Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Trends and Challenges Toward Integration of Traditional Medicine in Formal Health-Care System: Historical Perspectives and Appraisal of Education Curricula in Sub-Sahara Africa

Uploaded by

AliOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Trends and Challenges Toward Integration of Traditional Medicine in Formal Health-Care System: Historical Perspectives and Appraisal of Education Curricula in Sub-Sahara Africa

Uploaded by

AliCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Intercultural Ethnopharmacology

Mini Review

www.jicep.com

DOI: 10.5455/jice.20160421125217

Trends and challenges toward

integration of traditional medicine in

formal health-care system: Historical

perspectives and appraisal of education

curricula in Sub-Sahara Africa

Ester Innocent

ABSTRACT

Department of Biological The population residing Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA) continues to suffer from communicable health problems such

and Pre-clinical studies, as HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, and various neglected tropical as well as non-communicable diseases. The

Institute of Traditional disease burden is aggravated by shortage of medical personnel and medical supplies such as medical devices

Medicine, Muhimbili and minimal access to essential medicine. For long time, human beings through observation and practical

University of Health and experiences learned to use different plant species that led to the emergence of traditional medicine (TM)

Allied Sciences, P.O. Box systems. The ancient Pharaonic Egyptian TM system is one of the oldest documented forms of TM practice

65001, Dar es Salaam, in Africa and the pioneer of world’s medical science. However, the medical practices diffused very fast to

Tanzania

other continents being accelerated by advancement of technologies while leaving Africa lagging behind in the

Address for correspondence:

integration of the practice in formal health-care system. Challenging issues that drag back integration is the

Ester Innocent, Institute development of education curricula for training TM experts as the way of disseminating the traditional medical

of Traditional Medicine, knowledge and practices imbedded in African culture . The few African countries such as Ghana managed to

Muhimbili University integrate TM products in the National Essential Medicine List while South Africa, Sierra Leone, and Tanzania

of Health and Allied

Sciences, P.O. Box 65001,

have TM products being sold over the counters due to the availability of education training programs facilitated

Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. by research. This paper analyses the contribution of TM practice and products in modern medicine and gives

E-mail: einnocent@muhas. recommendations that Africa should take in the integration process to safeguard the SSA population from

ac.tz disease burdens.

Received: March 02, 2016

Accepted: April 11, 2016 KEY WORDS: Bantu, curricula, formal system, integration, practice, products, Sub-Sahara Africa, traditional

Published: May 04, 2016 medicine

INTRODUCTION TM, Ayurvedic medicine, Naturopathy, Homoeopathy, and

Korean oriental medicine [2-4]. Therefore, the philosophy and

The Contribution of Ancient African Traditional theories of disease symptoms, diagnosis, and treatment used

Medicine (TM) Practices in Modern Medicine in African TM need to be established and learned because the

surge for the use of TM is now not limited to countries of origin

The Sub-Sahara Africa (SSA) continues suffering from the rather a trans-territory and a choice of many people even in

burden of diseases despite being a rich source of biodiversity developed countries [5-8]. African TM practices are imbedded

from which many hospital medicines have been tapped, and a in the indigenous knowledge of one’s culture or society thus

lot more are untapped. This untapped avenue has contributed also serves as backups of what the local communities have

minimally in solving health problems since TM has not yet been maintained for centuries for their survival and prosper within

formally integrated into the existing conventional health-care their ecosystem.

delivery [1]. The reasons being partly because there are few

TM curricula that are geared to trained human resources to In the written record, the ancient Pharaonic Egyptians medical

undertake quality services and development of materia medica practices are the oldest documented form of TM practice in

used in treatments in this region. However, different countries Africa. From the beginning of the civilization in about 3300 BC

or continents elsewhere have their TM practices supported by until the Persian invasion in 525 BC, Egyptian medical practices

documented material medica and the underlying philosophy for were highly advanced for its time including simple non-invasive

disease diagnosis and treatments such as Unani TM, Chinese surgery, bones setting, and an extensive set of pharmacopeia in

J Intercult Ethnopharmacol ● 2016 ● Vol 5 ● Issue 3 1

Innocent: Trends and challenges of integration of TM

the form of papyri. The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1500 BC) is among living or dead (ancestors) and the “intangible forces” (God,

the oldest preserved medical documents and contains some gods,) of the universe [19,20]. Thus, disease is not merely a

700 magical formulas and remedies. Records show that the result of dysfunction of an organ caused by the invasion of

diagnosis of diabetes disease was described in Ebers Papyrus as microscopic organisms (Germ theory) but also may be due to

disease of “urine pass through” [9]. The Edwin Smith papyrus intangible forces. Therefore, treatment in African TM is by

(c. 1600 BC) includes a description of simple non-invasive use of both material substances and resources drawn from the

surgery whereby the position of diagnosis of breast cancer and cosmic world all together not separated (Holistic theory) in

its management is described as a “tumor do thou nothing there an attempts to restore a state of wholesomeness using various

against” [10]. Several other papyri collected in Egypt influenced methods including plant remedies [19,20].

TM of other traditions, including the Greeks and Romans, but

later other parts of the world [11]. Interdependence of Traditional and Modern Medicine

No much is recorded about TM practices in Africa until the The pharaonic pharmacopeia papyri described several plants

19th century when Africa was partitioned and missionaries’ including the bark of the willow tree, in which Hippocrates

works started. For example in by then Germany East Africa (~ 460-370 B.C.) who is acknowledged as a father of western

and British East Africa, which compose the current East Africa medicine used to control headaches and other body pains [21].

Community countries, one British traveller [12] witnessed It was through chemistry, the active molecule which is salicylic

cesarean section being performed by Ugandan people to serve acid was identified, in 1889, and later aspirin, paracetamol,

the baby and mother. Similar reports of surgical practices were diclofenac, mefenamic acid, ibuprofen, etc., were synthesized

reported from Rwanda, whereby botanical preparations were based on the structure of salicylic acid [21,22]. Several other

used to anesthetize the patient to perform a cesarean and useful hospitals medicines and vaccination, such as quinine,

promote wound healing [12]. In Tanzania, the German ship’s ephedrine, amodiaquine, primaquine, chloroquine, mefloquine,

doctor Dr. Weck, Adolf Bastian (1826-1905), W. H. R. Rivers atropine, reserpine, digoxin, tubocurarine, metformin,

(1864-1922), and C. G. Seligman (1873-1940) observed and Scopolamine, taxol, and calanolide A, are now synthetically

wrote a number of diseases being managed by TM in the Hehe made from a structure of an initial naturally isolated compound

community [13,14]. These few examples of ancient indigenous from medicinal plants while others are semi-synthetically derived

practices show the significant contribution to the modern from the natural product precursors [22,23]. Several medicinal

practices of diagnosis and disease management since some plants, such as Madagascar’s rosy periwinkle Catharansus roseus,

still hold to date. remain the basic source of anticancer drugs vincristine and

vinblastine [23]. This indicates the potential of medicinal plants

TM in SSA and its current contribution to hospital medicine, in which

most of these are an essential medicine dispensed worldwide for

In Africa, the Bantu-speaking peoples make up a major part treatment of different diseases. This confirms the contribution

of the population of nearly all African countries south of the of both modern and TM in the advancement of the current

Sahara. They belong to over 300 groups, each with its own health systems not only in SSA but worldwide.

language or dialect [15]. Despite the diverse culture and

ethnic groups in SSA, still, most societies are dominated by Opportunities and Challenges to Promote TM Practices

the Bantu culture and believe [15]. Therefore, TM in the SSA and Products in SSA

region is rational in the context of Bantu cultures and is like

theories in western medicine. The Bantu believes a human The contribution of TM and its practitioners was recognized,

being is holistic yet corporate, in terms of the family, clan in 1978, by the Alma-Ata Declaration as important resources

and whole ethnic group. Therefore, it is required never to in achieving health for all by the year 2000 [24]. A number

do harm to the patient unless it is in his or her best interests of resolutions and declarations have been adopted by the

or for the good of the community because if he suffers, he WHO governing bodies at regional and global levels including

does not suffer alone but with his corporate group: When Resolution AFR/RC49/R5 on Essential Drugs in the WHO

he rejoices, he is not alone but with his kinsmen, neighbors, African Region. The resolution required the WHO to support

and relatives. In the modern health-care system, this is a Member States to carry out research on medicinal plants and

principle worth emulating; never to do harm to a patient to promote their use in health-care delivery systems [25]. The

unless the nurse or doctor, after serious consideration, believes Regional Committee that adopted resolution AFR/RC49/R5

that it is in the interests of the patient or it is necessary also called on the WHO to develop a comprehensive strategy on

for the protection of other patients or the public [16-18]. African TM with the focus on producing evidence [25-27]. Since

The African Union Commission adopted the WHO/Afro then, African countries have been supporting these initiatives

(1976) definition of African TM as the total of all practices, in different ways such as documenting ethnobiomedical

measures, ingredients, and procedures of all kind whether information, scientific evidence/research, media promotion,

material or not which guard against disease/illness to alleviate implementing international and national plans and policies

suffering and cure himself [19]. Thus, African TM does not including the plan of action on the decade of TM for

regard man as a purely physical entity but also takes into (2001-2010) that was extended to cover the period 2010-

consideration the sociological (family or other), whether 2020 [28,29]. Indeed, African Nations are aligning to these

2 J Intercult Ethnopharmacol ● 2016 ● Vol 5 ● Issue 3

Innocent: Trends and challenges of integration of TM

international plans to pull efforts of promoting TM uses alternative and complementary medicine education training

including developing robust policies and legislatives. Further, such as homeopathy as shown in Table 1. Most of the TM

many African countries are signatories to the TRIPs 1994, CBD education programs in public universities are geared at

1998, and Nagoya Protocol 2010, which require governments analyzing the efficacy, safety, and quality of TM products

to put mechanisms for recognition and protection of the vast while the clinical practices were being mostly left to private

available local knowledge and associated used genetic materials sector entities. Notably, several universities and research

including those in TM. This is the commendable direction institutions in SSA countries are running some basic courses

taken in addressing the rights of traditional knowledge holders in phytochemistry, pharmacognosy, natural products chemistry,

whom for centuries have transmitted this knowledge orally and phytomedicine. However, those universities/colleges are

thus continued exposing the region in a risk of biopiracy and not listed as they are out of the scope of the present appraisal.

that some knowledge became forgotten or lost during oral

transmission. The ethnobiomedical information originating DISCUSSION

from African culture could be appropriately coordinated and

disseminated through formal training and research to bring Previously Chitindingu et al., 2014 pointed out the training

about reliability and allow adoption for sustainability of the components in African TM that was offered in South Africa

TM services that benefit the majority of the SSA population. to have a theoretical approach rather than problem-solving

Notably, only a few apprenticeships and formal training can approach [32]. Further, reports indicated difficulties in the

be traced in SSA. initial stages of introducing TM curriculum in biomedical

universities for undergraduates [4,30,32,33]. Nevertheless,

METHODOLOGY the importance of TM in SSA call for setting priorities of

developing medicines from materia medica while streamlining

The current review intends to appraise the trend and situation of TM practices alongside with other health professional training

African TM education training curricula in SSA as one element and services. There only only limited huddles on TM products

in the integration process in the formal health-care system. that are used in treatments as many are crude extracts or are

Analytical methodology used for this appraisal was through in the form of raw materials containing the therapeutic active

internet search from Google, Google Scholar, PubMed, HINARI, ingredients [34]. Some may have been used for centuries by

ISI, Global health training center, and Popline (K4 Health) individuals within their environment in the communities, and

database using the terms or key words: Curriculum or courses, their efficacy and safety is well-known by the entire community

or program in traditional or herbal medicine in Africa alone and and may be acceptable. These can be a good start-up that may

combination. In additional terms such as degree, college, SSA, proceed to be essential medicines to be streamlined in formal

or country names were used in combination with the search health system delivery services if they satisfy the health care

titles. A manual evaluation of searched titles and reference lists needs of the majority of the population and the prescribers

of relevant studies and reviews was also conducted. Furthermore, are made aware of their efficacy and safety. The few African

all articles related to the subject were selected and web-link countries that have managed to integrate TM products in the

or the authors’ affiliation to view the institutional webpage National Essential Medicine List such as Ghana is because

whether they offer any course or training program in TM. Basic it was able to develop curriculum which is used to train TM

courses or program in phytochemistry, pharmacognosy, natural experts as the way of disseminating the indigenous medical

products chemistry, and phytomedicine are not included in this knowledge and practices to several health professionals [35].

appraisal because it is a science of the materia medica without Several African countries such as South Africa, Sierra Leone,

necessarily having a reflection on two key characteristic aspects and Tanzania have TM products being sold over the counters

of TM, that is, practices accompanied with the use of materia facilitated by the research and training programs undertaken

medica. in these countries [30,31,32,36-39].

RESULTS RETRIEVED FUTURE PROSPECTS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

The analytical review of the information related to the Notably, few on-going attempt to integrate TM in formal health

subject on “curriculum or courses, or program in traditional care can be spotted in some SSA countries whereby collaborative

or herbal medicine in Africa” revealed only a few institutions initiatives of some Traditional Health Practitioners Organization

mostly universities or colleges in the countries residing such THETA-Uganda; TAWG-Tanzania; and ZINATHA-

SSA that undertake training in TM or complementary and Zimbabwe work closely with the Ministry of Health in addressing

alternative medicine [Table 1]. Many of the retrievable the prevention and care of HIV/AIDS patients [40,41]. These

information indicated TM training to be tailor-made short attempts are good model toward integration of TM to the

courses geared to develop professional skills for a specific formal system if embraced by formal training of practitioners

community of professionals. Furthermore, noted that, that participate in such collaboration. The training program will

funds for most of the short courses were donor-based thus instill skills and confidence to Traditional Health Practitioners

not sustainable beyond funding period, e.g., the Multi- to work in partnership with modern doctors in the existing

disciplinary University Traditional Health Initiative project formal health system. Other areas that need improvement

of South Africa. Some private owned colleges do conduct in the integration process are modernization of TM to allow

J Intercult Ethnopharmacol ● 2016 ● Vol 5 ● Issue 3 3

Innocent: Trends and challenges of integration of TM

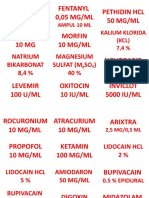

Table 1: Some universities and colleges in Sub-Sahara Africa that offer formal education training in traditional medicine

*Country *Institution Academic program or course offered Citation

Ghana The Kwame Nkrumah University of Bachelor of Science Degree in Herbal https://www.knust.edu.gh/admissions/

Science and Technology, Department Medicine prospective/ugprogrammes

of Herbal Medicine

University of Ghana, Department A Course for Bachelor of Pharmacy http://pharmacy.ug.edu.gh/overview

of Pharmacognosy and Herbal

Medicine

Endpoint homeopathic training Diploma and Degree in Alternative http://www.endpointcollege.com/

institute Medicine

The college of integrated medicine Program in Complementary Health Care at https://www.villagevolunteers.org/village-news/

Certificate Level ghana-college-of-integrated-medicine/

University of Ibadan, College of Training Curricula for Undergraduate http://www.wahooas.org/spip.php?article1017

Medicine

Kenya Kenyatta University, Department Courses for Undergraduate and Graduate http://medicine.ku.ac.ke/

of Pharmacy and Complementary/ Pharmacy index.php/department/

Alternative Medicine pharmacy-and-complementary-medicine

University of Nairobi, Department of Master of Science in Pharmacognosy and http://pharmacology.uonbi.ac.ke//uon_

Pharmacology and Pharmacognosy Complementary Medicines Course degrees_details/733

Sierra Leone University of Sierra Leone, Masters Degree Program in Traditional [30,31]

Department of Pharmacognosy and Medicine

Phytochemistry Pharmacy

Courses in Traditional Medicine For

Pharmacy Medical Undergraduate

South Africa University of KwaZulu-Natal, IKS Research and Postgraduate Training in http://aiks.ukzn.ac.za/about-dst-nrf-ciks

The Department of Science and Traditional Medicine

Technology-National Research

Foundation Centre

University of the Western Cape Postgraduate Programs in Herbal Medicine https://www.uwc.ac.za/Faculties/NS/SAHSMI/

South African, Herbal Science and Tailor-made short courses geared to develop Pages/Programmes.aspx#.UMBzYqyxhP4

Medicine Institute professional skills for a specific health

professionals community, e.g., courses for

Clinical trials in herbal medicine

College of Natural Therapies Postgraduate and Co-graduate Educational http://www.collegeofnaturalhealth.co.za/

Programs

Blackford Centre for Herbal Diploma in Medical Herbalist http://www.studyonline.co.za/herbal/enrol.php

Medicine

Tanzania Muhimbili University of Health Postgraduate (MSc and Ph.D.) Program in http://www.muhas.ac.tz/index.php/academics/

and Allied Sciences Institute of Traditional Medicine Development muhas-institutes/110-itm

Traditional Medicine Module for Undergraduate and Graduate http://itm.muhas.ac.tz/index.php/

Medical Students training-programmes

Department of Veterinary Medicine, Master of Science in Natural Products http://www.suanet.ac.tz/index.php/education/

Sokoine University of Agriculture Technology and value addition programmes-offered-at-sua

*Listed universities/colleges are not exhaustive rather most retrievable list from SSA countries with curricula in traditional medicine. SSA: Sub-Sahara

Africa

easy keeping, dispensing, and transportation in bulk; Clinical REFERENCES

studies of herbal formulas need to be advocated to overcome

the fear of being poisoned; Biodiversity depletion due to use 1. Mendelsohn R, Balick MJ. The value of undiscovered pharmaceuticals

in tropical forests. Econ Bot 1995;49:223-8.

of herbal material from wild source has to be addressed by 2. Payyappallimana U. Role of traditional medicine in primary health

engaging into extensive cultivation while adhering to Good care: An overview of the perspectives and challenges. Yokohama J

Agricultural Practices. It is equally important that traditional Soc Sci 2009;14:69-72.

3. WHO. Benchmarks for Training in Traditional/Complementary and

practices and the philosophy for disease diagnosis and treatment Alternative Medicine: Benchmarks for Training in Traditional Chinese

be disseminated through education curricula, and the relevant Medicine: (WB 55.C4). Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2010.

research should be promoted sustainably. 4. Kim do Y, Park WB, Kang HC, Kim MJ, Park KH, Min BI, et al.

Complementary and alternative medicine in the undergraduate

medical curriculum: A survey of Korean medical schools. J Altern

ACKNOWLEDGMENT Complement Med 2012;18:870-4.

5. Dixon A, Riesberg A, Weinbrenner S, Saka O, Le Grand J, Buse R.

Traditional and Alternative Medicine in the UK and Germany. Research

I thank THETA-Uganda for inviting me to deliver a keynote and Evidence on Supply and Demand. London: Anglo-Germany

presentation during the 3rd Annual National TM Conference Foundation for the Study of Industry Society; 2003.

organized jointly by THETA-Uganda and Uganda National 6. Salomonsen LJ, Skovgaard L, la Cour S, Nyborg L, Launsø L,

Fønnebø V. Use of complementary and alternative medicine at

Health Research Organization (UNHRO), thus stimulated Norwegian and Danish hospitals. BMC Complement Altern Med

compilation of this work. 2011;11:4.

4 J Intercult Ethnopharmacol ● 2016 ● Vol 5 ● Issue 3

Innocent: Trends and challenges of integration of TM

7. Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary 28. WHO. Promoting the Role of Traditional Medicine in Health Systems:

and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. A Strategy for the African Region 2001-2010. Document Reference

Sem Int Med 2004;2:54-71. AFR/RC50/Doc.9/R. Harare: World Health Organization; 2000.

8. Mak JC, Faux S. Complementary and alternative medicine use by 29. Berger M, Murugi J, Buch E, Ijsselmuiden C, Moran M, Guzman J,

osteoporotic patients in Australia (CAMEO-A): A prospective study. et al. Strengthening pharmaceutical innovation in Africa. Council on

J Altern Complement Med 2010;16:579-84. Health Research for Development (COHRED); New Partnership for

9. Zajac J, Shrestha A, Parin P, Poretsky L. The main events in the history Africa’s Development (NEPAD). Gaborone, Botswana: COHRED;

of diabetes mellitus. In: Peretsky L, editor. The Principles of Diabetes 2010. p. 20-3.

Mellitus. New York: Springer; 2010. p. 3-8. 30. James PB, Bah AJ. Awareness, use, attitude and perceived need for

10. Khaled HM. Breast cancer at diagonosis in women of Africa and the complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) education among

Middle East. In: William CK, Olopade OI, Falkson CI, editors. Breast undergraduate pharmacy students in Sierra Leone: A descriptive

Cancer in Women of Africa Decent. Netherland: Springer; 2006. p. cross-sectional survey. BMC Complement Altern Med 2014;14:438.

81-90. 31. Kasilo OM, Trapsida JM, Mwikisa CN, Lusamba-Dikassa PS. An

11. Janzen JM, Green EC. Continuity, change, and challenge in African overview of the traditional medicine situation in the African region.

medicine. In: Selin H, editor. Medicine across Cultures: History and Afr Health Monit 2010;13:7-15.

Practice of Medicine in Non-Western Cultures. Vol. 3. Britain: Kluwer 32. Chitindingu E, George G, Gow J. A review of the integration of

Academic Publisher; 2003. p. 85-114. traditional, complementary and alternative medicine into the

12. Felkin RW. Notes on labour in Central Africa. Edinb Med J curriculum of South African medical schools. BMC Med Educ

1884;29:922-30. 2014;14:40.

13. Bastian A. Weck and the study of traditional Hehe medicine. Tanzania 33. DeJong J. Traditional medicine in Sub-Saharan Africa: Its importance

Notes Rec 1969;70:29-40. and potential policy options. Policy, Research, and External Affairs

14. Bastian A. Weck, Der Wahehe Arzt und seine Wissenschaft, [The Working Papers; No. WPS 735. Population, Health, and Nutrition.

Wahehe Doctor and His Professional Knowledge]. Berlin: Deutsches Washington, DC: World Bank; 1991.

Kolonialblatt; 1908. p. 1048-51. 34. WHO. General Guidelines for Methodologies on Research and

15. Van Lehman D, Eno O. The Somali Bantu Their History and Culture. Evaluation of Traditional Medicine. WHO/EDM/TRM/2000.1. Geneva:

Culture Profile No. 16. Washington, USA: Center for Applied World Health Organization; 2000.

Linguistics; 2003. p. 1-33. 35. Anquandah J. African Ethnomedicine: An Anthropological and Ethno-

16. Onwuanibe RC. The philosophy of African medical practice. J Opin Archaeological Case Study in Ghana. Afr Q Rev Stud Doc Ital Inst Afr

1979;9:25-8. East 1997;52:289-98.

17. Kasenene P. African ethical theory and the four principles. In: Gillon R, 36. Kayombo EJ. Impact of training traditional birth attendants on

editor. Principles of Health Care Ethics. New York: Basic Books; 1994. maternal mortality and morbidity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Tanzan J

Health Res 2013;15:134-42.

p. 183-92.

37. Mahunnah RL, Uiso FC, Kayombo EJ. Documentary of Traditional

18. Mbiti J. African Religions and Philosophy. Oxford: Heinemann; 1969.

Medicine in Tanzania: A Traditional Medicine Resource Book.

p. 101.

Tanzania: Dar-es-Salaam University Press; 2012.

19. WHO. African Traditional Medicine. The AFRO Technical Report

38. Kayombo EJ, Mahunnah RL, Uiso FC. Prospects and challenges of

Series, 1. Report of the Regional Expert Committee, Brazzaville.

medicinal plants conservation and traditional medicine in Tanzania.

1976. p. 3-4.20.

Anthropol 2013;1:3.

20. Okpako DT. In: Nworu CS, Akah PA, editors. Science Interrogating

39. Abdullahi AA. Trends and challenges of traditional medicine in Africa.

Belief: Bridging the Old and New Traditions of Medicine in Africa.

Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med 2011;8 5 Suppl:115-23.

Ibadan, Nigeria: Book Builders; 2015.

40. Kayombo EJ, Uiso FC, Mbwambo ZH, Mahunnah RL, Moshi MJ,

21. Sneader W. Drug Discovery: A History. West Sussex, England: John

Mgonda YH. Experience of initiating collaboration of traditional

Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2005.

healers in managing HIV and AIDS in Tanzania. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed

22. Sneader W. Drug Discovery: The Evolution of Modern Medicines.

2007;3:6.

Chichester, England: Wiley; 1985. 41. Mbwambo ZH, Mahunnah RL Kayombo EJ. Traditional health

23. Newman DJ, Cragg GM. Natural products as sources of new drugs Practitioner and Scientist: Bridging the gap in contemporary research

over the last 25 years. J Nat Prod 2007;70:461-77. in Tanzania. Tanzania Health Bull 2007;9:115-20.

24. WHO. Alma-Ata Primary Health Care. Geneva: World Health

Organization; 1978.

25. WHO. Resolution, AFR/RC28/R3 on the Use of Essential Medicines

and the African Pharmacopoeia. Brazzaville: WHO Regional Office © SAGEYA. This is an open access article licensed under the terms

for Africa; 1978. of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://

26. WHO. Resolution WHA41.19. Traditional Medicine and Medicinal creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/) which permits unrestricted,

noncommercial use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided

Plants. Geneva: World Health Assembly; 1988.

the work is properly cited.

27. WHO. Resolution, AFR/RC49/R5 on Essential Drugs in the WHO

African Region: Situation and Trend Analysis. Final Report of the Source of Support: Nil, Conflict of Interest: None declared.

WHO Regional Committee for Africa. Windhoek Namibia; 1999.

J Intercult Ethnopharmacol ● 2016 ● Vol 5 ● Issue 3 5

You might also like

- WiringDocument244 pagesWiringAli100% (1)

- HILUX Electrical Wiring Diagram GuideDocument244 pagesHILUX Electrical Wiring Diagram Guidethailan100% (2)

- Traditional Medicine in South AfricaDocument8 pagesTraditional Medicine in South AfricaEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- African Medical PluralismFrom EverandAfrican Medical PluralismWilliam C. OlsenNo ratings yet

- X100PRO Key Progamming Vehicle List: Programming KeysDocument135 pagesX100PRO Key Progamming Vehicle List: Programming KeysClaudio CurbeloNo ratings yet

- A Comparative Evaluation of MedicineDocument8 pagesA Comparative Evaluation of MedicineIJMSIR JOURNALNo ratings yet

- Medical Support Manual For UN Field Missions PDFDocument264 pagesMedical Support Manual For UN Field Missions PDFNadia100% (2)

- Fundamentals of Herbal Medicine: History, Phytopharmacology and Phytotherapeutics Vol 1From EverandFundamentals of Herbal Medicine: History, Phytopharmacology and Phytotherapeutics Vol 1No ratings yet

- Traditional African Medicine Is A Range of TraditionalDocument17 pagesTraditional African Medicine Is A Range of TraditionalAlison_VicarNo ratings yet

- TCM Dec 19 IssueDocument15 pagesTCM Dec 19 IssuepranajiNo ratings yet

- 030203en PDFDocument57 pages030203en PDFMichael DavenportNo ratings yet

- Traditional Medicine and Modern Medicine: Review of Related LiteratureDocument4 pagesTraditional Medicine and Modern Medicine: Review of Related LiteratureLen CyNo ratings yet

- The Use of Traditional Medicine in Maternity Care Among African WomenDocument16 pagesThe Use of Traditional Medicine in Maternity Care Among African WomenGabrielAbarcaNo ratings yet

- New Holland tc5070Document3 pagesNew Holland tc5070AliNo ratings yet

- DR - Adi Setia Islamic Medicine ColloquiumDocument11 pagesDR - Adi Setia Islamic Medicine ColloquiumIlham NurNo ratings yet

- BODY CONTROL MODULE CIRCUIT DIAGRAMDocument2 pagesBODY CONTROL MODULE CIRCUIT DIAGRAMAliNo ratings yet

- Computer Data Lines CircuitDocument4 pagesComputer Data Lines CircuitAliNo ratings yet

- Third Quarter Summative Test in Grade 10 Music, Arts, Physical Education & HealthDocument3 pagesThird Quarter Summative Test in Grade 10 Music, Arts, Physical Education & HealthAlbert Ian CasugaNo ratings yet

- Algeria Pharma MarketDocument55 pagesAlgeria Pharma Marketvdved67% (3)

- Antibiotics PDFDocument8 pagesAntibiotics PDFSarah JaneNo ratings yet

- Trends and Challenges of Traditional Medicine in AfricaDocument9 pagesTrends and Challenges of Traditional Medicine in AfricaNancy KawilarangNo ratings yet

- Abdullahi Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. (2011) 8 (S) :115-123Document9 pagesAbdullahi Afr J Tradit Complement Altern Med. (2011) 8 (S) :115-123Desy RatnasariNo ratings yet

- Harnessing The Potential of Indigenous African Plants in HIV Management A Comprehensive Review Integrating Traditional Knowledge With Evidence-Based MedicineDocument11 pagesHarnessing The Potential of Indigenous African Plants in HIV Management A Comprehensive Review Integrating Traditional Knowledge With Evidence-Based MedicineKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- 2-Article Text-119-1-10-20051127Document12 pages2-Article Text-119-1-10-20051127Yusuf riskaNo ratings yet

- Review Article: Traditional Medicines in Africa: An Appraisal of Ten Potent African Medicinal PlantsDocument15 pagesReview Article: Traditional Medicines in Africa: An Appraisal of Ten Potent African Medicinal PlantsCharles ChalimbaNo ratings yet

- Traditional or Modern MedicineDocument2 pagesTraditional or Modern MedicineAsadulla KhanNo ratings yet

- The Role of African Traditional Medical Practices in Adolescent Cognitive Skills Development in Oku Sub Division, North West Region of Cameroon Challenges and ProspectsDocument10 pagesThe Role of African Traditional Medical Practices in Adolescent Cognitive Skills Development in Oku Sub Division, North West Region of Cameroon Challenges and ProspectsEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- ARV Vs HerbalDocument15 pagesARV Vs HerbalDeni Widodo100% (2)

- Importance of Traditional Medicine in AfricaDocument12 pagesImportance of Traditional Medicine in AfricaHenry CommeyNo ratings yet

- Hand Book of Common Ethiopian Traditional MedicinalDocument13 pagesHand Book of Common Ethiopian Traditional MedicinalClaudia RamirezNo ratings yet

- The Sausage Plant (Kigelia Africana) : Have We Finally Discovered A Male Sperm Booster?Document9 pagesThe Sausage Plant (Kigelia Africana) : Have We Finally Discovered A Male Sperm Booster?prabhasNo ratings yet

- IgsDocument3 pagesIgsRoy mugendiNo ratings yet

- 21 53 1 PBDocument15 pages21 53 1 PBLavanya Priya SathyanNo ratings yet

- Prophetic Medicine, Islamic Medicine, Traditional Arabic and Islamic Medicine (TAIM) : Revisiting Concepts and DefinitionsDocument8 pagesProphetic Medicine, Islamic Medicine, Traditional Arabic and Islamic Medicine (TAIM) : Revisiting Concepts and DefinitionsMuhammad MulyadiNo ratings yet

- Muntingia Calabura A Review of Its Traditional Uses Chemical Properties and Pharmacological ObservationsDocument27 pagesMuntingia Calabura A Review of Its Traditional Uses Chemical Properties and Pharmacological ObservationsDharmastuti Fatmarahmi100% (1)

- Traditional Medicine in India: Canadian Family Physician Médecin de Famille Canadien April 1987Document5 pagesTraditional Medicine in India: Canadian Family Physician Médecin de Famille Canadien April 1987Renshi IaskdoNo ratings yet

- Review of Related LiteratureDocument12 pagesReview of Related LiteratureEli EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Pardon T Matyaka BMSDocument8 pagesPardon T Matyaka BMSPardon Tanaka MatyakaNo ratings yet

- IntroductionDocument3 pagesIntroductionSharathrobensonNo ratings yet

- Journal of Ethnobiology and EthnomedicineDocument22 pagesJournal of Ethnobiology and EthnomedicineHrafnaet SorgenNo ratings yet

- Chapter OneDocument6 pagesChapter OneMahmud Rukayya MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Exploring the Cultural and Spiritual Dimensions of EthnomedicineDocument2 pagesExploring the Cultural and Spiritual Dimensions of Ethnomedicineiman14No ratings yet

- ''Traditional Arabic and Islamic Medicine''Document4 pages''Traditional Arabic and Islamic Medicine''tandraini100% (1)

- Addis Ababa Sciece and Technology University Collage of Biological and Chemical Engineering Department of BiotechnologyDocument14 pagesAddis Ababa Sciece and Technology University Collage of Biological and Chemical Engineering Department of BiotechnologyEshetu ShemetNo ratings yet

- Use of Traditional Medicinal Plants by People of Boosat' Sub District, Central Eastern EthiopiaDocument15 pagesUse of Traditional Medicinal Plants by People of Boosat' Sub District, Central Eastern Ethiopiaabdlfet rejatoNo ratings yet

- Future of Traditional MedicineDocument7 pagesFuture of Traditional MedicineEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Rankoana SA 2012 PDFDocument238 pagesRankoana SA 2012 PDFNica DesateNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Management of Traditional Medicine Among People of Burka Jato Kebele, West EthiopiaDocument10 pagesKnowledge, Attitude, Practice, and Management of Traditional Medicine Among People of Burka Jato Kebele, West EthiopiaNibras PinkNo ratings yet

- Medicinal Plants Used To Treat African Diseases by The Local Communities of Bwambara Sub-County in Rukungiri District, Western UgandaDocument12 pagesMedicinal Plants Used To Treat African Diseases by The Local Communities of Bwambara Sub-County in Rukungiri District, Western UgandaHằng NgôNo ratings yet

- Medicine, Mobility, and Power in Global Africa: Transnational Health and HealingFrom EverandMedicine, Mobility, and Power in Global Africa: Transnational Health and HealingNo ratings yet

- Admin,+Journal+Manager,+AJPCR 21893 RADocument6 pagesAdmin,+Journal+Manager,+AJPCR 21893 RAToghrulNo ratings yet

- Wound Care With Traditional, Complementary and Alternative MedicineDocument10 pagesWound Care With Traditional, Complementary and Alternative Medicineyasir aliNo ratings yet

- 33040-O (1) - J. OdeDocument10 pages33040-O (1) - J. OdeAliNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 Review of Related LiteratureDocument12 pagesChapter 2 Review of Related LiteratureCatherine AlcardeNo ratings yet

- 3-Usifoh UdeziDocument9 pages3-Usifoh UdeziNgo NeNo ratings yet

- Developments: in The Field of Medicine and Nursing That Improved Hospital and Health Services in GeneralDocument35 pagesDevelopments: in The Field of Medicine and Nursing That Improved Hospital and Health Services in General202370092No ratings yet

- BUSSMANN Rainer, SHARON Douglas - Traditional Medicinal Plant Use in Northern Peru Tracking Two Thousand Years of Healing Culture - 2006Document18 pagesBUSSMANN Rainer, SHARON Douglas - Traditional Medicinal Plant Use in Northern Peru Tracking Two Thousand Years of Healing Culture - 2006ninkasi1No ratings yet

- 01 Chapter4Document141 pages01 Chapter4Dewi Maspufah100% (2)

- Herbal Medicine Healthcare OverviewDocument6 pagesHerbal Medicine Healthcare OverviewHanny WahyuniNo ratings yet

- AYUSH For Keywords For IndiaDocument6 pagesAYUSH For Keywords For IndiaMadhulika BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- A2Document8 pagesA2alvinNo ratings yet

- Anatomical Sites For Practicing Wet Cupping Therapy Alhijamah 2327 5162.1000138 PDFDocument30 pagesAnatomical Sites For Practicing Wet Cupping Therapy Alhijamah 2327 5162.1000138 PDFsilkofos100% (1)

- Medicinal Plants of The Subanens in Dumingag, Zamboanga Del Sur, PhilippinesDocument6 pagesMedicinal Plants of The Subanens in Dumingag, Zamboanga Del Sur, PhilippinesElijah AlamilloNo ratings yet

- Important Medicinal Plants of Ethiopia: Uses, Knowledge Transfer and Conservation PracticesDocument12 pagesImportant Medicinal Plants of Ethiopia: Uses, Knowledge Transfer and Conservation Practicesdereje yiemeruNo ratings yet

- Efood - 2020 - Sieniawska - Plant Based Food Products For Antimycobacterial TherapyDocument18 pagesEfood - 2020 - Sieniawska - Plant Based Food Products For Antimycobacterial TherapyRavi P ShaliwalNo ratings yet

- African Traditional Medicine's Contributions to Nigeria's HealthcareDocument12 pagesAfrican Traditional Medicine's Contributions to Nigeria's HealthcareAliNo ratings yet

- Art 02Document4 pagesArt 02Aparajita BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- Overview of Medicine - Its Importance and ImpactDocument9 pagesOverview of Medicine - Its Importance and ImpactDuffosNo ratings yet

- Daphne Plants Review Biological and Pharmacological ActivityDocument12 pagesDaphne Plants Review Biological and Pharmacological ActivityKrisman Umbu HengguNo ratings yet

- Engine 1 Ford f150Document869 pagesEngine 1 Ford f150AliNo ratings yet

- 011-1 Fuse and Relay InformationDocument20 pages011-1 Fuse and Relay InformationKendall BrownNo ratings yet

- Evoque 2011-13 - Fuel Charging and Controls - Turbocharger - TD4 2.2L DieselDocument16 pagesEvoque 2011-13 - Fuel Charging and Controls - Turbocharger - TD4 2.2L DieselAliNo ratings yet

- 418-00-Module Communications Network 418-00Document128 pages418-00-Module Communications Network 418-00mail4281No ratings yet

- Evoque 2011-13 - Engine Emission Control - TD4 2.2L DieselDocument32 pagesEvoque 2011-13 - Engine Emission Control - TD4 2.2L DieselAliNo ratings yet

- Ewd 6Document6 pagesEwd 6AliNo ratings yet

- Alinhamento de RodaDocument240 pagesAlinhamento de RodaCleyton C RibeiroNo ratings yet

- Evoque 2011-13 - Engine Ignition - GTDi 2.0L PetrolDocument9 pagesEvoque 2011-13 - Engine Ignition - GTDi 2.0L PetrolAliNo ratings yet

- 6.4L, Engine Performance CircuitDocument6 pages6.4L, Engine Performance CircuitAliNo ratings yet

- 2016 Grand Cherokee - 3.0L TURBO DIESEL PDFDocument665 pages2016 Grand Cherokee - 3.0L TURBO DIESEL PDFprueba2No ratings yet

- Exhaust System GuideDocument6 pagesExhaust System GuideMaiChiVuNo ratings yet

- 2014+ Jeep Trailhawk EWD - Automatic AC CircuitDocument10 pages2014+ Jeep Trailhawk EWD - Automatic AC Circuitcarlos cNo ratings yet

- 2014+ Cherokee WK2 EWD - Electronic Air Suspension CircuitDocument2 pages2014+ Cherokee WK2 EWD - Electronic Air Suspension CircuitAliNo ratings yet

- SM 7Document202 pagesSM 7Muhammed DoumaNo ratings yet

- Aautomatic Transmission CircuitDocument1 pageAautomatic Transmission CircuitAliNo ratings yet

- Body Repair: SectionDocument60 pagesBody Repair: SectionMax SamNo ratings yet

- Engine Cooling System: SectionDocument23 pagesEngine Cooling System: SectionMaiChiVuNo ratings yet

- New Holland tc5070Document2 pagesNew Holland tc5070AliNo ratings yet

- Instrumentation 2 0 Issue 5Document97 pagesInstrumentation 2 0 Issue 5CarlosNo ratings yet

- Fuel System - Juke 2014 - Get FreeDocument31 pagesFuel System - Juke 2014 - Get FreeAliNo ratings yet

- Charging System: SectionDocument29 pagesCharging System: SectionMax SamNo ratings yet

- Opm 0000460 01 PDFDocument60 pagesOpm 0000460 01 PDFUserfabian215No ratings yet

- TP LinkDocument10 pagesTP LinkAliNo ratings yet

- Regional Strategic Framework On Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) in The South-East Asia Region 2012-2017Document40 pagesRegional Strategic Framework On Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) in The South-East Asia Region 2012-2017Himel RakshitNo ratings yet

- Formularium 2018Document9 pagesFormularium 2018novidyahNo ratings yet

- Bartlett, Hugh H. - Madness, Medicine, and Witchcraft in Bududa, Uganda (2017)Document39 pagesBartlett, Hugh H. - Madness, Medicine, and Witchcraft in Bududa, Uganda (2017)Pedro SoaresNo ratings yet

- Senthil Vaccination Certificate - R1740702Document1 pageSenthil Vaccination Certificate - R1740702Abhijith RajuNo ratings yet

- Lista Medicamente CNASDocument162 pagesLista Medicamente CNASMirela MitroiNo ratings yet

- Family Escapes Death: Ti Gonzi Quits Drugs: Robbed During DemolitionsDocument16 pagesFamily Escapes Death: Ti Gonzi Quits Drugs: Robbed During DemolitionsAndrew JoriNo ratings yet

- ΔΤΦ 06082013Document1,140 pagesΔΤΦ 06082013LOUI_GRNo ratings yet

- Drug Price TNMSCDocument13 pagesDrug Price TNMSCdrtpkNo ratings yet

- Mutifa 01.10.22Document3 pagesMutifa 01.10.22Apotek Mirza Praktek Dokter UmumNo ratings yet

- Compatibility chart for syringes within 15 minutesDocument1 pageCompatibility chart for syringes within 15 minutesNadia BadacăNo ratings yet

- 13 Social and Cultural Factors Related To Health Part A Recognizing The Impact PDFDocument94 pages13 Social and Cultural Factors Related To Health Part A Recognizing The Impact PDFMarwaKhairatNo ratings yet

- PT.BINTANG SEMESTA FARMA SEMARANG MEDICATION LISTDocument13 pagesPT.BINTANG SEMESTA FARMA SEMARANG MEDICATION LISTAiko Cheryl SalsabilaNo ratings yet

- WHO Modern Disease Into AyurvedaDocument608 pagesWHO Modern Disease Into Ayurvedatom_curitibaNo ratings yet

- Algorithm 1 Algorithm 2Document51 pagesAlgorithm 1 Algorithm 2Zimm RrrrNo ratings yet

- ICEP CSS - PMS Dawn+ 24 June, 2020 by M.Usman and Rabia Kalhoro PDFDocument24 pagesICEP CSS - PMS Dawn+ 24 June, 2020 by M.Usman and Rabia Kalhoro PDFBiYa ɱɥğȟålNo ratings yet

- Tablet Sept'12 - Aprl 2015 - VeraDocument120 pagesTablet Sept'12 - Aprl 2015 - VeraisyeabdullahNo ratings yet

- Preventing and Managing COVID-19 Across Long-Term Care ServicesDocument8 pagesPreventing and Managing COVID-19 Across Long-Term Care ServicesMark Anthony MadridanoNo ratings yet

- Label ObatDocument31 pagesLabel ObatAndiTenriBayangNo ratings yet

- Ecart DrugsDocument1 pageEcart DrugsKarla JaneNo ratings yet

- Lap Bulanan JKNDocument42 pagesLap Bulanan JKNIsti YulistinaNo ratings yet

- Fornas SaptosariDocument42 pagesFornas SaptosariRisnantoNo ratings yet

- Data Pasien Asma Excel Rev 2Document5 pagesData Pasien Asma Excel Rev 2Rio OsnandaNo ratings yet

- 2022 CHAI HIV Market Report 12.8.22Document45 pages2022 CHAI HIV Market Report 12.8.22Rakesh KumarNo ratings yet

- The WHO Health Promotion Glossary PDFDocument17 pagesThe WHO Health Promotion Glossary PDFfirda FibrilaNo ratings yet

- Daftar Obat High Alert Dan LasaDocument1 pageDaftar Obat High Alert Dan LasaDwinda Juli sandaniNo ratings yet

- Price List Cv. Untung Kumoro: End of ReportDocument144 pagesPrice List Cv. Untung Kumoro: End of ReportdedirahadiNo ratings yet