Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Roadblocks To Infection Prevention Efforts in Health Care: SARS-CoV-2:COVID-19 Response Saskia Popescu, PHD, MPH, MA, CIC

Roadblocks To Infection Prevention Efforts in Health Care: SARS-CoV-2:COVID-19 Response Saskia Popescu, PHD, MPH, MA, CIC

Uploaded by

M ThoriqOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Roadblocks To Infection Prevention Efforts in Health Care: SARS-CoV-2:COVID-19 Response Saskia Popescu, PHD, MPH, MA, CIC

Roadblocks To Infection Prevention Efforts in Health Care: SARS-CoV-2:COVID-19 Response Saskia Popescu, PHD, MPH, MA, CIC

Uploaded by

M ThoriqCopyright:

Available Formats

CONCEPTS IN DISASTER MEDICINE

Roadblocks to Infection Prevention Efforts in Health

Care: SARS-CoV-2/COVID-19 Response

Saskia Popescu, PhD, MPH, MA, CIC

ABSTRACT

The outbreak of a novel coronavirus, SARS-CoV-2, is challenging international public health and health

care efforts. As hospitals work to acquire enough personal protective equipment and brace for potential

cases, the role of infection prevention efforts and programs has become increasingly important. Lessons

from the 2003 SARS-CoV outbreak in Toronto and 2015 MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea have

unveiled the critical role that hospitals play in outbreaks, especially of novel coronaviruses. Their ability

to amplify the spread of disease can rapidly fuel transmission of the disease, and often those failures in

infection prevention and general hospital practices contribute to such events. While efforts to enhance

infection prevention measures and hospital readiness are underway in the United States, it is important

to understand why these programs were not able to maintain continued, sustainable levels of readiness.

History has shown that infection prevention programs are primarily responsible for preparing hospitals

and responding to biological events but face understaffing and focused efforts defined by administra-

tors. The current US health care system, though, is built upon a series of priorities that often view bio-

preparedness as a costly endeavor. Awareness of these competing priorities and the challenges that

infection prevention programs face when working to maintain biopreparedness is critical in adequately

addressing this critical infrastructure in the face of an international outbreak.

Key Words: biopreparedness, health care, hospital preparedness, infection prevention, pandemic

T he emergence of a novel coronavirus (SARS-

CoV-2) causing the disease, COVID-19, in

Wuhan, China, in late 2019 is currently test-

ing international public health and preparedness

health care facilities meet the guidance of the Centers

for Disease Control and Prevention and World Health

Organization. These strategies are in addition to daily

surveillance and reporting requirements, among other

efforts. As the cases of COVID-19 surge past 100 000 duties.

and over 1600 have been identified in the United

States, the question of capacity and preparedness IPC efforts have proven critical in previous coronavirus

comes into play. One arm of response lies within outbreaks because hospitals can easily act as amplifiers

health care. for disease. In 2003, the outbreak of SARS-CoV in

Toronto shed light on the ability for hospital transmis-

When responding to infectious disease threats, hospi- sion to fuel an outbreak. In Canada alone, 43% of the

tals lean heavily on the expertise and guidance of their cases were health care workers, and, in phase II of the

infection prevention and control (IPC) programs, outbreak and of the cases in Toronto, 72% were a result

which comprise infection preventionists. With back- of nosocomial transmission.2-4 In fact, health care

grounds in nursing, epidemiology, and microbiology, transmission rose from 17% in phase I to 88% in phase

it’s not surprising that IPC would lead such efforts, as II of the outbreak. Despite quarantine efforts put into

it is the intersection of health care and public health. place, the implementation of enhanced infection pre-

During the 2014 Dallas Ebola cluster, readiness efforts vention measures is widely considered to have been the

were led by primarily IPC and consumed 80% of their most effective in halting SARS-CoV transmission.

time, and 70% of daily infection prevention duties The relaxation of these efforts following phase I of

were not completed during this time.1 These IPC out- the outbreak resulted in the high rate of nosocomial

break efforts include education, reinforcement of infec- transmission and the second phase of the outbreak.

tion prevention standards like isolation and proper

usage of personal protective equipment (PPE), and The MERS-CoV outbreak in South Korea is also a les-

established processes to ensure that the i3 strategy son in IPC efforts during coronavirus outbreaks. Of the

(identify, isolate, and inform) is used and that the 186 cases identified in 2015, roughly 91–99% are

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 1

Copyright © 2020 Society for Disaster Medicine and Public Health, Inc. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Universitas Airlangga, on 21 Apr 2020 at 16:47:42, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. DOI: 10.1017/dmp.2020.55

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.55

Infection Prevention Roadblocks in Health Care

believed to be from health care transmission5,6; 83% of the employed infection preventionist for every 69 beds.10

MERS-CoV transmission events were a result of 5 super- Unfortunately, average staffing tends to be at 1 infection pre-

spreaders. This particular outbreak is relevant in that it was, ventionist for a minimum of 80–100 beds. More important,

largely in part, due to several factors: overcrowded emergency though, those IPC efforts tend to be focused on those

departments, delays in isolation, infection prevention failures, health-care-associated infection surveillance and reporting

utilization of family/visitors in the care process, multiple requirements that are linked to mandated reporting and

patients per hospital room, and hospital or doctor “shopping.” Medicare reimbursement. A 2013–2014 study found that these

Prior to a diagnosis, the index case-patient had contact with mandated reporting burdens consumed 5 hours a day for infec-

600 people across 4 health care facilities. The outbreak is par- tion preventionists.11 When put in the context of taking time

ticularly unique in that not only did intrahospital infections away from mandated reporting and reimbursement-associated

occur, but also hospital-to-hospital, which involved 17 hospi- infections, it’s not surprising that hospital administrators

tals, but ultimately originated from 1.7,8 The role of super- would prioritize those efforts over infectious disease events that

spreaders and a health care system using multiple patients are often perceived as unlikely. A 2018 Report by the Office

per room, coupled with infection prevention failures, is a sit- Inspector General of the US Department of Health and

uation ripe with potential for an explosive outbreak. Prolonged Human Services assessed hospital readiness to emerging

waiting times in crowded emergency rooms with no isolation infectious disease threats following the 2013–2016 Ebola

can also heavily contribute to the spread of respiratory infec- outbreak.12 The surveyed hospital administrators reported a

tions like coronavirus. higher level of preparedness but noted that emergency prepar-

edness personnel often lacked the specialized knowledge

These historical outbreaks of MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV required for infectious disease threats. Moreover, administra-

underscore the role of hospitals in disease transmission and tors noted that it was difficult to integrate procedures specific

the impact of infection prevention failures. A recent analysis to emerging infectious diseases, specifically IPC, into emer-

of 138 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in Wuhan, gency plans and that responding to such events was out of

China, has reiterated these critical lessons in outbreak the comfort zone for emergency preparedness coordinators.

response.9 Of the 138 patients hospitalized, 26% required Researchers found that, although a majority of hospital admin-

admission to the intensive care unit, which increases length istrators felt more prepared, there were competing priorities to

of stay and is often more resource intensive in terms of health maintaining preparedness and the likelihood of an event was

care working staffing and supplies. One particularly concern- small; 82% of these administrators cited competing priorities

ing finding was that 41% of the hospitalized patients studied for funding and other resources, and 95% reported that com-

were believed to have acquired the disease through human- peting priorities (eg, increasing focus on active shooter threats

to-human transmission as a result of hospital exposures. This and/or desire to not focus on singular threats) reduced the focus

volume of health-care-associated cases is not wholly unex- on emerging infectious diseases, meaning that not sustaining

pected, based off of previous coronavirus outbreaks, but deeply infectious disease preparedness is a deliberate choice being

worrisome in that, again, it highlights the potential for hospi- made by hospital administrators. Because a majority of Ebola

tals to amplify disease transmission. preparedness was overseen by the IPC program and infection

preventionists, the decision to not invest in infectious disease

In response to these findings and the international efforts to preparedness can also be seen as a decision to not invest in the

stop the spread of the disease across dozens of countries, infec- public good, that is, IPC. Furthermore, only one-third of

tion prevention efforts must be prioritized. Hospitals are the respondents could report which tier their hospital fell into

front line for infectious disease response, and their ability to in the 2015-established special pathogens tiered hospital

identify, isolate, and inform public health of potential cases framework.13

is vital to halt transmission. Reinforcing and investing in

IPC efforts within hospitals in the United States and globally As hospitals in the United States struggle with shortages of

must happen to combat the outbreak. Unfortunately, to truly PPE and work to prepare for potential cases of COVID-19,

use IPC programs for COVID-19 response, it is important to it is critical that such efforts not only include IPC, but also seek

understand why health-care-associated outbreaks and infec- to invest in biopreparedness. Infection prevention is at the

tion prevention failures occur all too often. very nexus of biopreparedness in health care, and yet the

United States has continuously under-resourced and under-

Like most public health efforts, attention and resources tend to used this critical resource. This outbreak should be seen as

flood IPC programs during emergent times. The more under- an opportunity to reinforce hospital preparedness through

lying and systemic issue, though, is that IPC programs are fight- not only staffing, resources, and surge capacity, but also IPC

ing several roadblocks to better strengthen their hospitals’ efforts. In the future, when we evaluate our response to

preparedness for infectious disease threats. First, these pro- COVID-19 and look to invest in infectious disease readiness

grams are notoriously understaffed. A 2018 study by infection and health care preparedness, it is critical that we do not

preventionists Barles et al. found that, when staffing needs neglect the role of infection prevention programs and the

were reviewed, an effective IPC program needed 1.0 full-time, value they bring to biodefense. IPC programs are at the nexus

2 Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Universitas Airlangga, on 21 Apr 2020 at 16:47:42, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.55

Infection Prevention Roadblocks in Health Care

of public health and health care, acting as sentinels for infec- interventions. Science. 2003;300(5627):1961-1966. doi: 10.1126/science.

tious disease threats and a source for tacit knowledge. 1086478.

5. Butt TS, Koutlakis-Barron I, AlJumaah S, et al. Infection control and pre-

Recognizing their potential and investing in their utilization

vention practices implemented to reduce transmission risk of Middle East

serve to combat poor investment in biopreparedness across respiratory syndrome – coronavirus in a tertiary care institution in Saudi

the health care industry while enhancing U.S. health security. Arabia. Am J Infect Control. 2016;44(5):605-611.

6. Oh M, Park W, Park S, et al. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

outbreak in the Republic of Korea, 2015. Osong Public Health Res Perspect.

About the Author 2015;6(4):269-278.

7. Moran Ki. 2015 MERS-CoV outbreak in Korea: hospital-to-hospital

HonorHealth, George Mason University, Fairfax, VA (Popescu). transmission. Epidemiol Health. 2015;epub:e2015033. doi: 10.4178/epih/

e2015033.

Correspondence and reprint requests to Saskia Popescu, 250 E. Dunlap Ave., 8. Kim J. Hospital at center of South Korea’s MERS suspends services:

Phoenix, AZ 85020 (e-mail: spopesc2@gmu.edu). seven new cases. Published June 13, 2015. https://www.reuters.com/

article/us-health-mers-southkorea/hospital-at-center-of-south-koreas-mers-

Conflict of Interest Statement suspends-services-seven-new-cases-idUSKBN0OT0XL20150614. Accessed

The author has no conflict of interest to declare. February 8, 2020.

9. Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized

patients with 2019 novel coronavirus-infected pneumonia in Wuhan,

REFERENCES China. JAMA. 2020;epub. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585.

10. Bartles R, Dickson A, Babade O. A systematic approach to quantifying

1. Morgan DJ, Braun B, Milstone AM, et al. Lessons learned from hospital infection prevention staffing and coverage needs. Am J Infect Control.

Ebola preparation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2015;36(6):627-631. 2018;46(5):487-491.

doi: 10.1017/ice.2015.61. 11. Parrillo SL. The burden of National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN)

2. World Health Organization. Summary of probable SARS cases with reporting on the infection preventionist. Am J Infect Control. 2015;

onset of illness from 1 November 2002 to 31 July 2003. Published 43(6):S17.

December 31, 2003. http://www.who.int/csr/sars/country/table2004_ 12. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Inspector

04_21/en/. Accessed February 2, 2020. General. Hospitals reported improved preparedness for emerging infec-

3. Low DE. SARS: Lessons From Toronto. National Center for tious diseases after the Ebola outbreak. Published October 16, 2018.

Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-06-15-00230.asp. Accessed February

Published 2004 (National Academy of Sciences). https://www.ncbi.nlm. 8, 2020.

nih.gov/books/NBK92467/. Accessed February 10, 2020. 13. Popescu S, Leach R. Identifying gaps in frontline healthcare facility high-

4. Riley S, Fraser C, Donnelly CA, et al. Transmission dynamics of consequence infectious disease preparedness. Health Secur. 2019;17:

the etiological agent of SARS in Hong Kong: impact of public health 117-123. doi: 10.1089/hs.2018.0098.

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness 3

Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. Universitas Airlangga, on 21 Apr 2020 at 16:47:42, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at

https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/dmp.2020.55

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1093)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Coronavirus Disease 2019 - COVID-19: April 2020Document76 pagesCoronavirus Disease 2019 - COVID-19: April 2020ASHWIN BALAJI RNo ratings yet

- What Is The Role of Covid19 To The New Normal in EducationDocument3 pagesWhat Is The Role of Covid19 To The New Normal in EducationSevein Psco Usn100% (1)

- Virology Respiratory VirusesDocument6 pagesVirology Respiratory VirusesHisham ChomanyNo ratings yet

- What Is Coronavirus? The Different Types of CoronavirusesDocument9 pagesWhat Is Coronavirus? The Different Types of Coronavirusesashley bendanaNo ratings yet

- COVID-19: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Complications and Investigational TherapeuticsDocument8 pagesCOVID-19: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Complications and Investigational TherapeuticsHeidiNo ratings yet

- Molecular Biology: Negative Negative NegativeDocument1 pageMolecular Biology: Negative Negative Negativeravi kumarNo ratings yet

- Socio-Economic and Environmental Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic in Pakistan - An Integrated AnalysisDocument18 pagesSocio-Economic and Environmental Impacts of COVID-19 Pandemic in Pakistan - An Integrated AnalysisShahzad MirzaNo ratings yet

- Speech Health: The New Normal After Pandemic Tittle: "Living Peace in The New Normal"Document2 pagesSpeech Health: The New Normal After Pandemic Tittle: "Living Peace in The New Normal"Nia GallaNo ratings yet

- Coronavirus Covid 19 Frequently Asked QuestionsDocument6 pagesCoronavirus Covid 19 Frequently Asked Questionsaf dNo ratings yet

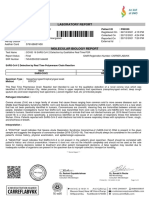

- Laboratory Report: Name: MR .Sandeep Mane Patient ID: P80359Document1 pageLaboratory Report: Name: MR .Sandeep Mane Patient ID: P80359akash srivastavaNo ratings yet

- CDT Alok Barik. Od-19-Sd-A-304-321. The Role of NCC in Covid-19Document3 pagesCDT Alok Barik. Od-19-Sd-A-304-321. The Role of NCC in Covid-19Ē Vì LNo ratings yet

- L51 - Home Collection KRL (Kolkata Reference Lab) Premises No - 031-0199 Plot No - CB 31/1 Street 199 Action Area 1C, KOLKATADocument3 pagesL51 - Home Collection KRL (Kolkata Reference Lab) Premises No - 031-0199 Plot No - CB 31/1 Street 199 Action Area 1C, KOLKATADebraj Das0% (1)

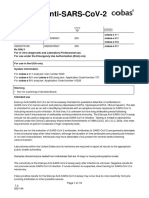

- EUA Roche Elecsys IfuDocument25 pagesEUA Roche Elecsys IfusaidaNo ratings yet

- Pfizer-Biontech COVID-19 Vaccine Briefing DocumentDocument92 pagesPfizer-Biontech COVID-19 Vaccine Briefing DocumentDavid CaplanNo ratings yet

- Peabody ParadoxDocument5 pagesPeabody ParadoxmorjdanaNo ratings yet

- MERS Coronavirus: Diagnostics, Epidemiology and TransmissionDocument21 pagesMERS Coronavirus: Diagnostics, Epidemiology and TransmissionramopavelNo ratings yet

- Ks Hospital, Hospital Road, Distt Mandi, Himachal Pradesh MANDI, 175001Document2 pagesKs Hospital, Hospital Road, Distt Mandi, Himachal Pradesh MANDI, 175001Anurag UniyalNo ratings yet

- Middle East Respiratory Syndrome - Corona Virus (Mers-Cov) : A Deadly KillerDocument8 pagesMiddle East Respiratory Syndrome - Corona Virus (Mers-Cov) : A Deadly Killerdydy_7193No ratings yet

- Dead Bodies PDFDocument24 pagesDead Bodies PDFRj Concepcion RrtNo ratings yet

- Long Term Complications and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 PatientsDocument5 pagesLong Term Complications and Rehabilitation of COVID-19 Patientsmathias kosasihNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 Vaccines Training Modules Final Version For Cascading PDFDocument216 pagesCOVID 19 Vaccines Training Modules Final Version For Cascading PDFHerbert OmindeNo ratings yet

- Time - 2 June 2014Document62 pagesTime - 2 June 2014jliller100% (1)

- 3390 3396 PDFDocument7 pages3390 3396 PDFXavier Alexandro Ríos SalinasNo ratings yet

- COVID-19 Workplace Guidelines: Employee'S Guide Workplace Safety and HealthDocument13 pagesCOVID-19 Workplace Guidelines: Employee'S Guide Workplace Safety and HealthRusty CompassNo ratings yet

- Síntomas Posteriores Al Alta y Necesidades de Rehabilitación en Sobrevivientes de La Infección Por COVIDDocument13 pagesSíntomas Posteriores Al Alta y Necesidades de Rehabilitación en Sobrevivientes de La Infección Por COVIDmatiasNo ratings yet

- MIOSHA Guidelines For Employers As People Return To WorkDocument36 pagesMIOSHA Guidelines For Employers As People Return To WorkWXYZ-TV Channel 7 DetroitNo ratings yet

- Report Text COVID-19Document1 pageReport Text COVID-19Baba NanaNo ratings yet

- COVID-19: Dr. Moe Yee Soe Assistant Lecturer Department of Microbiology UM1Document42 pagesCOVID-19: Dr. Moe Yee Soe Assistant Lecturer Department of Microbiology UM1Naing Lin SoeNo ratings yet

- Clinical - Alimentary TractDocument15 pagesClinical - Alimentary TractJohn PungañaNo ratings yet

- COVID 19 Impact On City and Region What S Next After LockdownDocument20 pagesCOVID 19 Impact On City and Region What S Next After LockdownKRBKab.Gresik 2021No ratings yet