Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Use of Medicinal Plants With Teratogenic and Abortive Effects by Pregnant Women in A City in Northeastern Brazil

Uploaded by

Iara PachêcoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Use of Medicinal Plants With Teratogenic and Abortive Effects by Pregnant Women in A City in Northeastern Brazil

Uploaded by

Iara PachêcoCopyright:

Available Formats

THIEME

Original Article 127

Use of Medicinal Plants with Teratogenic and

Abortive Effects by Pregnant Women in a City in

Northeastern Brazil

Uso de Plantas Medicinais com Efeitos Teratogênicos e

Abortivos por Gestantes em uma Cidade no Nordeste do

Brasil

Cristina Ruan Ferreira de Araújo1 Felipe Gomes Santiago2 Marcelo Italiano Peixoto2

José Olivandro Duarte de Oliveira2 Mayrla de Sousa Coutinho3

1 Tutorial EducationProgramGroup / Conexão de Saberes, Address for correspondence Cristina Ruan Ferreira de Araújo, MD,

Department of Health Sciences, Universidade Federal de Campina PhD, Department of Health Sciences, Universidade Federal de

Grande – UFCG, Campina Grande, PB, Brazil Campina Grande – UFCG, Av. Juvêncio Arruda, 795 – Bodocongó,

2 Medical School, UFCG, Campina Grande, PB, Brazil Campina Grande, PB, Brazil 58431-040

3 Undergraduate Nursing Course, UFCG, Campina Grande, PB, Brazil (e-mail: profcristinaruan@gmail.com).

Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 2016;38:127–131.

Abstract Purpose The purpose of this study is to verify the use of medicinal plants by pregnant

women treated at four Basic Health Units and at a public maternity facility in Brazil’s

northeast.

Methods This is a cross-sectional, quantitative study, performed between February

and April 2014. The subjects were 178 pregnant women, aged 18 to 42 years. To collect

data, a structured questionnaire with dichotomous and multiple choice questions was

used. To verify the correlation between the variables, Pearson’s chi-square test was

Keywords used.

► phytotherapy Results The study showed that 30.9% of the pregnant women used medicinal plants,

► pregnancy and boldo was the most cited (35.4%). All the plants utilized, except lemongrass, have

► medicinal plants toxic effects in pregnancy, according to Resolution SES/RJ N° 1757. There was no

► peumus boldus statistically significant correlation between social class and use of medicinal plants.

► foeniculum vulgare Conclusion The health of the study participants and their unborn children is at risk

► melissa officinalis due to the inappropriate use of medicinal plants.

Resumo Objetivo Verificar o perfil de uso de plantas medicinais por gestantes atendidas em

quatro Unidades Básicas de Saúde da Família e em uma maternidade pública da cidade

de Campina Grande – PB, na região Nordeste do Brasil.

Métodos Estudo transversal, quantitativo, desenvolvido no período de Fevereiro a

Abril de 2014. Foi incluída uma amostra com 178 gestantes com idade entre 18 e 42

anos. O instrumento de coleta foi um questionário estruturado com perguntas

received DOI http://dx.doi.org/ Copyright © 2016 by Thieme Publicações

August 18, 2015 10.1055/s-0036-1580714. Ltda, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

accepted ISSN 0100-7203.

December 1, 2015

published online

March 21, 2016

128 Use of Medicinal Plants with Teratogenic and Abortive Effects in Northeastern Brazil Araújo et al.

dicotômicas e de múltipla escolha. Para verificar a associação entre as variáveis

estudadas, utilizou-se o teste Qui-quadrado de Pearson.

Resultados Foi constatado que 30,9% das gestantes utilizavam plantas medicinais,

Palavras-chave sendo o boldo a mais citada (35,4%). Entre as plantas utilizadas com alta frequência

► fitorerapia pelas gestantes, todas, com exceção apenas da Erva-Cidreira (Melissa officinalis),

► gravidez apresentavam possíveis efeitos tóxicos para a gestação, segundo a Resolução SES/RJ N°

► plantas medicinais 1757. Ao comparar a classe social e o uso de plantas medicinais, não observou-se

► peumus boldus relação significante.

► foeniculum vulgare Conclusões A saúde das grávidas que fazem uso de plantas consideradas medicinais,

► melissa officinalis assim como a de seus filhos, sofrem riscos devido ao uso inadequado destas plantas.

Introduction contraindicating various medicinal plants on the basis of

scientific studies that revealed the hazards they represent for

Phytotherapy is defined as therapy based on the use of the baby, both during gestation and breastfeeding.

medicinal plants. The use of these plants for treatment, The objective of this study was to identify which medici-

cure, and prevention of diseases has mostly originated nal plants are used by pregnant women attending a Central

from popular knowledge derived from ancient cultures.1 Unit and four Basic Family Health Units in the city of Campina

This traditional knowledge of medicinal plants has been Grande in the northeast of Brazil.

used by the pharmaceutical industry, as there is enormous

potential for the discovery of new drugs.2

Methods

According to the declaration of Alma-Ata in 1978, the

World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes that 80% of the This cross-sectional study with a quantitative design was

population in developing countries - including Brazil - use developed at the Elpídio de Almeida Health Institute (ISEA)

traditional practices in their basic healthcare, and 85% use located in the central district, and in four Basic Family

medicinal plants, or preparations from them. Accordingly, it Health Units (UBSF) of the Malvinas borough (Malvinas I,

is the intention of the WHO to encourage the use of phyto- II, III, and IV), in Campina Grande - PB, from February to

therapy in basic healthcare.3 April 2014.

As the use of medicinal plants is based mostly on cultural A total of 178 pregnant women over 18 years of age

heritage and not in research on their effects, it is necessary to participated in the research, in any stage of pregnancy.

study how they are used by the populace. Knowledge ac- They attended the ISEA and Basic Family Health Units of

quired from cultural heritage can lead to the inappropriate the Malvinas borough, and gave informed consent, based on

use of plants, with adverse reactions in certain situations.4 the guidelines and regulatory standards for research involv-

Pregnant women may turn to this therapeutic option and ing human beings covered by the Resolution 196/96 of the

require special attention. Because many allopathic medicines National Health Council.

are teratogenic and are contraindicated during pregnancy, The research team used a structured questionnaire to

women may seek phytotherapy as alternative care.5 gather data.5 The first part consisted of questions regarding

Medicinal plants have a globally important role during demographic and socioeconomic status; the second part

pregnancy, birth, and the postpartum period. The use of included questions regarding general knowledge about me-

plants before and after delivery and during lactation has been dicinal plants; the third part questioned specific knowledge,

documented in various cultures. However, the majority of such as indications for use of certain plants, and the method

research focuses on the knowledge of these plants held by of preparation, among others. The plants cited by pregnant

male folk healers, shamans, or others, neglecting the knowl- women were compared with those in Resolution SES/RJ N°

edge possessed by women themselves.6 1757, which contraindicated the use of certain plants during

Nonetheless, studies indicate that some medicinal plants pregnancy.

have toxic, teratogenic, and abortive potential, because some The researchers used SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA) Ver-

active principles are able to cross the placental barrier and sion 17.0 to organize the database and for statistical analysis.

reach the fetus, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy. To verify the association between the variables studied (use

Studies performed with plants commonly used by the popu- of plants as a dependent variable and social class as an

lace, such as the babosa (Aloe spp. L.), peppermint (Mentha independent variable), we used Pearson’s non-parametric

piperita L), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.), and carqueja Chi-square test, with a significance level of p< 0.05 and a 95%

(Baccharistrimera (Less.) DC.), among others, are contraindi- confidence interval. The social classification of the popula-

cated in pregnant women.7 tion was based on the economic criteria of the Brazilian

The Secretary of Health of the State of Rio de Janeiro Association of Research Companies (Associação Brasileira de

published Resolution SES/RJ No. 1757 on February 18, 2008, Empresas de Pesquisa - ABEP).

RBGO Gynecology and Obstetrics Vol. 38 No. 3/2016

Use of Medicinal Plants with Teratogenic and Abortive Effects in Northeastern Brazil Araújo et al. 129

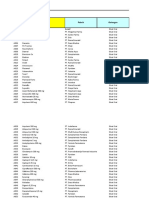

Table 1 Socioeconomic profile of pregnant women attending the Elpídio de Almeida Health Institute and the Basic Family Health

Units of the neighborhood of Malvina in Campina Grande, PB, Brazil, from February to April 2014

Characteristics n % Characteristics n %

Marital status Salary Range

Married 117 65.7 Up to 1 M.W. 91 51.1

Single 58 32.6 1 to 2 M.W. 64 36

Stable Relationship 2 1.1 2 to 3 M.W. 13 7.3

Divorced 1 0.6 More than 3 M.W. 10 5.6

Education Social Class

High School complete 79 44.4 C2 56 31.4

Elementary incomplete 45 25.3 C1 55 30.8

Elementary Complete 37 20.8 D 44 24.7

Higher education complete 9 5.1 B2 17 9.5

Illiterate 3 1.7 E 3 1.6

High School Incomplete 3 1.7 B1 3 1.6

Higher education Incomplete 2 1.1 – – –

Abbreviation: M.W., Minimum Wage.

The research project was approved by the Research Ethics The plants were acquired mostly by purchase (67.5%) or

Committee of the Hospital UniversitárioAlcidesCarneiro, were home-grown (19.5%), and were used typically once a

under protocol number 05552412.0.1001.5182 in 2013. day (36.6%), boiled (54.6%), and used daily (55.5%). Among

interviewees who used medicinal plants to treat discomfort

related to pregnancy (12.9%), the most common symptoms

Results

were nausea (47%), pain in general (29.4%), and heartburn

Of the 178 pregnant women interviewed, 48.8% were 26 to (11.8%).

35 years old. Their ages ranged from 18 to 42 years, with a A total 73.6% said they believed that the use of certain

mean age of 28. Among the participants, 65.7% were married medicinal plants can cause adverse effect in pregnancy.

and 44.4% had completed an elementary school education. Among those who said they perceived an undesirable effect

The predominant social class was C2 (31.4%), with a family (3.6%), the most frequently mentioned were bleeding (1.8%),

income of up to one minimum wage (51.1%). These data are allergy (0.9%), and headache (0.9%).

shown in ►Table 1. A total 47.2% were in the third trimester,

34.8% in the second, and 18% in the first. Conventional houses

Discussion

were occupied by 84.8%, and 80.3% had access to basic

sanitation. Pregnancy is considered special, both scientifically and

During pregnancy, 30.9% reported the use of medicinal culturally. Thus, certain practices based in both biomedical

plants. The most used plants were boldo (Peumusboldus and popular knowledge are seen in pregnant women.8 The

Molina, by 35.4%), Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare, by 24.2%), use of medicinal plants is one example.

balm mint (Melissa officinalis L., by 22.5%), lemongrass The concern about harm to the fetus leads some pregnant

(Cymbopogoncitratus (DC.) Stapf, by 6.4%), chamomile (Ma- women to avoid allopathic medicines and choose medicinal

tricariachamomilla L., by 4.8%), carqueja (B. trimera, by 3.2%), plants, which are perceived as natural and, therefore, unable

and mint (M. piperita, by 3.2%). The data for each of these to cause harm. This raises concerns about the possible effects

plants are summarized in ►Table 2. that their indiscriminate use may cause.9

There was no statistically significant correlation between In the present study, 30.9% of the pregnant women used

social class and the use of medicinal plants (p ¼ 0.8). Of the medicinal plants. In a study by Macena et al,10 55.5% of

women in the first trimester of pregnancy, 21.9% used pregnant women reported using medicinal plants.

medicinal plants, as did 33.9% in the second trimester, and We found no significant relationship (p ¼ 0.8) between

32.1% in the third trimester. the use of plants and social class. Therefore, the indiscrimi-

The participants reported that knowledge on the use of nate use of phytotherapy extends across all segments of the

medicinal plants had been acquired from relatives (89.3%), population, confirming studies by Veiga Júnior,11 which

friends (5.1%), books (2.2%), physicians (0.6%), and others highlight indiscriminate self-medication with medicinal

(1.7%). Relatives were the most responsible for the use of plants by all social classes.

plants (81.8%), while health professionals were responsible It is known that the first trimester of pregnancy is the

for only 2.6% of recommendations. period of embryonic differentiation. At this stage, there is

RBGO Gynecology and Obstetrics Vol. 38 No. 3/2016

130 Use of Medicinal Plants with Teratogenic and Abortive Effects in Northeastern Brazil Araújo et al.

Table 2 List of plants most used by pregnant women in this study

Popular name Scientific name % of use Indication Adverse Effects

Boldo Peumus boldus 35.4 Ability to protect the liver Teratogenic effects and

from toxins (hepatoprotec- abortifacient.18

tive) due to the antioxidant

activity of its active ingredi-

ent,15,16 boldine, which is also

an agent potentially useful in

the treatment of breast

cancer.17

Fennel Foeniculum vulgare 24.2 Carminative, expectorant, Hydroalcoholic extracts

spasmolytic, and diuretic caused effects on embryo im-

action.19 plantation. Teratogenic po-

tential should be

considered.20 Abortifacient

and galactogogue activity.21

Balm mint Melissa officinalis 22.5 Reduces the duration and in- Abortifacient or teratogenic

tensity of herpes outbreaks effects were not found in the

due to antiviral properties.22 literature consulted.

Sedative and anxiolytic

effects.23

Lemon Grass Cymbopogon citratus 6.4 Sedative, anti-inflammatory,24 Relaxing property for the

gastroprotective,25 and anti- uterine musculature.7

allergic action.26

Chamomile Matricaria chamomilla 4.8 Moderate antimicrobial and Has emmenagogue

antioxidant property and properties.28

powerful anti-inflammatory

activity.27

Carqueja Baccharis trimera 3.2 Cytoprotective of the gastric Induction of abortion due its

mucosa, capable of inhibiting uterotonic properties.7,33

ulcers.29 Has relevant hyper-

glycemic effect.30 Hepatopro-

tective, anti-inflammatory,

and cholagogue activity, re-

lated to the presence of

flavonoids.31,32

Mint Mentha piperita L. 3.2 It has shown promising activi- Emmenagogue and terato-

ty in the treatment of intesti- genic7; cytotoxic.35

nal spasms.34

greater risk of congenital malformations due to exposure to on home remedies considered beneficial, thereby facilitating

certain substances. In the present study, 21.9% of pregnant self-medication.13

women used medicinal plants in the first trimester, and their Self-medication is a practice in which a patient gets or

fetuses were, thus, more vulnerable to the risk of malforma- produces and uses a product, be it a synthetic drug or a

tions. During the second and third trimesters, changes due to medicinal plant, without the guidance of a qualified profes-

exposure to toxic substances may also occur, affecting sional. When used by pregnant women, such medication

growth and functional development.12 presents a risk to the health of both mother and fetus. One

The majority of the pregnant women (84.8%) lived in must emphasize the need for guidance by health professio-

conventional houses, which contributes to the use of nals (in this study, they were responsible for only 2.6% of

home-grown medicinal plants. phytotherapy recommendations), grounded in the scientific

The method by which women learned about the plants study of medicinal plants.12

was similar to that reported in the study by Veiga Junior11: The most consumed plant species were boldo(P. boldus)

90.1% of the interviewees obtained knowledge about such (35.4%), Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) (24.2%), balm mint (M.

therapy from family members or friends, and only 3.2% from officinalis) (22.5%), lemongrass (C. citratus) (6.4%), chamo-

a medical recommendation. These data confirm that the mile (M. chamomilla) (4.8%), carqueja(B. trimera) (3.2%), and

origin of knowledge on medicinal plants is mostly of socio- mint (Mentha piperita L.) (3.2%). In a study of the use of

cultural origin, rather than from prior studies on the effects medicinal plants by pregnant women,13 the most cited were

of such treatment.3 During pregnancy, women become more balm mint (79.5%), boldo (41%), and anise (28%). In the study

susceptible to advice and guidance from family and friends performed by Veiga Júnior,11 boldo was also the most cited

RBGO Gynecology and Obstetrics Vol. 38 No. 3/2016

Use of Medicinal Plants with Teratogenic and Abortive Effects in Northeastern Brazil Araújo et al. 131

plant (14.7%). In another study on the use of medicinal plants 16 Muñoz-Velázquez EE, Rivas-Díaz K, Loarca-Piña MGF, Mendoza-

by pregnant women, the most used were boldo (35.2%), Díaz S, Reynoso-Camacho R, Ramos-Gómez M. Comparacióndel-

lemongrass (21.5%), and mint (15.6%).10 contenido fenólico, capacidad antioxidante y actividadantiinfla-

matoria de infusionesherbalescomerciales. Rev Mex CiencAgríc.

In a comparison of the plants most used by pregnant women

2012;3(3):481–495

with those contraindicated during pregnancy, based on Resolu- 17 Paydar M, Kamalidehghan B, Wong YL, Wong WF, Looi CY, Mustafa

tion SES/RJ No. 175714, six of the seven most cited plants are MR. Evaluation of cytotoxic and chemotherapeutic properties of

listed. Thus, there is a clear need to establish safety criteria for the boldine in breast cancer using in vitro and in vivo models. Drug

use of medicinal plants during pregnancy. These criteria should Des DevelTher 2014;8:719–733

18 Almeida ER, Melo AM, Xavier H. Toxicological evaluation of the

take into account studies on the toxicity of phytotherapeutic

hydro-alcohol extract of the dry leaves of Peumus boldus and

products in pregnancy, including their actions on the fetus, and

boldine in rats. Phytother Res 2000;14(2):99–102

the possible adverse effects on the mother. 19 Araujo RO, Souza IA, Sena KXFR, Brondani DJ, Solidônio EG.

Avaliação biológica de Foeniculum vulgare (Mill.) (Umbelli-

ferae/Apiaceae). RevBras Plantas Med. 2013;15(2):257–263

20 Barilli SLS, Pereira MSL, Foscarini PT, Silva FC, Montanari T. An

References experimental investigation on effect of Foeniculum vulgare Mill.

1 Albuquerque UP, Hanazaki N. As pesquisas etnodirigidas na on gestation. Reprod Clim. 2012;27(2):73–78

descoberta de novos fármacos de interesse médico e farmacêu- 21 Newall CA, Anderson LA, Phillipson JD. Plantas medicinais: guia

tico: fragilidades e perspectivas. Rev Bras Farmacogn. 2006;16 para profissional de saúde. RibeirãoPreto: Editorial Premier; 2002

(Supl):678–689 22 Astani A, Navid MH, Schnitzler P. Attachment and penetration of

2 Sharma V, Sarkar IN. Bioinformatics opportunities for identifica- acyclovir-resistant herpes simplex virus are inhibited by Melissa

tion and study of medicinal plants. BriefBioinform 2013;14(2): officinalis extract. Phytother Res 2014;28(10):1547–1552

238–250 23 Kennedy DO, Little W, Scholey AB. Attenuation of laboratory-

3 da Rosa C, Câmara SG, Béria JU. Representations and use intention induced stress in humans after acute administration of Melissa

of phytotherapy in primary health care. CienSaudeColet 2011; officinalis (Lemon Balm). Psychosom Med 2004;66(4):607–613

16(1):311–318 24 Avoseh O, Oyedeji O, Rungqu P, Nkeh-Chungag B, Oyedeji A.

4 Bochner R, Fiszon JT, Assis MA, Avelar KES. Problemas associados Cymbopogon species; ethnopharmacology, phytochemistry and

ao uso de plantas medicinais comercializadas no Mercadão de the pharmacological importance. Molecules 2015;20(5):

Madureira, município do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. RevBras Plantas 7438–7453

Med. 2012;14(3):537–547 25 Sagradas J, Costa G, Figueirinha A, et al. Gastroprotective effect of

5 Faria PG, Ayres A, Alvim NAT. O diálogo com gestantes sobre Cymbopogoncitratus infusion on acute ethanol-induced gastric

plantas medicinais: contribuições para os cuidados básicos de lesions in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 2015;173:134–138

saúde. ActaSci Health Sci. 2004;26(2):287–294 26 Santos Serafim Machado M, Ferreira Silva HB, Rios R, et al. The

6 Lamxay V, de Boer HJ, Björk L. Traditions and plant use during anti-allergic activity of Cymbopogoncitratus is mediated via

pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum recovery by the Kry ethnic inhibition of nuclear factor kappa B (Nf-Kb) activation. BMC

group in Lao PDR. J EthnobiolEthnomed 2011;7:14 Complement Altern Med 2015;15:168–182

7 Alonso J. Tratado de fitomedicina: bases clínicas y farmacológicas. 27 McKay DL, Blumberg JB. A review of the bioactivity and potential

Buenos Aires: ISIS Ediciones SRL; 1998 health benefits of chamomile tea (Matricariarecutita L.). Phyt-

8 Calvasina PG, Nations MK, Jorge MSB, Sampaio HAC. “Birth other Res 2006;20(7):519–530

weakness”: cultural meanings of maternal impressions for infant 28 Arruda JT, Approbato FC, Maia MCS, Silva TM, Approbato MS.

health in Northeast Brazil. Cad SaudePublica 2007;23(2): Efeito do extrato aquoso de camomila (Chamomillarecutita L.) na

371–380 prenhez de ratas e no desenvolvimento dos filhotes. Rev Bras

9 Louik C, Gardiner P, Kelley K, Mitchell AA. Use of herbal treat- Plantas Med. 2013;15(1):66–71

ments in pregnancy. Am J ObstetGynecol 2010;202(5):439. 29 Gonzales E, Iglesias I, Carretero E, Villar A. Gastric cytoprotection

e1–439.e10 of bolivian medicinal plants. J Ethnopharmacol 2000;70(3):

10 Macena LM, Nascimento ASS, Krambeck K, Silva FA. Plantas 329–333

medicinais utilizadas por gestantes atendidas na unidade de 30 Oliveira AC, Endringer DC, Amorim LA, das Graças L Brandão M,

saúde da família (USF) do Bairro Cohab Tarumã no Município Coelho MM. Effect of the extracts and fractions of Baccharistri-

de Tangará da Serra, Mato Grosso. BioFar. 2012;7(1):143–155 mera and Syzygiumcumini on glycaemia of diabetic and non-

11 Veiga Junior VF. Estudo do consumo de plantas medicinais na diabetic mice. J Ethnopharmacol 2005;102(3):465–469

Região Centro-Norte do Estado do Rio de Janeiro: aceitação pelos 31 Alonso J, Desmarchelier C. Plantas medicinalesautóctonas de la

profissionais de saúde e modo de uso pela população. RevBras- Argentina. Bases científicas para suaplicaciónenatención pri-

Farmacogn. 2008;18(2):308–313 maria de salud. Buenos Aires: LOLA; 2006

12 Carmo TA, Nitrini SMOO. Drug prescription for pregnant women: 32 Pádua BdaC, Rossoni Júnior JV, Magalhães CL, et al. Protective

a pharmacoepidemiological study. CadSaude Publica 2004;20(4): effect of Baccharistrimera extract on acute hepatic injury in a

1004–1013 model of inflammation induced by acetaminophen. MediatorsIn-

13 Rangel M, Bragança FCR. Representações de gestantes sobre o uso flamm 2014;2014:196598

de plantas medicinais. RevBras Plantas Med. 2009;11(1):100–109 33 Ruiz ALTG, Taffarello D, Souza VHS, Carvalho JE. Farmacologia e

14 Rio de Janeiro. Secretaria de Estado de Saúde. Resolução SES/RJ n. toxicologia de Peumus boldus e Baccharisgenistelloides. Rev Bras

1757, de 18 de fevereiro de 2002. Contra-indica o uso de plantas Farmacogn. 2008;18(2):295–300

medicinais no âmbito do Estado do Rio de Janeiro e dá outras 34 Grigoleit HG, Grigoleit P. Peppermint oil in irritable bowel syn-

providências. Diário Oficial do Estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2002 Feb 20 drome. Phytomedicine 2005;12(8):601–606

15 Fernández J, Lagos P, Rivera P, Zamorano-Ponce E. Effectof boldo 35 Romero-Jiménez M, Campos-Sánchez J, Analla M, Muñoz-Serrano

(Peumus boldus Molina) infusiononlipoperoxidationinducedby- A, Alonso-Moraga A. Genotoxicity and anti-genotoxicity of some

cisplatin in miceliver. Phytother Res 2009;23(7):1024–1027 traditional medicinal herbs. Mutat Res 2005;585(1–2):147–155

RBGO Gynecology and Obstetrics Vol. 38 No. 3/2016

You might also like

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Thomas J. Flynn1987BVSDocument8 pagesThomas J. Flynn1987BVSIara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Preventive Veterinary Medicine: Cheryl Lans, Nancy Turner, Gerhard Brauer, Tonya KhanDocument6 pagesPreventive Veterinary Medicine: Cheryl Lans, Nancy Turner, Gerhard Brauer, Tonya KhanIara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- ismail2017WofS PDFDocument14 pagesismail2017WofS PDFIara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Accepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.04.007Document51 pagesAccepted Manuscript: 10.1016/j.fct.2016.04.007Iara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Suppression of Puerperal Lactation Using Jasmine Flowers (Jasminum Sambac)Document4 pagesSuppression of Puerperal Lactation Using Jasmine Flowers (Jasminum Sambac)Iara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Angel Josabad Alonso-CastroWofSDocument23 pagesAngel Josabad Alonso-CastroWofSIara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice: Mohammed S. Ali-Shtayeh, Rana M. Jamous, Rania M. JamousDocument10 pagesComplementary Therapies in Clinical Practice: Mohammed S. Ali-Shtayeh, Rana M. Jamous, Rania M. JamousIara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Pubmedmonteiro2001 PDFDocument9 pagesPubmedmonteiro2001 PDFIara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Effects of Annona Squamosa Extract On Early Pregnancy in RatsDocument6 pagesEffects of Annona Squamosa Extract On Early Pregnancy in RatsIara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- WofSM. NEHEZ 1992Document4 pagesWofSM. NEHEZ 1992Iara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- Author's Accepted Manuscript: Journal of EthnopharmacologyDocument52 pagesAuthor's Accepted Manuscript: Journal of EthnopharmacologyIara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Teratogenicity of Therapeutic Agents: Thomas H. Shepard, M.DDocument43 pagesTeratogenicity of Therapeutic Agents: Thomas H. Shepard, M.DIara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- Wof Syemele 2015Document18 pagesWof Syemele 2015Iara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Pharmacological and Toxicological Study of Maytenus Ilicifolia Leaf Extract. Part I - Preclinical StudiesDocument6 pagesPharmacological and Toxicological Study of Maytenus Ilicifolia Leaf Extract. Part I - Preclinical StudiesIara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- BVSLEUNG Kwok-Yin2002Document4 pagesBVSLEUNG Kwok-Yin2002Iara PachêcoNo ratings yet

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- PBL 2 Case PresentationDocument12 pagesPBL 2 Case PresentationRamish IrfanNo ratings yet

- Silage Sampling and AnalysisDocument5 pagesSilage Sampling and AnalysisG_ASantosNo ratings yet

- Celltac MEK 6500Document3 pagesCelltac MEK 6500RiduanNo ratings yet

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- MSDS of Poly Aluminum ChlorideDocument5 pagesMSDS of Poly Aluminum ChlorideGautamNo ratings yet

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Theories of Learning and Learning MetaphorsDocument4 pagesTheories of Learning and Learning MetaphorsTrisha Mei Nagal50% (2)

- Dif Stan 3-11-3Document31 pagesDif Stan 3-11-3Tariq RamzanNo ratings yet

- 15 UrinalysisDocument9 pages15 UrinalysisJaney Ceniza تNo ratings yet

- MCS120 220 Error Ref - GAA30082DAC - RefDocument21 pagesMCS120 220 Error Ref - GAA30082DAC - RefCoil98No ratings yet

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Qualitative Tests Organic NotesDocument5 pagesQualitative Tests Organic NotesAdorned. pearlNo ratings yet

- Allison Weech Final ResumeDocument1 pageAllison Weech Final Resumeapi-506177291No ratings yet

- OM Mannual FOsDocument38 pagesOM Mannual FOsAbdulmuqtadetr AhmadiNo ratings yet

- RCMaDocument18 pagesRCMaAnonymous ffje1rpaNo ratings yet

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Cross Rate and Merchant RateDocument26 pagesCross Rate and Merchant RateDivya NadarajanNo ratings yet

- Practice Test For Exam 3 Name: Miguel Vivas Score: - /10Document2 pagesPractice Test For Exam 3 Name: Miguel Vivas Score: - /10MIGUEL ANGELNo ratings yet

- Material: Safety Data SheetDocument3 pagesMaterial: Safety Data SheetMichael JoudalNo ratings yet

- Ethics, Privacy, and Security: Lesson 14Document16 pagesEthics, Privacy, and Security: Lesson 14Jennifer Ledesma-Pido100% (1)

- Data Obat VMedisDocument53 pagesData Obat VMedismica faradillaNo ratings yet

- Bi RadsDocument10 pagesBi RadsFeiky Herfandi100% (1)

- PL00002949Document5 pagesPL00002949Nino AlicNo ratings yet

- Thermit Welding (GB) LTD Process ManualsDocument10 pagesThermit Welding (GB) LTD Process ManualsAntónio AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Class 7 Work Book Answers Acid Bases and SaltsDocument2 pagesClass 7 Work Book Answers Acid Bases and SaltsGaurav SethiNo ratings yet

- Design and Details of Elevated Steel Tank PDFDocument10 pagesDesign and Details of Elevated Steel Tank PDFandysupaNo ratings yet

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Presentasi Evaluasi Manajemen Risiko - YLYDocument16 pagesPresentasi Evaluasi Manajemen Risiko - YLYOPERASIONALNo ratings yet

- 1 PolarographyDocument20 pages1 PolarographyRiya Das100% (1)

- Carbo Hi DratDocument11 pagesCarbo Hi DratILHAM BAGUS DARMA .NNo ratings yet

- Epoxy Data - AF35LVE TDS - ED4 - 11.17Document8 pagesEpoxy Data - AF35LVE TDS - ED4 - 11.17HARESH REDDYNo ratings yet

- PMEGP Revised Projects (Mfg. & Service) Vol 1Document260 pagesPMEGP Revised Projects (Mfg. & Service) Vol 1Santosh BasnetNo ratings yet

- Sociology/Marriage PresentationDocument31 pagesSociology/Marriage PresentationDoofSadNo ratings yet

- Starbucks Reconciliation Template & Instructions v20231 - tcm137-84960Document3 pagesStarbucks Reconciliation Template & Instructions v20231 - tcm137-84960spaljeni1411No ratings yet

- Child Case History FDocument6 pagesChild Case History FSubhas RoyNo ratings yet