Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Education and Debate: The Search For Evidence of Effective Health Promotion

Uploaded by

S AbdOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Education and Debate: The Search For Evidence of Effective Health Promotion

Uploaded by

S AbdCopyright:

Available Formats

Education and debate

The search for evidence of effective health promotion

Viv Speller, Alyson Learmonth, D Harrison

A conceptually sound evidence base for interventions Wessex Institute for

Health Research

that aim to promote health is urgently required. How- Summary points and Development,

ever, the current search for evidence of effective health Winchester

promotion is unlikely to succeed and may result in SO22 5DH

Health promotion in the UK is at risk from the Viv Speller,

drawing false conclusions about health promotion

application of inappropriate methods of assessing senior lecturer

practice to the long term detriment of public health.

evidence, overemphasis on outcomes of North Durham

The reasons for this are threefold: lack of consensus

individual behaviour change, and pressure on Community Health

about the nature of health promotion activity; lack of Care Trust, Health

resources. Centre,

agreement over what evidence to use to assess

Chester-le-Street,

effectiveness; and divergent views on appropriate The effect of health promotion should be Durham DH3 3UR

methods for reviewing effectiveness. As a consequence assessed across the breadth of its activities and Alyson Learmonth,

health promotion may be designated “not effective” settings, not just by changes in individual health

director of health

promotion

because it is being assessed with inappropriate tools. behaviour

North West

Lancashire Health

Systematic review methods need to be revised to Promotion Unit,

What are we looking for? include a broader range of studies and research Sharoe Green

Hospital, Preston

Health promotion is a multifactorial process operating methods, including qualitative research PR2 8DU

on individuals and communities, through education, D Harrison,

prevention, and protection measures.1 The statement Review criteria should consider the quality of the health promotion

general manager

of principles known as the Ottawa charter for health health promotion intervention as well as the

promotion, developed by the World Health research design Correspondence to:

Dr Speller.

Organisation, is internationally accepted as the guiding

framework for health promotion activity. This BMJ 1997;315:361–3

describes five approaches; building healthy public

Seeking evidence of change in individual behav-

policy, creating supportive environments, strengthen-

iour or health outcome is not appropriate if

ing community action, developing personal skills, and

interventions are aiming to achieve other types of

reorienting health services.2 Health promotion meth-

change. It may be difficult to generalise from studies

ods may include activities as diverse as awareness rais-

conducted on different populations because the inter-

ing campaigns, provision of health information and

ventions and research methods may have been chosen

advice, influencing social policy, lobbying for change,

to answer different questions about different types of

professional training, and community development—

health promotion practice. The logic of looking for

often in combination in complex interventions.

immediate changes in health or behaviour as a result of

However, health promotion is rarely judged on its

one shot interventions, such as advice from health pro-

effectiveness in all these areas.

fessionals or advertising, is questionable when we know

that attitudes and behaviours are shaped by a panoply

Not just about individual behaviour of socioeconomic and cultural influences. Attribution

In Britain the Health of the Nation strategy’s of any changes detected to a single intervention is also

concentration on reducing disease and behavioural dubious. Despite calls to refocus population health

risk factors3 has overemphasised the role of health “upstream,” many research studies are still seeking such

promotion in developing personal knowledge and simple results with little consideration of the effect of

skills and focused attention on assessing individual other influences, or use costly designs to attempt to

health outcomes. In Europe, however, health promo- control them.6

tion emphasises the development of health promoting

settings, such as schools, workplaces and hospitals,

How should we look for evidence of

which aim to enable and support healthy behaviour.

Practice therefore includes management and organisa-

effectiveness?

tional development approaches.4 In the Pacific Britain’s national research and development pro-

countries the emphasis is on sustaining healthy gramme is not supporting health promotion research

environments, and legislative approaches are aimed at because it is dominated by clinically oriented criteria

populations, rather than individuals.5 and methods. Evidence based medicine is defined as

BMJ VOLUME 315 9 AUGUST 1997 361

Education and debate

intercourse. An experienced health promoter would

immediately know that this is unlikely to have been an

appropriate intervention method for this target group.

Process evaluation may be useful

As randomised trials are expensive, it is important that

they are applied only to study high quality interven-

tions that have been developed appropriately and

based on knowledge of best practice. Another

CHRISTOPHE BLUNTZER/IMPACT

approach to assessing effectiveness which pays more

attention to the quality of the intervention has been

attempted by the International Union for Health Pro-

motion and Education in a series of 16 effectiveness

reviews.15 Criteria for selecting studies included

information about the strategies used in the interven-

There is more to health promotion than reducing behavioural risk factors tion. Evaluation criteria included not only the use of

controls and measurements before and after the inter-

vention but also formative or process evaluation. This

“the conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of is the study of the processes of implementing the inter-

current best evidence in making decisions about the vention, to answer such questions as: was it applied in

care of individual patients.”7 The systematic review the manner intended, did other factors come into play

process aims to ensure reliable and rigorous evaluation that might have affected the result, what did the partici-

of evidence. Criteria for the inclusion of studies usually pants think about the process? Process evaluation

place randomised controlled trials as the gold standard often uses qualitative research methods and comple-

for judging whether a treatment is effective. This ments outcome evaluation. In health promotion

approach has been directly transferred to health research the technique of “triangulation”—that is,

promotion in the series of reviews by the NHS Centre drawing conclusions from a number of different

for Reviews and Dissemination to determine what is sources of data—is also used.

known about the effectiveness of health promotion There are several important differences between

interventions. This evidence is now becoming available the approach to review taken by the International

through the Effective Health Care Bulletin series8 9 and Union for Health Promotion and Education and the

the Health Education Authority series of health systematic review approach of the Centre for Reviews

promotion effectiveness reviews.10 11 and Dissemination. While the latter pays inadequate

The selection of studies for inclusion is done on the attention to the process of the intervention, the former

basis of the quality of the research only, not on the is insufficiently critical of the soundness of quantitative

quality of the health promotion intervention. This can research methods. It would be helpful to attempt to

produce some anomalous results. An earlier bulletin combine the best elements of both for future effective-

on brief interventions and alcohol use12 suggested that ness reviews.

brief interventions are as effective as more expensive Another fundamental problem with using ran-

specialist treatment. This sparked a debate about the domised controlled trials in health promotion research

meaning of the term “brief interventions” which high- is that where interventions aim to influence systems or

lighted the risks inherent in glossing over the detail.13 populations it may be difficult to randomly allocate

The intervention techniques had been pooled because units such as schools or communities to intervention

they were all said to be of similar short duration and or control groups, so quasiexperimental control

had common characteristics. However, these ranged designs are used. Well known quasiexperimental stud-

from five minutes of simple advice to regular sessions ies include the Stanford heart disease prevention pro-

over six months of structured interventions by a gram16 and the Minnesota heart health program,17

general practitioner. It is clearly difficult from this for where multiple interventions were applied to commu-

the commissioner or practitioner to determine which nities and their risk factor profiles were subsequently

intervention technique is most successful. compared with matched comparison communities.

Another systematic review looked at the effective- One of the major problems with studies employing this

ness of sexual health education interventions for design is the “contamination” of the control group.

young people.14 Of 270 papers reporting sexual health This poses a serious dilemma in that the practice of

interventions only 12 met the inclusion criteria. Crite- health promotion relies strongly on the diffusion of the

ria such as the appropriateness of the interventions effects of the intervention through the target

studied and outcome measures used were not community. The difficulty of controlling for spillover to

considered essential “because of the large element of the comparison community reduces the effect attribut-

subjectivity in assessing whether they had been met.” able to the intervention. Whether health gain in the

This can lead to spurious generalised conclusions, such control group is influenced by diffusion of the

as that drawn from a US study of an abstinence educa- intervention, or the intervention group effects are pro-

tion programme for 13 year old boys from a low duced by secular trends, cannot be determined by

income minority group, that chastity education is looking at outcome measures alone.

harmful. The study was included despite high attrition As has been recognised for healthcare evaluation,

rates and dependence on self reported outcomes. After a wide range of research methods is warranted.18

six lessons aimed at reducing premarital sex, more of Qualitative research can contribute to assessing the

the intervention group claimed to have initiated sexual effectiveness of interventions by illuminating proc-

362 BMJ VOLUME 315 9 AUGUST 1997

Education and debate

esses, exploring diversity, and developing new theories. cross cutting themes to examine the effectiveness of

It includes a broad range of methods such as case different methods of health promotion.

study, ethnography, action research, participant obser- Research should be commissioned to fill the gaps

vation, conversation analysis, and grounded theory.19 identified by the reviews, ensuring that an appropriate

For example, a textual analysis of the way health range of methods is used. In doing this practitioners

visitors provide information to first time mothers iden- need to be involved in designing and implementing

tified that they frequently failed to reinforce the viable interventions including collecting data for proc-

mother as a skilful and knowledgeable person, thereby ess evaluation to ensure that programmes function

affecting the reception of advice.20 Ethnographic stud- optimally. It is essential for health promotion research

ies provide a way of assessing outcomes of health pro- to bring together experts from a range of disciplines to

motion interventions on activities such as injecting design and conduct studies that pay adequate attention

drug use and cannabis dealing which may not be ame- to both the quality of the intervention and the methods

nable to other research methods.21 22 of evaluation.

Finally, the evidence base must be accessible to and

used by practitioners. While practitioners need to be

Will we recognise effective health more critical and to substantiate their decisions with

promotion when we find it? evidence, key messages must also be disseminated

An inquiry by Britain’s parliamentary public accounts clearly and unequivocally to influence practice.

committee into the cost effectiveness of the Health of the If the commitment enshrined in the mission for the

Nation strategy showed that spending on health promo- NHS—to promote health and prevent disease as well as

tion in 1996 was £3m on the strategy, £45m on health providing treatment—is to be taken seriously, then the

education via the Health Education Authority, £73m on national research and development agenda needs to

paying general practitioners for health promotion work, consider ways of tackling these issues. Action needs to

and £90m on NHS health promotion units.23 This be taken urgently to redress the negative consequences

represents less than 1% of the NHS’s annual budget and on health promotion of a misdirected search which is

less than the expenditure on staff cars and travelling and veering off course.

subsistence in 1994-5.24 Yet anecdotal evidence suggests

that cost pressures, coupled with the inability to present 1 Tannahill A. What is health promotion? Health Education Journal

conclusive evidence of effectiveness, are conspiring to 1985;44:167-8.

2 World Health Organisation. The Ottawa charter: principles for health promo-

make health promotion contracts a soft option for tion. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 1986.

budget cuts in next year’s contracts. 3 Department of Health. Health of the nation. London: HMSO, 1992.

4 Grossman R, Scala K. Health promotion and organisational development:

To get out of this downward spiral health developing settings for health. Vienna: WHO, 1993.

promotion workers must demonstrate evidence of its 5 Central Sydney Area Health Service and NSW Health. Program manage-

ment guidelines for health promotion. Sydney: Better Health Centre, 1994.

effectiveness by establishing a robust evidence base. 6 Population health looking upstream. Lancet 1994;343:429-30.

Existing reviews should be critically reanalysed using 7 Sackett DL, Rosenberg WC, Muir Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS.

Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 1996;312:71-2.

appropriate inclusion criteria which consider the qual- 8 NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Preventing falls and

ity of the health promotion intervention as well as that unintentional injuries in older people. Effective Health Care 1996;2:4.

9 NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Unintentional injuries in

of the research. Criteria for rigorous evaluation of young people. Effective Health Care 1996;2:5.

qualitative research methods need to be derived. The 10 Ebrahim S, Davey-Smith G. Health promotion in older people for the

prevention of coronary heart disease and stroke. London: Health Educa-

search should be broadened to include studies that tion Authority, 1996.

measure the impact of interventions on systems and 11 Towner E, Dowswell T, Simpson G, Jarvis S. Health promotion in

childhood and young adolescence for the prevention of unintentional

organisational development as well as change in injuries. London: Health Education Authority, 1996.

individual behaviour. Further work needs to be done 12 NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Brief interventions and

using the existing health topic based reviews to analyse alcohol use. Effective Health Care 1993;7.

13 Heather N. Interpreting the evidence on brief interventions for excessive

drinkers: the need for caution. Alcohol and Alcoholism 1995;30:287-96.

14 Oakley A, Fullerton D, Holland J, Arnold S, France-Dawson M, Kelley P,

et al. Sexual health interventions for young people: a methodological

review. BMJ 1995;310,158-62.

15 Veen CA, Vereijken I, van Driel WG, Belien M A. An instrument for analys-

ing effectiveness studies on health promotion and health education. Utrecht:

Dutch Centre for Health Promotion and Health Education and IUHPE/

EURO 1994.

16 Farquhar J, Fortmann S, Flora J, Taylor CB, Haskell WL, Williams PT, et al.

Effects of community-wide education on cardiovascular disease risk

factors. The Stanford five city project. JAMA 1990;264:359-65.

17 Luepker R, Murray D, Jacobs D, Mittelmark MB, Bracht N, Carlaw R, et al.

Community education for cardiovascular disease prevention: risk factor

changes in the Minnesota heart health program. Am J Pub Health

1994;84:1383-93.

18 Black N. Why we need observational studies to evaluate the effectiveness

of health care. BMJ 1996;312:1215-8.

19 Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. Handbook of qualitative research. London: Sage,

1994.

20 Heritage J, Sefi S. Dilemmas of advice giving: aspects of the delivery and

reception of advice in interactions between health visitors and first time

mothers. In: Drew P, Heritage J, eds. Talk at work. Cambridge: Cambridge

University Press, 1992:59-417.

21 Taylor A. Women drug users: an ethnography of a female injecting community.

Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1993.

22 Fountain J. Dealing with data. In: Hobbs D, May T, eds. Interpreting the field.

Beverley Hills, CA: Sage, 1993:145-73.

23 Limb L. Health of the Nation under scrutiny. Health Services Journal

ZEFA

1996;14 Nov:8.

But will this make her healthier? 24 Monitor. Health Services Journal 1996;14 Nov:25.

(Accepted 3 February 1997)

BMJ VOLUME 315 9 AUGUST 1997 363

Education and debate

How to read a paper

Statistics for the non-statistician. I: Different types of data

need different statistical tests

This is the As medicine leans increasingly on mathematics no

fourth in a clinician can afford to leave the statistical aspects of Summary points

series of 10 a paper to the “experts.” If you are numerate, try the

articles “Basic Statistics for Clinicians” series in the Canadian

In assessing the choice of statistical tests in a

introducing Medical Association Journal,1-4 or a more mainstream

paper, first consider whether groups were

non-experts to statistical textbook.5 If, on the other hand, you find sta-

analysed for their comparability at baseline

finding medical tistics impossibly difficult, this article and the next in

articles and this series give a checklist of preliminary questions to Does the test chosen reflect the type of data

assessing their help you appraise the statistical validity of a paper. analysed (parametric or non-parametric, paired

value or unpaired)?

Have the authors set the scene correctly?

Unit for Has a two tailed test been performed whenever

Evidence-Based Have they determined whether their groups are comparable, the effect of an intervention could conceivably be

Practice and Policy, and, if necessary, adjusted for baseline differences?

Department of a negative one?

Primary Care and Most comparative clinical trials include either a table

Population or a paragraph in the text showing the baseline charac- Have the data been analysed according to the

Sciences, University

College London

teristics of the groups being studied. Such a table original study protocol?

Medical School/ should show that the intervention and control groups

Royal Free Hospital are similar in terms of age and sex distribution and key If obscure tests have been used, do the authors

School of Medicine,

Whittington prognostic variables (such as the average size of a can- justify their choice and provide a reference?

Hospital, London cerous lump). Important differences in these character-

N19 5NF istics, even if due to chance, can pose a challenge to

Trisha Greenhalgh,

your interpretation of results. In this situation, numbers for a particular sample of cases, but we would

senior lecturer

adjustments can be made to allow for these differences be completely unable to interpret the result. The same

p.greenhalgh@ucl.

ac.uk and hence strengthen the argument.6 would apply if we labelled the property “liking for x”

with 1 = not at all, 2 = a bit, and 3 = a lot. Again, we

BMJ 1997;315:364–6 What sort of data have they got, and have they used could calculate the “average liking,” but the numerical

appropriate statistical tests? result would be uninterpretable unless we knew that the

Numbers are often used to label the properties of difference between “not at all” and “a bit” was exactly

things. We can assign a number to represent our height, the same as the difference between “a bit” and “a lot.”

weight, and so on. For properties like these, the All statistical tests are either parametric (that is, they

measurements can be treated as actual numbers. We assume that the data were sampled from a particular

can, for example, calculate the average weight and form of distribution, such as a normal distribution) or

height of a group of people by averaging the measure- non-parametric (they make no such assumption). In

ments. But consider an example in which we use num- general, parametric tests are more powerful than non-

bers to label the property “city of origin,” where parametric ones and so should be used if possible.

1 = London, 2 = Manchester, 3 = Birmingham, and so Non-parametric tests look at the rank order of the

on. We could still calculate the average of these values (which one is the smallest, which one comes

next, and so on) and ignore the absolute differences

between them. As you might imagine, statistical

significance is more difficult to show with non-

parametric tests, and this tempts researchers to use

statistics such as the r value inappropriately. Not only is

the r value (parametric) easier to calculate than its

non-parametric equivalent but it is also much more

likely to give (apparently) significant results.

Unfortunately, it will give a spurious estimate of the

significance of the result, unless the data are appropri-

ate to the test being used. More examples of paramet-

ric tests and their non-parametric equivalents are given

in table 1.

Another consideration is the shape of the distribu-

tion from which the data were sampled. When I was at

school, my class plotted the amount of pocket money

received against the number of children receiving that

PETER BROWN

amount. The results formed a histogram the same

shape as figure 1—a “normal” distribution. (The term

“normal” refers to the shape of the graph and is used

364 BMJ VOLUME 315 9 AUGUST 1997

Education and debate

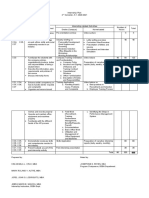

Table 1 Some commonly used statistical tests

Example of equivalent

Parametric test non-parametric test Purpose of test Example

Two sample (unpaired) t test Mann-Whitney U test Compares two independent samples drawn from To compare girls’ heights with boys’

the same population heights

One sample (paired) t test Wilcoxon matched pairs test Compares two sets of observations on a single To compare weight of infants before and

sample after a feed

One way analysis of variance Kruskall-Wallis analysis of Effectively, a generalisation of the paired t or To determine whether plasma glucose

(F test) using total sum of variance by ranks Wilcoxon matched pairs test where three or more level is higher one hour, two hours, or

squares sets of observations are made on a single sample three hours after a meal

Two way analysis of variance Two way analysis of variance As above, but tests the influence (and In the above example, to determine if the

by ranks interaction) of two different covariates results differ in male and female subjects

÷2 test Fisher’s exact test Tests the null hypothesis that the distribution of To assess whether acceptance into

a discontinuous variable is the same in two (or medical school is more likely if the

more) independent samples applicant was born in Britain

Product moment correlation Spearman’s rank correlation Assesses the strength of the straight line To assess whether and to what extent

coefficient (Pearson’s r) coefficient (ró) association between two continuous variables. plasma HbA1 concentration is related to

plasma triglyceride concentration in

diabetic patients

Regression by least squares Non-parametric regression Describes the numerical relation between two To see how peak expiratory flow rate

method (various tests) quantitative variables, allowing one value to be varies with height

predicted from the other

Multiple regression by least Non-parametric regression Describes the numerical relation between a To determine whether and to what extent a

squares method (various tests) dependent variable and several predictor person’s age, body fat, and sodium intake

variables (covariates) determine their blood pressure

because many biological phenomena show this pattern Are the data analysed according to the original protocol?

of distribution). Some biological variables such as body If you play coin toss with someone, no matter how far

weight show “skew normal” distribution, as shown in you fall behind, there will come a time when you are

figure 2. (Figure 2 shows a negative skew, whereas body one ahead. Most people would agree that to stop the

weight would be positively skewed. The average adult game then would not be a fair way to play. So it is with

male body weight is 70 kg, and people exist who weigh research. If you make it inevitable that you will (eventu-

140 kg, but nobody weighs less than nothing, so the ally) get an apparently positive result you will also

graph cannot possibly be symmetrical.) make it inevitable that you will be misleading yourself

Non-normal (skewed) data can sometimes be about the justice of your case.7 (Terminating an

transformed to give a graph of normal shape by intervention trial prematurely for ethical reasons when

performing some mathematical transformation (such subjects in one arm are faring particularly badly is a

as using the variable’s logarithm, square root, or recip- different matter and is discussed elsewhere.7)

rocal). Some data, however, cannot be transformed into Raking over your data for “interesting results” (ret-

a smooth pattern. For a very readable discussion of the rospective subgroup analysis) can lead to false conclu-

normal distribution see chapter 7 of Martin Bland’s

Introduction to Medical Statistics.5

Deciding whether data are normally distributed is

Frequency

not an academic exercise, since it will determine what

type of statistical tests to use. For example, linear

regression will give misleading results unless the points

on the scatter graph form a particular distribution

about the regression line—that is, the residuals (the

perpendicular distance from each point to the line)

should themselves be normally distributed. Transform-

ing data to achieve a normal distribution (if this is

indeed achievable) is not cheating: it simply ensures

that data values are given appropriate emphasis in

Number

assessing the overall effect. Using tests based on the

Fig 1 Normal curve

normal distribution to analyse non-normally distrib-

uted data, however, is definitely cheating.

If the authors have used obscure statistical tests, why have

Frequency

they done so and have they referenced them?

The number of possible statistical tests sometimes

seems infinite. In fact, most statisticians could survive

with a formulary of about a dozen. The rest should

generally be reserved for special indications. If the

paper you are reading seems to describe a standard set

of data which have been collected in a standard way,

but the test used has an unpronounceable name and is

not listed in a basic statistics textbook, you should smell

a rat. The authors should, in such circumstances, state Number

why they have used this test, and give a reference (with Fig 2 Skewed curve

page numbers) for a definitive description of it.

BMJ VOLUME 315 9 AUGUST 1997 365

Education and debate

sions.8 In an early study on the use of aspirin in increase it. Hence, your statistical analysis should, in

preventing stroke, the results showed a significant general, test the hypothesis that either high or low val-

effect in both sexes combined, and a retrospective sub- ues in your dataset have arisen by chance. In the

group analysis seemed to show that the effect was con- language of the statisticians, this means you need a two

fined to men.9 This conclusion led to aspirin being tailed test, unless you have very convincing evidence

withheld from women for many years, until the results that the difference can only be in one direction.

of other studies10 showed that this subgroup effect was

spurious.

This and other examples are included in Oxman Were “outliers” analysed with both common sense and

and Guyatt’s, “A consumer’s guide to subgroup appropriate statistical adjustments?

analysis,” which reproduces a useful checklist for decid- Unexpected results may reflect idiosyncrasies in the

ing whether apparent subgroup differences are real.11 subject (for example, unusual metabolism), errors in

measurement (faulty equipment), errors in inter-

pretation (misreading a meter reading), or errors in

Paired data, tails, and outliers calculation (misplaced decimal points). Only the first of

Were paired tests performed on paired data? these is a “real” result which deserves to be included in

Students often find it difficult to decide whether to use the analysis. A result which is many orders of

a paired or unpaired statistical test to analyse their magnitude away from the others is less likely to be

data. There is no great mystery about this. If you meas- genuine, but it may be so. A few years ago, while doing

ure something twice on each subject—for example, a research project, I measured several different

blood pressure measured when the subject is lying and hormones in about 30 subjects. One subject’s growth

when standing—you will probably be interested not hormone levels came back about 100 times higher

just in the average difference of lying versus standing than everyone else’s. I assumed this was a transcription

blood pressure in the entire sample, but in how much error, so I moved the decimal point two places to the

each individual’s blood pressure changes with position. left. Some weeks later, I met the technician who had

In this situation, you have what is called “paired” data, analysed the specimens and he asked, “Whatever hap-

because each measurement beforehand is paired with pened to that chap with acromegaly?”

a measurement afterwards. Statistically correcting for outliers (for example, to

In this example, it is using the same person on both modify their effect on the overall result) requires

occasions which makes the pairings, but there are sophisticated analysis and is covered elsewhere.6

other possibilities (for example, any two measurements

of bed occupancy made of the same hospital ward). In

these situations, it is likely that the two sets of values will

be significantly correlated (for example, my blood The articles in this series are excerpts from How to

pressure next week is likely to be closer to my own read a paper: the basics of evidence based medicine. The

blood pressure last week than to the blood pressure of book includes chapters on searching the literature

a randomly selected adult last week). In other words, we and implementing evidence based findings. It can

be ordered from the BMJ Bookshop: tel 0171 383

would expect two randomly selected paired values to

6185/6245; fax 0171 383 6662. Price £13.95 UK

be closer to each other than two randomly selected members, £14.95 non-members.

unpaired values. Unless we allow for this, by carrying

out the appropriate paired sample tests, we can end up

with a biased estimate of the significance of our results.

I am grateful to Mr John Dobby for educating me on statistics

Was a two tailed test performed whenever the effect of an and for repeatedly checking and amending this article. Respon-

intervention could conceivably be a negative one? sibility for any errors is mine alone.

The term “tail” refers to the extremes of the distri-

bution—the areas at the outer edges of the bell in figure

1 Guyatt G, Jaenschke R, Heddle, N, Cook D, Shannon H, Walter S. Basic

1. Let’s say that the graph represents the diastolic blood statistics for clinicians. 1. Hypothesis testing. Can Med Assoc J

pressures of a group of people of which a random 1995;152:27-32.

2 Guyatt G, Jaenschke R, Heddle, N, Cook D, Shannon H, Walter S. Basic

sample are about to be put on a low sodium diet. If a statistics for clinicians. 2. Interpreting study results: confidence intervals.

low sodium diet has a significant lowering effect on Can Med Assoc J 1995;152:169-73.

blood pressure, subsequent blood pressure measure- 3 Jaenschke R, Guyatt G, Shannon H, Walter S, Cook D, Heddle, N. Basic

statistics for clinicians: 3. Assessing the effects of treatment: measures of

ments on these subjects would be more likely to lie association. Can Med Assoc J 1995;152:351-7.

within the left tail of the graph. Hence we would 4 Guyatt G, Walter S, Shannon H, Cook D, Jaenschke R, Heddle, N. Basic

statistics for clinicians. 4. Correlation and regression. Can Med Assoc J

analyse the data with statistical tests designed to show 1995;152:497-504.

whether unusually low readings in this patient sample 5 Bland M. An introduction to medical statistics. Oxford: Oxford University

were likely to have arisen by chance. Press, 1987.

6 Altman D. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman and

But on what grounds may we assume that a low Hall, 1995.

sodium diet could only conceivably put blood pressure 7 Hughes MD, Pocock SJ. Stopping rules and estimation problems in clini-

cal trials. Statistics in Medicine 1987;7:1231-42.

down, but could never do the reverse, put it up? Even if 8 Stewart LA, Parmar MKB. Bias in the analysis and reporting of

there are valid physiological reasons in this particular randomized controlled trials. Int J Health Technology Assessment

example, it is certainly not good science always to 1996;12:264-75.

9 Canadian Cooperative Stroke Group. A randomised trial of aspirin and

assume that you know the direction of the effect which sulfinpyrazone in threatened stroke. N Engl J Med 1978;299:53-9.

your intervention will have. A new drug intended to 10 Antiplatelet Trialists Collaboration. Secondary prevention of vascular

disease by prolonged antiplatelet treatment. BMJ 1988;296:320-1.

relieve nausea might actually exacerbate it, or an 11 Oxman, AD, Guyatt GH. A consumer’s guide to subgroup analysis. Ann

educational leaflet intended to reduce anxiety might Intern Med 1992;116:79-84.

366 BMJ VOLUME 315 9 AUGUST 1997

You might also like

- Health Education - Lecture Notes PDFDocument60 pagesHealth Education - Lecture Notes PDFPetros Ndumba100% (8)

- Module - I: 2.Milio'S Framework For PreventionDocument26 pagesModule - I: 2.Milio'S Framework For PreventionIanaCarandang100% (3)

- Policy and Procedures For Hiring, PromotionsDocument2 pagesPolicy and Procedures For Hiring, PromotionsRazel Ann ElagioNo ratings yet

- Escape From The Western Diet Summary RevisedDocument3 pagesEscape From The Western Diet Summary Revisedapi-385530863100% (1)

- 2014 - Does Health Coaching WorkDocument25 pages2014 - Does Health Coaching WorkGONDHES CHANNELNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion: An Integral Discipline of Public HealthDocument6 pagesHealth Promotion: An Integral Discipline of Public HealthUsman Ahmad TijjaniNo ratings yet

- Practicing Health Promotion in Primary CareDocument6 pagesPracticing Health Promotion in Primary CareAlfia NadiraNo ratings yet

- Part 1 Jennie Naidoo - Jane Wills, MSC - Developing Practice For Public Health and Health Promotion-Bailliere Tindall - Elsevier (2010) (1) (018-092)Document75 pagesPart 1 Jennie Naidoo - Jane Wills, MSC - Developing Practice For Public Health and Health Promotion-Bailliere Tindall - Elsevier (2010) (1) (018-092)flameglitter21No ratings yet

- Health Promotion Strategies For NursesDocument2 pagesHealth Promotion Strategies For Nursespuding101No ratings yet

- DownloadDocument12 pagesDownloadMUHAMMAD FARIS SASMANNo ratings yet

- Research ArticleDocument32 pagesResearch ArticleEliezer NuenayNo ratings yet

- Ethics and Evidence - An Alternative View of HPDocument9 pagesEthics and Evidence - An Alternative View of HPTerence FusireNo ratings yet

- HIA Guide For PracticeDocument89 pagesHIA Guide For PracticeMariamNo ratings yet

- AJGP 10 2019 Focus Conn Health Coaching Lifestyle Medicine WEB 1Document4 pagesAJGP 10 2019 Focus Conn Health Coaching Lifestyle Medicine WEB 1Lely jumriani baktiNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion PGDocument16 pagesHealth Promotion PGp.gargNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion and Health Education: Bardarash Technical Institute Nursing DepartmentDocument36 pagesHealth Promotion and Health Education: Bardarash Technical Institute Nursing Departmentarazw IssaNo ratings yet

- Sách theo dõi đánh giá chương trình y tếDocument19 pagesSách theo dõi đánh giá chương trình y tếTran Quyet TienNo ratings yet

- 2nd CLASS ENG - HEALTH PROMOTIONDocument3 pages2nd CLASS ENG - HEALTH PROMOTIONS VaibhavNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion Models - PHOP 4 2017 - 2018 - YFDocument58 pagesHealth Promotion Models - PHOP 4 2017 - 2018 - YFFaishalNo ratings yet

- AH RI Quality Improvement UASDocument5 pagesAH RI Quality Improvement UASSrikit NurkamidenNo ratings yet

- Atestados de La Rueda de Cambio de ComportamientoDocument7 pagesAtestados de La Rueda de Cambio de Comportamientovero060112.vcNo ratings yet

- CCM: Community: Sumberdaya Dan Kebijakan KomunitasDocument53 pagesCCM: Community: Sumberdaya Dan Kebijakan KomunitasAlvinNo ratings yet

- Health PromotionDocument16 pagesHealth PromotionSushma LathNo ratings yet

- Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change - Background and Intervention DevelopmentDocument10 pagesIntegrated Theory of Health Behavior Change - Background and Intervention Developmentvero060112.vcNo ratings yet

- Phpe 210Document2 pagesPhpe 210Reg LagartejaNo ratings yet

- 1 - Method-and-Approaches of HPDocument63 pages1 - Method-and-Approaches of HPPutri EsaNo ratings yet

- Unit 3-Health Promotion and DiversityDocument37 pagesUnit 3-Health Promotion and DiversityKrista KloseNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plane On Health Promotion.Document6 pagesLesson Plane On Health Promotion.Topeshwar TpkNo ratings yet

- Nursing Process in The Care of The POPULATION GROUPSDocument3 pagesNursing Process in The Care of The POPULATION GROUPSCailah Sofia SelausoNo ratings yet

- Approaches To Health PromotionDocument4 pagesApproaches To Health PromotionJade Xy MasculinoNo ratings yet

- Health PromotionDocument30 pagesHealth PromotionZareen Tasnim Tapti 2225036080No ratings yet

- International Journal of Nursing Studies: ArticleinfoDocument16 pagesInternational Journal of Nursing Studies: Articleinfodewi retnoNo ratings yet

- Aminu Magaji T-PDocument27 pagesAminu Magaji T-PUsman Ahmad TijjaniNo ratings yet

- Materi - Method and Approaches in HPDocument98 pagesMateri - Method and Approaches in HPdiniindahlestariNo ratings yet

- Healthpromotion 190406154250Document77 pagesHealthpromotion 190406154250Latuloho Malay Colo MochoNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument21 pagesUntitledSan MohapatraNo ratings yet

- Band UraDocument23 pagesBand UraAnonymous FTdGFgNo ratings yet

- A1 Introduction To Health PromotionDocument17 pagesA1 Introduction To Health PromotionAfia SarpongNo ratings yet

- Community Health EducationDocument5 pagesCommunity Health EducationCharlene LunaNo ratings yet

- Improving Health and Reducing Inequalities A Practical Guide To HIA - WAG Wales - 2004Document36 pagesImproving Health and Reducing Inequalities A Practical Guide To HIA - WAG Wales - 2004PublicHealthbyDesignNo ratings yet

- Tacking The Wider Determinants of Health InequalityDocument8 pagesTacking The Wider Determinants of Health InequalitymammaofxyzNo ratings yet

- Health Services System ManagementDocument21 pagesHealth Services System ManagementShimmering MoonNo ratings yet

- Activity 4-PHDocument5 pagesActivity 4-PHKate MendozaNo ratings yet

- Beacon Schools Project Health Education Level 8 Planning Guide Section 6Document8 pagesBeacon Schools Project Health Education Level 8 Planning Guide Section 6api-3803295No ratings yet

- Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare: EditorialDocument2 pagesSexual & Reproductive Healthcare: Editorialardian jayakusumaNo ratings yet

- Social Cognitive Theory - Bandura - Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means - 2004 PDFDocument22 pagesSocial Cognitive Theory - Bandura - Health Promotion by Social Cognitive Means - 2004 PDFZuzu FinusNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion ModelDocument5 pagesHealth Promotion ModelMakau ElijahNo ratings yet

- Health Promot. Int.-2008-Tannahill-380-90Document11 pagesHealth Promot. Int.-2008-Tannahill-380-90Terence FusireNo ratings yet

- Paparan Semnas Promkes-Sapja AnantanyuDocument25 pagesPaparan Semnas Promkes-Sapja AnantanyuyuliaNo ratings yet

- Pabo - GOOD HEALTH AND WELL-BEINGDocument4 pagesPabo - GOOD HEALTH AND WELL-BEINGPA-PABO, Christine Jane A.No ratings yet

- Advantages and Disadvantages of Health Care AccredDocument32 pagesAdvantages and Disadvantages of Health Care Accredgiuliano moralesNo ratings yet

- Je CH 082743Document8 pagesJe CH 082743Anggriyani Wahyu PinandariNo ratings yet

- What Strategies Help To Promote The Health of Individuals?Document1 pageWhat Strategies Help To Promote The Health of Individuals?FlaaffyNo ratings yet

- What Are Health Information Systems, and Why Are They Important?Document7 pagesWhat Are Health Information Systems, and Why Are They Important?Malick GaiNo ratings yet

- Col Zulfiquer Ahmed Amin: M Phil (HHM), MPH (HM), PGD (Health Economics), MBBS Armed Forces Medical Institute (AFMI)Document60 pagesCol Zulfiquer Ahmed Amin: M Phil (HHM), MPH (HM), PGD (Health Economics), MBBS Armed Forces Medical Institute (AFMI)Manav Suman SinghNo ratings yet

- Health Promotion and Health Education 11.24.22Document99 pagesHealth Promotion and Health Education 11.24.22Compilation 2021No ratings yet

- C1 NCM 102Document20 pagesC1 NCM 102Khecia Freanne TorresNo ratings yet

- Health Literacy: Applying Current Concepts To Improve Health Services and Reduce Health InequalitiesDocument10 pagesHealth Literacy: Applying Current Concepts To Improve Health Services and Reduce Health InequalitiesasriadiNo ratings yet

- Knowledge Translation and Behaviour Change: Patients, Providers, and PopulationsDocument2 pagesKnowledge Translation and Behaviour Change: Patients, Providers, and PopulationsyodaNo ratings yet

- NR527 Module 3 (Health Promotion)Document5 pagesNR527 Module 3 (Health Promotion)96rubadiri96No ratings yet

- What Is Peer Education and How Peer Education Is Used - AdetDocument4 pagesWhat Is Peer Education and How Peer Education Is Used - AdetFamelasari Fitria RamdaniNo ratings yet

- برنامج الهندسة الكهربائيةDocument2 pagesبرنامج الهندسة الكهربائيةS AbdNo ratings yet

- Skit PDFDocument6 pagesSkit PDFPeterJLYNo ratings yet

- How To Publish A Scientific Manuscript in A High-Impact JournalDocument5 pagesHow To Publish A Scientific Manuscript in A High-Impact JournalS AbdNo ratings yet

- Comparision of PSO and GADocument13 pagesComparision of PSO and GAEswaranNo ratings yet

- A Survey of Fractional Order Calculus Applications of Multiple-Input, Multiple-Output (MIMO) Process ControlDocument32 pagesA Survey of Fractional Order Calculus Applications of Multiple-Input, Multiple-Output (MIMO) Process ControlS AbdNo ratings yet

- Soil Biology and BiochemistryDocument3 pagesSoil Biology and BiochemistryS AbdNo ratings yet

- Chaos, Solitons and Fractals: Vinay Kumar Reddy Chimmula, Lei ZhangDocument6 pagesChaos, Solitons and Fractals: Vinay Kumar Reddy Chimmula, Lei ZhangS AbdNo ratings yet

- Soil Biology and BiochemistryDocument3 pagesSoil Biology and BiochemistryS AbdNo ratings yet

- Soil Biology and BiochemistryDocument3 pagesSoil Biology and BiochemistryS AbdNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Ijleo 2020 165155 PDFDocument19 pages10 1016@j Ijleo 2020 165155 PDFS AbdNo ratings yet

- Research On Position Servo System Based On FractioDocument10 pagesResearch On Position Servo System Based On FractioS AbdNo ratings yet

- Filtering and ConvolutionsDocument15 pagesFiltering and ConvolutionssoumikbhNo ratings yet

- Hamiltonian-Based Energy Analysis For Brushless DC Motor Chaotic SystemDocument14 pagesHamiltonian-Based Energy Analysis For Brushless DC Motor Chaotic SystemS AbdNo ratings yet

- Supersymmetric Artificial Neural Network 2Document5 pagesSupersymmetric Artificial Neural Network 2S AbdNo ratings yet

- 12 29 11editionDocument27 pages12 29 11editionSan Mateo Daily JournalNo ratings yet

- May 2 Homework Solutions: S M X CDocument3 pagesMay 2 Homework Solutions: S M X CClerry SamuelNo ratings yet

- Problem 21-02 Wright Company Spreadsheet For The Statement of Cash Flows Dec. 31 Changes Dec. 31 2020 Debits Credits 2021 Balance SheetDocument17 pagesProblem 21-02 Wright Company Spreadsheet For The Statement of Cash Flows Dec. 31 Changes Dec. 31 2020 Debits Credits 2021 Balance SheetVishal P RaoNo ratings yet

- Research 101Document14 pagesResearch 101Ace Ryu SmithNo ratings yet

- Lifan 152F Engine Parts (80Cc) : E 01 Crankcase AssemblyDocument13 pagesLifan 152F Engine Parts (80Cc) : E 01 Crankcase AssemblySean MurrayNo ratings yet

- Arduino CertificationDocument8 pagesArduino Certificationhack reportNo ratings yet

- PSV Sizing For Two Phase FlowDocument28 pagesPSV Sizing For Two Phase FlowSyed Haideri100% (1)

- PBL 3 - Toothache Drugs and MedicationsDocument10 pagesPBL 3 - Toothache Drugs and MedicationsAlbert LawNo ratings yet

- Week 1Document14 pagesWeek 1kohalehNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 - Assessment of PostureDocument31 pagesChapter 3 - Assessment of Posturehis.thunder122No ratings yet

- Korean Wellhead KWM-2014-Revision0Document20 pagesKorean Wellhead KWM-2014-Revision0DrakkarNo ratings yet

- Arrival Guide To MalaysiaDocument2 pagesArrival Guide To Malaysiaamanu092No ratings yet

- Internship-Plan BSBA FInalDocument2 pagesInternship-Plan BSBA FInalMark Altre100% (1)

- Banana Disease 2 PDFDocument4 pagesBanana Disease 2 PDFAlimohammad YavariNo ratings yet

- Production & Downstream Processing of Baker's Best FriendDocument26 pagesProduction & Downstream Processing of Baker's Best FriendMelissaNo ratings yet

- Lab Manual For Series Parallel Rasonant CircuitDocument3 pagesLab Manual For Series Parallel Rasonant CircuitManoj PardhanNo ratings yet

- Brown Wolf ExerciseDocument8 pagesBrown Wolf ExerciseAarnav kumar0% (1)

- Distance Learning in Clinical MedicalDocument7 pagesDistance Learning in Clinical MedicalGeraldine Junchaya CastillaNo ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal Tract PDFDocument3 pagesGastrointestinal Tract PDFAlexandra Suan CatambingNo ratings yet

- "Unadulterated" - The Organic and Ethnic - For Vegetarians and Non-VegetariansDocument21 pages"Unadulterated" - The Organic and Ethnic - For Vegetarians and Non-VegetariansShilpa PatilNo ratings yet

- Physical, Biology and Chemical Environment: Its Effect On Ecology and Human HealthDocument24 pagesPhysical, Biology and Chemical Environment: Its Effect On Ecology and Human Health0395No ratings yet

- SyllabusDocument2 pagesSyllabusPrakash KumarNo ratings yet

- Quality Control Argex 0032/32.50.15.08 4/10 MM EN 13055: EN 15732 NL BSB K73820/01 (1/01/2004)Document1 pageQuality Control Argex 0032/32.50.15.08 4/10 MM EN 13055: EN 15732 NL BSB K73820/01 (1/01/2004)joe briffaNo ratings yet

- Alabama Religious Exemption AdvisoryDocument1 pageAlabama Religious Exemption AdvisoryABC 33/40No ratings yet

- Income Taxation Module Compilation FinalsDocument107 pagesIncome Taxation Module Compilation FinalsJasmine CardinalNo ratings yet

- Substation Off Line and Hot Line CommissioningDocument3 pagesSubstation Off Line and Hot Line CommissioningMohammad JawadNo ratings yet

- Cockerspaniel Pra CarriersDocument28 pagesCockerspaniel Pra CarriersJo M. ChangNo ratings yet

- 1-A Colored Substance That Is Spread Over A Surface and Dries To Leave A Thin Decorative or Protective Coating. Decorative or Protective CoatingDocument60 pages1-A Colored Substance That Is Spread Over A Surface and Dries To Leave A Thin Decorative or Protective Coating. Decorative or Protective Coatingjoselito lacuarinNo ratings yet