Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Constructivism: Human Development (2014) - National Science Press

Uploaded by

c137Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Constructivism: Human Development (2014) - National Science Press

Uploaded by

c137Copyright:

Available Formats

Constructivism- 1

CONSTRUCTIVISM

By Andrew P. Johnson

Minnesota State University, Mankato

Andrew.johnson@mnsu.edu

www.OPDT-Johnson.com

This is an excerpt from my book: Education Psychology: Theories of Learning and

Human Development (2014). National Science Press: www.nsspress.com

CONSTRUCTIVISM

Constructivism is a theory of learning that aligns most closely with cognitive psychology;

however, it also seems to reinforce and be reinforced by research in the areas of cognitive

neuroscience, humanistic learning theory, and holistic learning theory. Remember, a theory is a

way to explain a set of facts. Different theories explain similar facts differently.

The Basics

Learning occurs when new knowledge and understanding is constructed based on what

we already know and believe (NRC, 2000). This is the essence of constructivism. We do not

simply replicate in our heads what we read, hear, or experience; rather, we use what’s in our

head to help us understand new information and construct meaning.

For example, this chapter contains information about constructivism. As you read below

you will use any related knowledge already contained in your LTM (semantic memory) along

with your own experiences as learners (episodic memory) to help you construct or build a

meaningful concept of constructivism. If you have an abundance of related knowledge and

experiences this well be fairly easy. If you have very little related knowledge and experiences,

you will have to work a little harder to build a meaningful concept. And since no two human

experiences are alike, no two conceptions of constructivism will be exactly the same.

Learning

What is learning? Some descriptors that align with cognitive learning theory are

provided below:.

Learning is an active process. When you build or construct something you can’t just sit

in a chair. You have to do something. In the same way, a constructivist perspective sees

learning as an active, not a passive process. You cannot be learned. You cannot be learned at.

Nobody can learn you. Instead, you must learn. It is something you must actively strive to do.

To illustrate, if you are simply reading the words on this page without making any

attempt to understand what the words might mean, it will be very hard for you to construct a

meaningful concept. Instead, you need to be actively involved in constructing meaning. This

means that as you read you have to (a) check for understanding as you read, (b) identify

interesting or important ideas, (c) make a conscious effort to connect this information with what

you already know about teaching and learning, (d) pause every once in a while to see if what you

are reading makes sense, (e) connect the information to your own experiences, and then (f) think

about possible applications for this new knowledge.

© Andrew P. Johnson, Ph.D.

Constructivism- 2

Real learning is meaningful. Here’s a question for you: If you memorized a list of

psychological terms but you did not understand any of them would you have learned? Answer:

yes. However, you would have engaged in what’s called rote learning, a very low quality of

learning. This is when information is taken in but there are little or no connections to anything

currently in LTM (see Figure 1). Rote learning does not lead to understanding or meaning and

thus, is fairly useless. In order to understand new information it must be connected to

information that is understood. This is called meaningful learning. As the name implies,

meaningful learning has meaning or makes sense and it can be easily encoded, stored, retrieved,

and applied. And, the more connections to known things that you can make the more meaningful

this new information becomes. Thus we see the importance of a having a well-organized body

of knowledge in the teaching and learning process (see below). We also see the importance of

connecting the new to the known when you are introducing a new topic.

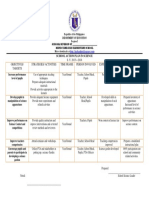

Figure 1. Rote and meaningful learning.

Memorizing is different from learning. We know that memory is important in

learning. We need to be able to be able to hold new information in STM. We need to be able to

encode and store new information in LTM. And, we need to be able to use knowledge currently

existing in LTM in order to understand new information. But memorizing is not the same as

learning. Again, you could memorize a list of psychological terms, but if they were meaningless

you would not have learned anything. Real learning involves creating meaning. There are many

memory strategies that can be helpful for recalling certain things (such as mnemonic devices).

But these are simply memory tools. Do not confuse memorizing with learning. Whether

reading, listening, doing, or experiencing, if you are not creating meaning you are not engaged in

meaningful learning. Real learning is associated with something. To be meaningful it makes

sense or carries some significance. To do this, new information must be connected to known

information.

Learning is a cognitive process. As described above, learning takes place inside the

head as new information combines with existing knowledge. This reflects Piaget’s description of

assimilation and accommodation. Assimilation occurs when new information adds to and

enhances existing knowledge structures or schemas. From a neurological perspective, this would

be when neural pathways are strengthened and neural networks are expanded. Accommodation

occurs when new information conflicts with existing knowledge or does not match any existing

knowledge structures or schemas. Old structures need to be modified. From a neurological

perspective, this would be when new neural pathways are formed and new neural networks are

created.

Since learning takes place inside the head, we can measure and observe only the effects

of learning, but not learning itself. We can never fully account for the new knowledge structures

created. As well, learning often goes far beyond what is taught or measured. That is, as students

© Andrew P. Johnson, Ph.D.

Constructivism- 3

use their background knowledge and experience to infer and fill in the blanks, the whole of what

they learn is usually far greater than the sum of the individual parts.

Learning is something humans do naturally. Humans are hard-wired to search for

meaning. We have a natural tendency to make sense of their world, to look for patterns, and to

creating meaning out of chaos. It is this natural tendency that has enabled our species to evolve

from the earliest times. Piaget described children as natural scientists who explore their world.

By acting upon the world the world acts upon them in terms of changing schema. When they

encounter new information that coincides with existing schema it enhances or expands these

cognitive structures (assimilation). When new information conflicts with current thinking it

creates a state of disequilibrium that can only be resolved by reforming old structures or creating

new ones (accommodation).

Learning is not a standardized process. Learners are not standardized products. Our

brains are all unique. We all process information and learn a little bit differently. We all bring

different knowledge and experiences to a learning experience. Since learning is not a

standardized process, it would be silly to assume that teaching could be a standardized process.

One size does not fit all when it comes to teaching strategies, pedagogy, approaches, or

methodology. Thus, insisting that all teachers utilize a standard approach reduces the amount of

real learning that takes place.

Learning is enhanced when it occurs in authentic situations or involves and

authentic task. The goal is for students to be able use knowledge and skills, not in school

environments, but out in the world (see ‘transfer’ below). Learners learn best when the

knowledge and skills taught in the setting or situation in which they will be used or which

replicate real life situations to the greatest degree. This is called situated learning. This means,

instead of assigning a grammar worksheet with a list of fill-in-the blank questions we would ask

students to write to express their ideas or describe their experiences (just like adults do in real

life) and then teach grammar in the context of their authentic writing. Also, we would teach

math and science using inquiry or problem-based learner.

The Importance of Knowledge

A constructivist view of learning places great emphasis on what students know. What

you know affects what you might know. Since meaningful learning involves connecting the new

to the known, the more we know the better we are able to learn. Among other things, a well-

organized body of knowledge in LTM improves problem solving, reasoning, reading

comprehension, and as we saw in Chapter 14, our ability to learn. Knowledge also affects our

ability to perceive and remember (Goldstein 2008).

One of the differences between experts and novices in any field is an organized body of

knowledge. Experts have acquired a great deal of content knowledge that is organized in LTM

in ways that reflect a deep understanding of the subject matter. This organization helps them

easily retrieve important aspect of knowledge when necessary with very little attention

(automaticity). It also helps them notice patterns and use chunking when working with

information in STM. In comparison, the knowledge base of a novice relative to a given area is

shallow and disjointed.

An important part of any teacher’s job is to help students develop an organized body of

knowledge. Some tips for this include the following:

• Teach using well-structured lessons that present knowledge in an organized fashion.

Strive to create a logical sequence of instructional events and links activities to instructional

objectives (Johnson, 2010).

© Andrew P. Johnson, Ph.D.

Constructivism- 4

• Use advanced organizers, graphic organizers, and concepts maps to show the structure

of what is to be learned or what was learned. Advanced organizers show students the structure

of or key points related to what is to be learned. Concept maps and graphic organizers show

students the hierarchical structure of a concept and how one thing relates to another.

• Use a well-structured organized curriculum that includes planned redundancy of key

concepts and important points.

• Instead of trying to cover too many subjects superficially, teach fewer subjects more in

depth (NRC, 2000).

Constructivist Teaching

Constructivism is a theory that describes how people construct knowledge and create their

view of the world (see below). There are a variety of teaching strategies that align with

constructivism and could be considered to be constructivist teaching practices. These include:

discovery learning, cooperative learning, inquiry learning, reading and writing workshop, and

problem-based learning (described in Book II – Advanced Pedagogy). One of the biggest

misconceptions of constructivist teaching is that it does not involve direct teaching, explicit

instruction, or lecture/telling. This is not the case. The difference between constructivist

teaching and some of the more top-down approaches is that a constructivist approach recognizes

that providing organized, well-structured information is only one part of creating effective

learning experiences.

Constructing Memories

What do you remember about what you did yesterday? Are you sure? Find a friend who

may have shared an experience with you. Ask that friend to list the details of that experience

while you do the same. Compare your lists. What do you notice about what was listed and in

what order?

According to the constructivist view, human memory, like knowledge, is constructed

using what we know and believe along with context, expectations, and past experiences

(Sternberg & Williams, 2009). Even though we think we are remembering events from our lives

exactly has they happened, our memories never exactly replicate. Instead, our memories

reconstruct a version of reality using all the information and experiences stored in LTM. Just as

we construct knowledge when we encode and store information, we do that same as we retrieve

information from LTM. Because of the emotional content, episodic memories are especially

susceptible to memory reconstruction.

RELATED VIDEO MINI-LECTURES

Constructivism 1: Overview of a Learning Theory

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nuS6E2mXqNE

Constructivism 2: Teaching Practices

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=W2c1WcM76eM

Constructivism Basics

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ELPsKhd9lWs

Schema Theory, Learning, and Comprehension

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V4_Kio9pPwE

© Andrew P. Johnson, Ph.D.

Constructivism- 5

Constructing Memories

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6uguEWRP6hA

References

Eggen P. & Kauchak, D. Educational psychology: Windows on classrooms (7th ed.). Upper

Saddle River, NJ: Pearson

Goldstein, E.B. (2008). Cognitive psychology (2nd ed.) Belmont, CA: Thomson Higher Education

Dabrowski, K. (1964). Positive disintegration. Boston: Little, Brown.

Piaget, J. (1983). Piaget’s theory. In P. Mussen (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology (4th ed.,

Vol. 1). New York: Wiley.

Silverman, L.K. (1993). The gifted individual. In L.K. Silverman (Ed.) Counseling the gifted

and talented. Denver, CO: Love Publishing Company, pp. 3-28.

Sisk, D. and Torrance, E.P. (2001). Spiritual intelligence: Developing higher consciousness.

Buffalo, NY: Creative Education Foundation Press.

Sternberg, R.J. & Williams, W.M. (2009). Educational psychology (2nd ed). Boston, MA:

Pearson.

Wallas, G. (1926). The art of thought. New York: Harcourt, Brace, and World.

© Andrew P. Johnson, Ph.D.

You might also like

- Walter Russell - The Secret of LightDocument163 pagesWalter Russell - The Secret of Lighttombosliekamp98% (53)

- Clifford W. Cheasley (1916) - Whats in Your Name - The Science of Letters and PDocument122 pagesClifford W. Cheasley (1916) - Whats in Your Name - The Science of Letters and Ppgeronazzo8450100% (22)

- How to Teach Kids Anything: Create Hungry Learners Who Can Remember, Synthesize, and Apply KnowledgeFrom EverandHow to Teach Kids Anything: Create Hungry Learners Who Can Remember, Synthesize, and Apply KnowledgeNo ratings yet

- zero-THE THEORY OF INVOLUTIONDocument8 pageszero-THE THEORY OF INVOLUTIONc137No ratings yet

- Qi-Gong and Kuji-InDocument117 pagesQi-Gong and Kuji-Intelecino100% (38)

- Teutonic Religion - Kveldulf GundarssonDocument196 pagesTeutonic Religion - Kveldulf GundarssonAshleeScholefieldNo ratings yet

- Cognitive DevelopmentDocument9 pagesCognitive DevelopmentAnonymous rkZNo8No ratings yet

- (Ebook - Alchimia - EnG) - AA - VV - Alchemy Journal Anno 2 n.3Document17 pages(Ebook - Alchimia - EnG) - AA - VV - Alchemy Journal Anno 2 n.3blueyes247100% (2)

- Learning To LearnDocument27 pagesLearning To Learnmichaeleslami100% (2)

- Learning TheoriesDocument21 pagesLearning Theorieswinwin86No ratings yet

- Zero-The Power of ZenDocument7 pagesZero-The Power of Zenc137No ratings yet

- Body and Mind A History and A Defense of Animism PDFDocument442 pagesBody and Mind A History and A Defense of Animism PDFc137No ratings yet

- Knowledge Paper XDocument25 pagesKnowledge Paper Xc137No ratings yet

- Learning To Learn (Mental Tools To Master Any Subject) PDFDocument27 pagesLearning To Learn (Mental Tools To Master Any Subject) PDFPep FloNo ratings yet

- Zero - The Universal MotherDocument2 pagesZero - The Universal Motherc137100% (1)

- The Principles of Light and Color by Edwin D Babbitt, 1878Document287 pagesThe Principles of Light and Color by Edwin D Babbitt, 1878popmolecule100% (40)

- Zero-What Happens When We AscendDocument5 pagesZero-What Happens When We Ascendc137No ratings yet

- Zero-True Reality CreationDocument26 pagesZero-True Reality Creationc1370% (1)

- Swadhisthana - The Sacral Chakra: DoshasDocument10 pagesSwadhisthana - The Sacral Chakra: Doshasc137No ratings yet

- Swadhisthana - The Sacral Chakra: DoshasDocument10 pagesSwadhisthana - The Sacral Chakra: Doshasc137No ratings yet

- Tesla'S Fbi File, Enclosure 1Document18 pagesTesla'S Fbi File, Enclosure 1paroalonsoNo ratings yet

- WildeStuartGodsGladiators PDFDocument190 pagesWildeStuartGodsGladiators PDFc137100% (1)

- ConstructivismDocument29 pagesConstructivismAlysa Quintanar100% (1)

- Action Plan in Araling Panlipunan School Year 2019-2020Document2 pagesAction Plan in Araling Panlipunan School Year 2019-2020Endlesdiahranf B OzardamNo ratings yet

- IPCRF DEVELOPMENT PLANsumalpongDocument2 pagesIPCRF DEVELOPMENT PLANsumalpongBrigette Darren Colita75% (4)

- Personal Philosophy of Teaching That Is Learner-CenteredDocument2 pagesPersonal Philosophy of Teaching That Is Learner-CenteredDonna Welmar Tuga-onNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning TheoriesDocument5 pagesTeaching and Learning TheoriesJulie Ann Gerna100% (3)

- ConstructivismDocument5 pagesConstructivismMaria Dominique DalisayNo ratings yet

- MYP Guide For Parents - EnglishDocument2 pagesMYP Guide For Parents - EnglishZachary JonesNo ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning ProcessDocument5 pagesTeaching and Learning ProcessQurban NazariNo ratings yet

- Teaching For Conceptual Change PDFDocument25 pagesTeaching For Conceptual Change PDFMat TjsNo ratings yet

- Thomas Karlsson ThagirionDocument3 pagesThomas Karlsson ThagirionSheshito El No MuertitoNo ratings yet

- School Action Plan in Science PDFDocument1 pageSchool Action Plan in Science PDFAnacel FaustinoNo ratings yet

- Behaviourist TheoryDocument4 pagesBehaviourist TheorykhairulNo ratings yet

- RPMS Porfolio Template (A4)Document32 pagesRPMS Porfolio Template (A4)Judith AbogadaNo ratings yet

- Constructivist Learning TheoryDocument13 pagesConstructivist Learning TheoryJan Alan RosimoNo ratings yet

- Script Presentatio FilsafatDocument4 pagesScript Presentatio FilsafatRetni WidiyantiNo ratings yet

- A Constructivist View of Science EducationDocument1 pageA Constructivist View of Science EducationZamfirescu Vladimir-AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Es of LearningDocument13 pagesEs of Learningjohnmer BaldoNo ratings yet

- Taller Constructivismo y RespuestasDocument4 pagesTaller Constructivismo y RespuestasMaylin GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Constructivism + Affective Factors + AcquisitionDocument13 pagesConstructivism + Affective Factors + AcquisitionPhạm Cao Hoàng My DSA1211No ratings yet

- EseuDocument4 pagesEseuIurie CroitoruNo ratings yet

- Forum PostsDocument7 pagesForum Postsapi-375720436No ratings yet

- AngieDocument3 pagesAngieShine Shine LawaganNo ratings yet

- Reflection PaperDocument23 pagesReflection PaperElaine Mhanlimux AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- On Completion-Reflection Paper On Educ 202-Seminar in Educational PsychologyDocument31 pagesOn Completion-Reflection Paper On Educ 202-Seminar in Educational PsychologyElaine Mhanlimux AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- The Learning Approaches of The Grade 9 Students of Concordia College S.Y. 2017 2018Document64 pagesThe Learning Approaches of The Grade 9 Students of Concordia College S.Y. 2017 2018Cheng SerranoNo ratings yet

- PDQ AssignmentDocument7 pagesPDQ AssignmentOkoh maryNo ratings yet

- Psychological Foundation in EducationDocument4 pagesPsychological Foundation in EducationKenny Rose Tangub BorbonNo ratings yet

- Learning Point: Theories of LearningDocument20 pagesLearning Point: Theories of LearningJoan Conje BonaguaNo ratings yet

- Constructivism AcquisitionDocument12 pagesConstructivism AcquisitionThanh ThanhNo ratings yet

- AssumptionDocument3 pagesAssumptionsuzetteNo ratings yet

- 4 Instructional Design and Technology Learning TheoriesDocument19 pages4 Instructional Design and Technology Learning TheoriesCaila Jean MunarNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2.BDocument22 pagesChapter 2.BMaria Fatima GalvezNo ratings yet

- Session 5: Prior Knowledge Prior KnowledgeDocument5 pagesSession 5: Prior Knowledge Prior KnowledgeJamaica PalloganNo ratings yet

- Apa Ini Upload TerusDocument3 pagesApa Ini Upload TerusMuhammad Fadly HafidNo ratings yet

- Lopez Book ReportDocument3 pagesLopez Book Reportapi-495365721No ratings yet

- Constructivist Learning Theory (Ness)Document4 pagesConstructivist Learning Theory (Ness)Yam YamNo ratings yet

- Handout-2 HBO Briones-NL.Document12 pagesHandout-2 HBO Briones-NL.ANGELA FALCULANNo ratings yet

- Guide QuestionsDocument2 pagesGuide QuestionsMariline LeeNo ratings yet

- Constructivist Learning TheoryDocument2 pagesConstructivist Learning TheoryElisha BhandariNo ratings yet

- Constructivist Learning TheoryDocument5 pagesConstructivist Learning TheoryTadeo, Vincent Carlo Q.No ratings yet

- Philosophy of Adolescent LearningDocument17 pagesPhilosophy of Adolescent Learningapi-312799145No ratings yet

- Module 14-18Document4 pagesModule 14-18Erika Joy GutierrezNo ratings yet

- Francis Sam L. SantañezDocument5 pagesFrancis Sam L. SantañezFrancis Sam SantanezNo ratings yet

- Lec 3Document19 pagesLec 3geetha megharajNo ratings yet

- Self-Regulated Learning Research PaperDocument22 pagesSelf-Regulated Learning Research PaperAnrewNo ratings yet

- Humanism, Constructionism, ConnectivismDocument5 pagesHumanism, Constructionism, Connectivismregine mae cala-orNo ratings yet

- Human Learning AnalysisDocument3 pagesHuman Learning AnalysisMilton MartinezNo ratings yet

- What Is TeachingDocument26 pagesWhat Is TeachingGiezyle MantuhanNo ratings yet

- Principles of ConstructivismDocument7 pagesPrinciples of Constructivism中华人民共和国People Republic of ChinaNo ratings yet

- BEHAVIORISMDocument10 pagesBEHAVIORISMakademik poltektransNo ratings yet

- Discuss Five Comptemporary Advanced LearningtheoriesDocument11 pagesDiscuss Five Comptemporary Advanced LearningtheoriesOgechi AjaaNo ratings yet

- Transcript (Confident Learner)Document7 pagesTranscript (Confident Learner)dorklee9080No ratings yet

- Cognitive Science Final Paper 1Document5 pagesCognitive Science Final Paper 1api-516330508No ratings yet

- BehaviorismDocument5 pagesBehaviorismMarian Joyce LermanNo ratings yet

- Theories of LearningDocument13 pagesTheories of Learningbasran87No ratings yet

- Theory LensDocument5 pagesTheory LensLiezel PlanggananNo ratings yet

- TheoristpaperDocument6 pagesTheoristpaperapi-346875883No ratings yet

- What Is Educational PsychologyDocument4 pagesWhat Is Educational PsychologyRICKY SALABENo ratings yet

- Topics: Constructivist Learning TheoriesDocument4 pagesTopics: Constructivist Learning TheoriesAira Mae AntineroNo ratings yet

- Cognitivism 1 PDFDocument9 pagesCognitivism 1 PDFbaksiNo ratings yet

- The Unified Learning Model: How Motivational, Cognitive, and Neurobiological Sciences Inform Best Teaching PracticesFrom EverandThe Unified Learning Model: How Motivational, Cognitive, and Neurobiological Sciences Inform Best Teaching PracticesNo ratings yet

- Mayette InsightsDocument21 pagesMayette InsightsJo Honey HugoNo ratings yet

- Zero-The Highest in The RoomDocument1 pageZero-The Highest in The Roomc137No ratings yet

- Zero-Mudras For The Primary ChakraDocument6 pagesZero-Mudras For The Primary Chakrac137No ratings yet

- Zero - We Came Back For YouDocument1 pageZero - We Came Back For Youc137No ratings yet

- Zero - The Universal Current ZuluDocument5 pagesZero - The Universal Current Zuluc137No ratings yet

- Zero SoulDocument1 pageZero Soulc137No ratings yet

- The Universal Current Show - Episode 4 - How To Get Out of The Body and What Exists ThereDocument2 pagesThe Universal Current Show - Episode 4 - How To Get Out of The Body and What Exists Therec137No ratings yet

- Collected Fruits of Occult TeachingDocument316 pagesCollected Fruits of Occult TeachingjNo ratings yet

- Thai-Cambodian Culture - Relationship Through ArtsDocument350 pagesThai-Cambodian Culture - Relationship Through ArtsAnimesh_Singh1No ratings yet

- Hermetic TriumphDocument40 pagesHermetic Triumphjordon garaldNo ratings yet

- Hermetic Triumph - The Ancient War of The KnightsDocument8 pagesHermetic Triumph - The Ancient War of The Knightsjordon garaldNo ratings yet

- The 11 Tenets of Ain PDFDocument1 pageThe 11 Tenets of Ain PDFc137No ratings yet

- Tertullian's Letter To The MartyrsDocument5 pagesTertullian's Letter To The MartyrskalaratriNo ratings yet

- (TTL1 LESSON 1) KimlafuenteDocument5 pages(TTL1 LESSON 1) KimlafuenteKim Daryll LafuenteNo ratings yet

- Astrid M. AlvarezDocument2 pagesAstrid M. Alvarezapi-458917886No ratings yet

- H FS1 Activity 4 EditedDocument7 pagesH FS1 Activity 4 EditedRayshane EstradaNo ratings yet

- Detailed Lesson Plan (DLP) FormatDocument2 pagesDetailed Lesson Plan (DLP) FormatLily Anne Ramos MendozaNo ratings yet

- Session Plan SampleDocument2 pagesSession Plan SampleReina MatanguihanNo ratings yet

- PST SubjectDocument2 pagesPST SubjectCarol ElizagaNo ratings yet

- Module 1 The Impact of Technology V2-1Document27 pagesModule 1 The Impact of Technology V2-1Grizl Fae VidadNo ratings yet

- 25 Formative Assessments Judith DodgeDocument103 pages25 Formative Assessments Judith DodgeTrotta EelianavNo ratings yet

- TBT Meeting Minutes FormDocument2 pagesTBT Meeting Minutes Formapi-233836366No ratings yet

- Deped Mission VissionDocument3 pagesDeped Mission VissionMarinel CanicoNo ratings yet

- Blended Learning and Personalized Learning - Written Report (Mr. Habon and Ms. Sanchez)Document2 pagesBlended Learning and Personalized Learning - Written Report (Mr. Habon and Ms. Sanchez)Michaela Kristelle Balanon SanchezNo ratings yet

- Assessment in Special EducationDocument15 pagesAssessment in Special EducationpandaNo ratings yet

- Individual 5e Lesson Plan Social Studies 2Document3 pagesIndividual 5e Lesson Plan Social Studies 2api-642963927No ratings yet

- Lesson Plans - Weebly Cirg 644 l1Document2 pagesLesson Plans - Weebly Cirg 644 l1api-542550614No ratings yet

- 7 Things Students Want To KnowDocument1 page7 Things Students Want To Knowapi-290562983No ratings yet

- Laporan Kursus KSSM EnglishDocument20 pagesLaporan Kursus KSSM EnglishRizalhanafi YusofNo ratings yet

- 2nd Quarter DLL MAPEH (MUSIC)Document3 pages2nd Quarter DLL MAPEH (MUSIC)Cristel Anne A. Llamador100% (1)

- Rancangan Pengajaran Harian Pendidikan Khas - Masalah PembelajaranDocument2 pagesRancangan Pengajaran Harian Pendidikan Khas - Masalah PembelajaransaravananNo ratings yet

- English Language Teaching (ELT) Curriculum Reforms in MalaysiaDocument2 pagesEnglish Language Teaching (ELT) Curriculum Reforms in Malaysiaamat911No ratings yet

- IV Day 9Document3 pagesIV Day 9Joevelyn Krisma CubianNo ratings yet

- DLL - MIL - Week 1 Feb 13-17Document7 pagesDLL - MIL - Week 1 Feb 13-17Chai Sacayanan-PascualNo ratings yet

- Mes 112Document5 pagesMes 112Rajni KumariNo ratings yet

- National Public School - WhitefieldDocument5 pagesNational Public School - WhitefieldAnonymous wnJV2QZVTrNo ratings yet

- Harriet Amihere Multimedia Audio or Video Lesson Idea Template2022Document3 pagesHarriet Amihere Multimedia Audio or Video Lesson Idea Template2022api-674932502No ratings yet