Professional Documents

Culture Documents

What Are Some of The Key Issues Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?

Uploaded by

api-525572712Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

What Are Some of The Key Issues Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?

Uploaded by

api-525572712Copyright:

Available Formats

Assessment 2: Essay

What are some of the key issues teachers need to consider for working successfully with Aboriginal and

Torres Strait Islander students?

In today’s educational system, providing Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students with the best and

most suitable education possible is becoming a prominent goal. In order to do this, there are a range of

issues teachers need to understand and consider to successfully communicate, work with and provide

suitable materials and experiences for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander students. This essay will first

discuss the guiding standards for teachers and their interactions with Indigenous Australians found in the

Australian Professional Standards for Teachers (AITSL, 2014). Subsequently, the key issues teachers must

consider will be examined, with consideration given to the contributing factors and implications of these

issues. In particular, three issues present as a result of the history of Australia and Indigenous Australians

will be discussed, including the Stolen Generation, acknowledgment of Indigenous Australian history and

identity, and the perception of Indigenous Australians as uneducable. Additionally, the issues of

stereotyping, the Closing the Gap Campaign, and differing values and learning styles will be discussed to

explore the key issues that must be considered to work effectively with Indigenous Australian students.

Throughout this discussion, the term ‘Indigenous Australians’ will inclusively refer to Aboriginal and Torres

Strait Islander peoples.

One of the most significant issues teacher’s must consider for working successfully with Indigenous

Australian students is the history of Australia and Indigenous Australians. As this history is extensive, there

are a number of key elements that must be considered, including the Stolen Generation, Indigenous

Australian identity, and the perception of Indigenous Australian peoples as uneducable.

In educational settings, it is vital that teachers have an understanding of the Assimilation Policies and

resulting Stolen Generations to successfully work with Indigenous Australian students. Specifically, the

Assimilation Policies were created to assimilate the ‘mixed-race’ population (Indigenous Australians) into

the ‘white’ population, eventually breeding the Aboriginal blood out (Carter, 2006). Consequently, the term

‘Stolen Generations’ refers to the tens of thousands of children who were forcibly removed from their

families by authorities as a result of the Assimilation Policies (Beresford, 2012). As indicated by Macoun

(2011), this removal was supposedly further justified as Indigenous Australian children were thought to

represent the vulnerable children of Australia; urgently needing to be saved from abuse and victimisation by

their caregivers. Ironically, as discussed later in the essay, many studies now indicate that Indigenous

Australian Children do represent a significant portion of the vulnerable children of Australia (Biddle, 2011).

Thus, it is important for teachers to have an understanding of these events because, as Williams Mozley

(2012) indicates, the memory of forced removal is not historic, distant or remote; instead it is re-lived daily

EDUC 2061 Teaching and Learning in Aboriginal Education Page 1 of 6

Lewanna Hampel, Student ID: 110232121, Tutor: Michelle Simmons

by many Indigenous Australians. Subsequently, it is important not to disregard the Stolen Generation as

Indigenous Australian students and their learning may still be affected by this. For example, as the Stolen

Generation resulted in Indigenous Australian children being placed within institutions, it is important to

consider that many Indigenous Australian peoples have little faith in the education system and thus may be

concerned about leaving their children at school (Phillips and Lampert, 2005). Likewise, Indigenous students

themselves may be concerned about staying at school. Catering for these concerns, teachers’ must ensure

they create a welcoming learning environment in which both Indigenous Australian parents and students

feel comfortable within and can develop trusting relationships.

Closely linked to the Stolen Generations, a second key historical issues teachers’ must consider to

successfully work with Indigenous Australian students is the loss of identity many Indigenous Australians

experienced, and still feel the effects of today. Specifically, the separation of Indigenous Australian families

as a result of the Assimilation Policies, in conjunction with the loss of traditional land, was a significant factor

influencing the loss of identity for Indigenous Australians. This is emphasised by Williams-Mozley (2012) who

discusses his loss of identity as a result of being denied access to his language, culture, land and family.

Likewise, the loss of stories previously passed from generation to generation have contributed to this identity

loss; separation permanently disrupting this process for many Indigenous Australians (Behrendt, 1995).

Indigenous Australian peoples Identity loss may also be attributed to by the misrepresentation of Australian

history. As discussed by Carter (2006), many Australian history books feature common misleading themes,

such as the process of colonisation was relatively peaceful and uncomplicated, and that the disposition and

destruction of Aboriginal society was inevitable. Consequently, while today’s society has a greater

understanding of what really happened, many people seek to consciously ignore this history as they struggle

to comprehend that their great nation could have such an appalling past. However, as O’Brien (2007)

indicates, the only way of creating a better future is to recognise the bad experiences from the past, rather

than ignoring them. Thus, it is extremely important that teachers provide abundant opportunities for

children to explore and develop their identity in a supportive environment. For example, teachers may

encourage the exploration of identity by playing different Indigenous Australian music in the classroom;

either as background music during additional activities or as a focus activity where students can dance and

express themselves. Simultaneously developing students sense of belonging, this music could be sourced

from the families of Indigenous Australian students within the class or school. Likewise, teachers’ can

support the success of working with Indigenous Australian students by acknowledging the ‘true’ history of

Australia. This may be done by discussing the history of Australia by inviting local Indigenous Australian

community members, or an Indigenous Australian person with ties to an Indigenous Australian student

within the school, into the classroom to share their experiences. As aspects of this history may not be suited

EDUC 2061 Teaching and Learning in Aboriginal Education Page 2 of 6

Lewanna Hampel, Student ID: 110232121, Tutor: Michelle Simmons

for younger children, Australian history may be acknowledged in other ways, including through the action of

completing an Acknowledgment of Country at the beginning of the school day.

For teachers seeking to successfully work with Indigenous Australian students, it is essential they consider

the historical perception of Indigenous Australians as uneducable and the implications of this perception on

students learning. As discussed by Price (2012), the myth that Indigenous Australians are uneducable is

believed to have been developed by early European settlers. Accordingly, the idea that Indigenous Australian

children lacked the intellectual capacity to be educated beyond third grade and consequently required only

minimal access to schooling was widely accepted within society (Beresford, 2012). This limited education

was further perceived as suitable as it reflected Indigenous Australians expected place in white society; at

the bottom (Beresford, 2012). Within the limited education Indigenous Australian children received, the

focus was believed to be on preparing them for their future as unskilled workers (Price, 2012). Consequently,

today’s research lends itself towards the conclusion that the generations of uneducated and partly educated

Indigenous Australian peoples are in fact the result of these poor provisions for Indigenous Australian

children in the past (Beresford, 2012). In the aims of providing Indigenous Australian students with the best

education possible, it is vital that teachers ensure they treat all of their students, including the students’

backgrounds and cultures, equally and with respect. Additionally, within their practices teachers must ensure

the perception of Indigenous Australians as uneducable is in no way present. Maintaining professional

practices, this will also reassure Indigenous Australian parents’ concerns, including the concern raised by one

parent in Gollan and Malin (2012, pp. 151); ‘please do not classify my son as disadvantaged the minted he

steps through the door.’ Likewise, teachers must reflect on the impact the limited education has had on

Indigenous Australian parents and consequently now has on their children. For example, teachers should try

not to overemphasise the importance of children reading at home with assistance from their parents as a

number of Indigenous Australian parents were never taught how to read. Consequently, readings for

homework may not be completed as Indigenous Australian parents may be unable to help their children.

Thus, in order to successfully work with Indigenous Australian students, teachers need to regard the myth

of Indigenous Australians as uneducable as false and likewise consider the after effects of this perception on

both their Indigenous Australian students and their parents.

As highlighted by the example of perceiving Indigenous Australians as uneducable, an additional key issue

teachers must consider to work successfully with Indigenous Australian students is the issue of stereotyping.

While stereotyping of Indigenous Australian peoples may be considered by some as inexistent in today’s

society compared to historically, this is not the case. Instead, it is still a significant issue and includes

stereotypes such as that all Indigenous Australians live in the ‘middle of no-where,’ eat food from the bush

or that Indigenous Australians are unemployable and alcoholics. In an educational setting, it is vital that

EDUC 2061 Teaching and Learning in Aboriginal Education Page 3 of 6

Lewanna Hampel, Student ID: 110232121, Tutor: Michelle Simmons

teachers do not conform with these stereotypes because, not only are they untrue, but teachers own views

are reflected in their attitudes and expectations (Phillips and Lampert, 2005). Consequently, these views

influence teachers’ interactions with their students and, as Harrison (2011) indicates, may rub off on the

students and create powerful discourses that position Indigenous Australians in negative places. Thus, to

successfully work with Indigenous Australian, students’ teachers should question stereotypes and utilise

practices that do not support these, such as holding high expectations of Indigenous Australian students to

convey that they have just as much potential to succeed as non-Indigenous Australian students (Harrison,

2011).

Launched in 2007, the Closing the Gap Campaign highlights a number of key issues teachers must consider

to effectively work with Indigenous Australian students. Labelled it a ‘national responsibility that belongs

with every Australian’ (DPMC, 2015), the campaign aims to ‘close the gap’ between Indigenous and non-

Indigenous Australians within a number of areas, including employment, health and education. Indicating

the importance of Indigenous Australian education, three targets are specifically aimed at educational

participation and attainment. These targets involve closing the gap in school attendance, halving the gap in

Year 12 attainment and halving the gap in reading and numeracy for Indigenous students (DPMC, 2015).

Accordingly, the ninth Closing the Gap Report indicates that the reading and numeracy target is not on track,

neither is the attendance target with the attendance rate for Indigenous Australian students decreasing by

0.1 per cent from 2014 to 2016 (83.4). Positively, the Report indicates an increase of approximately 15 per

cent in Year 12 attainment between 2008 and 2014-15 (Biddle, 2011; DPMC, 2015). Consequently, the

Government has indicated that intensive support is being provided for those in communities who are at risk

of falling behind because they believe that success in education creates the foundation for success in later

life (DPMC, 2015). For educators, this campaign indicates the significant progress that needs to be made

when working with Indigenous Australian students. To aid in this progress and increase success when

working with Indigenous Australians students, teachers must utilise flexible and engaging strategies that are

compatible with students and the context in which they learn best (Hyde, Carpenter and Conway, 2014).

Supporting identity and a sense of belonging development, this supportive environment can be created by

working closely with the local community to provide contextually appropriate learning experiences, for

example students in Adelaide may visit Colebrook Home. Notably, teachers must also have an understanding

of the other Closing the Gap targets and the reasons for these, including the significantly younger life

expectancy of Indigenous Australians; partly attributed to the higher rates of chronic disease than in non-

Indigenous Australians (Biddle, 2011). Through this understanding, teachers can better work with Indigenous

Students as they will have a greater understanding of the issues within the local community that may affect

their Indigenous Australian students and their families.

EDUC 2061 Teaching and Learning in Aboriginal Education Page 4 of 6

Lewanna Hampel, Student ID: 110232121, Tutor: Michelle Simmons

By acknowledging that Indigenous Australian peoples culture and background is significantly different to

non-Indigenous Australians, it is comprehendible that Indigenous Australians have different views and

learning styles than non-Indigenous Australians (Hyde, Carpenter and Conway, 2014). Consequently, to work

with and support the learning of Indigenous Australian students, teachers need to have an understanding of

these views and learning styles. As discussed by Martin (2005), traditionally Indigenous Australian children

were taught by example and brought up as capable, active contributors of their community. Likewise,

Indigenous Australian children were brought up to look after each other, rather than being looked after by

their parents all the time (Martin, 2005). Within a classroom, it is important that teachers consider these

values, especially when observing children as, for example, Indigenous Australian children may be more

inclined to work successfully when a task is demonstrated or when they can work collaboratively. Similarly,

Indigenous Australian children may be observed helping others more than focusing on their own work (Van

Hoorn et al., 2015). In understanding the reasoning behind these actions, teachers can ensure they do not

make incorrect assumptions, such as assuming a child helps others to get out of their own work.

Furthermore, these values assist educators to understand that Indigenous Austrian persons may not value

particular aspects of education as much as non-Indigenous Australians as they do not see the practical

purposes, such as learning algebra (Martin, 2005). Subsequently, teachers of Indigenous Australians may

seek to incorporate more hands-on activities and provide frequent demonstrations to enable students

learning through imitation. Similarly, they may relate in class activities to real-life experiences, highlighting

the benefits and purpose of the learning. Supporting their pedagogy and the delivery of experiences that

cater for learning differences and views, teachers should also utilise the Austrian Curriculum (ACARA, 2016)

cross-cultural priorities: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Histories and Cultures. In particular, the

Curriculums conceptual framework for Indigenous Australian Histories and Cultures priority emphasises the

importance of Indigenous Australian culture, communities and connections to Country/Place (ACARA, 2016).

EDUC 2061 Teaching and Learning in Aboriginal Education Page 5 of 6

Lewanna Hampel, Student ID: 110232121, Tutor: Michelle Simmons

Reference List

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) 2016, The Australian Curriculum,

ACARA, viewed 22 September 2017, < https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/>.

Australian Government Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (DPMC) 2015, ‘Executive Summary,’

Closing the Gap, viewed 22 September 2017, <http://closingthegap.pmc.gov.au/executive-summary>.

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) 2014, Australian Professional Standards for

Teachers, AITSL, Australian Government, viewed 21 September 2017,

<https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards>.

Behrendt, L. 1995, Aboriginal Dispute Resolution, Federation Press, Maryborough, Victoria, pp. 12-30.

Beresford, Q 2012, ‘Separate and unequal: An outline of Aboriginal Education 1900-1996’ in Beresford, Q,

Partington, G and Gower, G (eds.), Reform and Resistance in Aboriginal Education, UWA Publishing.

Biddle, N 2011, ‘Education Part 2: School Education,’ CAEPR Indigenous Population Project: 2011 Census

Papers, Australian National University, pdf, viewed 22 September 2017,

<http://caepr.anu.edu.au/sites/default/files/cck_indigenous_outcomes/2013/05/2011CensusPaper08_Edu

cation_Part2_Web.pdf)

Carter, D 2006 ‘Aboriginal history and Australian history’ in Dispossession, dreams and diversity: Issues in

Australian studies, Pearson Education, Frenchs Forest, NSW.

Gollan, S and Malin, M 2012, ‘Teachers and families working together to build stronger futures for our

children in school’ in Beresford, Q, Partington, G and Gower, G (eds) Reform and Resistance in Aboriginal

Education, UWA Publishing, pp. 149 -174.

Harrison, N 2011, ‘Starting out as a teacher in Aboriginal education’, Teaching and Learning in Aboriginal

education, 2nd edn, Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Vic., pp. 1-16.

Hyde, M, Carpenter, L & Conway, R 2010, Diversity, Inclusion & Engagement, 2nd edn, Oxford University

Press, Australia.

Macoun, A 2011, ‘Aboriginality and the Northern Territory Intervention’, Australian Journal of Political

Science, vol. 46, no. 3, pp. 519-534.

Martin, K 2005, Childhood, lifehood and relatedness: Aboriginal ways of being, knowing and doing’ in

Phillips, J and Lampert, J (eds) Education and diversity in Australia, Pearson Education Australia, Frenchs

Forest, NSW.

O’Brien, L 2007, ‘Sharing our space’ in And the clock struck thirteen, Wakefield press, Adelaide.

Phillips and Lampert 2005, ‘Indigenous Education: Curriculum: a doorway to learning’ in Education and

Diversity in Australia, Pearson Education Australia, Frenchs Forest, NSW, pp. 140-160.

Price, K 2012, ‘A brief history of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander education in Australia’ in K Price

(ed) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education: An introduction for the teaching profession, Cambridge

University Press, Sydney, NSW, pp. 1 – 20.

Van Hoorn, J, Nourot, P, Scales, B & Alward, K 2015, Play at the center of the curriculum, 6th edn, Pearson,

Boston.

Williams-Mozley, J 2012, ‘The Stolen Generations: What does this mean for Aboriginal and Torres Strait

Islander children and young people today’ in K Price (ed) Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education: An

introduction for the teaching profession, Cambridge University Press, Sydney, NSW, pp. 21 – 34.

EDUC 2061 Teaching and Learning in Aboriginal Education Page 6 of 6

Lewanna Hampel, Student ID: 110232121, Tutor: Michelle Simmons

You might also like

- Diversity in American Schools and Current Research Issues in Educational LeadershipFrom EverandDiversity in American Schools and Current Research Issues in Educational LeadershipNo ratings yet

- What Are Some of The Key Issues Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?Document4 pagesWhat Are Some of The Key Issues Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?api-525572712No ratings yet

- The Black Socio-Cultural Cognitive Learning Style HandbookFrom EverandThe Black Socio-Cultural Cognitive Learning Style HandbookNo ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document8 pagesAssignment 2api-360867615No ratings yet

- Aboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assessment 1 - Option 2Document12 pagesAboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assessment 1 - Option 2api-321112414No ratings yet

- Rachael-Lyn Anderson EDED11458 LetterDocument14 pagesRachael-Lyn Anderson EDED11458 LetterRachael-Lyn AndersonNo ratings yet

- Acrp EssayDocument10 pagesAcrp Essayapi-357686594No ratings yet

- Personal Reflection About Aboriginal StudentsDocument6 pagesPersonal Reflection About Aboriginal Studentsapi-409104264No ratings yet

- Assignment 2: Essay William CreeperDocument6 pagesAssignment 2: Essay William Creeperapi-523656984No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Ed. Essay - Moira McCallum FinalDocument8 pagesAboriginal Ed. Essay - Moira McCallum Finalmmccallum88No ratings yet

- Catherine Spear Assignment 2Document7 pagesCatherine Spear Assignment 2api-471129422No ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning in Aboriginal Education: Assessment Two - EssayDocument6 pagesTeaching and Learning in Aboriginal Education: Assessment Two - Essayapi-465726569No ratings yet

- Aboriginal EssayDocument4 pagesAboriginal Essayapi-471893759No ratings yet

- Essay: Tiarna Said - Student ID # 110186242Document5 pagesEssay: Tiarna Said - Student ID # 110186242api-529553295No ratings yet

- ABORIGINAL and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies EssayDocument9 pagesABORIGINAL and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Essayapi-408471566No ratings yet

- Edfd 546 Assignment 2 Part B 2-Pages-2-5Document4 pagesEdfd 546 Assignment 2 Part B 2-Pages-2-5api-239329146No ratings yet

- Educ2061 Sweeney EssayDocument9 pagesEduc2061 Sweeney Essayapi-496910396No ratings yet

- EDUC5429 EssayDocument11 pagesEDUC5429 EssayRuiqi.ngNo ratings yet

- EssayDocument7 pagesEssayapi-413124479No ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document5 pagesAssignment 2api-520251413No ratings yet

- What Are Some of The Key Issues' Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?Document4 pagesWhat Are Some of The Key Issues' Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?api-465449635No ratings yet

- Essay One Abos InclusionDocument8 pagesEssay One Abos Inclusionapi-298634756No ratings yet

- Critically Reflective EssayDocument9 pagesCritically Reflective Essayapi-478766515No ratings yet

- Diversity Social Justice and Learning - Essay 1Document9 pagesDiversity Social Justice and Learning - Essay 1api-332379661No ratings yet

- 1 4 Assignment 3 Essay Yr1 sm1Document7 pages1 4 Assignment 3 Essay Yr1 sm1api-319400168No ratings yet

- What Are Some of The Key Issues Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?Document7 pagesWhat Are Some of The Key Issues Teachers Need To Consider For Working Successfully With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Students?api-466211303No ratings yet

- Indigenous EducationDocument9 pagesIndigenous Educationapi-358031609No ratings yet

- Critical Review Claudia Norris-GreenDocument5 pagesCritical Review Claudia Norris-Greenapi-361866242No ratings yet

- Keer Zhang 102085 A2 EssayDocument13 pagesKeer Zhang 102085 A2 Essayapi-460568887100% (1)

- Aboriginal Education Essay2 FinalDocument5 pagesAboriginal Education Essay2 Finalapi-525722144No ratings yet

- Diversity Assessment 1Document7 pagesDiversity Assessment 1api-357575377No ratings yet

- Aboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assignment 1Document8 pagesAboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assignment 1api-332411347No ratings yet

- Indigenous StudentsDocument10 pagesIndigenous Studentsapi-463933980No ratings yet

- Reconciliation EssayDocument8 pagesReconciliation Essayapi-294443260No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Education EssayDocument7 pagesAboriginal Education Essayappy greg100% (2)

- Social JusticeDocument6 pagesSocial Justiceapi-375389014No ratings yet

- Gianduzzo Robert 1059876 Task1 Edu410Document11 pagesGianduzzo Robert 1059876 Task1 Edu410api-297391450No ratings yet

- 2Document6 pages2api-519322453No ratings yet

- Assessment 2Document6 pagesAssessment 2api-464657410No ratings yet

- Teaching and Learning in Aboriginal EducationDocument5 pagesTeaching and Learning in Aboriginal Educationapi-433788836No ratings yet

- Aboriginal EssayDocument5 pagesAboriginal Essayapi-428484559No ratings yet

- At 2 Apst 2Document3 pagesAt 2 Apst 2api-457784453No ratings yet

- Essay On BarriersDocument8 pagesEssay On Barriersapi-293919801No ratings yet

- Indigenous PerspectivesDocument27 pagesIndigenous Perspectivesapi-222614545No ratings yet

- Acrp - 2k Assessment - 2020Document9 pagesAcrp - 2k Assessment - 2020api-554503396No ratings yet

- Acrp Assessment 2 EssayDocument9 pagesAcrp Assessment 2 Essayapi-533984328No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assignment 1Document11 pagesAboriginal Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assignment 1api-435535701100% (1)

- Assignment 2 EssayDocument3 pagesAssignment 2 Essayapi-526121705No ratings yet

- Acrp Essay - Rachel Jolly 19665131Document9 pagesAcrp Essay - Rachel Jolly 19665131api-553761934No ratings yet

- Essay Hist106Document6 pagesEssay Hist106api-358162850No ratings yet

- The Conditions Impacting On Indigenous Students' EducationDocument4 pagesThe Conditions Impacting On Indigenous Students' Educationapi-474906540No ratings yet

- Assignment 2Document7 pagesAssignment 2api-350319898No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Assignment 20Document5 pagesAboriginal Assignment 20api-369717940No ratings yet

- Critically Reflective EssayDocument7 pagesCritically Reflective Essayapi-460524150No ratings yet

- Assignment 2 Aboriginal Education Isabel SarreDocument6 pagesAssignment 2 Aboriginal Education Isabel Sarreapi-465723124No ratings yet

- Aboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assessment 1Document9 pagesAboriginal and Culturally Responsive Pedagogies Assessment 1api-321128505No ratings yet

- Aboriginal Student Stories, The Missing Voice To Guide Us Towards ChangeDocument13 pagesAboriginal Student Stories, The Missing Voice To Guide Us Towards ChangeAllan LoNo ratings yet

- Diversity and Social Justice Assignment OneDocument10 pagesDiversity and Social Justice Assignment Oneapi-357666701No ratings yet

- Assignment 1 Harry SohalDocument7 pagesAssignment 1 Harry Sohalapi-355551741No ratings yet

- Diversity AssessmentDocument9 pagesDiversity Assessmentapi-554490943No ratings yet

- ASSESSMENT 2: Planning For Intervention: EDUC 3007 Managing Learning EnvironmentsDocument7 pagesASSESSMENT 2: Planning For Intervention: EDUC 3007 Managing Learning Environmentsapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument1 pageScanned With Camscannerapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Evidence StatementDocument2 pagesEvidence Statementapi-525572712No ratings yet

- ASSESSMENT 2: Preventative Planning: EDUC 3007 Managing Learning EnvironmentsDocument6 pagesASSESSMENT 2: Preventative Planning: EDUC 3007 Managing Learning Environmentsapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Communication: Critical Issues of Diversity and AccommodationsDocument3 pagesCommunication: Critical Issues of Diversity and Accommodationsapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Week 7 Lesson: Writing FocusDocument1 pageWeek 7 Lesson: Writing Focusapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument1 pageScanned With Camscannerapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Apst 3.3 Range of Teaching Strategies LogDocument2 pagesApst 3.3 Range of Teaching Strategies Logapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Weeks 6 - 8 Term 3 Mathematics Topic: ChanceDocument8 pagesWeeks 6 - 8 Term 3 Mathematics Topic: Chanceapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Visual ArtsDocument6 pagesVisual Artsapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Posters Created With Students During A Brainstorm On Ideas For Their DinosaurDocument1 pagePosters Created With Students During A Brainstorm On Ideas For Their Dinosaurapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Evidence Statement: FocusDocument1 pageEvidence Statement: Focusapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument1 pageScanned With Camscannerapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Targeted Chance Support: Group 1 Difference Between Certain and LikelyDocument2 pagesTargeted Chance Support: Group 1 Difference Between Certain and Likelyapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument2 pagesScanned With Camscannerapi-525572712No ratings yet

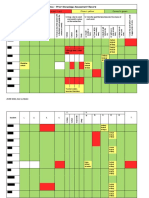

- Not Attempted White Incorrect Red Close Yellow Correct Green StudentDocument4 pagesNot Attempted White Incorrect Red Close Yellow Correct Green Studentapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Formal Assessment: Assessment Strategies For Assessing Student LearningDocument2 pagesFormal Assessment: Assessment Strategies For Assessing Student Learningapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Weeks 6 - 8 Term 3 Mathematics Topic: ChanceDocument8 pagesWeeks 6 - 8 Term 3 Mathematics Topic: Chanceapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument2 pagesScanned With Camscannerapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Weeks 8, 9 & 10, Term 3 Maths Topic: DataDocument5 pagesWeeks 8, 9 & 10, Term 3 Maths Topic: Dataapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument2 pagesScanned With Camscannerapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument2 pagesScanned With Camscannerapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Evaluation of The Lesson I Taught: Lab School Teaching PackageDocument2 pagesEvaluation of The Lesson I Taught: Lab School Teaching Packageapi-525572712No ratings yet

- ASSESSMENT 2: Project: Mild To Moderate ASDDocument6 pagesASSESSMENT 2: Project: Mild To Moderate ASDapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Scanned With CamscannerDocument2 pagesScanned With Camscannerapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Weeks 6 - 8 Term 3 Mathematics Topic: ChanceDocument8 pagesWeeks 6 - 8 Term 3 Mathematics Topic: Chanceapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Unit Planner: Use Comprehension Strategies To Build Literal and Inferred MeaningDocument3 pagesUnit Planner: Use Comprehension Strategies To Build Literal and Inferred Meaningapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Legislative Requirements That Support Participation and Learning of Students With DisabilityDocument2 pagesLegislative Requirements That Support Participation and Learning of Students With Disabilityapi-525572712No ratings yet

- Ptep Goals-AlgDocument4 pagesPtep Goals-Algapi-316781445No ratings yet

- MemoDocument3 pagesMemoTinker FeiNo ratings yet

- Approaching Children with Special Needs in Primary ELTDocument9 pagesApproaching Children with Special Needs in Primary ELTSavithri SaviNo ratings yet

- Thought Leader in Education DRDocument11 pagesThought Leader in Education DRapi-659774512No ratings yet

- Why American Students Haven't Gotten Better at Reading in 20 Years (The Atlantic)Document4 pagesWhy American Students Haven't Gotten Better at Reading in 20 Years (The Atlantic)fgarlaschelliNo ratings yet

- Understanding Racism & Retention: The Crisis in Black Male High School & College Drop-OutDocument4 pagesUnderstanding Racism & Retention: The Crisis in Black Male High School & College Drop-OutAndrae GenusNo ratings yet

- Telangana SCERT B.ed English Subject TextbookDocument202 pagesTelangana SCERT B.ed English Subject Textbookbeautifullife never giveupNo ratings yet

- EEI Lesson Plan Template: Vital InformationDocument2 pagesEEI Lesson Plan Template: Vital Informationapi-407270738No ratings yet

- English Teaching ProfessionalDocument72 pagesEnglish Teaching ProfessionalDanielle SoaresNo ratings yet

- Educational Policy Outlook JapanDocument24 pagesEducational Policy Outlook JapanJosé Felipe OteroNo ratings yet

- Writing Extraordinary EssaysDocument160 pagesWriting Extraordinary EssaysJulia Shatravenko-Sokolovych100% (3)

- Quality of Good Teach e 2Document24 pagesQuality of Good Teach e 2JayCesarNo ratings yet

- Our Discovery Island 1 TBDocument214 pagesOur Discovery Island 1 TBgaga1979No ratings yet

- Document 2Document1 pageDocument 2api-389627544No ratings yet

- Teacher Resume - Manya BhardwajDocument2 pagesTeacher Resume - Manya BhardwajAniket YadavNo ratings yet

- Maple Bear Franchise OpportunityDocument9 pagesMaple Bear Franchise OpportunityRishi kesh MukherjeeNo ratings yet

- Republic Act No. 7836 Philippine Teachers Professionalization Act of 1994Document2 pagesRepublic Act No. 7836 Philippine Teachers Professionalization Act of 1994Hazel Recites BernaldezNo ratings yet

- Models of Classroom Management WordDocument7 pagesModels of Classroom Management Wordapi-246285515No ratings yet

- Q2 Science 3 - Module 2Document22 pagesQ2 Science 3 - Module 2Jea Caderao AlapanNo ratings yet

- Khan Academy Boosts Student PerformanceDocument58 pagesKhan Academy Boosts Student PerformanceChabelita EleazarNo ratings yet

- Ashley Aldrich Resume 2016Document3 pagesAshley Aldrich Resume 2016api-257330283No ratings yet

- Isns ObservationDocument2 pagesIsns Observationapi-458206269No ratings yet

- Esl Lesson PlanningDocument5 pagesEsl Lesson PlanningAlireza MollaiNo ratings yet

- Bryce Pulley ResumeDocument2 pagesBryce Pulley Resumeapi-269480697No ratings yet

- Grade10 Histry TG 2015Document58 pagesGrade10 Histry TG 2015dxindraNo ratings yet

- Soal Reading HortatoryDocument18 pagesSoal Reading HortatorySyamsul ArifinNo ratings yet

- Module 6 - Becoming A Better StudentDocument9 pagesModule 6 - Becoming A Better StudentMichael AngelesNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plans and Lecture NotesDocument5 pagesLesson Plans and Lecture Notesapi-314418210No ratings yet

- How To Prepare A School Library Proposal: A Model PDFDocument6 pagesHow To Prepare A School Library Proposal: A Model PDFAbid HussainNo ratings yet

- The Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityFrom EverandThe Age of Magical Overthinking: Notes on Modern IrrationalityRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (14)

- If I Did It: Confessions of the KillerFrom EverandIf I Did It: Confessions of the KillerRating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (132)

- The Wicked and the Willing: An F/F Gothic Horror Vampire NovelFrom EverandThe Wicked and the Willing: An F/F Gothic Horror Vampire NovelRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (21)

- Briefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndFrom EverandBriefly Perfectly Human: Making an Authentic Life by Getting Real About the EndNo ratings yet

- Why We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityFrom EverandWhy We Die: The New Science of Aging and the Quest for ImmortalityRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2)

- 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedFrom Everand1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed: Revised and UpdatedRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (109)

- Selling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansFrom EverandSelling the Dream: The Billion-Dollar Industry Bankrupting AmericansRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (17)

- Dark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.From EverandDark Psychology & Manipulation: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Behaviour Using Emotional Influence Techniques, Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Speed Reading, and Hypnosis.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (110)

- Hey, Hun: Sales, Sisterhood, Supremacy, and the Other Lies Behind Multilevel MarketingFrom EverandHey, Hun: Sales, Sisterhood, Supremacy, and the Other Lies Behind Multilevel MarketingRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (102)

- Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassFrom EverandTroubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social ClassRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (24)

- The Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical ChurchFrom EverandThe Exvangelicals: Loving, Living, and Leaving the White Evangelical ChurchRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (12)

- Cult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryFrom EverandCult, A Love Story: Ten Years Inside a Canadian Cult and the Subsequent Long Road of RecoveryRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (44)

- The Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveFrom EverandThe Body Is Not an Apology, Second Edition: The Power of Radical Self-LoveRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (365)

- Prisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldFrom EverandPrisoners of Geography: Ten Maps That Explain Everything About the WorldRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1143)

- Never Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsFrom EverandNever Chase Men Again: 38 Dating Secrets to Get the Guy, Keep Him Interested, and Prevent Dead-End RelationshipsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (386)

- The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionFrom EverandThe Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of EvolutionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (811)

- His Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsFrom EverandHis Needs, Her Needs: Building a Marriage That LastsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (100)

- Dark Psychology: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Manipulation Using Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Mind Control, Subliminal Persuasion, Hypnosis, and Speed Reading Techniques.From EverandDark Psychology: Discover How To Analyze People and Master Human Manipulation Using Body Language Secrets, Covert NLP, Mind Control, Subliminal Persuasion, Hypnosis, and Speed Reading Techniques.Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (88)

- American Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the PuritansFrom EverandAmerican Jezebel: The Uncommon Life of Anne Hutchinson, the Woman Who Defied the PuritansRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (66)

- Cold-Blooded: A True Story of Love, Lies, Greed, and MurderFrom EverandCold-Blooded: A True Story of Love, Lies, Greed, and MurderRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (53)

- The Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great MigrationFrom EverandThe Warmth of Other Suns: The Epic Story of America's Great MigrationRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (1569)

- A New Science of the Afterlife: Space, Time, and the Consciousness CodeFrom EverandA New Science of the Afterlife: Space, Time, and the Consciousness CodeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (5)

- Little Princes: One Man's Promise to Bring Home the Lost Children of NepalFrom EverandLittle Princes: One Man's Promise to Bring Home the Lost Children of NepalNo ratings yet