Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Strategic Orientation

Uploaded by

Rodrigo BressanCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Strategic Orientation

Uploaded by

Rodrigo BressanCopyright:

Available Formats

Similarities and Differences in the Strategic Orientation, Innovation

Patterns and Performance of SMEs and Large Companies

Dr. Kamalesh Kumar, University of Michigan-Dearborn, Dearborn, MI

ABSTRACT

This study examined the similarities and differences in the strategic orientation and innovation patterns of

SMEs and large companies and investigated their implications for company performance. Data collected over a two

year period was analyzed to determine the strategic orientations of SMEs and large firms, in terms of the Miles and

Snow typology. Results showed that while large firms operated with a “prospector” orientation, the vast majority of

SMEs possessed a “defender” or “reactor” orientation. Results also showed that, while in general, SMEs had taken a

defensive posture, introducing products that involve low novelty of innovation, a small number of SMEs were able

to innovate successfully in all product categories. An ex post facto investigation revealed that these firms had, in

effect followed an "open innovation model" (Chesbrough, 2003) that involve the use of external actors and sources

to help them achieve and sustain innovation. Implications of the finding for SME's competitive strategy and future

research are discussed.

INTRODUCTION

A survey of the strategy literature provides rather unequivocal evidence that a company’s strategic

orientation plays a major role in its innovativeness and that innovation is a key driver of competitiveness and

company performance. But there appears to be a relative lack of research that has examined the similarities and

differences in the strategic orientation, innovation pattern and performance of small (companies with less than 250

employees) and medium (companies with less than 500 employees) enterprises (SMEs) and large companies within

a single industry (Laforet, 2008; O’Regan and Ghobadian, 2005). Differences in the strategic orientation and

innovativeness of the SMEs and large companies become particularly relevant, when these companies are operating

in a dynamic market because the capability to adapt to changes in market can have a major effect on the profitability

and even survival of companies.

Purpose of the present study

The purpose of the present study is to examine the similarities and differences in the strategic orientation

and innovation patterns of SMEs and large companies within the same industry and to investigate their implications

for company performance. Given the problem of balancing the benefits and costs of adaptability, and the fact that

SMEs are known to approach changes in the industry environment in a tactical rather than strategic way (Laforet,

2008) it is possible that at one extreme, some SMEs may create a strategic orientation aimed at adapting to market

changes, but at a significant cost, while others may focus internally on a narrowly defined product-market, but with

the accompanying risk of failure to adapt to market changes, and the prospect of declining sales and profitability.

The findings of this study will make contributions to both theory and practice. From a theoretical

perspective, findings of this study should fill in a gap that currently exists in the literature by understanding the

similarities and differences in the strategic orientation, innovation pattern and performance of SMEs and large

companies in a dynamic industry environment. Results of this study will also provide some insight to managers of

new food product development, concerned about low rate of innovation and high rate of failure of new food

products (Boesso, Davcik and Favotto, 2009).

INDUSTRY AND COUNTRY SETTING FOR THIS STUDY

This study is based upon sales data collected every two weeks over a two year period, relating to yogurt

products introduced in the past five years in Italy. Recent product innovations in the Italian yogurt market is

characterized by increased emphasis on the health benefits of the product and introduction of new kinds of yogurts

that offer health benefits that reach beyond basic nutrition. Nearly all the competing companies have come up with

products that involve various levels of novelty. It is common in studies of innovation to examine the differences in

innovations based upon the degree of novelty. Also, a variety of empirical studies have shown that the level of

novelty of an innovation strongly influences the company performance (Garcia and Calatone, 2002). Determining

the level of novelty associated with new product introductions in yogurt is particularly important given this study’s

The Business Review, Cambridge * Vol. 16 * Num. 2 * December * 2010 50

focus on determining company’s strategic orientation and the relationship between innovation patterns and company

performance.

Following the guidelines provided by AcNielsen and other industry experts, the yogurt products introduced

during the past five years in the Italian market was classified into for distinguishable categories (AcNielsen, 2005).

In the first group are the “Natural Wellness” products that focus on reduced harmful ingredients (such as fat or

sodium) and/or highlight healthful components (such as vitamins and minerals). Most of the products offered in this

category largely involve redevelopment of old products to create new products, together with better labeling and

highlighting of the health benefits. In the second category are products labeled as “Organic”. These products claim

not to contain certain kinds of ingredients (such as growth hormones, antibiotics, genetically modified products etc),

and thus meet the organic product standards. Once again the level of innovation novelty associated with such

products is rather low. Products classified as “Natural Functional” (the third category) are enhanced or fortified with

added supplements such as vitamins or acidophilus cultures/probiotics and claim to promote health benefits. These

products are based on general research and knowledge and involve reformulation of existing ingredients and

manufacturing processes. Finally, products in the “Clinical Functional” category make claims based upon active

ingredients over which the company may have proprietary rights and the benefits of these ingredients have been

tested either in the company’s own laboratories or by external research institutions in independent clinical studies.

These products represent some of the most significant innovations that have occurred in the yogurt industry in the

recent years.

STRATEGIC ORIENTATION, INNOVATION AND PERFORMANCE

Strategic orientation refers to a pattern of responses that an organization makes as it responds to its

operating environment to achieve enhanced performance and competitive advantage (Hambrick, 1983). The Miles

and Snow typology focuses on the “dynamic process of adjusting to environmental change and uncertainty” (Miles

and Snow, 1978, p. 3), and effectively takes into consideration the tradeoff between external and internal factors

(Mckee et al., 1989). Since this study proposes to examine the differences in the innovation patterns of SMEs and

large companies based on data related to sales of newly introduced products, therefore, using the Miles and Snow

(1978) classification typology appears to be the most suitable framework. According to Miles and Snow (1978)

typology, “prospectors” are organizations with strong concern for product and market innovation; they maximize

new opportunities and pioneer innovations to meet market needs. “Defenders”, by contrast, have narrow product-

market domain, conduct little new product development, avoid unnecessary risks and focus on efficiency of existing

operations. “Analyzers” are hybrid of prospector and defender types. They use efficiency in stable product market

segment and innovate in dynamic product markets. Finally, “reactors” are not a stable strategy type, since they are

not able to respond effectively to environment, making adaptations only when forced to do so by the environmental

pressures.

Strategic Orientation and Innovation Patterns: SMEs vs. Large Companies

It has been noted that innovation is one of the key ways by which companies can adapt to and manage their

environments (Cohen and Cyert, 1973). However, all firms, in the same industry or even the same industry

segment, are known not to respond to the environmental changes in the same way (Garcia-Pont and Nohria, 2002).

One may find that some firms anchor their reactions to the changes in the environment primarily to the behaviors of

other firms who are strategically similar to them, while others may adopt a more independent stance, such as a

strong emphasis on new product or market innovation. Since SMEs have their own unique needs, and since their

decision making processes often differ significantly from those of larger firms (Shrader et al., 1989), this would

imply that SMEs and large firms will address the opportunities and threats perceived in the industry environment in

their own unique ways. Therefore, it is only logical to conclude that the strategic orientation of SMEs, as

determined by the way in which they change their products and markets, will differ from those of larger firms in the

same industry.

Based on available information regarding the general attitude of Italian SMEs towards R&D and innovation

one could reasonably anticipate their response patterns to the environmental change. Data provided by OECD

(2005) shows that Italian SMEs spend 1.1% of the GDP on R & D versus the European average of 1.8 percent and

OECD average of 2.3 percent. Given the propensity for low investment aimed at innovation, one would expect that

the vast majority of the Italian SMEs may tend to focus on a narrowly defined product market, creating a defender

orientation, while some in the minority may aim their innovation in terms of balancing the benefits and costs

associated with innovation efforts that help them better adapt to the environment, giving them analyzer orientation.

The Business Review, Cambridge * Vol. 16 * Num. 2 * December * 2010 51

On the other hand, research shows that larger organizations generally tend to have greater slack—“cushion of actual

or potential resources which allows…to initiate changes in strategy with respect to the external environment”

(Burgeois, 1980, p. 30). One would expect such organizations to make greater efforts aimed at adapting to market

changes, giving them a prospector orientation. Accordingly, it is hypothesized that:

H1 (a) More large firms will show a prospector orientation than SMEs.

H1 (b) More SMEs will show a defender and an analyzer orientation than large firms.

H1 (c) Reactor orientation will be limited to SMEs.

Innovation Orientation and Performance

Miles and Snow (1978) had initially suggested that none of their three stable strategy types (prospector,

defender and analyzer) would inherently exhibit superior performance. However, Hambrick (1983) found

differences in the performance of organizations classified as different innovation types. More recent research has

also shown a link between an organization’s strategic orientation, innovation capability and performance (Hughes

and Morgan, 2008). These findings would suggest that differences in the strategic orientations of SME and large

firms will also result in differences between the performance of SMEs and large firms. Since the earlier hypotheses

had predicted that more large firms will show a “prospector” orientation than SMEs, it appears logical to conclude

that large firms will have higher sales volume and will be able to command higher prices than SMEs in product

categories that involve considerable novelty of innovation. This is because the “prospector” organizations are able to

innovate better, devote more resources to products that meet the market needs and spend more on marketing related

activities (McDaniel and Kolari, 1987; O’Regan and Ghobadian, 2005) relative to other strategy types.

H2 (a): Large companies will have higher sales volume in the product categories that involve higher novelty of

innovation (“Clinical Functional” and “Natural Functional” products) than SMEs.

H2 (b): Large companies will be able to command higher prices in the product categories that involve higher

novelty of innovation (“Clinical Functional” and “Natural Functional” products) than SMEs.

Hypotheses 1 had predicted that more SMEs will show a defender and an analyzer orientation than large

firms and that reactor orientation will be limited to SMEs. While firms with a “defenders”, orientation will have a

narrow product market scope, a lower level of cost and therefore, a greater ability to compete aggressively in their

focused product category, firms with an analyzer orientation will offer more products across various product

categories, involving both high and low novelty of innovation. As such, in terms of overall performance comparison

between large firms and SMEs, one would expect that the competitive advantage of SMEs will be largely limited to

the product categories that involve lower novelty of innovation.

H2 (c): SMEs will have higher sales volume and sales revenue in product categories that involve lower novelty of innovations

(Natural Wellness and Organic products) than large firms.

Finally, one could argue that differences in strategic orientation and innovativeness of SMEs and large

companies are related to company type. As noted earlier, building strategic adaptability requires financial resources

and organizational support mechanisms-both of which are known to be relatively lacking among SMEs (O'Regan

and Ghobadian, 2005). Thus even while SMEs may be aware of the need for strategic adaptation and innovation,

they may suffer from the "liability of smallness", which would preclude their presence from product segments that

command higher price, thus making them settle for lower profitability (Laforet, 2008). Large companies on the

other hand devote more resources to products that meet the market needs and spend more on marketing related

activities. It is, therefore, hypothesized that:

H3: Company type (SMEs vs. large company) will be related to the overall pricing ability of a firm.

METHODOLOGY

Database

The data for this study consisted of 592 yogurt products that were introduced into the Italian market during

the past five years by the entire population of 62 companies that sell yogurt in Italy. Data was sourced from

AcNielsen, Italy, using their proprietary Consumer Panel Solutions and Homescan © research tool. The data set

included 107,000 actual yogurt purchases made by 10,282 Italian families, during a two year period from July 2005

to June 2007. According to AcNielsen, Homescan © consumer panel, “has emerged as the premiere consumer

The Business Review, Cambridge * Vol. 16 * Num. 2 * December * 2010 52

purchasing panel in the world, providing key insights in 27 countries, based on consumer purchase information from

over 260,000 households globally. The AcNielsen Homescan © panel of Italian families used for collecting data that

was used in this study involved sampling techniques that makes the consumer panel representative of the general

Italian household population.

Data Analysis

Data analysis for this study was conducted in three phases. Phase one involved the use of cluster analysis,

with the derived clusters serving as the basis for strategic orientation of the firms. The SPSS two-step cluster

analysis program was used to generate the clusters. This program uses an agglomerative hierarchical clustering

method and is capable of handling both categorical and continuous variables. The second phase of the data analysis

examined differences between SMEs and large companies in terms of type of product innovation, sales volume,

sales revenue, and product pricing. Finally, to test the relationships between company type (SMEs vs. large

companies), types of product innovation and company performance (as measured pricing ability), an OLS regression

was run, where price charged across all product categories was the dependent variable; company type and types of

product innovation were independent variables; and quantity purchased and promotional offers made by companies

were control variables. Controlling for the quantity purchased and promotional offers made by companies was

important, as they can influence the quantity purchased and price paid for the products.

Price Charged= C + β1 Type of Product Innovation+ β2 Company Type + β3 Quantity purchased + β4 Promotion + ε

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Table 1 presents the result of the cluster analysis for the 62 companies that formed the entire population of

companies that sell yogurt products in Italy. The analysis shows that 8 companies (13% of the total population)

have a “prospector” orientation, 9 companies (15%) follow an “analyzer” orientation, 28 (45%) of the companies

possess a “defender” orientation and finally, 17 companies (27%) were noted to operate with a “reactor” orientation.

In terms of company type, all of the large companies possessed a “prospector” orientation, while among the SMEs 9

possessed an “analyzer” orientation, 28 a “defender” orientation and 17 a “reactor” orientation.

These results provide strong support for hypotheses 1 (a) which had predicted that more large firms will

possess a “prospector” orientation than SMEs, and for hypotheses 1 (b) which had predicted that more SMEs will

show a defender and analyzer orientations than large firms. Results of cluster analysis also show that the reactor

orientation is limited to SMEs, as predicted by hypothesis 1 (c). The characteristics associated with the four clusters

derived in this study appeared to closely follow the characteristics described in the Miles and Snow typology (1978).

Firms with a “prospector” orientation clearly appeared to pioneer innovations to meet market needs as evidenced by

their offering of 112 products in the “Clinical Functional” product category vs. 31 and 5 product offerings by

companies with “analyzer” and “defender” orientations. The average price charged for products, sales volume and

sales revenue of firms in this strategic group also showed that these firms were able to maximize opportunities

associated with this new product category.

True to the typology, companies with an “analyzer” orientation offered products across the board, with a

significant number of products in categories that involve considerable novelty of innovation (“Clinical Functional”

and "Natural Functional" products) while maintaining a strong presence in other product categories. Firms with a

“defender” orientation appeared to have a narrow product domain, concentrating on “Organic” and “Natural

Functional” product categories. Finally, “reactor” firms offered the least number of products, almost all of which

involved low novelty of innovation. The fact that they were unable to respond effectively to new market

opportunities was evidenced by the relative dearth of products in categories that involve high novelty of innovations.

A review of their sales pattern across various product categories revealed that these firms largely offered products

that may be viewed as commodities by consumers. Although these companies may be able to survive as long as the

market for these product segments is large enough to support multiple players, but the slow growth rate and lower

price of products in this category raises doubts about their long-term viability.

Performance comparison of SMEs and large companies in terms of average sales volume, sales revenue,

and price charged for products in each product category is provided in Table 2. Results presented in this table test

hypotheses 2 (a) through 2 (c). Results show that large firms dominate the “clinical functional” product category in

terms of sales (408.54 vs. 138.75 for SMEs), sales revenue (€ 3,419.8 vs. €756.99 for SMEs) and pricing ability (€

5.68 vs. €5.08 for SMEs). However, SMEs appear to be have a similar dominance in the “natural functional”

The Business Review, Cambridge * Vol. 16 * Num. 2 * December * 2010 53

product categories, which is next in terms of innovation novelty. SMEs account for nearly ninety percent of the

average sales volume (42.96 vs. 4.35 for large firms) and sales revenue (€ 179.11 vs. €15.87 for large firms). SMEs

are also able to command a much higher price (€4.69 vs. € 3.63). When viewed together with the cluster analysis

results presented in Table 1, one can see that this product segment is dominated by SMEs with a defender

orientation. These results provide only partial support for hypotheses 2 (a) and 2 (b). It appears that while large

firms dominate the product category that involves the highest level of innovation novelty, the SMEs, dominate the

product category that follows next in terms of novelty of innovation. It is, however, worth noting that the “clinical

functional” product category is over twelve times larger (€290,544 vs. €22,749) than the natural functional product

category, providing the large companies with a commanding dominance of the market. Notwithstanding the

reasons, only a small number of SMEs had successfully capitalized on this growth opportunity.

Table 3 presents the results of the OLS regression designed to test hypothesis 3 which had predicted that

company type will be related to overall pricing ability of the firm. Results of the regression analysis show that the

ability to charge higher price is only influenced by the type of product innovation (coefficient .34, sig <.01).

Therefore, no support is found for hypothesis 3. This implies that the overall pricing ability is only determined by

the type of product innovation regardless of the company type. This unexpected finding may have important

implications for the SMEs ability to compete against large firms.

CONCLUSIONS AND MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS

Every organization, SMEs and large firms alike, has its perceived view of the operating environment, and

the strategic orientation adopted by the firm follows from this view. The strategic orientation, in turn, determines

the firm’s response to changes in the industry environment, and becomes a primary driver of the extent and kinds of

innovation efforts made by the organization. Results of this study show that the vast majority of SMEs have taken a

defensive posture in view of the industry changes. Based on the above results the overall conclusion regarding the

SMEs ability to compete against the large firms is rather obvious: SMEs suffer from important competitive

disadvantage in the product category that involved highest novelty of innovation and have highest growth and profit

potential. Interestingly however, SMEs appear to enjoy a clear competitive advantage in the product category that

follows next in terms of novelty of innovation, but has considerably smaller market. As such, there appears to be a

marked divergence in the approach adopted by the SMEs and large companies. One would be inclined to believe

that while large companies have capitalized on the most significant market opportunity, the majority of SMEs have

chosen to retreat to the next best available option.

A close scrutiny of the nature of innovation efforts involved in “clinical-functional” and "natural

functional" product categories provides an understanding into the potential reasons behind this divergence. Products

in the "clinical functional" category involve the use of active ingredients over which large companies have

proprietary rights, and the health related claims of these products are often validated by external, independent

research institutions. While products in the "natural functional" product category are based on general research and

knowledge and involve reformulation of existing ingredients and manufacturing processes. It, therefore, appears

reasonable to believe that the resource constraints faced by SMEs may have created encumbrances that prevented

them from capitalizing on this opportunity. Such an argument finds support in the "liability of smallness"

observations made by previous researchers. However, results of regression analysis had failed to provide support for

the fact that company type was related to company performance. This finding, when viewed with other findings of

this study created a paradoxical situation in which the SMEs appeared to suffer from a competitive disadvantage

compared to large firms, yet it was the nature of products innovation rather than the company type that appeared to

matter for company performance.

In order to find potential explanations for this dichotomy the researchers began an investigation into what,

if anything was done differently by those SMEs that did successfully introduce products in the Clinical Functional

product category. While not a part of the original study; this investigation appeared to be critical in understanding

the findings of this study. Although finding documented information about small companies is always a difficult

task, it was observed that many of the successful product introduction by SMEs involved the creation of some sort

of cooperative relationship with an external partner (such as a pharmaceutical company) or acquisition of proprietary

rights or patents from other value chain partners. In essence, these SMEs had created their own strategy to

overcome the "liability of smallness" in order to make successful strategic adaptations.

The Business Review, Cambridge * Vol. 16 * Num. 2 * December * 2010 54

Further review of the research literature on innovation revealed that the innovation pattern of these SMEs

followed what Chesbrough (2003) has described as the “open innovation model.” Companies that follow the open

innovation process adopt strategies that involve the use of external actors and sources to help them achieve and

sustain innovation. Recent studies have found that success of this model goes well beyond high technology, into

industries such as automotive, banking, finance, insurance, health care and consumer packaged goods (Laursen and

Salter, 2005). Although ex post facto in nature, but based on the results and investigative findings of this study it

would be reasonable to conclude that the way in which SMEs perceive and attempt to deal with their environment

has an important bearing on their innovation orientation and performance. However, since the data used in this

study did not include any information about resource availability, resource deployment, strategic decision making

process or organizational mechanism used to foster innovation, one can not be certain about this conclusion. But

however tentative, such a finding has important implications for SMEs attempting to make successful strategic

adaptations in the presence of large companies and needs to be examined in a more detailed and systematic way in

future studies.

Table 1 Results of Cluster Analysis: Strategic Orientation

Cluster Variable Prospectors Analyzers Defenders Reactors Total

(n=8) (n=9) (n=28) (n=17) (N=62)

Company Type

Large 8 0 0 0 8

SMEs 0 9 28 17 54

Number of Products 166 187 153 86 592

Natural Wellness 15 70 11 59 155

Organic 4 56 51 20 131

Natural Functional 35 30 86 7 158

Clinical Functional 112 31 5 0 148

Average Price* € 5.08 €4.81 €4.80 €3.86 --

(1.30) (1.30) (1.32) (0.59)

Sales Volume (in Kg)

Natural Wellness 662 2,508 74 3896 7,140

Organic 44 1,478 514 917 2,953

Natural Functional 153 2,392 2,438 492 5,475

Clinical Functional 45,757 4.992 3 0 50,751

Sales Value (in €)

Natural Wellness 3,169 10,479 280 16,558 30,486

Organic 135 6,629 2,194 3,379 12,337

Natural Functional 561 8,501 12,333 1,354 22,749

Clinical Functional 264,546 25,986 12 0 290,544

*standard deviations are in parenthesis.

Table 2 Company Type and Average Sales Volume, Sales Revenue, and Price in each Innovation Category

Innovation Natural Wellness Organic Natural Clinical Functional Total

Category Functional

Large SME Large Large Large Large

Company Size SME SME SME SME

Firm Firm Firm Firm Firm

Average sales

46.13 47.66 22.90 11.00 42.96 4.35 138.75 408.54 46.04 284.24

volume in Kg

Difference -1.53 11.90 38.61 -269.79 -238.2

t (n=592) -0.80 2.09* 5.43** -4.43*** -5.83***

Average sales in € 194.47 227.93 96.08 33.85 179.11 15.87 756.99 3,419.8 204.91 1,636.65

Difference -33.46 62.23 163.24 -2,662.8 -1,431.7

t (n=592) -0.34 3.17** 5.83** -4.73*** -6.05***

Average per Kg

4.32 4.45 4.63 3.06 4.69 3.63 5.08 5.68 4.58 5.08

price in €

Difference -0.13 1.57 1.06 -0.60 -0.50

t (n=592) -0.31 4.52** 4.28** -2.42** -4.13***

* significant at <.10 ** significant at <.05 *** significant at <.01

In a study conducted a few years ago it was noted that senior managers of SMEs, “tend to have a shorter

tactical rather than longer term strategic outlook” (Stewart-Knox and Mitchell, 2003). In a prescriptive way one can

conclude that SMEs need to develop a greater awareness of and willingness to adapt to the changes in the industry

environment, and in the process should not become focused too internally. To succeed in a dynamic industry

environment SMEs need to become more receptive to new product innovation opportunities and be able to act on

them by making the boundary between their firm and surrounding environment more porous (Chesbrough, 2003).

While one cannot entirely discount the importance of resource availability in a company’s innovation capability; the

The Business Review, Cambridge * Vol. 16 * Num. 2 * December * 2010 55

ability of SMEs to foster innovation has to begin with organizational supporting mechanism and decision making

processes that encourage them to open behavior in their efforts to capitalize on the innovation opportunities.

Table 3 Regression Results of the Determinants of Price Charged

Dependent Variable Price Charged

Independent Variables Coefficients

(Constant) 4.20 ***

(.27)

Innovation category .34 ***

(.05)

Company type -.15

(.13)

Sales volume .01

(.00)

Promotion -.02

(.00)

F 15.25 ***

R2 .10

N 592

*** significant at <.01, standard errors are in parenthesis

REFERENCES

AC Nielsen. Functional Foods and Organics, Sydney, 2005.

Ansoff HI, Stewart JM. Strategies for a Technology-based Business. Harvard Business Review 1967; 45: 71-83.

Boesso G, Davcik SD, Favotto F. Health-enhancing products in the Italian food industry: Multinationals and SMEs competing on yogurt.

AgBioForum 2009, 12(2): 155-66. Available on the World Wide Web: http://www.agbioforum.org.

Chen CJ, Huang JW. Strategic human resource practices and innovation performance-The mediating role of knowledge management capacity.

Journal of Business Research 2009; 62: 104-14.

Chesbrough HW. The Era of Open Innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review 2003; 44(3): 35-41.

Conant JS, Mokwa MP, Varadarajan P. Strategic types, distinctive marketing competencies and organizational performance: a multiple measures-

based study. Strategic Management Journal 1990; 11(5): 365-83.

Garret RP, Covin JG, Slevin DP. Market responsiveness, top management risk taking, and the role of strategic learning as determinants of market

pioneering. Journal of Business Research 2009; 62(8): 782-88.

Hambrick DC. Some tests of the effectiveness of functional attributes of Miles and Snow’s strategic types. Academy of Management Journal

1983; 26(1): 5-26.

Mckee DO, Varadarajan PR, Pride WM. Stratigic adaptibility and firm performance: a market-contingent perspective, Journal of Marketing 1989;

53(3): 21-35.

Miles RE, Snow CC. Organizational Strategy, Structure, and Process. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1978.

Laursen K, Salter, A. Open for innovation: The role of openness in explaining innovation performance among U.K. manufacturing firms,

Strategic Management Journal, 2006; 27:131-150.

Lord J B. New product failure and success. In A.L Brody, & J.B. Lord (Eds.), Developing new food products for a changing marketplace. USA:

Technomic Publishing, 1999.

Mark-Herbert C. Development and Marketing Strategies for Functional Foods. AgBioForum 2003; 6: 75-78. Available on the World Wide Web:

http://www.agbioforum.org.

O’Regan N, Ghobadian, A. Innovation in SMEs: the impact of strategy orientation and environmental perception. International Journal of

Productivity and Performance Management 2005; 54(2): 81-97.

Stewart-Knox B, Mitchell P. What separates the winners from the losers in new food product development. Trends in Food Science and

Technologies 2003; 14: 58-64.

Storper M. Regional worlds of production: learning and innovation in the technology districts of France, Italy and USA, Regional Studies 1993;

27(5): 433-55.

Wu J, Shanley MT. Knowledge stock, exploration, and innovation: Research on the United States electromedical device industry. Journal of

Business Research 2009; 62(4): 474-83.

The Business Review, Cambridge * Vol. 16 * Num. 2 * December * 2010 56

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

You might also like

- Parfums Cacharel de L'Oréal 1997-2007:: Decoding and Revitalizing A Classic BrandDocument21 pagesParfums Cacharel de L'Oréal 1997-2007:: Decoding and Revitalizing A Classic BrandrheaNo ratings yet

- Google 2020 E-Conomy SEA 2020 IndonesiaDocument18 pagesGoogle 2020 E-Conomy SEA 2020 IndonesiaFarjumzalNo ratings yet

- Wheelen Smbp13 PPT 01Document36 pagesWheelen Smbp13 PPT 01Ah BiiNo ratings yet

- 51 - Rewarding Special GroupsDocument10 pages51 - Rewarding Special GroupsmitalptNo ratings yet

- Corporate-Level Strategy: Three Key Issues Facing The CorporationDocument30 pagesCorporate-Level Strategy: Three Key Issues Facing The CorporationAshish ShuklaNo ratings yet

- Establishing A Customer FocusDocument5 pagesEstablishing A Customer FocusAditya KurniawanNo ratings yet

- Questionnaire DesignDocument24 pagesQuestionnaire Designशिशिर ढकालNo ratings yet

- Basil Dellor - Driving Innovation - CompletedDocument23 pagesBasil Dellor - Driving Innovation - CompletedEric Frempong AmponsahNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 - Race Without A Finish Line PDFDocument2 pagesCHAPTER 1 - Race Without A Finish Line PDFEduardo WanderleyNo ratings yet

- OrientationDocument8 pagesOrientationNitesh KhatiwadaNo ratings yet

- Ilham Habibie-Wantiknas-Audiensi Menteri BappenasDocument21 pagesIlham Habibie-Wantiknas-Audiensi Menteri BappenasumarhidayatNo ratings yet

- Wheelen 14e ch01Document40 pagesWheelen 14e ch01franky sunaryo100% (1)

- Strategic Intent 3Document22 pagesStrategic Intent 3niteshvnair100% (1)

- Wheelen 14e ch02Document33 pagesWheelen 14e ch02franky sunaryoNo ratings yet

- Business StrategyDocument23 pagesBusiness Strategywilsonngary100% (1)

- Economic Outlook 2021Document198 pagesEconomic Outlook 2021Die EwigkeitNo ratings yet

- PLN UIP Kitsum Quarterly SummitDocument37 pagesPLN UIP Kitsum Quarterly SummitEnggal FurniajiNo ratings yet

- 2022 Tech Education Day - Info DeckDocument10 pages2022 Tech Education Day - Info DeckAnonymous UpWci5No ratings yet

- How To Design A QuestionnaireDocument3 pagesHow To Design A QuestionnaireMithun SahaNo ratings yet

- Building Customer Satisfaction Through Quality, Service, and ValueDocument19 pagesBuilding Customer Satisfaction Through Quality, Service, and ValueHenry PamungkasNo ratings yet

- Strategic Management & Business Policy: Thomas L. Wheelen J. David HungerDocument35 pagesStrategic Management & Business Policy: Thomas L. Wheelen J. David HungerkishiNo ratings yet

- Economic Outlook 2023 OCE BMRIDocument21 pagesEconomic Outlook 2023 OCE BMRIjoenatan 2020No ratings yet

- External Environment Analysis of Airline IndustryDocument3 pagesExternal Environment Analysis of Airline IndustryJoey Tay100% (1)

- Strategic Management ModelDocument124 pagesStrategic Management Modelrocky_arunNo ratings yet

- Corporate StrategyDocument29 pagesCorporate StrategyIrene PonticelliNo ratings yet

- Orchestration of Network Slicing For Next Generation NetworkDocument76 pagesOrchestration of Network Slicing For Next Generation Networkchandan kumarNo ratings yet

- TomtomDocument9 pagesTomtomli100% (1)

- Driving Innovation and IdeasDocument30 pagesDriving Innovation and Ideastrial123No ratings yet

- Marketing Theory with a Strategic OrientationDocument12 pagesMarketing Theory with a Strategic OrientationNarmin Abida0% (1)

- Debt Collection Recovery Management Sea BankDocument4 pagesDebt Collection Recovery Management Sea BankPranav KhannaNo ratings yet

- The Strategy PaletteDocument11 pagesThe Strategy PaletteFathimaNo ratings yet

- Galanz's Operations Strategy for Future GrowthDocument11 pagesGalanz's Operations Strategy for Future Growthkokot123_100% (1)

- Summary of Vm#1 Customer FocusDocument6 pagesSummary of Vm#1 Customer FocusShekinah Faith RequintelNo ratings yet

- Contoh Five Forces AnalysisDocument17 pagesContoh Five Forces AnalysisChaeMJNo ratings yet

- Techniques For Analyzing Corporate Diversification StrategiesDocument7 pagesTechniques For Analyzing Corporate Diversification Strategiesapi-3738338100% (1)

- Traditional Consolidation End-Game Framework - v1.0Document12 pagesTraditional Consolidation End-Game Framework - v1.0batrarishu123No ratings yet

- Strategic Leadership: Michael A. Hitt R. Duane Ireland Robert E. HoskissonDocument29 pagesStrategic Leadership: Michael A. Hitt R. Duane Ireland Robert E. HoskissonDivya MalikNo ratings yet

- Indonesia e Conomy Sea 2021 ReportDocument17 pagesIndonesia e Conomy Sea 2021 ReportEep Saefulloh FatahNo ratings yet

- Hill & Jones - Ch03 - External AnalysisDocument19 pagesHill & Jones - Ch03 - External Analysisoushiza21No ratings yet

- Strategic Intent and Organizational VisionDocument21 pagesStrategic Intent and Organizational VisionAbhishek SoniNo ratings yet

- 8 Types of Business ManagementDocument3 pages8 Types of Business ManagementHerbert RulononaNo ratings yet

- War in Ukraine: Global Update: BCG Global Advantage Practice AreaDocument11 pagesWar in Ukraine: Global Update: BCG Global Advantage Practice AreaAyush MathurNo ratings yet

- DIGITAL 2020: IndonesiaDocument92 pagesDIGITAL 2020: Indonesia김연준No ratings yet

- Functional StrategyDocument35 pagesFunctional StrategyvishakhaNo ratings yet

- Agency Theory Family BusinessDocument8 pagesAgency Theory Family Businessusef100% (1)

- BCG MatrixDocument22 pagesBCG Matrixnomanfaisal1No ratings yet

- Ethical Issues in MarketingDocument30 pagesEthical Issues in MarketingDeepak KumarNo ratings yet

- Roland Berger Saudi Arabian Pharmaceuticals 2 PDFDocument20 pagesRoland Berger Saudi Arabian Pharmaceuticals 2 PDFVJ Reddy RNo ratings yet

- NTT Docomo Vol20 e en TotalDocument68 pagesNTT Docomo Vol20 e en TotalscribdenerNo ratings yet

- Chapter 5 The Five Generic ... StrategiesDocument20 pagesChapter 5 The Five Generic ... Strategieschelinti100% (1)

- Value Innovation PDFDocument12 pagesValue Innovation PDFDipankar GhoshNo ratings yet

- Slides Business Level StrategyDocument24 pagesSlides Business Level StrategyThảo PhạmNo ratings yet

- PP Ch03Document35 pagesPP Ch03FistareniNirbitaWardhoyoNo ratings yet

- Cost Leadership StrategyDocument11 pagesCost Leadership StrategyMahima GotekarNo ratings yet

- Blue Ocean Strategy For Medical and PharmaceuticalsDocument25 pagesBlue Ocean Strategy For Medical and PharmaceuticalsMohamed MahmoudNo ratings yet

- First Do No Harm Mar 2012 Tcm9-106817Document31 pagesFirst Do No Harm Mar 2012 Tcm9-106817nazNo ratings yet

- Radical Product Innovations in SMEs - The Dominance of Entrepreneurial Orientation PDFDocument15 pagesRadical Product Innovations in SMEs - The Dominance of Entrepreneurial Orientation PDFTitaneuropeNo ratings yet

- INFORMS Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Organization ScienceDocument22 pagesINFORMS Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Organization ScienceRachid El MoutahafNo ratings yet

- Evaluating Market Attractiveness: Individual Incentives vs. Industrial ProfitabilityDocument38 pagesEvaluating Market Attractiveness: Individual Incentives vs. Industrial ProfitabilityrerereNo ratings yet

- Karantininis, Sauer, Furtan, INNOVATION AND INTEGRATION IN THE AGRI-FOOD INDUSTRYDocument17 pagesKarantininis, Sauer, Furtan, INNOVATION AND INTEGRATION IN THE AGRI-FOOD INDUSTRYKostas KarantininisNo ratings yet

- Sustainable Innovation: The impact on the success of US large capsFrom EverandSustainable Innovation: The impact on the success of US large capsNo ratings yet

- Price, Value and Performance: Understanding the Tesla CaseDocument9 pagesPrice, Value and Performance: Understanding the Tesla CaseRodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- Aghion2009 PDFDocument20 pagesAghion2009 PDFRodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- Information Attention and Decision MakingDocument9 pagesInformation Attention and Decision MakingRodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- Mastering StrategyDocument2 pagesMastering StrategyRodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- MaslachScoringAbbreviated PDFDocument1 pageMaslachScoringAbbreviated PDFRatih AchiNo ratings yet

- Blue Ocean Strategy: Amazon Alexa CaseDocument10 pagesBlue Ocean Strategy: Amazon Alexa CaseMila SumpterNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence:: Implications For Business StrategyDocument12 pagesArtificial Intelligence:: Implications For Business StrategyWilliam PolhmannNo ratings yet

- Aghion2009 PDFDocument20 pagesAghion2009 PDFRodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- Hydroxychloroquine With or Without Azithromycin in Mild-to-Moderate Covid-19Document12 pagesHydroxychloroquine With or Without Azithromycin in Mild-to-Moderate Covid-19chamwick4567No ratings yet

- 2020.05.13.20094193v1.full 2Document22 pages2020.05.13.20094193v1.full 2Rodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- RP Requirements For Selection and Justification of Starting Materials For The Manufacture of CASDocument10 pagesRP Requirements For Selection and Justification of Starting Materials For The Manufacture of CASRodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- Artificial Intelligence:: Implications For Business StrategyDocument12 pagesArtificial Intelligence:: Implications For Business StrategyWilliam PolhmannNo ratings yet

- ICH Q2 R1 GuidelineDocument17 pagesICH Q2 R1 GuidelineRicard Castillejo HernándezNo ratings yet

- Analytical Procedures and Methods Validation For Drugs and Biologics - US FDA Final GuidanceDocument18 pagesAnalytical Procedures and Methods Validation For Drugs and Biologics - US FDA Final GuidanceDan StantonNo ratings yet

- QBD MaterialDocument5 pagesQBD MaterialRodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- E8043 M5a99fx Pro R2Document178 pagesE8043 M5a99fx Pro R2Rodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- MICLAB-110 Appendix 1 - Flow Chart For Processing Microbiology Laboratory OOS/OOL Investigations OOS/OOL Result GeneratedDocument1 pageMICLAB-110 Appendix 1 - Flow Chart For Processing Microbiology Laboratory OOS/OOL Investigations OOS/OOL Result GeneratedRodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- QBD PresentationDocument12 pagesQBD PresentationRodrigo BressanNo ratings yet

- Pre-Test - Performing The EngagementDocument2 pagesPre-Test - Performing The EngagementSHARMAINE CORPUZ MIRANDANo ratings yet

- 25-RBA (Responsible Business Alliance) Member - LenovoDocument3 pages25-RBA (Responsible Business Alliance) Member - LenovoHernani BergamoNo ratings yet

- ISB - GAMP Nov 2018Document12 pagesISB - GAMP Nov 2018reddyrajashekarNo ratings yet

- PettyferMichaelAKarl 2011 MonopoliesTheoryEffectivenessandRegulatiDocument151 pagesPettyferMichaelAKarl 2011 MonopoliesTheoryEffectivenessandRegulatiAndres IslasNo ratings yet

- Warehouse Management Software WMS System Selection RFP Template 2013Document217 pagesWarehouse Management Software WMS System Selection RFP Template 2013SusanLK100% (1)

- Basics of Business Mathematics in 40 CharactersDocument17 pagesBasics of Business Mathematics in 40 CharactersAbhishek JainNo ratings yet

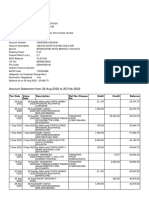

- Bank StatementDocument5 pagesBank StatementSANJIB GHOSHNo ratings yet

- Online Tutorial 8 Audit of Human Resources and Payment CycleDocument3 pagesOnline Tutorial 8 Audit of Human Resources and Payment CycleleiannetumamaoNo ratings yet

- Remedies in BankruptcyDocument34 pagesRemedies in BankruptcyfeyNo ratings yet

- The Application of Machine Learning and Deep LearnDocument20 pagesThe Application of Machine Learning and Deep LearnFran MoralesNo ratings yet

- Circular Guidelines and Schedule of Design Engineering Module ForDocument3 pagesCircular Guidelines and Schedule of Design Engineering Module ForAnmol KingNo ratings yet

- How To Use This Template: Delete This Slide Before Submitting Your AssignmentDocument11 pagesHow To Use This Template: Delete This Slide Before Submitting Your AssignmentAnnah AnnNo ratings yet

- SYZ Mining Audit Problem AnalysisDocument26 pagesSYZ Mining Audit Problem AnalysisKate NuevaNo ratings yet

- CA 08105001 eDocument3 pagesCA 08105001 eRicardo LopezNo ratings yet

- Saving Canada's Tallest TreeDocument7 pagesSaving Canada's Tallest TreeNarcisa Anabel Valeriano Veliz.No ratings yet

- Annual Report 2020-21Document121 pagesAnnual Report 2020-21Chhavi GajnaniNo ratings yet

- Work: Waterproofing Works For The Proposed 'Residential & Commercial Complex at Mohili, Sakinaka Mumbai 400 072' ContractorDocument11 pagesWork: Waterproofing Works For The Proposed 'Residential & Commercial Complex at Mohili, Sakinaka Mumbai 400 072' ContractorShubham DubeyNo ratings yet

- Trends in Ethics in Computing Assignment # 05 Sap Ids of Group MembersDocument2 pagesTrends in Ethics in Computing Assignment # 05 Sap Ids of Group Memberswardah mukhtarNo ratings yet

- Sales Order FormDocument1 pageSales Order FormDeepthireddyNo ratings yet

- Building International Brand Architecture: Integrating Branding Strategy Across MarketsDocument19 pagesBuilding International Brand Architecture: Integrating Branding Strategy Across MarketsDiana GuceaNo ratings yet

- Week 3 ModuleDocument14 pagesWeek 3 ModuleSofia Biangca M. BalderasNo ratings yet

- Which HR Bundles Are Utilized in Social Enterprises (Slide)Document2 pagesWhich HR Bundles Are Utilized in Social Enterprises (Slide)serofNo ratings yet

- European Union: Name - Ajay Bba - 6 SemesterDocument17 pagesEuropean Union: Name - Ajay Bba - 6 Semesterajay DahiyaNo ratings yet

- Swot of AbinbevDocument3 pagesSwot of AbinbevSanjeev Kumar SharmaNo ratings yet

- Group 9 Eabdm s13Document3 pagesGroup 9 Eabdm s13DIOUF SHAJAHAN K TNo ratings yet

- MPU3222 - Course Introduction Briefing For Student (Sem 1 - 2022-2023) (I)Document24 pagesMPU3222 - Course Introduction Briefing For Student (Sem 1 - 2022-2023) (I)trickyhunter9999No ratings yet

- Understanding Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) Introduction: Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) Are Complex Financial Transactions That InvolveDocument2 pagesUnderstanding Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) Introduction: Mergers and Acquisitions (M&A) Are Complex Financial Transactions That InvolveSebastian StolkinerNo ratings yet

- Group Assignment - A211 QUESTIONNAIREDocument9 pagesGroup Assignment - A211 QUESTIONNAIREMuhammad NafisNo ratings yet

- Exercise 1 Key PDF Cost of Goods Sold InvenDocument1 pageExercise 1 Key PDF Cost of Goods Sold InvenAl BertNo ratings yet