Professional Documents

Culture Documents

E222 Full

Uploaded by

romyOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

E222 Full

Uploaded by

romyCopyright:

Available Formats

Clinical Intelligence

Stephen Spencer, Thajunnisha Buhary, Ian Coulson and Sedki Gayed

Mucosal erosions as the presenting

symptom in erythema multiforme:

a case report

INTRODUCTION DISCUSSION

Erythema multiforme (EM) is an acute and This case demonstrates an interesting

self-limiting hypersensitivity reaction. This scenario in which the initial diagnosis was

article describes the case of a patient who unclear to both GP and secondary care

suffered from a chest infection and later physician, and a range of reasonable

presented with the mucosal manifestations differential diagnoses were made. Mouth

of EM. This condition manifests as skin ulceration secondary to herpes simplex and

lesions, most commonly in reaction to herpes conjunctivitis are both common localised

simplex virus (HSV) 1 and 2, Mycoplasma infections.2,3 SARA presents as a triad of

pneumoniae, or certain medications.1 urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis, or

a pentad including circinate balanitis and

CASE REPORT keratoderma blenorrhagicum.4 Circinate

A 31-year-old male patient presented to his balanitis in this case is an appropriate

GP with cough and fever, sores in his mouth, differential with similar appearances to the

and itchy eyes. He had not received any genital mucosal erosions in EM.

medical attention prior to this appointment, The most common aetiological agents

nor had he taken any recent medications. of EM are HSV 1 and 2, which account

He was initially prescribed aciclovir to treat for >50% of cases. M. pneumoniae is the

oral herpes simplex infection, amoxicillin second most common infective agent

for chest infection, and chloramphenicol for (particularly in children), followed by

conjunctivitis. Two weeks later he was seen fungal infections and other non-herpes

by the medical assessment unit. In addition viral infections. The most associated

to blisters on his mouth and lips (Figure 1), medications with EM are barbiturates, Non-

he developed pruritic blisters on his penis steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs),

and foreskin (Figure 2), small lesions acrally, penicillins, phenothiazines, sulfonamides,

and red eyes. On this basis the consultant and hydantoins. Radiotherapy is another

medical physician referred the patient to known trigger.1

the genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinic to Disease re-classification in 1993 clarified

rule out sexually-acquired reactive arthritis the distinguishing clinical features between

Stephen Spencer, MBChB, FRGS, foundation

year 2 doctor; Thajunnisha Buhary, MD (Sri (SARA) secondary to chlamydia infection. EM, SJS, and toxic epidermal necrolysis

Lanka), DFSRH, DipGUM, specialist registrar The GUM consultant made a provisional (TEN). Although they resemble a disease

in genitourinary medicine; Ian Coulson, FRCP, diagnosis of Stevens–Johnson syndrome spectrum, these diagnoses vary in the pattern

consultant dermatologist, Department of

(SJS) and referred the patient to a of skin lesions and degree of epidermal

Dermatology; Sedki Gayed, FRCOG, FFSRH,

DipGUM, consultant in genitourinary medicine, dermatologist. detachment. These terms are now used in

Department of Genitourinary Medicine, East When reviewed by the dermatologist, the preference over the old terminology: EM

Lancashire Hospitals NHS Trust, Blackburn. patient’s symptoms had improved and he minor and EM major.5

Address for correspondence was able to swallow and drink as normal.

Stephen Spencer, Postgraduate Medical He had no recollection of having cold sores PRESENTATION, DIAGNOSIS, AND

Department, Royal Blackburn Hospital,

Haslingden Road, Blackburn BB2 3HH, UK. or medications prior to the onset of his MANAGEMENT

E-mail: stephenaspencer@doctors.org.uk symptoms. EM is a hypersensitivity reaction. Patients

Submitted: 9 September 2015; Editor’s With this in mind, EM with mucosal present with characteristic ‘target’ rashes

response: 24 September 2015; final involvement secondary to M. pneumoniae with or without mucosal involvement. They

acceptance: 29 September 2015. infection was considered and this was may describe prodromal symptoms and

©British Journal of General Practice later confirmed via the serological particle often complain of itching or burning at the

This is the full-length article (published online agglutination test (>1:640, indicating sites of the lesions.6

26 Feb 2016) of an abridged version published

in print. Cite this article as: Br J Gen Pract ongoing infection). No specific treatment Initial EM lesions appear as polymorphous

2016; DOI: 10.3399/bjgp16X684205 was prescribed, although Vaseline® for his macules that develop into papules and

lips was advised to stop them from sticking. sometimes large plaques. Concentric colour

e222 British Journal of General Practice, March 2016

regions. Epidermal detachment is confined

to <10% of the body surface.

In contrast to EM, SJS has no typical target

lesions, flat atypical targets, and confluent

purpuric macules on the face and trunk

with severe mucosal erosions at one or

more mucosal sites. As with EM, epidermal

detachment is limited to <10% of the body

surface.

TEN is similar to SJS in that there are

no typical targets but flat atypical targets.

However, the disease appears with severe

mucosal erosion and progresses to diffuse

generalised detachment of the epidermis to

>30% of the body surface area.6

Management is directed towards treating

symptoms and removing the cause, and

therefore to treat the suspected infection

or to discontinue the causative medication.5

Furthermore, identifying the aetiology can

provide valuable information regarding

the prognosis. If the trigger is due to

mycoplasma or non-herpes simplex viral

infection, then it is usually a one-off and the

Figure 1. Erosions of the oral mucosa in a case of erythema multiforme. episode will resolve spontaneously within

3–5 weeks without sequelae. However, HSV

is known to cause recurrent EM, which can

be treated with continuous oral aciclovir

(400 mg twice daily).5,7,8 When suppressive

antivirals are not effective, patients should

be referred to dermatology.1

CONCLUSION

This case highlights the need to keep an

open mind that dermatological conditions

can be due to local or systemic processes.

It is important to take a full and thorough

history to identify potential mediators of EM,

and to fully examine the skin to rule out

rashes elsewhere. Although 40% of causes

are idiopathic, there are clear links with

certain infections and medications (as is

the case in this scenario), and these should

be identified for treatment and prognostic

purposes. Not all genital ulcers are related

to genital infections and therefore it is

important to bear in mind systematic and

dermatological diseases that may appear in

the genital region.

Figure 2. Erythema multiforme-associated mucosal erosions of the glans penis.

zones are characteristic of ‘target’ lesions, Patient consent

which vary in morphology (hence the name The patient gave consent for publication of

erythema multiforme). EM is clinically this case report and images.

diagnosed by the presence of these typical

target lesions, as well as raised atypical Provenance

targets, which most often erupt acrally Freely submitted; not externally peer

in EM (as was the case in this patient). reviewed.

Discuss this article Skin biopsies are not necessary unless the Competing interests

Contribute and read comments about diagnosis is unclear. Mucosal erosions may The authors have declared no competing

this article: bjgp.org/letters also be present in oral, genital, or ocular interests.

British Journal of General Practice, March 2016 e223

REFERENCES

1. Lamoreux MR, Sternbach MR, Hsu WT.

Erythema multiforme. Am Fam Physician

2006; 74(11): 1883–1888.

2. Høvding G. Acute bacterial conjunctivitis. Acta

Ophthalmol 2008; 86(1): 5–17.

3. Looker KJ, Garnett GP. A systematic review

of the epidemiology and interaction of herpes

simplex virus types 1 and 2. Sex Transm Infect

2005; 81(2): 103−107.

4. Kanwar AJ, Mahajan R. Reactive arthritis in

India: a dermatologist’s perspective. J Cutan

Med Surg 2013; 17(3): 180–188.

5. Bastuji-Garin S, Rzany B, Stern RS, et

al. Clinical classification of cases of toxic

epidermal necrolysis, Stevens–Johnson

syndrome, and erythema multiforme. Arch

Dermatol 1993; 129(1): 92–96.

6. Sokumbi O, Wetter DA. Clinical features,

diagnosis, and treatment of erythema

multiforme: a review for the practicing

dermatologist. Int J Dermatol 2012; 51(8):

889–902.

7. Weston WL. Herpes-associated erythema

multiforme. J Invest Dermatol 2005; 124(6):

15–16.

8. Osterne RL, de Matos Brito RG, Pacheco IA,

et al. Management of erythema multiforme

associated with recurrent herpes infection:

a case report. J Can Dent Assoc 2009; 75(8):

597–601.

e224 British Journal of General Practice, March 2016

You might also like

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A ReviewDocument6 pagesStevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A ReviewDede Rahman AgustianNo ratings yet

- Stevens-Johnson SyndromeDocument4 pagesStevens-Johnson SyndromeBelleNo ratings yet

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A ReviewDocument6 pagesStevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: A Reviewイアン リムホト ザナガNo ratings yet

- 303 1644 1 PB PDFDocument5 pages303 1644 1 PB PDFMahesa Diantari100% (1)

- Em IvDocument4 pagesEm IvathiyafrNo ratings yet

- Erythema Multiforme Major: Case Report and Review of LiteratureDocument6 pagesErythema Multiforme Major: Case Report and Review of LiteratureSasa AprilaNo ratings yet

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis - ClinicalKeyDocument21 pagesStevens-Johnson Syndrome and Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis - ClinicalKeyMasithaNo ratings yet

- Ijccm 25 575Document5 pagesIjccm 25 575Nandha KumarNo ratings yet

- Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Erythema Multiforme: A Review For The Practicing DermatologistDocument14 pagesClinical Features, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Erythema Multiforme: A Review For The Practicing DermatologistBiljana CavdarovskaNo ratings yet

- Print Jurnal 3Document7 pagesPrint Jurnal 3Amalia GrahaniNo ratings yet

- Putra,+18 Bmj.v5i1.274Document9 pagesPutra,+18 Bmj.v5i1.274noor hidayahNo ratings yet

- Jurnal KulitDocument8 pagesJurnal Kulitzak bearNo ratings yet

- Clinical Features, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Erythema Multiforme - A Review For The Practicing DermatologistDocument14 pagesClinical Features, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Erythema Multiforme - A Review For The Practicing Dermatologist2211801733No ratings yet

- Drug Induced-Stevens Johnson Syndrome: A Case ReportDocument26 pagesDrug Induced-Stevens Johnson Syndrome: A Case ReportdoktersandraNo ratings yet

- Acute Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis: Ravi Prakash Sasankoti Mohan, Sankalp Verma, Udita Singh, Neha AgarwalDocument3 pagesAcute Primary Herpetic Gingivostomatitis: Ravi Prakash Sasankoti Mohan, Sankalp Verma, Udita Singh, Neha AgarwalBrili AnenoNo ratings yet

- "Drug Induced Erythema Multiforme" - A ReviewDocument7 pages"Drug Induced Erythema Multiforme" - A ReviewNauroh NaurohNo ratings yet

- Successful Treatment of Herpes Simplex-Associated Erythema Multiforme With A Combination of Acyclovir and PrednisoneDocument3 pagesSuccessful Treatment of Herpes Simplex-Associated Erythema Multiforme With A Combination of Acyclovir and PrednisoneannisafebriezaNo ratings yet

- Bieber, T.Document7 pagesBieber, T.Anak Agung Ayu Ira Kharisma Buana Undiksha 2019No ratings yet

- Pharmacological Management of Common Soft Tissue Lesions of The Oral CavityDocument16 pagesPharmacological Management of Common Soft Tissue Lesions of The Oral CavityAcisum2No ratings yet

- Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis of The Mandible: Report of Three CasesDocument12 pagesChronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis of The Mandible: Report of Three CasesandrikaNo ratings yet

- Case Report 2 PDFDocument5 pagesCase Report 2 PDFSittiNurQomariahNo ratings yet

- Stevens-Johnson Syndrome and Abuse of Anabolic SteroidsDocument4 pagesStevens-Johnson Syndrome and Abuse of Anabolic SteroidsRafael SebastianNo ratings yet

- Nicotine-Induced Bullous Fixed Drug EruptionDocument3 pagesNicotine-Induced Bullous Fixed Drug Eruptionamal amanahNo ratings yet

- Paracetamol Induced Steven-Johnson Syndrome A Rare Case ReportDocument4 pagesParacetamol Induced Steven-Johnson Syndrome A Rare Case ReporthadiatussalamahNo ratings yet

- HFMD Immunocompeten AdultDocument3 pagesHFMD Immunocompeten AdultdantiNo ratings yet

- Case Study On Pemphigus VulgarisDocument2 pagesCase Study On Pemphigus VulgarisRanindya PutriNo ratings yet

- 571 FullDocument2 pages571 FullJauhari JoNo ratings yet

- Case Report Benign Mucosal Membrane Pemphigoid As A Differential Diagnosis of Necrotizing Periodontal DiseaseDocument4 pagesCase Report Benign Mucosal Membrane Pemphigoid As A Differential Diagnosis of Necrotizing Periodontal DiseaseYeni PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Drug-Mediated Rash: Erythema Multiforme Versus Stevens-Johnson SyndromeDocument4 pagesDrug-Mediated Rash: Erythema Multiforme Versus Stevens-Johnson SyndromeMădălina ŞerbanNo ratings yet

- 8 Bains A (49-52) PDFDocument4 pages8 Bains A (49-52) PDFWa JulianiNo ratings yet

- 7692-Article Text-30295-3-10-20200319 PDFDocument4 pages7692-Article Text-30295-3-10-20200319 PDFHata BotonjicNo ratings yet

- Pemphigus Vulgaris 1Document3 pagesPemphigus Vulgaris 1Yeni PuspitasariNo ratings yet

- Primary Conjunctival Tuberculosis-2Document3 pagesPrimary Conjunctival Tuberculosis-2puutieNo ratings yet

- PDM Os4Document3 pagesPDM Os4Erdinawira RizkianiNo ratings yet

- Stevens Johnson SyndromeDocument9 pagesStevens Johnson SyndromeMrslidyaNo ratings yet

- Chronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis of The Mandible: Report of Three CasesDocument12 pagesChronic Recurrent Multifocal Osteomyelitis of The Mandible: Report of Three CasesandrikaNo ratings yet

- Erythema MultiformeDocument16 pagesErythema MultiformeGuen ColisNo ratings yet

- Recent Updates in the Treatment of Erythema MultiformeDocument8 pagesRecent Updates in the Treatment of Erythema MultiformeimantikachristinaaaNo ratings yet

- SJSInJPharPract 12 2 133 PDFDocument3 pagesSJSInJPharPract 12 2 133 PDFRidho Nugroho Wahyu AkbarNo ratings yet

- Herpetic) : Titis Virus13Document10 pagesHerpetic) : Titis Virus13John Michael VicenteNo ratings yet

- ClinRevSJsyndrome PDFDocument5 pagesClinRevSJsyndrome PDFMuhammad Nur Ardhi LahabuNo ratings yet

- Erythema Multiforme: A Case Series and Review of Literature: November 2018Document8 pagesErythema Multiforme: A Case Series and Review of Literature: November 2018Nurlina NurdinNo ratings yet

- PV 1Document4 pagesPV 1Aing ScribdNo ratings yet

- Erythema Multiforme-Oral Variant: Case Report and Review of LiteratureDocument4 pagesErythema Multiforme-Oral Variant: Case Report and Review of LiteratureMarniati JohanNo ratings yet

- BullousDocument3 pagesBullousLjubomirErdoglijaNo ratings yet

- Tugas BacaDocument20 pagesTugas BacaAyu WulansariNo ratings yet

- Autoinflammatory Syndromes Associated With Hidradenitis Suppurativa and or AcneDocument8 pagesAutoinflammatory Syndromes Associated With Hidradenitis Suppurativa and or AcneFreddy RojasNo ratings yet

- Mockenhaupt Eemm Sjs TenDocument6 pagesMockenhaupt Eemm Sjs TengratianusbNo ratings yet

- Recurrent Erythema Multiforme: A Dental Case Report: ReviewDocument4 pagesRecurrent Erythema Multiforme: A Dental Case Report: Reviewjenn_1228No ratings yet

- Epidermodysplasia Verruciformis Tree Man Syndrome A Brief Review With Case Reports 177Document3 pagesEpidermodysplasia Verruciformis Tree Man Syndrome A Brief Review With Case Reports 177Medtext PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Herpes Zoster: A Case ReportDocument3 pagesHerpes Zoster: A Case ReportAhmad HaikalNo ratings yet

- Jawt 11 I 2 P 48Document3 pagesJawt 11 I 2 P 48Irma NoviantiNo ratings yet

- Journal Rosacea Report Lain PDFDocument5 pagesJournal Rosacea Report Lain PDFtesaNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 0190962214011566Document2 pagesPi Is 0190962214011566LewishoppusNo ratings yet

- Cheilitis Granulomatosa of Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome: Treatment With Intralesional Corticosteroid InjectionsDocument3 pagesCheilitis Granulomatosa of Melkersson-Rosenthal Syndrome: Treatment With Intralesional Corticosteroid InjectionsTatiana OrdoñezNo ratings yet

- 2 em 1Document1 page2 em 1Érica MarianoNo ratings yet

- Herpes Zoster Oticus in A 12 Year Old Child and Review of Literature - A CaseDocument5 pagesHerpes Zoster Oticus in A 12 Year Old Child and Review of Literature - A CaseClodeyaRizolaNo ratings yet

- Rash and Fever After Sulfasalazine UseDocument5 pagesRash and Fever After Sulfasalazine UseChistian LassoNo ratings yet

- Obstetrics 4 1084Document2 pagesObstetrics 4 1084Irma NoviantiNo ratings yet

- Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsFrom EverandToxic Epidermal Necrolysis, A Simple Guide To The Condition, Diagnosis, Treatment And Related ConditionsNo ratings yet

- 1a - 607 Acc - Research Article - LNDocument5 pages1a - 607 Acc - Research Article - LNromyNo ratings yet

- Neurofibromatosis Type 2: Review ArticlesDocument9 pagesNeurofibromatosis Type 2: Review ArticlesPaviliuc RalucaNo ratings yet

- Oral Manifestations of Gardner's Syndrome in Young Patients: Report of Three CasesDocument5 pagesOral Manifestations of Gardner's Syndrome in Young Patients: Report of Three Casesromy100% (1)

- 4 Determinants of Family Independence in Caring For Hebephrenic Schizophrenia Patients-MinDocument9 pages4 Determinants of Family Independence in Caring For Hebephrenic Schizophrenia Patients-MinromyNo ratings yet

- Cirrhotic Ascites: A Review of Pathophysiology and ManagementDocument10 pagesCirrhotic Ascites: A Review of Pathophysiology and ManagementromyNo ratings yet

- 1608 04192 PDFDocument13 pages1608 04192 PDFromyNo ratings yet

- Neurofibromatosis Type 1: ClinicalpictureDocument1 pageNeurofibromatosis Type 1: ClinicalpictureromyNo ratings yet

- BPJ Vol 11 No 1 P 167-170Document4 pagesBPJ Vol 11 No 1 P 167-170indrayaniNo ratings yet

- Hepatic Encephalopathy: Peter FerenciDocument10 pagesHepatic Encephalopathy: Peter FerenciromyNo ratings yet

- PIIS0953620519303413Document7 pagesPIIS0953620519303413romyNo ratings yet

- Pharmaceuticals: Critical Overview On The Benefits and Harms of AspirinDocument16 pagesPharmaceuticals: Critical Overview On The Benefits and Harms of AspirinromyNo ratings yet

- Imj 13735Document6 pagesImj 13735romyNo ratings yet

- Dentistry: Gardener Syndrome: A Rare Case ReportDocument3 pagesDentistry: Gardener Syndrome: A Rare Case ReportromyNo ratings yet

- v09p0137 PDFDocument5 pagesv09p0137 PDFromyNo ratings yet

- Walking Is More Efficient Than Thought For Threatened Polar BearsDocument1 pageWalking Is More Efficient Than Thought For Threatened Polar BearsromyNo ratings yet

- Gingivitis A Silent Disease PDFDocument4 pagesGingivitis A Silent Disease PDFPragita Ayu SaputriNo ratings yet

- The Diagnosis and Management of Atypical Types of Diabetes: Kathryn Evans Kreider, DNP, FNP-BCDocument7 pagesThe Diagnosis and Management of Atypical Types of Diabetes: Kathryn Evans Kreider, DNP, FNP-BCromyNo ratings yet

- Bird predation by praying mantisesDocument14 pagesBird predation by praying mantisesromyNo ratings yet

- Fulminant Hepatitis: Definitions, Causes and Management: Vincenzo Morabito, Danielle AdebayoDocument11 pagesFulminant Hepatitis: Definitions, Causes and Management: Vincenzo Morabito, Danielle AdebayoIvan Yoseph SaputraNo ratings yet

- Concise Clinical Review: Anthrax InfectionDocument9 pagesConcise Clinical Review: Anthrax Infectionaulia rahadianNo ratings yet

- QUT Digital Repository: 29984Document15 pagesQUT Digital Repository: 29984romyNo ratings yet

- 2017-Colibri MAVDocument14 pages2017-Colibri MAVromyNo ratings yet

- Why and How We Are Not ZombiesDocument4 pagesWhy and How We Are Not ZombiesromyNo ratings yet

- Anticipating The Zombie Apocalypse Using ImprobabiDocument13 pagesAnticipating The Zombie Apocalypse Using ImprobabiromyNo ratings yet

- Zombie PublicationDocument20 pagesZombie PublicationJordan MoshcovitisNo ratings yet

- Seizures in COVID 19Document2 pagesSeizures in COVID 19romyNo ratings yet

- The Magical Power of Blood: The Curse of The Vampire From An Anthropological Point of WievDocument35 pagesThe Magical Power of Blood: The Curse of The Vampire From An Anthropological Point of WievromyNo ratings yet

- COVID19-and-Epilepsy FAQ 040920 v3Document4 pagesCOVID19-and-Epilepsy FAQ 040920 v3romyNo ratings yet

- Integrated Pest Management of The German Cockroach (Blattodea: Blattellidae) in Manufactured Homes in Rural North CarolinaDocument7 pagesIntegrated Pest Management of The German Cockroach (Blattodea: Blattellidae) in Manufactured Homes in Rural North CarolinaromyNo ratings yet

- Internal Medicine (I) Log Book Black Color TypingDocument48 pagesInternal Medicine (I) Log Book Black Color TypingQasim HaleimiNo ratings yet

- Megaloblastic Anemia PPTDocument2 pagesMegaloblastic Anemia PPTmoncalshareen3No ratings yet

- Aspek Medis Bedah (Perioperatif) Dan Enteral - Parenteral NutrisiDocument56 pagesAspek Medis Bedah (Perioperatif) Dan Enteral - Parenteral NutrisiJashmine RachlyNo ratings yet

- Week 7. Renal Pathology Continued.Document9 pagesWeek 7. Renal Pathology Continued.Amber LeJeuneNo ratings yet

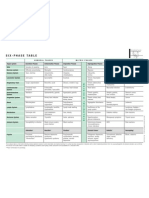

- Six-Phase Table: International Society of HomotoxicologyDocument1 pageSix-Phase Table: International Society of HomotoxicologyPablo Matas SoriaNo ratings yet

- Drug Study (Loxapine, Haloperidol)Document5 pagesDrug Study (Loxapine, Haloperidol)kuro hanabusa100% (2)

- 4 6030444038488853198 PDFDocument110 pages4 6030444038488853198 PDFSyeda Seri RazaNo ratings yet

- Gestational Choriocarcinoma OranuDocument8 pagesGestational Choriocarcinoma Oranuapi-3705046No ratings yet

- Recognition and Interpretation of Skin 1Document6 pagesRecognition and Interpretation of Skin 1Veterinarios de ArgentinaNo ratings yet

- SSM-11th Edn Full IndexDocument62 pagesSSM-11th Edn Full Indexece142No ratings yet

- Controlling asthma with AlbuterolDocument2 pagesControlling asthma with AlbuterolVinz Khyl G. CastillonNo ratings yet

- Koding Icd 10 & Icd 9 NewwDocument30 pagesKoding Icd 10 & Icd 9 NewwJar Jar79% (14)

- Musculoskeletal RadiologyDocument5 pagesMusculoskeletal Radiologyapi-3743483No ratings yet

- Pocket Book of Hospital Care For Children - Guidleines For The Management of Common Illnesses With Limited Resources. (2012, World Health Organization)Document442 pagesPocket Book of Hospital Care For Children - Guidleines For The Management of Common Illnesses With Limited Resources. (2012, World Health Organization)Sadia YousafNo ratings yet

- Eyelid Disorders Guide: Ptosis, Blepharitis, Hordeolum & MoreDocument48 pagesEyelid Disorders Guide: Ptosis, Blepharitis, Hordeolum & MoreUdaif BabuNo ratings yet

- Drug StudyDocument3 pagesDrug StudySoniaMarieBalanayNo ratings yet

- Fitzpatricks Dermatology 9th Edition 3123Document1 pageFitzpatricks Dermatology 9th Edition 3123DennisSujayaNo ratings yet

- Ileus Obstruksi - Anggi Eka ForendaDocument12 pagesIleus Obstruksi - Anggi Eka ForendaNadya ZahraNo ratings yet

- Biomo306 Quiz One QuestionsDocument5 pagesBiomo306 Quiz One QuestionsAdrianNo ratings yet

- BOTOXDocument12 pagesBOTOXJanani KrishnanNo ratings yet

- Drugs Acting On The AnsDocument57 pagesDrugs Acting On The AnsAnonymous iG0DCOfNo ratings yet

- Treatment For Subdural HygromaDocument3 pagesTreatment For Subdural HygromaEka NataNo ratings yet

- Fish Diseases (Jorge C. Eiras, Helmut Segner, Thomas Wahli Etc.) (Z-Library)Document1,327 pagesFish Diseases (Jorge C. Eiras, Helmut Segner, Thomas Wahli Etc.) (Z-Library)Iryna ZapekaNo ratings yet

- Red Man SyndromeDocument3 pagesRed Man Syndrome林唐宇No ratings yet

- PTH 725 - Multiple-Sclerosis-Case StudyDocument19 pagesPTH 725 - Multiple-Sclerosis-Case StudyEnrique Guillen InfanteNo ratings yet

- Q&A Pharmacology 2Document19 pagesQ&A Pharmacology 2api-3818438No ratings yet

- Common Lab Tests & Their Use in Diagnosis & Treatment PDFDocument17 pagesCommon Lab Tests & Their Use in Diagnosis & Treatment PDFChAwaisNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Amalgam TatoDocument2 pagesJurnal Amalgam TatoLu'luatul WidadNo ratings yet

- Curs VII - Terapii SistemiceDocument229 pagesCurs VII - Terapii SistemiceHucay EduardNo ratings yet

- 2 PDFDocument297 pages2 PDFTaj KoyyodeNo ratings yet