Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Feudalism PDF

Uploaded by

Komal Meena0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

49 views2 pagesOriginal Title

Feudalism.pdf

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

49 views2 pagesFeudalism PDF

Uploaded by

Komal MeenaCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

Close This Window

More About

Feudalism

The term "feudalism" is used to refer to a political and economic

system in medieval Europe by which agriculture was conducted by

serfs on the manors of lords (suzerains) to whom they were bound by

oaths of loyalty and to whom they owed goods and services. These

lords owed goods and services, in turn, to suzerains above them, up a

hierarchical line to a king.

Seen from the top down, the king owned all land, which he granted

"in fief" to "vassals" (the people who were the suzerains when seen

from below) in exchange for goods and services (including support in

war). Depending upon the region, various titles such as knights and

squires, barons, counts, marquises, and so on were all part of this

system.

Characterized by the near complete sovereignty of a suzerain on

his fief and the total subordination of the serf to the suzerain, the

system was incompatible with strongly centralized political power

capable of connecting the king directly to the farming peasant, and

hence we do not see feudalism persisting after the establishment of

central strong monarchies in Europe.

Scholars differ on the extent to which they are willing to extend

the term "feudalism" as a general name for roughly similar

arrangements in other parts of the world, such as XVIIIth-century

Uganda, for example, or Bronze-Age China.

In the case of China, the application of the word is reasonably

common, since the Bronze-Age dynasties (the Shāng and the Zhōu) do

in fact seem to have involved an allocation of plots of land down a

hierarchy of vassals. This system obviously came to an end with the

assertion of direct centralized authority in the founding of the Qín

Dynasty in 221 BC, although occasional semi-feudal situations arose

from time to time in periods of dynastic breakdown for many

centuries thereafter.

This is not the way the term is used by Communist writers,

however. Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels spoke of a capitalist mode of

production, in which capitalists appropriated the "surplus value"

produced by industrial workers or "proletarians.". They contrasted this

with a rural equivalent, which they saw as a "feudal mode of

production," in which the "surplus value" produced by peasants was

appropriated by feudal lords in the form of rents, based not on market

forces, but on coercion. This seems not too far off from the classic

definition of feudalism, although it does not apply in most of the rural

world (especially today), since most rural society is not a world of

feudal lords and their peasants. However, Marx and Engels also

imagined a universal sequence of five broad stages in which rural

feudalism, the second stage, fell between earlier, "slave" society and

later, urban, "capitalist" society, which was to be followed by socialism

and eventually communism. In other words, feudalism became a stage

of development in all societies.

As Marxist analysis has been compulsorily applied by historians

writing under the intellectual oversight of the Chinese Communist

Party, the term "slave society" is applied to the Bronze Age (despite

that period being arguably feudal) and the term "feudal society" ( 封建

社会) is applied to the remainder of the dynastic period up until the

XXth century (despite the comparative absence of true feudalism

after the establishment of the centralized Qín administration in 221

BC).

In modern Chinese usage, the term "feudal" therefore has no

useful intellectual content, but is simply a mildly derogatory term for

Chinese society before the institutionalization of Communism in 1949.

Close This Window Print This Window

Content Revised: 2008-01-14

Software Last Modified: 2020-06-13

Search term: "feudalism" (Debugging)

You might also like

- Absolutism by MaryamDocument19 pagesAbsolutism by MaryamMaryam KhanNo ratings yet

- Feudalism in Africa 1Document18 pagesFeudalism in Africa 1Achamyeleh TamiruNo ratings yet

- The Empire Writes Back, Colonialism and PostcolonialismDocument4 pagesThe Empire Writes Back, Colonialism and PostcolonialismSaša Perović100% (1)

- Contradictions of Capitalism: An Introduction to Marxist EconomicsFrom EverandContradictions of Capitalism: An Introduction to Marxist EconomicsNo ratings yet

- PDFs/Sprinker NFPA 13/plan Review Sprinkler Checklist 13Document5 pagesPDFs/Sprinker NFPA 13/plan Review Sprinkler Checklist 13isbtanwir100% (1)

- Essay On Rise and Growth of Feudalism EuDocument7 pagesEssay On Rise and Growth of Feudalism EuBisht SauminNo ratings yet

- Karl Marx History of The Class Struggle TheoryDocument3 pagesKarl Marx History of The Class Struggle TheoryAminul IslamNo ratings yet

- Computer Systems Servicing NC II CGDocument238 pagesComputer Systems Servicing NC II CGRickyJeciel100% (2)

- The Regime Usury, Khazaria and The American MassDocument8 pagesThe Regime Usury, Khazaria and The American MassReuelInglisNo ratings yet

- Transition From Feudalism To CapitalismDocument8 pagesTransition From Feudalism To CapitalismRamita Udayashankar91% (34)

- Module 1 Unit 2 - Hardware and Software MGT PDFDocument7 pagesModule 1 Unit 2 - Hardware and Software MGT PDFRose Bella Tabora LacanilaoNo ratings yet

- Drawing Conclusions: LessonDocument6 pagesDrawing Conclusions: LessonMallari Fam0% (1)

- Feudalism DebateDocument128 pagesFeudalism DebateTarunNo ratings yet

- Summary Of "Pre-capitalist Economic Formations" By Eric Hobsbawm: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESFrom EverandSummary Of "Pre-capitalist Economic Formations" By Eric Hobsbawm: UNIVERSITY SUMMARIESNo ratings yet

- Edward Said Culture and ImperialismDocument6 pagesEdward Said Culture and ImperialismmairaNo ratings yet

- Impact of Child Labour On School Attendance and Academic Performance of Pupils in Public Primary Schools in Niger StateDocument90 pagesImpact of Child Labour On School Attendance and Academic Performance of Pupils in Public Primary Schools in Niger StateJaikes100% (3)

- Cap 1 16 Metamorfosis Ovidio PDFDocument22 pagesCap 1 16 Metamorfosis Ovidio PDFElias VergaraNo ratings yet

- Communism, Feudalism, CapitalismDocument4 pagesCommunism, Feudalism, CapitalismzadanliranNo ratings yet

- Horkheimer. M. On The Sociology of Class Relations.Document61 pagesHorkheimer. M. On The Sociology of Class Relations.Willian VieiraNo ratings yet

- European FeudalismDocument22 pagesEuropean FeudalismAleena Khan100% (1)

- Feudalism in Pakistan: A Myth or A Reality: Hammad RazaDocument4 pagesFeudalism in Pakistan: A Myth or A Reality: Hammad Razahammad razaNo ratings yet

- Republics & RepublicanismDocument18 pagesRepublics & Republicanism2ts8pbnhgfNo ratings yet

- Anderson, Perry - The Feudal Mode of ProductionDocument4 pagesAnderson, Perry - The Feudal Mode of Production4gen_7No ratings yet

- FIRST DRAFT Lit 652 Seminar in Global LiteratureDocument22 pagesFIRST DRAFT Lit 652 Seminar in Global LiteratureTom HopkinsNo ratings yet

- FINAL DRAFT Lit 652 Seminar in Global LiteratureDocument22 pagesFINAL DRAFT Lit 652 Seminar in Global LiteratureTom HopkinsNo ratings yet

- Marx Asiatic Mode of Production Oriental Despotism True SocialismDocument33 pagesMarx Asiatic Mode of Production Oriental Despotism True SocialismÇ. ÇağlarNo ratings yet

- FeudalismDocument5 pagesFeudalismRamita UdayashankarNo ratings yet

- Rise of Modern West-1 Assignment-1Document5 pagesRise of Modern West-1 Assignment-1Sajal S.KumarNo ratings yet

- HC 3 Middle AgesDocument41 pagesHC 3 Middle AgesluukbruijnenNo ratings yet

- Evgeny Pashukanis - Lenin and Problems of LawDocument33 pagesEvgeny Pashukanis - Lenin and Problems of LawJowfullNo ratings yet

- The Transition Debate On The Origin of FeudalismDocument7 pagesThe Transition Debate On The Origin of FeudalismBisht SauminNo ratings yet

- Asgn 2 Comparative Theories of Development IDocument35 pagesAsgn 2 Comparative Theories of Development IMazLinaNo ratings yet

- Social Formations FarooquiDocument12 pagesSocial Formations FarooquiNachiket KulkarniNo ratings yet

- FEUDALISM Definition EssayDocument2 pagesFEUDALISM Definition EssayEleni MoschouNo ratings yet

- PDF document-AF1BA08E8E3F-1Document49 pagesPDF document-AF1BA08E8E3F-1Taha HassanNo ratings yet

- The Communist ManifestoDocument4 pagesThe Communist ManifestoValeria LeyceguiNo ratings yet

- The Absolutist State in The West in Lineages of The Absolutist StateDocument17 pagesThe Absolutist State in The West in Lineages of The Absolutist StateMariel Cameras MyersNo ratings yet

- Feudalism in AfricaDocument19 pagesFeudalism in AfricaAlice Soares GuimarãesNo ratings yet

- TakahashiDocument34 pagesTakahashiSumegha JainNo ratings yet

- Feudalism DebateDocument10 pagesFeudalism DebateAshmit RoyNo ratings yet

- The Concept of Hegemony-Bourgeois Hysteria and The Carnivalesque - Dancing at LughnasaDocument21 pagesThe Concept of Hegemony-Bourgeois Hysteria and The Carnivalesque - Dancing at LughnasaNurgül KeşkekNo ratings yet

- A Review of The Debates On The TransitioDocument9 pagesA Review of The Debates On The TransitioWe TrendsNo ratings yet

- What Is Feudalism? - Definition, Complex, CivilizationDocument14 pagesWhat Is Feudalism? - Definition, Complex, CivilizationNoorSabaNo ratings yet

- Unit-20 Debates On FeudalismDocument14 pagesUnit-20 Debates On FeudalismAlok ThakkarNo ratings yet

- Structure of Indian FeudalismDocument14 pagesStructure of Indian Feudalismadarsh aryanNo ratings yet

- Unit 1Document10 pagesUnit 1ALBERTO MORALES JOVERNo ratings yet

- The State-Organized Progress or Decay ProductDocument28 pagesThe State-Organized Progress or Decay ProductReto LanoNo ratings yet

- BourgeoisieDocument10 pagesBourgeoisiePablo Daniel AlmirónNo ratings yet

- MarxismDocument5 pagesMarxismNikita SinghNo ratings yet

- Ottoman FeudalismDocument13 pagesOttoman Feudalismmarathosioannis7623No ratings yet

- Hann, Economic Anthropology Encyclopedia ArticleDocument16 pagesHann, Economic Anthropology Encyclopedia ArticlejorgekmpoxNo ratings yet

- The Origins of Nation Formation and Nationalism in EuropeDocument10 pagesThe Origins of Nation Formation and Nationalism in EuropeJohn GajusNo ratings yet

- Transition Debate 1Document11 pagesTransition Debate 1Archita JainNo ratings yet

- Aristocracy - WikipediaDocument17 pagesAristocracy - WikipediaJesNo ratings yet

- Feudalism - Nikhil PandhiDocument17 pagesFeudalism - Nikhil PandhiRohit GunasekaranNo ratings yet

- Futures Volume 6 Issue 3 1974 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (74) 90052-4) John Sanderson - 3.1. Demystifying The Historical Process - Karl MarxDocument6 pagesFutures Volume 6 Issue 3 1974 (Doi 10.1016/0016-3287 (74) 90052-4) John Sanderson - 3.1. Demystifying The Historical Process - Karl MarxManticora VenerabilisNo ratings yet

- Marxism and NationalismDocument22 pagesMarxism and NationalismKenan Koçak100% (1)

- Between Market StateDocument24 pagesBetween Market StateJoerie OsaerNo ratings yet

- Absolutism in Western EuropeDocument6 pagesAbsolutism in Western Europe1913 Amit YadavNo ratings yet

- Feudalism PDFDocument4 pagesFeudalism PDFAchint KaurNo ratings yet

- Reading About MarxDocument3 pagesReading About MarxAnonymous 9FOneuPy0No ratings yet

- Vasiliev On The Question of Byzantine FeudalismDocument22 pagesVasiliev On The Question of Byzantine FeudalismHomo Byzantinus100% (1)

- Written Assignment Unit 4aDocument4 pagesWritten Assignment Unit 4aTom GrandNo ratings yet

- Marx, Lenin and The "Dictatorship of The Proletariat"Document4 pagesMarx, Lenin and The "Dictatorship of The Proletariat"Aroon KumarNo ratings yet

- History: (For Under Graduate Student)Document15 pagesHistory: (For Under Graduate Student)zeba abbasNo ratings yet

- Modified Doc of Early Medieval Indian Feudalism by Tuliip BiswasDocument11 pagesModified Doc of Early Medieval Indian Feudalism by Tuliip BiswasRafig UddinNo ratings yet

- Hill Areas Development Programme (HADP)Document10 pagesHill Areas Development Programme (HADP)Komal MeenaNo ratings yet

- Feudalism DebateDocument10 pagesFeudalism DebateAshmit RoyNo ratings yet

- Modified Doc of Early Medieval Indian Feudalism by Tuliip BiswasDocument11 pagesModified Doc of Early Medieval Indian Feudalism by Tuliip BiswasRafig UddinNo ratings yet

- Building ProcessDocument25 pagesBuilding Processweston chegeNo ratings yet

- Valuation of Bonds and Stocks: Financial Management Prof. Deepa IyerDocument49 pagesValuation of Bonds and Stocks: Financial Management Prof. Deepa IyerAahaanaNo ratings yet

- S.No Company Name Location: Executive Packers and MoversDocument3 pagesS.No Company Name Location: Executive Packers and MoversAli KhanNo ratings yet

- Manual de Usuario PLECSIM 4.2Document756 pagesManual de Usuario PLECSIM 4.2juansNo ratings yet

- Basic Principle of Semiconductor DiodesDocument5 pagesBasic Principle of Semiconductor DiodessatishasdNo ratings yet

- Least Used ProtocolsDocument3 pagesLeast Used ProtocolsJohn Britto0% (1)

- MEP Works OverviewDocument14 pagesMEP Works OverviewManoj KumarNo ratings yet

- Transmission Line4 PDFDocument46 pagesTransmission Line4 PDFRevathi PrasadNo ratings yet

- Skott Marsi Art Basel Sponsorship DeckDocument11 pagesSkott Marsi Art Basel Sponsorship DeckANTHONY JACQUETTENo ratings yet

- Modelling and Simulation of Armature ControlledDocument7 pagesModelling and Simulation of Armature ControlledPrathap VuyyuruNo ratings yet

- Automotive Workshop Practice 1 Report - AlignmentDocument8 pagesAutomotive Workshop Practice 1 Report - AlignmentIhsan Yusoff Ihsan0% (1)

- Liebert Exs 10 20 Kva Brochure EnglishDocument8 pagesLiebert Exs 10 20 Kva Brochure Englishenrique espichan coteraNo ratings yet

- Design of Earth Air Tunnel To Conserve Energy - FinalDocument19 pagesDesign of Earth Air Tunnel To Conserve Energy - FinalApurva AnandNo ratings yet

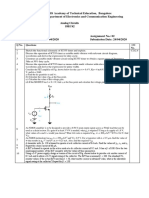

- Q No. Questions CO No.: C C W That Results in GDocument2 pagesQ No. Questions CO No.: C C W That Results in GSamarth SamaNo ratings yet

- 6-GFM Series: Main Applications DimensionsDocument2 pages6-GFM Series: Main Applications Dimensionsleslie azabacheNo ratings yet

- In-N-Out vs. DoorDashDocument16 pagesIn-N-Out vs. DoorDashEaterNo ratings yet

- NDA Report No DSSC-452-01 - Geological Disposal - Engineered Barrier System Status ReportDocument146 pagesNDA Report No DSSC-452-01 - Geological Disposal - Engineered Barrier System Status ReportVincent LinNo ratings yet

- Metric Tables 2012Document2 pagesMetric Tables 2012ParthJainNo ratings yet

- Casio fx-82MSDocument49 pagesCasio fx-82MSPéter GedeNo ratings yet

- Schindler's List Theme Sheet Music For Piano, Violin (Solo)Document1 pageSchindler's List Theme Sheet Music For Piano, Violin (Solo)Sara SzaboNo ratings yet

- 1.1.4.A PulleyDrivesSprockets FinishedDocument4 pages1.1.4.A PulleyDrivesSprockets FinishedJacob DenkerNo ratings yet

- Business Models, Institutional Change, and Identity Shifts in Indian Automobile IndustryDocument26 pagesBusiness Models, Institutional Change, and Identity Shifts in Indian Automobile IndustryGowri J BabuNo ratings yet

- LGC CasesDocument97 pagesLGC CasesJeshe BalsomoNo ratings yet

- File System ImplementationDocument35 pagesFile System ImplementationSát Thủ Vô TìnhNo ratings yet

- Carreño Araujo Cesar - Capturas Calculadora Sesion 02Document17 pagesCarreño Araujo Cesar - Capturas Calculadora Sesion 02CESAR JHORCHS EDUARDO CARREÑO ARAUJONo ratings yet