Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Alves, Milberg, & Walsh, 2012 - Exploring Lean Construction Practice, Research, and Education

Uploaded by

apostolos thomasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Alves, Milberg, & Walsh, 2012 - Exploring Lean Construction Practice, Research, and Education

Uploaded by

apostolos thomasCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/235299738

Exploring lean construction practice, research, and education

Article in Engineering Construction & Architectural Management · August 2012

DOI: 10.1108/09699981211259595

CITATIONS READS

52 328

3 authors, including:

Thais Alves Ken Walsh

San Diego State University University of California, Irvine

68 PUBLICATIONS 456 CITATIONS 94 PUBLICATIONS 940 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

CII RT-308 Achieving Zero Rework through Effective Supplier Quality Practices View project

Dynamics of project-driven systems: A production model for repetitive processes in construction View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Thais Alves on 25 February 2019.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

435

EXPLORING LEAN CONSTRUCTION

PRACTICE, RESEARCH, AND EDUCATION

Thaís da C. L. Alves1, Colin Milberg2, Kenneth D. Walsh3

ABSTRACT

Lean Production has been studied for over 20 years, and for many the term is still ill-

defined. Our first hypothesis suggests that there are many meanings for Lean when

applied to Construction. Our second hypothesis suggests that Lean Construction

started not from industry but from a mix of academics and consultants (with strong

links to academia) working to translate Lean concepts to construction. We believe that

both play a major role in bridging the gap between the theories related to Lean

Construction and their implementation. Finally, we have encountered examples of

companies and professionals who are eager to benefit from the alleged benefits of

Lean Production but few are willing to spend the time and effort necessary to learn it.

Our third hypothesis suggests that without a sustained effort to engage people in

meaningful learning experiences Lean Construction may be viewed as a fad in the

construction industry. We searched the literature and looked for cases with different

approaches used to disseminate Lean Production and have found evidence that

supports the hypotheses proposed. The paper aims to discuss how lean production

transitioned to construction and what researchers and practitioners might do to sustain

learning and promote change throughout the industry.

KEY WORDS

Lean implementation, Education, Change

INTRODUCTION

Lean Production (LP) concepts, principles, and tools have been studied by academics

for over 20 years (e.g., Womack et al. 1990). Nonetheless, for many the term Lean

Production is still considered an ill-defined concept which needs further exploration

and agreement in academic as well as in professional settings (Hines et al. 2004,

Jorgensen and Emmitt 2008, Pettersen 2009). The application of LP in construction is

almost as old, as the term ‗Lean Construction‘ (LC) first appeared in 1992 (Koskela

1992). However, only in the past 5-6 years has it gained widespread momentum with

a larger group of construction companies, owners, industry associations, and public

institutions interested in becoming acquainted with, and proficient in, Lean

implementation.

In California, for instance, a few major events may have boosted the popularity of

LC amongst construction companies namely: the decision by Sutter Health to change

1

Assistant Professor, J.R. Filanc Construction Engineering and Management Program, Department of

Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering, San Diego State University (SDSU), San Diego,

CA, 92182-1324, USA, Phone +1 619/594-8289, talves@mail.sdsu.edu

2

Assistant Professor, J.R. Filanc Construction Engineering and Management Program, Department of

Civil, Construction, and Environmental Engineering, SDSU, cmilberg@mail.sdsu.edu

3

Professor, J.R. Filanc Construction Engineering and Management Program, Department of Civil,

Construction, and Environmental Engineering, SDSU, kwalsh@mail.sdsu.edu

People Culture and Change

436 Thaís da C. L. Alves, Colin Milberg, and Kenneth D. Walsh

the way its capital projects were contracted, designed, and built (Lichtig 2005); the

creation of the Project-Production Sytems Laboratory (P2SL) at UC Berkeley in

2005; the proliferation of Lean Construction Institute (LCI) chapters, starting with the

Northern California chapter; and the large state-funded ‗California Prison Health Care

Receivership‘ Coop-etition, which started around 2008 and brought together

competitors and collaborators to work on the design and construction of seven million

square feet of correctional healthcare facilities (CPRINC 2010). Currently in

California, a number of requests for proposals (RFPs) from public and private owners

have incorporated some sort of requirement related to LC use (e.g., Integrated Project

Delivery (IPD), Last Planner™, pull planning, use of Lean principles).

Recently, large United States industry associations (e.g., AGC, AIA) and legal

experts have also joined the LC community, which in the beginning was largely

formed by academics, ostensibly to aid the change towards a more efficient industry

based on the tenets of LP. Nationwide in the U.S., contracts are changing to

accommodate the needs of IPD teams, and the request for explicit collaboration

between project participants is now part of these contracts, e.g., AIA IPD family of

contracts (AIA 2010).

By now in the construction industry, as in other sectors, a large body of ‗Lean‘

literature and implementation examples abound (e.g., www.iglc.net), but some

authors still criticize LC as a discipline due to the lack of structured research findings

and critical discussion based on publication of papers in peer-reviewed journals

(Thomas et al. 2004, Jorgensen and Emmitt 2008). Criticisms about the LP system in

its original form, i.e., the Toyota Production System (Ohno 1988, Shingo 1989), can

also be found in the literature and these help us understand what has to be in place for

this system to work (Berggren 1993, Lilrank 1994, Scott et al. 2001). Some authors

have highlighted that to make this system work some preconditions have to be met:

design of products for easy manufacture; careful selection and management of

workers and suppliers; fast-paced work and close monitoring and adherence to

standards, amongst others (e.g., Berggren 1993, Lilrank 1994).

In this paper, we focus on how LP has evolved in the construction industry and

what implications that evolution brings to its widespread dissemination in this

industry through academic and professional communities of practice located all over

the world.

RESEARCH METHOD AND GOALS

This paper is based on three hypotheses, related to the current understanding of LC

and its development and dissemination in the industry. To some extent, these

impressions were formed via interactions with companies attempting to deploy LC.

The authors gathered evidence from the literature on the topic and from current

developments related to the advance and implementation of Lean practices in the

construction industry. We searched the literature and looked for cases in academic

and professional settings for different approaches used to disseminate Lean. The paper

aims to discuss important aspects related to Lean Construction learning and training

programs, in order to create a basis for further research into sustainable approaches

for teaching Lean Construction in different settings within the construction industry.

Proceedings IGLC-18, July 2010, Technion, Haifa, Israel

Exploring Lean Construction Practice, Research, and Education 437

DISCUSSION OF HYPHOTESES

HYPOTHESIS 1

H1: ―There are many meanings (whether denoted or connoted) for Lean when

applied to Construction.‖

Pettersen (2009) argues that there is no consensus on a definition of Lean

Production (LP), which causes confusion on both theoretical and practical levels. The

confusion at the practical level causes more problems because organizations try to

implement the LP concepts without uniformity in terms of how to interpret and

implement. ―Formulating a definition that captures all the dimensions of lean is a

formidable challenge‖ (Pettersen 2009, p.136). In the LC domain Jorgensen and

Emmitt (2008, 392) argue that ―a coherent philosophy for lean construction has not

yet been developed‖.

One of the reasons for the lack of a precise definition for what a Lean system

entails is the lack of definition of LP where it all started. Despite the ever growing

literature on the topic, Lillrank (1995, p.972-973) highlights that ―The Japanese have

not been very articulate about the reasons for their success. (…) There was no great

master plan up front and no blueprints that could have been studied. Therefore, the

Japanese experience was wide open for various explanations and interpretations.‖

Womack and Jones (2003) have not claimed that Lean Thinking (LT) is a theory.

The authors tried to draw conclusions from the work they presented in The Machine

that Changed the World (Womack et al. 1990) and the results obtained by the

organizations that they deemed Lean.

Koskela (2004) suggested that the principles presented by Womack and Jones

(2003) are highly compressed and that they may be detrimental to the understanding

of LP as a whole, as many elements may be missing in the explanation of the five LT

principles. Womack et al. (1990) and Womack and Jones (2003) provided an

unprecedented basis for the dissemination of Japanese organizational practices, which

had not been achieved by other pioneers on the topic. These books popularized LP

and made the Toyota Production System (TPS) more palatable to broad audiences.

However, Koskela (2004) stressed that Womack and Jones‘ (2003) Lean Thinking

book lacks the discussion of explicit concepts that would provide the foundations of

LT as an offspring of the TPS as discussed by Ohno (1988) and Shingo (1989).

Even though many do not agree on possible commonalities in the implementation

of LP, according to Olivella et al. (2008) there is a group of work organization

practices that are related to the implementation of lean production, namely:

standardization, discipline and control; continuing training and learning; team-based

organization; participation and empowerment; multiskilling and adaptability; common

values, compensation and rewards to support LP. These practices are usually selected

based on the social and organizational background of the company and adapted to suit

its context. However, often times, the implementation of isolated practices fail

because they do not belong to a comprehensive plan that addresses both the social and

the technical parts of the organization (Lathin and Mitchell 2001).

Much has been said about the contextual roots of LP and its origins in the mass

production environment marked by high volumes of repetitive tasks performed in

permanent locations and organizations (Berggren 1993, Lillrank 1994, 1995).

Therefore, the application of LP in a project-based environment such as construction,

People Culture and Change

438 Thaís da C. L. Alves, Colin Milberg, and Kenneth D. Walsh

with temporary teams allocated to geographically diverse projects and clients, and

highly worker-intensive and dependent tasks, requires careful understanding of its

tenets and adaptation to the peculiarities of the sector.

Over the years, LC was often understood by many across the globe as a set of

tools and practices aimed at reducing waste in construction projects and the

implementation of the Last Planner System of Production Control™ (LPS™), as this

system emulates many concepts, principles and tools found in the literature on TPS

(i.e., Ohno 1988, Shingo 1989): pull planning, analysis of the root causes of problems,

and definition of sound assignments, to name just a few.

A search on the iglc.net website reveals a repeated focus of early IGLC papers on

waste identification and elimination, amongst other topics. As Ohno (1988) and

Shingo (1989) reinforced the need to identify and banish waste in their classic books,

the construction industry started the LC development by understanding what waste

meant for the industry, how it was created, and how it could be eliminated. The

understanding of LC as a synonym of waste elimination can still be found in papers

submitted to the IGLC, and in discussions in professional forums, by academics and

practitioners who are in the initial stages of LC implementation (e.g., Forsberg and

Saukkoriipi 2007, Ramaswamy and Kalidindi 2009).

LPS™ as starting point for LC implementation could be evidenced by the

predominance of papers on project management in IGLC conferences, such as the

ones analyzed by Alves and Tsao (2007). The implementation of the LPS™ is seen by

many as the door to start LC implementation as it promotes stability and learning

through systematic planning and control of weekly assignments as discussed by

Ballard and Howell (1998).

The focus on waste elimination and production planning and control has placed

much attention on the transformation and flow aspects of the tasks performed by an

organization, but missed the third essential component to managing production

systems: value (Koskela 2000). According to Hines et al. (2004, p.995): ―A critical

point in the lean thinking is the focus on value. Often however, value creation is seen

as equal to cost reduction. This represents a common yet critical shortcoming of the

understanding of lean.‖

Different countries have understood LC from various perspectives. According to

Emmitt et al. (2005), for instance, LC was originally interpreted and applied in

Denmark with a very narrow focus which comprised the use of logistics concepts

applied to the flows of materials and activities and the Last Planner System™, and

apparently some understanding of Lean as partnering.

The abundance of LP and LC meanings calls for more research to explain what

their constituent concepts represent and search for more uniform definitions to shape a

common understanding throughout the industry. Furthermore, the practical execution

impacts of this condition require additional study. This leads us to the second

hypothesis discussed in this paper.

HYPOTHESIS 2

H2: ―Lean Construction, in contrast to Lean Production, started not from industry

but from a mix of academics and consultants (with strong links to academia) working

to translate Lean concepts to the construction industry. Therefore, we believe that

academics play a major role in bridging the gap between the theories related to Lean

Proceedings IGLC-18, July 2010, Technion, Haifa, Israel

Exploring Lean Construction Practice, Research, and Education 439

Construction and their field implementation, as they work as translators of the

concepts originating in the manufacturing industry.‖

The first account on the potential use of LP in construction can be found in the

seminal work by Koskela (1992) and his attempt to come up with a theory of

production management. The first IGLC conference hosted in Espoo, Finland in 1993

comprised a handful of papers, a very different scenario when compared to recent

IGLC conferences which have added an ‗industry day‘ before the main event and

welcome papers from both academics and professionals working to advance LC

(IGLC 2010).

The IGLC has played a central role in the dissemination of LC in the construction

industry due to the diversity of views presented about LC and its implementation in

different parts of the world. The group has an unwritten policy of inclusion which

allows academics and practitioners in different stages of their LC journey to join the

conversation and share their ideas by publishing papers made available online to the

community.

In addition to the role played by the IGLC group, the Lean Construction Institute

(LCI) has bridged the gap between academia and industry by promoting LC to

industry practitioners through the development of research projects and the promotion

of events to disseminate and consolidate LC practices. LCI represents the LC

community to the industry and for many it is the entry door to the global LC network.

From its inception in 1997, LCI has made its knowledge base available online, and

immensely contributed to the dissemination and support of LC in different regions of

the United States and abroad through international LCI chapters (LCI 2010).

However, despite the broad capillarity both organizations have in academic and

professional settings, and their fundamental commitment to being self-sustained and

disseminating LC free of charge, there is criticism in terms of how LC concepts,

principles, and tools have been disseminated. Jorgensen and Emmitt (2008) criticize

the lack of detail presented in publications regarding Japanese management practices,

and the lack of description on data collection and validation. They also criticize IGLC

proceedings for being biased towards describing positive improvements, being self-

referential citing mainly the IGLC literature and a handful of papers on

construction/production management, and finally lacking criticism and being too slow

in promoting a critical and informed debate especially in peer reviewed journals.

While many directions could be pursued from this discussion, the point here is

only to call attention to the importance of academics in translating and disseminating

LC. Koskela (2004) stresses the need for adaptation when LP principles are applied to

one-of-a-kind production with temporary location and organization, e.g., construction.

Management principles are context-specific and depend on culture, local market and

business conditions, level of education, incentive structures, amongst others (Lillrank

1995). In its original and more orthodox form, LP also has limitations, e.g., the

availability of workers capable and willing to work long hours, the stress related to

lower levels of inventory, location of suppliers, or design of models that share

parts/plants and are easy to assemble (Berggren 1993).

While many in the industry have genuine interest in implementing LC in their

organizations, few have the time and the interest to read detailed accounts of LP and

LC implementation, and consequently often rely on academics and consultants for

that. Lillrank (1995) contends that organizational innovations may take years if not

People Culture and Change

440 Thaís da C. L. Alves, Colin Milberg, and Kenneth D. Walsh

decades to be transferred (i.e., study of successful practices and learning related to

their implementation) from their original context to other applications. Lillrank (1995)

uses the ―high-voltage electric transmission analogy‖ as a metaphor to explain how

ideas travel through different contexts. In the case of electricity, the electric current is

set to higher voltages to overcome resistance in the cables and reach its destination;

when it reaches its destination the electric current is switched to lower and usable

voltages. Lillrank (1995) mentions that the transfer of ideas travel through an ‗idea

line‘ in which losses will also occur based on the geographical, cultural, mental, and

historic differences between the start and end points. In order to reduce the losses,

ideas are abstracted away from their original context and packaged in a format that

allows them to travel through the ‗idea line‘. By the time the ideas reach their

destination they have to be repackaged, triggering multiple cycles of learning related

to interpretation and adaptation to local conditions.

One example of how these ideas travel and how they get adapted to specific

contexts is the slow, but continuous, evolution of LC ideas in the construction

industry as pointed out by Ballard (2008, 18): ―the Lean Project Delivery System is

not a mere creature of the imagination, but rather an emerging practice fed by

multiple streams of experimentation.‖ Ballard goes on to acknowledge that there are

multiple companies experimenting with LC and multiple research labs, in addition to

the IGLC community, working to collectively advance LC.

Finally, Koskela and Rooke (2009, p.339) also point out that the main question to

be answered in management research is whatever is being done, ―does it help improve

performance?‖ This leads to the third hypothesis, which points out the need for

continuous learning to sustain improvement and promote change in the construction

industry.

HYPOTHESIS 3

H3: ―Without a sustained effort to engage people in meaningful learning experiences

which mix instruction, exchange of ideas and meanings, and guided practice, Lean

Construction may be viewed as a fad in the construction industry.‖

In interacting with the industry we have encountered many examples of

companies and individuals who are eager to learn about Lean Thinking, but few who

are willing to spend the time and effort necessary to learn the basis of what the

literature presents as Lean Thinking and its applications. A number of short seminars

and meetings are offered by different organizations in order to respond to requests

from professionals trying to learn about the topic quickly but little has been done in

the industry to promote sustained and continuous learning. We believe that many

companies in the construction industry have currently embraced systems and tools

(e.g., LPS™, pull planning, kanban, A3) but not necessarily their basic concepts. This

is a very similar environment to the one described by Cole (1999) about the quality

movement in U.S. in its early years. He points out that quality management was

perceived by U.S. companies as the implementation of tools and isolated practices,

and it almost became an unsuccessful initiative (a fad), before organizations could

consider quality management as an integral part of their businesses.

Lillrank, 1994 (p.427) highlights that ―Lean production requires a set of soft

enablers, that is, social and organizational conditions to match the inherent fragility of

the just-in-time-system. Working under lean management is difficult in two ways: it

Proceedings IGLC-18, July 2010, Technion, Haifa, Israel

Exploring Lean Construction Practice, Research, and Education 441

requires fast-paced work closely following standard operating procedures (SOP) and a

continuous vigilance to improve SOPs.‖ At Toyota, the combination of problem-

solving and kaizen on the shop floor is a priority and consists of a methodical process

described by many (Ohno 1988; Shingo 1989; Berggren 1993). The development and

use of standards and documentation of best practices allow deviations to be quickly

identified and acted upon, serving as a basis for organizational learning. In the LP

system, workers have to work hard to meet the high standards expected from them,

and managers have to work even harder than they would in some other organizations

to keep the system running (Berggren 1993).

The fast-paced environment of LP as applied in the manufacturing industry has

yet to be a reality in construction. In fact, this may never happen in an industry whose

pace is largely dictated by human rather than machine work. However, the message is

clear: social and organizational conditions, in addition to strong leadership and

management leading by example, have to exist for a system based on LP to work.

Hirota et al. (1999) investigated potential ways to disseminate LC in organizations

using a more systematic method and came up with three approaches: the use of a tool

to negotiate meanings, development of organizational learning, and the use of action

learning. The ‗concept mapping‘ tool was used to negotiate the meanings of different

LC-related concepts and principles and their relationships in a group of project

managers learning about LC. The goal of this tool was to bridge the gap between the

participants thought and speech, and make the understanding of the theory explicit

during discussions about how the LC theory and its components interrelate. The

second approach investigated was ‗organizational learning‘ to engage the

organizations in the development of a collective learning process and collective

competencies to promote the adoption of LC and its implementation. Finally, the

third approach was the use of ‗action learning‘, in which regular meetings were held

with a group of participants steered by a set advisor who questioned participants about

their managerial problems and required participants to commit to bringing a solution

to be discussed with the group.

An approach somewhat similar to action learning meetings, which has been

gaining popularity amongst the LC community, is the study-action team™ (Lean

Project Consulting 2010). In this setting, participants are tasked with reading a book

and meeting to discuss the book and reflect on how the book‘s teachings apply to their

environment. However, Scott et al. (2001) faced some problems when trying to use

action learning in a manufacturing company using LP practices. They found that some

of the workers who participated in the action learning sets viewed 1-hour per week

spent on these activities as inactive work, and as activities that ‗legitimized non-work‘

in a just-in-time environment in which people were rewarded for being ‗visibly active

urgent, loud, and hands-on in the factory‘. In this case, the manufacturing company

workers may have misinterpreted what LP means, but does that remind us of the

construction environment and how LC may be perceived by some practitioners?

If activities such as action learning sets and study-action teams™ are not viewed

as productive, they do not encourage participation and collective growth. Therefore,

we suggest that planning sessions and regular meetings, along the lines of the LPS™,

already in place at the organization be used as the starting point for the organizational

learning process. In these settings, LC concepts and principles can be used as the basis

People Culture and Change

442 Thaís da C. L. Alves, Colin Milberg, and Kenneth D. Walsh

for discussion and explanation of the production phenomena and promote learning

amongst project participants.

Another important point concerning LC learning is the need to ‗unlearn‘.

According to McGill and Slocum (1993, p.78): ―organizational learning is about

more than simply acquiring new knowledge and insights; it requires managers to

unlearn old practices that have outlived their usefulness and discard ways of

processing experiences that have worked in the past. Unlearning makes way for new

experiences and new ways of experiencing. It is the necessary precursor to learning.‖

This quote illustrates much of what has been happening in the construction industry

for years as construction management researchers have called for a reform in the way

the industry operates and for a theory of production management (Koskela and

Howell 2002).

McGill and Slocum (1993, p.76) also suggest that the learning organization

promotes continuous experimentation and the pursuit of continuous improvement, and

rewards behaviors that reinforce this pattern: ―a learning organization has a culture of

value set that promotes learning. A learning culture is characterized by its clear and

consistent (1) openness to experience; (2) encouragement of responsible risk taking;

and willingness to acknowledge failures to learn from them. (…) Groups engage in

active dialogue and conversations, not discussions. These conversations are

reflective, as opposed to argumentative, and they are guided by leaders who facilitate

the building of strong relationships among key stakeholder groups.‖

CONCLUSIONS

This paper discussed hypotheses related to the evolution of LC in the industry with

the aim of forming a basis for an informed discussion on how to promote sustained

and informed learning in construction.

The literature review supports H1. The basis of LP is somewhat undefined, even

at its source at Toyota, and most books on the topic do not define LP is a theory. That

has not been detrimental to its growing popularity. However, in the process of

abstracting ideas away from their original context, packaging them for transfer and

later for implementation, biases are introduced. Without a foundational definition to

use as a touchstone, it is difficult to assure that its dissemination has kept its core

concepts. The lack of agreement in terms of what LP means may have an impact on

the way LC practices are understood and disseminated across the industry. Thus, a

new hypothesis for future research emerges: ―the abundance of meanings related to

LP impacts the way academic courses, research, and professional training programs

about Lean Construction are developed.

A review of how LP slowly transitioned to construction starting from the early

1990s supports H2. Papers and information available in the IGLC (2010) and LCI

(2010) websites suggest that academics were, and still are, very much involved in LP

dissemination in the construction industry.

H3 builds on the previous two hypotheses. The promotion of meaningful learning

experiences and informed discussions about LC concepts, principles, and tools should

contribute to the advancement of LC in a sustainable way and promote uniformity in

the way concepts are learned across the industry. In many ways the construction

industry has to both get rid of old habits and learn to work differently. Sharing

experiences in communities such as the IGLC, EGLC, LCI, and many research labs

Proceedings IGLC-18, July 2010, Technion, Haifa, Israel

Exploring Lean Construction Practice, Research, and Education 443

helps industry professionals to engage in new experiences, share their successes and

failures, and make the implementation of LC scalable in a sustainable fashion. In

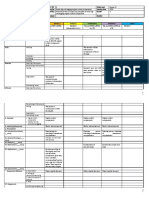

conclusion, Figure 1 summarizes this view of the journey starting with the translation

of Lean Production to Lean Construction by academics, followed by the translation

and implementation in small groups within the industry, and finally broad

implementation across the industry

Translating and Scaling sustainable

Making sense of

LP applied to implementing in implementation within

Construction small groups companies in the industry

H1 H2 H3

Lean Lean

Production Construction

Small group, mostly Communities of Industry-wide implementation

academics, early years practice (IGLC, LCI, (communities of practice,

EGLC, Research Labs, associations, government)

(IGLC)

individual companies)

Figure 1: Relationship between the hypotheses presented

REFERENCES

Alves, T.C.L. and Tsao, C.C.Y. (2007) ―Lean Construction 2000-2006.‖ Lean

Construction Journal, v.3, n.1, 46-70

AIA - The American Institute of Architects (2010). Integrated Project Delivery (IPD)

Family. http://www.aia.org/contractdocs/AIAS076706

Ballard, G. and Howell, G. (1998). ―Shielding Production: Essential Step in

Production Control.‖ J. of Constr. Engrg. and Mgmt., 124(1), 11-17

Ballard, G. (2008). ―The Lean Project Delivery System: An Update.‖ Lean

Construction Journal, 1-19

Berggren, C. (1993). ―Lean Production: the End of History.‖ Work Employment

Society. V.7, n.2, 163-188

Cole, R.E. (1999) Managing Quality Fads: How American Business Learned to Play

the Quality Game. ASQ, Oxford University Press: New York, 284pp.

CPRINC(2010). California Prison Health Care Services.

http://www.cprinc.org/project_const.aspx

Emmitt, S., Sander, D., and Christoffersen, A.K. (2005) ―The Value Universe:

Defining a Value Based Approach to Lean Construction.‖ Proceedings IGLC-13,

Sydney, Australia, 57-64

Forsberg, A. and Saukkoriipi, L. (2007) ―Measurement of Waste and Productivity in

Relation to Lean Thinking.‖ Proceedings IGLC-15, East Lansing, MI, 67-76

Hines, P., Holweg, M., and Rich, N. (2004) ―Learning to Evolve.‖ International

Journal of Operations and Production Management, v. 24, n.10, 994-1011

Hirota, E.H., Lantelme, E.M.V., and Formoso, C.T. (1999). ―Learning how to Learn

Lean Construction Concepts and Principles.‖ Proceedings IGLC-7, Berkeley, CA,

411-422

International Group for Lean Construction – IGLC (2010) www.iglc.net

People Culture and Change

444 Thaís da C. L. Alves, Colin Milberg, and Kenneth D. Walsh

Jorgensen, B. and Emmitt, S. (2008). ―Lost in transition: the Transfer of Lean

Manufacturing to Construction.‖ Engrg, Constr., and Arch. Mgmt., 15(4) 383-398

Koskela, L. (1992). Application of the New Production Philosophy to Construction.

Stanford University, CIFE Technical Report # 72, 87 pp.

Koskela, L. (2000). ―An Exploration Towards a Production Theory and its

Application to Construction‖. Ph.D. Dissertation, VTT Publications 408. VTT:

Espoo, Finland, 296 pp.

Koskela, L. (2004) ―Moving-on – beyond Lean Thinking.‖ Lean Construction

Journal, Lean Construction Institute, v.1, n.1, 24-37

Koskela, L. and Howell, G., (2002). ―The Underlying Theory of Project Management

is Obsolete.‖ Proceedings of the PMI of the PMI Research Conference, 293-302.

Koskela, L. and Rooke, J. (2009) ―What Triggers Management Innovation?‖

Proceedings IGLC-17, Taipei, Taiwan, 337-343

Lathin, D., Mitchell, R. (2001) ―Learning from mistakes.‖ Quality Progr. 34(6) 39-45

Lean Construction Institute - LCI (2010) http://www.leanconstruction.org/

Lean Project Consulting (2010). http://www.leanproject.com/

Lillrank, P. (1994) ―Social Preconditions for Lean Management and its further

Development.‖ Enriching production Perspectives on Volvo‘s Uddevalla plant as

an alternative to lean production. Åke Sandberg, Ed., Swedish Institute for Work

Life Research, Stockholm, Sweden, 427-435 (Digital Edition, 2007)

Lilrank, P. (1995). ―The transfer of management innovations from Japan.‖

Organization studies, 16(6), 971-989

Lichtig, W.A. (2005). ―Sutter Health: Developing a Contracting Model to Support

Lean Project Delivery.‖ Lean Construction Journal, 2(1), April, 105-112.

McGill, M.E. and Slocum, J.W. (1993) ―Unlearning the Organization.‖

Organizational Dynamics. v.22, issue 2, 67-79

Ohno, T. (1988) Toyota Production System: beyond Large-Scale Production.

Productivity Press: Cambridge, Mass. 142pp.

Ollivella, J., Cuatrecasas, L., and Gavilan, N. (2008) ―Work organisation practices for

Lean Production‖, J. of Manufacturing Technology Mgmt., V. 19, n.7, 798-811

Pettersen, J. (2009) ―Defining Lean Production: some Conceptual and Practical

Issues‖ The TQM Journal, v.21, n.2. 127-142

Ramaswamy, K.P. and Kalidindi, S.N. (2009) ―Waste in Indian Building Construction

Projects.‖ Proceedings IGLC-17, Taipei, Taiwan, 10pp

Scott, F.M., Butler, J., and Edwards, J. (2001) ―Does Lean Production Sacrifice

Learning in a Manufacturing Environment? An Action Learning Case Study.‖

Studies in Continuing Education. V.23, n.2, 229-241

Shingo, S. (1989) A Study of the Toyota Production System. Productivity Press,

Portland, OR, 257pp.

Womack, J.P., Jones, D.T. and Ross, D. (1990) The Machine that Changed the World.

Harper Perennial: New York, NY. 323p.

Womack, J.P. and Jones, D.T. (2003). Lean Thinking. Free Press, New York, NY.

Proceedings IGLC-18, July 2010, Technion, Haifa, Israel

View publication stats

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Essential Social Studies Skills and Strategies PDFDocument4 pagesEssential Social Studies Skills and Strategies PDFSally Consumo KongNo ratings yet

- Exposure Management 2.0 - SAP BlogsDocument8 pagesExposure Management 2.0 - SAP Blogsapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Comparing Learning Theories Using The Dent-Read and Zukow-Goldring LearnerEnvironment MatrixDocument7 pagesComparing Learning Theories Using The Dent-Read and Zukow-Goldring LearnerEnvironment MatrixtracycwNo ratings yet

- ZoophonicsDocument2 pagesZoophonicsapi-273790468No ratings yet

- IP Appraisal Form Generic ERC VersionDocument2 pagesIP Appraisal Form Generic ERC VersionCarmenakiRapsNo ratings yet

- How To Download and Upload SAP Queries, Infosets and User Groups To Another Client or System (QAS, PRD) - SAP BlogsDocument17 pagesHow To Download and Upload SAP Queries, Infosets and User Groups To Another Client or System (QAS, PRD) - SAP Blogsapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Mastering TensorFlow Variables in 5 Easy Steps - KDnuggetsDocument9 pagesMastering TensorFlow Variables in 5 Easy Steps - KDnuggetsapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- How To Display Messages in A Popup Window in SAP - SAP BlogsDocument5 pagesHow To Display Messages in A Popup Window in SAP - SAP Blogsapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Accessing One Program Data in Another Program Easily Without Export and Import - Set and Get - SAPCODESDocument4 pagesAccessing One Program Data in Another Program Easily Without Export and Import - Set and Get - SAPCODESapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Carlborg 2013 - A Lean Approach For Service Productivity ImprovementsDocument14 pagesCarlborg 2013 - A Lean Approach For Service Productivity Improvementsapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Adjusting Table Maintenance Generator Without Re-Generating It, When Table Structure Changes - SAP BlogsDocument12 pagesAdjusting Table Maintenance Generator Without Re-Generating It, When Table Structure Changes - SAP Blogsapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Cavdur 2018 Lean Service System Design A Simulation-Based VSM Case StudyDocument20 pagesCavdur 2018 Lean Service System Design A Simulation-Based VSM Case Studyapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- SCM COP 2017 Grace Kumar CasestudywhatyoudontknowDocument42 pagesSCM COP 2017 Grace Kumar Casestudywhatyoudontknowapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Chauhan 2013, Resource Flexibility For Lean Manufacturing SAP-LAP Analysis of A Case Study PDFDocument19 pagesChauhan 2013, Resource Flexibility For Lean Manufacturing SAP-LAP Analysis of A Case Study PDFapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Ahmad 2014 - The Perceived Impact of JIT Implementation On Firms Financial Growth PerformanceDocument13 pagesAhmad 2014 - The Perceived Impact of JIT Implementation On Firms Financial Growth Performanceapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Bhasin 2013 - Impact of Corporate Culture On The Adoption of The Lean PrinciplesDocument23 pagesBhasin 2013 - Impact of Corporate Culture On The Adoption of The Lean Principlesapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Copying Roles From One SAP Client To Another Using PFCG - SAP BlogsDocument8 pagesCopying Roles From One SAP Client To Another Using PFCG - SAP Blogsapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Create FI Substitutions Using GGB1 (Substitution Maintenance) - SAP BlogsDocument7 pagesCreate FI Substitutions Using GGB1 (Substitution Maintenance) - SAP Blogsapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Cook Book - Configurable Material and Material Variants - Supply Chain Management (SCM) - Community WikiDocument7 pagesCook Book - Configurable Material and Material Variants - Supply Chain Management (SCM) - Community Wikiapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Authorization Trace in Transaction ST01 - Product Lifecycle Management - Community WikiDocument5 pagesAuthorization Trace in Transaction ST01 - Product Lifecycle Management - Community Wikiapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- SCM COP 2017 Barkman DigitalbusinessplanningstrategyDocument23 pagesSCM COP 2017 Barkman Digitalbusinessplanningstrategyapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- SCM COP 2017 Brassoe HowasimplestatisticalDocument65 pagesSCM COP 2017 Brassoe Howasimplestatisticalapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- SCM COP 2017 Bender ThefutureofdigitalDocument38 pagesSCM COP 2017 Bender Thefutureofdigitalapostolos thomasNo ratings yet

- Tutorial 01 Machine & Concept LearningDocument3 pagesTutorial 01 Machine & Concept LearningKNIGHT DARKNo ratings yet

- Subject Advisor School Visit Report Subject: Mechanical TechnologyDocument5 pagesSubject Advisor School Visit Report Subject: Mechanical TechnologyMphahamele ThabanyaneNo ratings yet

- Research 2Document18 pagesResearch 2Engelbert Bicoy AntodNo ratings yet

- Types of ReadingDocument19 pagesTypes of ReadingNursyazwani HamdanNo ratings yet

- Complete MOVDocument8 pagesComplete MOVLeoni Francis LagramaNo ratings yet

- L2-Stat. Prob - Distinguishing Between Discrete and Continuous Random VariableDocument7 pagesL2-Stat. Prob - Distinguishing Between Discrete and Continuous Random VariableRene Mulleta DueñasNo ratings yet

- Froforma-I (Subject Wise Formative Assessments)Document3 pagesFroforma-I (Subject Wise Formative Assessments)MD.khalilNo ratings yet

- Grade 7 ENG LAS MELC 1 Week 1. QTR 2Document5 pagesGrade 7 ENG LAS MELC 1 Week 1. QTR 2Stvn RvloNo ratings yet

- CSE 473 Pattern Recognition: Instructor: Dr. Md. Monirul IslamDocument57 pagesCSE 473 Pattern Recognition: Instructor: Dr. Md. Monirul IslamNadia Anjum100% (1)

- Ed 4 Module 7 Components of Special and Inclusive Education 2Document45 pagesEd 4 Module 7 Components of Special and Inclusive Education 2Veronica Angkahan SantiagoNo ratings yet

- Developing Speaking SkillsDocument7 pagesDeveloping Speaking SkillsEdén Verde Educación Con Salud0% (1)

- COURSE SYLLABUS in Principles...Document4 pagesCOURSE SYLLABUS in Principles...alohaNo ratings yet

- Computer Teaching Strategies (PRINT)Document6 pagesComputer Teaching Strategies (PRINT)aninNo ratings yet

- Research PaperDocument6 pagesResearch PaperSyed Shaaz MufeedNo ratings yet

- Graphic Design SyllabusIssued2011-2012Document2 pagesGraphic Design SyllabusIssued2011-2012johanmulyadi007No ratings yet

- Language and Literature AssessmentDocument62 pagesLanguage and Literature AssessmentAira Jane CruzNo ratings yet

- 1st Grading g9 Eating Habits July 30 Aug3Document6 pages1st Grading g9 Eating Habits July 30 Aug3Gene Edrick CastroNo ratings yet

- Tefl Teaching VocabDocument5 pagesTefl Teaching Vocabnurul vitaraNo ratings yet

- Daily Lesson Log: Domains 1. ObjectivesDocument4 pagesDaily Lesson Log: Domains 1. ObjectivesNathaniel Jose FullidoNo ratings yet

- DLL Final FormatDocument5 pagesDLL Final FormatMARIETTA DIANo ratings yet

- Báo cáo thực tập tốt nghiệp Nguyễn Thị Thanh KiềuDocument15 pagesBáo cáo thực tập tốt nghiệp Nguyễn Thị Thanh Kiềuanh.ntq281002No ratings yet

- SAT - English - Grade - 9 - 22-23 Academic Year - 1&4 TermsDocument64 pagesSAT - English - Grade - 9 - 22-23 Academic Year - 1&4 TermsDinara KasenovaNo ratings yet

- Ahmed ElmekahalDocument3 pagesAhmed ElmekahalAhmed MohammedNo ratings yet

- EDUC110Document2 pagesEDUC110Luisa AspirasNo ratings yet

- Effect of Instructional Materials On The Teaching and Learning of Basic Science in Junior Secondary Schools in Cross River State, NigeriaDocument7 pagesEffect of Instructional Materials On The Teaching and Learning of Basic Science in Junior Secondary Schools in Cross River State, NigeriaFemyte KonseptzNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan Eyl Home N FamilyDocument7 pagesLesson Plan Eyl Home N FamilySunardi AhmadNo ratings yet