Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jamasurgery Siam 2017 Oi 170018

Uploaded by

Regine CuntapayOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jamasurgery Siam 2017 Oi 170018

Uploaded by

Regine CuntapayCopyright:

Available Formats

Research

JAMA Surgery | Original Investigation

Comparison of Appendectomy Outcomes Between Senior

General Surgeons and General Surgery Residents

Baha Siam, MD; Abbas Al-Kurd, MD; Natalia Simanovsky, MD; Haitham Awesat, MD; Yahav Cohn, BSc;

Brigitte Helou, MD; Ahmed Eid, MD; Haggi Mazeh, MD

Invited Commentary

IMPORTANCE In some centers, the presence of a senior general surgeon (SGS) is obligatory in page 685

every procedure, including appendectomy, while in others it is not. There is a relative paucity

in the literature of reports comparing the outcomes of appendectomies performed by

unsupervised general surgery residents (GSRs) with those performed in the presence of an

SGS.

OBJECTIVE To compare the outcomes of appendectomies performed by SGSs with those

performed by GSRs.

DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS A retrospective analysis was performed of all patients

16 years or older operated on for assumed acute appendicitis between January 1, 2008, and

December 31, 2015. The cohort study compared appendectomies performed by SGSs and

GSRs in the general surgical department of a teaching hospital.

MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES The primary outcome measured was the postoperative

early and late complication rates. Secondary outcomes included time from emergency

department to operating room, length of surgery, surgical technique (open or laparoscopic),

use of laparoscopic staplers, and overall duration of postoperative antibiotic treatment.

RESULTS Among 1649 appendectomy procedures (mean [SD] patient age, 33.7 [13.3] years;

612 female [37.1%]), 1101 were performed by SGSs and 548 by GSRs. Analysis demonstrated

no significant difference between the SGS group and the GSR group in overall postoperative

early and late complication rates, the use of imaging techniques, time from emergency

department to operating room, percentage of complicated appendicitis, postoperative length

of hospital stay, and overall duration of postoperative antibiotic treatment. However, length

of surgery was significantly shorter in the SGS group than in the GSR group (mean [SD], 39.9

[20.9] vs 48.6 [20.2] minutes; P < .001).

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE This study demonstrates that unsupervised surgical residents

may safely perform appendectomies, with no difference in postoperative early and late

complication rates compared with those performed in the presence of an SGS.

Author Affiliations: Department of

Surgery, Hadassah-Hebrew

University Medical Center, Jerusalem,

Israel (Siam, Al-Kurd, Awesat, Cohn,

Helou, Eid, Mazeh); Department of

Radiology, Hadassah-Hebrew

University Medical Center, Jerusalem,

Israel (Simanovsky).

Corresponding Author: Haggi

Mazeh, MD, Department of Surgery,

Hadassah-Hebrew University Medical

Center, Mount Scopus, PO Box

JAMA Surg. 2017;152(7):679-685. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0578 24035, Jerusalem 91240, Israel

Published online April 19, 2017. (hmazeh@hadassah.org.il).

(Reprinted) 679

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/20/2020

Research Original Investigation Appendectomy by Senior General Surgeons vs General Surgery Residents

A

cute appendicitis is one of the most common causes

of acute abdomen in the surgical profession, and the Key Points

preferred method of treatment is appendectomy.1,2 As

Question Is it safe practice for general surgery residents to

a result, appendectomy (open or laparoscopic) is one of the perform appendectomies alone?

most frequent emergency surgical procedures, and more than

Findings This cohort study included 1649 emergency

300 000 appendectomies are performed annually in the United

appendectomies and compared outcomes of appendectomies

States.3

performed by senior general surgeons with those performed by

Given that appendectomy is a common surgical proce- general surgery residents. Analysis demonstrated no significant

dure, residents are exposed to a large number of appendec- difference in the postoperative early and late complication rates,

tomy procedures early in their surgical training.4-6 This fre- postoperative length of hospital stay, and overall duration of

quency makes it an ideal procedure for junior residents to antibiotic treatment.

perform under the guidance of more experienced senior sur- Meaning The results indicate that residents may safely perform

gical residents. Nevertheless, the level of independence given appendectomies without the presence of a senior general

to general surgery residents (GSRs) performing appendecto- surgeon.

mies varies dramatically between institutions nationwide and

worldwide.7-9

A surgeon’s experience has been shown to improve out- sent was waived by the committee because of the retrospec-

comes in several procedures, such as esophagectomy, pan- tive nature of the data collection.

creatoduodenectomy, thyroidectomy, and other complex op- Between 2008 and 2012, a substantial proportion of the

erations. However, there is a paucity of literature regarding the appendectomies were performed by GSRs without the pres-

effect of surgeon experience on appendectomy outcome.10-13 ence of an SGS. Appendectomies performed during this pe-

In a 2013 study published from our institution, Mizrahi et al14 riod in the presence of an SGS were those performed during

compared pediatric appendectomies performed by GSRs with the morning hours or those performed at night when an SGS

those performed by senior pediatric surgeons, showing a shorter happened to be present in the hospital premises. As a general

time from emergency department (ED) to operating room (OR) rule, all other appendectomies were performed by GSRs alone.

and a shorter length of hospital stay for the residents’ patients, After 2012, all of the appendectomies were performed by an

with no significant difference in the postoperative early and late SGS or by a GSR under the supervision of an SGS (Figure).

complication rates or the readmission rate. A retrospective analy- Relevant data were collected from our medical records.

sis by Graat et al15 of 1538 appendectomy patients demon- Information reviewed included patient age and sex, initial

strated that it is safe for surgical residents to perform appen- symptoms, duration of symptoms, body temperature, heart

dectomies, with no increase in complications or negative effect rate, abdominal physical examination findings, white blood

on quality of care. In a multicenter, prospective study by Singh cell (WBC) count, imaging studies performed, and the opera-

et al16 evaluating 2867 appendectomy cases, no additional tive and postoperative course.

patient risk was demonstrated when the operation was per- The primary outcome measured was the postoperative

formed by an unsupervised surgical resident compared with early and late complication rates. All complications were sub-

operations performed by attendings. graded according to the Clavien-Dindo classification system.

In general, at our institution before 2012, surgical resi- Secondary outcomes included time from ED to OR, length of

dents were allowed to perform appendectomy operations surgery, surgical technique (open or laparoscopic), use of lapa-

without the presence of senior general surgeons (SGSs). After roscopic staplers, and duration of postoperative antibiotic treat-

2012, the policy changed to require the presence of an SGS in ment during hospitalization and after discharge.

all appendectomy cases. This unique change at a specific time

point provided the opportunity to compare the outcomes of

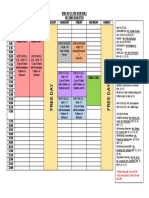

Figure. Study Flowchart

operations performed during the 2 different periods. The ob-

jective of this study was to compare the outcomes of appen-

1860 Appendectomies between

dectomies performed by SGSs with those performed by GSRs. 2008-2015

211 Excluded (interval or incidental

appendectomies)

Methods

A retrospective analysis was performed of appendectomy cases 1649 Included in study

performed at our institution between January 1, 2008, and De-

cember 31, 2015. Inclusion criteria were all emergency appen-

dectomies for assumed acute appendicitis in patients 16 years 931 Appendectomies between 718 Appendectomies between

2008-2012 2012-2015 performed

or older. Patients who underwent elective (interval) appen- 548 Performed by GSR by SGS or by GSR under

383 Performed by GSR supervision of SGS

dectomy or incidental appendectomy as part of gynecologic

in presence of SGS

or oncologic operations were excluded from our analysis. The

study was approved by our institution’s institutional review

GSR indicates general surgery resident; SGS, senior general surgeon.

board committee. The necessity for patient informed con-

680 JAMA Surgery July 2017 Volume 152, Number 7 (Reprinted) jamasurgery.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/20/2020

Appendectomy by Senior General Surgeons vs General Surgery Residents Original Investigation Research

Table 1. Comparison of Preoperative Presentation and Operative Course Between the 2 Study Groups

SGSs GSRs

Variable (n = 1101) (n = 548) P Value

Age, mean (SD), y 35.3 (13.4) 32.9 (12.8) <.001

Female, No. (%) 407 (37.0) 205 (37.4) .21

Duration of symptoms, mean (SD), h 29.4 (57.1) 27.9 (30.8) .57

Alvarado score out of 10, mean (SD) 6.1 (1.5) 6.1 (1.6) .79

Body temperature, mean (SD), °C 36.6 (0.5) 36.6 (0.5) .97

Heart rate, mean (SD), beats/min 84.6 (16) 83.8 (16) .32

WBC count, mean (SD), /μL 13 600 (5461.8) 13 500 (4550.9) .56

Imaging studies performed, No. (%)

US 610 (55.4) 301 (54.9) .81

CT 697 (63.3) 322 (58.8) .09

US and CT 207 (18.8) 77 (14.1) .02

Time from ED to OR, mean (SD), h 10.0 (6.6) 9.6 (8.9) .26 Abbreviations: CT, computed

tomography; ED, emergency

Length of surgery, mean (SD), min 39.9 (20.9) 48.6 (20.2) <.001

department; GSRs, general surgery

Complicated appendicitis, No. (%) 127 (11.5) 69 (12.6) .53 residents; OR, operating room;

Normal appendix, No. (%) 28 (2.5) 20 (3.6) .21 SGSs, senior general surgeons; US,

Laparoscopic appendectomy, No. (%) 1055 (95.8) 493 (90.0) <.001 ultrasonography; WBC, white blood

cell.

Conversion to open surgery, No. (%) 2 (0.2) 0 .31

SI conversion factor: To convert WBC

Use of laparoscopic staplers, No. (%) 149 (13.5) 11 (2.0) <.001

count to ×109/L, multiply by 0.001.

Table 2. Comparison of Postoperative Course Between the 2 Study Groups

SGSs GSRs

Variable (n = 1101) (n = 548) P Value

Postoperative length of hospital stay, mean (SD), d 3.1 (1.8) 3.1 (1.6) .59

Overall duration of postoperative antibiotic treatment, mean (SD), d 3.4 (2.5) 3.5 (2.5) .24 Abbreviations: GSRs, general surgery

residents; SGSs, senior general

Additional home antibiotic treatment, No. (%) 168 (15.3) 119 (21.7) .002

surgeons.

To identify differences between the 2 study groups (SGS A comparison of both groups’ baseline variables identified

vs GSR), univariate analysis with χ2 test and t test was used. that patients in the GSR group were significantly younger than

Statistical calculations were performed using a software pro- those in the SGS group (mean [SD] age, 32.9 [12.8] vs 35.3 [13.4]

gram (SPSS, version 20; SPSS, Inc), and P < .05 was consid- years; P < .001) (Table 1). All other baseline and preoperative

ered statistically significant for all comparisons. Data are variables were similar for both groups. The diagnosis of acute

presented as the median or the mean (SD), as appropriate. appendicitis was confirmed by ultrasound, computed tomog-

raphy, or both in all patients, except for 3 patients who were

taken to surgery with no preoperative imaging. The utility of pre-

operative imaging studies and their influence on decision mak-

Results ing did not differ between the groups.

During the study period, 1860 appendectomies were per- Table 1 summarizes the preoperative and operative courses

formed on patients 16 years or older (Figure). After exclusion of both study groups. No significant difference was found in

of interval or incidental appendectomies, 1649 patients were time from ED to OR in the SGS group vs the GSR group (mean

included in the study. Of the entire cohort included, 1101 ap- [SD], 10.0 [6.6] vs 9.6 [8.9] hours; P = .26). Analysis of the op-

pendectomies were performed by SGSs and 548 appendecto- erative course showed similar percentages of complicated ap-

mies were performed by GSRs. pendicitis (ie, perforated or gangrenous) (11.5% in the SGS group

Analysis of the entire cohort of 1649 patients identified a vs 12.6% in the GSR group, P = .53). However, the mean (SD)

mean (SD) age of 33.7 (13.3) years, with 612 patients (37.1%) length of surgery was significantly shorter in the SGS group

being female. The median Alvarado score at presentation was (39.9 [20.9] minutes) compared with the GSR group (48.6 [20.2]

6 (range, 1-10). The mean (SD) WBC count on presentation was minutes) (P < .001).

13 500 (4800) /μL (to convert WBC count to ×109/L, multiply Analysis of the patients’ postoperative course demon-

by 0.001), and the mean (SD) duration of symptoms before pre- strated no significant difference in the postoperative length of

sentation to the ED was 29.0 (49.9) hours. The mean (SD) time hospital stay or overall duration of postoperative antibiotic

from ED to OR was 9.9 (7.4) hours. One hundred patients (6.1%) treatment between the 2 study groups. However, SGSs

underwent an open appendectomy, and the remainder of the prescribed additional home antibiotic treatment in fewer pa-

patients underwent a laparoscopic appendectomy, with 2 con- tients than GSRs (15.3% vs 21.7%, P = .002) (Table 2).

versions to open surgery. The mean (SD) length of surgery was The postoperative early and late complication rates were

42.8 (20.9) minutes, and the mean (SD) postoperative length similar between the 2 study groups (Table 3). On subgrading

of hospital stay was 3.1 (1.8) days. the complications according to the Clavien-Dindo classifica-

jamasurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Surgery July 2017 Volume 152, Number 7 681

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/20/2020

Research Original Investigation Appendectomy by Senior General Surgeons vs General Surgery Residents

Table 3. Comparison of Postoperative Complications Between the 2 Study Groups

No. (%)

SGSs GSRs

Type of Complication (n = 1101) (n = 548) P Value

Return to the ED 75 (6.8) 43 (7.8) .44

Readmission 41 (3.7) 27 (4.9) .24

Superficial SSI 36 (3.3) 22 (4.0) .43

Deep SSI 13 (1.2) 7 (1.3) .86

Bowel injury 1 (0.1) 1 (0.2) .61

Stump leak 0 1 (0.2) .15 Abbreviations: ED, emergency

Bladder injury 1 (0.1) 2 (0.4) .22 department; GSRs, general surgery

residents; SGSs, senior general

Reoperation 5 (0.5) 4 (0.7) .47

surgeons; SSI, surgical site infection.

tion system, no statistically significant differences were ob- the adverse event rate in the first 30 postoperative days. In mul-

served between the groups. tivariate analysis, patients operated on by senior residents were

found to have slightly lower 30-day adverse events rates, al-

though this finding did not reach statistical significance. In con-

trast, junior residents were found to have outcomes similar to

Discussion those of attendings.

Learning to perform an appendectomy is an integral part of any Mizrahi et al14 compared 246 pediatric appendectomy pa-

surgical resident’s training, providing the resident with basic tients operated on by GSRs with 157 similar cases performed

skills of open and laparoscopic surgery. At some hospitals, a by attending pediatric surgeons. A significantly shorter ED to

board-certified surgeon attends all cases and assists the ju- OR time was demonstrated when patients were operated on

nior resident, while at others a more senior GSR suffices. Con- by surgical residents compared with attending pediatric sur-

cerns about patient outcomes have led some training pro- geons, while our study found no such difference between the

grams, including ours, to determine that appendectomy should SGS and GSR groups. Graat et al15 also observed no significant

routinely be performed under the guidance of an SGS. The difference in ED to OR time between similar studied groups.

present study represents one of the largest available cohorts In contrast to the series by Mizrahi et al,14 which showed

of appendectomy patients in which a comparison is per- a length of surgery 6 minutes shorter for appendectomies per-

formed between those operated on by a GSR alone with those formed by GSRs compared with attending pediatric sur-

operated on in the presence of an SGS. Other than a shorter geons, our study demonstrated that surgical procedures were

length of surgery for the SGS group, no significant differ- almost 9 minutes longer in the GSR group. Although there are

ences were identified between the groups. several possible explanations, this result is likely because of

Few publications have evaluated outcomes of appendec- the advanced experience of our SGSs in laparoscopic surgery.

tomy cases operated on by residents and compared them with Although Graat et al15 found no difference in operative times

those operated on by SGSs. The largest cohort to date was pub- between the studied groups, Fahrner and Schöb17 demon-

lished by Singh et al16 and included 2867 appendectomy cases, strated results similar to ours, with a longer operative time (by

of which 87% were performed by residents and 72% by unsu- 8 minutes) in the resident group compared with the attend-

pervised residents. Graat et al15 (reporting on 1538 appendec- ing surgeon group.15,17 Among the cohort of patients in the

tomy patients) and Fahrner and Schöb17 (reporting on 1197 ap- study by Singh et al,16 junior residents had a significantly larger

pendectomy patients) published studies with similar findings. proportion of operations lasting more than 60 minutes, when

Mizrahi et al14 evaluated appendectomies in 403 pediatric pa- compared to senior residents and attendings. It could be ar-

tients and compared the outcomes with those of appendecto- gued that the additional operative time in the resident group

mies performed by GSRs vs SGSs in other studies5,9,15-17 (Table 4). may be related to greater caution because of decreased self-

Our cohort of 1649 patients represents the second largest confidence compared with SGSs. Nevertheless, the some-

of the above-mentioned studies. In the present study, appen- what longer operative time in the present study did not nega-

dectomies by unsupervised GSRs were compared with those tively affect patient outcomes. That said, in an era in which

performed in the presence of an SGS with regard to preopera- patient care expenses are under great scrutiny, the impor-

tive, intraoperative, and postoperative data. Because of the tance of OR costs must always be kept in mind.18 One of many

paucity of studies available in the literature on this topic, we essential components of these costs is length of surgery; there-

believe that our cohort represents an important contribution fore, the significance of a 9-minute difference between SGSs

to the available literature. and GSRs should not be underestimated.19

In the study by Singh et al,16 a total of 2867 appendecto- Our study demonstrated a significantly higher open ap-

mies were prospectively, nonrandomly divided into those per- pendectomy rate in patients operated on by GSRs compared

formed by attendings, by senior surgical residents, and by ju- with those operated on by SGSs (10.0% [55 of 548] vs 4.2% [46

nior residents, with 72% of the residents’ operations performed of 1101], P < .001). However, it must be emphasized that be-

without supervision of an attending. The primary outcome was fore 2012 open appendectomy was a more common practice.

682 JAMA Surgery July 2017 Volume 152, Number 7 (Reprinted) jamasurgery.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/20/2020

Appendectomy by Senior General Surgeons vs General Surgery Residents Original Investigation Research

Table 4. Summary of Previous Publications Comparing Appendectomy Outcomes Between SGSs and GSRs

Length of Surgery, Mean

Source No. of Patients (SD), mina P Value Complication Rate, % P Value

Shabtai et al,5 2004 (n = 341) Comparing J vs S Residentsb

Laparoscopic 5 J + J 96 (22.8) J + J

appendectomy

79 J + S 84 (22.2) J + S .03 NA NA

67 S + J 75 (24) S + J

Open appendectomy 16 J + J 90 (53.4) J + J

122 J + S 84 (37.8) J + S .02 NA NA

52 S + J 51 (27) S + J

Wong et al,9 2007 (n = 344) Comparing UST vs CS

Laparoscopic 92 UST 65 (22) UST 9 UST

appendectomy <.05 .32

45 CS 52 (18) CS 7 CS

Open appendectomy 122 UST 57 (24) UST 12 UST Abbreviations: CS, consultant

<.05 .69 surgeon; GSRs, general surgery

85 CS 48 (21) CS 7 CS residents; J, junior; NA, not

Graat et al,15 2012 (n = 1538) applicable; NS, not significant;

Unsupervised residents 589 50.0 (18.3) 16 S, senior; SGSs, senior general

surgeons; UST, unsupervised surgical

Supervised residents 597 49.5 (18.7) .02 17 NS trainee.

Surgeons 352 46.7 (17.1 20 a

The numbers in Singh et al16 refer to

Fahrner and Schöb,17 2012 (n = 1197) the percentage of operations with a

Resident surgeons 684 61.34 (25.7) 1.8 duration >60 minutes. Values of the

.0001 .04 exact length of operation were not

Attending surgeons 513 53.65 (29.9) 3.7 presented in the article.

Mizrahi et al,14 2013 (n = 403) b

J + J indicates junior residents

GSRs 246 54 (1.5) 5 operate with the assistance of

.01 .29 another junior resident, J + S

Pediatric surgeons 157 60 (2.1) 7

indicates junior residents operate

Singh et al,16 2014 (n = 2867)c with the assistance of a senior

Junior residents 1183 53.4 13.3 resident, and S + J indicates senior

residents operate with the

Senior residents 1301 48.3 .01 11.8 .53

assistance of junior residents.

Attendings 367 48.4 16.9 c

No documentation of primary

Present Study (n = 1649) operator was identified for 16

GSRs 548 48.6 (20.2) 9.7 patients. For length of surgery,

<.0001 .22 mean and SD values were not

SGSs 1101 39.9 (20.9) 7.9

available.

In an analysis of the subgroup of surgical procedures per- While other studies14,15 have demonstrated that SGSs pre-

formed by SGSs before 2012 (n = 383), an open appendec- scribed more in-hospital parenteral antibiotic treatment than

tomy rate of 9.4% (n = 36) was demonstrated. Therefore, it surgical residents, the overall duration of postoperative anti-

seems that this finding reflects a historical difference rather biotic treatment before discharge in our cohort was similar be-

than a true variation between the 2 groups. tween the 2 groups. In contrast, GSRs prescribed additional

In our cohort, there was no statistically significant differ- home antibiotic treatment more often than SGSs (15.3% vs

ence in postoperative early and late complication rates be- 21.7%); however, similar to the occurrence of open appendec-

tween patients operated on by GSRs and those operated by tomy, we hypothesize that this finding represents a historical

SGSs. Graat et al15 divided appendectomies performed at their variation rather than a true difference between the SGS and

institution into the following 3 groups: appendectomies per- GSR groups. On analysis of the subgroup of patients operated

formed by surgeons alone, appendectomies performed by resi- on by SGSs before 2012 (n = 383), a 23.8% (n = 91) rate of ad-

dents under surgeon supervision, and appendectomies per- ditional home antibiotic treatment was found, which is higher

formed by residents alone. Among the 1538 patients analyzed, than that in the resident group, although not statistically sig-

no difference was demonstrated in overall complication or mor- nificant. We assume that this historical variation is because of

tality rates between the 3 groups. Mizrahi et al14 demon- the increased adherence to guidelines regarding postopera-

strated similar results, with no significant difference in com- tive antibiotic use in more recent years.

plication rates between the groups. Although Fahrner and In our cohort of appendectomy cases, a normal appendix

Schöb17 observed no significant difference in intraoperative was found on postoperative pathological examination in 48 pa-

complication rates between GSRs and SGSs in their 1197 pa- tients (2.9%), with no significant variation between those op-

tients analyzed, they found higher 30-day morbidity (3.7% vs erated on by GSRs vs SGSs (Table 1). Mizrahi et al14 demon-

1.8%, P = .04) and greater need for surgical reintervention (2.5% strated similar findings, with a normal appendix rate of 4.5%

vs 0.6%, P = .005) in the SGS group. and no significant difference between GSRs and pediatric

jamasurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Surgery July 2017 Volume 152, Number 7 683

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/20/2020

Research Original Investigation Appendectomy by Senior General Surgeons vs General Surgery Residents

surgeons. In contrast, Graat et al15 found a 6% rate of clini- tial proportion of the SGS group patients were operated on in

cally (but not histologically shown) normal appendix, with a recent years, presents an obvious historical bias. Therefore,

higher prevalence of normal appendix among the SGS group. variability in common practices between the 2 periods may

Singh et al16 observed no significant difference in the normal have affected the observed results. In addition, the level of in-

(histologically shown) appendix rate between attendings and volvement of the surgical resident in surgical procedures per-

junior or senior residents; however, an overall normal appen- formed in the presence of an SGS cannot be determined by the

dix rate of 20.2% was recorded. records available. It is clear to any individual who has worked

The modern-day general surgical residency has evolved in in the OR that this involvement can vary greatly, ranging from

light of demands for higher levels of supervision. This require- cases in which the resident minimally participates in the op-

ment results in less resident autonomy and a lower level of se- eration to cases in which the resident performs the entire op-

nior resident self-confidence.20 Giving a resident a certain level eration almost single-handedly under the guidance of the SGS.

of independence in patient care can provide him or her with Randomized trials are needed to obtain more accurate re-

important tools needed to develop into an effective senior sur- sults.

geon. The publications reviewed herein, as well as the pre-

sent study, have shown no negative influence on patient safety

in appendectomy cases performed by residents. This safety has

also been demonstrated for other minor surgical procedures.21

Conclusions

Therefore, the question posed is whether the inherent edu- The results of this study suggest that the absence of an SGS in

cational value of appendectomies can be used as a model for the OR during appendectomies does not seem to negatively

providing resident autonomy, while maintaining patient safety affect patient outcomes. Therefore, we conclude that under stan-

and outcomes. dard conditions more experienced surgical residents can be al-

lowed to perform appendectomies alone. Residents perform-

Limitations ing unsupervised appendectomies should be able to recognize

Our study has several limitations. The fact that all of the GSR clinical and intraoperative circumstances that necessitate re-

group patients were operated on before 2012, while a substan- questing the assistance of a more experienced senior surgeon.

ARTICLE INFORMATION 4. Richards MK, McAteer JP, Drake FT, Goldin AB, patient outcomes? a study of major pancreatic

Accepted for Publication: January 20, 2017. Khandelwal S, Gow KW. A national review of the resections in California. Surgery. 2000;128(2):286-

frequency of minimally invasive surgery among 292.

Published Online: April 19, 2017. general surgery residents: assessment of ACGME

doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0578 12. Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney

case logs during 2 decades of general surgery PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and

Author Contributions: Drs Siam and Mazeh had resident training. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(2):169-172. operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med.

full access to all the data in the study and take 5. Shabtai M, Rosin D, Zmora O, et al. The impact of 2003;349(22):2117-2127.

responsibility for the integrity of the data and the a resident’s seniority on operative time and length

accuracy of the data analysis. 13. Sosa JA, Bowman HM, Tielsch JM, Powe NR,

of hospital stay for laparoscopic appendectomy: Gordon TA, Udelsman R. The importance of

Study concept and design: Siam, Al-Kurd, Cohn, Eid, outcomes used to measure the resident’s

Mazeh. surgeon experience for clinical and economic

laparoscopic skills. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(9):1328- outcomes from thyroidectomy. Ann Surg. 1998;228

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All 1330.

authors. (3):320-330.

Drafting of the manuscript: Siam, Al-Kurd, Awesat, 6. Malangoni MA, Biester TW, Jones AT, 14. Mizrahi I, Mazeh H, Levy Y, et al. Comparison of

Cohn, Eid, Mazeh. Klingensmith ME, Lewis FR Jr. Operative experience pediatric appendectomy outcomes between

Critical revision of the manuscript for important of surgery residents: trends and challenges. J Surg pediatric surgeons and general surgery residents.

intellectual content: Siam, Al-Kurd, Simanovsky, Educ. 2013;70(6):783-788. J Surg Res. 2013;180(2):185-190.

Cohn, Helou, Mazeh. 7. Somme S, To T, Langer JC. Effect of subspecialty 15. Graat LJ, Bosma E, Roukema JA, Heisterkamp J.

Statistical analysis: Siam, Al-Kurd, Awesat, Cohn, training on outcome after pediatric appendectomy. Appendectomy by residents is safe and not

Mazeh. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(1):221-226. associated with a higher incidence of

Administrative, technical, or material support: Siam, 8. Whisker L, Luke D, Hendrickse C, Bowley DM, complications: a retrospective cohort study. Ann Surg.

Helou. Lander A. Appendicitis in children: a comparative 2012;255(4):715-719.

Study supervision: Siam, Al-Kurd, Eid, Mazeh. study between a specialist paediatric centre and a 16. Singh P, Turner EJ, Cornish J, Bhangu A;

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported. district general hospital. J Pediatr Surg. 2009;44 National Surgical Research Collaborative. Safety

(2):362-367. assessment of resident grade and supervision level

REFERENCES 9. Wong K, Duncan T, Pearson A. Unsupervised during emergency appendectomy: analysis of a

1. Stewart B, Khanduri P, McCord C, et al. Global laparoscopic appendicectomy by surgical trainees is multicenter, prospective study. Surgery. 2014;156

disease burden of conditions requiring emergency safe and time-effective. Asian J Surg. 2007;30(3): (1):28-38.

surgery. Br J Surg. 2014;101(1):e9-e22. 161-166. 17. Fahrner R, Schöb O. Laparoscopic

2. Bhangu A, Søreide K, Di Saverio S, Assarsson JH, 10. Hwang CS, Pagano CR, Wichterman KA, appendectomy as a teaching procedure:

Drake FT. Acute appendicitis: modern Dunnington GL, Alfrey EJ. Resident versus no experiences with 1,197 patients in a community

understanding of pathogenesis, diagnosis, and resident: a single institutional study on operative hospital. Surg Today. 2012;42(12):1165-1169.

management. Lancet. 2015;386(10000):1278-1287. complications, mortality, and cost. Surgery. 2008; 18. Zygourakis CC, Valencia V, Moriates C, et al.

3. Wu JX, Dawes AJ, Sacks GD, Brunicardi FC, 144(2):339-344. Association between surgeon scorecard use and

Keeler EB. Cost effectiveness of nonoperative 11. Hutter MM, Glasgow RE, Mulvihill SJ. Does the operating room costs. JAMA Surg. Published online

management versus laparoscopic appendectomy participation of a surgical trainee adversely impact December 7, 2016.

for acute uncomplicated appendicitis. Surgery.

2015;158(3):712-721.

684 JAMA Surgery July 2017 Volume 152, Number 7 (Reprinted) jamasurgery.com

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/20/2020

Appendectomy by Senior General Surgeons vs General Surgery Residents Original Investigation Research

19. Fong AJ, Smith M, Langerman A. Efficiency for fellowship: results of a survey of fellowship safely increase operative autonomy. J Surg Educ.

improvement in the operating room. J Surg Res. program directors. Ann Surg. 2013;258(3):440-449. 2016;73(6):e142-e149.

2016;204(2):371-383. 21. Wojcik BM, Fong ZV, Patel MS, et al. The

20. Mattar SG, Alseidi AA, Jones DB, et al. General resident-run minor surgery clinic: a pilot study to

surgery residency inadequately prepares trainees

Invited Commentary

Increasing Resident Autonomy Without Compromising

Patient Safety

Rebecca L. Gunter, MD; Jacob A. Greenberg, MD, EdM

General surgery residency training has undergone signifi- risk adjustment of outcomes. Larger analyses of American Col-

cant changes in recent years, resulting in part from increased lege of Surgery National Surgical Quality Improvement Pro-

resident duty-hour restrictions and mandated attending su- gram data have yielded similar results in terms of increased

pervision in the operating operative time when residents participate in operations and

room, which ostensibly stem either decreased or equivalent postoperative mortality.2 How-

Related article page 679 from concerns regarding pa- ever, there may be a trend toward increased rates of post-

tient safety. However, the operative morbidity, particularly in the case of surgical site

mandate to train future generations of surgeons remains, thus infections.3,4

creating an inherent tension between patient safety and op- The potential detrimental influence on patient outcomes

portunities for resident autonomy and independent decision seen when residents participate must be balanced against the

making. educational needs of residents and the resources required to

In this issue of JAMA Surgery, Siam et al1 present the out- train them for independent practice. Fellowship directors have

comes of appendectomies performed at their institution in the reported limited operative proficiency among their incoming

period before and after mandated attending presence at all op- fellows, signaling that general surgery residency has not ad-

erations. The authors are to be congratulated for taking advan- equately prepared them for the next step in training, likely be-

tage of this natural experiment to examine the influence of resi- cause of insufficient opportunities to practice and develop their

dent independence on patient outcomes. They found no skills.5 They also note that simulation alone is unlikely to com-

significant difference in patient morbidity or mortality and no pensate for this lack of real-life experience. Although valid, con-

difference in markers of decision making, such as preopera- cerns over patient safety and operating room efficiency should

tive tests ordered or time from emergency department to op- not overshadow the need for surgical residents to hone their

erating room, when a general surgery resident worked inde- craft. In addition, the increased time required for resident edu-

pendently or under the supervision of an attending surgeon. The cation should perhaps be accounted for in funding models at

only significant difference was in operative time, with resi- teaching institutions.6

dents operating independently requiring a mean of almost 9 As surgical residency training moves toward milestone and

more minutes to complete the operation than when an attend- competency–based training, the work by Siam et al1 is an im-

ing surgeon was present. portant contribution for delineating which operations can be

As the authors note, 1 this investigation is a single- safely performed independently by residents. Appendectomy

institution study examining a sole operation, as are the stud- and procedures of similar complexity can and should be used

ies against which they have compared their results, with no to facilitate increased resident autonomy and confidence.

ARTICLE INFORMATION REFERENCES 4. Castleberry AW, Clary BM, Migaly J, et al.

Author Affiliations: Department of Surgery, 1. Siam B, Al-Kurd A, Simanovsky N, et al. Resident education in the era of patient safety:

University of Wisconsin, Madison. Comparison of appendectomy outcomes between a nationwide analysis of outcomes and

senior general surgeons and general surgery complications in resident-assisted oncologic

Corresponding Author: Jacob A. Greenberg, MD, surgery. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20(12):3715-3724.

EdM, Department of Surgery, University of residents [published online April 19, 2017]. JAMA

Wisconsin, 600 Highland Ave, Mail Code 7375, Surg. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0578 5. Mattar SG, Alseidi AA, Jones DB, et al. General

Madison, WI 53792 (greenbergj@surgery.wisc 2. Tseng WH, Jin L, Canter RJ, et al. Surgical surgery residency inadequately prepares trainees

.edu). resident involvement is safe for common elective for fellowship: results of a survey of fellowship

general surgery procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2011; program directors. Ann Surg. 2013;258(3):440-449.

Published Online: April 19, 2017.

doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2017.0582 213(1):19-26. 6. Vinden C, Malthaner R, McGee J, et al. Teaching

3. Scarborough JE, Bennett KM, Pappas TN. surgery takes time: the impact of surgical education

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: None reported. on time in the operating room. Can J Surg. 2016;59

Defining the impact of resident participation on

outcomes after appendectomy. Ann Surg. 2012;255 (2):87-92.

(3):577-582.

jamasurgery.com (Reprinted) JAMA Surgery July 2017 Volume 152, Number 7 685

© 2017 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 10/20/2020

You might also like

- CHN 2 1-7 Formative Quiz #2B - NCM 113 - Community Health Nursing Ii - Population Groups andDocument5 pagesCHN 2 1-7 Formative Quiz #2B - NCM 113 - Community Health Nursing Ii - Population Groups andRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- CHN 2 1-4 FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT #1 - MCQ 15 Items + 5 Points DBP - Week 3 - NCM 113 - COMMUNITY HEALTH NURSING II - POPULATION GROUPS ANDDocument8 pagesCHN 2 1-4 FORMATIVE ASSESSMENT #1 - MCQ 15 Items + 5 Points DBP - Week 3 - NCM 113 - COMMUNITY HEALTH NURSING II - POPULATION GROUPS ANDRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Problem From Philosophy PDFDocument7 pagesChapter 12 Problem From Philosophy PDFRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Assessment of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (Erasâ®) Protocol in Colorectal Cancer SurgeryDocument8 pagesAssessment of Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (Erasâ®) Protocol in Colorectal Cancer SurgeryIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Experience of General Surgery Residents in The Creation of Small Bowel and Colon AnastomosesDocument7 pagesExperience of General Surgery Residents in The Creation of Small Bowel and Colon AnastomosesDiego Andres VasquezNo ratings yet

- The Comparison of Hand-Sewn and Stapled Anastomosis in EsophagectomyDocument4 pagesThe Comparison of Hand-Sewn and Stapled Anastomosis in EsophagectomyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Utilityofimage-Guidance Infrontalsinussurgery: Gretchen M. Oakley,, Henry P. Barham,, Richard J. HarveyDocument14 pagesUtilityofimage-Guidance Infrontalsinussurgery: Gretchen M. Oakley,, Henry P. Barham,, Richard J. HarveyJuan Pablo Mejia BarbosaNo ratings yet

- Fsurg 09 848565Document10 pagesFsurg 09 848565Jairo Farias OrtizNo ratings yet

- Gastrectomía LaparoscópicaDocument7 pagesGastrectomía LaparoscópicaGreyza VelazcoNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Radiology and Imaging Technology Ijrit 5 051Document7 pagesInternational Journal of Radiology and Imaging Technology Ijrit 5 051grace liwantoNo ratings yet

- Alesina Et Al., 2021Document9 pagesAlesina Et Al., 2021NyomantrianaNo ratings yet

- Long-Term Complications of Appendectomy: A Systematic ReviewDocument8 pagesLong-Term Complications of Appendectomy: A Systematic ReviewNurul Mukhlisah IsmailNo ratings yet

- Patient Reported Aesthetic Outcomes of Upper BlephDocument9 pagesPatient Reported Aesthetic Outcomes of Upper BlephRobertoNo ratings yet

- Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and TraumaDocument5 pagesJournal of Clinical Orthopaedics and TraumaGaetano De BiaseNo ratings yet

- E8gklehwg'oirehtgrbjnag,/s" EIDocument6 pagesE8gklehwg'oirehtgrbjnag,/s" EIvenkayammaNo ratings yet

- Fonc 09 00597Document13 pagesFonc 09 00597Giann PersonaNo ratings yet

- With The Advance in The Techniques of Hemostasis Is It Necessary To Use Drain Routinely in Thyroid Surgery A Comparative StudyDocument8 pagesWith The Advance in The Techniques of Hemostasis Is It Necessary To Use Drain Routinely in Thyroid Surgery A Comparative StudyAthenaeum Scientific PublishersNo ratings yet

- Synthetic Versus Biological Mesh in Laparoscopic and Open Ventral Hérnia RepairDocument9 pagesSynthetic Versus Biological Mesh in Laparoscopic and Open Ventral Hérnia RepairRhuan AntonioNo ratings yet

- Julliard Worse Outcomes EVH 2011Document7 pagesJulliard Worse Outcomes EVH 2011Mary MoraNo ratings yet

- A Comparison of The Cost - Utility of Ultrasound-Guided High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound and Hysterectomy For Adenomyosis: A Retrospective StudyDocument6 pagesA Comparison of The Cost - Utility of Ultrasound-Guided High-Intensity Focused Ultrasound and Hysterectomy For Adenomyosis: A Retrospective StudyAgung SentosaNo ratings yet

- Endoscopically Access YANG - TMJ ProsthesisDocument6 pagesEndoscopically Access YANG - TMJ ProsthesisClínica BMFNo ratings yet

- Laparoscopic Vs Open Distal Pancreatectomy: A Single-Institution Comparative StudyDocument6 pagesLaparoscopic Vs Open Distal Pancreatectomy: A Single-Institution Comparative StudyHana YunikoNo ratings yet

- Single Incision Laparoscopic Appendicectomy Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Appendicectomy-A Prospective StudyDocument6 pagesSingle Incision Laparoscopic Appendicectomy Versus Conventional Laparoscopic Appendicectomy-A Prospective StudySabreen SaniaNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S2405857220300218 MainDocument5 pages1 s2.0 S2405857220300218 MainIkea BalhonNo ratings yet

- Comparison PiezoDocument13 pagesComparison PiezoMiguel ChanNo ratings yet

- Dobnig 2020 Austria Thryoid RFA Guidelines s10354-019-0682-2Document9 pagesDobnig 2020 Austria Thryoid RFA Guidelines s10354-019-0682-2E cNo ratings yet

- Serarslan 2017Document5 pagesSerarslan 2017vistamaniacNo ratings yet

- Demographic Condylar HyperplasiaDocument9 pagesDemographic Condylar HyperplasiaLisdany BecerraNo ratings yet

- Iranjradiol 14 03 21742Document5 pagesIranjradiol 14 03 21742AisahNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Analysis of Total Thyroidectomy and Lobectomy As Surgical Approaches in Patients Undergoing Thyroid SurgeryDocument4 pagesA Comparative Analysis of Total Thyroidectomy and Lobectomy As Surgical Approaches in Patients Undergoing Thyroid SurgeryInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Minimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery: A Safe Alternative For Aortic Valve Replacement?Document2 pagesMinimally Invasive Cardiac Surgery: A Safe Alternative For Aortic Valve Replacement?lkulacogluNo ratings yet

- Rajapandian 2018Document5 pagesRajapandian 2018DH SiriruiNo ratings yet

- Surgery For Glaucoma in Patients With Facial Port Wine MarkDocument6 pagesSurgery For Glaucoma in Patients With Facial Port Wine MarkPutri kartiniNo ratings yet

- Degenerative Meniscal Tears (Graaf Et Al 2019)Document7 pagesDegenerative Meniscal Tears (Graaf Et Al 2019)nsboyadzhievNo ratings yet

- 1-S2.0-S0039606022004056-Main 2Document6 pages1-S2.0-S0039606022004056-Main 2alihumoodhasanNo ratings yet

- Biswas2014 PDFDocument7 pagesBiswas2014 PDFDhruv MahajanNo ratings yet

- 10 1016@j Oooo 2020 03 048Document11 pages10 1016@j Oooo 2020 03 048Arthur CésarNo ratings yet

- Advantages and Limitations of Endoscopic Septoplasty Experience of 120 CasesDocument6 pagesAdvantages and Limitations of Endoscopic Septoplasty Experience of 120 CasesInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology100% (1)

- Advantage and Limitation of Endoscopic SepDocument6 pagesAdvantage and Limitation of Endoscopic SepTareq MohammadNo ratings yet

- Comparison of The Short-Term Outcomes of Using DST and PPH Staplers in The Treatment of Grade Iii and Iv HemorrhoidsDocument7 pagesComparison of The Short-Term Outcomes of Using DST and PPH Staplers in The Treatment of Grade Iii and Iv HemorrhoidsdianisaindiraNo ratings yet

- Ejo 1Document11 pagesEjo 1ayisNo ratings yet

- Fabio Febrian JurnalDocument3 pagesFabio Febrian JurnallarasatiNo ratings yet

- RAVARIDocument6 pagesRAVARIGenesis BiceraNo ratings yet

- FVVinObGyn 11 269Document29 pagesFVVinObGyn 11 269Noël ChannetonNo ratings yet

- Review of Surgical Techniques and Guide For Decision Making in The Treatment of Benign Parotid TumorsDocument15 pagesReview of Surgical Techniques and Guide For Decision Making in The Treatment of Benign Parotid Tumors9gps6jw28bNo ratings yet

- Is 9Document9 pagesIs 9intan juitaNo ratings yet

- Single Versus Multi-Incisional Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument12 pagesSingle Versus Multi-Incisional Video-Assisted Thoracic Surgery: A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisHendrikus Surya Adhi PutraNo ratings yet

- Lu 2019Document10 pagesLu 2019CAMILO ANDRÉS SABOGAL ARGUELLONo ratings yet

- International Journal of SurgeryDocument7 pagesInternational Journal of SurgeryJose Manuel Luna VazquezNo ratings yet

- A Prospective Comparativestudy of Open Versus Laparoscopic Appendectomy: A Single Unit StudyDocument8 pagesA Prospective Comparativestudy of Open Versus Laparoscopic Appendectomy: A Single Unit StudyIJAR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Efficacy of EUS-RFA in Pancreatic Tumors: Is It Ready For Prime Time? A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisDocument9 pagesEfficacy of EUS-RFA in Pancreatic Tumors: Is It Ready For Prime Time? A Systematic Review and Meta-AnalysisRadinal MauludiNo ratings yet

- 107 246 1 PBDocument4 pages107 246 1 PBAnjali ThakurNo ratings yet

- Alganabi2021 Article SurgicalSiteInfectionAfterOpenDocument9 pagesAlganabi2021 Article SurgicalSiteInfectionAfterOpenWahyudhy SajaNo ratings yet

- Hypospadias SurveyDocument6 pagesHypospadias SurveyDevi Humairah IrawanNo ratings yet

- Novel Hemostatic Adhesive Powder For Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal BleedingDocument5 pagesNovel Hemostatic Adhesive Powder For Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleedingrahul krishnanNo ratings yet

- Russell 2017Document6 pagesRussell 2017pancholin_9No ratings yet

- Comparison of Costs and Short-Term Clinical Outcomes of Per-Oral Endoscopic Myotomy and Laparoscopic Heller MyotomyDocument6 pagesComparison of Costs and Short-Term Clinical Outcomes of Per-Oral Endoscopic Myotomy and Laparoscopic Heller MyotomyDavids MarinNo ratings yet

- Medicina 59 01545 v2Document6 pagesMedicina 59 01545 v2materthaiNo ratings yet

- Injury: Kiran C. Mahabier, Lucas M.M. Vogels, Bas J. Punt, Gert R. Roukema, Peter Patka, Esther M.M. Van LieshoutDocument4 pagesInjury: Kiran C. Mahabier, Lucas M.M. Vogels, Bas J. Punt, Gert R. Roukema, Peter Patka, Esther M.M. Van LieshoutGabriel GolesteanuNo ratings yet

- Comparison of Long-Term Surgical Outcomes of Two-Muscle Surgery in Basic-Type Intermittent Exotropia: Bilateral Versus UnilateralDocument9 pagesComparison of Long-Term Surgical Outcomes of Two-Muscle Surgery in Basic-Type Intermittent Exotropia: Bilateral Versus UnilateralerwinNo ratings yet

- 11.1 AP Accuracy of Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology FNAC IDocument7 pages11.1 AP Accuracy of Fine Needle Aspiration Cytology FNAC IdrdivyeshgoswamiNo ratings yet

- TMP 99 BADocument6 pagesTMP 99 BAFrontiersNo ratings yet

- The SAGES Manual of Flexible EndoscopyFrom EverandThe SAGES Manual of Flexible EndoscopyPeter NauNo ratings yet

- Thesis 2 (Word)Document209 pagesThesis 2 (Word)Regine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Evidence Based ActivityDocument3 pagesEvidence Based ActivityRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Medical DetectivesDocument2 pagesMedical DetectivesRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Critical Appraisal Checklist For Qualitative ResearchDocument4 pagesCritical Appraisal Checklist For Qualitative ResearchRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Reconceptualising Relatedness in Education in Distanced' TimesDocument16 pagesReconceptualising Relatedness in Education in Distanced' TimesRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- BSN 303 Class Schedule Second Semester: (CE) - NCM 116 (CE) - NCM 116Document1 pageBSN 303 Class Schedule Second Semester: (CE) - NCM 116 (CE) - NCM 116Regine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- NUR 1218 Maladaptive Patterns of Behaviour LECTURE ONLY 2020 2021 - Dec26 - Ver1.0Document2 pagesNUR 1218 Maladaptive Patterns of Behaviour LECTURE ONLY 2020 2021 - Dec26 - Ver1.0Regine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Master Rotation Plan of Level Iii (Areas: Geria, Medical Surgical, Psych Nursing)Document5 pagesMaster Rotation Plan of Level Iii (Areas: Geria, Medical Surgical, Psych Nursing)Regine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Online Learning: A Panacea in The Time of COVID-19 Crisis: Shivangi DhawanDocument18 pagesOnline Learning: A Panacea in The Time of COVID-19 Crisis: Shivangi DhawanRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: International Journal of Educational Research OpenDocument25 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: International Journal of Educational Research OpenRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Review Articles: Acute AppendicitisDocument10 pagesReview Articles: Acute AppendicitisRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Pedia Module Preschooler PDFDocument11 pagesPedia Module Preschooler PDFRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Journal Pre-Proof: International Journal of Educational Research OpenDocument25 pagesJournal Pre-Proof: International Journal of Educational Research OpenRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Teacher Stress Final Pre-Publication DraftDocument18 pagesTeacher Stress Final Pre-Publication DraftRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry ReviewerDocument4 pagesBiochemistry ReviewerRegine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Delicacies Region 6Document2 pagesDelicacies Region 6Regine CuntapayNo ratings yet

- Traditional Open AppendectomyDocument14 pagesTraditional Open AppendectomyBayu NoviandaNo ratings yet

- Pathology of AppendixDocument26 pagesPathology of Appendixnovitafitri123No ratings yet

- The Surgical Examination of ChildrenDocument315 pagesThe Surgical Examination of ChildrenPatricia Beznea100% (1)

- GI Part 2 2016 StudentDocument131 pagesGI Part 2 2016 StudentDaniel RayNo ratings yet

- Appendicitis - ClinicalKeyDocument38 pagesAppendicitis - ClinicalKeyjpma2197No ratings yet

- AppendicitisDocument36 pagesAppendicitisPetro MyronovNo ratings yet

- Acute AppendicitisDocument1 pageAcute AppendicitisAllen AykayNo ratings yet

- 26 Sri Rahayu Oktaviani PDFDocument117 pages26 Sri Rahayu Oktaviani PDFReizhaeNo ratings yet

- PEROTONITISDocument68 pagesPEROTONITISChloie Marie RosalejosNo ratings yet

- Alinsangao, Nashwa N. BSN 3B - SIC (Pathogenesis & Life Threatening Pathways)Document5 pagesAlinsangao, Nashwa N. BSN 3B - SIC (Pathogenesis & Life Threatening Pathways)NASHWA NASLUN. ALINSANGAONo ratings yet

- Imaging in Acute Appendicitis: A Review: RK Jain, M Jain, CL Rajak, S Mukherjee, PP Bhattacharyya, MR ShahDocument10 pagesImaging in Acute Appendicitis: A Review: RK Jain, M Jain, CL Rajak, S Mukherjee, PP Bhattacharyya, MR ShahVidini Kusuma AjiNo ratings yet

- Legal Medicine CasesDocument138 pagesLegal Medicine Casesmuton20No ratings yet

- Abdominal Pains in Children Under 12Document5 pagesAbdominal Pains in Children Under 12clubsanatateNo ratings yet

- IcdDocument21 pagesIcdVicky AprizanoNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis in Adults Diagnostic EvaluationDocument13 pagesAcute Appendicitis in Adults Diagnostic EvaluationjimdioNo ratings yet

- Managing Acute Abdominal Pain in Pediatric Patients: Current PerspectivesDocument9 pagesManaging Acute Abdominal Pain in Pediatric Patients: Current PerspectivesAnonymous h4SCPPayNo ratings yet

- Gastrointestinal PathologyDocument59 pagesGastrointestinal PathologybonadnadineNo ratings yet

- Appendicitis & Appendectomy: Jenny Juniora AjocDocument31 pagesAppendicitis & Appendectomy: Jenny Juniora AjocJenny AjocNo ratings yet

- Test 7: Appendicitis Definition and FactsDocument21 pagesTest 7: Appendicitis Definition and FactsRuhi RuhiNo ratings yet

- Approach To Abdominal PainDocument22 pagesApproach To Abdominal PainOmar AbdillahiNo ratings yet

- Acute Appendicitis: Modern Understanding of Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and ManagementDocument11 pagesAcute Appendicitis: Modern Understanding of Pathogenesis, Diagnosis, and ManagementMishel Rodriguez GuzmanNo ratings yet

- Appendicitis ManuscriptDocument4 pagesAppendicitis Manuscriptkint manlangitNo ratings yet

- Diagnosis and Management of Acute AppendicitisDocument23 pagesDiagnosis and Management of Acute AppendicitisFadhilla R. MeutiaNo ratings yet

- Appendectomy Appendicitis Case Study1Document18 pagesAppendectomy Appendicitis Case Study1Los Devio100% (1)

- Unit - I AuditDocument12 pagesUnit - I AuditNirav BunhaNo ratings yet

- Williams Gynecology PDFDriveDocument25 pagesWilliams Gynecology PDFDriveKawaii Rjen-chanNo ratings yet

- Acute Perforated AppendicitisDocument7 pagesAcute Perforated AppendicitisS3V4_9154No ratings yet

- 3rd Year OSCE StationsDocument6 pages3rd Year OSCE StationsrutendonormamapurisaNo ratings yet

- Medical Surgical Nursing Exams BoardDocument36 pagesMedical Surgical Nursing Exams BoardCINDY� BELMESNo ratings yet

- Görker Sel - Practical Guide To Oral Exams in Obstetrics and Gynecology - Questions & Answers-Springer International Publishing (2020) PDFDocument318 pagesGörker Sel - Practical Guide To Oral Exams in Obstetrics and Gynecology - Questions & Answers-Springer International Publishing (2020) PDFMohammed Khaleeq100% (2)