Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Muscle Dysmorphia: Could It Be Classified As An Addiction To Body Image?

Uploaded by

Clau CobosOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Muscle Dysmorphia: Could It Be Classified As An Addiction To Body Image?

Uploaded by

Clau CobosCopyright:

Available Formats

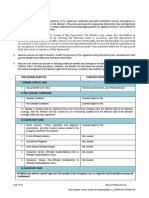

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/260403509

Muscle dysmorphia: Could it be classified as an addiction to body image?

Article in Journal of Behavioral Addictions · December 2014

DOI: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.001

CITATIONS READS

27 217

3 authors:

Gillian W Shorter Mark D Griffiths

Ulster University Nottingham Trent University

64 PUBLICATIONS 1,046 CITATIONS 1,152 PUBLICATIONS 35,581 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Andy Foster

National Health Service

3 PUBLICATIONS 29 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Exercise Addiction View project

Exercise addiction in adolescents View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Gillian W Shorter on 28 February 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

DEBATE DOI: 10.1556/JBA.3.2014.001

Muscle dysmorphia: Could it be classified as an addiction

to body image?

ANDREW C. FOSTER1, GILLIAN W. SHORTER2,3 and MARK D. GRIFFITHS4*

1

School of Experimental Psychology, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK

2

Bamford Centre for Mental Health and Wellbeing, University of Ulster, Londonderry, UK

3

MRC All Ireland Trials Methodology Hub, University of Ulster, Londonderry, UK

4

International Gaming Research Unit, Division of Psychology, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK

(Received: October 22, 2013; revised manuscript received: October 24, 2013; accepted: October 25, 2013)

Background: Muscle dysmorphia (MD) describes a condition characterised by a misconstrued body image in which

individuals who interpret their body size as both small or weak even though they may look normal or highly muscu-

lar. MD has been conceptualized as a type of body dysmorphic disorder, an eating disorder, and obsessive–compul-

sive disorder symptomatology. Method and aim: Through a review of the most salient literature on MD, this paper

proposes an alternative classification of MD – the ‘Addiction to Body Image’ (ABI) model – using Griffiths (2005)

addiction components model as the framework in which to define MD as an addiction. Results: It is argued the addic-

tive activity in MD is the maintaining of body image via a number of different activities such as bodybuilding, exer-

cise, eating certain foods, taking specific drugs (e.g., anabolic steroids), shopping for certain foods, food supple-

ments, and the use or purchase of physical exercise accessories). In the ABI model, the perception of the positive ef-

fects on the self-body image is accounted for as a critical aspect of the MD condition (rather than addiction to exer-

cise or certain types of eating disorder). Conclusions: Based on empirical evidence to date, it is proposed that MD

could be re-classified as an addiction due to the individual continuing to engage in maintenance behaviours that may

cause long-term harm.

Keywords: muscle dysmorphia, behavioral addiction, body dysmorphic disorder, body image, obsessive–compul-

sive disorder, eating disorder

INTRODUCTION a type of eating disorder (e.g. Jones & Morgan, 2010; Maida

& Armstrong, 2005; Murray, Rieger, Touyz & De la Garza

Muscle dysmorphia (MD) describes a condition character- Garcia, 2010; Nieuwoudt, Zhou, Coutts & Booker, 2012;

ised by a misconstrued body image in which individuals in- Pope, Gruber, Choi, Olivardia & Phillips, 1997; Pope et al.,

terpret their body size as both small and weak even though 2005). In this paper, the limitations of these classification

they may look normal or even be highly muscular (Pope et approaches will be discussed, and an alternative model is

al., 2005). Those experiencing the condition typically strive proposed – the ‘Addiction to Body Image’ (ABI) model.

for maximum fat loss and maximum muscular build. MD

can have potentially negative effects on thought processes

including depressive states, suicidal thoughts, and in ex- HOW IS MUSCLE DYSMORPHIA

treme cases suicide attempts (Pope et al., 2005). These nega- CURRENTLY CLASSIFIED?

tive psychological states have also been linked with concur-

rent use of Appearance and Performance Enhancing Drugs BDD is characterised by a preoccupation with a perceived

(APED) including Anabolic Androgenic Steroids (AAS) defect in physical experience that leads to a substantial func-

(Mosley, 2009; Pope et al., 2005). The use of these sub- tional impairments (American Psychiatric Association,

stances may not just relate to body image, but also social or 2013). Such a definition can include MD and in the latest

sexual aspects such as producing an enhanced libido or a DSM-5, muscle dysmorphia was added as a specifier to the

sense of physical and psychological wellbeing (Cohen, Col- BDD diagnostic criteria. This representation of Muscle

lins, Darkes & Gwartney, 2007). Dysmorphia is supported by authors such as Pope et al.

MD was originally categorised by Pope, Katz and Hud- (1997). In the context of a preoccupation with the belief that

son (1993) as Reverse Anorexia Nervosa, due to characteris- their body is not sufficiently muscular and lean, and exces-

tic symptoms in relation to body size. It has been considered sive attention to exercise, lifting weights and diet (possibly

to be part of the spectrum of Body Dysmorphic Disorders including supplements and AAS), the criteria outlined by

(BDD); one of a range of conditions that tap into issues sur- Pope et al. (1997) – for which two or more need to be present

rounding body image and eating behaviours (McFarland & for a diagnosis of the condition – are:

Karninski, 2008). Parallels have also been drawn with

Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder (OCD) given some simi- * Corresponding author: Mark D. Griffiths, Professor of Gambling

larities in symptom expression like ritualistic activity Studies; International Gaming Research Unit, Psychology Divi-

(Phillips, 1998). Consequently, there is a lack of consensus sion, Nottingham Trent University, Burton Street, Nottingham,

amongst researchers whether MD is a form of BDD, OCD or NG1 4BU, UK; E-mail: mark.griffiths@ntu.ac.uk

© 2014 Akadémiai Kiadó, Budapest

Foster et al.

1. Giving up important activities of a social, work or recre- AN ALTERNATIVE CLASSIFICATION:

ational nature due to a strong need to maintain activities ‘ADDICTION TO BODY IMAGE’ MODEL

in relation to workouts and diet control.

2. Active avoidance of situations where their body is dis-

played to others, and an intense distress/anxiety of these The ‘Addiction to Body Image’ (ABI) model attempts to

situations when they are unavoidable. provide an operational definition and to introduce a standard

3. Clinically significant distress arising from pre-occupa- assessment across the research area. The ABI model uses the

tion with their body fat, size, or musculature. addiction components model of Griffiths (2005) as the

4. A continuation of dietary control and exercise, despite framework in which to define muscle dysmorphia as an ad-

the knowledge of adverse physical or psychological con- diction. For the purposes of this paper, body image is de-

sequences. fined as a person’s “perceptions, thoughts and feelings about

his or her body” (Grogan, 2008, p. 3). The addictive activity

The International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10) also is the maintaining of body image via a number of different

classifies MD with other BDD conditions in section F45.2 activities such as bodybuilding, exercise, eating certain

entitled hypochondriacal disorder. Essential features in- foods, taking specific drugs (e.g., anabolic steroids), shop-

clude somatic complaints, preoccupation, and distress in re- ping for certain foods, food supplements, and purchase or

lation to physical appearance. The category appears to refer use of physical exercise accessories). Addiction is defined as

to a heterogeneous range of conditions, and the somatoform the use of a substance or activity that becomes all-encom-

description of the MD condition appears unwarranted. passing to the user and comprises all six of Griffiths’ (2005)

Somatoform disorders relate to physical symptomatology addiction components. Each of these components is de-

that is difficult to explain in terms of physical disease, sub- scribed below in the context of MD symptomatology and be-

stance use, or other mental disorder. Mosley (2009) consid- havioural maintenance.

ered the ‘somatoform’ description incongruent with MD;

Maida and Armstrong (2005) concurred, given MD symp- Salience

toms were found to be unrelated to symptoms of

somatoform disorder in men who regularly lifted weights. A person with an ABI may: (i) have cognitive disturbances

Other classifications consider MD to be part of the ob- that lead to a total preoccupation with activities that maintain

sessive–compulsive disorder symptomatology. A shift of body image such as physical training and eating according to

BDDs to be classified as OCD spectrum disorders was con- a strict dietary intake (Veale, 2004), (ii) be able to perform

sidered but rejected due to a lack of evidence (Phillips & other tasks such as work and shopping (explained by reverse

Hollander, 1996). There are similarities in symptom expres- salience – see below) as these tasks will be designed and

sion including intrusive fear, ritualistic actions or obsessions built around being able to engage in specific body image

in the course of the illness (Bienvenu et al., 2000; Phillips, maintenance behaviours such as physical exercising and eat-

1998; Phillips, Dwight & McElroy, 1998; Phillips, ing (Olivardia, Pope & Hudson, 2000), and (iii) be able to

Gunderson, Mallya, McElroy & Carter, 1998; Rosen, Reiter manipulate their personal situation to ensure they can per-

& Orosan, 1995; Zimmerman & Mattia, 1998). Despite form these maintenance tasks (Mosley, 2009). The individ-

overlaps with symptoms and comorbid conditions, Phillips, ual with ABI may even change or forego career opportuni-

Gunderson et al. (1998) note important disparities in social ties and other daily activities as it may reduce their ability to

isolation, delusions, and differences in insight that cast train or control eating behaviour during the day (Murray

doubt on MD’s suitability for classification on the OCD et al., 2010).

spectrum.

There are also some parallels drawn to the eating disor- Reverse salience

ders such as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa given the

extent of attention to diet and exercise, and dissatisfaction If the person with ABI cannot engage in maintenance behav-

with body image (Mangweth et al., 2001; Olivardia, Pope, iours such as training or eating regimes, their thought pro-

Mangweth & Hudson, 1995). Eating disorders as presented cesses are likely to be excessively preoccupied by the need

in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual are characterised by to carry out the desired behaviours to maintain body image

severe disturbances in eating behaviour and a preoccupation (Olivardia et al., 2000). This may result in the manifestation

with eating (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The of physical symptoms. More specifically, the cognitive dis-

rigour in which an individual pursues the body ideal is simi- turbance creates a negative thought process that facilitates

lar amongst the different types of eating disorder and MD. the manifestation of physical symptoms (e.g., shakes, sweat-

However, the goals being pursued are very different (e.g. the ing, nausea, etc.) as seen in other addictions. Due to some of

intrusive fears around weight relate to gain in Anorexia the dietary restrictions the person with ABI places upon their

Nervosa, but loss in MD). Additionally, it could be consid- body, physical symptoms such as fainting and falling uncon-

ered that a secondary feature of the MD condition is the dis- scious may be present due to low blood sugar levels.

ordered eating (Olivardia, 2001), and thus classification as a

disorder of ‘eating’ is not sufficient. Other authors (e.g., Mood modification

Demetrovics & Griffiths, 2012) have mentioned that MD

could perhaps be classed as an addiction although there was For an individual with ABI, being able to engage in the

limited explanation. maintenance behaviours brings a sense of reward. As a con-

sequence, training and food intake (either restrictive or

over-eating) should facilitate the release of endorphins into

the bloodstream, which would increase positive mood. The

physical act of engaging in physical exercise and training

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

Muscle dysmorphia

(whether cardio- or weight-based) may produce a physical the long-term, the addiction will detract from their overall

state whereby the muscles are enriched with blood (which at quality of life.

their biggest is known as a ‘pump’). This pump brings a

sense of euphoria and happiness to the person (Elliot, Relapse

Goldberg, Watts & Orwoll, 1983).

The ABI model proposes that engaging in the mainte- If the person with ABI manages to stop the maintenance be-

nance behaviours – for example weight training – will create haviours for a period of time, they may be susceptible to trig-

a chemical high created by the body though the release of gers to re-engage in the behaviours again. CBT approaches

chemicals such as endorphins (Griffiths, 1997). A person for treatment of MD include aspects which address triggers

with ABI will desire these chemical changes and this may or reinforcing behaviour, and reducing stress around main-

have the same effect (both physiologically and psychologi- taining body image to prevent likelihood of relapse (Grieve,

cally) as other psychoactive substances. Once their mainte- Truba & Bowersox, 2009). When a person with ABI re-en-

nance behaviours have been completed, the person’s mood gages with behaviours again, they may go straight back into

will relax due to completion of the activity, and the person previous destructive training and eating patterns.

may also have a feeling of utopia, a sense of inner peace, or The ABI model differs from other addiction models in

an exceptional high. This feeling has been linked to the use relation to the primary and secondary dependencies. For in-

of AASs in gym training (Mosley, 2009). stance, in exercise addiction, the individual has the primary

The person with ABI will need to control their food in- goal of exercising, and the cognitive dysfunction in this con-

take (i.e., less or more protein and carbohydrates). The ABI dition is the act of exercising in, and of, itself (Berczik et al.,

model proposes this will become a secondary dependence 2012). If the person loses weight or increases their body size

due to the food intake being part of the process to maintain through their exercise, this is seen as a secondary depend-

the primary dependence (i.e., the sculpting of the body). ence as it is a natural consequence of the primary depend-

This will be due to the body adapting to the amount of calo- ence and is not the primary goal. In MD, the primary de-

ries it is being fed, but also due to requirement of being pendence is maintenance in behaviours that facilitate body

lighter or heavier – and for longer – which in turn will allow size change due to the cognitive dysfunction of negative per-

the person to obtain the desired body shape. ceptions of their body image. Exercise and/or dietary con-

trols are the secondary dependence as they assist in achiev-

Tolerance ing the primary goal of maintaining their desired body size

and composition. In addition, exercise addiction tends to re-

The person with ABI may need to increase the levels and in- late to compulsive aerobic exercise, with the endorphin rush

tensity of the training or the food restriction (i.e., the mainte- from the physical exertion rather than a reward from phy-

nance behaviours) to achieve the desired physiological sique change. Pope et al. (1997) also note that (to a degree)

and/or psychological effects. This can be achieved through aerobic exercise may be avoided by those with MD as it may

different training strategies or by the consumption of differ- reduce muscle size.

ent foods. In some circumstances, this may be achieved In the ABI model, the perception of the positive effects

through the use of psychoactive substances such as AASs or on the self-body image is accounted for as a critical aspect of

other food inhibiting drugs. Record keeping of training ses- the MD condition. The maintenance behaviours of those

sions and seeking out changes in activities may assist the in- with ABI may include healthy changes to diet or increases in

dividual in combatting the effects of tolerance (Mosley, exercise. However, such behaviours can hide or mislead

2009). those with ABI away from the negative thought processes

that are driving their addiction. It is in the cognitive dysfunc-

Withdrawal tion of MD where we believe there is a pathological issue,

and why the field has encountered problems with the criteria

The person with ABI is expected to have negative physical for the condition. The attempt to explain MD in the same

and/or psychological effects if they are unable to engage in manner as other BDDs may not be adequate due to the cog-

the maintenance activities. This would be likely to include nitive dysfunction occurring in the context of the potentially

one or more psychological and/or physical components positive physical effects via improvements in shape, tone,

(Griffiths, 2005) such as intense moodiness and irritability, and/or health of the body.

anxiety, depression, nausea, and stomach cramps. They will The ABI model supports the findings of Pope et al.

not be able to just stop the maintenance behaviours without (2005); there is a difference in the cognitive dysfunction

experiencing one or more of these symptoms. with a misconstrued self-body image compared to other

BDDs. The cognitive dysfunction causes the individual with

Conflict MD to have a misconstrued view of their own body image,

and the person may believe they are small and puny. This

The person with ABI becomes focused on their maintenance negative mindset has the potential to cause depression and

behaviours of training and/or eating. These behaviours can other disorders, and may facilitate the addiction. Unlike

become all consuming, and the need to train, control diet, other conceptualizations of MD in the BDD literature, we

and exercise may conflict with their family, their work, the would argue that the agent of the addiction is the perceived

use of resources (e.g., money) and their life in general. An body image that is maintained by engaging in secondary be-

individual quoted in Mosley (2009) noted “bodybuilding is haviours such as specific types of physical activity and food.

my life, so I make sacrifices elsewhere” (p. 194). In some The most important thing in the life of someone with MD is

cases of the addiction, the process is thought have healthy how their body looks (i.e., their body image). The behav-

physical consequences and add to life in the short-term, in iours that the person with MD engages in (such as excessive

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

Foster et al.

exercise or disordered eating) are merely the vehicles by 1,955 male adult non-medical anabolic steroid users in the

which their addiction (i.e., their perceived body image) is United States. Journal of the International Society of Sports

maintained. Nutrition, 4, 12–26.

Based on empirical evidence to date, we propose that Demetrovics, Z. & Griffiths, M. D. (2012). Behavioral addictions:

Muscle Dysmorphia could be re-classified as an addiction Past, present and future. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 1,

due to the individual continuing to engage in maintenance 1–2.

behaviours that cause long-term psychological damage. Elliot, D. L., Goldberg, L., Watts, W. J. & Orwoll, E. K. (1983).

More research is needed to explore the possibilities of MD Resistance exercise and plasma beta-endorphin/beta-lipo-

as an addiction, and how this particular addiction is linked to trophin immunoreactivity. Life Sciences, 37, 515–518.

substance use and other comorbid health conditions. Contro- Grieve, F. G., Truba, N. & Bowersox, S. (2009). Etiology, assess-

versy about the conceptual measurement of the condition, ment, and treatment of muscle dysmorphia. Journal of Cogni-

tive Psychotherapy. 23, 306–314.

has led to a number of different scales adapted from different

Griffiths, M. D. (1997). Exercise addiction: A case study. Addic-

criteria that may not fully measure the experience of MD

tion Research, 5, 161–168.

(Cafri & Thompson, 2007). However, a group of questions

Griffiths, M. D. (2005). A ‘components’ model of addiction within

that might test the applicability of the ABI approach to mea- a biopsychosocial framework. Journal of Substance Use, 10,

suring and conceptualising MD have not been asked. Ques- 191–197.

tionnaires such as the Exercise Addiction Inventory Griffiths, M. D., Szabo, A. & Terry, A. (2005). The Exercise Ad-

(Griffiths, Szabo & Terry, 2005; Terry, Szabo & Griffiths, diction Inventory: A quick and easy screening tool for health

2004) and the Bergen Work Addiction Scale (Andreassen, practitioners. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 39, 30–31.

Griffiths, Hetland & Pallesen, 2012) could be adapted to fit Grogan, S. (2008). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfac-

MD characteristics. Adequate conceptualisation is key to tion in men, women, and children. London: Routledge.

explore the clinically relevant condition (Kuennen & Jones, W. & Morgan, J. (2010). Eating disorders in men: A review

Waldron, 2007). This new ABI approach may also have im- of the literature. Journal of Public Mental Health, 9, 23–31.

plications for diagnostic systems around similar conditions Kuennen, M. R. & Waldron, J. J. (2007). Relationships between

such as other BDDs or eating disorders. Theoretical and em- specific personality traits, fat free mass indices, and the muscle

pirical work exploring these in an addiction context would dysmorphia inventory. Journal of Sport Behavior, 30,

be welcomed. 453–461.

Maida, D. M. & Armstrong, S. L. (2005). The classification of

muscle dysmorphia. International Journal of Men’s Health, 4,

73–91.

Funding source: None. Mangweth, B., Pope, H. G., Jr., Kemmler, G., Ebenbichler, C.,

Hausmann, A., De Col, C., Kreutner, B., Kinzl, J. & Biebl, W.

Authors’ contribution: All authors contributed to the writing (2001). Body image and psychopathology in male body-

of the paper. The paper was based on an idea originally for- builders. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 70, 38–43.

mulated by the first author. The second and third authors McFarland, M. B. & Karninski, P. L. (2008). Men, muscles, and

subsequently developed the idea. mood: The relationship between self-concept, dysphoria, and

body image disturbances. Eating Behaviours, 10, 68–70.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of inter- Mosley, P. E. (2009). Bigorexia: Bodybuilding and muscle

est. dysmorphia. European Eating Disorders Review, 17, 191–198.

Murray, S. B., Rieger, E., Touyz, S. W. & De la Garza Garcia, Y.

(2010). Muscle dysmorphia and the DSM-V conundrum:

Where does it belong? International Journal of Eating Disor-

REFERENCES ders, 43, 483–491.

Nieuwoudt, J. E., Zhou, S., Coutts, R. A. & Booker, R. (2012).

American Psychiatric Association (2013). Diagnostic and statisti- Muscle dysmorphia: Current research and potential classifica-

cal manual of mental disorders – Text revision (Fifth ed.). tion as a disorder. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 13,

Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 569–577.

Andreassen, C. S., Griffiths, M. D., Hetland, J. & Pallesen, S. Olivardia, R. (2001). Mirror, mirror on the wall, who’s the largest

(2012). Development of a Work Addiction Scale. Scandina- of them all? The features and phenomenology of muscle

vian Journal of Psychology, 53, 265–272. dysmorphia. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 9, 254–259.

Berczik, K., Szabó, A., Griffiths, M. D., Kurimay, T., Kun, B. & Olivardia, R., Pope, H. G., Jr., Mangweth, B. & Hudson, J. I.

Demetrovics, Z. (2012). Exercise addiction: Symptoms, diag- (1995). Eating disorders in college men. American Journal of

nosis, epidemiology, and etiology. Substance Use and Misuse, Psychiatry, 152, 1279–1285.

47, 403–417. Olivardia, R., Pope, H. H. & Hudson, J. I. (2000). Dysmorphia in

Bienvenu, O. J., Samuels, J. F., Riddle, M. A., Hoen-Saric, R., male weightlifters: A case-control study. American Journal of

Liang, K.-Y., Cullen, B. A. M., Grados, M. A. & Nestadt, G. Psychiatry, 157, 1291–1296.

(2000). The relationship of Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder to Phillips, K. A. (1998). Body dysmorphic disorder: Clinical aspects

possible spectrum disorders: Results from a family study. Bio- and treatment strategies. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 62(4

logical Psychiatry, 48, 287–293. Suppl A), A33–A48.

Cafri, G. & Thompson, J. K. (2007). Measurement of the muscular Phillips, K. A., Dwight, M. M. & McElroy, S. L. (1998). Efficacy

ideal. In J. K. Thompson & G. Cafri (Eds.), The muscular and safety of fluvoxamine in body dysmorphic disorder. Jour-

ideal: Psychological, social, and medical perspectives (pp. nal of Clinical Psychiatry, 59, 165–171.

107–120). Washington, DC: American Psychological Associa- Phillips, K. A. & Hollander, E. (1996). Body dysmorphic disorder.

tion. In T. A. Widige, A. J. Frances, H. A. Pincus, R. Ross, M. B.

Cohen, J., Collins, R., Darkes, J. & Gwartney, D. (2007). A league First & W. W. Davis (Eds.), DSM-IV Sourcebook, Volume 2.

of their own: Demographics, motivations and patterns of use of Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

Muscle dysmorphia

Phillips, K. A., Gunderson, C. G., Mallya, G., McElroy, S. L. & Rosen, J. C., Reiter, J. & Orosan, P. (1995). Cognitive-behavioral

Carter, W. (1998). A comparison study of body dysmorphic body image therapy for body dysmorphic disorder. Journal of

disorder and obsessive–compulsive disorder. Journal of Clini- Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 63, 263–269.

cal Psychiatry, 59, 568–575. Terry, A., Szabo, A. & Griffiths, M. D. (2004). The Exercise Ad-

Pope, C. G., Pope, H. G., Menard, W., Fay, C., Olivardia, R. & diction Inventory: A new brief screening tool. Addiction Re-

Phillips, K. A. (2005). Clinical features of muscle dysmorphia search and Theory, 12, 489–499.

among males with body dysmorphic disorder. Body image, 2, Veale, D. (2004). Body dysmorphic disorder. Postgraduate Medi-

395–400. cal Journal. 80, 67–71.

Pope, H. G., Jr., Gruber, A. J., Choi, P., Olivardia, R. & Phillips, K. Zimmerman, M. & Mattia, J. I. (1998). Body dysmorphic disorder

A. (1997). Muscle dysmorphia. An underrecognised form of in psychiatric outpatients: Recognition, prevalence, comor-

body dysmorphic disorder. Psychosomatics, 38, 548–557. bidity, demographic, and clinical correlates. Comprehensive

Pope, H. G., Jr., Katz, D. L. & Hudson, J. I. (1993). Anorexia Psychiatry, 39, 265–270.

nervosa and ‘‘reverse anorexia’’ among 108 male body-

builders. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 34, 406–409.

Journal of Behavioral Addictions

View publication stats

You might also like

- Classification System in PsychiatryDocument39 pagesClassification System in PsychiatryAbhishikta MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Denial Codes MeaningDocument6 pagesDenial Codes MeaningAlvin Chrysolyte Bilog0% (1)

- Modelul Lui Claire WeekesDocument11 pagesModelul Lui Claire WeekesDiana Alexandru-DolghiiNo ratings yet

- PTSD Women Combat VeteransDocument6 pagesPTSD Women Combat VeteransMisty JaneNo ratings yet

- Bigorexia - Bodybuilding and Muscle DysmorphiaDocument8 pagesBigorexia - Bodybuilding and Muscle DysmorphiaPatrykJanekNo ratings yet

- Patient Health QuestionnaireDocument12 pagesPatient Health QuestionnaireumibrahimNo ratings yet

- Antisocial Personality DisorderDocument6 pagesAntisocial Personality DisorderJohn Eldrin Laureano100% (1)

- Clinical Exam Handbook RCH 2013 PDFDocument25 pagesClinical Exam Handbook RCH 2013 PDFANDRE MANo ratings yet

- Physical DiscomfortDocument11 pagesPhysical DiscomfortTere NavaNo ratings yet

- Muscle DysmorphiaDocument6 pagesMuscle DysmorphiaKarla RojasNo ratings yet

- Compte Sepulveda Torrente 2018 Approximationstoanintegratedmodelof Eating Disordersand Muscle Dysmorphiaamonguniversitymalestudentsin ArgentinaDocument29 pagesCompte Sepulveda Torrente 2018 Approximationstoanintegratedmodelof Eating Disordersand Muscle Dysmorphiaamonguniversitymalestudentsin ArgentinaGaby BarrozoNo ratings yet

- Manual Therapy: Jenny Setchell, Bernadette Watson, Liz Jones, Michael GardDocument7 pagesManual Therapy: Jenny Setchell, Bernadette Watson, Liz Jones, Michael Gardanggie mosqueraNo ratings yet

- Manual Therapy: Jenny Setchell, Bernadette Watson, Liz Jones, Michael GardDocument7 pagesManual Therapy: Jenny Setchell, Bernadette Watson, Liz Jones, Michael GardKARENNo ratings yet

- Factors Influencing Muscle Dysmorphia Among Individuals Within Gym CommunitiesDocument9 pagesFactors Influencing Muscle Dysmorphia Among Individuals Within Gym Communitiesangelpode93No ratings yet

- Muscle Dysmorphia Symptomatology and Associated Psychological Features in Bodybuilders and Non-Bodybuilder Resistance Trainers - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument27 pagesMuscle Dysmorphia Symptomatology and Associated Psychological Features in Bodybuilders and Non-Bodybuilder Resistance Trainers - A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDouglas MarinNo ratings yet

- TCA - Compte y DuthuDocument4 pagesTCA - Compte y DuthuGaby BarrozoNo ratings yet

- 2012 - ACT Y FAP en Trastorno Dismórfico (Instrumentos, Referencias, Otras Aplicaciones... )Document9 pages2012 - ACT Y FAP en Trastorno Dismórfico (Instrumentos, Referencias, Otras Aplicaciones... )domingo jesus de la rosa diazNo ratings yet

- Topic 9Document43 pagesTopic 9Muhd syazaniNo ratings yet

- Health Benefits of ExerciseDocument16 pagesHealth Benefits of Exerciselalala lalalalNo ratings yet

- Ni Hms 862712Document23 pagesNi Hms 862712enfermeironilson6321No ratings yet

- Weight Management Practices of Bachelor of Physical Education StudentsDocument32 pagesWeight Management Practices of Bachelor of Physical Education StudentsRalph Rexor Macarayan BantuganNo ratings yet

- Aarr - Jul.2017Document27 pagesAarr - Jul.2017hidememeNo ratings yet

- Physical Therapy After Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review of Treatments Focused On ParticipationDocument10 pagesPhysical Therapy After Spinal Cord Injury: A Systematic Review of Treatments Focused On ParticipationInaauliahanNo ratings yet

- Acceptance and Commitment Therapy For Women Diagnosed With Binge EatingDocument12 pagesAcceptance and Commitment Therapy For Women Diagnosed With Binge EatingPamela MaercovichNo ratings yet

- DismorfiaDocument11 pagesDismorfiaKarla RojasNo ratings yet

- Compte Et Al., 2022 Psychometric Evaluation of The Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory (MDDI) Among Gender-Expansive PeopleDocument11 pagesCompte Et Al., 2022 Psychometric Evaluation of The Muscle Dysmorphic Disorder Inventory (MDDI) Among Gender-Expansive PeopleEmilio J. CompteNo ratings yet

- Exercise Dependence and Muscle Dysmorphia in NoviceDocument5 pagesExercise Dependence and Muscle Dysmorphia in Noviceamandarhp12No ratings yet

- 02 - Obesity Is A Disease Examining The Self-Regulatory Impact of This Public Health Message - 2014Document6 pages02 - Obesity Is A Disease Examining The Self-Regulatory Impact of This Public Health Message - 2014damlaycinNo ratings yet

- Weight Stigma Experiences and Self-Exclusion From Sport and Exercise Settings Among People With ObesityDocument18 pagesWeight Stigma Experiences and Self-Exclusion From Sport and Exercise Settings Among People With Obesitypablo.s4672No ratings yet

- Physical Exercise and Morbid Obesity: A Systematic ReviewDocument7 pagesPhysical Exercise and Morbid Obesity: A Systematic ReviewTito AlhoNo ratings yet

- Consequences of Objective Self-Awareness During Exercise: Jessica E Cornick and Jim BlascovichDocument9 pagesConsequences of Objective Self-Awareness During Exercise: Jessica E Cornick and Jim Blascovichإيمان سبيكةNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis To Function: Classification For Children and YouthsDocument8 pagesDiagnosis To Function: Classification For Children and YouthsVe SaNo ratings yet

- Body Dissatisfaction, Addiction To Exercise and Risk Behaviour For Eating Disorders Among Exercise PractitionersDocument9 pagesBody Dissatisfaction, Addiction To Exercise and Risk Behaviour For Eating Disorders Among Exercise PractitionersArizka KhoirunnisaNo ratings yet

- Tugas Kelompok 1Document17 pagesTugas Kelompok 1FrederickSuryaNo ratings yet

- Muscle Dysmorphia Disorder: (MDD or Vigorexy)Document4 pagesMuscle Dysmorphia Disorder: (MDD or Vigorexy)Kate20No ratings yet

- The Body Image Psychological Inflexibility Scale DevelopmentDocument8 pagesThe Body Image Psychological Inflexibility Scale DevelopmentAna Gómez EstebanNo ratings yet

- Exercise Dependence, Social Physique Anxiety, and Social Support in Experienced and Inexperienced Bodybuilders and WeightliftersDocument5 pagesExercise Dependence, Social Physique Anxiety, and Social Support in Experienced and Inexperienced Bodybuilders and WeightliftersArthur CamargoNo ratings yet

- Physical Self-Concept and Its Relationship To Exercise Dependence Symptoms in Young Regular Physical ExercisersDocument6 pagesPhysical Self-Concept and Its Relationship To Exercise Dependence Symptoms in Young Regular Physical ExercisersBarney MooreNo ratings yet

- ThethreemusketeersprepDocument14 pagesThethreemusketeersprepapi-439630196No ratings yet

- Ivan 2Document5 pagesIvan 2Kamal Singh BhandariNo ratings yet

- Danridgeetal 2014 PTstudentsandmentalhealthptsDocument8 pagesDanridgeetal 2014 PTstudentsandmentalhealthptsDoctor MemiNo ratings yet

- Running Head: Annotated Bibliography 1Document10 pagesRunning Head: Annotated Bibliography 1api-242764271No ratings yet

- Research Team DraftDocument8 pagesResearch Team DraftJanine Tricia Bitoon AgoteNo ratings yet

- Wolrich2011 Article BodyDysmorphicDisorderAndItsSiDocument10 pagesWolrich2011 Article BodyDysmorphicDisorderAndItsSiDanya KatsNo ratings yet

- Weight Stigma and Health Behaviors: Evidence From The Eating in America StudyDocument11 pagesWeight Stigma and Health Behaviors: Evidence From The Eating in America StudypedroNo ratings yet

- A Cross-Sectional Study of Awareness of Physical Activity Associations With Personal, Behavioral and Psychosocial FactorsDocument9 pagesA Cross-Sectional Study of Awareness of Physical Activity Associations With Personal, Behavioral and Psychosocial FactorsTanushree BiswasNo ratings yet

- Amy FordDocument18 pagesAmy FordJaneNo ratings yet

- KANALEY-2022-EXERCISE & PA in T2D - ACSM Consensus StatementDocument37 pagesKANALEY-2022-EXERCISE & PA in T2D - ACSM Consensus StatementJoel PuenteNo ratings yet

- Research Paper 3Document8 pagesResearch Paper 3ljtimpersNo ratings yet

- Rosen Et Al, 1995Document8 pagesRosen Et Al, 1995DiegoNo ratings yet

- 2 Motorik RinganDocument9 pages2 Motorik RinganlielhiannaNo ratings yet

- Obesity and Internalized Weight StigmaDocument14 pagesObesity and Internalized Weight StigmaPaola Munda GazzanigaNo ratings yet

- Case ReportDocument9 pagesCase ReportStephany Granados GonzalezNo ratings yet

- Fall Prevention in Dementia Patients - NSG 464 - Abigail PowersDocument10 pagesFall Prevention in Dementia Patients - NSG 464 - Abigail Powersapi-591508557No ratings yet

- Assessment Tools in ObesityDocument39 pagesAssessment Tools in ObesityPatricio GGNo ratings yet

- Nursing TheoryDocument11 pagesNursing TheoryJenny SembranoNo ratings yet

- Las Dietas No Son La RespuestaDocument15 pagesLas Dietas No Son La RespuestaKarla Salgado CallejasNo ratings yet

- Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med-2018-Ruegsegger-A029694Document16 pagesCold Spring Harb Perspect Med-2018-Ruegsegger-A029694maulana adiNo ratings yet

- Fpsyt 12 751550Document9 pagesFpsyt 12 751550tatiana CastañedaNo ratings yet

- PAPER 2 SEMANA 1 2017-The Limits of Exercise Physiology - From Performance To HealthDocument12 pagesPAPER 2 SEMANA 1 2017-The Limits of Exercise Physiology - From Performance To Healthsebakinesico-1No ratings yet

- Definitions - Health, Fitness, and Physical Activity-Presidents Council-2000Document12 pagesDefinitions - Health, Fitness, and Physical Activity-Presidents Council-2000Paula Melissa Castillo PradaNo ratings yet

- International Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand Diets and Body CompositionDocument19 pagesInternational Society of Sports Nutrition Position Stand Diets and Body CompositionLuis Ricardo Hernandez GarciaNo ratings yet

- Bs TemperamentDocument12 pagesBs TemperamentFrancisco TNo ratings yet

- Obesity Treatment, Prevention and Management: Ajeet JaiswalDocument38 pagesObesity Treatment, Prevention and Management: Ajeet JaiswalVisioning SolitudeNo ratings yet

- Study of Physical Fitness Index Using Modified Harvard Step Test in Relation With Body Mass Index in Physiotherapy StudentsDocument4 pagesStudy of Physical Fitness Index Using Modified Harvard Step Test in Relation With Body Mass Index in Physiotherapy StudentsUswatun HasanahNo ratings yet

- Dieta Kuppens 2019 PDFDocument37 pagesDieta Kuppens 2019 PDFAlexandra HuhNo ratings yet

- Summary, Analysis & Review of Sylvia Tara’s The Secret Life of FatFrom EverandSummary, Analysis & Review of Sylvia Tara’s The Secret Life of FatNo ratings yet

- Ayushi Soni PeriostitisDocument24 pagesAyushi Soni Periostitisfyt2886No ratings yet

- Student Guide: SourceDocument82 pagesStudent Guide: Sourcewaraney palitNo ratings yet

- Common Mental Health Problems: BMJ (Online) May 2005Document5 pagesCommon Mental Health Problems: BMJ (Online) May 2005Saralys MendietaNo ratings yet

- Mazda-Allegro-Mazda-Protege 2002 EN US Manual de Taller Airbag Cinturon de Seguridad 0e4ac4b1bdDocument72 pagesMazda-Allegro-Mazda-Protege 2002 EN US Manual de Taller Airbag Cinturon de Seguridad 0e4ac4b1bdJoséAlbertoPiñangoMonterreyNo ratings yet

- Lesson19 PDFDocument16 pagesLesson19 PDFAmzat AbbasNo ratings yet

- Summary X Ray MachineDocument3 pagesSummary X Ray MachineIndri SuciNo ratings yet

- 4753-Article Text-31653-2-10-20221130Document9 pages4753-Article Text-31653-2-10-20221130ariniyulfa endrianiNo ratings yet

- Anxiety and Depression in Young PeopleDocument11 pagesAnxiety and Depression in Young PeopleKyle SaylonNo ratings yet

- Sample Maxicare+EReady+Advance - HMOADocument15 pagesSample Maxicare+EReady+Advance - HMOAbbyshe0% (1)

- Psychiatric Clerking SheetDocument7 pagesPsychiatric Clerking Sheet0045 NAZIRA ZATY BINTI ABD KARIMNo ratings yet

- Anonymization of Electronic Medical Records To Support Clinical Analysis (PDFDrive)Document86 pagesAnonymization of Electronic Medical Records To Support Clinical Analysis (PDFDrive)lauracdqNo ratings yet

- Referralsystem 161202080450Document21 pagesReferralsystem 161202080450DRx Sonali Tarei100% (1)

- OS Automotive Electromech L4Document76 pagesOS Automotive Electromech L4Aida Mohammed80% (5)

- Pmlsp1 - Intro and HistoryDocument4 pagesPmlsp1 - Intro and HistoryJm AshiiNo ratings yet

- Temporomandibular Disorders - A Review of Current Concepts inDocument24 pagesTemporomandibular Disorders - A Review of Current Concepts inAlba Letícia MedeirosNo ratings yet

- 2008 Nissan Teana J32 Service Manual-AVDocument673 pages2008 Nissan Teana J32 Service Manual-AVMrihex100% (2)

- Personal Notes While at McLeanDocument12 pagesPersonal Notes While at McLeanmcleanhospitalNo ratings yet

- Estatus Epileptico de Nuevo Inicio (NORSE)Document8 pagesEstatus Epileptico de Nuevo Inicio (NORSE)juanutNo ratings yet

- Holden Caulfield DiagnosisDocument5 pagesHolden Caulfield Diagnosisscrmaverick132654100% (1)

- BAH Test Report Orientation V.2.pagesDocument7 pagesBAH Test Report Orientation V.2.pagesIsaac FornarolaNo ratings yet

- PTSD EssayDocument5 pagesPTSD Essayapi-337353986No ratings yet

- Nursing Diagnosis Group 2Document21 pagesNursing Diagnosis Group 2Harfiana Syahrayni100% (1)

- Resolving Obsessive Compulsive Disorder OCD Once and For AllDocument2 pagesResolving Obsessive Compulsive Disorder OCD Once and For AllAngelica CiubalNo ratings yet