Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Picturizing Sciencethe Science Documentary As Multimedia Spectacle

Uploaded by

Melissa CioacaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Picturizing Sciencethe Science Documentary As Multimedia Spectacle

Uploaded by

Melissa CioacaCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/249744232

Picturizing scienceThe science documentary as

multimedia spectacle

Article in International Journal of Cultural Studies · March 2006

DOI: 10.1177/1367877906061162

CITATIONS READS

37 1,959

1 author:

José Van Dijck

University of Amsterdam

145 PUBLICATIONS 7,053 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Platform Power View project

All content following this page was uploaded by José Van Dijck on 17 December 2014.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

International Journal of Cultural

Studies

http://ics.sagepub.com

Picturizing science: The science documentary as multimedia spectacle

Josè van Dijck

International Journal of Cultural Studies 2006; 9; 5

DOI: 10.1177/1367877906061162

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://ics.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/9/1/5

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for International Journal of Cultural Studies can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://ics.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://ics.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations (this article cites 7 articles hosted on the

SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms):

http://ics.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/9/1/5

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 5

ARTICLE

INTERNATIONAL

journal of

CULTURAL studies

Copyright © 2006 SAGE Publications

London, Thousand Oaks, CA and New Delhi

www.sagepublications.com

Volume 9(1): 5–24

DOI: 10.1177/1367877906061162

Picturizing science

The science documentary as multimedia spectacle

● José van Dijck

University of Amsterdam, The Netherlands

A B S T R A C T ● At the turn of the millennium, science documentaries show a

particular penchant for the abundant use of animated visuals, obviously

facilitated by new digital television techniques such as videographic animation

and computer animatronics. Analyzing two recent science documentary series

(Walking with Dinosaurs and The Elegant Universe) this article discusses how

scientists and television producers deploy digital animation to convince viewers

of the plausibility of scientific theories in the fields of paleontology and physics.

The question guiding these analyses is how the use of digital animation is

grounded in ambiguous epistemological and ontological claims. Rather than

lamenting the advancing pictorial effect and the demise of realism in

‘postmodern’ science documentaries, it is argued that the multimedia mix of

words, sounds and images both reflects and transforms our claims to knowledge.

In fact, science documentaries do not illustrate but enable scientific claims; they

visualize knowledge while substantiating hypotheses. ●

KEYWORDS ● cultural analysis ● digital animation ● narrative modes

● science documentary, television documentary ● visual styles

Introduction

After its initial launch in 1999, the BBC’s Walking with Dinosaurs became

an immediate hit with television audiences around the world, even if this

reinvigorated genre of the natural history documentary drew profound

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 6

6 I N T E R N AT I O N A L journal of C U LT U R A L studies 9(1)

criticism from renowned science commentators. At the heart of this criti-

cism was the complaint that digital animation overwhelmed documentary

intentions and that the series, despite its technical novelty, failed to offer a

‘new and improved’ approach to disseminating scientific knowledge. Others

resented the BBC’s claim to present an accurate vision of paleontology,

while favouring spectacle and edutainment at the expense of factual repre-

sentation and realism. Walking with Dinosaurs gave rise to a number of

academic inquiries, some of which called the series a ‘turning point’ in the

history of science documentaries (Darley, 2003; Jeffries, 2003; Scott and

White, 2003). British media theorist Andrew Darley (2003) disparaged the

documentary’s postmodern style and techniques, rhetorical approach, and

overall aesthetic orientation. Its most noted feature – the use of special

effects and computer animation – allegedly drives science producers’ affinity

for spectacle and edutainment further towards contemporary filmmakers’

preference for simulation, pastiche, and hyper-realism. According to Darley

(2003: 229) Walking with Dinosaurs exemplifies the so-called postmodern

science documentary, which falls prey ‘to contemporary aesthetic strategies

that tend to negate representation and meaning (content), promoting

instead the fascinations of spectacle and form (style)’.

Indeed, recent science documentaries show a particular penchant for the

abundant use of animated visuals, obviously facilitated by new digital tele-

vision techniques such as videographic animation and computer animatron-

ics. Computer engineers can create moving pictures out of pixels without

the necessity of an analogue referent – a technique that lends itself well to

illustrating abstract theories or speculative scientific hypotheses. However,

I disagree with Darley’s and other’s critique that

a) there is a sharp division or turning point between the so-called

modernist or realist paradigm in science documentaries and the post-

modernist or ‘fictionalist’ paradigm, and

b) that visual spectacle (‘form’) in this series overrules scientific claims to

knowledge (‘content’).

For one thing, science documentaries have never been objective populariza-

tions of science, but have always relied on realist (e.g. visual and narrative)

effects to convey the suggestion of trustworthiness and validity. Series like

Walking with Dinosaurs do not negate realism; on the contrary, one of the

series’ most remarkable features is its adherence to the dominant realist

paradigm, despite its abundant use of visual spectacle. Besides, the consti-

tutive role of visualizing technologies in contemporary science is nothing

new or disturbing; media technologies have never just served as tools for

dissemination or popularization, but have always actively shaped scientific

knowledge.

The current tendency to embellish science documentary with digital

‘pictorial’ techniques neither signals a break with the conventional genre,

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 7

van Dijck ● Picturizing science 7

nor does it imply a victory of form over content or aesthetics over science.

To support my claim, this article proposes a framework for analysing

science documentaries and natural history documentaries in terms of visual

and narrative rhetoric.1 The model typifies the science documentary as a

mixture of narrative modes and (tele)visual styles, the various combinations

of which help construct and sustain a particular claim to knowledge –

propositions of how things are, were, or could be. After applying this model

to Walking with Dinosaurs, a series intended to present a reconstruction of

prehistory, we will turn to another recent documentary series, The Elegant

Universe, and extend the analytical model to the representation of an

abstract and speculative branch of science: theoretical physics. It will be

argued that these documentaries’ truly remarkable feature is less their heavy

use of visual aesthetics and animatronics than their prolonged reliance on

conventional realist effects. Moreover, these analyses aim at disclosing how

visual styles and narrative modes are constitutive, rather than illustrative,

elements in the production of scientific claims to knowledge.

Narrative modes and visual styles in science documentaries

Science documentaries made for television have a longstanding tradition of

realism, a tradition cemented in the narrative modes of explanation and

exposition, and displayed in the visual styles of realist footage, in some cases

complemented by symbolic images. They are historically characterized as

linear, expository, and didactic tales – features that were always regarded

as the benchmarks of quality science programs such as the British series

Horizon (BBC) and its American counterpart Nova (PBS) (Gardner and

Young, 1981: 177). Since the beginning of science programming, the big

challenge for television producers and scientists alike has been to reconcile

the inherent unruliness of science with the laws of visualization enforced by

a medium primarily valued for its ability to entertain a large audience with

moving images. Much of science seemed to be unsuitable for television: its

disciplinary content was either too abstract (physics) or too theoretical

(mathematics), its subject matter too remote in time (prehistory) or place

(cosmology), its research object too infinitesimal (molecular biology) or

inaccessible (genetic therapy) for cameras to convey ‘realistic’ images. In

past decades, technologies for scientific imaging and televisual recording

have yielded impressive new views, including, for instance, the endoscopic

camera that can film inside our bodies and the satellite transmission

enabling real time images from other planets (van Dijck, 2005). Yet despite

television’s grateful incorporation of every new imaging instrument for the

purpose of popularization, there will always remain scientific areas that

resist ‘realistic’ visualization. In order to show the imperceptible and to

render the invisible imaginable, television producers, from the very onset,

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 8

8 I N T E R N AT I O N A L journal of C U LT U R A L studies 9(1)

have wielded an array of visual and rhetorical strategies to visualize and

narrate what science can never show and tell.

Arguably still the dominant storytelling strategy in science documentaries

today is the coupling of expository and explanatory modes of narrative with

realistic and metaphorical visual styles.2 In this hierarchical constellation,

visual modes are subjugated to the authority of the narrative mode – words

reign over visuals. The expository mode in its most prototypical form

consists of a voice (or voice-over) explaining what a scientific idea,

paradigm, or discovery entails. Frequently, this voice is embodied by a scien-

tist, who may also serve as the host of the program. An invisible, anony-

mous voice-over can be alternated by on-camera expositions of scientists,

whose authority is an indispensable asset to this narrative mode. Viewers

are more likely to trust claims made by the very persons who researched

them and whose authority is institutionally legitimate. Closely related to the

expository mode is the method of explanation: someone clarifying how

science works. Not all brilliant scientists are also good teachers; it is there-

fore quite common for television producers to rely on voice-overs for this

specific task. Elucidation commonly involves the use of rhetorical strategies

to enhance public understanding of scientific processes. Metaphors or

analogies are universal tools for explanation, but they are also directive

instruments, attaching quotidian, ideological, or political meanings to scien-

tific subjects (Bucchi, 1998; Nash, 1990; van Dijck, 1998). The explanatory

mode encompasses many rhetorical strategies: from metaphors to personal

stories by scientists, from detailed instructions by technicians to historical

excursions. Obviously, the more ‘visualizable’ the explanation, the better.

Within the realist paradigm of science documentary, expository or

explanatory modes are often stitched onto video footage showing actual or

symbolic events to produce a realistic or metaphorical effect. Much of

science can be captured on film: if you want to show at what temperature

ice melts, or if you want to demonstrate what threat forest fires pose to the

animal population, you go film where the action is. Film or video footage

of ‘science in action’ or ‘scientists at work’ is often used in connection to

shots of scientists talking on-camera, enhancing the expository mode. When

the subject matter prohibits realistic filming, producers often resort to

metaphoric visualization; shots of common objects, processes, or events are

linked to scientific ideas by means of analogy. For instance, in order to visu-

alize geneticist David Suzuki’s explanation of genetic mutation in his eight-

part documentary series The Secret of Life (1993), directors used the

extended metaphor of the ‘language of life,’ filming Suzuki sitting amidst

stacks of printed pages, archives, and endless rows of books in libraries.

Visual metaphors, like textual ones, are never neutral conduits for science,

but are attempts to attach concrete, everyday meanings to theoretical ideas

or scientific assumptions. Symbolic images are quite compatible with video

footage of ‘real’ science and scientists and they hardly compromise the

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 9

van Dijck ● Picturizing science 9

reality effect; particularly if coupled onto an explanatory narrative mode,

the metaphorical effect enhances rather than interferes with the illusion of

reality.

The two narrative modes (expository and explanatory) and televisual

styles (realistic and metaphorical) together inform what I will call the ‘realist

paradigm’ in science documentary – the most important markers of quality

science programming produced by institutions like the BBC and PBS in the

past 50 years. Western media still celebrate science’s foundation in empiri-

cism and positivism – the notion that all knowledge derives from observa-

tional experience – and grounds this foundation in the conventions of

electronic-realistic representation. The scientific claim of film and video to

observational truth, according to Brian Winston (1995: 137), is built into

the media apparatus as well as inscribed in the documentary genre: ‘The

documentary becomes scientific inscription – evidence.’ Science documen-

tary’s reality effect is rooted in technology and cultural form – a contract

between makers and viewers pertaining to visual recording devices that

inscribe ‘what science is’ or ‘how it works’. Even though this contract is

knowingly compromised by scripts, post-production editing, camera angles,

and a host of technical-rhetorical devices, they do not infringe on the agree-

ment between image and viewer. As Roger Silverstone (1985: 178) sums up

cogently: ‘The plausibility of a documentary film lies in its naturalization,

in its internal coherence and in its matching of its own reality to a reality

which ‘everyone knows.’ Quite a few cultural theorists and social construc-

tivists have pointed to suggestive, symbolic images that help construct scien-

tific claims in documentaries as ‘truth’ rather than as hypotheses or claims

to knowledge (Gardner and Young, 1981; Hornig, 1990). These criticisms

particularly pertain to the natural history documentary, a (sub)genre which

set the standard for the presentation of science on television both in terms

of content and style (Jeffries, 2003). Detractors contend it is precisely the

misleading combination of narrative authority and symbolic or metaphoric

images that renders these documentaries’ claims to veracity and accuracy

controversial (Crowther, 1997; Haraway, 1989).

In the past 25 years, however, the realist paradigm in science documen-

tary has been compromised each time innovative (tele)visual styles and

expansive narrative modes were pushed to the fore, forcing documentary-

makers to adjust their means of storytelling if they wanted to appeal to an

audience increasingly acculturated by Hollywood productions. The per-

ennial unattractiveness of the documentary form was that it could not tell

past stories, and neither could it speculate about consequences or impli-

cations, due to a lack of ‘real’ footage that might serve as evidence to a

voice-over or interviewee. In science documentary, particularly, the need for

reconstruction and speculation was poignant because scientific discoveries

were never captured in real time, and the relevance of many scientific

discoveries and claims lay in the future – applications that had yet to

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 10

10 I N T E R N AT I O N A L journal of C U LT U R A L studies 9(1)

emerge. Showing historical triumphs of science on television was inherently

difficult if one could not resort to the techniques of fiction: the only suitable

form in the realist mode was the talking head of a reminiscing scientist,

looking back on ‘what happened’ at this memorable moment. By the same

token, only legitimate spokespersons were authorized to speculate on the

future of particular developments in science. Yet none of these modes was

even remotely attractive without accompanying moving images. Whereas

photographic stills of historical events and symbolic shots of potential

implications could fill some of that void, the visual styles of fiction film

substantially increased the narrative potential of television documentary.

Documentary television producers, when first using reconstructive and

speculative modes, came under fire when they started to use these modes in

conjunction with a new visual style that allegedly breached the contract

between image and viewer. After the American evening news had included a

reenactment in one of its news features – a scene played out by actors in an

actual environment – critics and scholars lamented the beginning of a

downward spiral of trustworthiness.3 As more film-makers followed suit and

incorporated the ‘fiction effect’ into the documentary genre, science documen-

tary makers adopted this style to enhance the reconstructive mode (Winston,

1995: 254–5). BBC producers asked scientists to ‘re-enact’ or play out scenes

to show how important scientific discoveries had materialized. For instance,

a biologist agreed to restage her voyage through the Australian desert, where

she first got her brilliant insight in plant genetics when her car got stuck after

a sand storm messed up the fuselage. Scientists, initially weary that their being

drafted into professional acting would compromise their serious status, even

if playing former versions of themselves, were persuaded by the increased

dramatic appeal of science programming. After 1980, BBC and PBS science

documentaries increasingly included reenactments and staged scenes, visual

styles that greatly expanded the creative possibilities of producers and direc-

tors. Series like Horizon and Nova even embraced popular hybridizations like

docu-drama to enliven historical episodes of science, such as a reconstruction

of the double helix discovery by Watson and Crick (Franklin, 1988). Re-

enactments, however, were almost invariably paired off with the authorita-

tive expository mode, often voiced through a reminiscing scientist. As a result,

the fiction effect was made subordinate to the reality effect.

Besides reenactments becoming an accepted visual style in science docu-

mentaries, we can more recently witness an increasing use of digital anima-

tions to embellish this genre, causing what has also been called the ‘pictorial

effect’ (Mitchell, 1992). Naturally, pictures and animation have always been

used in science documentaries to visualize abstract projections, yet

drawings, diagrams, flow charts, or cartoon-like illustrations always explic-

itly signalled their artificiality and accentuated their animated quality. With

the emergence of digital video, we are witnessing a new type of ‘picturiz-

ing’: videographic animation and computer animatronics allow computer

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 11

van Dijck ● Picturizing science 11

engineers to create moving images out of pixels that look like analogue

video footage. In other words, digital videographics takes analogue video

footage as its benchmark for reality, whereas the truth-claim for video

footage was rooted in its verisimilitude. For producers of science documen-

taries, the use of digital video animations appears to be particularly fruitful

in areas that conventionally resist visualization, such as the very abstract,

remote, or inaccessible. In combination with the speculative mode, pictur-

ization allows visual substantiation of conditional, hypothetical, or even

speculative scientific claims stating ‘this could have happened in the past’

or ‘this is what could happen, if . . .’. This new visual style, in connection

to the speculative mode, again expands the potential of rhetorical strategies

for science documentary producers.

The pictorial effect, though, should be viewed in the context of its

ubiquitous implementation in visual culture; its smooth incorporation into

the science documentary cannot be seen apart from the abundant use of

videographics and digital animation in all sorts of audiovisual genres. The

immense quantity of digitally generated images in Hollywood productions,

from Batman to Jurassic Park, as well as in video games like Lara Croft,

have undoubtedly whetted the appetite and facilitated the acceptance of

videographic embalming in science documentaries. Images are becoming

more artefactual objects and pictures, not replications of the real, and their

accumulation in audio-visual productions has an overwhelming aesthetic

connotation, rather than a truthful or illusionist one (Cubitt, 2004). As digi-

tization enables near-perfect imitation of video footage, the pictorial effect’s

prominence is augmented in relation to the reality effect, the metaphorical

effect, or the fiction effect.

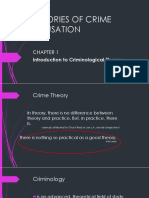

Let me reiterate in a schematic fashion the various styles and narrative

modes we have identified so far.

Visual styles Narrative modes

Film/video footage Reality effect Expository mode ‘this is what science is’

Symbolic visuals Metaphoric effect Explanatory mode ‘this is how science

works’

Reenactments Fiction effect Reconstructive mode ‘this is what happened’

Digital animations Pictorial effect Speculative mode ‘this is what could

(have) happen(ed)’

Figure 1 Visual styles and narrative modes

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 12

12 I N T E R N AT I O N A L journal of C U LT U R A L studies 9(1)

The upper and lower blocks in the diagram may seemingly ground the

televisual mediation of science in a realist vis-à-vis a fictionalist paradigm

(or, for that matter, the assumed modernist versus postmodernist scheme).

However, none of the visual styles or narrative modes distinguished in this

diagram is intrinsic to one specific type of documentary. Within the realist

paradigm, re-enactments and digital animations are commonly used to back

up specific explanations. Even before the implementation of digital tech-

nologies in science documentaries, producers regularly deployed pictorial

effects and speculative modes to embellish scientific claims. Now that the

speculative mode is taking prominence, science programs effectively incor-

porate elements of the realist paradigm to affirm their documentary status.

In other words, the two halves of this diagram are mutually dependent: it

is the actual combination of styles and modes that helps build powerful

rhetorical claims to knowledge in television documentaries.

The following will illustrate the intricate interweaving of visual styles and

narrative modes when analyzing two examples of recent science documen-

taries. Walking with Dinosaurs takes the reconstructive mode as a point of

departure as it re-animates extinct species from prehistory; The Elegant

Universe assumes the speculative mode to explore the highly abstract and

hypothetical subject matter of ‘string theory’. This layered model is not

aimed at identifying distinctive technical and aesthetic features of these

documentaries as if they intrinsically defined the genre; instead, it offers a

framework for analyzing how these documentaries’ respective claims to

knowledge are constructed through various combinations of narrative

modes and visual styles, thereby using innovative fictional techniques while

heavily relying upon realist conventions.

The reconstructive mode: Walking with Dinosaurs

There are scenes that really are very good science and there are those which

are more speculative, like mating. How on earth will we ever know how

dinosaurs mated? We’re not always showing people stuff that we know is

right, we’re showing people our best guess. (Tim Haines, producer of

Walking with Dinosaurs)

When Walking with Dinosaurs was first aired in 1999, the six-part series

was advertised by the BBC as ‘a window on the lost world’ allowing viewers

to ‘believe they were watching living creatures in their natural habitat’.

Digital animations of the Tyrannosaurus rex, the Optalmosaurus,

Stegosaurus and a number of other prehistoric animals populating planet

earth 65 million years ago, vivified paleontologists’ research by visualizing

their claims on our television screens. Like its sequel Walking with Beasts

(2001), this series popularized a somewhat dusty academic discipline to an

audience substantially younger than the average science documentary

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 13

van Dijck ● Picturizing science 13

viewer (Scott and White, 2003). The success of Walking with Dinosaurs

was primarily due to its technological production mode – the use of digital

animations and animatronics – cleverly hooking into a new cinematic

tradition established by Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993) and The

Lost World (1997). While the BBC adopted some of the visual styles

wielded in these Hollywood blockbusters, it strategically framed the series

as a natural history documentary. The ‘reality effect’ of Walking with

Dinosaurs lies in its ability to make a hypothetical reconstruction from the

past, produced entirely in fictional and pictorial styles, subservient to the

explanatory and expository narrative modes, anchoring animated fiction in

the realist paradigm of science documentary.

Walking with Dinosaurs utilizes three different types of visuals. First,

there is the footage of landscapes, filmed in Chile, California, and New

Caledonia – not because the prehistoric animals presumably lived there, but

because these sceneries resemble the biotope of dinosaurs at the time:

sparsely vegetated steppe without grass. Secondly, there are scenes in which

specially constructed clay models of creatures serve as props in close-up

shots.4 These models are like puppets set in motion by people and machines;

in the editing stage, these props were digitally manipulated to make them

walk, eat, or move ‘correctly’, that is, according to scientific conjectures.

Finally, there are scenes that are generated entirely by digital animatronics.

Animated creatures and filmed models all seamlessly merge with their

‘natural habitat’, blending into a single visual style: the realist style of a

natural history documentary. Enhancing the realist effect are shots marking

the unobtrusive presence of an ‘actual’ camera crew: the camera lens gets

accidentally clouded by a mating dinosaur’s saliva, or gets speckled by water

drops when two animals are fighting.

Undoubtedly the most notable feature confirming Walking with

Dinosaurs’ genre label is its narrative mode of explanation. A neutral, invis-

ible voice-over comments on every scene as if it is taking place in real time,

explaining in the present tense how dinosaurs go about daily acts like

eating, mating, surviving: ‘A young male tries to attract the attention of a

female by walking next to her, but mating can be a dangerous act for the

female Diplodocus.’ As Scott and White (2003: 321) have noticed, the

voice-over impersonates ‘an authoritative commentary by an omniscient

narrator, combining the “objective” discourse of scientific knowledge (facts

and figures) with touches of anthropomorphism’. The voice-over firmly

anchors the series in the narrative mode of explanation, but more than that,

it articulates the reconstructive mode (‘this is what assumedly happened’)

in the typical linguistic features of real-time exposition (‘this is what

happens’). Reconstruction and speculation hide behind an expository sheen

of realistic visuals authenticated by a mixture of voice-over, ‘real-time’

(fabricated) sounds of animals, and background music to accentuate tense

or romantic moments. It is exactly this mixture of scientific reconstruction

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 14

14 I N T E R N AT I O N A L journal of C U LT U R A L studies 9(1)

and speculative imagination that turns Walking with Dinosaurs into attrac-

tive television, but this very blend also subverts the contract between maker

and viewer as to what the images actually show.

Part of the series’ claim to authentication (or scientific reconstruction) is

made not in the documentary itself, but in the accompanying The Making

of Walking with Dinosaurs series. The meta-documentary recounts how

100 scientists were involved in this monster production. Indeed, the involve-

ment of scientists in television documentaries is nothing new, as scientists’

participation in Hollywood (science) fiction is now the rule rather than the

exception (Frank, 2003). In line with the conventions of the natural history

documentary, no scientist appears on camera in the documentary proper;

yet in The Making of Walking with Dinosaurs, they have ample opportunity

to show off their authority and validate the program’s claim to scientific

truth. Paleontologists explain head-on what evidence they found to substan-

tiate their claims, before properly instructing computer engineers how to go

about ‘animating’ the models. Sometimes the skeletal structures of living

animals, such as elephants, were used to teach engineers and scientists about

the most likely locomotion of prehistoric beasts. But The Making of

Walking with Dinosaurs also reveals that not just paleontologists served to

guarantee the accuracy and veracity of the series’ scientific claims; media

technicians and animation experts were actively engaged in scientific work.

Technicians sometimes refuted accepted knowledge in paleontology because

their models showed a specific locomotion to be impossible. As one scien-

tist comments in the programme, paleontologists actually learned from

animation programmers because they helped them ‘prove’ how the

Diplodocus walked, how it moved its legs and arms, how the animals grazed

and fought. The Making of Walking with Dinosaurs, in addition to illus-

trating how the series was made, also shows how science is made: tech-

nicians help scientists establish their claims by using the very tools that turn

them into attractive spectacle.

What makes this meta-documentary so important, in my view, is the

observation that its prominent visual style (animation) is no longer used as

an illustration, but that computer graphics are an integral part of construct-

ing science – an observation made earlier by social constructivists and

philosophers of science (Latour, 1990; Lynch and Woolgar, 1990). Models

and representations visually melting into a seamless whole demonstrate how

scientific claims are intrinsically dependent upon their visualizations.

Computer animations are concurrently instruments of mediating and

constructing science. The pictorial effect, serving to ‘authenticate’ the real-

istic effect, is part of the scientific process, which is at the same time and

by the same means a creative process to turn science into television. Visu-

alization and scientific argumentation are mutually contingent. As this series

seems to sustain, digital ‘picturization’ is not just an effect but a constitu-

tive tool of science. Meanwhile, the series Walking with Dinosaurs derives

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 15

van Dijck ● Picturizing science 15

much, if not all, of its scientific trustworthiness from its unarticulated

framing as a realist documentary, in which voice is supposed to reign over

visual. The reconstructive mode seems merely ‘illustrated’ by digital effects

and animation, assuming its subordination to the conventional narrative

modes of exposition and explanation. However, my interpretative analysis

reveals this to be an effective rhetorical tactic aimed at anchoring the docu-

mentary’s truth-claims in accepted realist conventions.

The speculative mode: The Elegant Universe

The decision to use animation, to use a lot of it, was completely essential to

the process, because when you’re doing that project about string theory, when

you’re talking about things that really cannot be seen, that can only be

imagined, I don’t know any other way to do it than through metaphor and

animation. (Paula S. Apseil, senior executive producer of The Elegant

Universe)

A similar blend of realist claims to scientific truth and animated visual

aesthetics can be traced in a science programme that is primarily informed

by the speculative mode. The Elegant Universe, a three-part documentary

series aired by PBS in 2003, manages to make a very difficult, highly

abstract and hypothetical subject from the field of theoretical physics imag-

inable to laypersons. The world of string theory – ‘a world stranger than

science fiction’ according to the PBS announcement – conjectures a

reconciliation of Isaac Newton’s laws of gravity, Albert Einstein’s discover-

ies on relativity, Niels Bohr’s findings in quantum mechanics, and James

Maxwell’s mathematical equations describing electro-magnetism into a

unified ‘theory of everything’. String physicists assume the existence of a

subatomic level where ‘strings’, entities smaller than particles or quarks,

generate a variety of shapes, from black holes to membranes. An import-

ant tenet of string theory is the existence of not 4, but 11 dimensions –

dimensions that we cannot see or even make visible – and a possible infinite

number of parallel universes. It claims to bring together the divergent sets

of laws formulated by famous physicists, and also prophesies a coherent

explanation for all manifestations of matter now and in the future. As Brian

Greene, physicist at Columbia University and host of The Elegant Universe

suggests, questions of philosophy or religion may soon become questions of

physics. String theorists’ hypotheses are, not surprisingly, fiercely disputed

amongst scientists, but how does this television documentary render their

claims plausible and even likely?

The overwhelming use of digital animation and videographics in this

series is partly responsible for a persuasive presentation of a contentious

theory, but its scientific claims are ultimately validated by the explanatory

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 16

16 I N T E R N AT I O N A L journal of C U LT U R A L studies 9(1)

mode. In contrast to Walking with Dinosaurs, The Elegant Universe relies

on the conventional narrative strategy of an expert commentator. Host Brian

Greene is an authority in the field and an engaging storyteller who lucidly

explains the most difficult concepts by means of metaphors and analogies.

He uses a cello to explain string vibrations, an analogy between a cup of

coffee and a donut to illustrate the significance of shapes, and sliced bread to

exemplify the existence of parallel universes. But Greene’s explanatory narra-

tive is never simply illustrated by pictures of everyday objects; all images, even

those of the host himself, are choreographed into fast-paced animated

sequences, to such an extent that it is impossible to distinguish video footage

from morphing animations, or material objects from pictorial metaphors.

For instance, Brian Greene’s talking head appears on a slice of bread that he

himself is cutting; in the same visual style, a cup of coffee digitally morphs

into a donut. Even textual inserts, such as mathematical formulas or letters

(G for gravity, EM for electromagnetism) smoothly change into visuals, just

as the sound of strings transforms into images. To enhance the explanatory

mode, Greene’s words are frequently alternated by single quotes from an

impressive parade of top-notch physicists. Initially, their talking heads appear

in straightforward on-camera interviews, their authority signalled by name,

title, and institutional affiliation.5 But in subsequent scenes, their images are

retouched to appear for example on large screens over Broadway or, when a

scientist explains the existence of more dimensions, the screen shows his

multiple faces. Animations ‘hijack’ the explanatory mode, subjecting all

video footage to the elasticity of digital graphics; the hypothesized universe

of string theory seems already real in the world of multimedia, where text,

sound, video footage, and animation all merge into a unified visual style.

For the large part, The Elegant Universe relies on the speculative mode,

yet it also includes reconstructive parts in which historical events are re-

enacted, suggestively lacing history onto the future. Standing in the

doorway of what used to be Einstein’s house in Princeton, New Jersey, Brian

Greene recounts the legend of how this famed scientist chased the holy grail

of physics until he ran out of time. Various milestones in the history of

physics are re-enacted, suggestively pairing off historical geniuses with the

brilliant minds of string theorists today. The story jumps back and forth

between Niels Bohr working in his office and John Schwarz, one of the early

advocates of string theory in 1973, anxiously pacing in front of a black-

board filled with formulas; between an impersonated Caluzzo in debate

with Einstein, and Ed Witten, whose 1995 paper reconciling various strands

of string theory secured him the epithet of ‘Einstein’s successor.’ Reenacted

scenes can hardly be distinguished from black-and-white photographs,

retouched and animated to make them look like historical footage, and

actual video footage projected in slow motion is frequently interrupted by

visual tricks, like formulas leaping off a blackboard. In several instances,

the viewer is catapulted from the history of physics straight into the future.

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 17

van Dijck ● Picturizing science 17

After recapturing Einstein’s discovery of how space can stretch and warp,

host Brian Greene explains how string theory can also account for space

being ‘ripped apart’ so that an extra dimension becomes feasible. A proven

theory is thus equated with a current hypothesis, and subsequently stitched

onto a prediction of future implications. ‘Can you walk on the Mount

Everest, eat a baguette in Paris, and still be back in New York on time for

your morning meeting?’ Greene ponders, while his movements are smoothly

sealed onto morphing backdrops. Past, present, and future – proven

theories, hypothetical claims, and speculation – all blend into the visual style

of an animated universe, where the differences between realism, fiction, and

science fiction appear virtually obsolete.

The Elegant Universe presents a multimedia spectacle which magically

turns hypothesis into feasibility, and speculation into proven claim. But does

the science represented in this documentary still pertain to questions of truth

and falsehood or, perhaps more relevant here, to representational criteria of

fact or fiction? Several detractors interviewed for the programme point out

the weakness of string theory: even if this theory will prove to be mathe-

matically sound, it can never be put to a test. Indeed, the programme’s host

Brian Greene admits that ‘testing’ string theory is impossible; even the giant

atom smashers, currently being built by Fermilab in Texas and by CERN

in Switzerland, will at best deliver circumstantial evidence for the existence

of strings, sparticles, or gravitons. And yet, throughout the program, Greene

subjects the laws of physics, along with the assumptions of string theory, to

‘experiments’ in virtual reality, executed in digital architecture. For instance,

when he wants to show how the laws of electromagnetism interfere with

the laws of gravity, Greene is filmed jumping from a tall building but magi-

cally landing on his two feet. This animated scene is, of course, an imita-

tion of a made-in-Hollywood Batman leap, constructed in such a style that

even if you don’t believe in the existence of flying human bats, you have to

admire the reality-effect caused by its visual artifice.

In the two-dimensional world of film and multimedia, the 11 dimensions

of string theory can at least be turned into a visual reality – a universe that

is governed by the rules of animation but subjected to the laws of verisimili-

tude and realism. Ultimately, the answer to the million-dollar question,

posed at the end of the series – ‘Can string theory be wrong?’ – is as simple

as it is revealing. Brian Greene philosophizes that so much of string theory

makes sense, ‘it has got to be right’, and his judgement is supported by

Nobel-prize-winning physicist Steven Weinberg, saying: ‘I find it hard to

believe that that much elegance and mathematical beauty would simply be

wasted.’ Ordinary viewers, overwhelmed by three hours of digital videog-

raphy, may find it hard to believe that the sophistication and elegance of

this multimedia spectacle would be wasted. Qualifications of verification

and trustworthiness are subtly replaced by qualifications of aesthetics and

persuasiveness.

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 18

18 I N T E R N AT I O N A L journal of C U LT U R A L studies 9(1)

And yet, despite its visual fireworks and aesthetic overload, the documen-

tary astonishingly relies on the authority of voice(-over) and words to

establish the trustworthiness of its claims. Like Walking with Dinosaurs, The

Elegant Universe includes reenactments and animations to ‘picturize’

scientific theory that is otherwise too abstract to be understood by non-

physicists. In addition, the speculative mode accounts for playful visual tricks

borrowed directly from fiction to enhance the documentary’s metaphorical

and pictorial effects. But it is the distinguished commentary and appearance

of physicist Brian Greene (supported by a large number of authorities in the

field) who, at all times, subjects the artificiality of images to the ‘authenticity’

of his words, much like the neutral voice-over in Walking with Dinosaurs

takes command of the animated pictures of conjectured prehistoric beasts.

Even if visual spectacle seems at times to overwhelm the rational content of

the science presented, it is in fact the rhetorical choreography of carefully

intertwined narrative modes and visual styles that ultimately grounds both

documentaries in a conventional realist paradigm. The authority and trust-

worthiness of its proposed scientific claims are ultimately contingent upon

the reality effect created by the documentary’s producers.

In the previous section, I explained how Walking with Dinosaurs, rather

than being a popularized version of paleontology, actually helped construct

its scientific claims – an observation that becomes particularly manifest in

The Making of Walking with Dinosaurs episode. Along similar lines, the

makers of The Elegant Universe, in the bonus material added to the DVD

version, comment on the crucial function of animatronics to the construc-

tion of string theory. Without the possibilities of computer animation there

would have been no documentary, but there also would have been no

theory: computer graphics enable scientists to imagine the possible shapes

the ‘materialist world’ can assume. In The Making of Walking with

Dinosaurs, producer Paula Apseil explains how the scientific claims of

string theory are contingent on new modes of visualization: ‘We could not

have told the story of string theory and we could not have visualized all the

aspects of the universe which string theory says could be true, if we would

not have used animation.’ For instance, the contention of string theorists

that the ‘big bang’ was not the beginning of evolution, and therefore that

history or space has no beginning or ending, is perfectly in tune with the

notion that visual images in this series lack an original in the real world.

Computers and multimedia environments have turned the world of science

into a large database of digital images, a database in which the footage does

not bespeak an original in the empirical world. Past, present, and future

claims are all ‘pictorial input’ ready for morphing: Einstein’s historical life

and ideas evolve into Brian Greene’s projected existence into parallel

universes. In fact, the multimedia representation of string theory does not

illustrate but enables its claims; it not only helps visualize, but to some

extent substantiates its hypotheses.

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 19

van Dijck ● Picturizing science 19

In the past, documentaries based in the realist paradigm seemingly

displayed science within the logical order of empiricism, affirming the

Platonic hierarchy between reality and representation, thus constituting the

mastery of words over visual illustration, of explanation over speculation,

and of reality over fiction. The linear order of history, the empiricist order

of science, and the representational order of science documentary were all

grounded in the same ontological claims: what likely happened in the past

or potentially happens in the future cannot be ‘authentically’ filmed, it can

only be illustrated by artificial means. Recent documentaries like Walking

with Dinosaurs and The Elegant Universe apparently subvert the

proclaimed ontological order between science and reality vis-à-vis represen-

tation and fiction. And yet, more than ever, the science documentary relies

on the presence of realist features, such as an authoritative voice-over, a

well-respected host, or the appearance of an impressive number of experts

in the field, to anchor its claims to trustworthiness in the realist paradigm.

The science documentary, while subverting its own ontological claims, para-

doxically affirms the hierarchy of ‘science’ over ‘fiction’, of ‘content’ over

‘spectacle’, and of ‘popularization’ over ‘construction’.

Conclusion

Many academics and commentators, like Andrew Darley (2003: 229)

conclude that documentaries like Walking with Dinosaurs, and by exten-

sion The Elegant Universe, emanate from a cultural context that favours

simulation and hyper-realism, and therefore negates realism. Darley and

others observe a sharp turning point between the evidently modernist (or

realist) and postmodernist (or fictionalist) documentary genre, the latter of

which is resented because its aesthetic strategies and high-tech visual spec-

tacle tend to overwhelm scientific content. Indeed, the technological is a

significant part of a larger cultural transformation that some have labelled

the ‘postmodern condition’ (Harvey, 1990; Lyotard, 1984). However, as I

have argued in this article, assuming an intrinsic divide between modernist

and postmodernist documentary genres may be ahistorical and insufficient

as a mode of criticism. Applying a model that distinguishes visual styles and

narrative modes, it becomes clear that the realist paradigm of science docu-

mentary, even in its earlier stages, incorporated fictional and pictorial styles

as well as speculative and reconstructive narrative modes. And vice versa,

while the multimedia spectacles produced by the BBC and PBS thrive on the

dominant modes of speculation and reconstruction, their status and author-

ity as science documentaries is ultimately contingent upon their use of

explanation and exposition. Every a priori distinction between modern and

postmodern, as Bruno Latour (1993) has convincingly argued, is epistemo-

logically flawed because it hinges on fallacious dichotomies between science

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 20

20 I N T E R N AT I O N A L journal of C U LT U R A L studies 9(1)

and representation, between scientific object and active agent, and between

science and culture. Latour’s argument that ‘we have never been modern’

also applies to the science documentary: there has never been a purely

‘realist’ paradigm in science programming.

Arguing from a somewhat different angle, John Corner (2002: 266) has

launched the term ‘postdocumentary’, not to proclaim the end of documen-

tary as a truthful cultural form, but to signal ‘its relocation as a set of prac-

tices, forms, and functions.’ He argues that the legacy of documentary is

still at work in current styles of televisuality, reaffirming the realist contract

between viewers and makers but concurrently subverting it in favour of

innovative claims to knowledge. Since digital technologies are changing our

ontological relationship with the image (Manovich, 2001), we need a more

refined analytical armamentarium to discuss the intrinsically mediated

construction of scientific knowledge. The model proposed in this article

provides such analytical tool, allowing viewers to recognize the construct-

edness of documentary texts. And yet, it is not enough to identify the

construction of documentaries; it is even more important to understand

how science and documentary are mutually contingent and interdependent

constructions of scientific claims.

Science documentaries never served as mere illustrations of what ‘science

is’ or ‘how it works’. The documentary’s status as a ‘popularization’ or an

‘illustration’ was taken for granted, but like any imaging tool used by

scientists, television is equally instrumental to the construction, dissemi-

nation, and (dis)approval of its often hypothetical claims. The popularity

of scientific claims is inevitably defined by the available technology and

preferred aesthetics of contemporary media – media that enabled the

construction of these claims in the first place. From Galileo’s telescope to

Etienne-Jules Marey’s stereoscope, tools of visualization have moved easily

between scientific investigation and entertainment (Hankins and Silverman,

1995; Topper, 1996). Therefore, I propose to consider science documen-

taries as a form of ‘visual thinking’ or of ‘picturizing science’. We do not

illustrate science with images, we construct images and deploy media tech-

nologies to ‘think’ science (Burnett, 2004). Computer graphics and anima-

tronics are to 21st century physicists and paleontologists what the

microscope was to 19th century biologists: new instruments allowing for

new claims, but also for a retooling of the imagination. Animated dinosaurs

and virtual parallel universes are not illustrations of science – they are part

of science in action.

Rather than lament the current effacement of science documentary’s

realism, we need to develop analytic models and tools that help clarify how

science and science documentaries shape our world in tandem. Computers

and digitization are certainly not a radical break with previous scientific

practices which were always also mediated practices: the success of scien-

tific claims often depended on the success of their visualizations. Analysis

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 21

van Dijck ● Picturizing science 21

of two recent science documentaries reveals how the constructions of

science and media are closely aligned and intricately intertwined. As argued

in this article, the pictorial effect and speculative narrative mode may infil-

trate and even dominate a television programme, and yet producers choose

to pay careful tribute to the realist features of the documentary genre. Even

the most radical deployment of the pictorial effect in The Elegant Universe

still results in a typical representationalist view of the world, as it anchors

its speculative claims in explanatory and expository modes to account for

the documentary’s evidentiary status. Its mixture of visual styles and narra-

tive modes signals the paradoxical yet imperative cohabitation of diverging

ontological paradigms. More concretely, it demonstrates how a set of scien-

tific hypotheses (‘this is a possible theory to account for the existence of

parallel universes’ or ‘this is our best guess of how dinosaurs walked’) is

articulated in a set of televisual claims to truth (‘this is what string theory

is’ or ‘this is how dinosaurs walked’). Perhaps more interesting than iden-

tifying or lamenting the postmodern genre of science documentary is to

examine how the multimedia mix of words, sounds, and images transforms

our claims to knowledge.

Science documentaries offer a unique opportunity to bare scientists’ and

media producers’ struggles with old and new epistemological and ontologi-

cal paradigms. Replacing attenuated realist claims of what science is, how

it works, how it happened, or what could happen, we should foreground

the question of how science (documentary) shapes our world. Towards that

end, The Making Of episodes accompanying these documentaries form an

integral part of the viewing experience: they teach viewers how technology

shapes both science and media, and demonstrate how programme makers

and scientists decide what to show, how to show it, and why to show it that

way. The science documentary is a meeting place for the didactic and the

scientific, the truthful and the elegant; yet it is precisely the awe-inspiring

presence of accredited scientists or the overwhelming elegance of multi-

media spectacles that obligate viewers to acknowledge its contents’ strati-

fied texture.

Acknowledgement

I would like to thank the anonymous referees of the International Journal of

Cultural Studies for their comments; they have helped to substantially improve

a previous version of this article.

Notes

1 This article will refer to the natural history documentary as a special subgenre

of the science documentary. Even though many relevant comments can be

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 22

22 I N T E R N AT I O N A L journal of C U LT U R A L studies 9(1)

made about the distinctions between these two, these differences are beyond

the scope of the main argument here.

2 I use the term ‘narrative mode’ to indicate that every science documentary –

or every television programme for that matter – tells a story about science

using a particular strategy, both in terms of rhetoric and in terms of aesthet-

ics. By ‘(tele)visual styles’ I mean the effects created by using a specific type

of image or image processing in relation to the truth-claim implied by that

choice. For instance, a realist effect is an effect that is implicitly ascribed to

unedited, unaltered video footage. Naturally, moving images of whatever

technological basis are always intrinsically contrived, but visual styles have

gradually come to connote particular effects.

3 In 1988, the ABC Evening News, for instance, used a re-enactment to recon-

struct how an American spy had probably managed to steal secret infor-

mation from a government building. For a detailed analysis of news

documentary, see Beattie (2004), chapter 9.

4 Construction of animated dinosaurs is a painstaking process, as we can read

on the website (http://www.bbc.co.uk/dinosaurs/tv_series/making_of.shtml):

‘Not every dinosaur image was computer-generated; many of the close-up

shots used animated models. This is because whilst computer graphics are

good, they are better for long distance shots. Animatronics are more realis-

tic in close up work, such as when a dinosaur is eating or drinking. Initial

models are made in clay, then a series of inverse moulds are made from which

the final product is produced. Textured skins are stuck on top and painted,

using a “plasticised” paint to allow for movement. Mounts are added for

handholds plus motors to operate the nostrils, eyes or other body parts.’

5 A large number of highly esteemed physicists appear in this programme. First,

there are the ‘grand old men’ of string theory: John Schwarz, Michael Greene,

and Ed Witten. Secondly, a number of authorities in various subdisciplines of

physics comment in this program, including Walter G. Lewin (MIT), Steven

Weinberg (Universty of Texas), Peter Galison (Harvard University), Alan

Guth (MIT), Joseph Polchinski (UC Santa Barbara), S. James Gates

(University of Maryland), and Michael Dugg (University of Chicago).

References

Beattie, K. (2004) Documentary Screens: Nonfiction, Film and Television.

Houndmills: Palgrave.

Bucchi, M. (1998) Science and the Media: Alternative Routes in Scientific

Communication. London: Routledge.

Burnett, R. (2004) How Images Think. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Corner, J. (2002) ‘Performing the Real: Documentary Diversions’, Television

and New Media 3(1): 255–69.

Crowther, B. (1997) ‘Viewing What Comes Naturally: A Feminist Approach to

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 23

van Dijck ● Picturizing science 23

Television Natural History’, Women’s Studies International Forum 20:

289–300.

Cubitt, S. (2004) The Cinema Effect. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Darley, A. (2003) ‘Simulating Natural History: Walking with Dinosaurs as

Hyper-real Edutainment’, Science as Culture 12(2): 227–56.

Frank, S. (2003) ‘Reel Reality: Science Consultants in Hollywood’, Science as

Culture 12(4): 427–69.

Franklin, S.B. (1988) ‘Life Story: The Gene as Fetish Object on TV’, Science as

Culture 1(1): 92–100.

Gardner, C. and R. Young (1981) ‘Science on TV: A Critique’, in T. Bennett (ed.)

Popular Television and Film, pp. 171–93. London: British Film Institute.

Hankins, T.J. and R.J. Silverman (1995) Instruments and the Imagination.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Haraway, D. (1989) Primate Visions: Gender, Race and Nature in the World of

Modern Science. New York: Routledge.

Harvey, D. (1990) The Condition of Postmodernity: An Enquiry into the

Origins of Cultural Change. Cambridge: Blackwell.

Hornig, S. (1990) ‘Television’s NOVA and the Construction of Scientific Truth’,

Critical Studies in Mass Communication 7(1): 11–23.

Jeffries, M. (2003) ‘BBC Natural History versus Science Paradigms’, Science as

Culture 12(4): 527–45.

Latour, B. (1990) ‘Drawing Things Together’, in M. Lynch and S. Woolgar (eds)

Representation in Scientific Practice, pp. 19–67. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Latour, B. (1993) We Have Never Been Modern. Cambridge, MA: Harvard

University Press.

Lynch, M. and S. Woolgar, eds (1988) Representation in Scientific Practice.

Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lyotard, J.-F. (1984) The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Knowledge.

Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Manovich, L. (2001) The Language of New Media. Cambridge, MA: MIT

Press.

Mitchell, W.J.T. (1992) The Reconfigured Eye: Visual Truth in the Post-

Photographic Era. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Nash, C., ed. (1990) Narrative in Culture: The Uses of Story-telling in the

Sciences, Philosophy, and Literature. London: Routledge.

Scott, K.D. and A.M. White (2003) ‘Unnatural History? Deconstructing the

Walking with Dinosaurs Phenomenon’, Media, Culture and Society 25:

315–32.

Silverstone, R. (1985) Framing Science: The Making of a BBC Documentary.

London: British Film Institute.

Topper, D. (1996) ‘Towards an Epistemology of Scientific Illustrations’, in B.S.

Baigrie (ed.) Picturing Knowledge: Historical and Philosophical Problems

Concerning the Use of Art in Science, pp. 215–49. Toronto: University of

Toronto Press.

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

01_vandijck_061162 (jk-t) 7/2/06 9:19 am Page 24

24 I N T E R N AT I O N A L journal of C U LT U R A L studies 9(1)

van Dijck, J. (1998) ImagEnation: Popular Images of Genetics. New York: New

York University Press.

van Dijck, J. (2005) The Transparent Body: A Cultural Analysis of Medical

Imaging. Seattle, WN: University of Washington Press.

Winston, B. (1995) Claiming the Real: The Documentary Film Revisited.

London: British Film Institute.

Audio visual references

Jurassic Park (1993) Director: Steven Spielberg. Based on a novel by Michael

Crichton.

The Lost World (1997) Director: Steven Spielberg. Based on a novel by Michael

Crichton.

The Elegant Universe (2003) Producers: David Hickman, Joseph McMaster and

Julia Cort. Host: Brian Greene. Part of the PBS series NOVA (WGBH

Educational Foundation). Premiered in the US on December 27, 2003.

The Secret of Life (1993) Host: David Suzuki. Eight-part documentary PBS

series (WGBH Educational Foundation).

Walking with Dinosaurs (1999) Producer: Tim Haines. BBC/Discovery/TV

Asahi co-production in association with Pro Sieben and France 3. Premiered

in Great Britain on 4 October, 1999.

The Making of Walking with Dinosaurs (1999) Producer: Tim Haines.

BBC/Discovery/TV Asahi. Aired October 11, 1999.

Walking with Beasts (2001) Producer: Tim Haines. Narrator: Kenneth Branagh.

BBC/Discovery. Aired October, 2001.

● JOSÉ VAN DIJCK is Professor of Media and Culture at the

University of Amsterdam and chair of the Department of Media Studies.

She is the author of Manufacturing Babies and Public Consent: Debating

the New Reproductive Technologies (New York University Press, 1995)

and ImagEnation: Popular Images of Genetics (New York: New York

University Press, 1998). Her latest book is titled The Transparent Body: A

Cultural Analysis of Medical Imaging (Seattle: University of Washington

Press, 2005). Her research areas include media and science, (digital)

media technologies, and television and culture. Address: Department of

Media Studies, University of Amsterdam, Turfdraagsterpad 9, 1012 XT

Amsterdam,The Netherlands. [email: j.van.dijck@uva.nl] ●

Downloaded from http://ics.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 12, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

View publication stats

You might also like

- Haeckel's Embryos: Images, Evolution, and FraudFrom EverandHaeckel's Embryos: Images, Evolution, and FraudRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (4)

- Don't Look Up Science Communicaiton RevisitedDocument8 pagesDon't Look Up Science Communicaiton Revisitedscribd.backtalk254No ratings yet

- Research Films in Biology, Anthropology, Psychology, and MedicineFrom EverandResearch Films in Biology, Anthropology, Psychology, and MedicineNo ratings yet

- Zoology 3d PDFDocument5 pagesZoology 3d PDFPrada MiguelNo ratings yet

- Astral Projection: Theories of Metaphor, Philosophies of Science, and The Art of Scientific VisualizationDocument291 pagesAstral Projection: Theories of Metaphor, Philosophies of Science, and The Art of Scientific VisualizationHerodotou ConstantinosNo ratings yet

- Image Evolution: Technological Transformations of Visual Media CultureFrom EverandImage Evolution: Technological Transformations of Visual Media CultureNo ratings yet

- ArDocument23 pagesArjulietastarNo ratings yet

- Introducing Science through Images: Cases of Visual PopularizationFrom EverandIntroducing Science through Images: Cases of Visual PopularizationNo ratings yet

- Science - 13 May 2022Document180 pagesScience - 13 May 2022Jean-Philippe BinderNo ratings yet

- Gunter Lösel: 1.1 Current State of Research and Discussion 1.2 Our Research Journey and This BookDocument14 pagesGunter Lösel: 1.1 Current State of Research and Discussion 1.2 Our Research Journey and This Bookjavi flowNo ratings yet

- Explore the Atlas of ScienceDocument34 pagesExplore the Atlas of ScienceDavid MukhamadeevNo ratings yet

- Transformation of The Media Landscape: Infotainment Versus Expository Narrations For Communicating Science in Online VideosDocument14 pagesTransformation of The Media Landscape: Infotainment Versus Expository Narrations For Communicating Science in Online VideosGross EduardNo ratings yet

- Artigo - A Life More Photographic Mapping The Networked Image - Daniel Rubinstein e Katrina Sluis (2008)Document22 pagesArtigo - A Life More Photographic Mapping The Networked Image - Daniel Rubinstein e Katrina Sluis (2008)Carolina RuizNo ratings yet

- Carusi MakingvisualvisibleDocument11 pagesCarusi MakingvisualvisibleJose Lozano GotorNo ratings yet

- From Science in Art To The Art of Science PDFDocument3 pagesFrom Science in Art To The Art of Science PDFDeniNo ratings yet

- Renewing Ethnographic Film MacDougallDocument8 pagesRenewing Ethnographic Film MacDougallnoralucaNo ratings yet

- Iwz 011Document10 pagesIwz 011Francisco DiasNo ratings yet

- A New Social Contract For ScienceDocument12 pagesA New Social Contract For ScienceanferrufoNo ratings yet

- Dudley Andrew - Core and Flow of Film Studies PDFDocument40 pagesDudley Andrew - Core and Flow of Film Studies PDFleretsantuNo ratings yet

- Scientist or Artist? Why Not Be Both?: World ViewDocument1 pageScientist or Artist? Why Not Be Both?: World ViewAnahí TessaNo ratings yet

- Interactive Science Museum DesignDocument13 pagesInteractive Science Museum Designchristian de leonNo ratings yet

- Popularizing Science and Nature Programm PDFDocument5 pagesPopularizing Science and Nature Programm PDFMilfor WolfpofNo ratings yet

- Evaluation of Touchable 3D Printed Replicas in MuseumsDocument21 pagesEvaluation of Touchable 3D Printed Replicas in MuseumsAndrej BassichNo ratings yet

- Photographies: A Life More PhotographicDocument21 pagesPhotographies: A Life More PhotographicVinit GuptaNo ratings yet

- SPECTRA-book-Learning Through Drawing in Art and ScienceDocument180 pagesSPECTRA-book-Learning Through Drawing in Art and ScienceDiego BetancourtNo ratings yet

- History of Science CommunicationDocument6 pagesHistory of Science CommunicationTom Camins CanoyNo ratings yet

- Nakoinz_Knitter_2016_ModellingHumanBehaviourinLandscapesDocument272 pagesNakoinz_Knitter_2016_ModellingHumanBehaviourinLandscapesAjAy Kumar RammoorthyNo ratings yet

- More Than Meets The Eyes Archaeology Under Water Technology and InterpretationDocument16 pagesMore Than Meets The Eyes Archaeology Under Water Technology and InterpretationFilippo MatucciNo ratings yet

- The Study of Suspense in Science and Education Documentary: An Interpretation Based On Text AnalysisDocument11 pagesThe Study of Suspense in Science and Education Documentary: An Interpretation Based On Text Analysisindex PubNo ratings yet

- Nature Magazine 7171 - 2007-12-06Document183 pagesNature Magazine 7171 - 2007-12-06Roberto KlesNo ratings yet

- Diss Jordt Underwater RecDocument245 pagesDiss Jordt Underwater RecElena DanilaNo ratings yet

- Belkand Kozinets Videographyand Netnography Chapter To ShareDocument19 pagesBelkand Kozinets Videographyand Netnography Chapter To SharePedro Pereira NetoNo ratings yet

- Toward an Archaeology of the ScreenDocument34 pagesToward an Archaeology of the ScreenB CerezoNo ratings yet

- Katalog 2014 SIYSSDocument17 pagesKatalog 2014 SIYSSPArk100No ratings yet

- Citizen Science Toolkit: BiodiversaDocument44 pagesCitizen Science Toolkit: BiodiversaEmilio DiazNo ratings yet

- Scientific Hangman: Gamifying Scientific Evidence For General PublicDocument8 pagesScientific Hangman: Gamifying Scientific Evidence For General PublicRicha GuptaNo ratings yet

- Science: GET Ready ForDocument16 pagesScience: GET Ready ForAnishNo ratings yet

- Bucher Niemann 2012 283.full With Cover Page v2Document26 pagesBucher Niemann 2012 283.full With Cover Page v2Lamees AbubakrNo ratings yet

- Tecnologias InteractivasDocument39 pagesTecnologias InteractivasGabriela CorralesNo ratings yet

- E-Conservation Magazine - 16Document76 pagesE-Conservation Magazine - 16conservators50% (2)

- Constructing A Digital Storycircle Digit PDFDocument18 pagesConstructing A Digital Storycircle Digit PDFHelmunthTorresContrerasNo ratings yet

- LEPOURAS Virtual MuseumDocument9 pagesLEPOURAS Virtual MuseumHelena Anjoš100% (1)

- 2008 Anker& TechnogenesisDocument47 pages2008 Anker& TechnogenesisENo ratings yet

- Immersive ProjectionDocument27 pagesImmersive ProjectionJônia RodriguesNo ratings yet

- Osci Interimreport 2012 PDFDocument50 pagesOsci Interimreport 2012 PDFvedrapedraNo ratings yet

- AstronomyAcrossDisciplinesandBorders Mini ReviewDocument31 pagesAstronomyAcrossDisciplinesandBorders Mini ReviewmarcbreglianoNo ratings yet

- François Taddéi - PresentacionDocument36 pagesFrançois Taddéi - PresentacionMikel AgirregabiriaNo ratings yet

- Molek Kozakowska 2018 Making Biosciences Visible For Popular Consumption Approaching Image Text Relations inDocument14 pagesMolek Kozakowska 2018 Making Biosciences Visible For Popular Consumption Approaching Image Text Relations inNeylan Ogutveren AularNo ratings yet

- Master Holzer Ian 2019Document125 pagesMaster Holzer Ian 2019Imoushon WthNo ratings yet

- Toolkit For Museum ReopeningDocument41 pagesToolkit For Museum ReopeningVianca Attoml'No ratings yet

- SubsidenceAnalysisandVisualization IntroDocument13 pagesSubsidenceAnalysisandVisualization IntroJochiephu SihiteNo ratings yet

- Lying in The Gallery : Things Lying Down? Perhaps To Some This Will Sound Like An Academic Nonstarter-ADocument20 pagesLying in The Gallery : Things Lying Down? Perhaps To Some This Will Sound Like An Academic Nonstarter-AhowlongwehavewaitedNo ratings yet

- Dudley Andrew The Core and Flow of Film StudiesDocument40 pagesDudley Andrew The Core and Flow of Film StudiesJordan SchonigNo ratings yet

- Virtual Exploring To Jing-Hang Grand Canal: 18th International Conference On Artificial Reality and Telexistence 2008Document6 pagesVirtual Exploring To Jing-Hang Grand Canal: 18th International Conference On Artificial Reality and Telexistence 2008Carolyn HardyNo ratings yet

- Kirby 2003 Science Consultants Fictional Films and Scientific PracticeDocument38 pagesKirby 2003 Science Consultants Fictional Films and Scientific PracticeFanni BoncziNo ratings yet

- Rough Science GuideDocument24 pagesRough Science GuidevthiseasNo ratings yet

- Journal of Visual Culture 2002 Poster 67 70Document5 pagesJournal of Visual Culture 2002 Poster 67 70Yce FlorinNo ratings yet

- Acta 5Document221 pagesActa 5Bugy BuggyNo ratings yet

- Studies in Documentary Film, Vol.6, Number 2, Interactive Documentary Special 2012Document68 pagesStudies in Documentary Film, Vol.6, Number 2, Interactive Documentary Special 2012Patrícia Nogueira100% (3)