Professional Documents

Culture Documents

PsychologyDevelopingSocieties 2014 Gala Kapadia115 41

Uploaded by

Shaurya KapoorOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

PsychologyDevelopingSocieties 2014 Gala Kapadia115 41

Uploaded by

Shaurya KapoorCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/274991108

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood in an

Indian Context: Views of Emerging Adults and Middle Adults

Article in Psychology & Developing Societies · March 2014

DOI: 10.1177/0971333613516233

CITATIONS READS

10 2,211

2 authors:

Jigisha Gala Shagufa Kapadia

The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda

3 PUBLICATIONS 16 CITATIONS 27 PUBLICATIONS 121 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

PhD thesis View project

Adolescent-parent relationships: Indian cultural perspectives View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Shagufa Kapadia on 03 August 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Article

Editor’s Introduction 115

Romantic Love, Psychology and Developing Societies

26(1) 115–141

Commitment and

© 2014 Department of Psychology,

University of Allahabad

SAGE Publications

Marriage in Emerging Los Angeles, London,

New Delhi, Singapore,

Adulthood in an Indian Washington DC

DOI: 10.1177/0971333613516233

Context: Views of http://pds.sagepub.com

Emerging Adults and

Middle Adults

Jigisha Gala

M.S. University of Baroda

Shagufa Kapadia

M.S. University of Baroda

Abstract

The article focuses on issues of love, marriage and commitment dur-

ing emerging adulthood, a life phase which is increasingly prominent in

urban India owing to its global factors. In-depth and open-ended ques-

tionnaires and interviews of 110 respondents, comprising 80 emerging

adults, 40 women and 40 men; and 30 middle aged adults, 15 men and

15 women having children between 18 and 25 years of age were con-

ducted to (i) unravel the social beliefs and attitudes towards romantic

love, commitment and marriage and factors that shape these beliefs and

attitudes, (ii) understand the importance of commitment in conceptual-

ising romantic relationships and (iii) examine the generation and gender

differences in the concepts, beliefs and attitudes. Findings reveal that

even when the emerging adults are open to experimentation before

marriage, the ultimate goal of romantic relationship is to establish a

long-term relationship culminating into marriage.

Address correspondence concerning his article to Jigisha Gala, Assistant

Professor, Department of Human Development and Family Studies,

M.S. University of Baroda, Fatehgunj, Baroda-350002. E-mail: g.jigisha@

Environment and Urbanization Asia, 1, 1 (2010): vii–xii

gmail.com

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

116 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

Keywords

Emerging adults, romantic relationships, marriage, commitment, Indian

context

Formation of intimate relationships is an important developmental task

and also an integral part of identity formation during emerging adult-

hood. Emerging adulthood is a term coined by Arnett (2000) to indicate

the lengthening age span of ‘adolescence’ to include individuals in the

age range of 18–25 years. As a result of increasing affluence of the socie-

ties all over the world, the youth of the societies are free from responsi-

bilities of productive engagement and contributions to the economies as

well as free to explore alternatives in areas that are important markers of

adult life, viz. love and work. It is a phase of life which is highly unstruc-

tured by social institutions (Arnett, 2004, 2006). In response to the mul-

titudinous changes of globalisation, emerging adulthood, as a

developmental phase, has become evident in many urban parts of the

Indian society (Kapadia, Bajpai, Roy and Chopra, 2007; Seiter and

Nelson, 2010). There is a clear discontinuity in transition to these adult

roles in several segments of ‘modern’ India because of the increased

opportunities and need for higher education and career development.

The individuals are neither adolescents nor young adults; therefore, a

transitional phase of emerging adulthood is becoming evident.

During emerging adulthood, questions related to finding a ‘soul mate’

or life partner, somebody whom one can ‘count on’, somebody who

makes one feel special and also somebody who is so special that one is

ready to ‘make a commitment,’ abound. This article unravels the nature

and meaning of commitment in a romantic relationship. Is it a commit-

ment to get married to only X or does it mean finding an object of one’s

deepest care and concern and at the same time experiencing reciprocity

by being an object of someone’s deepest care and concern? The use of

the word ‘commitment’ accommodates several variations, even within

the Western culture ranging from the specific long-range goals that a

couple sets and tries to meet whether it is exclusive or only primary to

one person, whether it is forever or only ‘as long as it can work,’ whether

it is unconditional and similar other concerns (Delaney, 1996).

In the Indian context commitment may not be limited to the mutual

fulfilment of the couple but will extend to include all the family members.

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 117

The Hindu marriage vows or the Saptapadi1 invoke the gods to bless not

only the couple and the family but also the whole existence in totality.

The article also examines the societal beliefs and attitudes pertaining to

romantic relationships of emerging adults with reference to commitment

and marriage in the Indian context.

A context is shaped by its historical and philosophical backgrounds

and by the changes taking place currently at the global level. India serves

as an interesting context to study romantic relationships because Indian

mythology (e.g., Mahabharata), Sanskrit literature (e.g., Puranas,

Vatsayana’s Kama Sutra, Bhartruhari’s Shringar Shatak) and certain

schools of Indian philosophy (Carvaka, Tantamarga, Shaivamarg,

Shaktamarga, Bhaktimarga) hold one of the most liberal, permissive and

dispassionate views of human sexuality and love as well as individual

freedom. Yet, apparently, in the Indian culture romantic relationships are

a taboo. How this taboo is dealt with in the contemporary rapidly chang-

ing Indian society and its impact on traditional markers such as marriage

and parenthood is a relevant issue.

Emerging Adulthood, Romantic Relationships

and Commitment

Although emerging adulthood is not propounded as a universal develop-

mental stage, Arnett (2000) argues that the current era affords for most of

the youth the luxury of emerging adulthood. The factors, which con-

strained the young people historically ranging from specific gender roles

and poor economies that needed the youth to be ‘productive,’ no longer

hold true for most urban places in the world. Increasing affluence, focus

on education and availability of various career options for both men and

women and technological revolution in contraceptive methods have led

to the postponement of marriage and parenthood, which were the tradi-

tional markers of adulthood across cultures. These trends are visible in

the urban cities of contemporary India, including the city of Baroda,

Gujarat (Chopra, 2011) which is the context for the present study.

Romantic relationships provide a context where emerging adults can

discover aspects of their own selves such as what attracts them, what

makes them attractive or otherwise to their partners and what kind of

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

118 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

person could be their ‘soul mate’ (Arnett, 2004). In general romantic

love is a concept associated with the Western culture and arranged mar-

riages are associated with the East, especially India. However, many

theorists, including proponents of the ethological perspective, propose

that romantic attachment is universal to the human animal and in fact

inevitable for the survival of the species. Fisher, Aron and Brown (2006)

talk about three distinct and yet inter-related brain systems which are

responsible for sexual drive, romantic love and attachment. While sexual

desire helps individuals to seek a range of mating partners, attraction

helps individuals to stay with each other long enough to fulfill their

parenting duties. Both hormones and monoamines trigger, stimulate and

facilitate the three brain systems. Therefore, developing a romantic bond

and entering into a committed relationship are cross-cultural universals.

Even when our species is hardwired for romantic love, this phenom-

enon has not always been the basis for long-term commitment and par-

enthood. Human societies have been organised to meet practical purposes

rather than pursue romantic ideals. It has been noted that romantic love

is influenced by a number of contextual factors such as affluence, gender

power parity, education and technological advancement. For example,

Simpson, Campbell and Berschied (1986) report that romantic love,

which is now the ‘only right basis of marriage’ in the West, is a relatively

recent proposition. The authors replicated a survey conducted in the mid-

1960s for American college going men and women using Kephart’s

(1967) scales to determine the association of romantic love as the basis

for marriage and as an important factor for maintaining a marriage. They

found that since the 1960s, more college going men and women have

viewed love as a critical factor determining a long-term commitment

owing to dramatic social changes such as the status of women. Therefore,

the global factors that have given birth to the new life phase of emerging

adulthood have also made it possible for these individuals to pursue rela-

tionships which are based on egalitarian values. In the changing Indian

context, it would be interesting to find out the importance of love as a

prerequisite to marital commitments vis-à-vis for maintaining a

marriage.

Recent studies conducted in China reveal that Chinese scored higher

on romantic beliefs scales and on certain dimensions of romanticism

scales when compared to samples from North America (Sprecher and

Morn, 2002). They also found that Chinese were both more idealistic and

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 119

practical in the approach to love beliefs than the North Americans. The

researchers attributed this trend to various social and cultural changes

that have taken place in China after it embraced the market economy.

Romantic love was no longer treated as a ‘bourgeois’ sin punishable with

years in prison. Young men and women now have increasing freedom to

choose their partners. Thus, both emerging adulthood and romantic rela-

tionships appear to be a phenomenon of an economically affluent,

socially liberal and non-discriminating society.

Romantic Relationships in the Indian Context

Little research has focused on how romantic relationships manifest in

different cultural contexts. To understand the paradox of restrictive

norms for forming opposite sex relationships in contemporary India and

the liberality of ancient and medieval India, a review of romantic love in

ancient India through medieval ages leading to the contemporary context

is presented here.

Perspectives from Ancient and Medieval India

In India, romantic love has found its place in various schools of Indian

philosophy. Indian philosophy has been aptly summarised by Mahadevan

as ‘a philosophy of values’ (p. 326 as in Goodwin, 1955), the highest

value being individual’s freedom to work towards self-realisation and

realise the freedom of all (any kind of) bondages. The term ‘romantic

love’ denotes the highest possible ‘ideal’, which when aspired by indi-

viduals would lead them to understand their own nature, the highest form

of consciousness. Indian epics and mythology have ample examples that

depict the glory of romantic love as well as its dangers and tragedies

(Punja, 1992).

Love and Marriage

Counter-intuitive as it may sound, love and marriage have never been

treated together in the Indian context. Observations from remote antiq-

uity suggest that the God of love (Kamadev) and that of marriage are

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

120 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

different (De, 1959). While marriage was treated as a social duty, a social

ideal, love was celebrated as a personal ideal and was thought to be pos-

sible only when it was free of all compulsions. Therefore, marriage was

looked upon as a matter of arrangement for political alliance and eco-

nomic exchange and was founded on the ideal of duty (dharma). Finding

a partner through selection (varana) or through gift of a maiden

(Kanyadan) was regarded as higher forms of marriage in the sastras.

Therefore, marriages were usually arranged except the Gandharva2 mar-

riages, the only form of marriage, which entailed pre-marital courtship

and was sanctioned by the sastras (Ali, 2002). Gandharva marriages

were rare and appeared mainly amongst the Kshatriya classes (Ali, 2002;

De, 1959). Romantic love was considered an evolved form of pairing as

in Ali (2002),

The gandharva marriage, according to Vatsyayana, was the superior form

because it was attained without much difficulty, without a ceremony of ‘selec-

tion’ (avarana), and was based on mutual affection or attachment (anuragat-

makatvat) which was said to be the ‘fruit’ of all marriage in any event (p. 129,

Kamasutra 3.5. 29–30).

Some scholars have argued that kama and rati (related to pleasure

arising from sexual union) is different from anuraga (affection) or bhakti

(devotion). In fact, most of the religious texts have admonished kama

and associated it with the downfall of the yogis (yogabrashta). The

‘ascetic life’ of conquering the senses or the lower self to attain freedom

from desire, passion and attachment, would sound incredible for a ‘life-

affirming’ westernised mind. But, in the Indian context, from the stand-

point of civilisation and sanskritisation, the highest pleasure is attaining

to the infinite and the love for the finite is only instrumental to that pur-

pose (Radhakrishnan in Goodwin, 1955). Therefore, the emphasis on

self-discipline can also be read as ‘…the proper enjoyment of pleasure is

not conceived of in opposition to self-discipline and mastery of the

senses, but as a proper function of it’ (Ali, 2002, p. 212).

Contemporary Indian Context

With the passage of time, the fine balance in understanding that the mate-

rial and the spiritual are not two but one was lost. There was too much

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 121

stress on hypergamy, caste and virginity. Although, in the Indian tradi-

tion, ‘love’ is a value for which one is ready to die, a value beyond one’s

life, in practice, there is an apparent disjunction. As Kapadia (1998) has

observed, romantic love seems acceptable only if it eventually leads to

marriage and that too, if the mate is from an appropriate class, caste and

religion. Today, once again, India seems to be moving towards less strin-

gent attitudes towards ‘love’, especially in the urban areas. Netting

(2010) reveals that upper class Indian youth creatively overcome the

apparent dichotomy by evaluating the ‘ideoscapes of individualism and

romantic love through the lens of their Indian heritage’.

With changes leading to extended periods of education, increase in

education of girls, better opportunities of interaction between emerging

adult men and emerging adult women, various career options, role con-

fusions, increased legal age of marriage, the relationship establishing

patterns have also changed. The changes in the ICT (Information and

Communication Technology) affect the lives of young individuals in

profound ways. As mentioned earlier, the transition periods are length-

ened due to changes in the institutional structures, educational require-

ments and delaying full-time occupation and also marriage and

childbearing. Consequently this also affects the ways in which individu-

als relate to each other. More time spent in educational settings, wider

social network and technological advancements such as the internet

increases the opportunities to interact with the opposite sex peers (Larson,

Wilson, Brown, Furstenberg and Verma, 2002). The internet creates a

‘social space’ for young individuals that provides numerous choices for

forming and maintaining social networks (Mortimer and Larson, 2002).

Also, increased anonymity in larger cities facilitates the growth of

romantic relationships.

Research Questions

Notwithstanding the contemporary global context which makes it easier

for emerging adults to experiment with their relationships and gives

them the freedom to choose their partners in their own terms, some cul-

tural ideas are not only resistant to change but also upheld as a value.

Commitment in relationships is one such ideal. It is interesting to study

commitment in the context of romantic love in a culture with a long

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

122 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

tradition of marriage as a means to achieve practical ends such as family

cohesion rather than love. While an arranged marriage need not have

love as its meaningful end, does romantic love need to have marriage as

its ‘logical’ end? Does the Indian society approve of these relationships

for their own sake or are they considered legitimate only if the romantic

partners have marriage on their mind? What are the social attitudes and

contextual factors towards romantic love, commitment and marriage?

And are there any age and gender differences in these attitudes?

Method

The study adopted a mixed methods research design. It is a phenome-

nography with an interpretative stance. Multi-methods were used to

understand the phenomenon of romantic love and commitment from

multiple perspectives. Open-ended questionnaires and interviews

included questions to elaborate and express one’s views at length. The

rating scales help to further concretise the data.

Sample

The participants of the study comprised two groups of college going

emerging adults in the age range of 18–25+ years: (i) currently involved

in romantic relationships and (ii) not currently involved. It also included

middle adults in their 50s–60s+ years, having children in the age group

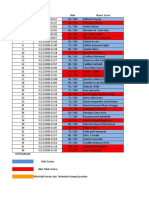

of 18–25 years. Data were collected in two phases as indicated in Figure 1

that displays the sample size and distribution across the two phases of

the study. Table 1 indicates the rationale for selecting the different

subgroups.

Measures

All the measures were developed by the investigators and the content

was validated by five experts from related fields. The study used multi-

ple methods and sources in order to ascertain greater validity to the data.

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 123

Sample Size and Distribution (N =110)

Phase 1 (n = 80) Phase 2 (n = 30)

EAF (25) + EAM (25)= MAF (15) + MAM (15)= RRF (n = 15) RRM (n = 15)

EA (n = 50) MA (n = 30)

Figure 1. Sample Size and Distribution

Source: Authors.

Notes: EAF – Emerging Adult Female; EAM – Emerging Adult Male; MAF – Middle Adult

Female; MAM – Middle Adult Male; RRF – Emerging Adult Female Currently

Engaged in a Romantic Relationship; and RRM – Emerging Adult Male Currently

Engaged in a Romantic Relationship.

Table 1. Sample and Rationale

Participants Rationale

Why emerging adults? The purpose is to understand romantic

relationships from the perspective of emerging

adults as the study is concerning them

Why individuals presently They provide information based on their

involved in romantic experience and hence the data collected are of

relationships? phenomenological value

Why individuals who are Information from this group will place the

not currently involved phenomenon in context as it will report the

and may have no past ‘outsiders’ perceptions and observations, that

experience either? is, providing societal perspectives

Why middle adults? To understand relationships in India, it is vital to

take into account the views of the parents. To

ensure the privacy of the emerging adults (EAs),

it was decided to include middle adults who had

children in the age group of 18–25 years and

not necessarily the parents of participating EAs

Why equal representation To capture the voices of both genders and to

of men and women? compare the impact of the phenomenon on

both groups

Source: Authors.

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

124 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

While Table 1 depicts the need for understanding the phenomenon from

different sources, Table 2 presents the tools and domains covered corre-

sponding to the different objectives.

1. Demographic form: Information pertaining to age, education,

occupation and income was sought for the purpose of socio-

demographic profiling of the respondents.

2. In-depth and open-ended questionnaires and in-depth interview

guideline: Questions were related to the domains of concepts,

beliefs and experiences of romantic love and commitment, nature

of their relationships, societal attitude towards relationships which

had no long-term commitment and importance of parental and

familial considerations in making long-term commitments.

A component of Kephart’s (1967) Love–Marriage connection

scale has been included after re-wording and extending to make it

more suitable for the purpose of the present study. For example,

the original item was:

If a boy (girl) had all other qualities you desired, would you marry

this person if you were not in love with him (her)?

Table 2. Objectives, Tools and Domains

No. Objectives Tools Domains Covered

1 Study the concept of Open-ended questionnaire Concept of romantic

romantic relationship for emerging adults love/romantic

and its connection Open-ended questionnaire relationships, meaning

to commitment and for middle adults of commitment

marriage amongst the Love marriage

emerging adults and connection

middle adults in an

Indian society

2 Study the impact of Open-ended interview Meaning of

quality of romantic guideline for emerging commitment

relationship with adults currently engaged in Level of commitment

reference to a romantic relationship and its relation to

commitment on Rating scale for emerging happiness

perceived happiness adults currently engaged in

a romantic relationship

Source: Authors.

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 125

(Yes/No)

It has been changed to make it more open-ended to understand the

reasons. For example,

If a man (woman) had all other qualities I desired, I would marry

this person even though I was not in love with him (her).

(Agree/Disagree/Undecided), Why?

3. Rating scales: The 5-point rating scales focused on the level of com-

mitment and happiness in the current relationship. The rating scales

were administered only in the phase 2, that is, for emerging adults

engaged in a romantic relationship at the time of data collection.

Analysis

Qualitative and Statistical Analysis

The unit of analysis is ‘utterances’ of the participants from in-depth

interviews and notes of respondents from the questionnaire. The data

from each participant are viewed as a whole rather than coding them

after taking snapshots of particular questions and assigning them to

categories. For the yes/no type questions frequencies were calculated.

For example, ‘Would you like to marry your current romantic

partner’?

• Pearson’s correlation was used to identify relationships between

happiness and commitment.

• The t-test was used to analyse data from rating scales and for gender

comparisons.

The two forms of analysis help in integrating the data to better under-

stand a problem. The quantitative data are many a time congruent with

the qualitative data and at times challenge the presumptions generated

through the qualitative self reports.

Results

The results are organised under three main sections. The first section

presents the context of the present study and the socio-demographic profile

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

126 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

of the participants. The second section puts forth the factors that are

shaping romantic relationships in the contemporary Indian context. Here

responses of all the subgroups of participants represent the societal per-

spectives. The data from the emerging adults currently engaged in a

romantic relationship depict their experiences of love and commitment,

which give the phenomenological value to the data. In the last section the

social beliefs and attitudes towards romantic love, commitment and mar-

riage are portrayed which again are a representative of the responses of

all the participants.

Context of the Present Study

The context for the present study is a mid-sized growing city Baroda in

the state of Gujarat. Baroda or Vadodara has been known as the sanskari

nagri (cultured city) of the state, as it emphasises on university education

for both girls and boys. The Maharaja Sayajirao Gaekwad III in 1875 had

introduced many reforms including a focus on girl’s education and adult

education and the benefits of which we reap even today. Baroda’s cul-

tural life is very dynamic as it is remarkably cosmopolitan. Baroda amply

serves as an example of a modern urban Indian city. It is remarkable for

the ‘mobility’ that it allows its youth, especially the girls. Here the term

mobility is used in a broader way encompassing not only geographical

mobility but also mobile technologies. Having a personal two-wheeler

vehicle and a mobile phone and easy and affordable accessibility to

internet are very common for the young. The changes and effects of

mobility on emerging adults include the opportunities to develop inti-

mate relationships, maintaining secrecy and privacy, satisfying the

intrinsic needs of ‘contact’ and at the same time freeing them from physi-

cal proximity and spatial immobility.

Profile of the Participants

Fifty two per cent of the emerging adults and their romantic partners

were under graduates and the remaining were graduates, all currently

pursuing education. Only 6 per cent of the romantic partners of the

emerging adult women were doing a part time job along with their studies.

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 127

Middle adults, men and women, were mostly graduates; only 17 per cent

were postgraduates. Only two middle adult women had not been to col-

lege. All participants reported that they were either from middle or upper

middle income groups.

Factors Shaping Romantic Relationships in the Contemporary

Indian Context

As shown in Figure 2, unanimously, all respondents have unanimously

revealed that the visibility of romantic relationships has increased greatly

in the contemporary context. A middle adult man says, ‘The manifesta-

tions may be different but they are as primordial as human beings’. Their

major contention is that the quantitative increase in heterosexual pairing

Media and

Technology e.g.

Globalization Movies,

and Magazines, Porn,

Influence of Internet,

Western Contraceptive

Weakening of Culture revolution

Family Ties, Peer

Pressure,

Increased Changes in

Acceptance of Societal

Love Marriages, Values

Early Financial

Higher Education,

Independence

Freedom to Girls,

Conducive

Enviroment for

Changes in Cross Sex

Life Style Interactions,

Increased Stress

and Less Support

from Parents and

Family

Figure 2. Reasons for Rise in Romantic Relationships in the Contemporary

Context

Source: Authors.

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

128 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

does not fall under the category of romantic relationship, because nowa-

days people lack sincerity, which is integral to a romantic bond. A girl

expresses, ‘Now-a-days it is more attraction and infatuation among the

youth rather than romantic love. Today love means “to sleep” with some-

one’. Similarly a middle adult man echoes, ‘Today it’s all about sex –

cheap sex. No understanding, no intelligence, all materialistic. Where is

the romance?’

As depicted in Figure 1, many reasons have been reported for the rise

in romantic relationships in the contemporary context. Sixty per cent of

the emerging adult women and 40 per cent of the middle adults believe

that changes in the value systems and life style are significant factors.

Many feel that egalitarian values and individual freedom to make choices

are valued currently ‘This is because of the change in their way of think-

ing of the people. They are now quite straight forward and they believe

that there must be a very special friend in their lives’, says a girl. On the

other hand, others feel that the materialistic and sensual curiosity is val-

ued these days over commitment and sincerity and relationships are used

as a means for pomp and show. A college going girl quips, ‘People espe-

cially college student, fall in love just to say being “in”, just to flaunt

having a boyfriend or girlfriend’, and a middle adult man feel that is

‘dekhadekhi’—meaning wanting to compete with the neighbour.

More emerging adults than middle adults felt that the modern ‘stres-

sors’ and media make it imperative to seek comfort in a romantic rela-

tionship. Modern day stressors are perceived as stemming from a change

in family structure from joint to nuclear and also a change in parent–

child relationship where parents spend less time with their children and

hence having someone special becomes very important. This idea has

been summarised by a boy as follows, ‘Modernization, more influence of

western culture, exploring and adventurous kind of nature, more expo-

sure to vulgarity through media, magazines, sex education, lack of com-

munication with family members (generation gap), increased level of

stress and also sometimes peer pressure accounts for this change’.

More emerging adult men compared to middle adults and emerging

adult women reported that increased opportunities to interact with oppo-

site sex partners and increasing freedom to emerging adult women pro-

vide a conducive environment for the formation of romantic relationships.

For example, ‘Nowadays there is more opportunity of meeting the oppo-

site sex at a single place and girls are getting more freedom for education

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 129

and jobs’. The emerging adults and women reported that in the present

times emerging adults prefer to choose their own partners. For instance,

a middle adult woman says that romantic relationships are increasing

because emerging adults want ‘…to have a self-blessed life and

companion’.

Although the respondents believe that the visibility of ‘romantic’ rela-

tionships in the Indian society has increased remarkably, many of them,

especially the middle adults, believe that the current relationships lack the

‘romantic’ element—the depth and beauty which was present in their

times. Overall, however, majority of the emerging adults and middle adults

perceive that it is because of factors associated with globalisation that this

innate phenomenon can be more freely expressed in the present times.

Commitment in Romantic Love

Conceptual analysis of what is meant by romantic relationship indicates

that 31 per cent of all respondents believed that romantic love is another

name for commitment. This shows that only a few of them included

commitment as one of the defining features or a prerequisite for roman-

tic love. Yet, when the phase 2 participants, emerging adults who had a

romantic partner, were asked whether they were committed to marry

their romantic partner, the answer was an emphatic ‘of course,’ for 77 per

cent of the respondents. Of the 23 per cent who said no, 15 per cent were

emerging adult men. The emerging adult women, who said that they

were not committed, did not believe in marriage or said that love is

beyond all commitment. Emerging adult men did not cite any reason;

they said they have not yet considered it. A few also said that commit-

ment was subject to parental approval. In the words of a boy ‘Yes I would

like to marry her, yet we know we cannot marry, because I don’t think

that my parents can accept my relationship and I do not want to hurt

them… and that’s okay with her, as she too will not go against her par-

ent’s wishes’. The parent factor featured commonly in most responses.

Of the 77 per cent of the emerging adults who were romantically

involved, only 13 per cent believed that they would get married to their

romantic partner even in the face of adversity. For example a girl declares,

‘Whatever happens I will try to convince my parents. But even if they do

not get convinced, I would marry him. As the time goes they would

agree… Ultimately I have to convince my father because he is the one

who is going to raise all the objections.’

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

130 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

For 87 per cent of the emerging adults their romantic relationship was

a beautiful journey, a road that may lead to nowhere, whereas for others

it was a power that would help them overcome any obstacle that came in

their way of uniting with their partner. Therefore, a loving commitment

and sincerity in romantic relationship may not necessarily lead to a mar-

riage, even though a long-term commitment in romantic love is desirable

by the emerging adults and praised by the middle adults.

When emerging adults were asked whether it is alright to have more

than one romantic experience before marriage, majority of them

responded in the affirmative, with more emerging adult women endors-

ing this belief. In contrast no major difference in the number of emerging

adult women and emerging adult men who have reported that the current

relationship is not their first romantic experience was found. At the same

time emerging adults are not in favour of having simultaneous relation-

ships. They feel it is alright to enter into another relationship after the

first is over. They also added that changing relationships should not

become a habit, but entered into only if it helps one to learn from one’s

mistakes, to understand why their relationships are breaking and also to

make a better choice for a life partner. As put forth by a girl, ‘Yes, if you

are getting in and out of relationships, you come to know where you are

going wrong, why all these relations are not lasting. So you get to intro-

spect. So you can have a more successful marriage’. And a boy contends,

‘Yes, but you should never betray anyone. If you don’t like someone then

you can leave, but not betray.’ The other individuals felt that ‘It is better

to think hundred times before entering into a relationship rather than

breaking up later’. However they clarified that they were not against

people who opt for break-ups and new relationships.

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage

As indicated in Table 3, 82 per cent respondents have attributed great

significance to commitment in a romantic relationship. The reasons for

the same however go beyond the security factor. Most of the time, com-

mitment is regarded as important because the respondents believe that

the romantic partners know each other in and out, and therefore, they

could make great spouses. As a boy believes, ‘They begin to know each

other so well, their likes and dislikes etc., even without feeling the need

to tell each other, so they should get married or else it is like as if one

soul is divided into two’. Commitment was also viewed significant

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 131

Table 3. Importance of Commitment to Marry in a Romantic Relationship

(N = 80)

Categories Illustrative Verbatim Comments

Commitment very important (n = 65)

‘Commitment is the only thing on which the whole love life is based… For me

everything is commitment, love without commitment stands nowhere’

‘If this quest culminated into a long term relationship on its own and not out of

force then that is the goal of finding such a companionship rather than jumping

relationships and going through same kind of rut and trauma’

‘If one cannot live up to one’s commitments, the betrayed one may mentally suffer,

emotionally it is a big loss and may drive to extreme steps’

‘If no commitment is there then you are just using someone’

Commitment is not important (n = 15)

‘First one should know each other to understand each other’s life, financial conditions

and future perspectives, commitment can come later’

‘Life in its weird way throws up situations where parting of ways may be inevitable.

To break all relationships for the sake of one at such a situation would be a stupid

idea. Commitment starts only after marriage’

‘… true love is beyond any bindings. It is an enduring experience’

Source: Authors.

because they believe that breaking up with someone whom one has cher-

ished can cause serious mental and emotional strain on individuals. ‘If a

relation breaks then both partners tend to be in a different situation and

at times take steps which one should never take.’ Very rarely societal

reasons were cited for the remaining committed in a relationship. Also

most of the emerging adults believed that commitment should come on

its own and it is up to the two partners to decide. For example a girl says,

‘For me commitment is quite important because I think when you enter

into such a relationship after certain maturity commitment comes on its

own. But I don’t disrespect people who are not committed because every-

body has their own requirements from this relationship’. For some

emerging adults marriage seemed the only way to be with the romantic

partner as other alternative arrangements are uncommon in India. A boy

said, ‘…because in India, live in relationships are not common’.

Among those for whom commitment is irrelevant, they talked about

being in the present, knowing each other well and that love is the be all

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

132 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

and end all and does not require a legal guarantee. For example a middle

adult man reported, ‘If you are mature enough then the existence of com-

mitment is not needed. The feeling is so supreme that it is on the top and

you don’t need anything on the top of top.’ At the same time they also

said that one cannot keep jumping from one relationship to another, as

shared by a middle adult man, ‘Because how many relationships can you

have, it should be a long term relationship, maximum two otherwise, it

becomes a habit, it’s no good’.

There was no significant effect for gender, t(28) = 1.17, p < 0.05.

However, Pearson’s correlation showed significant positive correlation

between the domain commitment and the domain happiness. The two

variables were strongly correlated for emerging adult men, r(28) = 0.49,

p < 0.005, when compared to the emerging adult women, r(28) = 0.29,

p < 0.005.

Table 4 captures the importance of love in a committed relationship

like marriage. The respondents had to choose from the options Agree/

Disagree/Undecided with the following statement and also share reasons

for their opinions:‘If a man/woman had all other qualities I desired,

I would marry this person even though I was not in love with him/her’.

Table 5 depicts the importance of love in maintaining a marriage. The

respondents had to choose from Agree/Disagree/Undecided with the fol-

lowing statement and also state reasons for their opinions: ‘If love has

Table 4. Love is Significant for Entering a Marriage (N = 110)

Agree/Disagree/Undecided

Agree (n = 45)

‘I am a firm believer that if your partner is good and has good qualities you are

bound to respect him and eventually love will happen’

‘On the condition that he loves me. It’s important to marry a person who loves you’

Disagree (n = 44)

‘In a broader perspective or long term perspective, love is more important not

qualities’

Undecided (n = 21)

‘Because one has to be practical at times as well as one has to be emotional. I am

confused about this aspect’

Source: Authors.

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 133

Table 5. Absence of Love: An Adequate Reason for Dissolving a Marriage

(N = 110)

Agree/Disagree/Undecided

Reasons/Conditions

Agree (n = 43)

‘If there is marriage but not love, is there anything left? So might as well disappear

from each other’s life’

‘When both the spouses can independently pull their lives alone and have the

support of families, relatives and society’

Disagree (n = 42)

‘One should make proper efforts and solve the problems and difference. Give proper

time to their partner to understand each other. At last if it is not working then they

should get apart’

Undecided (n = 25)

‘Break up, provided no one depends on us or is affected by our breakup’

Source: Authors.

completely disappeared from a marriage, I think it is probably best for

the couple to make a clean break and start new lives’.

Love-marriage Connection

Tables 4 and 5 show the value and significance of love for entering into

and sustaining a marriage. The respondents were asked whether they

would marry a person who had all the qualities they desire even though

they did not love that person. While the answers appear to be favouring

love only about 40 per cent of the times, the actual picture is slightly dif-

ferent. Even when people choose the option of entering into a marriage

without falling in love first, they do so because they firmly believe that

love is a response to the qualities embodied in an individual and so the

desired qualities will lead to love or at least the person is a good candi-

date for a perfect partner. One girl felt that she would marry a boy if he

loves her even though she may not love him, because feeling loved is

beautiful and love is so attractive that it will make her fall in love with

him later. Few respondents also reported that love happens as one stays

with a partner for some time. In words of a middle adult woman, ‘Love

is guarded by time. As time passes one falls in love’. This is also echoed

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

134 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

by some of the emerging adults. As a boy puts it, ‘Falling in love is just

a matter of time if all the qualities are present’ and a girl says ‘According

to me, love grows with time, so I will understand and one day will be in

love like any other love relationships’.

The responses in Table 5 align well with the concept of love in India

which requires one to let love develop as time passes or work out ways

to discover love and harmony if it did not exist before.

Thirty per cent of the responses focused on the potential a person with

desired qualities had to prove to be a good partner. Some emerging adults

said that the quality they desire most is the understanding between the

two and that is more important than love. Some also felt that it is an

indication from destiny. In the words of a boy, ‘Because I would believe

that she is made for me and because of god’s wish, her meeting with me

happened’. Other emerging adults felt that good opportunities knock

only once and so they will treat this as a match as in arranged marriages.

According to a boy, ‘There are so many things on earth except love and

compromise is one of those things. If I don’t get love in obvious way so

I will try to get it by compromise’. The desperation to ‘get’ love, or some-

thing ‘love like’ through a compromise also indicates the importance of

love. Further, mostly emerging adult men focused on the match being

acceptable to their family, while emerging adult women are concerned

about expecting their potential partner to respect her family members.

Nevertheless, majority of the emerging adults felt that love is neces-

sary before one decides to get married as otherwise the relationship will

not last in the long run. As echoed by a romantically involved emerging

adult girl, ‘There can be thousands of good qualities but if you don’t love

the person or if you are not comfortable with that person you cannot

spend your life. If there is no understanding and if that feeling not there,

then there is nothing’.

In this sense there is not much difference whether a person agreed or

disagreed to marry a person possessing all desired qualities but was not

in love with the person, because the answers vary based on the concepts

of love and desired qualities. If the desired qualities are the ones which

are based on the value systems of the individual and on mutual compat-

ibility, and not just on physical appearance, people felt that love will

happen sooner or later so one can marry the person. On the other hand,

love was looked upon as the most desired value, because if one was in

love with a person then everything becomes desirable and it is possible

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 135

to live together. A girl explains, ‘Love makes you forget the qualities that

you actually desire, loving the person is more important because there

are some qualities which are not nice in a broader perspective or long

term perspective so love is more important, not qualities’. And perhaps,

owing to this, 25 emerging adults were undecided and said that spending

more time to understand each other could be a better option.

Most of the emerging adults also believe that love is very important to

maintain a marriage. Despite that, deciding to dissolve a marriage

because love seems to have disappeared is just not easy. Many of them

felt that love cannot just disappear and a relationship needs to be worked

upon and sustained as far as possible. As expressed by a girl, ‘…because

love never disappears, it is we who start ignoring the love. And one can

always have a new beginning.’ Unless it gets to the point when it becomes

impossible to live together, most of them were not readily in support of

a divorce. They felt it would create more issues and problems rather than

making life better, for example problems at financial, emotional, social

and personal level. Moreover, responsibility towards children and other

societal and financial aspects need to be considered before deciding to

dissolve a marriage. This was echoed across gender and generation.

Data from the rating scale comparing responses of emerging adult

men and women in the domains of commitment and happiness showed

no significant effect for gender, t(28) = 1.17, p < 0.05. However, Pearson’s

correlation showed significant positive correlation between the domain

commitment and the domain happiness. The two variables were strongly

correlated for emerging adult men, r(28) = 0.49, p < 0.005, when com-

pared to the emerging adult women, r(28) = 0.29, p < 0.005. This finding

is in contrast to what was intuitively reported in qualitative data in which

it was perceived that commitment was more important for the emerging

adult women. This finding reflects the need to use different measures to

understand a phenomenon, as what may be reported a largely held com-

mon belief may be very different from the lived experiences of emerging

adults.

Highlights of the Findings

Overall, sincerity is highly valued in a romantic relationship. Whether

one is committed to marry or not is a matter of what one wants the phe-

nomenon of romantic love to deliver, and this is the sense in which com-

mitment to marry is valued and praised, but not enforced. Commitment

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

136 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

is a matter of doing what is good and right for oneself, for the partner, for

parents and for all the others involved at large, depending upon several

factors and unforeseen circumstances. But in theory romantic love gets

the status of romantic only if it involves sincerity and commitment.

Experimentation for the sake of experimentation is not recommended by

the respondents. As far as a relationship teaches one something about

oneself and relationships, break-ups are acceptable. But, moving in and

out of relationships without thinking about long-term intimacy is consid-

ered a waste of time and at times a ruthless act against one’s own roman-

tic partner. Love as a precursor to marriage is more acceptable than

absence of love as a basis to dissolve a marriage.

Discussion

The construal of love on the basis of commitment has many shades. The

intuitive reports of respondents regarding the increased visibility of

romantic relationships in the Indian context and the attribution of the

cause to globalisation correspond with the ideas proposed by many

scholars including Arnett (2000, 2004). Yet, love without awareness

about one’s own self, love without sincerity, love without the foresight of

long-term consequences and love without commitment do not mean

much to emerging adults and middle adults in the urban Indian context.

On the other hand, the emerging adults who were currently engaged in a

romantic bond or had experienced one in the past, believed that romantic

relationship is a process of self-discovery. Security is not a value in itself,

but love is. Love is supreme and a relationship based on love (till it lasts)

needs no other legitimacy, let alone a ‘piece of paper’ called marriage

certificate. And for some emerging adults, experimenting in the contexts

of romantic relationships meant finding a ‘right partner’ to live their

entire life with. Therefore, even though the process does not begin with

commitment, it has to end if long-term commitment seems impossible.

The reasons could be personal or societal.

Even today, the ‘voices’ echo the supremacy of love as reflected in the

socio-historical context of the Indian ideology. Love inherently has a

quality of madness that appears impudent to the society. However, to the

Indian mind, whether it is of an emerging adult or a middle adult, frivolous

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 137

approach to these relationships is very disturbing. The stereotypes of

‘hooking up culture’ which stands for indiscriminate involvement asso-

ciated with emerging adult’s sexual relationships in the West (Lefkowitz,

Gillen and Vasilenko, 2011) are also evident from the responses in the

present study. While the respondents hold globalisation as responsible

for making the contemporary Indian society more conducive to form

romantic bonds, many feel that impulsive relationship choices based on

sexual attraction are a product of the westernisation of ‘our’ culture.

The middle adults as well as emerging adults felt that the romance is

missing from the ever increasing number of romantic pair bonds. When

they viewed the emerging adults’ romantic relationships just as a way of

experimenting sexually or to fill their empty materialistic lives with poor

alternatives such as ‘cheap’ sex with no concern for the partner involved,

they felt that ‘romance’ is getting a bad name. This concern is in line with

Abraham (2002) who has identified platonic ‘bhai-behen’ (‘brother–

sister like’), romantic ‘true love’ and transitory and sexual ‘time pass’

relationships amongst the unmarried youth from a low socio-economic

background in an Indian metropolis. The term ‘time pass’ meaning insin-

cere and frivolous relationships is along the lines of the Western proto-

type of ‘hooking up culture’ that no longer reflects the intensity or depth

associated with intimate relationships. The respondents feel that this is

neither ‘romantic’ nor a part of the Indian culture. Indian emerging adults

are however catching up with this materialistic approach and it is voiced

as a concern by the respondents. For example a middle adult woman puts

it, ‘Well, I think Indians are trying to accelerate steps to walk with west

but a romantic relationship can be had without the western way of

romantic relationship. A sense of curiosity, is a romance in itself’.

More than 50 per cent emerging adults have expressed the desire to

opt for either love marriage or marriage by self-selection. Yet, a substan-

tial number of emerging adults still prefer arranged marriage, many a

times fearing the intensity of romantic relationship or at times also

‘knowing’ that their parents would not accept a love marriage. The idea

about fulfilling parents’ expectations and the desire of not wanting to

‘hurt’ them without examining the correctness of such expectations is a

concern for both parent–child relationships as well as romantic

relationships.

Similar issues have been discussed by Netting (2010), where young

individuals who were forced by parents to leave their romantic partners,

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

138 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

felt that it would have been better had they stood by their own choices

rather than allowing their parents to make them feel guilty and thus con-

trol their lives. This finding also has implications for the cultural ideas

about ‘being loyal to parents’ and ‘respecting elders’ as a value in itself.

The sense of ‘owning’ a person in a close relationship, whether it is a

romantic partner or one’s own child, takes individuals farther from expe-

riencing acceptance, trust and intimacy that form the core of intimate

relationships. Another issue is that the emerging adults who are afraid of

taking a stand use ‘façade of loyalty to parents’ as a legitimate reason to

break up and avoid commitment.

Close relationships cannot be taken for granted. Overall, establishing

long-term relationships based on trust and commitment is considered an

important function of romantic relationships. Not only is marriage the

goal of romantic relationship but the ‘fruit’ of marriage, even when it is

arranged, is romantic love. Emerging adults can have a number of expe-

riences with romantic relationships before marriage; however, the focus

must be self-exploration or finding a suitable marriage partner rather

than making experimentation with relationships a life script.

Conclusion

Whether a romantic relationship is committed or not, it needs to be nur-

tured in order for it to contribute positively to the individual’s develop-

ment. The ideas pertaining to non-duality between body and consciousness

need to be revived from the ancient past of Indian thought that defined

romantic love as a response to the highest value. One need not move

from a repressive society to an indiscriminatingly liberal society as oth-

erwise again the consequences would be undesirable. Undesirable con-

sequences include inability to form lasting and fulfilling relationships.

The voices of the respondents can be aptly summarised by Siegel’s

(1978) commentary on Jayadeva’s Gitagovinda, ‘Sensual love seeks

meaning and significance in the eternity of the sacred; spiritual love

seeks meaning and impact in the immediacy of the profane’ (p. 4) or as

Mahadevan puts it, ‘it is not only the pleasure of the moment, sense-

pleasure, or the greatest amount of pleasure in this life that we desire, but

everlasting happiness’ (cited in Goodwin, 1955).

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 139

The concept of commitment in India is more about commitment to the

self in doing that which is right and good for not only oneself but for

everyone. Therefore, commitment is desirable and valued as it serves

functional purposes in a relationship and the society; however, it need

not become dysfunctional to individuals by expecting them to commit

undiscerningly.

Notes

1. Saptapadi are seven steps in Hindu marriage, which begins with invoking the

Gods for plentitude of food, mental and physical strength, a healthy life free

from ailments of couples and attainment of happiness in all walks of life. It

moves on to the fifth step, which is to pray for the welfare of all living entities

in the entire Universe.

2. Gandharva marriages are compared with love marriages to an extent,

because they require only the consent of the partners and take place without

any ceremony, ritual or witness. Existence or ‘God’ is the only witness. For

example, Bhima’s wedding with Hidamba in the Mahabharata.

References

Abraham, L. (2002). Bhai-behen, true love, time pass: Friendships and sexual

partnerships among youth in an Indian metropolis. Culture, Health &

Sexuality, 4(3), 337–353.

Ali, D. (2002). Anxieties of attachment: The dynamics of courtships in medieval

India. Modern Asian Studies, 36(1), 103–139.

Arnett, J.J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late

teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469–480.

———. (2004). Emerging adulthood: The winding road from the late teens

through the twenties. New York: Oxford University Press.

———. (2006). Suffering, selfish, slackers? Myths and reality about emerging

adults. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 36(1), 23–29. doi: 10.1007/

s10964-006-9157-z.

Chopra, P. (2011). Am I an adult: Views of urban Indian youth. Unpublished

doctoral dissertation, The Maharaja Sayajirao University of Baroda, India.

De, S.K. (1959) Ancient Indian erotics and erotic literature. Calcutta: K.L.

Mukhopadhyay.

Delaney, N. (2011). Romantic love and loving commitment: Articulating modern

ideal. American Philosophical Quarterly, 33 (4), 339–356.

Fisher, H.E., Aron, A., & Brown, L.L. (2006). Romantic love: A mammalian

brain system for mate choice. Philosophical Transactions of Royal Society

B, 361, 2173–2186. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1938

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

140 Jigisha Gala and Shagufa Kapadia

Goodwin, W.F. (1955). Ethics and value in Indian philosophy. Philosophy East

and West, 4(4), 321–344. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1396742

(accessed on 17 June, 2010).

Hawley, J.S. (1979). Thief of butter, thief of love. History of Religions, 18(3),

203–220. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1062409 (accessed on

17 June, 2010).

Kapadia, S. (1998, August 3–7). The Indian way: Marriage as the core of human

development. Paper presented at a symposium on Biology and Culture of

Mating for the XIVth Congress of the International Association of Cross-

Cultural Psychology, Bellingham, Washington.

Kapadia, S., Bajpai, D., Roy, S., & Chopra, P. (2007, December). Am I an adult?

Young individuals’ conceptions of adulthood in a contemporary Indian

context. Paper presented at National Conference on Human Development

Research: Commitment to Processes of Change, Department of Human

Development of Home Sceince, Nirmala Niketan, Mumbai.

Kephart, W.M. (1967). Some correlates of romantic love. Journal of Marriage

and the Family, 29, 470–479.

Larson, R., Wilson, S., Brown, B.B., Furstenberg, F.F., & Verma, S. (2002).

Changes in adolescents’ interpersonal experiences: Are they being prepared

for adult relationships in the twenty-first century? Journal of Research on

Adolescence, 12(1), 31–68.

Lefkowitz, E.S., Gillen, M.M., & Vasilenko, S.A. (2011). Putting the romance

back into sex: Sexuality in romantic relationships. In F.D. Fincham & M. Cui

(Eds), Romantic relationships in emerging adulthood (pp. 213–233). NY:

Cambridge University Press.

Mortimer, J.T., & Larson, R.W. (2002). Macrostructural trends and the reshaping

of adolescence. In J.T. Mortimer & R.W. Larson (Eds), The changing

adolescent experience societal trends and the transition to adulthood

(pp. 1–17). UK: Cambridge University Press.

Netting, N. (2010). Marital ideoscapes in 21st-century India: Creative

combinations of love and responsibility. Journal of Family Issues, 31(6),

707–726.

Punja, S. (1992). Divine ecstasy: The story of Khajuraho. New Delhi: Viking.

Seiter, L.N., & Nelson, L. (2011). An examination of emerging adulthood in

college students and nonstudents in India. Journal of Adolescent Research,

26(4), 506–536. doi: 10.1177/0743558410391262.

Siegel, L. (1978). Sacred and profane dimensions of love in Indian Traditions

as exemplified in the Gita Govinda of Jayadeva. London: Oxford University

Press.

Simpson, J.A., Campbell, B., & Berscheid, E. (1986). The association between

romantic love and marriage: Kephart (1967) twice revisited. Personality and

Social Psychology Bulletin, 12, 363–372. doi: 10.1177/0146167286123011.

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

Romantic Love, Commitment and Marriage in Emerging Adulthood 141

Sprecher, S., & Morn, M.T. (2002). A study of men and women from different

sides of earth to determine if men are from mars and women are from venus

in their beliefs about love and romantic relationships. Sex Roles, 46(5/6),

131–147.

Jigisha Gala is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Human

Development and Family Studies, The Faculty of Family and Community

Sciences. Her research interests include adolescent stress and coping

mechanism, life goals and aspirations of emerging adults, gender studies

and risk behaviours amongst adolescents and emerging adults. She is

also interested in giftedness and studies pertaining to values and devel-

opment of ideologies amongst emerging adults.

Shagufa Kapadia is Professor of Human Development and Family

Studies and Director of the Women’s Studies Research Center at the

Faculty of Family and Community Sciences, The Maharaja Sayajirao

University of Baroda, India. Her primary research interest is in unravel-

ling cross-cultural and Indian cultural perspectives on child, adolescent

and youth development and socialisation. She is involved in research on

morality, adolescence and emerging adulthood, immigrant adjustment

and acculturation, reciprocity and social support exchange and gender

issues.

Psychology and Developing Societies, 26, 1 (2014): 115–141

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

142 Editor’s Introduction

Environment and Urbanization Asia, 1, 1 (2010): vii–xii

Downloaded from pds.sagepub.com at M.S. UNIVERSITY OF BARODA on August 2, 2016

View publication stats

You might also like

- Passion, Commitment and Intimacy in Romantic RelationshipsDocument31 pagesPassion, Commitment and Intimacy in Romantic RelationshipsShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Programmable Networks Service Ai ML Operation NewDocument6 pagesProgrammable Networks Service Ai ML Operation NewShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- A Thread From @SwissRamble - #FCBarcelona Are Facing A Financial Crisis, Due To A Combination of Mismanagement and The COVID-19 (... )Document17 pagesA Thread From @SwissRamble - #FCBarcelona Are Facing A Financial Crisis, Due To A Combination of Mismanagement and The COVID-19 (... )Shaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Transforming Contact Centers Into Customer Engagement HubsDocument11 pagesTransforming Contact Centers Into Customer Engagement HubsShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Cloud Security Conference PaperDocument9 pagesCloud Security Conference PaperShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Cultural Perspective On LoveDocument21 pagesCultural Perspective On LovelucasNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Antecedents and Consequences oDocument48 pagesAn Investigation of Antecedents and Consequences oShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Study of Security Risk and Vulnerabilities of Cloud ComputingDocument8 pagesStudy of Security Risk and Vulnerabilities of Cloud ComputingShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Virtual Machine Security Challenges: Case StudiesDocument14 pagesVirtual Machine Security Challenges: Case StudiesShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- WP2016 1-3 3 Study On Security Aspects of Virtualization PDFDocument97 pagesWP2016 1-3 3 Study On Security Aspects of Virtualization PDFDeepthi Suresh100% (1)

- The symbiotic relation of mythical stories in transforming human livesDocument7 pagesThe symbiotic relation of mythical stories in transforming human livesShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Theory of LoveDocument18 pagesTheory of LoveShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Theory of LoveDocument6 pagesTheory of LoveShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Bowlby Attachment TheoryDocument44 pagesBowlby Attachment TheoryYeukTze90% (10)

- The Psychology of Close Relationships: Fourteen Core PrinciplesDocument31 pagesThe Psychology of Close Relationships: Fourteen Core PrinciplesShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Cultural Perspective On LoveDocument21 pagesCultural Perspective On LovelucasNo ratings yet

- Compassionate Love in Romantic Relationships: A Review and Some New FindingsDocument27 pagesCompassionate Love in Romantic Relationships: A Review and Some New FindingsShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Shell script examples to perform various tasksDocument40 pagesShell script examples to perform various tasksShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- French Sem3 PDFDocument44 pagesFrench Sem3 PDFShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Modern Public-Key CryptosystemsDocument57 pagesModern Public-Key CryptosystemsShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Experiment-1 Aim: Write A Program For Implementation of Bit StuffingDocument56 pagesExperiment-1 Aim: Write A Program For Implementation of Bit StuffingShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Presentation On Fiber Distributed Data Interface (FDDI) &Document16 pagesPresentation On Fiber Distributed Data Interface (FDDI) &Shaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Computing With Java Practical File: Master of Computer ApplicationDocument45 pagesEnterprise Computing With Java Practical File: Master of Computer ApplicationShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- SPM Unit 4Document10 pagesSPM Unit 4Shaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Dadu LetterDocument1 pageDadu LetterShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Text Analysis Using Python and Machine Learning Project ReportDocument20 pagesText Analysis Using Python and Machine Learning Project ReportShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Enterprise Computing With Java Practical File: Master of Computer ApplicationDocument45 pagesEnterprise Computing With Java Practical File: Master of Computer ApplicationShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Linux FileDocument33 pagesLinux FileShaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- SPM Unit 1Document18 pagesSPM Unit 1Shaurya KapoorNo ratings yet

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (894)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (399)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (587)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2219)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (119)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Democracy Against Domination PDFDocument257 pagesDemocracy Against Domination PDFvmcosNo ratings yet

- Stone Fox BookletDocument19 pagesStone Fox Bookletapi-220567377100% (3)

- MS For SprinklerDocument78 pagesMS For Sprinklerkarthy ganesanNo ratings yet

- Lighting Design: Azhar Ayyub - Akshay Chaudhary - Shahbaz AfzalDocument27 pagesLighting Design: Azhar Ayyub - Akshay Chaudhary - Shahbaz Afzalshahbaz AfzalNo ratings yet

- BSNL Cda RulesDocument3 pagesBSNL Cda RulesAlexander MccormickNo ratings yet

- Nilai Murni PKN XII Mipa 3Document8 pagesNilai Murni PKN XII Mipa 3ilmi hamdinNo ratings yet

- 11g SQL Fundamentals I Student Guide - Vol IIDocument283 pages11g SQL Fundamentals I Student Guide - Vol IIIjazKhanNo ratings yet

- pmwj93 May2020 Omar Fashina Fakunle Somaliland Construction IndustryDocument18 pagespmwj93 May2020 Omar Fashina Fakunle Somaliland Construction IndustryAdebayo FashinaNo ratings yet