Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Confrence

Uploaded by

Amartya ChoubeyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Confrence

Uploaded by

Amartya ChoubeyCopyright:

Available Formats

Placating tribals

On November 15, 2000, tribals, mostly from central India, had something to rejoice about. A demand

articulated for over a century saw the birth of the state of Jharkhand.

Demands for separate statehood for Jharkhand were first raised in 1914 by tribals, as mentioned in the

State Reorganisation Committee Report 1955-56. Tribal politicians vigorously took up the cause,

supported by other indigenous communities. For long, the mineral-rich areas of Chota Nagpur and

Santhal Pargana had been exploited and the tribal people displaced in the name of development.

Racial discrimination of tribals by outsiders, referred to as dikus in the tribal tongue, was rampant. The

demand for separate statehood was not merely to establish a distinct identity but also to do away with years

of injustice.

However, the creation of Jharkhand has only increased the vulnerability of tribals. The token concessions

of a tribal chief minister and a few reserved constituencies were deemed a green signal to displace tribals

for so-called ‘development’. According to reports of the Indian People’s Tribunal on Environment and

Human Rights, a total of 6.54 million people have so far been displaced in Jharkhand in the name of

development. The ongoing land acquisition at Nagri village (near Ranchi, Jharkhand) for the Indian

Institute of Management (IIM) and National University of Study and Research in Law (NUSRL) may seem

like development projects in the eyes of the educated and the affluent. But these elite educational institutes

have displaced over 500 tribal villagers. The displacement in the name of dams, factories, mining, etc goes

largely unreported.

In a place where displacement and development have become synonymous, the strategic reasons for such

oppressive measures go beyond monetary gain. One senses, quite palpably, consistent attempts by various

corporate firms to exert control over the policy formulation process. This political-corporate nexus was

very apparent when 42 MoUs were signed as soon as Jharkhand came into being. According to a

human rights report published by the Jharkhand Human Rights Movement (JHRM), the state

government of Jharkhand has so far signed 102 MoUs which go against the laws of the Fifth

Schedule. Vast tracts of land will be required to bring these MoUs to fruition.

People’s opposition and various constitutional laws against land acquisition have always been

impediments to the corporations. In 2011, a people’s movement forced Arcelor Mittal to pull out of a

proposed project in Jharkhand. The corporate sector has been trying hard to change the status quo in its

favour, and in doing so has adopted some dubious means. The Chota Nagpur Tenancy (CNT) Act is one

of several laws provided by the Constitution to safeguard tribal interests. It was instituted in 1908 to

safeguard tribal lands from being sold to non-tribals. The law was meant to prevent foreseeable

dispossession, and preserve tribal identity. Loss of land would naturally lead to loss of tribal identity as the

issuance of a community certificate requires proof of land possession.

The private sector seems to have taken a special interest in drastically reforming or abolishing the CNT

Act. Corporate-owned newspapers like Prabhat Khabar and Dainik Bhaskar have campaigned vigorously

for reforming the Act to make transfer of land from tribals to non-tribals more flexible. Needless to say,

any reform in this direction would directly benefit corporations that own mines in the tribal lands of

Jharkhand, and pave the way for future land acquisition.

The state government, irrespective of party banner, has been part of such threats to tribal interests. Non-

inclusion of the Sarna religion in the religion category of census data has drastically downsized tribal

populations. There have been lapses on the part of the administration to provide accurate data on tribal

populations, many of which are underreported.

With the never-ending displacement, the tribal population figure has dropped to a mere 28% on paper.

You might also like

- Media, Conflict and Peace in Northeast IndiaFrom EverandMedia, Conflict and Peace in Northeast IndiaDr. KH KabiNo ratings yet

- Jal, Jangal Aur Jameen - ' The Pathalgadi Movement and Adivasi Rights PDFDocument5 pagesJal, Jangal Aur Jameen - ' The Pathalgadi Movement and Adivasi Rights PDFDiXit JainNo ratings yet

- Acquition of Land in Tribal Areas - CGLRCDocument21 pagesAcquition of Land in Tribal Areas - CGLRCSameer Saurabh100% (1)

- Strengthening Partnership Between States and Indigenous Peoples - Treaties, Agreements and Other Constructive Arrangements - DDG DympepDocument6 pagesStrengthening Partnership Between States and Indigenous Peoples - Treaties, Agreements and Other Constructive Arrangements - DDG DympepLamshwa KitbokNo ratings yet

- History of Jharkhand MovementDocument4 pagesHistory of Jharkhand MovementbibinNo ratings yet

- Pathalgadi Movement in Jharkhand Withdrawal of CasesDocument4 pagesPathalgadi Movement in Jharkhand Withdrawal of CasesarbitrunningNo ratings yet

- Does Raising Questions On The Rights of Adivasis Make Me A Deshdrohi'?Document6 pagesDoes Raising Questions On The Rights of Adivasis Make Me A Deshdrohi'?Abhishek SukenkarNo ratings yet

- SPS Insight Analysis of Chittagong HillDocument9 pagesSPS Insight Analysis of Chittagong Hillnew backupNo ratings yet

- The Gorkhaland MovementDocument30 pagesThe Gorkhaland MovementAniket ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Land Alination in JharkhandDocument5 pagesLand Alination in JharkhandTHERALI KIKONNo ratings yet

- Why The Emergence of New StatesDocument4 pagesWhy The Emergence of New Statessaarika_saini1017No ratings yet

- 24 April Observed Round The CountryDocument12 pages24 April Observed Round The CountryDrBabu PSNo ratings yet

- Ethnic Conflict in A Post Accord SituatiDocument14 pagesEthnic Conflict in A Post Accord SituatiLearn BDNo ratings yet

- TribalDocument3 pagesTribalRakshit GuptaNo ratings yet

- Tribal Land Alienation in Andhra PradeshDocument7 pagesTribal Land Alienation in Andhra PradeshHarsha VytlaNo ratings yet

- Definition of Indigenous PeoplesDocument19 pagesDefinition of Indigenous PeoplesJeysan MahmudNo ratings yet

- Why GorkhalandDocument22 pagesWhy GorkhalandAnupam Gurung100% (2)

- Land Alienation Report 2009Document7 pagesLand Alienation Report 2009monikaxingNo ratings yet

- STAT ConDocument20 pagesSTAT ConThea Mae Morgia WacasNo ratings yet

- Avinash Kumar (Status of Tribal Communities in Post-Independence India)Document7 pagesAvinash Kumar (Status of Tribal Communities in Post-Independence India)Avinash KumarNo ratings yet

- APPWW Opposition To St. Paul ResolutionDocument3 pagesAPPWW Opposition To St. Paul ResolutionPGurusNo ratings yet

- Ijmra 15107Document9 pagesIjmra 15107sanjog DewanNo ratings yet

- VIEWS ''Pathalgadi'': Tribal Assertion For Self-Rule: July 2018Document6 pagesVIEWS ''Pathalgadi'': Tribal Assertion For Self-Rule: July 2018Arghadeep BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Chennai SpeechDocument12 pagesChennai SpeechBinayakSenNo ratings yet

- Book On Schedules Tribes - Governance in The Scheduled AreasDocument164 pagesBook On Schedules Tribes - Governance in The Scheduled AreasSoitda BcmNo ratings yet

- State Reorganisation-1Document15 pagesState Reorganisation-1Hrilthangmawi PakhuongteNo ratings yet

- Tribal Extreism MoistDocument29 pagesTribal Extreism Moistdevdd28No ratings yet

- 1771-Article Text-3392-1-10-20180203Document13 pages1771-Article Text-3392-1-10-20180203Amartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Task 2 Internship (The Status of Refugee in India)Document7 pagesTask 2 Internship (The Status of Refugee in India)Nikchen TamangNo ratings yet

- Law and PovertyDocument24 pagesLaw and PovertySai VijitendraNo ratings yet

- 8th Annual SRMNMCC 2023 - MOOT PROPOSITIONDocument4 pages8th Annual SRMNMCC 2023 - MOOT PROPOSITIONMohammed ShakeelNo ratings yet

- Citizenship Amendment Act CAA 2019 in India The Conflict Between Humanity and Cultural IdentityDocument3 pagesCitizenship Amendment Act CAA 2019 in India The Conflict Between Humanity and Cultural IdentityEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Regional IsmDocument16 pagesRegional IsmKamlesh PatelNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Violations by Multinational Corporations - Precautionary and Remedial MeasuresDocument8 pagesHuman Rights Violations by Multinational Corporations - Precautionary and Remedial MeasuresNiranjan M S RighthereNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Scheduled TribesDocument4 pagesDissertation Scheduled TribesOrderAPaperBillings100% (1)

- Sept 2021Document82 pagesSept 2021Rudra ChinmayeeNo ratings yet

- Politics of Reorganization of States Needs Complete RevaluationDocument7 pagesPolitics of Reorganization of States Needs Complete RevaluationPraveen SaiNo ratings yet

- Khas Land A Study On Existing Law and PracticeDocument13 pagesKhas Land A Study On Existing Law and PracticeparvezNo ratings yet

- Hat Is Athalgadi OvementDocument21 pagesHat Is Athalgadi OvementABHINAV DEWALIYANo ratings yet

- Directed The Central GovernmentDocument9 pagesDirected The Central GovernmentMayank SenNo ratings yet

- 87 May 2020 - 2Document13 pages87 May 2020 - 2Purushothaman ANo ratings yet

- Unit 19 Elwin and Ghuryes Perspectives On Tribes PDFDocument18 pagesUnit 19 Elwin and Ghuryes Perspectives On Tribes PDFRohitNo ratings yet

- Democratise The Development Process in Odisha - How Many Ions of DevelopmentDocument3 pagesDemocratise The Development Process in Odisha - How Many Ions of DevelopmentPravin PatelNo ratings yet

- Chhotanagpur Tenancy Act 1908Document4 pagesChhotanagpur Tenancy Act 1908Navotna ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Lok Sabha - Dealing With The Issue of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons in The CountryDocument14 pagesLok Sabha - Dealing With The Issue of Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons in The Countryjohaanjacob45No ratings yet

- Human Rights ReportDocument90 pagesHuman Rights ReportHarry SiviaNo ratings yet

- Sub: E.H.S Topic: A Study On The Struggle of GorkhalandDocument16 pagesSub: E.H.S Topic: A Study On The Struggle of Gorkhalandsanjog DewanNo ratings yet

- A Separate TelanganaDocument5 pagesA Separate TelanganaParth PatelNo ratings yet

- Persons in NewsDocument8 pagesPersons in NewsSachin DhariwalNo ratings yet

- Politics of Tribal Land RightsDocument4 pagesPolitics of Tribal Land RightsdevitulasiNo ratings yet

- India (Citizenship Amendment Act)Document13 pagesIndia (Citizenship Amendment Act)Mudit GoelNo ratings yet

- CaseStudy 06 India JharkhandDocument54 pagesCaseStudy 06 India JharkhandJaykishan Godsora0% (1)

- 13 Chapter 6Document28 pages13 Chapter 6Mriganka BoraNo ratings yet

- IR Second Term PaperDocument10 pagesIR Second Term PaperUjwal NiraulaNo ratings yet

- Rs. 20 Lakh Crore Haryana Realestate ScamDocument53 pagesRs. 20 Lakh Crore Haryana Realestate ScamSrini KalyanaramanNo ratings yet

- Myanmar's Democratic Transition: Peril or Promise For The Stateless Rohingya?Document15 pagesMyanmar's Democratic Transition: Peril or Promise For The Stateless Rohingya?Arafat jamilNo ratings yet

- The Chhattisgarh Community Forest Rights Project, IndiaDocument10 pagesThe Chhattisgarh Community Forest Rights Project, IndiaOxfamNo ratings yet

- Xaxa Committee On Tribal Communities of India: Schedule TribesDocument27 pagesXaxa Committee On Tribal Communities of India: Schedule TribesTejas AthawaleNo ratings yet

- Moot Proposition - Aimcc 2022Document8 pagesMoot Proposition - Aimcc 2022Anurag DwivediNo ratings yet

- Final Research Paper of Contract @amandeepDocument11 pagesFinal Research Paper of Contract @amandeepAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- ADM LAw in 21 Century PDFDocument24 pagesADM LAw in 21 Century PDFAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- State LegislatureDocument15 pagesState LegislatureAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Parliament of IndiaDocument96 pagesParliament of IndiaAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- ELECTIONSDocument30 pagesELECTIONSAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Chotanagpur Tenancy Act PDFDocument276 pagesChotanagpur Tenancy Act PDFRohan Vijay100% (1)

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument9 pagesScanned With CamscannerAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Delegated LegistationDocument27 pagesDelegated LegistationAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Adminstrative Law NotesDocument13 pagesAdminstrative Law NotesAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Services Under The Union and The States andDocument23 pagesServices Under The Union and The States andAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Historical Background of Administrative Law - The Inquest ProcedurDocument19 pagesHistorical Background of Administrative Law - The Inquest ProcedurAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Services Under The Union and The States andDocument23 pagesServices Under The Union and The States andAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Indian Penal CodeDocument2 pagesIndian Penal CodeAMIT GUPTANo ratings yet

- Official LanguageDocument15 pagesOfficial LanguageAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- High CourtsDocument50 pagesHigh CourtsAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Public Service CommissionDocument17 pagesPublic Service CommissionAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Supreme CourtDocument70 pagesSupreme CourtAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Union ExecutiveDocument66 pagesUnion ExecutiveAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Expansion of Adm LawDocument20 pagesExpansion of Adm LawAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Parliamentary Privileges PDFDocument31 pagesParliamentary Privileges PDFAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Article 370Document11 pagesArticle 370Amartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Financial RelationsDocument81 pagesFinancial RelationsAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Jurisdiction and Powers of The Supreme CourtDocument143 pagesJurisdiction and Powers of The Supreme CourtAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- ELECTIONSDocument30 pagesELECTIONSAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- The American Model of Federal Administrative Law - Remembering TheDocument19 pagesThe American Model of Federal Administrative Law - Remembering TheAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Dai-Ichi Karkaria Private LTD., Bombay vs. Oil and Natural GasDocument36 pagesDai-Ichi Karkaria Private LTD., Bombay vs. Oil and Natural GasAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Separation of Power in Theory N PracticeDocument36 pagesSeparation of Power in Theory N PracticeAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Historical Background of Administrative Law - The Inquest ProcedurDocument19 pagesHistorical Background of Administrative Law - The Inquest ProcedurAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- National University of Study and Research in Law: RanchiDocument12 pagesNational University of Study and Research in Law: RanchiAmartya ChoubeyNo ratings yet

- Chotanagpur Tenancy Act PDFDocument276 pagesChotanagpur Tenancy Act PDFRohan Vijay100% (1)

- Result Cls10 11023 2020Document48 pagesResult Cls10 11023 2020Vikash KumarNo ratings yet

- Sl. No. Sap Id Name Date of BirthDocument19 pagesSl. No. Sap Id Name Date of BirthManish RajNo ratings yet

- BastacollaDocument205 pagesBastacollaAbhijeetNo ratings yet

- CV Format For QSDocument4 pagesCV Format For QSAbhinav KumarNo ratings yet

- Art Integrated ProjectDocument15 pagesArt Integrated Projectashutoshkumar1953No ratings yet

- Birsa MundaDocument10 pagesBirsa MundaSuReShNo ratings yet

- Sem VIII - A PDFDocument13 pagesSem VIII - A PDFRam Kumar YadavNo ratings yet

- Momentum Jharkhand PoliciesDocument33 pagesMomentum Jharkhand PoliciesMousumi PaulNo ratings yet

- Faculty Profile of Kolhan University, Chaibasa Title: Whatsapp: 9031347466Document7 pagesFaculty Profile of Kolhan University, Chaibasa Title: Whatsapp: 9031347466chandra DiveshNo ratings yet

- IOCLLocationDocument24 pagesIOCLLocationAadrita RoyNo ratings yet

- JharkhandDocument5 pagesJharkhandVARSHA0% (1)

- Case 4 Amadubi Rural Tourism Project ADocument14 pagesCase 4 Amadubi Rural Tourism Project ADani YustiardiNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology: The Overall Impact On Rural HouseholdsDocument2 pagesResearch Methodology: The Overall Impact On Rural HouseholdsRobin GhotiaNo ratings yet

- All Complaints Forwarded Through Email Should Contain Contact Number & Complete Postal Address of The ComplainantDocument3 pagesAll Complaints Forwarded Through Email Should Contain Contact Number & Complete Postal Address of The ComplainantReeta DuttaNo ratings yet

- Concepts of Manufacturing RegionDocument20 pagesConcepts of Manufacturing RegionThanpuia JongteNo ratings yet

- Sem. IIDocument12 pagesSem. IIKrishan RawatNo ratings yet

- Santhal Rebellion: Submitted By-Sajal Sanatan, B.A.Ll.B. Submitted To - Dr. Priyadarshini Sajal Sanatan (2149)Document6 pagesSanthal Rebellion: Submitted By-Sajal Sanatan, B.A.Ll.B. Submitted To - Dr. Priyadarshini Sajal Sanatan (2149)sajal sanatanNo ratings yet

- PG Semester IDocument15 pagesPG Semester IRam YadavNo ratings yet

- Rodata Jharkhand PDFDocument5 pagesRodata Jharkhand PDFshivam raiNo ratings yet

- District Mineral Foundation DMF ReportDocument56 pagesDistrict Mineral Foundation DMF Reportdaniel_gfNo ratings yet

- High Court of Jharkhand, Ranchi Index: (Daily Cause List Dated 19.05.2020)Document39 pagesHigh Court of Jharkhand, Ranchi Index: (Daily Cause List Dated 19.05.2020)999.anuraggupta789No ratings yet

- Afi Competition Calander 2022Document1 pageAfi Competition Calander 2022ramanji kandulaNo ratings yet

- Watershed PresentationDocument19 pagesWatershed Presentationmamta19sharma100% (1)

- 64th Senior National Fixture RevisedDocument7 pages64th Senior National Fixture RevisedSwaroop JainNo ratings yet

- Introductive Meeting New MD MeetingDocument18 pagesIntroductive Meeting New MD MeetingVikas IndiaNo ratings yet

- Jharkhand: National Horticulture Mission Krishi Bhawan Campus, Kanke Road, Ranchi-834008Document62 pagesJharkhand: National Horticulture Mission Krishi Bhawan Campus, Kanke Road, Ranchi-834008Rishabh GuptaNo ratings yet

- Tribal Issues in India FinalDocument7 pagesTribal Issues in India FinalDevansh Dubey100% (1)

- Ifcb2009 10Document222 pagesIfcb2009 10srinath155@gmail.comNo ratings yet

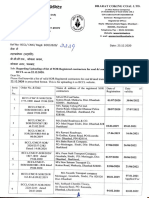

- SOR 3229 DT 23.12.2020Document3 pagesSOR 3229 DT 23.12.2020RR PatelNo ratings yet