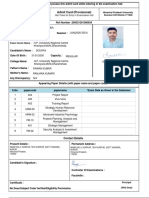

Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Reflections On Compulsory Heterosexuality by Adrienne Cecile Rich

Uploaded by

doraszujo19940 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views4 pagesThis document summarizes Adrienne Rich's reflections on her influential 1979 essay "Compulsory Heterosexuality". In 3 sentences:

Rich expresses that over time she became more critical of her own essay and felt it was flawed, outdated, and no longer fully representative of her thinking. She acknowledges it was a product of its time but believes the critique of the presumption of female heterosexuality as "beyond question" has had lasting usefulness. The responses to her essay in this journal issue from scholars addressing issues of race, disability, and history have sharpened her thinking on those topics and the complexities around defining and understanding sexuality and identity.

Original Description:

Original Title

Reflections on Compulsory Heterosexuality by Adrienne Cecile Rich

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentThis document summarizes Adrienne Rich's reflections on her influential 1979 essay "Compulsory Heterosexuality". In 3 sentences:

Rich expresses that over time she became more critical of her own essay and felt it was flawed, outdated, and no longer fully representative of her thinking. She acknowledges it was a product of its time but believes the critique of the presumption of female heterosexuality as "beyond question" has had lasting usefulness. The responses to her essay in this journal issue from scholars addressing issues of race, disability, and history have sharpened her thinking on those topics and the complexities around defining and understanding sexuality and identity.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views4 pagesReflections On Compulsory Heterosexuality by Adrienne Cecile Rich

Uploaded by

doraszujo1994This document summarizes Adrienne Rich's reflections on her influential 1979 essay "Compulsory Heterosexuality". In 3 sentences:

Rich expresses that over time she became more critical of her own essay and felt it was flawed, outdated, and no longer fully representative of her thinking. She acknowledges it was a product of its time but believes the critique of the presumption of female heterosexuality as "beyond question" has had lasting usefulness. The responses to her essay in this journal issue from scholars addressing issues of race, disability, and history have sharpened her thinking on those topics and the complexities around defining and understanding sexuality and identity.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 4

Reflections on "Compulsory Heterosexuality"

Adrienne Cecile Rich

Journal of Women's History, Volume 16, Number 1, Spring 2004, pp.

9-11 (Article)

Published by Johns Hopkins University Press

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.2004.0033

For additional information about this article

https://muse.jhu.edu/article/53008

[131.130.169.5] Project MUSE (2024-03-25 10:47 GMT) Vienna University Library

2004 ADRIENNE RICH 9

REFLECTIONS ON

“COMPULSORY HETEROSEXUALITY”

Adrienne Rich

O ver the twenty-three years since it was written, I probably became

more critical of my essay than any other possible reader. I stopped

giving permission for its inclusion in anthologies and college readers be-

cause I felt it flawed, outdated, and in certain important ways no longer

representative of my thinking and the thinking I respected. It also seemed

to me that the ensuing years produced more grounded scholarship, more

refined critical thinking, and, simply, more witnesses than were available

to me in 1979–1980 when I was writing it. “Compulsory Heterosexuality”

was an effort of the 1970s explosion of lesbian and feminist consciousness

in the United States, revolutionary in its activism and spirit, still groping

for historical, intellectual, and analytic tools.

It was also part of the writing catalyzed by newly emerging feminist

publishing venues: newspapers, magazines, presses, pamphlets, some

cranked out on workplace mimeograph machines, some financed by indi-

vidual women’s personal or collective assets, some funded by academic

institutions. Of the latter, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society,

was the most institutional, first established as a publication of the Univer-

[131.130.169.5] Project MUSE (2024-03-25 10:47 GMT) Vienna University Library

sity of Chicago, then transferred regularly to different universities under

different editors.1

I undertook “Compulsory Heterosexuality” at Signs’ invitation to

contribute to an issue on sexuality, from any perspective I chose. I thought

I was writing an exploratory piece, an essay in the literal sense of “at-

tempt”: a turning the picture—the presumption of female heterosexual-

ity—around to view it from different angles, a hazarding of unasked ques-

tions. That it should be read as a manifesto or doctrine never occurred to

me. When it began to be reprinted as a pamphlet by small lesbian-femi-

nist presses here and abroad, I was agreeably surprised. When I began to

hear that it was being claimed by some separatist lesbians as an argument

against heterosexual intercourse altogether, I began to feel acutely and

disturbingly the distance between speculative intellectual searching and

the need for absolutes in the politics of lesbian feminism.

Along with the elation—intellectual but also emotional—of that time

went, as I recall, a defensiveness, an impulse to label and condemn rather

than seek engagement and possible synthesis of views and positions. There

had never been a monolithic, unitary women’s movement. Yet the specter

of “splits” often led to blank non-engagement or public accusations of

© 2004 JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S HISTORY, VOL. 16 NO. 1

10 JOURNAL OF WOMEN’S HISTORY

“divisiveness.” (Through it all, of course, groups of women—the Combahee

River Collective being one notable example—were working seriously and

conscientiously to build alliances and define a viable, coherent multi-issue

politics.) In framing a “lesbian continuum” I was trying—somewhat clum-

sily—to address the disconnect between heterosexually-identified and les-

bian feminists.

There are moments of insight—the feminist identifying of institutional

patriarchy was one of them—that can seem to draw confirmation from

every direction, iron filings pulled to a magnet. Such moments can be elec-

trifying—and dangerous. To perceive human relationships in a different

pattern, to imagine new social possibility, is an extraordinary sensation.

But precisely at that point the self-critical function needs to come into play,

where, as contributors to the issue on my essay have pointed out, history,

context, supporting sources, need to be scrutinized.

What I believe has had lasting usefulness is the critique of the pre-

sumption that heterosexuality is “beyond question.” That new genera-

tions of young women have met with that critique for the first time in my

essay only indicates how deeply the presumption still prevails.

The essays by Judy Wu and Mattie Richardson draw on Asian and

African American studies and analysis developed over the past quarter-

century. The existence of such studies is owed to scholars and activists in

the queer and academic communities, and in the ongoing antiracism

struggle. Racialism is still the great bulging theme pushing at all political

and social movements—and underlying most discourse—in this country.

If my essay has lent any momentum to the work of such younger femi-

nists of color as Wu and Richardson, I am grateful to know it.

I would not have used the word “queer” in the late 1970s, and I use it

today to allude to many kinds of sexual disenfranchisement. But in writ-

ing “Compulsory Heterosexuality,” I was writing specifically about women

and feminism: hence “lesbian” was my term of choice.

Alison Kafer raises important questions as to definitions and

sexualizations around “disability.” Having lived with rheumatoid arthri-

tis for over half a century, I am incalculably indebted to the disability ac-

tivists—some of them lesbian/gay friends of mine—whose movement has

produced many kinds of changes, from cut-out curbs to heightened con-

sciousness on many scores. The movement for disability justice is a neces-

sary ongoing political and social process. I am also aware of the complexi-

ties of defining oneself as “disabled.” Kafer’s essay sharpened my sense

of our culture’s glorifications of “fitness” ranging from the marketing of

“perfect” bodies to huge monetary rewards for athletes to promotion of a

body builder as governor of California. Yet lack of universal health insur-

ance in the United States impinges on disabled people and on the “tempo-

2004 ADRIENNE RICH 11

rarily able-bodied” alike so that health itself is a luxury in this land of

wealth and poverty.

Joan Nestle’s integrity, courage, and concern for history and language

have been a challenge and inspiration to me for years, and her eloquent

essay in the Journal of Women’s History is no exception. I thank her for her

continuing honesty, her thinking in times of war, her memories of West

92nd Street, for the hospitality she and Deborah Edel extended to me at

the Lesbian Herstory Archives, and for their founding of that institution

dedicated to lesbian memory and witness.

Since “Compulsory Heterosexuality” was written, many changes have

taken place on the political and economic scene. I will mention only a few:

The cynical “trickle-down” economics of the Reagan administration and

the increasing bondage of both political parties to the protection of pri-

vate wealth have produced an ever-growing and deadly economic abyss

unlike any that existed earlier, despite class inequalities of the past. Fun-

damentalist religious ideology, along with blatantly criminal corporate

practice, has become incorporated into the highest councils of government.2

While more and more Americans feel disenfranchised and disempowered,

and more and more of our citizens are incarcerated, our government is

feared and hated throughout the world. The feminist search for justice

and freedom is inseparable from the concept of a truly integrated world

society. Its horizons have been and must go on being expanded to a de-

gree I did not yet envision when I wrote “Compulsory Heterosexuality.”

NOTES

1

The first “Lesbian Issue” of Signs was published at Stanford University as

Vol. 9, No. 4, Summer 1984, under the managing editorship of Barbara Charlesworh

Gelpi.

2

We now have a “born-again” President who professes to be God-appointed.

As Joan Didion has pointed out (New York Review of Books, vol. L, no. 17, November

6, 2003) it matters little if he is a true believer or cynically placating the Christian

Right: the effects on our polity—and specifically on foreign policy and women’s

freedom—are the same.

You might also like

- Narrative Psychology The Storied Nature of Human Conduct - Theodore R. Sarbin PDFDocument322 pagesNarrative Psychology The Storied Nature of Human Conduct - Theodore R. Sarbin PDFjanettst286% (7)

- When Lesbians Were Not WomenDocument15 pagesWhen Lesbians Were Not WomenÉrica Sarmet100% (1)

- Gender Studies and Queer TheoryDocument2 pagesGender Studies and Queer TheoryFelyn Garbe YapNo ratings yet

- Womanist Research PDFDocument11 pagesWomanist Research PDFÉrica nunes100% (1)

- Phish-Heads: Modern Society, Youth, and Identity (Undergraduate Honors Thesis)Document36 pagesPhish-Heads: Modern Society, Youth, and Identity (Undergraduate Honors Thesis)mweschNo ratings yet

- Sianne Ngai, EnvyDocument55 pagesSianne Ngai, EnvyPansy van DammenNo ratings yet

- Anne Frank Teaching ResourcesDocument68 pagesAnne Frank Teaching ResourcesLisa WardNo ratings yet

- Becoming A Agile Leader BLADDocument34 pagesBecoming A Agile Leader BLADMariana Magrini0% (1)

- Sample Letter of Recommendation (LOR) For MS Admission - Format 5 - US's BlogDocument2 pagesSample Letter of Recommendation (LOR) For MS Admission - Format 5 - US's Blogavinashappukuttan160392% (25)

- Mohanty Feminism Wihout Borders, 2003Document154 pagesMohanty Feminism Wihout Borders, 2003Isabel GaviriaNo ratings yet

- Sex and Negativity Or, What Queer Theory Has For YouDocument26 pagesSex and Negativity Or, What Queer Theory Has For YouSilvino González MoralesNo ratings yet

- Feminist and Queer Approach.Document27 pagesFeminist and Queer Approach.Ronnel LozadaNo ratings yet

- Inarticulacy, Identity and Silence - Annie Proulx's The ShippingDocument16 pagesInarticulacy, Identity and Silence - Annie Proulx's The ShippingDanaeGalloGonzalezNo ratings yet

- Black Fem PhilosopherDocument7 pagesBlack Fem PhilosopherBlythe TomNo ratings yet

- Theorizing Queer Temporalities: A Roundtable DiscussionDocument20 pagesTheorizing Queer Temporalities: A Roundtable DiscussionJapan Of Green GablesNo ratings yet

- Theorizing Queer TemporalitiesDocument20 pagesTheorizing Queer TemporalitiesAntoniaNo ratings yet

- Human Nature, Interest, and Power: A Critique of Reinhold Niebuhr’s Social ThoughtFrom EverandHuman Nature, Interest, and Power: A Critique of Reinhold Niebuhr’s Social ThoughtNo ratings yet

- The Erotics of Mourning in Recent Experimental Black PoetryDocument16 pagesThe Erotics of Mourning in Recent Experimental Black Poetryajohnny1No ratings yet

- Felman - Women and MadnessDocument10 pagesFelman - Women and MadnessDon SegundoNo ratings yet

- Book ReviewsDocument2 pagesBook ReviewsHeribertusDwiKristantoNo ratings yet

- Toward A Theory of Gendered ReadingDocument70 pagesToward A Theory of Gendered ReadingYasmin ShapanNo ratings yet

- Desiring WhitenessDocument193 pagesDesiring WhitenessSusanisima Vargas-GlamNo ratings yet

- Down The Rabbit-Hole: Girlhood, #Metoo, and The Culture of BlameDocument10 pagesDown The Rabbit-Hole: Girlhood, #Metoo, and The Culture of BlameLazaro PatricioNo ratings yet

- Brandy Daniels - Chrononormativity and The Community of Character - A Queer Temporal Critique of Hauerwasian Virtue EthicsDocument31 pagesBrandy Daniels - Chrononormativity and The Community of Character - A Queer Temporal Critique of Hauerwasian Virtue EthicsJohir MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Hein - The Role of Feminist Aesthetics in Feminist TheoryDocument12 pagesHein - The Role of Feminist Aesthetics in Feminist TheoryDolores GalindoNo ratings yet

- Feminist Criticism A Revolution of Thought A Study On Showalters Feminist Criticism in The Wilderness MR Hayel Mohammed Ahmed AlhajjDocument6 pagesFeminist Criticism A Revolution of Thought A Study On Showalters Feminist Criticism in The Wilderness MR Hayel Mohammed Ahmed Alhajjκου σηικ100% (1)

- Encounters With Alterity, by Tzu-Yu LinDocument205 pagesEncounters With Alterity, by Tzu-Yu LinhocicoNo ratings yet

- The Other Side of the Story: Structures and Strategies of Contemporary Feminist NarrativesFrom EverandThe Other Side of the Story: Structures and Strategies of Contemporary Feminist NarrativesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- The Johns Hopkins University PressDocument19 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University PressFrancisca Monsalve C.No ratings yet

- Adrian-Piper-Notes-On-The-Mythic-Being OCR ResizeDocument13 pagesAdrian-Piper-Notes-On-The-Mythic-Being OCR Resizedsh265No ratings yet

- Thinking Through Queer TheoryDocument11 pagesThinking Through Queer Theoryronaldotrindade100% (1)

- The Oxford Handbook of The SelfDocument26 pagesThe Oxford Handbook of The SelfVicent Ballester GarciaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 195.221.71.48 On Tue, 17 Aug 2021 09:11:59 UTCDocument7 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 195.221.71.48 On Tue, 17 Aug 2021 09:11:59 UTCThe Anti-Clutterist BlogNo ratings yet

- Utopian Studies and The Beloved CommunitDocument27 pagesUtopian Studies and The Beloved CommunitPedro José Mariblanca CorralesNo ratings yet

- Cognitive Contradictions and Universals - GoodyDocument16 pagesCognitive Contradictions and Universals - GoodyDustinNo ratings yet

- No Sex Please, We 'Re AmericanDocument11 pagesNo Sex Please, We 'Re AmericanVictor Hugo BarretoNo ratings yet

- Placing The SelfDocument10 pagesPlacing The SelfIsabel GaviriaNo ratings yet

- Audre Lorde & The Ontology of Desire-1Document48 pagesAudre Lorde & The Ontology of Desire-1Federica BuetiNo ratings yet

- Feminism, Foucault and The Politics of The BodyDocument24 pagesFeminism, Foucault and The Politics of The BodyAndrew Barbour100% (1)

- Making Meaning - Garth GreenwellDocument22 pagesMaking Meaning - Garth GreenwellNilo CacielNo ratings yet

- Pilgrim Acceptance Donna HarawayDocument17 pagesPilgrim Acceptance Donna HarawayCarlos CalentiNo ratings yet

- A Philosophy of Culture: The Scope of Holistic PragmatismFrom EverandA Philosophy of Culture: The Scope of Holistic PragmatismRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- De Acosta The Impossible Patience - Critical Essays 2007-2013Document316 pagesDe Acosta The Impossible Patience - Critical Essays 2007-2013nickNo ratings yet

- (Shubha Bhttacharya) Intersectionality Bell HooksDocument32 pages(Shubha Bhttacharya) Intersectionality Bell HooksCeiça FerreiraNo ratings yet

- New Feminist Work On Knowledge, Reason and ObjectivityDocument11 pagesNew Feminist Work On Knowledge, Reason and ObjectivityYöntem KilkisNo ratings yet

- Cornell Particulars - of - Rapture-An - Aesthetics - of - The - Affects Mar 2003 PDFDocument208 pagesCornell Particulars - of - Rapture-An - Aesthetics - of - The - Affects Mar 2003 PDFGajaules RaducanuNo ratings yet

- Nowhere or Somewhere Dis Locating GendeDocument21 pagesNowhere or Somewhere Dis Locating Gendeghonwa hammodNo ratings yet

- Breaking The Waves: The Care of The Self The History of SexualityDocument10 pagesBreaking The Waves: The Care of The Self The History of SexualityEileen A. Fradenburg JoyNo ratings yet

- Briggs - Activisms and EpistemologiesDocument18 pagesBriggs - Activisms and EpistemologiesSharmila ParmanandNo ratings yet

- 1 PB PDFDocument14 pages1 PB PDFelidolphin2No ratings yet

- Cynthia A. Young - Soul Power - Culture, Radicalism and The Making of A U.S. Third World Le PDFDocument314 pagesCynthia A. Young - Soul Power - Culture, Radicalism and The Making of A U.S. Third World Le PDFmi101No ratings yet

- 06 Chapter 1 PDFDocument37 pages06 Chapter 1 PDFShreya HazraNo ratings yet

- 4b. Engelberg. Cinematic Figurations of Bisexual TransgressionDocument33 pages4b. Engelberg. Cinematic Figurations of Bisexual Transgressionozen.ilkimmNo ratings yet

- Ejn TN Autobiography Conversion ParadigmDocument2 pagesEjn TN Autobiography Conversion ParadigmDr. Ted NewellNo ratings yet

- The Johns Hopkins University PressDocument37 pagesThe Johns Hopkins University PressLeonardo GranaNo ratings yet

- (Joanne D. Birdwhistell) Mencius and Masculinities (BookFi) PDFDocument170 pages(Joanne D. Birdwhistell) Mencius and Masculinities (BookFi) PDFRăzvanMituNo ratings yet

- Little Red Riding Hood: A Critical Theory ApproachDocument13 pagesLittle Red Riding Hood: A Critical Theory Approachthereadingzone50% (2)

- Freud and Literature PDFDocument10 pagesFreud and Literature PDFDaniel Franção StanchiNo ratings yet

- MORE CRITICAL APPROACHESTO COMICSDocument305 pagesMORE CRITICAL APPROACHESTO COMICSdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Graphic Novels and Comics as World LiteratureDocument3 pagesGraphic Novels and Comics as World Literaturedoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Superwomen Gender, Power, and RepresentationDocument3 pagesSuperwomen Gender, Power, and Representationdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- MichaelAChaney_2011_ContenDocument4 pagesMichaelAChaney_2011_Contendoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Handbook of Comics and Graphic NarrativesDocument646 pagesHandbook of Comics and Graphic Narrativesdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Routledge Companion to GenderDocument595 pagesRoutledge Companion to Genderdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Action WomenDocument18 pagesAction Womendoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Gender Schema and Prejudicial RecallDocument14 pagesGender Schema and Prejudicial Recalldoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Pragmatics and Children's LiteratureDocument18 pagesPragmatics and Children's Literaturedoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Comic Book MasculinityDocument48 pagesComic Book Masculinitydoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- First Pictures, Early Concepts - Early Concept BooksDocument25 pagesFirst Pictures, Early Concepts - Early Concept Booksdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Frame Escapes Graphic Novel IntertextsDocument232 pagesFrame Escapes Graphic Novel Intertextsdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Between Man and Machine The Liminal Superhero BodyDocument22 pagesBetween Man and Machine The Liminal Superhero Bodydoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- PICTUREBOOKS AND PAGE LAYOUT Megan Dowd LambertDocument12 pagesPICTUREBOOKS AND PAGE LAYOUT Megan Dowd Lambertdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Gender and Action FilmsDocument2 pagesGender and Action Filmsdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Kümmerling Meibauer Meibauer 2015 Maps in Picturebooks Cognitive Status ADocument10 pagesKümmerling Meibauer Meibauer 2015 Maps in Picturebooks Cognitive Status Adoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- CoatsDocument18 pagesCoatsdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Landscapes of Consciousness Reading Theory of Mind inDocument14 pagesLandscapes of Consciousness Reading Theory of Mind indoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Reynolds, K. Modern Childrens Literature. Chapters 1314Document23 pagesReynolds, K. Modern Childrens Literature. Chapters 1314doraszujo1994No ratings yet

- KummerlingMeiba 2011 7ReadingAsPlayingTheC EmergentLiteracyChildDocument26 pagesKummerlingMeiba 2011 7ReadingAsPlayingTheC EmergentLiteracyChilddoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Bettina Kümmerling-Meibauer and Jörg MeibauerDocument18 pagesBettina Kümmerling-Meibauer and Jörg Meibauerdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Joanne Marie PurcellDocument20 pagesJoanne Marie Purcelldoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- ContentsDocument4 pagesContentsdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Gardner Storylines 2011Document18 pagesGardner Storylines 2011doraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Kümmerling-Meibauer Meibauer - Picturebooks and Cognitive StudiesDocument12 pagesKümmerling-Meibauer Meibauer - Picturebooks and Cognitive Studiesdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Sequential Art: Kathrin Muschalik and Florian Fiddrich - 978-1-84888-447-2 Via Vienna University LibraryDocument96 pagesSequential Art: Kathrin Muschalik and Florian Fiddrich - 978-1-84888-447-2 Via Vienna University Librarydoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Witchcraft - The BasicsDocument200 pagesWitchcraft - The Basicsdoraszujo1994100% (1)

- Comics and LanguageDocument4 pagesComics and Languagedoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Comics and Graphic Novels Critical ApproachesDocument3 pagesComics and Graphic Novels Critical Approachesdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Reclaiming Tituba - What The Crucible Left OutDocument16 pagesReclaiming Tituba - What The Crucible Left Outdoraszujo1994No ratings yet

- Personal Project Process Journal TemplateDocument18 pagesPersonal Project Process Journal TemplatenandydsNo ratings yet

- Fs 2 Template - 071258Document69 pagesFs 2 Template - 071258Sheila Mae MontaNo ratings yet

- Statements of Inquiry in Individuals and SocietiesDocument4 pagesStatements of Inquiry in Individuals and SocietiesNishchithNo ratings yet

- Tour Guiding ScriptDocument5 pagesTour Guiding ScriptArjay SolisNo ratings yet

- Soal Letter For StudentsDocument18 pagesSoal Letter For StudentsGrace EliaNo ratings yet

- DIASS Q1 - LAS 6A RAreas of Specialization of CounselorsDocument1 pageDIASS Q1 - LAS 6A RAreas of Specialization of Counselorsshiella mae baltazarNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan On Cot #1 English 6: Caingin Elementary SchoolDocument4 pagesLesson Plan On Cot #1 English 6: Caingin Elementary SchoolNino IgnacioNo ratings yet

- NAAC Revised Accreditation Framework - 2020: Criterion 01 "Curricular Aspects"Document19 pagesNAAC Revised Accreditation Framework - 2020: Criterion 01 "Curricular Aspects"BasappaSarkarNo ratings yet

- Tiêu Chí Task Response Trong Writing Task 2 - Phân Tích Chuyên Sâu Theo Band 4, 5, 6Document12 pagesTiêu Chí Task Response Trong Writing Task 2 - Phân Tích Chuyên Sâu Theo Band 4, 5, 6Phuong MaiNo ratings yet

- Sylabus English Teaching TechniqueDocument6 pagesSylabus English Teaching Technique0056 ravicayaslinaNo ratings yet

- General BooksDocument122 pagesGeneral BooksZora DNo ratings yet

- Parent Handbook 2019 2020 FinalDocument39 pagesParent Handbook 2019 2020 FinalNajla NayefNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood Cover Letter SampleDocument8 pagesEarly Childhood Cover Letter Samplegag0besuhez2100% (1)

- Lalit Narayan Mithila University, DarbhangaDocument1 pageLalit Narayan Mithila University, DarbhangaMD dilshadNo ratings yet

- CTS G5-7 eBOOKDocument100 pagesCTS G5-7 eBOOKSamuel kasezhaNo ratings yet

- Admit CardDocument1 pageAdmit CardSobbyNo ratings yet

- KIHBT Advert APRIL 2013Document3 pagesKIHBT Advert APRIL 2013FortuneNo ratings yet

- IAL Edexcel Pure 4 Mathematics SBDocument192 pagesIAL Edexcel Pure 4 Mathematics SBMomen YasserNo ratings yet

- A Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in English 7 Guro: Baitang: I. Mga LayuninDocument2 pagesA Semi-Detailed Lesson Plan in English 7 Guro: Baitang: I. Mga LayuninAnabel BahintingNo ratings yet

- Meghan Maughan Official ResumeDocument2 pagesMeghan Maughan Official Resumeapi-302030328No ratings yet

- Example Prompt Formative Assessment Examples 2 Answer KeyDocument3 pagesExample Prompt Formative Assessment Examples 2 Answer Keyapi-544797221No ratings yet

- MadLibs Teachers Guide NocropsDocument12 pagesMadLibs Teachers Guide NocropsMayNo ratings yet

- Narrative Report of Launching and Orientation of NLC 23Document2 pagesNarrative Report of Launching and Orientation of NLC 23fe del rosario100% (2)

- Accomplishment MARCHDocument5 pagesAccomplishment MARCHsherlyn de guzmanNo ratings yet

- DEF Scholarship ApplicationDocument5 pagesDEF Scholarship ApplicationmortensenkNo ratings yet

- Grad School Personal StatementsDocument3 pagesGrad School Personal StatementsSiangNo ratings yet

- ResumEsq. Proyecto Max PlanckDocument20 pagesResumEsq. Proyecto Max PlanckLeonardo ArayaNo ratings yet