a

historically objects including

sexual harassment policy statement in the post office that Subrin used to

remake the scenes of Shulie at her day job, a Starbucks coffee cup, and

a cameo Subrin herself. But these anachronisms of

appearance by

costuming, affect, props, and character, which break the 1960s frame, do

not function as are neither excessive nor

parody. They particularly

funny. They are simultaneously minor failures of historical authenticity

and the sudden punctum of the present. The idea that Shulie's pigtails,

wacky glasses, minidresses, and depression might be all that is left of the

movement she founded is a sobering reminder that political contexts

morph rapidly into commodified subcultures. Or perhaps it is inspiring,

insofar as she looks a bit like a Riot Grrrl, that this movement has

reinvigorated some important precepts of radical feminism. But the

subtle 1990s touches work against the neoconservative tendency to

to the irretrievable past anything that challenges a dominant

consign

vision of the future?and remind us that social progressives have a

to be too easily embarrassed by earlier moments.

tendency political

Shulie's "now" clearly resonates with our own, and since hers was about

to detonate into a political future, the video implicitly asks, why not

ours?

In short, Shulie (1997) suggests that there are iterations, repetitions,

and citations which are not strictly parodie, in that they do not

necessarily aim to reveal the original as always already a copy, but instead

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PACKING HISTORY, COUNT(ER)lNG GENERATIONS 735

engage prior time as genuinely

with elsewhere. Nor are they strictly

consolidating of authority, in that they leave the very authority they cite

visible as a ruin. Instead, they tap into a mode of longing that is as

fundamental to queer performance as laughter is. cultural

Reanimating

corpses, Shulie's iterations suggest, might make the social coordinates

that accompanied these signs available in a different way.

This strategy both extends and modifies an earlier tradition of the

feminist reshoot pioneered by artists such as Sherrie Levine, Cindy

Sherman, and Barbara Kruger, who imitated high cultural masterworks

or popular generic codes, forcing viewers to

speculate upon what female

reauthorship (for all three) or the insertion of a "real" female body into

these frameworks (for Sherman and Kruger) might reveal about their

ostensibly universal representational stakes.13 Both Subrin and Firestone

herself do the same for the documentary genre. The anachronistic

touches which remind us that the Shulie of 1997 is not a historical

documentary also reframe Firestone's to resist her

temporally struggle

as a woman in the arts and to subvert the demand that she

position

represent the

"Now generation" of

1967, putting her instead into a

dialogue with feminist artists who followed her. In a scene that sets the

terms for her later critique of the representational of the

politics

"generation," Shulie takes her artwork into the painting studios at the

Art Institute for a final critique. Though her paintings look expressionist

and somewhat abstract, her five male teachers mistake her for a realist,

that several works "are what are." also turn Shulie

insisting they They

into a documentar?an, insisting that "the theme behind" all of her

is "the same, is your interest in and the lives. . . ."

photographs people,

This is a manifestly ludicrous assessment of even the most flatly

"realistic" photographs, since the central object her art examines is

the male male nudes, seated construction workers,

clearly body: figures,

little boys, and civil servants crowd her works. Even the 1967 filmmakers

seem to catch this irony, for a male figure

they shoot Shulie painting

from behind the canvas, so that she seems to look back and forth at the

camera as she as if the cameraman himself were her model.

paints, (Late

in the sequence, the "real" model

finally appears.) thus Firestone

explored the fragilities and cultural

distortions of male embodiment

long before "masculinity studies" hit the academy. And even the four

male documentarians of 1967 seem to have realized that Firestone was

clearly painting against the male gaze while a total of nine men looked

at "Shulie." Her teachers do not seem to have been so

bright. Dismissing

this work with the male body and the male social subject as

"grotesque,"

"a little on the dreary side," and "very indecisive," the art faculty pushes

her toward filmmaking, claiming that cinema is a more direct treatment

of reality.

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

736 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

Theirony of this is palpable

too, since Firestone is clearly already

working at and in the medium

of film by performing the part of the

"documentary" subject Shulie, all the while undermining the assump

tions behind the documentary genre. As if to contradict her professors'

banal assessment of her artwork, the glimpses we can see of Firestone's

engagement with the filming process stubbornly take issue with the idea

that can ever be "what are." She her

representations they emphasizes

commitment to depicting and deforming the male body while she

herself is framed both by the original male documentarians and by the

faculty members who critique her, and it is unclear whether these male

an act of conventions

grotesques represent revenge against patriarchal

of or her own as male.

representation gender-transitive self-figuration

She describes her decision to photograph an elderly woman,

not stating

firmly that "sometimes you just reach a point where you can't use

people's situations as subject matter," which suggests that she herself

may not be revealing much. And she offers only one coherent reading of

her own canvases. "This is a civil service exam," she and

explains,

links that to the very scenario she is in: ". . . or any

immediately painting

classroom situation ... a certain dehumanization and alienation that

people have to go through in their work," linking the use of the female

body in high art, her own position as a female art student in an all-male

critique, and her status as the object of the documentary gaze.

Yet Subrin also refuses to simply reinstall Shulamith Firestone into a

linear feminist art In a and scene that

history. complicated confusing

follows the art critique, Shulie herself goes on to explicitly repudiate the

cultural of whereby "generation" is an unquestion

logic reproduction

able figure either for continuity or for rupture?and by

complete

repeating this scene, the 1997 video complicates the relationship

between Shulie and her reanimator, younger and older, pre-feminist

and post-feminist. In the 1997 version, Subrin (who plays the on- and off

camera part of the original documentarians), asks Shulie if her feelings

of connection to outsiders relates "to this of a

question being genera

tion." Coming from a man as it did originally, this question would sound

narrow-minded, for it misrecognizes as a what Shulie's

generation gap

artwork has

already clearly rendered as a gender gap. But because

Subrin herself takes over the documentar?an 's authoritarian, misguided

voice, gender does not simply trump generation, linking women across

time. The scene also captures the failure of two women to constitute a

political cohort, of Second Wave and Generation X to

meaningful

merge smoothly into some timeless Generation XX. Shulie repeats the

question about "being a generation" in surprise. The documentar?an

says, "Imean, this is something that's very strong among so many people

your age, that they see themselves to be part, very importantly, a part of

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PACKING HISTORY, COUNT(ER)lNG GENERATIONS 737

an important generation." Because Subrin's impatient voice comes from

the 1990s, "your age" is ironic, suggesting her own slight irritation with

"'60s radicals" as the most co

perhaps self-consciously "generational"

hort, paying wry homage to the fact that women from the "important

generation" of the 1960s now make major decisions about the careers of

women like Subrin herself, and implying that age is often simply a

metaphor for institutional power.

But Shulie retorts, "Well, I wouldn't say that there are so many who

feel alienated from it," apparently shifting the pronominal referent

from mainstream society to the "Now generation" itself and thereby

even shared outsiderhood as a form of Here, she

dismissing groupthink.

seems to hold out for a feeling of alienation that might lead to

besides a generation gap, as indeed the subsequent

something depar

ture of many feminists from the traditional left acknowledged. The

documentar?an reiterates, "I'm that there are who feel

saying many part

of it, not who feel alienated, but who feel very much a part of it." "Oh,"

says Shulie, 'You said that they feel part of it, and I said I didn't." The

documentar?an assents. "Well," Shulie says, apparently giving up on

pursuing her discomfort with the idea of a collectivity whose main claim

to politics is being born within a few years of one another or

witnessing

the same events 'Yes, know. That's true." But she does not

together, you

seem to mean this any more than she does when she

gives up and agrees

with the cruel dismissals of her work in her art critique.

This conversation about adds another of

generations layer irony:

though Shulie could not possibly feel a part of Subrin's generation,

Subrin's address to the past suggests that Shulie might have done better

"here." For Firestone's later insistence on as the to

cybernetics key

feminist liberation ismore in keeping with the antiessentialist theories

in which Subrin was trained in the 1980s and 1990s than with what has

been critically associated with "Second Wave" feminism. Subrin, on the

other hand, seems to feel herself more part of Shulie's "pre"-feminist

moment than her own one: there is about the

"post"-feminist something

rawness of expression, the lack of terms with which Shulie has to think

about her own that the video as a mode of

experience, captures political

possibility. B. Ruby Rich insists that Subrin's version of Shulie "com

pletes a certain cycle: the first of feminist as revisited,

generation theory

fetishized, and worshipped by the new generation."14 But I am not sure

the language of worship does justice to the profound ambivalence of the

video, which is as accusatory as it is reverential, as much about the lack

of a genuinely transformed context for women born into the 1970s and

1980s as it is about an admiration for ideas that came earlier. If anything,

Subrin refuses to fetishize, to disavow what is not present in her primal

encounter with Shulie (at the very least, the "real" Firestone, a fully

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

738 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

available past, a coherent origin for radical feminism, and an intelligible

political doctrine) or to cover up that lack with the false totality of

interviews with Firestone's friends or with her own voice-overs.

The conversation between Shulie and the documentar?an about

bridges a scene emphasizing the uselessness of the "Now

generations

generation" concept that the original documentary's patrons aimed to

a 1960s "be-in," the scene was reshot at a demon

promote. Originally

stration against the 1996 Democratic National Convention in Chicago.

The 1990s demonstrators mill about, painting each other's faces and

banging drumsrather languorously, flanked by equally idle policemen.

One wonders whether the original be-in was this lackadaisical, or

whether the relaxed silliness of the 1990s version holds different

promises than the original event. Shulie's voiceover suggests that the be

in, like the free-form demonstration Subrin substitutes, relied on the

of belonging to a specific historical

politics "generations," whereby

moment?marked stratification, fashion, a

by age homogeneous vague

awareness of the are there to contest, and

politics they supposedly

indulgent supervision by the police?is somehow equated with doing

in it. As the scene rolls by, Shulie reiterates her feeling that

something

she is not part of the very generation the documentary insists she is

representing, "Well, I know that's not very hip. I'm sorry, it just happens

to be true." The documentar?an asks urgently, "Why?What's hip? What's

"To live in

your definition of hip?" Shulie replies, "To live in the now."

the now}" the documentar?an reiterates. "Where's that?"

This is perhaps the crucial Cultural Studies question?and the one

Subrin is clearly trying to answer for 1990s feminism. In the video's only

moment of genuine parody, Shulie replies by rattling off the mantras of

live-and-let-live "Don't about tomorrow, live in the

hippiedom. worry

now. . . . Life is fun, life is pleasant, we friends and and

enjoy drinking

. . . In the same

smoking pot why should we worry about anything?"

breath, she emphatically rejects this outlook: "Sure, that's fine, good for

them. I don't care. I want to it some form." Here and in other parts

give

of the documentary, she seems to be speaking only of artistic form: she

says that "Reality is a little chaotic and meaningless, and unless I give it

some form, it's just out of control"; she declares that "I hate any date that

some kind of landmark. ... I hate the

goes by that I haven't made

of it. . . . It's not for me to live and die; I don't

shapelessness enough just

like it enough." But it turns out that her interventions were already

collective, and historicist, and not just individualist and aes

political,

of 1967

thetic in the way her comments imply. For the documentarians

the wrong locale for "Now," and the "Shulie" character does not

picked

clue them in to what Firestone was apparently doing during the film's

production.

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PACKING HISTORY, COUNT(ER)?NG GENERATIONS 739

In fact, Firestone seems to have hidden from the 1967 documentar

ians her activities with Chicago's Westside group, the first radical

feminist group in the country (DB 65-66). These activities appear only

in her vague statements that sexual involvements with men who agree

with her on "these sorts of things" have not been a problem, and that

men "don't agree with this, still." In both the 1967 and the 1997 versions,

the question remains open whether the "things" in all of these state

ments were, at the moment of the filming, her individual pursuit of

artistic or intellectual work, her private views about gender roles, or her

activities in a movement. Even in the original film, the crucial political

referent is

missing.

Though she seems to be speaking the language of the alienated,

anticommunal, formalist artist, Shulie also a clue to the

resolutely gives

historical method she herself employed a short time later and that

Subrin herself reworks: she says she would like to "catch time short, and

not just . . . drift along in it." And by the time Firestone wrote The

Dialectic of Sex in 1970, she had fleshed out her relationship to the

generational logic she resisted in Shulie (1967). In her manifesto, she

describes "Woodstock Nation, the Youth Revolt, the Flower and Drug

Generation of Hippies, Yrppies, Crazies, Motherfuckers, Mad Dogs, Hog

Farmers, and the like, who [reject Marxist analysis and techniques] yet

have no solid historical analysis of their own to replace it; indeed, who

are apolitical" (DS 44). To make alienation genuinely political, she

insists, one must have a relationship to history. But The Dialectic of Sex is

linear, and monocausal in a way that other feminisms have

evolutionary,

decisively rejected, for it narrates a history of gender as the foundational

basis for oppression, one that class and upon which capitalism

predates

still feeds.

In a countermove, however, the Firestone of The Dialectic also disrupts

the "revolutionary" of her own feminist peers. She claims

presentism

that that "feminism, in truth, has a cyclical momentum all its own" (DS

35). For Firestone, this momentum involves the freeing of women from

biology by science, the development of political ideas from the sense of

possibility engendered by technological liberation, and inevitably, a

decades-long backlash that reduces those political ideas to a demand for

equal rights rather than the remaking of social relations. While her

biological determinism and faith in technology feel untenable today,

her use of feminist history ismore promising. She claims that the radical

feminist position of the late 1960s and early 1970s is the "direct

descendant of the radical feminist line in the old movement"

and

the very activists whom

rehabilitates her own feminist peers rejected

(DS

42). She describes the early American Women's Rights Movement

(which she calls the W.R.M.) as a radical grassroots agenda bent on

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

740 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

transforming Family, Church, and State, and eventually overwhelmed by

the "frenzied feminine organizational activity of the Progressive Era"

and the single-issue suffragists (DS 21). Of course this rehabilitation was

in many ways no different from any back-to-the roots resurrection of lost

political moments; Firestone merely asked her fellow activists to think in

terms of radical and conservative versions of the politics that travel

under the of feminism, rather than in terms of horizontal

sign genera

tional breaks with the past.

But in her sense of a disaggregated, cross-temporal identification,

Shulie was not unlike the student who intervened upon my own

sense of a coherent now. For she also avoided what

complacent political

Julia Creet has analyzed as the S/M fantasy of intergenerational contact

between feminists, where outlawism is practiced primarily in relation to

older women.15 While this model was clearly informing Firestone's

peers' rejection of the W.R.M., Firestone introduced a different politics

of the gap: rather than the inevitable "generation gap" that supposedly

aligns members of a chronological cohort with one another as they

move from their she concentrated on the amnesiatic

away predecessors,

gaps in consciousness that resulted from the backlash to the first W.R.M.

Elliptically relating the earliest W.R.M. to her own moment just as

Subrin elliptically relates the moment preceding radical feminism to our

own, Firestone let a former feminism flare up to illuminate the Second

Wave's moment of danger, which was indeed played out in the reduction

of radical feminism to the E.R.A. movement.

In an important point of contrast

to Firestone herself, though, Subrin

resists the rehabilitative

gesture that would position the former as a

heroic figure upon whom a better future feminism might cathect. For

Subrin deploys the figure of a woman younger than herself, complicat

ing that figure's situation earlier in time: in Shulie (1997), the elder is

also a Neither foremother, nor nor

younger. political peer, wayward

daughter, Shulie, like "Now," is multiply elsewhere. This elsewhere is

to Subrin's own moment and to the context in which

particular political

Shulie (1997) was produced and is currently received, in which the figure

of the young girl illuminates so many 'zines, manifestoes, and other

cultural productions.16 The middle-aged Firestone has refused to coop

erate with and so far will not comment upon Shulie, but Subrin's

insistence on taking the younger Firestone seriously as a political thinker

and an object of obsession, represents a commitment to the "girl" icon

of her own contemporary political context.

The deployment of the girl in recent queer/feminist videos, 'zines,

song lyrics, and so on, implicitly critiques radical feminists' repudiation

of their own 1950s girlhoods as false consciousness, allowing the

politicized adult a more and even erotic to her

empathetic relationship

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PACKING HISTORY, COUNT(ER)?NG GENERATIONS 741

former vulnerabilities and pleasures: "girl" embraces an embarrassing

past as the crucial augur of a critical, yet also contingent future. The

"girl revolution" implicitly critiques any lesbian and gay movement

politics that would disavow children's sexuality. Instead these works

willingly expose the fantasies, desires, and sexual experiments of child

hood, and seem to epitomize Eve Sedgwick's suggestion that a genuinely

queer politics must refuse to abject even the most stigmatized child-figure

from formulations of adult political subjectivity.17 But the "girl" revolu

tion also refuses to locate the "girl" as the beginning of either identity or

politics; instead, she represents what Elspeth Probyn calls "a political

tactic . . . used to turn inside out."18 The

identity girl-sign acknowledges

an uncontrollable the uncontrollability

past, of the past, its inability to

explain the present?and the promising distortions effected when the

past suddenly, unpredictably erupts into the present forms of sexual and

gendered personhood.

Yet the sign of the girl ismore than just that of an individual woman's

or unruly unconscious. distance from the child

personal past Refusing

self becomes a means of critiquing contemporary public culture in the

1997 Shulie, in Subrin's other recent videotape Swallow, in the works she

has produced with Sadie Benning,19 and in the 'zines and videos of the

1990s. In these texts, "girl" is a gendered sign of longing for the cultural

reorientation that Firestone advocated in The Dialectic of Sex and that the

1970s took more seriously than subsequent decades have: the constitu

tion of children as members of a distinct public, whose socialization and

demands might be thought collectively.20 "Girl" productions often

reference "Free to Be You and Me," Schoolhouse Rock, Head Start, Amy

Carter, and other of a culture that was, for at least a brief moment,

signs

genuinely hopeful about the relationship between children and the

mass media. of 1970s culture are more than mere

Reappropriations

on the part of a cohort born after 1965: the dissemination of

nostalgia

"girl" as a political identity implies that the liberal feminist turn towards

rethinking the politics of bringing up baby might have represented a

turn from the broader social contexts in which occurs.

away parenting

Texts operating under the sign of "girl" also speak insistently of a

feminized, eroticized children's public sphere beyond even the most

"progressive" productions made by adults for children. In a sense, the

"girl" icon seizes the iconography of missing children and childhoods,

which Marilyn Ivy has persuasively read as a sign of the privatization of

culture,21 but uses it to disseminate children's and adolescents' public

cultures. The queer girl icon demands the transformation of sentimen

tal love for the "inner child" into both an acknowledgment of children

as sexual subjects and a collective reorganization of the conditions of

childhood itself. In The Dialectic of Sex, Firestone saw radical feminism as

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

742 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

incomplete unless it included the political and sexual liberation of

children, and Subrin's unsanctioned revivification of her elder in the

form of a younger self becomes the sign that that revolution may indeed

be in the works.

Shulie is not a child, yet her costuming and confusion contribute to a

childlike aspect that the 1990s "girl revolution" has transformed into a

body praxis at once allegorical and performative. The slogan of this

movement might be "regress for redress": adults in kidwear, emotions as

political expressivity, juvenilia as political tract. Neither is Shulie a sexual

icon, yet Subrin's illicit recreation of her resonates with the slightly

sadistic culture of queer fandom, in which stars' most vulnerable

younger (or aging) selves become the nodal points for shared feelings of

shame, defiance, and survival.22 Finally, Shulie's status as not-yet-identified

"adult woman," as "feminist," as "lesbian," as the or

(as representative

symbol of a completed movement) allows Subrin a point of entry into

the moment in terms other than Subrin's inter

contemporary "post."

vention offers a corrective to the idea that we can ever be in a

genuinely

can somehow

post-identity politics moment?unless "post" signify the

endless dispatches between past and present social and subjective

formations.

Shulie's promise lies in what the language of feminist "waves" and

queer sometimes effaces: the energy

"generations" mutually disruptive

of moments that are not yet past and yet are not entirely present either.

Shulie in 1967 is a figure who has not yet entered her own "history." As

such, she forces us to our historical our

reimagine categories, rethinking

own in relation to the rather than in relation to

position "pre-historical"

the relentlessly "post." The messy, transitional status of Shulie's thinking

asks us to imagine the future in terms of experiences that discourse has

not yet caught up with, rather than as a legacy passed on between

Reflecting on her own relationship to marxism in The

generations.

Dialectic Firestone writes, "If there were another word more all

of Sex,

embracing than revolution, we would use it" (DS 1). She claims the word

"revolution" not as inheritance, but rather as a for

placeholder possibili

ties that have yet to be articulated.

Queer theory has illuminated the ways in which conventional mascu

linity and femininity are themselves the "afterlife" of foreclosed same

sex desires. Shulie (1997) points us toward the identities and desires that

are foreclosed within

social movements, illuminating the often unex

pected effects deferred

of such identifications. The film animates

melancholia for both a collective political past and an individual

child-self, that there may also be a productive

subject's suggesting

afterlife to identities that seem foreclosed within the filmmaker's own

present tense: second-wave feminist, girlchild of the 1970s, even student.

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

PACKING HISTORY, COUNT(ER)lNG GENERATIONS 743

Subrin's "improper" attachment to the figure of Shulie suggests how

contemporary sexual and gendered publics, in refusing to mourn

properly and instead preserving melancholic identifications, might

us toward a barely-imagined future. If identity is always in

propel

temporal drag, constituted and haunted by the failed love-project that

precedes it, perhaps the shared culture-making projects we call "move

ments" do well to feel the tug backwards as a

might potentially

transformative part of movement itself.

University of California, Davis

NOTES

1 See Judith Butler, Gender Trouble (New York, 1990). In the context of an argument that

queer performativity represents the gay movement's dismissal of an earlier left commit

ment to socialism, Sue-Ellen Case writes that "'performativity' links 'lesbian' to the

tarnished, sweating, laboring, performing body that most be semiotically scrubbed until

the 'live'lesbian gives way to the slippery, polished surface of the market manipulation of

the sign" ("Towards a Butch-Femme Retro-Future," in Cross-Purposes: Lesbians, Eeminists,

and the Limits of Alliance, ed. Dana Heller [Bloomington, Ind., 1997], p. 210).

2 See Judith Roof, "Generational

Difficulties; or, The Fear of a Barren History," in

Generations: Academic Feminists

in Dialogue, ed. Devoney Looser and E. Ann Kaplan

(Minneapolis, 1997), pp. 71-72; and Dana Heller, "The Anxieties of Affluence: Move

ments, Markets, and Lesbian Feminist Generation (s)," in Generations, p. 322.

3 Shulamith Firestone, The Dialectic of Sex: The Case for Feminist Revolution (New York,

1970); hereafter cited in text as DS. On Shulamith Firestone's activities from 1967-1970,

see Alice Echols, Daring to Be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967-1975 (Minneapolis,

1989); hereafter cited in text as DB. For the purposes I use of clarity, "Shulie" to designate

the fictive subject of both documentaries, and "Firestone" the historical agent beyond the

1967 documentary's Similarly, "video" refers to Subrin's and

imagination. production,

"film" to the 1967 original. Wherever possible, I have also distinguished between the

earlier and later works with dates in parentheses. Shulie, dir. Elisabeth Subrin (Video Data

Bank, 1997). Screenings or of Shulie (1997) can be arranged the Video

purchase through

Data Bank, 112 South Michigan, Chicago, IL 60603; (312) 345-3550.

4 Shulie (1967) was made by Jerry Blumenthal, Sheppard Ferguson, James Leahy, and

Alan Rettig. The earlier film remains unavailable for viewing.

5 Elisabeth Subrin, personal conversation, fall 1999.

6 Elisabeth Subrin's Szvallow (Video Data Bank, 1995) concerns the links among

depression, anorexia, the acquisition of language, and the experience of growing up in the

context of 1970s feminism.

7 See Andrew Ross, "Uses of Camp," in his No Respect: Intellectuals and Popular Culture

(New York, 1989), pp. 135-70; and Richard Dyer, Heavenly Bodies: Film Stars and Society

(New York, 1987).

8 Elisabeth Subrin, "Trash: Value, Waste, and the Politics of Legibility" (presented at the

College Art Association Annual Conference, Los Angeles, February, 1999).

9 Judith Butler, The Psychic Life of Power: Theories in Subjection (Palo Alto, 1997); hereafter

cited in text as PL.

10 The classic work on the distinction between and is Paul de Man's

allegory symbol

Allegories of Reading: Figurai Language in Rousseau, Nietzsche, Rilke, and Proust (New Haven,

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

744 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

1979); see also Walter Benjamin, "Allegory and Trauerspiel," in The Origin of German Tragic

Drama, tr. John Osborne (London, 1977), pp. 159-235.

11 Again, a few rather plodding remarks on neither "lesbian" nor

terminology: "dyke"

cover, precisely, the commitment to playing with age that, as I discuss further on, marks

Shulie and many other recent cultural productions made by queer females. Yet "queer"

remains frustratingly gender-neutral, and does not do justice to the specifically femme

sensibilities also at work in some of these texts. Hence, some neologisms.

12 Jonathan Rosenbaum, "Remaking History," review of Shulie, Chicago Reader, 20 No

vember 1998, sec. 1: 48-49.

13 See RosalindKrauss, "The Originality of the Avant-Garde: A Postmodernist Repeti

tion," in Art after Modernism: Rethinking Representation, ed. Brian Wallis (New York, 1984),

pp. 13-29; also, more generally,

see the early 1980s debates on postmodernism in the

pages of the journal October.

14 B. Ruby Rich, Chick Flicks: Theories and Memories of theFeminist Film Movement (Durham,

N.C., 1998), p. 384.

15 Julia Creet, of the Movement: The Psychodynamics of Lesbian S/M

"Daughter

Fantasy," differences, 3.2 (1991), 135-59.

16 Needless to say, self-published 'zines move faster than academic publishing, but a

representative sampling of mid-1990s girls 'zines can be found in A Girl's Guide to Taking

Over theWorld: Excerpts from the Girl 'Zine Revolution, ed. Tristan Taormino and Karen Green

(New York, 1997).

17 Eve Sedgwick, "How to Bring your Kids Up Gay: The War on Effeminate Boys," in her

Tendencies (Durham, N.C., 1993), pp. 153-64.

18 Elspeth Probyn, "Suspended Beginnings: Of Childhood and Nostalgia," in her Outside

Belongings (New York, 1996), p. 99.

19 Judy Spots, dir. Sadie Benning and prod. Elisabeth Subrin (Video Data Bank, 1995).

20 For a seminal meditation on the politics of mourning for lost public cultures that also

insists upon maintaining clear distinctions between generations, see Douglas Crimp,

"Mourning and Militancy," October, 51 (1998), 3-18.

21 Marilyn Ivy, "Have You Seen Me? Recovering the Inner Child in Late Twentieth

Century America," in Childhood and the Politics of Culture, ed. Sharon Stephens (Princeton,

1995), pp. 79-102.

22 See Richard Dyer, "Judy Garland and Gay Men," in Heavenly Bodies, pp. 141-94.

This content downloaded from 170.140.26.180 on Fri, 9 Aug 2013 10:10:05 AM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Temporal DragDocument19 pagesTemporal DragRegretteEtceteraNo ratings yet

- In Transit: Being Non-Binary in a World of DichotomiesFrom EverandIn Transit: Being Non-Binary in a World of DichotomiesRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (6)

- Jay Prosser Second Skins The Body Narratives of Transsexuality 1 PDFDocument280 pagesJay Prosser Second Skins The Body Narratives of Transsexuality 1 PDFJuliana Fausto Guarani-Kaiowá100% (7)

- Turner 2016 AComing Out Narrative Discovering My Queer VoiceDocument12 pagesTurner 2016 AComing Out Narrative Discovering My Queer Voicemetalman95No ratings yet

- Bush Theater MagazineDocument2 pagesBush Theater Magazineapi-545216149No ratings yet

- Living with Crossdressing: Discovering Your True Identity: Living with Crossdressing, #2From EverandLiving with Crossdressing: Discovering Your True Identity: Living with Crossdressing, #2No ratings yet

- Monk, Circa 1250. I Was Thinking About What My Life Would Have Been Like HadDocument2 pagesMonk, Circa 1250. I Was Thinking About What My Life Would Have Been Like HadJorge Luiz MiguelNo ratings yet

- Southbound: Essays on Identity, Inheritance, and Social ChangeFrom EverandSouthbound: Essays on Identity, Inheritance, and Social ChangeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (3)

- Off Our Backs - Bev Jo - Politics of Butch and FemDocument2 pagesOff Our Backs - Bev Jo - Politics of Butch and FemigaNo ratings yet

- Eddies Along the River: Reassembled, recovered, and realized tales of mid-century St. PaulFrom EverandEddies Along the River: Reassembled, recovered, and realized tales of mid-century St. PaulNo ratings yet

- Hierarchies of OthernessDocument4 pagesHierarchies of OthernesssaanyaNo ratings yet

- Aberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color CritiqueDocument33 pagesAberrations in Black: Toward a Queer of Color CritiqueMichael LitwackNo ratings yet

- Theorizing Queer Temporalities: A Roundtable DiscussionDocument20 pagesTheorizing Queer Temporalities: A Roundtable DiscussionJapan Of Green GablesNo ratings yet

- The Secret Life of Stories: From Don Quixote to Harry Potter, How Understanding Intellectual Disability Transforms the Way We ReadFrom EverandThe Secret Life of Stories: From Don Quixote to Harry Potter, How Understanding Intellectual Disability Transforms the Way We ReadRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Framing IdentityDocument12 pagesFraming Identityapi-645231662No ratings yet

- Not Your Average Zombie: Rehumanizing the Undead from Voodoo to Zombie WalksFrom EverandNot Your Average Zombie: Rehumanizing the Undead from Voodoo to Zombie WalksNo ratings yet

- Adrian-Piper-Notes-On-The-Mythic-Being OCR ResizeDocument13 pagesAdrian-Piper-Notes-On-The-Mythic-Being OCR Resizedsh265No ratings yet

- Bringing LGBTQ Voices to Light in English ClassDocument5 pagesBringing LGBTQ Voices to Light in English ClassSze Ting WangNo ratings yet

- Cynthia A. Young - Soul Power - Culture, Radicalism and The Making of A U.S. Third World Le PDFDocument314 pagesCynthia A. Young - Soul Power - Culture, Radicalism and The Making of A U.S. Third World Le PDFmi101No ratings yet

- Re-Reading Sexuality As A Life PracticeDocument18 pagesRe-Reading Sexuality As A Life PracticePeter BankiNo ratings yet

- Contingent Ontologies Sex, Gender and Woman' in Simone de Beauvoir and Judith Butler (And MP) : STELLA SANDFORDDocument12 pagesContingent Ontologies Sex, Gender and Woman' in Simone de Beauvoir and Judith Butler (And MP) : STELLA SANDFORDConall CashNo ratings yet

- Reflections On Compulsory Heterosexuality by Adrienne Cecile RichDocument4 pagesReflections On Compulsory Heterosexuality by Adrienne Cecile Richdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Pilgrim Acceptance Donna HarawayDocument17 pagesPilgrim Acceptance Donna HarawayCarlos CalentiNo ratings yet

- When lesbians were not defined by genderDocument15 pagesWhen lesbians were not defined by genderÉrica Sarmet100% (1)

- Something Queer HereDocument17 pagesSomething Queer HereRebecca EllisNo ratings yet

- Victorian Poetry Explores Female IdentityDocument64 pagesVictorian Poetry Explores Female IdentityAnonymous IC3j0ZSNo ratings yet

- Over The Course of This SemesterDocument3 pagesOver The Course of This Semesterjosephmainam9No ratings yet

- Gender Stories and Self-PortraitsDocument5 pagesGender Stories and Self-PortraitsNathan John MoesNo ratings yet

- Module 1 (Week 1)Document5 pagesModule 1 (Week 1)Niña Rica DagangonNo ratings yet

- Hey, I Still Can't See Myself!: The Difficult Positioning of Two-Spirit Identities in YA LiteratureDocument13 pagesHey, I Still Can't See Myself!: The Difficult Positioning of Two-Spirit Identities in YA LiteraturegwrjgNo ratings yet

- Attributing Authorship An Introduction - (CHAPTER SEVEN Gender and Authorship)Document13 pagesAttributing Authorship An Introduction - (CHAPTER SEVEN Gender and Authorship)Nikola NikolajevićNo ratings yet

- Earl Jackson Strategies of Deviance - Studies in Gay Male Representation - Theories of RepresentationDocument632 pagesEarl Jackson Strategies of Deviance - Studies in Gay Male Representation - Theories of RepresentationMayanaHellen100% (1)

- Berghahn BooksDocument32 pagesBerghahn BooksJulie_le145100% (1)

- Daumer, Elizabeth - Queer Ethics Or, The Challenge of Bisexuality To Lesbian Ethics PDFDocument16 pagesDaumer, Elizabeth - Queer Ethics Or, The Challenge of Bisexuality To Lesbian Ethics PDFDerin KormanNo ratings yet

- Positionality NarrativeDocument8 pagesPositionality Narrativeapi-456084262No ratings yet

- Theorizing Queer TemporalitiesDocument20 pagesTheorizing Queer TemporalitiesAntoniaNo ratings yet

- W.E.B. Du Bois Institute Passing ReviewDocument30 pagesW.E.B. Du Bois Institute Passing ReviewNickoKrisNo ratings yet

- Spring 23 Reflections Print 1Document4 pagesSpring 23 Reflections Print 1api-685635159No ratings yet

- Morehshin AllahyariDocument3 pagesMorehshin AllahyariIkram Rhy NNo ratings yet

- Download Lesbian Potentiality And Feminist Media In The 1970S A Camera Obscura Book Rox Samer full chapterDocument77 pagesDownload Lesbian Potentiality And Feminist Media In The 1970S A Camera Obscura Book Rox Samer full chapterandrew.gonzalez187100% (6)

- Obcenity, Gender and SubjectivityDocument93 pagesObcenity, Gender and SubjectivityBaratsu AxbaltNo ratings yet

- Queer LavenderVisionDocument13 pagesQueer LavenderVisionpinguNo ratings yet

- 33IJELS 107202038 AnIntroduction PDFDocument2 pages33IJELS 107202038 AnIntroduction PDFIJELS Research JournalNo ratings yet

- QMagazine Fall IssueDocument44 pagesQMagazine Fall IssueJake ConwayNo ratings yet

- Bey-BlackTransFeminism(2022)Document53 pagesBey-BlackTransFeminism(2022)emiession.No ratings yet

- The University of Chicago PressDocument41 pagesThe University of Chicago PressTicking DoraditoNo ratings yet

- Placing The SelfDocument10 pagesPlacing The SelfIsabel GaviriaNo ratings yet

- Quare Studies or Almost Everything I Know About Queer Studies I Learned From My GrandmotherDocument26 pagesQuare Studies or Almost Everything I Know About Queer Studies I Learned From My Grandmothercrobelo7No ratings yet

- Sex - Textual Conflicts in The Bell Jar - Sylvia Plaths Doubling NeDocument16 pagesSex - Textual Conflicts in The Bell Jar - Sylvia Plaths Doubling NenutbihariNo ratings yet

- Bulletin of Spanish Studies: Hispanic Studies and Researches On Spain, Portugal and Latin AmericaDocument22 pagesBulletin of Spanish Studies: Hispanic Studies and Researches On Spain, Portugal and Latin AmericaDžidža BreNo ratings yet

- Hall Culture, Comunity, NationDocument8 pagesHall Culture, Comunity, NationHerrSergio SergioNo ratings yet

- Getting Queer:: Teacher Education, Gender Studies, and The Cross-Disciplinary Quest For Queer PedagogiesDocument24 pagesGetting Queer:: Teacher Education, Gender Studies, and The Cross-Disciplinary Quest For Queer PedagogiesKender ZonNo ratings yet

- Radical FeminismDocument34 pagesRadical FeminismAugusta SilveiraNo ratings yet

- 1613627823-RG Instructor Guide CompleteDocument28 pages1613627823-RG Instructor Guide CompletePriscila Andreza de Souza100% (1)

- The Complicated Terrain of Latin American Homosexuality: Mar Tin NesvigDocument41 pagesThe Complicated Terrain of Latin American Homosexuality: Mar Tin NesvigFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Alan Lightman, in Defense of DisorderDocument2 pagesAlan Lightman, in Defense of DisorderFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- 2015 Samek PDFDocument29 pages2015 Samek PDFFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- 2001 CaulfieldDocument42 pages2001 CaulfieldFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Rice UniversityDocument17 pagesRice UniversityFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Schizoid TreatmentDocument337 pagesSchizoid TreatmentHeronimas ArneNo ratings yet

- 2015 Samek PDFDocument29 pages2015 Samek PDFFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- 2012 Bastian DuarteDocument27 pages2012 Bastian DuarteFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Asian Carp: Threatening the Great LakesDocument5 pagesAsian Carp: Threatening the Great LakesSmk AlghozalyNo ratings yet

- TyrantsDocument23 pagesTyrantsFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Murnane - The Interior of GaaldineDocument14 pagesMurnane - The Interior of GaaldineFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Seeing Rare Birds Where There Are None: Self-Rated Expertise Predicts Correct Species 1 Identification, But Also More False RaritiesDocument14 pagesSeeing Rare Birds Where There Are None: Self-Rated Expertise Predicts Correct Species 1 Identification, But Also More False RaritiesFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Off Our Backs, Inc. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Off Our BacksDocument4 pagesOff Our Backs, Inc. Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Off Our BacksFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Feminism and Its Ghosts: The Spectre of The Feminist-As-LesbianDocument24 pagesFeminism and Its Ghosts: The Spectre of The Feminist-As-LesbianFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Mostly Straight Young Women Variations in Sexual Behavior and Identity DevelopmentDocument7 pagesMostly Straight Young Women Variations in Sexual Behavior and Identity DevelopmentFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Ancestry Report MM RevB PDFDocument9 pagesAncestry Report MM RevB PDFFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- ABC of Reading (Ezra Pound)Document205 pagesABC of Reading (Ezra Pound)Thomas Patteson67% (3)

- Compulsory Bisexuality The Challenges of Sexual Fluidity PDFDocument21 pagesCompulsory Bisexuality The Challenges of Sexual Fluidity PDFFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Preview of Controversial New ReligionsDocument20 pagesPreview of Controversial New ReligionsFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Identification Keys & The Natural MethodDocument46 pagesIdentification Keys & The Natural MethodFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- A New Paradigm For Understanding Women's Sexuality and Sexual OrientationDocument22 pagesA New Paradigm For Understanding Women's Sexuality and Sexual OrientationFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Birds of Central ParkDocument4 pagesBirds of Central ParkFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- CMP Senges Book SampleDocument40 pagesCMP Senges Book SampleFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- 240 540 1 SM PDFDocument10 pages240 540 1 SM PDFFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Flaubert, Foucault, and The Bibliotheque Fantastique - Toward A Postmodern Epistemology For Library Science PDFDocument19 pagesFlaubert, Foucault, and The Bibliotheque Fantastique - Toward A Postmodern Epistemology For Library Science PDFFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Flick - An Introduction To Qualitative ResearchDocument518 pagesFlick - An Introduction To Qualitative ResearchErnesto Santillán Anguiano100% (4)

- Module 12.4 Lesson Plan IDocument2 pagesModule 12.4 Lesson Plan IFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 1999, Vol. 77, No.Document14 pagesJournal of Personality and Social Psychology 1999, Vol. 77, No.globaleese100% (1)

- Haraway, Situated Knowledges PDFDocument26 pagesHaraway, Situated Knowledges PDFAlberto ZanNo ratings yet

- Paula E Hyman Jewish Feminism Faces TheDocument22 pagesPaula E Hyman Jewish Feminism Faces TheMariangeles PontorieroNo ratings yet

- Block-2 Gender and FamilyDocument37 pagesBlock-2 Gender and FamilySabariNo ratings yet

- Western MovementDocument5 pagesWestern MovementKee Jeon DomingoNo ratings yet

- Literatures of Madness - Disability Studies and Mental Health-Palgrave Macmillan (2018) PDFDocument248 pagesLiteratures of Madness - Disability Studies and Mental Health-Palgrave Macmillan (2018) PDFAndreea MoiseNo ratings yet

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (14)

- If I Did It: Confessions of the KillerFrom EverandIf I Did It: Confessions of the KillerRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (132)

- The Wicked and the Willing: An F/F Gothic Horror Vampire NovelFrom EverandThe Wicked and the Willing: An F/F Gothic Horror Vampire NovelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (21)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedFrom Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (109)

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansFrom EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Hey, Hun: Sales, Sisterhood, Supremacy, and the Other Lies Behind Multilevel MarketingFrom EverandHey, Hun: Sales, Sisterhood, Supremacy, and the Other Lies Behind Multilevel MarketingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (102)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassFrom EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (24)

- The Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical ChurchFrom EverandThe Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical ChurchRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

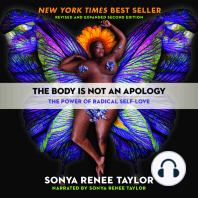

- The Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveFrom EverandThe Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (365)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldFrom EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1143)

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsFrom EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (386)

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionFrom EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (811)

- His Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsFrom EverandHis Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (100)