Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Solving The Information Overload Problem: A Letter From Canada

Uploaded by

TNT1842Original Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Solving The Information Overload Problem: A Letter From Canada

Uploaded by

TNT1842Copyright:

Available Formats

ADOPTING BEST EVIDENCE IN PRACTICE SUPPLEMENT

Solving the information overload problem: a letter from Canada

David A Davis, Ileana Ciurea, Tanya M Flanagan, Laure Perrier

on behalf of the Ontario Guidelines Advisory Committee*

T HE GAP BETWEEN WHAT DOCTORS MIGHT DO (based on

evidence-based clinical practice guidelines [CPGs]) and ABSTRACT

what they actually do is wide, variable1 and growing. Many ■ Doctors are inundated with medical information, some

factors contribute to this situation. Doctors are inundated inadequately evidence-based, much of it captured in clinical

with The

new,Medical Journalevidence-based

often poorly of Australia ISSN:

and 0025-729X

sometimes15con- practice guidelines (CPGs).

March

flicting 2004 information.

clinical 180 6 68-71 This is particularly serious for

■ The Ontario Guidelines Advisory Committee (GAC) selects

©The Medical

the generalist, Journal

with overof Australia

400 0002004 www.mja.com.au

articles added to the

Adopting Best Evidence in Practice topic areas, searches for all CPGs on the topic, and reviews

biomedical literature each year. Adding further pressure to them using the AGREE Instrument.

the “gap” are workloads that have increased over the past

decade: doctors are seeing more patients with acute and ■ Based in large part on the AGREE score, the GAC

complex conditions.2 Canadian medical practitioners feel summarises one guideline in each topic area and mounts

that they are on a “medical treadmill”, working an average it on its website, with links to other information (eg, clinical

of 53.8 hours per week.3 Rural practitioners work even algorithms) where possible.

longer hours, offer more medical services and perform more ■ Two topic areas have been selected for implementation —

clinical procedures than their urban counterparts4 — thus the reduction of unnecessary preoperative testing and the

facing an even greater need for up-to-date information. rational management of acute low back pain.

Compounding this problem is another: there is good ■ Implementation strategies include performance feedback,

evidence that what we do in continuing medical education training of opinion leaders, development of algorithms and

(CME) (produce courses, give didactic lectures, mail unso- reminders, and communication through journals and

licited printed materials) is not very effective in changing continuing medical education activities.

physician behaviour.5-7 Interventions that do show promise

(such as reminders at the point of care, assistance of opinion MJA 2004; 180: S68–S71

leaders, academic detailing, feedback on performance) are

uncommon and not well used by policymakers, CME

providers and others. tors in their endeavours to practise high-quality care. Here

Thus, doctors are faced with many challenges to practis- we briefly describe the GAC’s evidence-based guideline

ing optimal care. There is too much, often conflicting, search, review and endorsement processes across the spec-

information that is not easily digestible, insufficiently evi- trum of clinical practice. We then focus on two specific

dence-based, and not delivered in a timely, effective or clinical areas to illustrate the type of work we do to promote

coordinated manner. To address some of these challenges, appropriate practice performance.

the Ontario Guidelines Advisory Committee (GAC) has

adopted a best-practice guideline strategy to support doc-

Solving the message problem: guideline search,

review, endorsement and synopsis

* Other members of the Ontario Guidelines Advisory

Committee: Dr Chris Cressey, MD, CM; Dr Thomas Faulds, Formed in 1997, the GAC is a joint body of the Ontario

MD, CCFP(EM); Dr William Feldman, MD, FRCPC; Dr Susan Medical Association and the Ontario Ministry of Health and

Fitzpatrick, PhD, FRACP; Dr Janet E Hux, MD, SM, FRCPC; Long-Term Care, with representation from the Institute for

Dr Walter W Rosser, MD, CCFP, FCFP; Ms Ann Marie Clinical Evaluative Sciences. A relatively small body, its

Strapp. mission is to implement as well as select and review CPGs.

Continuing Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of To fulfil its mission it has also added a long list of other

Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada. stakeholders in the dissemination of information and assess-

David A Davis, MD, CCFP, FCFP, Associate Dean; and Chair, Ontario ment of outcomes in the province, called the “Guideline

Guidelines Advisory Committee; Laure Perrier, MEd, MLIS, Information Collaborative”.

Specialist.

Guideline topics include a wide variety of primary-care

Ontario Guidelines Advisory Committee, Ontario Ministry of

topics generated by the committee members and by sections

Health and Long-Term Care and Ontario Medical Association,

within the Ontario Medical Association, as well as more

Toronto, ON, Canada.

Ileana Ciurea, MD, Implementation Coordinator; Tanya M Flanagan, MA,

specialised topics (eg, the appropriate use of echocardiogra-

Research Administrative Manager. phy, pelvic ultrasound and hyperbaric oxygen therapy).

Reprints will not be available from the authors. Correspondence: Dr David Once a clinical topic is identified, a systematic search of

A Davis, Continuing Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto, medical literature databases and Internet-based guideline

Suite 650, 500 University Avenue, Toronto, ON, Canada M5G 1V7. sites is conducted. Guidelines so identified are then sent to

Dave.davis@utoronto.ca trained physician reviewers throughout the province for peer

S68 MJA Vol 180 15 March 2004

SUPPLEMENT ADOPTING BEST EVIDENCE IN PRACTICE

Using these assessments, the GAC further reviews the

1: Partner organisations of the Ontario Medical

guidelines based on its medical expertise, its knowledge of

Association

the Ontario healthcare system and the recency of the

■ Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care guideline. The Committee then recommends the most

■ Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences timely, relevant and evidence-based CPGs for uptake by

■ Ontario College of Family Physicians doctors in Ontario. As at September 2003, GAC medical

■ Ontario Hospital Association reviewers had reviewed 448 individual guidelines, and 56

■ Continuing Education, Faculty of Health Sciences, McMaster best-practice guidelines had been endorsed.

University To help with the time challenges facing Ontario doctors,

■ Continuing Medical Education, Faculty of Health Sciences, the GAC summarises recommended CPGs into usable one-

Queen’s University

to two-page summaries (posted on the GAC website9 and

■ Continuing Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine, University

of Ottawa

featured monthly in the Ontario Medical Review, published

by the Ontario Medical Association). The GAC website also

■ Continuing Education, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto

provides electronic links to clinical decision tools, algo-

■ Continuing Medical Education, Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry,

University of Western Ontario rithms and patient educational materials, where they exist.

■ College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario

As an additional method of raising physician awareness of

■ Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada

GAC recommendations, the GAC showcases a tabletop

■ Workers’ Safety and Insurance Board of Ontario*

presentation of its work at many functions organised by the

■ Institute for Work and Health*

Ontario Medical Association and other partner organisa-

tions.

* Organisations identified as key to implementing guidelines on acute low

back pain only

Solving the message-delivery problem: an integrated

approach to implementing guidelines

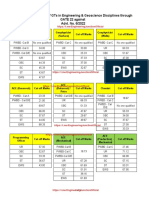

2: An integrated approach to implementing

guidelines* The GAC and its partner organisations (Box 1) have

undertaken a plan to implement best practice in two areas:

Importance of strategy† (a) preoperative testing, and (b) managing acute low back

Preoperative Managing acute pain. Both plans recognise that, although single guideline

Strategy testing low back pain education initiatives are most common, simple to plan and

Feedback on performance ♦♦‡ NA least expensive to implement, multiple, concurrent guide-

Enlisting support of opinion ♦ ♦

line implementation activities are more effective.6,10 The

leaders methods used in each of the two clinical areas are shown in

Coordinated CME approach ♦ ♦ Box 2.

Algorithms, reminders ♦♦ ♦♦

Peer assessment NA ♦ Preoperative testing

Patient education NA ♦♦ Routine preoperative electrocardiograms and chest x-rays

* Means of guideline dissemination include publication in the Ontario Medical

are commonly conducted despite little evidence of bene-

Review, posting on the Ontario Guidelines Advisory Committee website, and fit, 11 especially in low-risk patients and patients having

communication with partner organisations. low-risk procedures such as cataract surgery. The GAC has

† ♦♦ major emphasis; ♦ important intervention but not major focus. endorsed two preoperative testing guidelines that indicate

‡ Feedback to hospital administrators and key influentials.

CME = continuing medical education. NA = not applicable.

that routine preoperative testing provides no benefit to

patients and contributes to millions of wasted healthcare

dollars annually. 12,13

review, using a validated assessment tool, the AGREE Currently, the GAC is focused on implementing these

(Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation) instru- guidelines using a several-pronged approach involving feed-

ment.8 Currently, the GAC has a bank of over 50 trained back, opinion leaders, CME and a clinical algorithm.

doctors to assist in the guideline review process. Each Feedback: There is evidence that providing doctors with

guideline is assessed by a minimum of three reviewers; feedback on their individual performance compared with

guideline assessments are aggregated and given an “apple” that of a peer group is an effective means of changing

rating — four apples denoting an excellent guideline. The physician behaviour.14-16 Accordingly, the Institute for Clin-

review process allows for an evidence-based method to ical Evaluative Sciences reviewed the usage rates of preoper-

assess the quality of CPGs, identifies potential bias in the ative electrocardiograms and chest x-rays for selected high-

guideline development process and ensures that the recom- volume surgical procedures of low to intermediate risk.

mendations are both internally and externally valid. The Feedback profiles were mailed to hospitals in May 2003.

AGREE instrument is also useful in critically evaluating the The feedback data included hospital-specific usage rates for

methods used for developing the guidelines, the content of preoperative chest x-rays and electrocardiograms, hospital

the final recommendations, and the factors linked to their peer-group usage rates for preoperative chest x-rays and

uptake. electrocardiograms, and a hospital peer-group benchmark

MJA Vol 180 15 March 2004 S69

ADOPTING BEST EVIDENCE IN PRACTICE SUPPLEMENT

rate of testing. All data were handled in a secure environ- the plans has been moulded by practical and practice

ment under strict confidentiality provisions. realities, well beyond the scope of our project, and not easily

Opinion leaders: The GAC has trained doctors as opinion amenable to formal, objective evaluation. Third, the meas-

leaders — individuals who reside and work in a community, ures we intend to use to assess the impact of our efforts — a

and to whom people often turn for informal support or province-wide pre- and post-guideline-implementation data

advice.17 Opinion leaders include family physicians, anaes- analysis of hospital utilisation of routine preoperative elec-

thesiologists, hospital administrators and others. Following trocardiograms and chest x-rays and of lumbosacral spinal

their training, the GAC continues to support these individu- x-rays — have not yet been completed. Rates of change in

als throughout the province as they work towards changing the use of these tests will be used as a proxy to measure the

practice in their local communities. GAC’s success at implementing guidelines and changing

physicians’ behaviour, but we recognise that these are crude

Continuing medical education: The GAC is working measures, insensitive to many practice and practitioner

with the continuing education divisions of the five Ontario realities.

medical schools to implement the GAC-recommended pre- Nonetheless, through the work of the GAC, the Ontario

operative testing guidelines and other GAC-endorsed guide- Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care and the Ontario

lines into existing CME activities and events. Having Medical Association have demonstrated their commitment

established partnerships with the CME departments of the to the physicians of Ontario and to the endorsement of

five medical schools, the GAC aims to facilitate the provi- useful and provincially approved guidelines. Further,

sion of evidence-based preoperative testing guidance to all through its implementation planning and execution, the

physicians in Ontario through a consistent clinical message. Ontario Guideline Collaborative has engendered goodwill

Clinical algorithm: The GAC has developed and circu- and garnered support for an evidence-based guideline

lated to provincial hospitals an acceptable clinical algorithm endorsement and implementation program. Perhaps the

to function as a reminder — a tool of some importance in clearest sign of success is that the GAC and its collaborative

changing provider behaviour.18 efforts exist at all, aiming to improve the adoption of best

evidence by Ontario’s medical practitioners.

Managing acute low back pain

The key messages in caring for patients with acute low back Competing interests

pain — watch out for “red flags” denoting infection, None identified.

tumours and other comorbidities; encourage physical activ-

ity; minimise the use of painkillers and other medications;

avoid x-rays of the lumbosacral spine — are well known but References

not universally adopted as practice guidelines.19,20 Conse- 1. Bero LA, Grilli R, Grimshaw JM, et al. Closing the gap between research and

quently, the GAC has endorsed a CPG in this area.21 practice: an overview of systematic reviews of interventions to promote the

implementation of research findings. The Cochrane Effective Practice and

Furthermore, following a meeting of its key stakeholders Organization of Care Review Group. BMJ 1998; 317: 465-468.

and other bodies (the Workers’ Safety and Insurance Board, 2. Chan BTB. The declining comprehensiveness of primary care. CMAJ 2002; 166:

429-434.

the Institute for Work and Health), the GAC has endorsed

3. Martin S. More hours, more tired, more to do: results from the CMA’s 2002

(though not yet fully implemented) a coordinated imple- Physician Resource Questionnaire. CMAJ 2002; 167: 521-522.

mentation plan. The Committee borrows from the evidence 4. Slade S, Busing N. Weekly work hours and clinical activities of Canadian family

regarding effective continuing education and uses a multi- physicians: results of the 1997/98 National Family Physician Survey of the

College of Family Physicians of Canada. CMAJ 2002; 166: 1407-1411.

faceted approach. Among other interventions (Box 2), the 5. Davis D, O’Brien MA, Freemantle N, et al. Impact of formal continuing medical

CME divisions of the five medical schools and other provid- education: do conferences, workshops, rounds, and other traditional continuing

ers of CME, such as the Ontario College of Family Physi- education activities change physician behavior or health care outcomes? JAMA

1999; 282: 867-874.

cians, the Foundation for Medical Practice and the Royal 6. Davis DA, Thomson MA, Oxman AD, Haynes RB. Changing physician perform-

College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, will assist in ance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education

the deployment of large and small group CME events and strategies. JAMA 1995; 274: 700-705.

7. Oxman AD, Thomson MA, Davis DA, Haynes RB. No magic bullets: a systematic

activities. review of 102 trials of interventions to improve professional practice. CMAJ 1995;

153: 1423-1431.

8. The AGREE Collaboration. Appraisal of Guidelines Research and Evaluation.

Evaluating the effectiveness of the GAC guideline Available at: www.agreecollaboration.org (accessed Feb 2004).

9. Ontario Medical Assocation and Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care.

implementation process GAC: Guidelines Advisory Committee. Recommended clinical practice guide-

lines. Available at: www.gacguidelines.ca (accessed Feb 2004).

In making any evaluative comments about the GAC process

10. Mazmanian PE, Davis DA. Continuing medical education and the physician as a

and plans, it is necessary to be cautious about interpreting learner: guide to the evidence. JAMA 2002; 288: 1057-1060.

the impact of the project. First, the manner in which 11. Munro J, Booth A, Nicholl J. Routine preoperative testing: a systematic review of

the evidence. Health Technol Assess 1997; 1: i-iv, 1-62.

guideline review and endorsement is undertaken is imper-

12. Eagle KA, Chair. ACC/AHA Guideline update on perioperative cardiovascular

fect, including the application of the AGREE instrument. evaluation for noncardiac surgery. A report of the American College of Cardiol-

Second, the research on which the guideline implementa- ogy/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee

to Update the 1996 Guidelines on Perioperative Cardiovascular Evaluation for

tion and endorsement strategies is based is imperfect at Noncardiac Surgery). 2002. Available at: www.americanheart.org/downloadable/

best,22 and the way in which we have been able to roll out heart/1013454973885perio_update.pdf (accessed Feb 2004).

S70 MJA Vol 180 15 March 2004

SUPPLEMENT ADOPTING BEST EVIDENCE IN PRACTICE

13. Gander, L. Selective chest radiography: guidelines review. Prepared for the 17. Stross JK. The educationally influential physician. Journal of Continuing Medical

Health Services Utilization and Research Commission, Saskatchewan. Education in the Health Professions 1996; 16: 167-172.

2 0 0 0 . A v a i l a b l e a t : w w w. h s u r c . s k . c a / r e s o u r c e _ c e n t r e / c l i n i c a l / 18. Stone TT, Kivlahan CH, Cox KR. Evaluation of physician preferences for guideline

Chest%20radiography%20guideline%20review.pdf (accessed Feb 2004). implementation. Am J Med Qual 1999; 14: 170-177.

14. Kiefe CI, Allison JJ, Williams OD, et al. Improving quality improvement using 19. Atlas SJ, Deyo RA. Evaluating and managing acute low back pain in the primary

achievable benchmarks for physician feedback: a randomized controlled trial. care setting. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 120-131.

JAMA 2001; 285: 2871-2879. 20. Patel AT, Ogle AA. Diagnosis and management of acute low back pain. Am Fam

15. Jamtvedt G, Young JM, Kristoffersen DT, et al. Audit and feedback: effects on Physician 2000; 61: 1779-1786, 1789-1790.

professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 21. Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Low back pain, adult. 2003. Available at:

2003; (3): CD000259. www.icsi.org/knowledge/detail.asp?catID=29&itemID=149 (accessed Feb 2004).

16. Thomson O’Brien MA, Oxman AD, et al. Audit and feedback versus alternative 22. Grimshaw J, Campbell M, Eccles M, Steen N. Experimental and quasi-experi-

strategies: effects on professional practice and health care outcomes. Cochrane mental designs for evaluating guideline implementation strategies. Fam Pract

Database Syst Rev 2000; (2): CD000260. 2000; 17 Suppl 1: S11-S16. ❏

MJA Vol 180 15 March 2004 S71

You might also like

- Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeFrom EverandNursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Nursing Administration: Scope and Standards of PracticeFrom EverandNursing Administration: Scope and Standards of PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (3)

- Primary Urgent Care Guidelines UtiDocument22 pagesPrimary Urgent Care Guidelines UtiUti Nilam SariNo ratings yet

- Rheumatology Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, 2nd EditionFrom EverandRheumatology Nursing: Scope and Standards of Practice, 2nd EditionNo ratings yet

- 2206 Asthma Guideline and Supplement - FINAL 20071Document122 pages2206 Asthma Guideline and Supplement - FINAL 20071Extremadamente LindoNo ratings yet

- Early Childhood PDFDocument73 pagesEarly Childhood PDFThioNo ratings yet

- Ghid Anestezie Locala PDFDocument19 pagesGhid Anestezie Locala PDFanaNo ratings yet

- Ch01 Medical Surgical NursingDocument8 pagesCh01 Medical Surgical Nursingmicky1121100% (1)

- Clinical Guidlines and Clinical PathwaysDocument32 pagesClinical Guidlines and Clinical PathwaysAmbreen Tariq100% (1)

- Cs Ict1112 Ictpt Ia B 3Document1 pageCs Ict1112 Ictpt Ia B 3billy jane ramosNo ratings yet

- JCI Whitepaper Cpgs Closing The GapDocument12 pagesJCI Whitepaper Cpgs Closing The GapMathilda UllyNo ratings yet

- Empowerment Technologies 2nd Quarter ExaminationDocument5 pagesEmpowerment Technologies 2nd Quarter ExaminationJoylass P. Carbungco90% (31)

- Clinical Research Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeFrom EverandClinical Research Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Gui322cpg1504e2 PDFDocument15 pagesGui322cpg1504e2 PDFieo100% (1)

- Postoperative Management in AdultsDocument58 pagesPostoperative Management in AdultsAjay KumarNo ratings yet

- Ghid de OsteoporozaDocument55 pagesGhid de OsteoporozaMarius Creanga100% (1)

- Standards For Maternal and Neonatal Care - WHODocument72 pagesStandards For Maternal and Neonatal Care - WHODharmendra PanwarNo ratings yet

- 1-S2.0-S1939865422000315-MainDocument8 pages1-S2.0-S1939865422000315-MainnersrosdianaNo ratings yet

- Guia para El Diagnostico Manejo y Tratamiento Del HipertiroidismoDocument65 pagesGuia para El Diagnostico Manejo y Tratamiento Del HipertiroidismoAlma Vega MendivilNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practice Guidelines On Prostate Cancer: A Critical AppraisalDocument6 pagesClinical Practice Guidelines On Prostate Cancer: A Critical AppraisalJufrialdy AldyNo ratings yet

- 3rd Molar Guidelines April 2021Document110 pages3rd Molar Guidelines April 2021Nelson Ascencio NataleNo ratings yet

- 3rd Molar Guidelines April 2021 v3Document110 pages3rd Molar Guidelines April 2021 v3aram meyedyNo ratings yet

- Nationaln Tle: National Audit of Continence Care: Laying The FoundationDocument23 pagesNationaln Tle: National Audit of Continence Care: Laying The Foundationi can always make u smile :DNo ratings yet

- Perit Dial Int 2011 Blake 218 39Document22 pagesPerit Dial Int 2011 Blake 218 39Ika AgustinNo ratings yet

- JURNALDocument12 pagesJURNALAsMiraaaaNo ratings yet

- Evidence Selection, Appraisal, and PresentationDocument3 pagesEvidence Selection, Appraisal, and PresentationKisses'd Hershey'sNo ratings yet

- A Maternal and Child's Nurses Quest Towards ExcellenceDocument78 pagesA Maternal and Child's Nurses Quest Towards Excellencedecsag06No ratings yet

- What Is A Clinical Pathway? Development of A Definition To Inform The DebateDocument4 pagesWhat Is A Clinical Pathway? Development of A Definition To Inform The DebateRSIA MOELIANo ratings yet

- Clinical Algorithms To Aid Osteoarthritis Guideline DisseminationDocument13 pagesClinical Algorithms To Aid Osteoarthritis Guideline Disseminationfidatahir93No ratings yet

- ICU Report ENDocument36 pagesICU Report ENEmilio AcostaNo ratings yet

- 10 1097@aln 0b013e31823c1067Document17 pages10 1097@aln 0b013e31823c1067R Anrico MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Cancer - 2016 - Haugen - 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines For Adult Patients With Thyroid NodulesDocument10 pagesCancer - 2016 - Haugen - 2015 American Thyroid Association Management Guidelines For Adult Patients With Thyroid NodulesZuriNo ratings yet

- 2016 - Optimal Perioperative Management of The Geriatric PatientDocument18 pages2016 - Optimal Perioperative Management of The Geriatric PatientruthchristinawibowoNo ratings yet

- The Status of Accreditation in Primary CareDocument9 pagesThe Status of Accreditation in Primary CareSusi DesmaryaniNo ratings yet

- EDPerformanceMeasures ConsensusStatementDocument10 pagesEDPerformanceMeasures ConsensusStatementMarwa El SayedNo ratings yet

- Standards For General Practices: 4th EditionDocument160 pagesStandards For General Practices: 4th EditionJesse Lucas TamblynNo ratings yet

- Applying Lean Principles To Reduce Wait Times in A VA Emergency DepartmentDocument10 pagesApplying Lean Principles To Reduce Wait Times in A VA Emergency DepartmentNida KhoiriahNo ratings yet

- 04 Momoi 2012 Clinical Guidelines For Treating Caries in Adults JouDen40 - 95Document31 pages04 Momoi 2012 Clinical Guidelines For Treating Caries in Adults JouDen40 - 95Cherif100% (1)

- Practice Advisory For Preanesthesia EvaluationDocument17 pagesPractice Advisory For Preanesthesia EvaluationAdrian WirahamediNo ratings yet

- ISCCM Intensivist GuidelinesDocument28 pagesISCCM Intensivist GuidelinesEsther RaniNo ratings yet

- The Guideline For Standing SCI Mascip FinalDocument30 pagesThe Guideline For Standing SCI Mascip FinalJavierSanMartínHerreraNo ratings yet

- Joint Commission Research PaperDocument8 pagesJoint Commission Research Paperuzypvhhkf100% (1)

- SOGC - Endometriosis Diagnosis and ManagementDocument36 pagesSOGC - Endometriosis Diagnosis and ManagementreioctabianoNo ratings yet

- Ieras Guideline March 2014-TorontoDocument30 pagesIeras Guideline March 2014-Torontoasm obginNo ratings yet

- Pre-And Postoperative Management Techniques. Before and After. Part 1: Medical MorbiditiesDocument6 pagesPre-And Postoperative Management Techniques. Before and After. Part 1: Medical MorbiditiesMostafa FayadNo ratings yet

- IFOMPT Examination Cervical Spine Doc September 2012 DefinitiveDocument37 pagesIFOMPT Examination Cervical Spine Doc September 2012 DefinitiveMichel BakkerNo ratings yet

- Criteria For MRI of The Lumbar Spine.Document8 pagesCriteria For MRI of The Lumbar Spine.Eugene MagonovNo ratings yet

- Primary Dysmenorrhea ConsensusDocument11 pagesPrimary Dysmenorrhea ConsensusNorman AjxNo ratings yet

- Sepsis GuidelinesDocument3 pagesSepsis GuidelinesmgolobNo ratings yet

- Review of The NICE Guidelines For Multiple Myeloma: G. Pratt, T.C. MorrisDocument11 pagesReview of The NICE Guidelines For Multiple Myeloma: G. Pratt, T.C. MorrisHashim AhmadNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For The Management of Pregnant Women With Obesity: A Systematic ReviewDocument14 pagesGuidelines For The Management of Pregnant Women With Obesity: A Systematic ReviewMichael ThomasNo ratings yet

- 11 Optimizing The Management 1598065529Document12 pages11 Optimizing The Management 1598065529César ArveláezNo ratings yet

- Tasc Document: Lars Norgren and William R HiattDocument258 pagesTasc Document: Lars Norgren and William R HiatthgoldmanNo ratings yet

- Clinical Practice Guideline: Gastric Tube Placement VerificationDocument11 pagesClinical Practice Guideline: Gastric Tube Placement VerificationA'Gitto PurnawanNo ratings yet

- Eip Gpe Eqc 2003 1Document24 pagesEip Gpe Eqc 2003 1rhuNo ratings yet

- Article ContentDocument10 pagesArticle ContentRicardo Muñoz PérezNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Nursing - 2020 - Muinga - Designing Paper Based Records To Improve The Quality of Nursing DocumentationDocument16 pagesJournal of Clinical Nursing - 2020 - Muinga - Designing Paper Based Records To Improve The Quality of Nursing DocumentationrindaNo ratings yet

- PQMD HSS Medical Mission Guidelines 2019Document24 pagesPQMD HSS Medical Mission Guidelines 2019WALGEN TRADINGNo ratings yet

- Consensus Hormone ContraceptionDocument33 pagesConsensus Hormone ContraceptionSundar RamanathanNo ratings yet

- Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020 AbridgeDocument30 pagesStandards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2020 Abridgecinthya elizabeth salinas moncayoNo ratings yet

- Recommendations From The Guideline For Pcos-NoprintDocument16 pagesRecommendations From The Guideline For Pcos-NoprintpopasorinemilianNo ratings yet

- Quality Indicators For Geriatric Emergency Care: Pecial OntributionDocument9 pagesQuality Indicators For Geriatric Emergency Care: Pecial OntributionPilar Diaz VasquezNo ratings yet

- Full ReportDocument29 pagesFull ReportRima RaisyiahNo ratings yet

- Contribution of Durkheim To SociologyDocument14 pagesContribution of Durkheim To SociologyMarisa HoffmannNo ratings yet

- Week 24 DressmakingDocument3 pagesWeek 24 DressmakingBarbara PosoNo ratings yet

- Green Mountain Gazette 10 2009Document10 pagesGreen Mountain Gazette 10 2009jimestebanNo ratings yet

- Sample Student RubricDocument2 pagesSample Student RubricSaheel SinhaNo ratings yet

- Upside Down Art - MichelangeloDocument3 pagesUpside Down Art - Michelangeloapi-374986286100% (1)

- Wan Adam Ahmad: About MeDocument2 pagesWan Adam Ahmad: About MeSyafiq SyaziqNo ratings yet

- Student Centered Learning Assignment 1Document2 pagesStudent Centered Learning Assignment 1Dana AbkhNo ratings yet

- UT Dallas Syllabus For Stat1342.501.11s Taught by Yuly Koshevnik (Yxk055000)Document7 pagesUT Dallas Syllabus For Stat1342.501.11s Taught by Yuly Koshevnik (Yxk055000)UT Dallas Provost's Technology GroupNo ratings yet

- James Cameron: Early LifeDocument7 pagesJames Cameron: Early Lifeproacad writersNo ratings yet

- Future Simple TEST PDFDocument3 pagesFuture Simple TEST PDFagustinaNo ratings yet

- ENG - B1 1 0203G-Simple-Passive PDFDocument25 pagesENG - B1 1 0203G-Simple-Passive PDFankira78No ratings yet

- Essential Courses For Earning CFP, CHFC, or CluDocument1 pageEssential Courses For Earning CFP, CHFC, or CluRon CatalanNo ratings yet

- Outline of Rizal's Life 2Document73 pagesOutline of Rizal's Life 2Reyji Edduba100% (1)

- Lesson Plan-Draft 1 (Digestive System)Document4 pagesLesson Plan-Draft 1 (Digestive System)Morris Caisip ElunioNo ratings yet

- Neelima K VDocument3 pagesNeelima K Vneelima kommiNo ratings yet

- M2Me Ivb 24Document6 pagesM2Me Ivb 24ZOSIMA ONIANo ratings yet

- City Research Online: City, University of London Institutional RepositoryDocument21 pagesCity Research Online: City, University of London Institutional RepositoryRaladoNo ratings yet

- SED 1FIL-10 Panimulang Linggwistika (FIL 102)Document10 pagesSED 1FIL-10 Panimulang Linggwistika (FIL 102)BUEN, WENCESLAO, JR. JASMINNo ratings yet

- Mass Media EffectsDocument12 pagesMass Media EffectsTedi0% (1)

- Lit 179AB MeToo ShakespeareDocument5 pagesLit 179AB MeToo ShakespeareAmbereen Dadabhoy100% (1)

- ONGC GATE 2022 Cut Off MarksDocument3 pagesONGC GATE 2022 Cut Off MarksSachin BhadanaNo ratings yet

- Jessica Brooks - Resume Nurs 419 1Document1 pageJessica Brooks - Resume Nurs 419 1api-469609100No ratings yet

- Teodoro M. Kalaw Memorial School Balintawak, Lipa City Weekly Home Learning Plan Grade: 5 - ST LUKE Quarter: 1 Week: 5 (November 2-6, 2020)Document2 pagesTeodoro M. Kalaw Memorial School Balintawak, Lipa City Weekly Home Learning Plan Grade: 5 - ST LUKE Quarter: 1 Week: 5 (November 2-6, 2020)Kathrina De CastroNo ratings yet

- Dear Professor:: Tion, and Dos Mundos: en Breve, Third Edition. Both Books Will Be AvailDocument40 pagesDear Professor:: Tion, and Dos Mundos: en Breve, Third Edition. Both Books Will Be Availlinguisticahispanica0% (2)

- Application Letter: Faithfully Yours Mobile 0921245609Document6 pagesApplication Letter: Faithfully Yours Mobile 0921245609Asrade MollaNo ratings yet

- Madeleine Dugger Andrews Middle School Handbook 12-13Document34 pagesMadeleine Dugger Andrews Middle School Handbook 12-13pdallevaNo ratings yet

- Unit 1 Session 7Document3 pagesUnit 1 Session 7clayNo ratings yet