Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Jstore HRR PDF

Uploaded by

DEVI ARYANTARIOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Jstore HRR PDF

Uploaded by

DEVI ARYANTARICopyright:

Available Formats

Citing as a Site: Translation and circulation in Muslim South and Southeast Asia

Author(s): RONIT RICCI

Source: Modern Asian Studies , MARCH 2012, Vol. 46, No. 2, Sites of Asian Interaction

(MARCH 2012), pp. 331-353

Published by: Cambridge University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41478247

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

Cambridge University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access

to Modern Asian Studies

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Modern Asian Studies 46,2 (2012) pp. 331-353- © Cambridge University Press 2012

doi: 10.101 7/S0026749X 1 1 0009 1 6 First published online 1 2 March 2012

Citing as a Site: Translation and circulation

in Muslim South and Southeast Asia*

RONIT RICCI

School of Culture, History and Language , The Australian Natio

College of Asia-Pacific, Canberra, ACT 0200 Australi

Email: ronit.ricci@anu.edu.au

Abstract

Networks of travel and trade have often been viewed as central to understandin

interactions among Muslims across South and Southeast Asia. In this pape

I suggest that we consider language and literature as an additional type o

network, one that provided a powerful site of contact and exchange facilitated by

and drawing on, citation. I draw on textual sources written in Javanese, Malay

and Tamil between the sixteenth and early twentieth centuries to argue that

among Muslim communities in South and Southeast Asia, practices of reading,

learning, translating, adapting, and transmitting contributed to the shaping of

cosmopolitan sphere that was both closely connected with the broader, universa

Muslim community and rooted in local identities. I consider a series of 'citatio

sites' in an attempt to explore one among many modes of inter-Asian connection

highlighting how citations, simple or brief as they may often seem, are sites of

shared memories, history, and narrative traditions and, in the case of Islamic

literature, also sites of a common bond to a cosmopolitan and sanctified Arabic.

Introduction

Networks of travel and trade have often been viewed as pivotal to

understanding interactions among Muslims in various regions of South

and Southeast Asia. What if we thought of language and literature a

an additional type of network, one that crisscrossed these region

over centuries and provided a powerful site of contact and exchang

facilitated by, and drawing on, citation?

* I dedicate this paper to the memory of my much-missed teacher and mento

A. L. (Pete) Becker (1932-201 1).

331

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

332 RONIT RICCI

Among Muslim communities in

of reading, learning, translating

shape a cosmopolitan sphere that w

broader, universal Muslim commu

identities.1

The examples in the following pages are drawn from a range of

texts written in Javanese, Malay, and Tamil between the sixteenth

and early twentieth centuries, and preserved in manuscript and print

forms. I look at a series of what I envision as 'citation moments' or

'citation sites' in an attempt to explore one of the many modes of

inter-Asian connections. I wish to highlight how citations - simple or

brief, as they may often seem - are sites of shared memories, history,

narrative traditions, and in the case of Islamic literature, are also sites

of a common bond with a cosmopolitan and sanctified Arabic.

Studying translated circulating texts, written in local languages

infused with Arabic words, idioms, syntax, and literary forms, points

to contact and interactions not only among particular people but

also between and among languages such as the cosmopolitan Arabic

and vernaculars like Javanese or Tamil. Such interactions in turn

produced works in which pre-Islamic traditions were infused with

new meaning as well as compositions that inaugurated an era of new

literary expression.

Citation - from the Qur'an, religious treatises, histories of the

prophets, and in the form of Arabic expressions - created sites of

shared coherence and contact for Asian Muslims from different

localities. Retelling, translating, and citing common episodes and

beliefs set the stage for connecting through transmission, individu

contacts between scribes and translators, and a broad and sometime

elusive sense of belonging to a trans-local community. Citation ranged

from direct quotation to more general and less precise forms

adopting and adapting prior sources. The familiarity of shared stories,

ideas, and vocabulary contributed to the rise of similar educationa

institutions, life cycle rites, titles, names, and modes of expression an

creativity across great geographical and cultural spaces, and sustaine

multiple, shifting interactions among languages, individuals, and

communities.

1 For a discussion of the idea of an Arabic-centred cosmopolitanism in South and

Southeast Asia, see Ronit Ricci, Islam Translated: Literature , Conversion, and the Arabic

Cosmopolis of South and Southeast Asia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 201 1).

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 333

Citing sanctity: the shahäda

When we consider citation as a site of contact between Muslim

communities across Asia, there is perhaps no citation more pivo

than the shahäda, the Muslim profession of faith. By reciting its tw

brief sentences, the believer testifies to his or her faith that there

no God but Allah and Muhammad is His messenger. The shah

provides a point of contact between human and divine, and betw

Muslims of all regions, languages, and cultural backgrounds who utte

the same words attesting to their ultimate religious conviction.

As a mode of citation the shahäda takes several forms and is,

a way, emblematic of larger patterns of citation.2 Most broadly,

can be considered as a trope appearing in narratives depicting ear

Islamic history whose retelling introduced audiences to a distant

that came to be owned by all Muslims. It is cited almost universa

as a component of conversion rituals in depictions of individuals

communities embracing Islam; it is translated into local languag

making its translated citation a site of accessibility and familiar

and it is cited as an indication of a particular allegiance within diver

Islamic societies.

The shahäda is cited in historical chronicles that recount the

struggles, challenges, and successes of early Islam. It is often depicte

as a powerful means symbolizing and containing divine power. T

trend is apparent in the 1792 Javanese Serat Pandhita Raib? He

is found a rather fantastic retelling of the Prophet Muhammad

early struggle with the people of Kebar, the oasis (known as Khy

in Arabic) where a large Jewish population resided, one eventua

eliminated by Muhammad. The central figure, Pandhita Raib, is

Jewish leader and teacher who persuades kings already converted

Islam to forsake their new faith and battle the Prophet's armies.

day, when Pandhita Raib is about to go on a journey, a letter f

out of the sky. Upon opening it and realizing that it contains t

shahäda, Pandhita Raib is aghast. He commands that a great for

surrounded by moats, be built around the letter, barring entranc

all. However, when Pandhita leaves for his journey, his son Saib-

is drawn irresistibly to the fort and, through divine intervention

2 I refer here to textual citation, and do not address prayer and Qur'anic recitat

which could be analysed in a similar way.

3 Serat Pandhita Raib, Mangkunagaran Library, Surakarta, 1792, copied 1842.

MN 297.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

334 RONIT RICCI

able to enter it, finding the let

shahäda magically appearing in h

is sick with longing for the Proph

him and embraces Islam. The na

but the appearance of the shahä

ultimately to Saib-saib's convers

death. It is a sign of the futility o

and light, and a set of words so

most wise, strong, and cunning.

In an undated Malay variant of

Hikayat Raja Rähib , discussed by

gives birth to a son, who, after

a scrap of paper fallen from th

written. Knowing that their son i

his father tries to throw him into

angels and survives many adventu

Ali, and returning to convert his

It is noteworthy that in both c

form: although it is meant to be

use making it easy to commit t

special powers and is associated i

the non-believers and an irresistible draw. The written shahäda has

also long been associated with healing practices, as when a note with

its words is kept as an amulet or even ingested as a cure. In Java and

Sumatra, where most people could not read or write at the time these

manuscripts were inscribed, the power of the written word depicted

in these stories must have had particular resonance, magnifying the

shahäda's importance.

The shahäda is also referred to and cited in multiple narratives that

depict conversion to Islam and its recital constitutes a prerequisite

for anyone who wishes to become a Muslim. At times it is the only

element of a conversion ritual that is explicitly depicted, while at

others, additional elements like circumcision, a change of name, and

prayer are also included. Even when the latter is the case, the shahäda

remains the most prominent - and often only - citation that signifies

the transformation of the new believer and his entry into the Muslim

community. The shahäda doesn't have to be cited in full, and is often

only mentioned by the designation 'shahäda', íkalimah'> or ' kalimah

4 Ph. S. van Ronkel, 'Malay Tales About Conversion of Jews and Christians to

Muhammedanism', Acta Orientalia , 10, 1932, p. 59.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 335

kalih' and such mention is sufficient

their multiple resonances in the minds

In a textual example I employ throu

consistently appears. I am referri

languages as the Book of One Thousa

question-and-answer dialogue betwee

Ibnu Salam and the Prophet Muhamm

that ends with Ibnu Salam and all his

The conversion scene always includes

same is true in many other conversio

Southeast Asia.5

Next I wish to consider the question

without translation within Islamic tex

an undated Malay One Thousand Quest

Masalah , Ibnu Salam asks the Prophe

paradise on account of their dedicated

refers to a debate about whether Muslim

must follow certain prescriptions to at

a question is raised over the importa

Prophet replies [Malay, Arabic in bol

Hai Abdullah segala orangyang masuk syurga

menyebut la ilaha illallah Muhammad rasulu

dengan kebaktian. Jikalau Yahudi dan Nasrani

itu atau orang menyembah berhala sekali pun ji

O Abdullah, all those who enter paradis

deeds. Anyone who says la ilaha illallah

[entry to] paradise, without practicing the

a Christian says these two sentences, or

[by saying the above], he attains paradise.6

Beyond the central doctrinal issue ad

here the shahäda appears untranslate

that its two sentences are crucial ones,

them - including non-Muslims, even th

paradise. But what do they literally m

(discussed below) special care was tak

5 See, for example, Russel Jones, 'Ten Con

Nehemia Levtzion (ed.) Conversion to Islam (Ne

1979)>PP- !29-58-

Edwar Djamaris (ed.), Hikayat Seribu Masa

Pengembangan Bahasa Departemen Pendidik

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

336 RONIT RICCI

confession of faith that allows one to emb

to 'enter' - Islam, an opportunity of tra

this Arabic phrase is left as it is. Appe

power unrelated to semantic meaning, it o

commits an act of faith by uttering it. T

a word on Malay translation practices is

Some early translations from Arabic into

nature.7 As Islam spread, more texts w

more widely used as an Islamic language

tracts in Malay gradually gave way to tex

of Malay and Arabic. Malay became infuse

which appeared in all literary works, in

non-Muslim nature, like the Ramayana

with a focus on Islamic religious ideas o

Thousand Questions , tended to include

quotes from the Qur'an, hadith, and other

a dual-language version as did interlinea

The point of transition from interline

not clear-cut and interlinear translation

Perhaps because many readers of the time

translations while studying and to the A

towns - or at least to its religious termin

and Qur'anic recitations - the One Thousan

to assume a better knowledge of Arabic

than the Javanese and Tamil tellings do

and expressions of great importance, lik

God's creative powers, conventionalized

God and the Prophet, and selected qu

thought to be familiar enough not to requ

explanation is that understanding - wh

not matter much, or at least was not cons

of knowledge. As is often the case presen

communities, a reading knowledge of A

is quite prevalent, and certain words,

on a regular basis. Some of this vocabu

7 The practice of interlinear translation of th

translations from Arabic to Persian, which, acc

permitted only if the Persian was accompanied by

for-word translation (A. tarjamah musawiyah , equ

Muslims into other languages tended to follow t

Qur'an Translatable?', The Muslim World , 52, 196

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 337

reciting the Qur'an is entailed - would

many readers and speakers if they wer

meaning of single words or complete s

are important functions to these uses, wh

status of Arabic and to its sanctity, and w

knowledge in a conventional, scholastic,

If we consider this possibility, the app

shahäda in the midst of a paragraph pro

at all who will recite its words no longer s

Islamic mantras in Sanskrit, valued for

than their lexical meaning, in a simila

gained much esteem. Such phrases were

and Javanese, as lapal or rapal. They cons

prayers or spells that exerted power by v

even while their meaning was foreign, es

Arabic, whether understood or not, was

and prestige because of its status as the

was revealed to Muhammad. When left un

lapal , quotes from scripture, and the had

well, pointing to the authority residing i

listeners were often unable to judge its

the accuracy of a quote. In this way eve

Qur'anic citation, for example - was ac

the specific example of the shahäda, a com

and meaning probably played a role, as

and Muhammad's mission was indeed a

the many other lapal, scattered untran

Arabic bestowed on the text the autho

such words are often preceded by: 'As G

(M. seperti firman Allah Ta'ala di dalam Qu

quote.

Returning to the shahäda, it can also appear in Arabic along with

a translation. In the Javanese One Thousand Questions (Serat Samud or

8 The question of 'corrupt' or false citation is a loaded one in general, and is

also specifically relevant to the One Thousand Questions. There are at least two types of

'corruption accusations': those (mostly by Muslim scholars) discussing the relationship

of the Prophet's words as presented in the text to his 'real' words, and those (mostly

by Western scholars) discussing spelling, grammatical, and syntactical mistakes. See,

respectively, Ismail Hamid, The Malay Islamic Hikayat (Bangi: Universiti Kebangsaan

Malaysia, 1983), and Guillaume Frederic Pijper ,Het boek der duizend vragen (Leiden: E.

J. Brill, 1924).

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

338 RONIT RICCI

Suluk Samud) tradition, it is almost inv

it appears in Javanese only, without the A

In an 1884 Serat Samud from Yogyakar

reply about Islam as the true religion,

Salam asks what the word 'Islam', in fact,

meaning of Islam (or becoming, being M

shahäda). Then the Prophet explains wh

boldface):9

Ashadu ala prituwin

ilaha ilalah lawan

ashadu ana lan maneh

Mukamadarrasul Allah

sun nakseni tan ana

pangéran lyaning Hyang Agung

Mukamad utusan ing Hyang

The profession of faith - the two most sacred sentences attesting to

the oneness of God and to Muhammad being His messenger - appears

in Arabic but is interspersed with Javanese (in boldface in translation):

I bear witness [that there is] no and also

God but Allah and

I bear witness in addition

Muhammad is God's messenger.

This is the Arabic quote within which - even before reaching the

translated portion - the author inserts some Javanese words to parse

the two sentences that comprise the sadat , so that it makes more sense

to the listener and is more readily memorized. Again, due to its utmost

importance, special care is taken that it will be clearly understood -

not just its general meaning, but also the specifics of each segment.

The translation into Javanese follows, using the same divisions of

meaning:

I bear witness there is no

God but Hyang Agung

Muhammad [is] Hyang's messenger.

The translation is accurate, with an interesting variation: the word

Allah is not used for God in the Javanese rendering, but rather it

employs two Javanese terms: Pangéran , means God, Lord, and is also a

9 Serat Samud , Pura Pakualaman Library, Yogyakarta, 1884. MS. PP St. 80. 1.34.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 339

royal title, and Hyang or Hyang Agung, a

or Hindu deities. We find here, to borr

a translation that combines the iconic m

content elements of the original) with an

text is embedded in a locale, a context, re

much sense without it).10

Looking to the example of the confes

for Javanese and Malay, in the 1572 T

Questions (Ayira Macalä ), we find it ap

its complete form in Arabic without tran

kalimä without further detail.11 For ex

rows, are described as endlessly recitin

mcülullä. Ibnu Salam, when embracing

the kalimä along with his 700 followers

Tamil text's general emphasis on local con

its message, there is no instance of the sh

Since the One Thousand Questions is

writing in Tamil, it is likely to have in

periods. Discussing the later, undated, Tam

Mälai , David Shulman notes the impre

Persian and Urdu words into the Tamil te

than the reverse trend, the use of non

to convey Muslim concepts.13 Tamil lit

Thousand Questions with Umäruppulavar

of the Prophet), written a century lat

century. Many of the miracles only h

Questions were depicted at length in th

entire chapters, and much of the sam

in the One Thousand Questions was inc

the later text. Umäru, author of thi

Muslim literary works, is known as a d

10 A. K. Ramanujan, 'Three Hundred Rama

Thoughts on Translation', in Paula Richman (ed

of a Narrative Tradition in South Asian (Berkeley:

P- 45-

Vannapparimalappulavar, Ayira Macala, 1572, (ed.) Cayitu 'Hassan

Muhammatu. (Madras: M.Itris Maraikkayar/Millat Press, 1984).

Vannapparimalappulavar, Ayira Macalä , Verse 254 for the angels; 1052 for the

conversion.

David Shulman, 'Muslim Popular Literature in Tamil: The Tamïmancàri Mälai'

in Y. Friedmann (ed.), Islam in Asia (Jerusalem: Magnes, 1984), Vol. 1, pp. 174-207;

p. 207, note 1 14.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

340 RONIT RICCI

Thousand Questions' author Vann

shows how early citations - of A

events - continued to circulate a

their meaning reinforced and re

I have explored the way in wh

a potent message, able to overcom

powers and to draw non-believers t

early spread; its consistent appear

as the single most important

partial, and non-translation in lo

the shahäda could also point to a

Muslim communities. For exam

Thousand Questions in Persian w

'Ali is God's wali', its inclusion

these instances, as well as in the f

prayer and Qur'anic reading, it b

identification for Muslims in Asia.

A cosmopolitan script - contact and interaction through

shared orthography

Yet another site of citation, in a very literal sense, is found in the

adoption of the Arabic script by Muslim communities in South and

Southeast Asia to write their own languages, a strategy that was

of paramount importance to the emergence of a shared Muslim

affiliation in these regions. It was a critical aspect of contact with

Arabic, one that transformed local languages and defined them

anew, as changing a script has far-reaching cultural implications. As

A. L. Becker observed in the context of transliterating Burmese into

Latin script, 'writing systems. . . are among the deepest metaphors in

a language. . . they resonate richly throughout a culture, and so for us

to substitute one technology of writing for another is not a neutral act,

a mere notational variation. It means to re-imagine language itself.'16

Writing in the cosmopolitan Arabic script was an act of reimagining

14 Vannapparimalappulavar, Ayira Macalä, Introduction, p. 3.

5 Pijper, Het boek , p. 60.

A. L Becker, Beyond Translation (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1995),

p. 234.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 341

and reformulating the languages of

speaking Muslims.

The employment of Arabic script

significantly enhanced other aspects o

into these languages. Known as jawi

Javanese, and arwi for Tamil, using Ara

and more accurate rendering of imp

sustained - as far as possible, consider

systems - a correct pronunciation of Ar

chance of misunderstanding and err

South and Southeast Asian languages

the most sacred of languages, placing th

Islamic languages and making their te

into revered objects.

In some instances, like Persian, the Ar

form of writing. Malay was written in

overshadowed by Arabic writing until t

the sixteenth century. In many othe

and Javanese are examples - an olde

alongside the new Arabic script. Wheth

exclusively or not, the shift from a prio

Scripts are embedded in particular c

often associated with creation narrat

educational and social practices. Many of

with changes in script. With the ado

communities in South and Southeast

were lost or marginalized, while a cer

was achieved. As the cross-regional us

a shared religious vocabulary, so the

cultural and geographical distance con

an orthographically unified religious co

The adoption of the Arabic script, w

speakers of Tamil, Javanese, and Mala

of their literary cultures, including cit

The script adopted in all three cases w

existing Arabic letters with diacritic

the particular sounds of each langua

differed somewhat from one another

or identical Arabic citations to appea

Malay works. They also facilitated th

volumes written in Arabic script. An un

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

342 RONIT RICCI

mystical poetry and praise for

1 800 and used as a textbook for

Several copies, resembling one

written in Indonesia: a copy from

Persian; a copy from Aceh con

single page in Malay; a third c

poems in Arabic and Persian. Y

in Arabic, some in Persian and

unidentified (possibly Indian) l

Among the three languages m

influenced by Arabic was M

studied an additional - and s

influence on this language, dis

Influence of Arabic Syntax on

argued, to examine how Arabi

order to better understand the i

languages on Malay, we must als

syntactical structures, which we

How texts were translated f

evidence for what Van Ronk

method, through which variou

narrative in form, employed

convey Arabic prepositions, g

Malay. Although translations e

partial, Malay text with some Ar

Arabic constructions was consist

that deeply influenced Malay gr

For example, Van Ronkel foun

consistently translated as Malay

dengan nama (rather than the gr

Malays were borrowing the Arab

Malay term setengah orang (liter

17 Petrus Voorhoeve (ed.) Handlist of Ara

of Leiden and Other Collections in the Ne

PP- 456-58.

I have used the Indonesian translation of this work, originally published in

Dutch in 1899. Ph. S. van Ronkel, 'Over de Invloed der Arabische Syntaxis op de

Maleische', Tijdschrift voor Indische Taal- Land- en Volkenkunde , 41, 1899, pp. 498-528.

A. Ikram (trans.), Mengenai Pengaruh Tatakalimat Arab Terhadap Tatakalimat Melayu.

Vol. 57 (Jakarta: Bhratara, 1977).

y Van Ronkel, 'Over de Invloed', pp. 15-16.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 343

meaning 'many people') derives from Arab

there is an intrinsic similarity in the way

a preposition or other grammatical mar

the Arabic form was foreign to Malay an

to imitate the Arabic as precisely as po

manner Arabic citation was internalize

gradually transforming it.

Another site for assessing this proc

accommodation, and quite concretely at

Arabic script and transliterated ( rumi

Malay One Thousand Questions in transli

italicized by the editor and thus 'jumpi

print equivalent of Arabic words - or,

expressions - appearing in ink of a di

or grey) among Malay words written i

many manuscripts. These techniques allo

by scribe, reader, and reciter - of the

of certain words and whether the scribe considered them to be

Arabic or Malay, since the two languages were written in script

that were almost identical. Both methods - in manuscript and prin

allow an examination of the way in which many words of Arab

origin appear side by side with the highlighted quotes, unobserve

taken as an integral part of the Malay language by the time t

One Thousand Questions manuscript was inscribed. A similar analy

can be carried out for Javanese manuscripts written in Arab

script.

Beyond the realm of manuscripts and books, Arabic script was to

be found above all in the Indonesian Archipelago on tombstones, with

the earliest instance in Java dating from the fourteenth century.21

In the Tamil region, Arabic epitaphs in Kayalpattinam, dating from

the fifteenth century, record names and Hijri death dates. Some

include sections of religious text, genealogies, and occupations like qädl

(judge), amïr (military title), and täjir (learned merchant), employing

the Arabic titles of the kind routinely adopted by rulers, members

of the nobility, and literary figures in both southern India and the

20 These examples appear in Van Ronkel, 'Over de Invloed', pp. 25 and 37,

respectively.

21 M. C. Ricklefs, Mystic Synthesis in Java. A History of Islamization from the Fourteenth

to the Early Nineteenth Centuries (Norwalk: EastBridge, 2006), p. 12.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

344 RONIT RICCI

Archipelago.22 These citation

sphere, point very concretely

linked Muslims across divides o

Paratexts as citation sites

In his monumental book, Paratexts : Thresholds of Interpretation, literar

scholar and critic Gerard Gennette explored those bits of text such

as the author's name, the title, preface, and illustrations - to name

few - that surround and extend the text, present it to its readers, and

act as a threshold for those who consider whether to enter it or ste

back.23 For example, a provocative title may cause a potential reade

to pick up a book by an obscure author, while a translator's note may

shape readers' interpretation of a novel by introducing them to th

author's life history and her circumstances of writing.

Certain oft-used citations that accompany Islamic texts can be read

as paratexts. The bismillah al-rahman al-rahlm ('in the name of God, th

compassionate, the merciful') is prominent among them. The bismillah

opens every surah of the Qur'an (except the ninth),24 and tradition

ascribes to the Prophet Muhammad the saying that any work not

begun with it will remain incomplete or ephemeral.25 Well-know

traditions in Arabic tell of letters sent out by Muhammad to kings and

leaders of his era, including Heraclius, the Byzantine emperor, th

governor of Bahrain, and the king of Persia. The letters began wit

the bismillah greeting, mentioned that the Prophet was the sender, an

invited the leaders to accept Islam, promising rewards if they did and

hardship if they refused.26 Small wonder then, that with such a history

and aura, the phrase appears as a matter of course as the opening line

of many Islamic texts in South and Southeast Asia, and especially i

those composed in a local language but written in the Arabic script

22 On the Kayalpattinam tombstones, see M. Shokoohy, Muslim Architecture of South

India. The Sultanate of Ma'bar and the Traditions of Maritime Settlers on the Malabar an

Coromandel Coasts (Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Goa) (London: Routledge, 2003), pp. 275-90

Gerard Genette, Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation , trans. Jane E. Lewin

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1997).

24 A surah is a division of the Qur'an, sometimes referred to as 'chapter.' The Qur'a

contains 1 14 surahs of varying lengths.

25 Tayka Shu'ayb 'Ahm, Arabic, Arwi and Persian in Sarandib and Tamil Nadu (Madras:

Imämul 'Arüs Trust, 1993), p. 671.

¿ Muhammad ibn Abd Allah al-Khatib Tibrizi, Mishkat Al-Masabih, trans. James D

Robson (Lahore: Sh. Muhammad Ashraf, 1963), pp. 832-33 (4 vols).

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 345

In such instances it not only provides a

content and religious significance but a

in a seamless manner. The bismillah ca

Arabic and translation, or in translation

maintains its prominent initial position in

to be read or heard by its audience.

The 1884 Serat Samud provides an exa

(in a somewhat Javanized form) is hig

translation. In this case it appears as the o

a text - a letter addressed by the Prophet

his letters to other leaders and communit

Wit ing surat bismillahi rahmani rakimi ika.

The letter opens with bismillahi rahmani rakim

This line is directly followed by a

explanation, of the Arabic phrase:

Tegesé miwiti ingong

anebut naming suksma

ingkang murahing dunya

nora nana kéwan luput

tembé asih ning akérat

This means I begin

by speaking the name of God

who is merciful in this world

towards all living creatures

[and] compassionate in the next world.

Here the Javanese author expands and expounds on the literal

meaning of this important and familiar Arabic phrase. In the

translation not only is God described as merciful and compassionate,

as in the Arabic original, but these attributes are infused with context

and life, stressing that all creatures are beneficiaries of His mercy and

inserting, quite subtly but forcefully, the notion that human existence

does not end with death but rather continues in another world where

God's compassion reigns. In the context of Muhammad sending his

letter within the narrative framework, this depiction is important as

it stresses for the Jews the omnipotence of Muhammad's God; in the

larger context of a Javanese audience listening to the Serat Samud ,

the bismillah is recited in Arabic, translated, and given meaning that

27 Serat Samud , Pura Pakualaman Library, Yogyakarta, 1884. MS. St. 80.1.9.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

346 RONIT RICCI

is relevant, on several levels, to all pre

a common citation echoing the Qur'an

guide to Muslim letter-writing codes, a re

a brief lesson in Arabic's sacred terminolo

In the Tamil rendering of the same na

the letter to the Jews opens similar

archangel Jipurayïl (Gabriel) arrives as

his companions and tells him to write

leader Ipunu Caläm. Muhammad immed

summoned so that the letter, dictated b

and delivered.28

The letter is then dictated by the Prophe

its content from the archangel:

First write: bismillähi rahumänil rahïm

the words of God's messenger are written

I am Muhammad

I [teach] God's exalted way

In this world, to all.

All will be blessed

Those who take the right path - that of the mustakïm , steadfast in it

Will gain prophet and sorkkam

Listen to my words and you will succeed.29

At the other end of such texts is found yet another, even briefer,

paratext: many Malay hikayat (from A. hikäya ) - a broad genre that

encompasses romances, adventures, theology, and history - end with

the statement tamat al-hikayat' thus ends the hikayat , or simply 'the end'.

Other typical endings for Malay writing are tamat al-qaläm and tamat

al-kitäb. Tamat ends Javanese works as well. Although these phrases

are not endowed with any of the sanctity of the bismillah they are

nevertheless Arabic phrases, and as such carry an echo of a distant,

foreign literary culture - its genres, idioms, and sounds - that has

come to be experienced as familiar and close to Muslim audiences

in Asia. The tamat phrase is sometimes followed by brief mention of

a manuscript's author or the name of the scribe who copied it, and

the time and place of writing. Even when these identifying details do

not appear, there is often mention of the blessings to be incurred on

those engaging with the text, through writing, copying, listening or

storing it. The following three examples are intended to point to the

28 Vannapparimalappulavar, Ayira Macalä , p. 14.

¿ Vannapparimajappulavar, Ayira Macalä , p. 17.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 347

prevalence of this brief paratext, a cit

cultures and sites, connecting them throu

always in a text's significant closing lines

In the late seventeenth/early eighteenth

manuscript likely written along the north

Tamat carita nira Samud tinulis

yèku tandha nira

yen nabi utusan luwih

saking sakèhing dumadya

Thus ends the story written about Samud

it is your sign (it signifies)

that the Prophet (and) Messenger is best

Among all living creatures.30

In the late nineteenth century Hikayat Tuan Gusti , a Malay

manuscript from Sri Lanka:

Tamat Hikayat Tuan Gusti tengari bulan Sa'aban 21 bulan Inggris 22 Januari hijrah

189 J menulis Subidar Mursit pension Selon raifil rajimit jua adapun aku pesan pada

sekalian tuanyang suka membaca hikayat ini jangan saka qalbunya supaya dirahmatkan

Allah subhanahu wa-ta'ala dari dunya sampai keakirat

Thus ends Hikayat Tuan Gusti at midday on the 21st of Sa'aban the 22nd of

January 1897. It was written by Subidar Mursit, a retiree of the Ceylon Rifle

Regiment. I ask all those who found pleasure in reading this hikayat : do not

(let it fade) from your hearts so that you will be granted mercy by Almighty

God - praise be upon Him - in this world and the next.31

In Hikayat Patani, copied in Singapore in 1839 by Abdullah bin Abdul

Kadir on behalf of the missionary Alfred North, and likely to have

been based on a manuscript from Kelantan in Northeast peninsular

Malaysia, near the border with Thailand:32

Tamat alkalam. Bahawa tamatlah kitab Undang-Undang Patani ini disalin alam

negeri Singapura kepada sembilan hari bulan Sya'aban tahun I2^^sanat, iaitu kepada

enam belas hari bulan Oktober tahun Masihi i8^çsanat. Tamat adanya.

30 Samud , Leiden University, Oriental manuscripts collection, late seventeenth

century [?]. MS. LOr 4001.

Hussainmiya Collection, National Archives of Sri Lanka, Colombo, reel 182.

32 Hikayat Patani, Malay Concordance Project. See: <http://mcp.anu. edu.au/N/

Pat_bib.html>, [accessed 17 December 2011].

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

348 RONIT RICCI

The End. Thus ends the Patani Book of Laws

of Sya'aban AH 1255, namely the sixteenth

As Genette emphasized, the paratext i

between inside and out, an edge or fr

controls one's whole reading of it. We

and tamat phrases in light of Genette'

always the conveyor of a commentary th

legitimated by the author, constitutes

text, a zone not only of transition but al

place of a pragmatics and a strategy, of a

influence that - whether well or poorl

at the service of a better reception of

reading of it.'34 The paratexts in a work'

or otherwise) are of special importance

reader or listener, setting the tone at

particular message or mood in the clo

explored, texts of diverse linguistic and g

framed by, or contained within, share

These reminded audiences of their broad affiliation with a trans-

regional community.

Defying translation: sites of untranslated citation

Despite the somewhat different approaches to incorporating Arabic

and employing translation within the texts, in all three languages

mentioned, certain words defied translation. I have already noted

the appearance of the untranslated shahäda but there are many

additional examples. There is room for speculation on why certain

Arabic words were adapted verbatim into these languages, whil

others were rendered in the local language. It is likely that some

words expressed concepts novel to the society into which they wer

introduced, so word and idea were accepted together. A certain power

associated with the incomprehensible can also explain why some words

were left untranslated. This includes both the idea that words can

33 The repetitive use of tamat in this citation is somewhat unusual. Its final

appearance, tamat adanya , may emphasize that this is the end of the entire text rather

than an end of a section. I am grateful to the late Ian Proudfoot for discussing the

uses of tamat with me.

34 Genette, Paratexts, p. 2.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 349

effect change and alter reality regardle

and the notion that foreign concepts s

the retention of the foreign terminology.

appeared as such, untranslated in the M

of One Thousand Questions , provides an e

The munäfiqün - mentioned over thre

were residents of Medina in the seven

converted to Islam but did not adhere

religion. Officially Muslim, but in fac

the Prophet, they constituted a threa

translated into English as 'hypocrites',

stronger and has a wider semantic rang

are described as liars, obstructers, igno

and deviant. They were clearly dissent

emerging Muslim community, refusing t

and deserving of hellfire.

In contrast to the mostly general terms

referred to in the Qur'an, later Islami

to ascribe the term to specific perso

word in a sense that came closer to 'hyp

approximation of the term may be 'dis

both in private and public, and carryin

schism.35

In the One Thousand Questions tellings discussed, this group, referred

to as munapik , appears as a category of people who are surely

destined for hell. In all three languages a question arises as to their

nature and the same reply is offered by the Prophet: a hypocrite is

outwardly Muslim but inwardly an infidel (< kapir , from A. käfir , another

untranslated term). Clearly, even many centuries after the historical

munäfiqün betrayed the Prophet, this group - or anyone resembling its

members - still connoted deceit and hypocrisy, and was portrayed in

the most negative light. The torments they will suffer were vividly

depicted in the One Thousand Questions tellings. But why was a Tamil,

Malay or Javanese word not used to name this group? It may be

that certain terms remain untranslated because they are so deeply

embedded in a particular historical and cultural event that their

35 A. Brockett, 'al-Munäfikün', in P. Bearman, Th. Bianquis, C. E. Bosworth, E.

van Donzel and W. P. Heinrichs (eds) Encyclopaedia of Islam, 2nd edition (Leiden: Brill,

2010) Vol. VII, p. 561.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

350 RONIT RICCI

mention arouses an entire set

no longer be accessible in trans

This phenomenon of the untran

is related in turn to the notion

the ways in which thoughts, wr

upon, texts that are shared by m

Muslims are familiar with imp

which the citations on the mun

Prophet's conflicts with the mun

not be evoked in the same manner in the minds of listeners familiar

with the Qur'an if a (more neutral) Javanese word were substituted for

the Arabic. The importance of conveying the full weight of the original

term was in part due to the fact that the text dealt with conversion

and was likely to have been discussed with the recently converted, for

whom it was crucial to understand that their acceptance of Islam must

not be in appearance only, but total.

The second explanation is more culturally specific: the notion of

religious hypocrisy or dissent, of believing inwardly in one thing but

posing externally as another, was foreign to the three local cultures

before the arrival of Islamic notions of faith. Earlier belief systems

in the Archipelago included indigenous systems, in addition to Hindu

and Buddhist traditions that had acquired a local character. Similarly,

that which is today referred to as Hinduism in the Tamil region, as well

as worship of local warrior gods, goddesses, and saints, prevailed at the

time the text was composed. The strict Judeo-Islamic notion of a single,

clearly defined belief that must be followed exclusively and must not

conflict with appearances or words was not a component of these

earlier and concurrent traditions and, therefore, a word conveying the

charged significance of munapik was unlikely to have existed.

Leaving words like munäfiq , käfir (infidel), nabi (prophet), qiyäma

(Judgment Day), and others untranslated (although their spelling and

pronunciation were somewhat modified) contributed to the creation

of a trans-regional, standardized Islamic vocabulary across South and

Southeast Asian Muslim societies. Such standardization, along with

the common use of titles, epithets, and stories, in turn helped shape

a religion-based community that was culturally and linguistically

diverse. It allowed Muslims from places distant from the Muslim

'heartland', like Java, to take part in and belong to the life of a global

36 Becker, Beyond Translation , pp. 285-93.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 351

community that was defined, in part

language.

In light of the tendency to leave certain words untranslated, it is

tempting to suggest a typology of words that continued to be used

in Arabic rather than translated into the local languages. Following

the ' munapik paradigm', there would be a host of terms that could

be expected to remain untranslated within the texts. The situation,

however, is far from consistent: many words that fit into the munapik

category of novelty, forcefulness, and linkage to prior texts, did in fact

appear in translation. Not only were they translated but, as in the case

of using Tamil marai (veda) for the Qur'an or Javanese hyang for Allah,

they were expressed through the use of religious concepts belonging

to a different belief system.

A clear example is found in the case of the terminology for paradise

and hell, both key concepts in Muslim thought which are discussed

and portrayed in many texts. Often teachings and warnings regarding

life in this world in fact focus on the prospect of residing in either

hell or paradise in the future. In the case of such central concepts,

an adoption of Arabic terminology that would powerfully enhance the

depictions impressed upon the faithful might be expected. However,

in the Tamil, Malay, and Javanese One Thousand Questions , the older,

Sanskritic terms swarga (paradise) and naraka (hell) are employed

exclusively and consistently.

Notions of swarga and naraka in non-Islamic texts differ markedly

from their use within a Muslim context. Swarga was the world of the

gods and demi-gods who enjoyed lives of pleasures before recurring

rebirths; naraka , often depicted as a netherworld of suffering, was

teeming with demons and other creatures and was, yet again, a

temporary stop in the cycle of reincarnation. In contrast, in Muslim

teachings, these two realms came to signify the two mutually

exclusive, eternal fates for the good and the evil. This prospect meant

that the terms swarga and naraka assumed new, dramatically loaded

meanings with the transition to Islam. Keeping old terminology

within the context of a new system - religious or otherwise - carries

the risk of misunderstanding, confusion, and conflation. Creating

a neologism or bringing in foreign, and sacred, vocabulary - as was

often done with Arabic - allows for a distancing from old ideas and

a more detached introduction of the new. The break with the past is

not necessarily smooth but is more radical.

The cases of Javanese, Tamil, and Malay are interesting precisely

because of an inconsistency, a combination of terminology and

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

352 RONIT RICCI

metaphors that does not fully

every case where an Arabic w

cited untranslated, a counter-e

with earlier (or concurrent) be

possible confusion and blurrin

the Javanese Babad Jaka Tingk

names of categories of learned

were exchanged with the new

roles and attitudes was reflecte

much of the literature, termin

effortlessly without authorial co

and naraka an older Sanskrit cita

in the Indonesian-Malay world

overlap with, or at times be re

continued to exert its influence

affiliations had shifted.

Concluding thoughts

Various forms of citation - whether single Arabic words, direct quotes

from the Qur'an or paraphrases of well-known histories of the

prophets, episodes from Muhammad's life or commonly used hadith -

appeared widely within Islamic literary sources in Tamil, Malay, and

Javanese. I have examined such practices of citation as creating and

sustaining sites of connection and interaction across Muslim societies

in Asia and beyond.

The shahäda (in Arabic and in translation), for example, as well as

famous sayings of the Prophet, can be viewed as loci of authority that

exerted power and bound readers and listeners from all walks of life

to a shared core of ideas, stories, and beliefs. These - and additional

citations - formed the basis for common educational models, authority

structures, a shared imagination, and historical consciousness.

Citations in the textual sources discussed were not always 'correct'.38

Rather, they were often truncated, had words missing or sounds

37 Nancy K. Florida, Writing the Past , Inscribing the Future: History as Prophecy in Colonial

Java (Durham: Duke University Press, 1995), p. 155.

Pijper discussed the use of Qur'anic quotes in the Malay One Thousand Questions

and, noting their frequent 'corruption,' assumed they were cited from memory. The

result was a form of Arabic that drew more heavily on sound - the way words were

heard by a Malay ear - than on accurate spelling, as may be expected in the context

of a predominantly oral literary culture. Also, frequent Qur'anic recitations in which

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

CITING AS A SITE 353

misrepresented in local scripts or pr

in such forms represented the many

place - that had transpired prior to th

in writing in towns along the Corom

In the case of the Book of One Thousa

example, I proposed that much significa

sounded familiar and authoritative, and

important story set in the Prophet's tim

over an earlier religion.

These connections occurred at sev

levels: through a familiarity with the s

a common use of the Arabic script fo

shared repository of names and title

tombstones and mosques, and in live

contact between individuals, commu

ideas. Translators, scribes, patrons,

listeners all participated in various w

bringing about profound linguistic an

articulate the richness and variety that

is to consider, as I have suggested, the

with citation-sites along their paths.

Arabic was heard but not necessarily seen by m

it in writing had to be made via aural memory.

This content downloaded from

202.43.95.117 on Mon, 26 Oct 2020 07:00:35 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Review Macdonald PDF 1Document3 pagesReview Macdonald PDF 1Ember lordofFireNo ratings yet

- ARTS017 Tutorials - Notes - On History of ArabiaDocument2 pagesARTS017 Tutorials - Notes - On History of ArabiaAfshan RahmanNo ratings yet

- Wolf - The Social Organization of Mecca and The Origins of IslamDocument29 pagesWolf - The Social Organization of Mecca and The Origins of IslamRaas4555No ratings yet

- Sufi Cosmopolitanism in The Seventeenth-Century Indian Ocean, PeacockDocument28 pagesSufi Cosmopolitanism in The Seventeenth-Century Indian Ocean, PeacockaydogankNo ratings yet

- Barbarians in Arab EyesDocument17 pagesBarbarians in Arab EyesMaria MarinovaNo ratings yet

- What Is Islam?: The Importance of Being IslamicFrom EverandWhat Is Islam?: The Importance of Being IslamicRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Cambridge University Press, Harvard Divinity School The Harvard Theological ReviewDocument42 pagesCambridge University Press, Harvard Divinity School The Harvard Theological ReviewyumingruiNo ratings yet

- Hamza Abbas Islamic SectionalDocument6 pagesHamza Abbas Islamic SectionalWasif KhanNo ratings yet

- PolycentricDocument21 pagesPolycentricJannah Joy LlanaNo ratings yet

- 859-Article Text-1438-1-10-20210411Document12 pages859-Article Text-1438-1-10-20210411ਕੀਰਤਸਿੰਘNo ratings yet

- Educational System in The Time of ProphetDocument24 pagesEducational System in The Time of ProphetAMEEN AKBAR100% (3)

- Historicizing The Study of Sunni Islam in The Ottoman Empire, C. 1450-c. 1750 - Tijana KrstićDocument29 pagesHistoricizing The Study of Sunni Islam in The Ottoman Empire, C. 1450-c. 1750 - Tijana KrstićZehra ŠkrijeljNo ratings yet

- Reflections On 'Abd Al-Ra'uf of Singkel (1615-1693)Document26 pagesReflections On 'Abd Al-Ra'uf of Singkel (1615-1693)Muhammad AfiqNo ratings yet

- The Book of AbrahaM and The Islamic Qiṣaṣ Al-Anbiyā (Tales of The Prophets) Extant LiteratureDocument21 pagesThe Book of AbrahaM and The Islamic Qiṣaṣ Al-Anbiyā (Tales of The Prophets) Extant LiteratureMerveNo ratings yet

- Salikuddin Dissertation 2018Document262 pagesSalikuddin Dissertation 2018ظفر حسین چوٹیال اعوان100% (1)

- A Glimpse of Tolerance in Islam Within The Context of Al-Dhimmah People (Egypt and Baghdad Model)Document13 pagesA Glimpse of Tolerance in Islam Within The Context of Al-Dhimmah People (Egypt and Baghdad Model)JOURNAL OF ISLAMIC THOUGHT AND CIVILIZATIONNo ratings yet

- 08kahteran Rumi's Philosophy of Love PDFDocument12 pages08kahteran Rumi's Philosophy of Love PDFSejfullah MelkićNo ratings yet

- Richardson RecollectingReconfiguringAfflicted 2012Document25 pagesRichardson RecollectingReconfiguringAfflicted 2012Mehreen bilalNo ratings yet

- Singing with the Mountains: The Language of God in the Afghan HighlandsFrom EverandSinging with the Mountains: The Language of God in the Afghan HighlandsNo ratings yet

- Knysh On Wahdat PolemicsDocument10 pagesKnysh On Wahdat PolemicsashfaqamarNo ratings yet

- The Power of The Heart That Blazes in The WorldDocument28 pagesThe Power of The Heart That Blazes in The WorldAhmad AhmadNo ratings yet

- Tran Skrip TDocument28 pagesTran Skrip TFarhanah Shakirah FauziNo ratings yet

- South Asian Quran Commentaries and Trans PDFDocument25 pagesSouth Asian Quran Commentaries and Trans PDFفخر الحسنNo ratings yet

- Tessellations in Islamic CalligraphyDocument6 pagesTessellations in Islamic CalligraphyPriyanka MokkapatiNo ratings yet

- Edinburgh University Press Islamisation: This Content Downloaded From 148.252.129.242 On Mon, 08 Apr 2019 21:58:05 UTCDocument18 pagesEdinburgh University Press Islamisation: This Content Downloaded From 148.252.129.242 On Mon, 08 Apr 2019 21:58:05 UTCZara AlexanderNo ratings yet

- Adnan J Almaney - Cultural Traits of The ArabsDocument10 pagesAdnan J Almaney - Cultural Traits of The ArabsHada fadillahNo ratings yet

- 5654 25079 6 PBDocument14 pages5654 25079 6 PBOktri PamungkasNo ratings yet

- Puṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 2From EverandPuṣpikā: Tracing Ancient India Through Texts and Traditions: Contributions to Current Research in Indology, Volume 2No ratings yet

- Maarif July 2017-07Document23 pagesMaarif July 2017-07Hassan BaigNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 5.169.173.0 On Sun, 31 Oct 2021 14:11:26 UTCDocument24 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 5.169.173.0 On Sun, 31 Oct 2021 14:11:26 UTCAiman RashidNo ratings yet

- Palaces, Pavilions and Pleasure-Gardens PDFDocument27 pagesPalaces, Pavilions and Pleasure-Gardens PDFHasina AhmadiNo ratings yet

- On The Genesis of The Aqîqa-Majâz DichotomyDocument31 pagesOn The Genesis of The Aqîqa-Majâz DichotomySo BouNo ratings yet

- Communities of the Qur'an: Dialogue, Debate and Diversity in the 21st CenturyFrom EverandCommunities of the Qur'an: Dialogue, Debate and Diversity in the 21st CenturyRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- AJISS FederspielDocument4 pagesAJISS Federspielseekay20006756No ratings yet

- Seyyed Hossein Nasr - Rūmī and The Sufi TraditionDocument12 pagesSeyyed Hossein Nasr - Rūmī and The Sufi TraditionDhani Wahyu MaulanaNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 43.252.248.86 On Wed, 02 Mar 2022 15:08:45 UTCDocument15 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 43.252.248.86 On Wed, 02 Mar 2022 15:08:45 UTCroshniNo ratings yet

- From Sasanian Mandaeans To Ābians of The MarshesDocument163 pagesFrom Sasanian Mandaeans To Ābians of The MarshesFiqih NaqihNo ratings yet

- The Path of God's Bondsmen from Origin to Return [translated]From EverandThe Path of God's Bondsmen from Origin to Return [translated]Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (2)

- EDC 500 Religion PaperDocument8 pagesEDC 500 Religion Paperwellmac1No ratings yet

- Muslim Pilgrimage in the Modern WorldFrom EverandMuslim Pilgrimage in the Modern WorldBabak RahimiNo ratings yet

- THE EMINENCE OF POETIC ARABIC LANGUAGE: LAMIYYAT AL ARAB OF ASH-SHANFARA EXAMPLE - سمو اللغة العربية الشعرية: لامية العرب للشنفرى أنموذجاDocument12 pagesTHE EMINENCE OF POETIC ARABIC LANGUAGE: LAMIYYAT AL ARAB OF ASH-SHANFARA EXAMPLE - سمو اللغة العربية الشعرية: لامية العرب للشنفرى أنموذجاYahya Saleh Hasan Dahami (يحيى صالح دحامي)No ratings yet

- Stories of Joseph: Narrative Migrations between Judaism and IslamFrom EverandStories of Joseph: Narrative Migrations between Judaism and IslamNo ratings yet

- Sufi Saint of The Sammaniyya Tariqa in IndonesiaDocument20 pagesSufi Saint of The Sammaniyya Tariqa in IndonesiaabusulavaNo ratings yet

- The Islamic Context of The Thousand and One NightsFrom EverandThe Islamic Context of The Thousand and One NightsRating: 1 out of 5 stars1/5 (1)

- Relocating Trans-National Trade and Cosmopolitan Diaspora in The Exploration of Muslim LivesDocument5 pagesRelocating Trans-National Trade and Cosmopolitan Diaspora in The Exploration of Muslim LivesAboobacker maNo ratings yet

- Matecconf Mucet2018 05054Document6 pagesMatecconf Mucet2018 05054muhamadNo ratings yet

- Waqf Distribution From Zanzibar To Mecca and MedinaDocument24 pagesWaqf Distribution From Zanzibar To Mecca and MedinarahimisaadNo ratings yet

- Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya in The "Lands Below The Wind" - Syamsudin ArifDocument31 pagesIbn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya in The "Lands Below The Wind" - Syamsudin ArifDimas WichaksonoNo ratings yet

- Nicholson. Orig & Devt of Sufiism. JRAS 38.2 (Apr 1906)Document47 pagesNicholson. Orig & Devt of Sufiism. JRAS 38.2 (Apr 1906)zloty941No ratings yet

- Ahmad Conversionsislamvalley 1979Document17 pagesAhmad Conversionsislamvalley 1979Vanshika SaiNo ratings yet

- India and Silk RoadDocument5 pagesIndia and Silk RoadAhmet GirginNo ratings yet

- 2 PDFDocument25 pages2 PDFJawad QureshiNo ratings yet

- From West Africa To Southeast Asia The HDocument4 pagesFrom West Africa To Southeast Asia The HAshir BeeranNo ratings yet

- Hindu-Muslim Relations in The Works of TagoreDocument19 pagesHindu-Muslim Relations in The Works of TagoreAparajay SurnamelessNo ratings yet

- Key to al-Fatiha: Understanding the Basic ConceptsFrom EverandKey to al-Fatiha: Understanding the Basic ConceptsRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (8)

- Nostalgia and Radicalization - European Eye On RadicalizationDocument6 pagesNostalgia and Radicalization - European Eye On RadicalizationGuillermo Ospina MoralesNo ratings yet

- JAb Husn Tha Unka Jalwa NumaDocument1 pageJAb Husn Tha Unka Jalwa NumaISRAR FARIDNo ratings yet

- The Life, Personality and Writings of Al-Junayd PDFDocument316 pagesThe Life, Personality and Writings of Al-Junayd PDFAboumyriam Abdelrahmane100% (3)

- Brief Biography of Hazrat Sirajuddin Junaid Baghdadi GulbergaDocument17 pagesBrief Biography of Hazrat Sirajuddin Junaid Baghdadi GulbergaMohammed Abdul Hafeez, B.Com., Hyderabad, IndiaNo ratings yet

- Soal Uts Bahasa Inggris Kelas 4Document4 pagesSoal Uts Bahasa Inggris Kelas 4Nyimas NurqomariahNo ratings yet

- Islamic (Hijri) Calendar Year 2022 CE: Based On Ummul Qura System, Saudi ArabiaDocument7 pagesIslamic (Hijri) Calendar Year 2022 CE: Based On Ummul Qura System, Saudi ArabiaSOE RestaurantNo ratings yet

- Latihan Menulis Nama Huruf BesarDocument28 pagesLatihan Menulis Nama Huruf BesarDel PirezNo ratings yet

- The Revolution of Al-Hussein (A) - It's Impact On The Consciousness of Muslim SocietyDocument197 pagesThe Revolution of Al-Hussein (A) - It's Impact On The Consciousness of Muslim SocietydishaNo ratings yet

- Mughal PaintingDocument5 pagesMughal PaintingAnamyaNo ratings yet

- Group 6 Main Reasons For Conflicting RulingsDocument150 pagesGroup 6 Main Reasons For Conflicting RulingsAndrea IvanneNo ratings yet

- Main Articles:, And: Byzantine-Sassanid War of 602-628 Fall of Sassanids Muslim Conquest of PersiaDocument6 pagesMain Articles:, And: Byzantine-Sassanid War of 602-628 Fall of Sassanids Muslim Conquest of PersiaAnonymous d6GqTk5wNo ratings yet

- Pronouncing ArabicDocument3 pagesPronouncing ArabicRoni Bou SabaNo ratings yet

- Year 4 WorkbookDocument46 pagesYear 4 WorkbookAfrah syed4ANo ratings yet

- Military Resistance 10H2: The Cuffed SleevesDocument30 pagesMilitary Resistance 10H2: The Cuffed Sleevespaola pisiNo ratings yet

- 1st NAT 2017 Form PDFDocument4 pages1st NAT 2017 Form PDFnziiiNo ratings yet

- The Art of TajweedDocument266 pagesThe Art of TajweedAbdullah Rahim Roman0% (1)

- Rationale Behind The Prohibition of Riba in IslamDocument5 pagesRationale Behind The Prohibition of Riba in IslamNatalia Qadira100% (1)

- Theories Stage 2 (Working Experience)Document9 pagesTheories Stage 2 (Working Experience)Sid MurshidNo ratings yet

- Rafiq e Rozgar PDF DownloadDocument3 pagesRafiq e Rozgar PDF Downloadsuleman75% (4)

- Fin Insha by Syed Mohiuddin Qadri ZoreDocument119 pagesFin Insha by Syed Mohiuddin Qadri ZoremghsolutionsNo ratings yet

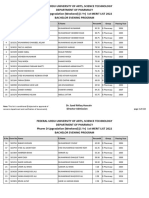

- Admission 2022 Bachelor 1st Merit List WebDocument113 pagesAdmission 2022 Bachelor 1st Merit List WebHafiz Muhammad Usman UsmanNo ratings yet

- List of Candidates From NON UE Countries Who Have Received Letter of Acceptance English Module 2019 2020Document3 pagesList of Candidates From NON UE Countries Who Have Received Letter of Acceptance English Module 2019 2020HcYeb KahnNo ratings yet

- Peran Spiritual Bagi Kesehatan Mental Mahasiswa Di Tengah Pandemi Covid-19 Desti AzaniaDocument20 pagesPeran Spiritual Bagi Kesehatan Mental Mahasiswa Di Tengah Pandemi Covid-19 Desti AzaniaIsnatainiNo ratings yet

- MANAJEMEN PENGELOLAAN MASJID - Part1Document2 pagesMANAJEMEN PENGELOLAAN MASJID - Part1PD PONTREN KABMGLNo ratings yet

- One Event of Hazrat Junaid of BaghadadDocument4 pagesOne Event of Hazrat Junaid of Baghadadfatima atherNo ratings yet

- Anchoring SpeechDocument10 pagesAnchoring SpeechHarsh M. Naik100% (1)

- CV MTRDocument8 pagesCV MTRMijanur RahmanNo ratings yet

- Nullity of Marriage in Malaysia, England and New Zealand: Comparative StudiesDocument21 pagesNullity of Marriage in Malaysia, England and New Zealand: Comparative Studiesnur athiraNo ratings yet

- Islam and Sacred SexualityDocument17 pagesIslam and Sacred SexualityburiedcriesNo ratings yet

- History Sec2Document23 pagesHistory Sec2Kerwinis TurningEmoNo ratings yet

![The Path of God's Bondsmen from Origin to Return [translated]](https://imgv2-1-f.scribdassets.com/img/word_document/271092473/149x198/13ba3ae696/1617224434?v=1)