Professional Documents

Culture Documents

GENDER - Trends of Feminist Historiography Modern India

GENDER - Trends of Feminist Historiography Modern India

Uploaded by

smrithi0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

110 views3 pagesOriginal Title

GENDER- Trends of feminist historiography Modern India.docx

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

110 views3 pagesGENDER - Trends of Feminist Historiography Modern India

GENDER - Trends of Feminist Historiography Modern India

Uploaded by

smrithiCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

GENDER HISTORY

ASSIGNMENT

Trends of Feminist Historiography, with special emphasis on India.

The task of feminist historiography is to understand the complex ways in which women are and

have been subjected too systematic subordination within a framework that acknowledges new

political possibilities for women and infusing them with new meanings. James Mill stated that

status of women indicated a society’s rung on the ladder of civilization, and India featured way

below. Most traditional and missionary writings viewed position of women in India as extreme

degradation and they saw their rule as making a significant improvement in the condition of

women. Traditional histories of nationalism have largely been written from a male perspective.

The trajectory of women’s historical accounts in colonial India started from the period of social

reforms in 19th ce. Though it was initiated by men, they made anxious debated around gender

questions but later women took over along with active involvement in freedom struggle.

Recasting women highlighted some of the historical processes which reconstitute patriarchy in

colonial India.

Nationalist history writing and reformist argued that reforms like social reform, education,

political participation led to emancipation of women from stagnating and also led to abolish

sati, female education, widow remarriage, rise age of consent, eradicate purdah etc. Gail

Pearson remarked women’s participation provided universalizing the national movement as a

whole. A group of later historian (leftist) along with feminist writing argued that all earlier

initiatives on women’s question were taken largely by men and reformers mostly belonged to

upper caste-middle class Hindu women. Geraldine Forbes remarks that women’s issues that did

not threaten patriarchal society could comfortably co-exist with nationalist movement.

Mrinalini Sinha’s work brought new aspects to studies on masculinity. Ashis Nady’s work

pointed that gender history would be incomplete without examining masculinity and how

colonial discourses saw Empire as masculine and India as feminine. He went on argue that

Gandhi subverted these notions by saying that feminine was worthier and preferred and

Gandhi gloried sacrifice to suffer, which he related with women. Therefore, he meant that

women had the ability to sacrifice and suffer.

Partha Chatterjee argues the growth of national movement, women’s question was co-opted

to larger political project and put on hold pending achievement of other objectives. His

formulations were largely true for Bengal. J.Devika contends that Partha’s model does not

apply to malayalee society. Anupama Rao looking at the anti-caste movement which was led by

Phule, her work shows when questions about women’s movement began to fade out

dominated by upper-caste then the question of social reform movement becomes important.

Subaltern historians sharpens the critique of colonial modernity. They also helped us achieve

that the reforms were very often based not on what women want but rather how to modernize

them. They also introduce categories like ‘White Subalternity’, pointing to gender and class

deviances and hierarchy.

Feminist Historians inclusive records the debates over social issues and political participation

denied women complex personalities and agency and continued to evoke gender stereotypes

also pointed out that liberation of India from British colonial rule did not do much for women’s

freedom. They also pointed out the reforms and nationalism told about the women’s desire and

emotions, their health and work etc remained untouched. A significant study had argued that

modern nationalist and liberal feminist historiographies have largely been Hindu centric and

have rendered Muslim women as invisible, oppressed and always sidelined. Reforms and

nationalism signal new opportunities for women and there was growing awareness of women’s

role and rights and their increase articulation in public-political spheres. Law against sati and

favor of widow remarriage was legally now permissible. Also spread of education among

women increased through print and political participation in public domain. Colonial law was

biased to colonial and reform discourse and law excluded large number of women often tribal,

working class.

Gender historians writes on recasting of patriarchy and it was subverting. Lata Mani argued

that contentious traditions around sati revealed that the indigenous participants conditioned

on colonial framework of debate which privileged Brahmanic tradition. Andrea Major’s show

the ideas of British on sati were not monolithic but a combination of revulsion and admiration.

Also helped in shaping even who opposed practice of sati culogised its ideals of devotion,

chastity and sacrifice construction of new and ideal women. In 1891 government raised the age

of consent for having sex with a wife from 10 to 12yrs. Conservatives who opposed this didn’t

want government restricting religious rituals such as garbhadhan as they believed that bill

would weaken the bonds of love between husbands and wives. Madan Mohan, articulated his

opposition to raising age of consent for marriage by citing the sanctions of sastras, some

women of All India Women Conference demanded ‘new sastras’. Paradoxical relationship

between reforms and gender well represented in case of female infanticide which was

increased because of state’s nature of economic policies which led to son preference and

daughters as unwanted burdens. Ranajit Guha, Subaltern historian provides extraordinary

detail about caste, class and kinship structures against a failed abortion resulting in death of a

peasant women. Widow Remarriage Act of 1856 administrated by Brahmin lawyers and

Victorian judges who tended to dive out customary law which became a means also to control

widow’s sexuality. Debate on it was linked to hardening of Hindu religious identities. Education

for women was linked to religious edifices. J.Devika shows differences between kind of

education advocated to Malayala Brahmin women and men, women received education that

was modern domesticity and prepare them to be efficient housewives and god companion.

Feminist historiography aims to produce not just new historical subject but a critique of gender-

neutral but gender-blind, methodologies of discipline itself and feminist critique of

historiography of colonial India has been strongest. Feminist scholars have not only pointed

how caste was consistently but also how sexuality, marriage and family took on different

contours in lower-caste, anti-Brahmin or Dalit politics of colonial period. Caste emerged central

in the work of many feminist historians. Prem Chowdhry shows contradictory stances of

government, where even while legally sanctioning inter-caste marriages, they morally or

ethnically denounced it. Anupama Rao brings out effects of social reform of gender by caste

radicals. She shows how Jyotirao Phule and Satyashodhak used same vocabulary to equate the

plight of women with that of lower castes.

Women’s organization like Women’s Indian Association, National Council of Women in India etc

emerged by 1920s they raised voices for suffrage, marriage and symbolized female solidarity.

Rennu Chakravarty’s memoir of women activist dead with patriarchal oppression. With

emergence of Gandhi women became more involved in mass struggles. Gandhi’s view on

women was mixed, he empowered women to join public action but believed they must stay

within domestic spheres. J.Devika states that Gandhian arguments that women had certain

natural qualities and a gentle power that made them worthy in political-public domain.

Feminist scholars have relied on oral histories and testimonies on Partition.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Gupta, Charu – Gendering Colonial India: Reforms, Print, Caste and

Communalism.

- Nair, J – On the question of Agency in Indian: Feminist Historiography.

- Class Notes.

-SMRITHI ANNA MATHEW

History (hons) 3rd yr

170316

You might also like

- Lazard Secondary Market Report 2022Document23 pagesLazard Secondary Market Report 2022Marcel LimNo ratings yet

- Transparent Glycerine Soap Bar With Bio-Terge 804 and Amphosol HCG #874Document2 pagesTransparent Glycerine Soap Bar With Bio-Terge 804 and Amphosol HCG #874NukiAdela100% (2)

- TM-1801 AVEVA Everything3D™ (2.1) Foundations Rev 3.0Document146 pagesTM-1801 AVEVA Everything3D™ (2.1) Foundations Rev 3.0Indra Rosadi100% (3)

- History of Doing Book ReviewDocument4 pagesHistory of Doing Book ReviewArchana Pawar100% (1)

- GENDER - Nationalist Resol of Women's Question Modern IndiaDocument3 pagesGENDER - Nationalist Resol of Women's Question Modern Indiasmrithi0% (1)

- Bhakti Among Women in Medieval IndiaDocument4 pagesBhakti Among Women in Medieval IndiaArshita KanodiaNo ratings yet

- Women SaintsDocument4 pagesWomen Saintspooja.r0829No ratings yet

- Historiographies On The Nature of The Mughal State: Colonialsist HistoriographyDocument3 pagesHistoriographies On The Nature of The Mughal State: Colonialsist Historiographyshah malikNo ratings yet

- Popular RightsDocument11 pagesPopular RightssmrithiNo ratings yet

- Modern India 2Document5 pagesModern India 2Abhinav PriyamNo ratings yet

- Women BhaktasDocument6 pagesWomen BhaktasRaahelNo ratings yet

- Nature of State of Early Medieval India PDFDocument7 pagesNature of State of Early Medieval India PDFNitu KundraNo ratings yet

- Indian Feudalism Debate AutosavedDocument26 pagesIndian Feudalism Debate AutosavedRajiv Shambhu100% (1)

- Aspects of Bhakti Movement in India: TH THDocument10 pagesAspects of Bhakti Movement in India: TH THchaudhurisNo ratings yet

- Historiography of Delhi SultanateDocument22 pagesHistoriography of Delhi SultanateKundanNo ratings yet

- Can The Revolt of 1857 Be Described As A Popular Uprising? CommentDocument5 pagesCan The Revolt of 1857 Be Described As A Popular Uprising? CommentshabditaNo ratings yet

- Early Medieval IndiaDocument10 pagesEarly Medieval IndiaAdarsh jha100% (1)

- Bhakti MovementDocument4 pagesBhakti MovementAnvesha VermaNo ratings yet

- 9 Historiography of Indian Nationalism PDFDocument12 pages9 Historiography of Indian Nationalism PDFAryan AryaNo ratings yet

- Rise of Rajputs and The Nature of StateDocument3 pagesRise of Rajputs and The Nature of StateSanchari DasNo ratings yet

- Monotheistic Movements in North IndiaDocument3 pagesMonotheistic Movements in North Indiaaryan jainNo ratings yet

- Evaluate The Role and Contributions of Martin Luther King JR To The Making and Strengthening of The Civil Rights Movement.Document3 pagesEvaluate The Role and Contributions of Martin Luther King JR To The Making and Strengthening of The Civil Rights Movement.Alivia BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- NATURE OF REVOLT OF 1857 by VARUN KUMARDocument9 pagesNATURE OF REVOLT OF 1857 by VARUN KUMARVarun PandeyNo ratings yet

- Bhakti TraditionDocument30 pagesBhakti TraditionPradyumna BawariNo ratings yet

- Feudalism DebateDocument10 pagesFeudalism DebateAshmit RoyNo ratings yet

- Origin of RajputsDocument11 pagesOrigin of Rajputskulbhushan100% (1)

- The Marathas Under The Peshwas HistoryDocument11 pagesThe Marathas Under The Peshwas HistoryShubham SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- (B) Taiping and Boxer Movements - Causes, Ideology, NatureDocument7 pages(B) Taiping and Boxer Movements - Causes, Ideology, Natureinsha moquitNo ratings yet

- Barani AssignmentDocument7 pagesBarani Assignmentakku UshaaNo ratings yet

- From The Lion Throne: Political and Social Dynamics of The Vijayanagara EmpireDocument36 pagesFrom The Lion Throne: Political and Social Dynamics of The Vijayanagara Empirearijeet.mandalNo ratings yet

- History Notes by e Tutoriar PDFDocument53 pagesHistory Notes by e Tutoriar PDFRohan GusainNo ratings yet

- VijayanagarDocument4 pagesVijayanagarpooja.r0829No ratings yet

- Different Schools of Thought #SPECTRUMDocument8 pagesDifferent Schools of Thought #SPECTRUMAditya ChourasiyaNo ratings yet

- Revenue System and Agricultural Economy During The Sultanate PeriodDocument17 pagesRevenue System and Agricultural Economy During The Sultanate PeriodIshaan ZaveriNo ratings yet

- HISTORIOGRAPHIESDocument3 pagesHISTORIOGRAPHIESShruti JainNo ratings yet

- Historiography On The Nature of Mughal StateDocument3 pagesHistoriography On The Nature of Mughal StateShivangi Kumari -Connecting Fashion With HistoryNo ratings yet

- MHI 06 Assignment IGNOUDocument6 pagesMHI 06 Assignment IGNOUAPA SKG100% (3)

- Medieval India History Reconstructing ResoourcesDocument9 pagesMedieval India History Reconstructing ResoourcesJoin Mohd ArbaazNo ratings yet

- Nayaka Syatem and Agrarian SetupDocument3 pagesNayaka Syatem and Agrarian SetupPragati SharmaNo ratings yet

- 18th Century As A Period of TransitionDocument5 pages18th Century As A Period of TransitionAshwini Rai0% (1)

- Popular Rights Movement in JapanDocument6 pagesPopular Rights Movement in JapanJikmik MoliaNo ratings yet

- Alaudin Khilji Market ReformsDocument11 pagesAlaudin Khilji Market ReformsArshita KanodiaNo ratings yet

- Indian Feudalism DebateDocument16 pagesIndian Feudalism DebateJintu ThresiaNo ratings yet

- 1911 RevolutionDocument8 pages1911 RevolutionKusum KumariNo ratings yet

- Trade in Early Medieval IndiaDocument3 pagesTrade in Early Medieval IndiaAshim Sarkar100% (1)

- Inter-Regional and Maritime TradeDocument24 pagesInter-Regional and Maritime TradeNIRAKAR PATRA100% (2)

- Irfan Habib-barani-Alauddin Khalaji Price Regulations-Ieshr1984Document22 pagesIrfan Habib-barani-Alauddin Khalaji Price Regulations-Ieshr1984armyk5991100% (1)

- Moderates and ExtremistsDocument3 pagesModerates and ExtremistsTanu 1839100% (1)

- Early Medieval Period A Distinctive PhasDocument3 pagesEarly Medieval Period A Distinctive Phasmama thakurNo ratings yet

- Communalism Between 1920 and 1947Document5 pagesCommunalism Between 1920 and 1947smrithi100% (2)

- Swadeshi and RadicalsDocument27 pagesSwadeshi and RadicalsAshishNo ratings yet

- Nature of The 1857 RevoltDocument3 pagesNature of The 1857 RevoltJyoti Kulkarni0% (1)

- Early Medieval IndiaDocument19 pagesEarly Medieval IndiaIndianhoshi HoshiNo ratings yet

- Debates Over 18th Century India Change V PDFDocument6 pagesDebates Over 18th Century India Change V PDFAbhishek Shivhare100% (1)

- Gender As A Category of Historical AnalysisDocument5 pagesGender As A Category of Historical AnalysisM.K.100% (1)

- Gender Historiography 2Document6 pagesGender Historiography 2maham sanayaNo ratings yet

- Unit 16 Early Medieval Urbanisation From Epigraphy and TextsDocument13 pagesUnit 16 Early Medieval Urbanisation From Epigraphy and TextsStanzin PhantokNo ratings yet

- VIJAYNAGARDocument5 pagesVIJAYNAGARSaima ShakilNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Early Mediaeval IndiaDocument7 pagesCharacteristics of Early Mediaeval Indiamama thakur100% (1)

- AK AssignmentDocument4 pagesAK AssignmentAkshatNo ratings yet

- Cholas - Theory On Nature of StateDocument8 pagesCholas - Theory On Nature of StateKundan100% (1)

- Women in The National MovementDocument6 pagesWomen in The National Movementshoan maneshNo ratings yet

- Historiography, Social ReformsDocument3 pagesHistoriography, Social ReformsNishita SindhuNo ratings yet

- Reforms in The Early Meiji Period (1868-1880)Document10 pagesReforms in The Early Meiji Period (1868-1880)smrithiNo ratings yet

- Japan-China Joint History Research Report ...Document10 pagesJapan-China Joint History Research Report ...Nick john CaminadeNo ratings yet

- GENDER - Trends of Feminist Historiography Modern IndiaDocument3 pagesGENDER - Trends of Feminist Historiography Modern IndiasmrithiNo ratings yet

- Background - : Illinois, Which Held That The Grain Warehouses Were A, "Private Utility in The Public Interest"Document7 pagesBackground - : Illinois, Which Held That The Grain Warehouses Were A, "Private Utility in The Public Interest"smrithiNo ratings yet

- March 1st Turning PointDocument8 pagesMarch 1st Turning Pointsmrithi100% (2)

- Final Paper: ASIA 519 History of Japanese International Relations and Foreign PolicyDocument9 pagesFinal Paper: ASIA 519 History of Japanese International Relations and Foreign PolicysmrithiNo ratings yet

- Japanese Industrialization and Economic GrowthDocument5 pagesJapanese Industrialization and Economic GrowthsmrithiNo ratings yet

- Lit, Pop Culture & GenderDocument2 pagesLit, Pop Culture & GendersmrithiNo ratings yet

- Neo-Confucianism & Nature of Yangban SocietyDocument5 pagesNeo-Confucianism & Nature of Yangban SocietysmrithiNo ratings yet

- Civil Disobedience MovementDocument15 pagesCivil Disobedience Movementsmrithi100% (1)

- Japanese ImperialismDocument15 pagesJapanese Imperialismsmrithi100% (2)

- Popular RightsDocument11 pagesPopular RightssmrithiNo ratings yet

- Meiji EconomyDocument10 pagesMeiji EconomysmrithiNo ratings yet

- Meiji Constitution PDFDocument5 pagesMeiji Constitution PDFsmrithiNo ratings yet

- FEMINISMDocument2 pagesFEMINISMsmrithiNo ratings yet

- Ambedkar - View On Dalit Movt.Document4 pagesAmbedkar - View On Dalit Movt.smrithiNo ratings yet

- Lit, Pop Culture & GenderDocument2 pagesLit, Pop Culture & GendersmrithiNo ratings yet

- GENDER - Nationalist Resol of Women's Question Modern IndiaDocument3 pagesGENDER - Nationalist Resol of Women's Question Modern Indiasmrithi0% (1)

- Formation - INC - AO HUME & LORD DUFFERIN..Document9 pagesFormation - INC - AO HUME & LORD DUFFERIN..smrithi100% (1)

- Constitution-Making in IndiaDocument9 pagesConstitution-Making in IndiasmrithiNo ratings yet

- Communalism Between 1920 and 1947Document5 pagesCommunalism Between 1920 and 1947smrithi100% (2)

- Communalism: Rise and Growth: Myth Ours Is A Five-Thousand-Year-Old Hindu Nation! FactDocument14 pagesCommunalism: Rise and Growth: Myth Ours Is A Five-Thousand-Year-Old Hindu Nation! FactsmrithiNo ratings yet

- Position of Women in MIDocument4 pagesPosition of Women in MIsmrithiNo ratings yet

- Gender Position of Women in MiDocument38 pagesGender Position of Women in MismrithiNo ratings yet

- International Labor and Working-Class, Inc., Cambridge University Press International Labor and Working-Class HistoryDocument29 pagesInternational Labor and Working-Class, Inc., Cambridge University Press International Labor and Working-Class HistorysmrithiNo ratings yet

- Discussion Problems: FAR Ocampo/Cabarles/Soliman/Ocampo FAR.2902-Inventories OCTOBER 2020Document8 pagesDiscussion Problems: FAR Ocampo/Cabarles/Soliman/Ocampo FAR.2902-Inventories OCTOBER 2020music niNo ratings yet

- Platinum Tours v. Panililio (CivPro - Jurisdiction)Document3 pagesPlatinum Tours v. Panililio (CivPro - Jurisdiction)Cathy AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- Tax 1 Course Outline 2018-2019 Final RevisionDocument9 pagesTax 1 Course Outline 2018-2019 Final Revisionjorg100% (1)

- MR8MDocument6 pagesMR8MAna MacarroneNo ratings yet

- Sanjay Kishan Kaul C.J. (Oral)Document6 pagesSanjay Kishan Kaul C.J. (Oral)RAJESH KUMARNo ratings yet

- Newton's Law of Motion: Law of Interaction: Quarter 1: Week 2Document3 pagesNewton's Law of Motion: Law of Interaction: Quarter 1: Week 2Lougene CastroNo ratings yet

- 97 People Vs MamantakDocument2 pages97 People Vs MamantakMichaela PradesNo ratings yet

- 75 Questions Test - SolutionDocument65 pages75 Questions Test - SolutionCute BabiesNo ratings yet

- NCA Held For Sale Discontinued OperationsDocument15 pagesNCA Held For Sale Discontinued OperationsDog WatcherNo ratings yet

- Pol 214Document3 pagesPol 214JulianNo ratings yet

- Kirby - Marvel Appellate Document Record Volume 9Document291 pagesKirby - Marvel Appellate Document Record Volume 9Jeff TrexlerNo ratings yet

- Revue Des Études Juives. 1880. Volume 48.Document370 pagesRevue Des Études Juives. 1880. Volume 48.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et Orientalis100% (1)

- 07 - Chapter 2 PDFDocument58 pages07 - Chapter 2 PDFBalu Mahendra SusarlaNo ratings yet

- Gardaí Never Investigated State Official's Destruction of Documents, Trial HearsDocument444 pagesGardaí Never Investigated State Official's Destruction of Documents, Trial HearsRita Cahill100% (1)

- ToyWorks With Income Statement and Balance SheetDocument19 pagesToyWorks With Income Statement and Balance SheetMervin MalaranNo ratings yet

- Final Signed Opinion To CarmichaelDocument5 pagesFinal Signed Opinion To CarmichaelWSYX/WTTENo ratings yet

- Module 10 The Teaching ProfessionDocument18 pagesModule 10 The Teaching Professionlyrinx gNo ratings yet

- ECSDocument53 pagesECSApurva MeshramNo ratings yet

- ICAO-IMO JWG-SAR-28-WP.7 - Iridium GMDSS SAR Service Implementation (United States)Document9 pagesICAO-IMO JWG-SAR-28-WP.7 - Iridium GMDSS SAR Service Implementation (United States)Martin NiNo ratings yet

- Simple and General Annuities: LessonDocument18 pagesSimple and General Annuities: LessonLyka MercadoNo ratings yet

- Cyberratings Cloud Network Firewall ReportDocument16 pagesCyberratings Cloud Network Firewall ReportelochoNo ratings yet

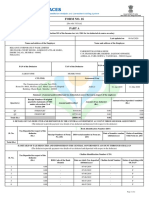

- Form No. 16: Part ADocument8 pagesForm No. 16: Part AParikshit ModiNo ratings yet

- BELLA 13716 1L Ice Cream Maker, Red IM PDFDocument30 pagesBELLA 13716 1L Ice Cream Maker, Red IM PDFMargoth C NovoaNo ratings yet

- Updated Syllabus OnlyDocument80 pagesUpdated Syllabus OnlySami NathanNo ratings yet

- 09-C-10076-1 Jamie Leigh Harley State Bar Lic SuspendedDocument2 pages09-C-10076-1 Jamie Leigh Harley State Bar Lic SuspendedJudgebustersNo ratings yet

- South Carolina Hunting RegulationsDocument48 pagesSouth Carolina Hunting RegulationsGeorge JonesNo ratings yet

- Click To Buy: The 2N4351 Is An Enhancement Mode N-Channel MosfetDocument1 pageClick To Buy: The 2N4351 Is An Enhancement Mode N-Channel Mosfetluismena09051982No ratings yet