Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Occupational & Environmen-1

Uploaded by

Baihaqi Saharun0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views3 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

9 views3 pagesOccupational & Environmen-1

Uploaded by

Baihaqi SaharunCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 3

3 April 2015

Occupational &

Environmental Medicine

Passive exposure to bleach at home linked to higher

childhood infection rate

Effects modest, but widespread use of bleach adds up to public

health concern, say researchers

Passive exposure to bleach in the home is linked to

higher rates of childhood respiratory and other infections,

suggests research published online in Occupational &

Environmental Medicine.

Although modest, the results are of public health concern in

light of the widespread use of bleach in the home, say the

researchers, who call for further more detailed studies in this

area.

The researchers looked at the potential impact of exposure to

bleach in the home among more than 9000 children between

the ages of 6 and 12 attending 19 schools in Utrecht, The

Netherlands; 17 schools in Eastern and Central Finland; and 18

schools in Barcelona, Spain.

Their parents were asked to complete a questionnaire on the

number and frequency of flu; tonsillitis; sinusitis; bronchitis;

otitis; and pneumonia infections their children had had in the

preceding 12 months. And they were asked if they used bleach

to clean their homes at least once a week.

Use of bleach was common in Spain (72% of respondents) and

rare (7%) in Finland. And all Spanish schools were cleaned with

bleach, while Finnish schools were not.

After taking account of influential factors, such as passive

smoking at home, parental education, the presence of

household mould, and use of bleach to clean school premises,

the findings indicated that the number and frequency of

infections were higher among children whose parents regularly

used bleach to clean the home in all three countries.

These differences were statistically significant for flu, tonsillitis,

and any infection.

The risk of one episode of flu in the previous year was 20%

higher, and recurrent tonsillitis 35% higher, among children

whose parents used bleach to clean the home.

Similarly, the risk of any recurrent infection was 18% higher

among children whose parents regularly used cleaning bleach.

This is an observational study, so no definitive conclusions can

be drawn about cause and effect. Furthermore, the authors

highlight several caveats to their research.

For example, they didn’t have any information on the use of

other cleaning products used in the home, and only basic

information was gathered on the use of bleach in the home,

making it difficult to differentiate between exposure levels.

But their findings back other studies indicating a link between

cleaning products and respiratory symptoms and inflammation,

they say.

And they add: “The high frequency of use of disinfecting

cleaning products, caused by the erroneous belief, reinforced

by advertising, that our homes should be free of microbes,

makes the modest effects reported in our study of public health

concern.”

By way of an explanation for the associations they found, they

suggest that the irritant properties of volatile or airborne

compounds generated during the cleaning process may

damage the lining of lung cells, sparking inflammation and

making it easier for infections to take hold. Bleach may also

potentially suppress the immune system, they say.

###

Research: Trends in 30-day mortality rate and case mix for

paediatric cardiac surgery in the UK between 2000 and 2010

www.oem.bmj.com/lookup/doi/10.1136/oemed-2014-102701

You might also like

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Somatoform Disorders: NUR 444 FALL 2015Document37 pagesSomatoform Disorders: NUR 444 FALL 2015Amit TamboliNo ratings yet

- Additive EfectDocument8 pagesAdditive EfectMAIN FIRSTFLOORBNo ratings yet

- Jurnal CapDocument3 pagesJurnal CapNurfhalisa Dwi Putri MRNo ratings yet

- Anclynostoma Duodenale Ancylostoma Duodenale Ancylostoma Ancylostoma Duodenale Necator Americanus Ancylostoma DuodenaleDocument3 pagesAnclynostoma Duodenale Ancylostoma Duodenale Ancylostoma Ancylostoma Duodenale Necator Americanus Ancylostoma DuodenaleMarwin OditaNo ratings yet

- Asuhan Keperawatan Pada Klien Dengan Proses Penyembuhan Luka. Pengkajian Diagnosa Perencanaan Implementasi EvaluasiDocument43 pagesAsuhan Keperawatan Pada Klien Dengan Proses Penyembuhan Luka. Pengkajian Diagnosa Perencanaan Implementasi EvaluasiCak FirmanNo ratings yet

- 1 Litre of TearsDocument1 page1 Litre of TearsSamantha DeangkinayNo ratings yet

- Standard 15 CC Workbook PDFDocument17 pagesStandard 15 CC Workbook PDFbinchacNo ratings yet

- Homoeopathic Treatment of Typhoid Fever: A Case Report: January 2022 8 (2) :2-7Document6 pagesHomoeopathic Treatment of Typhoid Fever: A Case Report: January 2022 8 (2) :2-7Aishwarya JoshiNo ratings yet

- Herpes Zoster Ophthalmicus Review and Prevention: Andrew R. Davis, and John SheppardDocument6 pagesHerpes Zoster Ophthalmicus Review and Prevention: Andrew R. Davis, and John SheppardVincentius Michael WilliantoNo ratings yet

- Doctor (A2) : Did You Understand The Text?Document2 pagesDoctor (A2) : Did You Understand The Text?Hachani SoumayaNo ratings yet

- J of Cosmetic Dermatology - 2023 - Aryanian - Various Aspects of The Relationship Between Vitiligo and The COVID 19Document5 pagesJ of Cosmetic Dermatology - 2023 - Aryanian - Various Aspects of The Relationship Between Vitiligo and The COVID 19AinaaqorryNo ratings yet

- Zoonotic DiseasesDocument27 pagesZoonotic DiseasesGift Summer DinoNo ratings yet

- Candida AurisDocument5 pagesCandida AurisSMIBA MedicinaNo ratings yet

- Bleeding Disorders: Dairion Gatot, Soegiarto Gani, Savita HandayaniDocument50 pagesBleeding Disorders: Dairion Gatot, Soegiarto Gani, Savita HandayaniririsNo ratings yet

- Malnutrition TableDocument1 pageMalnutrition TableTeddy Kurniady ThaherNo ratings yet

- Psychosis in WomenDocument7 pagesPsychosis in WomenMarius PaţaNo ratings yet

- MS Soapie #1Document2 pagesMS Soapie #1Fatima KateNo ratings yet

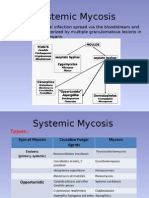

- MycosisDocument5 pagesMycosisMaiWahidGaberNo ratings yet

- Health Care in Global 2018 PDFDocument36 pagesHealth Care in Global 2018 PDFTony Miguel Saba SabaNo ratings yet

- 609-Article Text-1082-2-10-20190708Document10 pages609-Article Text-1082-2-10-20190708Nova RizkenNo ratings yet

- Dietabajaencarbohidratos Moreno Capponi 2020Document11 pagesDietabajaencarbohidratos Moreno Capponi 2020PerlaNo ratings yet

- Hypertension: Management and TreatmentDocument9 pagesHypertension: Management and TreatmentSheila May Teope SantosNo ratings yet

- NorovirusDocument9 pagesNorovirusCaroline AdhiamboNo ratings yet

- Latin English DictDocument35 pagesLatin English DictUruk SumerNo ratings yet

- Prometric ExamDocument8 pagesPrometric Exammsathu76No ratings yet

- C Reactive ProteinDocument24 pagesC Reactive ProteinMohammed FareedNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology For Business - Healthy LifestyleDocument9 pagesResearch Methodology For Business - Healthy LifestyleRameshwar FundipalleNo ratings yet

- (Eter Baldwin-Disease and Democracy - The Industrialized World Faces AIDS-University of California Press (2005)Document479 pages(Eter Baldwin-Disease and Democracy - The Industrialized World Faces AIDS-University of California Press (2005)Emilija DanilaitytėNo ratings yet

- 2017 Residancy Exam JUHDocument8 pages2017 Residancy Exam JUHMohammadSAL-RawashdehNo ratings yet

- MMR Vaccine: Review of Benefits and RisksDocument6 pagesMMR Vaccine: Review of Benefits and RisksAldo Pravando JulianNo ratings yet