Professional Documents

Culture Documents

2 - Age-Related Testosterone Depletion and The Development of Alzheimer Disease

2 - Age-Related Testosterone Depletion and The Development of Alzheimer Disease

Uploaded by

Dmn NmnOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

2 - Age-Related Testosterone Depletion and The Development of Alzheimer Disease

2 - Age-Related Testosterone Depletion and The Development of Alzheimer Disease

Uploaded by

Dmn NmnCopyright:

Available Formats

LETTERS

STUDENTJAMA), has functioned as a refreshing space for an ex- We believe that, with a little extra assistance, medical stu-

change of the ideas of future physicians. In these pages, stu- dents can and will be able to publish all types of articles in JAMA.

dents have considered spiritual assessment of patients, the global Since publication of our editorial, we have accepted 2 re-

HIV/AIDS pandemic, and their own experience of medical edu- search papers in which medical students are the first author.

cation. They have reflected on the nature of healing and spo- In addition, we have had a number of inquiries and submis-

ken to the issues at the core of caring for patients. sions from medical students, as well as inquiries about the medi-

The Editorial announcing the end of STUDENTJAMA ad- cal student elective in medical journalism.

dressed the emerging emphasis on evidence over opinion. To We ask Palmer and Martin to have patience and let the evi-

remove STUDENTJAMA from the journal in the interest of “in- dence prove which is the more beneficial method for medical

corporat[ing] high-quality articles” misses the function of the students to have a forum for their work.

section. Students, of course, will rarely publish research of the Catherine D. DeAngelis, MD, MPH

type and quality demanded by the pages of JAMA, but what stu- Editor-in-Chief

dents bring is as important. Students write and speak of the Phil B. Fontanarosa, MD

ideals of medicine, of their hope for the best patient care, of Executive Deputy Editor

their struggles to forge new identities as healers. And in the JAMA

process of exchanging ideas over the pages of JAMA, we be-

lieve that medical students offer our senior colleagues a chance

to reflect on their own work as a physician. RESEARCH LETTER

For a generation, JAMA saw these attributes as central to its

mission. Indeed, they align well with 3 of JAMA’s 9 objectives: Age-Related Testosterone Depletion

to foster responsible and balanced debate on issues that affect and the Development of Alzheimer Disease

medicine and health care, to anticipate important issues and

trends in medicine and health care, and to inform readers about To the Editor: Normal male aging is associated with declines

nonclinical aspects of medicine and public health, including in serum levels of the sex steroid hormone testosterone, which

the political, philosophic, ethical, legal, environmental, eco- contributes to a range of disorders including osteoporosis and

nomic, historical, and cultural.2 sarcopenia.1 Unknown is how this relationship applies to age-

Medical students will benefit from JAMA’s development of related disorders in the brain, an androgen-responsive tissue.

an elective in medical journalism and enriched manuscript re- We hypothesize that testosterone levels in the brain are de-

view for student research submissions. These enhancements pleted as a normal consequence of male aging and that low brain

are appropriate and important, but they in no way speak to the levels of testosterone increase the risk of developing Alzhei-

void left by removing a student section from JAMA. We regret mer disease (AD). Recent data suggest a correspondence be-

this decision. tween reduced serum levels of testosterone and the clinical di-

Brian Palmer, MD, MS, MPH agnosis of AD.2,3 However, it is unclear whether testosterone

pres@www.amsa.org depletion contributes to or results from the disease process. To

National President investigate this issue, testosterone and estradiol levels were ana-

American Medical Student Association lyzed in postmortem brain tissue of elderly men and com-

Reston, Va pared with their neuropathological diagnoses.

Yvette Martin Methods. Brain tissue from men who had provided in-

Chair, Organization of Student Representatives formed consent was collected at autopsy by repositories asso-

Association of American Medical Colleges

ciated with Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers at Univer-

Washington, DC

sity of Southern California; University of California, Irvine;

1. DeAngelis CD, Fontanarosa PB. JAMA and medical students: new opportuni- University of California, San Diego; and Duke University. Tis-

ties. JAMA. 2004;291:2872.

2. The key and critical objectives of JAMA. JAMA. 2004;292:36. sue was collected between 1997 and 2003, with postmortem

delay less than 8 hours (mean delay=4.6 hours). Subjects with

In Reply: We appreciate the recognition by Dr Palmer and Ms conditions associated with altered testosterone levels (eg, end-

Martin that our decision to incorporate articles by medical stu- stage renal disease, liver disease, alcoholism, and diabetes) were

dents into JAMA with those of all other authors addresses the excluded from the study. Included subjects satisfied 1 of the

“emerging emphasis on evidence over opinion.” However, our following neuropathological diagnoses: (1) neuropathologi-

encouraging submission of evidence-based manuscripts (as we cally normal (controls) (Braak stage 0-1 without evidence of

do evidence-based practice) from all authors does not elimi- other degenerative changes, and lacking a clinical history of

nate our continued interest in publishing well-thought-out opin- cognitive impairment; n=17), (2) AD (Braak stage 5-6 with neu-

ion articles. We encourage submission of such manuscripts from ropathological diagnosis of AD in the absence of other neuro-

any JAMA reader, including medical students, and will con- pathology; n = 19), and (3) mild neuropathological changes

tinue to publish special communications, commentaries, A Piece (Braak stage 2-3 in the absence of discrete neuropathology; n=9).

of My Mind, and poetry. No subjects were neuropathologically diagnosed with Braak stage

©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. (Reprinted) JAMA, September 22/29, 2004—Vol 292, No. 12 1431

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of St. Andrews Library User on 05/12/2015

LETTERS

(F=0.002, P=.97). We found that brain levels of testosterone

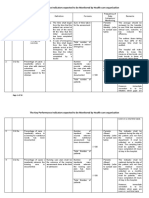

Figure 1. Brain Levels of Testosterone and Estradiol in Elderly Men

but not estradiol (FIGURE 2) are significantly lower in AD sub-

Testosterone Estradiol jects compared with the control subjects. We found that brain

levels of testosterone are also significantly reduced in men with

2.0

r = –0.71, P <.01

0.3

r = –0.04, P = .88

mild neuropathology consistent with early stage AD (Figure 2).

ng/g of Wet Tissue

Comment. Brain levels of testosterone significantly de-

1.5

0.2 crease with age in men who lack any evidence of neuropathol-

1.0 ogy, suggesting that neural androgen depletion is a normal con-

sequence of aging. In comparison with the control subjects, men

0.1

0.5 with AD exhibit significantly lower testosterone levels in the

brain. In contrast, the data suggest that estrogen levels in the

0 0 male brain are affected by neither advancing age nor AD diag-

50 60 70 80 90 100 50 60 70 80 90 100

nosis. Notably, testosterone depletion likely precedes and thus

Age, y Age, y

may contribute to rather than result from the development of

The estradiol comparison shows only 16 data markers as there are 2 subjects aged AD, since low brain testosterone is observed in men with early

70 years with the same estradiol value (0.06 ng).

indications of AD neuropathology. Although it remains pos-

sible that low testosterone may reflect an unmeasured corre-

Figure 2. Brain Levels of Testosterone and Estradiol in Men, by late of AD rather than be a contributing factor, we controlled

Neuropathological Diagnosis for established causes of low testosterone by our exclusion cri-

Testosterone Estradiol

teria and statistical adjustment. How testosterone depletion may

1.25 contribute to AD development is unknown. However, we have

recently reported that androgen depletion in male rodents in-

0.15

1.00 creases brain levels of -amyloid,5 the protein implicated as a

ng/g of Wet Tissue

causal factor in AD pathogenesis, and decreases neuronal sur-

0.75 0.10 vival upon exposure to toxic insult.6 Collectively, these find-

0.50

ings suggest that normal, age-related testosterone depletion in

0.05 the male brain may impair beneficial neural actions of andro-

0.25 gens and thereby act as a risk factor for the development of AD.

0 0

Emily R. Rosario, MS

Controls MNC AD Controls MNC AD Neuroscience Graduate Program

Left, Testosterone levels in age-matched control subjects (controls), subjects with

Lilly Chang, MD

mild neurological changes (MNC), and subjects with Alzheimer disease (AD). Right, Frank Z. Stanczyk, PhD

Estradiol levels in age-matched controls, subjects with MNC, and subjects with Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology

AD. For testosterone levels, P⬍.05 is the comparison of age-matched controls vs Keck School of Medicine

subjects with MNC and of age-matched controls vs subjects with AD by t test fol-

lowing analysis of covariance with age as a covariate. Error bars indicate SEM. Christian J. Pike, PhD

cjpike@usc.edu

Andrus Gerontology Center

4. Testosterone and estradiol levels were measured by radio- University of Southern California

immunoassay of homogenates of brain samples from the mid- Los Angeles

frontal gyrus following organic extraction and celite column

partition chromotography.4 Hormone levels expressed as hor- Funding/Support: This study was supported by a grant from the National Insti-

mone weight per wet tissue weight were statistically com- tute on Aging (AG14751 to Dr Pike). Tissue was obtained from the Alzheimer’s

Disease Research Centers at the University of Southern California AG05142, Uni-

pared using analysis of covariance with age as the covariate. versity of California Irvine AG16573, University of California San Diego AG05131,

This study was performed with institutional review board ap- and Duke University AG05128.

proval from the University of Southern California. 1. Morley JE. Androgens and aging. Maturitas. 2001;38:61-73.

Results. We observed that brain levels of testosterone but not 2. Hogervorst E, Lehmann DJ, Warden DR, McBroom J, Smith AD. Apolipopro-

tein E epsilon4 and testosterone interact in the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in men.

estradiol (FIGURE 1) were inversely correlated with age in men Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2002;17:938-940.

aged 50 to 97 years who were diagnosed as neuropathologically 3. Hogervorst E, Williams J, Budge M, Barnetson L, Combrinck M, Smith AD. Se-

normal. To investigate whether this depletion of brain testos- rum total testosterone is lower in men with Alzheimer’s disease. Neuroendocrinol

Lett. 2001;22:163-168.

terone may be a risk factor for the development of AD, we com- 4. Goebelsmann U, Bernstein GS, Gale JA, et al. Serum gonadotropin, testoster-

pared hormone levels among elderly men who exhibited no neu- one, estradiol, and estrone levels prior to and following bilateral vasectomy. In:

Lepow IH, Crozier R, eds. Vasectomy: Immunologic and Pathophysiologic Effects

ropathology, mild neuropathological changes, or moderate to in Animals and Man. New York, NY: Academic Press; 1979:165.

severe AD. Men in the 3 groups were of similar age, ranging from 5. Ramsden M, Nyborg AC, Murphy MP, et al. Androgens regulate beta-

amyloid levels in male rat brain. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1052-1055.

60 to 80 years with mean (SD) ages of 70.9 (5.3), 72.9 (5.7), 6. Ramsden M, Shin TM, Pike CJ. Androgens modulate neuronal vulnerability to

and 72.0 (6.5) years, respectively, using analysis of variance kainate lesion. Neuroscience. 2003;122:573-578.

1432 JAMA, September 22/29, 2004—Vol 292, No. 12 (Reprinted) ©2004 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: http://jama.jamanetwork.com/ by a University of St. Andrews Library User on 05/12/2015

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5819)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (845)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Jankovic, J. 2001 Tourette's Syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine 346.16 Pp.1184-1192Document9 pagesJankovic, J. 2001 Tourette's Syndrome. The New England Journal of Medicine 346.16 Pp.1184-1192Jesús Manuel CuevasNo ratings yet

- Actor Osce ImportantDocument124 pagesActor Osce Importantbabukancha67% (3)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Clinical Orthopaedic Examination-1 PDFDocument334 pagesClinical Orthopaedic Examination-1 PDFEmil Cotenescu100% (10)

- Full Download Test Bank For Medical Surgical Nursing in Canada 4th Edition Sharon L Lewis PDF Full ChapterDocument36 pagesFull Download Test Bank For Medical Surgical Nursing in Canada 4th Edition Sharon L Lewis PDF Full Chaptersaucisseserratedv8s97100% (23)

- Structured Clinical Management SCM For Personality Disorder An Implementation Guide Stuart Mitchell Editor Full Chapter PDF ScribdDocument68 pagesStructured Clinical Management SCM For Personality Disorder An Implementation Guide Stuart Mitchell Editor Full Chapter PDF Scribdwesley.ruehle633100% (6)

- Functional Results of Cataract Surgery in The Treatment of Phacomorphic GlaucomaDocument5 pagesFunctional Results of Cataract Surgery in The Treatment of Phacomorphic Glaucomachindy sulistyNo ratings yet

- The Caregiver Training CurriculumDocument10 pagesThe Caregiver Training CurriculumOlaya alghareniNo ratings yet

- G-J Tube SummaryDocument4 pagesG-J Tube SummaryStokleyCNo ratings yet

- Tocilizumab For Treatment Patients With COVID-19 - Recommended Medication For Novel Disease.Document8 pagesTocilizumab For Treatment Patients With COVID-19 - Recommended Medication For Novel Disease.Ginna Paola SaavedraNo ratings yet

- UtiDocument23 pagesUtiShamila KaruthuNo ratings yet

- Team 9 SOPD Follow Up Recommendation and Operation GuidelineDocument7 pagesTeam 9 SOPD Follow Up Recommendation and Operation GuidelineChris Jardine LiNo ratings yet

- Peds HemeImmune OUTLINEDocument10 pagesPeds HemeImmune OUTLINEAshleyNo ratings yet

- Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseDocument40 pagesChronic Obstructive Pulmonary DiseaseIVORY DIANE AMANCIONo ratings yet

- Journal OsteochondromaDocument14 pagesJournal OsteochondromaAnggi CalapiNo ratings yet

- LabadDocument8 pagesLabadAndriati RahayuNo ratings yet

- (Lecture 6) Vice, Drug Education and ControlDocument10 pages(Lecture 6) Vice, Drug Education and ControlJohnpatrick DejesusNo ratings yet

- Topic Subject Subtopic Delivery Activity Description Lab 2-ADocument1 pageTopic Subject Subtopic Delivery Activity Description Lab 2-ADoshi PriyalNo ratings yet

- Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation: College of Nursing Madras Medical CollegeDocument48 pagesCardiopulmonary Resuscitation: College of Nursing Madras Medical CollegeNithin ManlyNo ratings yet

- Childhood Leukaemias and Lymphomas: Chapter 89Document7 pagesChildhood Leukaemias and Lymphomas: Chapter 89RoppeNo ratings yet

- KPI - Foruth EditionDocument30 pagesKPI - Foruth EditionAnonymous qUra8Vr0SNo ratings yet

- SPS q1 Mod3 BIOMECHANICS Prevent InjuriesDocument14 pagesSPS q1 Mod3 BIOMECHANICS Prevent InjuriesRubenNo ratings yet

- ECOG/WHO/Zubrod Score (: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group WHO C. Gordon ZubrodDocument7 pagesECOG/WHO/Zubrod Score (: Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group WHO C. Gordon ZubrodsuehandikaNo ratings yet

- NZREX Clinical Handbook For Candidates 201 New ZealandDocument14 pagesNZREX Clinical Handbook For Candidates 201 New Zealandlaroya_31No ratings yet

- PT. Mersifarma TM - Pricelist & Link Produk E-Katalog 2023 - 2024Document6 pagesPT. Mersifarma TM - Pricelist & Link Produk E-Katalog 2023 - 2024pujiNo ratings yet

- Relational Processes and DSM-V Neuroscience, Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment (PDFDrive)Document294 pagesRelational Processes and DSM-V Neuroscience, Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment (PDFDrive)Matthew Christopher100% (5)

- EFG Healthcare - BrochureDocument2 pagesEFG Healthcare - BrochuremikewiesenNo ratings yet

- Odontomas: Pediatric Case Report and Review of The LiteratureDocument7 pagesOdontomas: Pediatric Case Report and Review of The LiteratureAlan PermanaNo ratings yet

- Prospectus Yuva Bharat Health PolicyDocument28 pagesProspectus Yuva Bharat Health PolicyS PNo ratings yet

- Artikel KKN Mandiri INGGIT GANARSIHDocument7 pagesArtikel KKN Mandiri INGGIT GANARSIHايو سمنNo ratings yet

- Bautista, Raphael Ephraime P. (Peh Lesson Plan)Document8 pagesBautista, Raphael Ephraime P. (Peh Lesson Plan)Raph BautistaNo ratings yet