Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Perspective On Life Stress

Uploaded by

AnaSoareOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Perspective On Life Stress

Uploaded by

AnaSoareCopyright:

Available Formats

Social Safety Theory hypothesizes that developing and maintaining friendly social

bonds is a fundamental organizing principle of human behavior and that threats to social

safety are a critical feature of psychological stressors that increase risk for disease.

Central to this formulation is the fact that the human brain and immune system are

principally designed to keep the body biologically safe, which they do by continually

monitoring and responding to social, physical, and microbial threats in the environment.

Because situations involving social conflict, isolation, devaluation, rejection, and

exclusion historically increased risk for physical injury and infection, anticipatory neural–

immune reactivity to social threat was likely highly conserved. This neurocognitive and

immunologic ability for humans to symbolically represent and respond to potentially

dangerous social situations is ultimately critical for survival. When sustained, however,

this multilevel biological threat response can increase individuals’ risk for viral infections

and several inflammation-related disease conditions that dominate present-day

morbidity and mortality.

A fourth formulation, proposed by Clark & Beck (1999), is that stressors can be sorted

into different life domains, such as “interpersonal” (e.g., intimate relationship stressors)

and “achievement” (e.g., work-related stressors). A stressor's impact, in turn, is

heightened when a stressor matches the “content” of an individual's cognitive

vulnerability (e.g., a person with a rejection-sensitive negative cognitive schema gets

fired). A fifth hypothesis, described by Gilbert & Allan (1998), argues that direct social

conflict or competition that reduces social status, rank, value, or regard (i.e., defeat) is

the most deleterious quality of stressors. This could occur when an individual has a

major argument with a spouse or is subjected to persistent subordination or bullying.

Finally, a sixth perspective, offered by Brown & Harris (1978), is that stressors are

most impactful when they cause substantial cognitive upheaval or disruption to an

individual's goals, plans, or aspirations for the future (see also Carver & Scheier 1999).

From this viewpoint, getting fired would be a severe stressor if (for example) a person

worked for a company for a long time, had several coworkers as confidants, or had few

other financial resources or job prospects (Brown & Harris 1978).

Conceptual Conflict and Confusion

Although these theories have guided thousands of studies on life stress, several

problems are readily evident. First, with the exception of some minor similarities, these

formulations provide very different, largely nonoverlapping explanations for why certain

stressors are most impactful. Second, given how expensive and difficult it is to collect

extensive biological data on humans as they experience different stressors, these

theories are largely based on behavioral and clinical data, with researchers in turn

assuming how different stressors might affect underlying biological processes. Instead

of going from psychology to biology in this way, which has not been particularly fruitful, I

propose we try the opposite. Let's begin by asking what our biological systems care

most about and then use this information to inform the conceptualization of life stress.

To do this, I focus first on the human immune system and then on the brain.

THE HUMAN IMMUNE SYSTEM

Humans inhabit a world that is populated with numerous pathogenic microbes and

toxins that are constantly evolving and challenging our homeostasis. The primary goal

of the immune system, in turn, is to keep the body biologically safe and protected from

these foreign invaders and from physical injuries that could cause illness or death if left

unaddressed (Slavich & Irwin 2014). To accomplish this challenging task, the immune

system relies on a complex regulatory logic that evolved over millennia and that fine-

tunes itself based on input from the surrounding social, physical, and microbial

environment. Surviving such an environment requires the immune system to be well

calibrated to the specific types of threats that are most likely to be present.

Consequently, the human immune system starts off relatively undifferentiated during

infancy and becomes increasingly educated as a person ages. This process refines the

functional capacity and regulation of each individual's immune system and provides

humans with a highly evolved biological defense network that is critical for survival

(Rook et al. 2017).

You might also like

- Sesiones Programa SteppsDocument159 pagesSesiones Programa SteppsAndrea VC100% (8)

- Essentials of Breast Surgery (Sabel) PDFDocument347 pagesEssentials of Breast Surgery (Sabel) PDFCiprian-Nicolae Muntean100% (4)

- Brewerton. Clinical Handbook of Eating Disorders. An Integrated Approach PDFDocument604 pagesBrewerton. Clinical Handbook of Eating Disorders. An Integrated Approach PDFAna Sofia AlmeidaNo ratings yet

- Practical Radiotherapy Planning, Fourth EditionDocument477 pagesPractical Radiotherapy Planning, Fourth EditionMehtap Coskun100% (12)

- Cromwell Case Analysis, Inspiring Team, Section 2Document7 pagesCromwell Case Analysis, Inspiring Team, Section 2GoranM.MuhammadNo ratings yet

- Teoria de La Seguridad SocialDocument28 pagesTeoria de La Seguridad SocialMiguel Andres RangelNo ratings yet

- The Psychology of Self Defense: Self Affirmation Theory: David K. Sherman Geo Vrey L. CohenDocument60 pagesThe Psychology of Self Defense: Self Affirmation Theory: David K. Sherman Geo Vrey L. CohenKanji HisamotoNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER 1 SampleDocument17 pagesCHAPTER 1 SampleJames Bernard BeraniaNo ratings yet

- Taylor, S. E. (2011) - Affiliation and StressDocument11 pagesTaylor, S. E. (2011) - Affiliation and StresscaptacionrrhhNo ratings yet

- Stress 335Document6 pagesStress 335api-3699361No ratings yet

- 2013 14977 010Document10 pages2013 14977 010Catarina C.No ratings yet

- Psychological ResilienceDocument1 pagePsychological Resilienceguest0234No ratings yet

- About Vaccination. Two Needed ChangesDocument4 pagesAbout Vaccination. Two Needed ChangesferminjgmNo ratings yet

- Occupational Stress: Preventing Suffering, Enhancing WellbeingDocument12 pagesOccupational Stress: Preventing Suffering, Enhancing WellbeingandreaNo ratings yet

- Occupational Stress: Preventing Suffering, Enhancing WellbeingDocument11 pagesOccupational Stress: Preventing Suffering, Enhancing WellbeingSherlyn PedidaNo ratings yet

- Slavich - Psychoneuroimmunology - OxfordHandbook - in PressDocument50 pagesSlavich - Psychoneuroimmunology - OxfordHandbook - in PressDescargas 7No ratings yet

- Pages 152 Health PsychologyDocument9 pagesPages 152 Health Psychology22mpla31No ratings yet

- For Friday Article Review TwoDocument23 pagesFor Friday Article Review TwoDani Wondime DersNo ratings yet

- Usually It Takes Between 4 To 5 A4 Pages To Cover All The Requirements of The AsDocument2 pagesUsually It Takes Between 4 To 5 A4 Pages To Cover All The Requirements of The Ascrazyj03No ratings yet

- Biopolitical Technologies of PreventionDocument11 pagesBiopolitical Technologies of PreventionDanielle MoraesNo ratings yet

- Cicchetti ResilienceDocument10 pagesCicchetti ResiliencePamela SilvaNo ratings yet

- Schaller / Evolutionary Bases of First Impressions 1Document15 pagesSchaller / Evolutionary Bases of First Impressions 1Sriraj DurailimgamNo ratings yet

- Trauma Violence Abuse 2013 Ungar 255 66Document12 pagesTrauma Violence Abuse 2013 Ungar 255 66LauraLunguNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Trauma On The Developing Brain:: A Literature ReviewDocument18 pagesThe Impact of Trauma On The Developing Brain:: A Literature ReviewN. Alexandra KovacsNo ratings yet

- Resilience Theory Lit ReviewDocument28 pagesResilience Theory Lit Reviewapi-383927705100% (1)

- A Study On The Relationship Between Tenacity and Sychological Components On SecurityDocument6 pagesA Study On The Relationship Between Tenacity and Sychological Components On SecurityinventionjournalsNo ratings yet

- Disaster Preparation and Recovery. Lessons From Research On Resilience in Human DevelopmentDocument16 pagesDisaster Preparation and Recovery. Lessons From Research On Resilience in Human DevelopmentZuluaga LlanedNo ratings yet

- Map 510 Capstone Reflection - RJ MontesDocument7 pagesMap 510 Capstone Reflection - RJ Montesapi-635328971No ratings yet

- What Is Resilience: An Affiliative Neuroscience ApproachDocument19 pagesWhat Is Resilience: An Affiliative Neuroscience ApproachiNoahGH SaYHelloToONo ratings yet

- Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: An Open Access JournalDocument14 pagesHealth Psychology and Behavioral Medicine: An Open Access JournalViviana PueblaNo ratings yet

- EpidemiologyDocument10 pagesEpidemiologyAri Pebrianto AliskaNo ratings yet

- Resilience in ChildrenDocument27 pagesResilience in Childrenapi-383927705No ratings yet

- McCroryViding TheoryofLatentVulnerabilityDocument14 pagesMcCroryViding TheoryofLatentVulnerabilityFenrrir BritoNo ratings yet

- Lippincott Williams & Wilkins Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Medical CareDocument13 pagesLippincott Williams & Wilkins Is Collaborating With JSTOR To Digitize, Preserve and Extend Access To Medical CareMónica MartínezNo ratings yet

- Chunilal Mandal Paper2Document12 pagesChunilal Mandal Paper2Surbhi RawalNo ratings yet

- Running Head: ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAY 1: Argumentative Essay: Vaccines Do More Good Than HarmDocument7 pagesRunning Head: ARGUMENTATIVE ESSAY 1: Argumentative Essay: Vaccines Do More Good Than HarmKennedy Gitonga ArithiNo ratings yet

- Resilience in AgingDocument23 pagesResilience in AgingAna Flavia CondeNo ratings yet

- Final Copy of Sustainability ProgramDocument17 pagesFinal Copy of Sustainability ProgramREADS RESEARCHNo ratings yet

- En Wikibooks OrgDocument3 pagesEn Wikibooks Orgmahirajmahi0% (1)

- 15Document16 pages15Jojo MarinayNo ratings yet

- BIology, SES and HealthDocument4 pagesBIology, SES and HealthBethy OreroNo ratings yet

- Psychological Resilience Hope and Adaptability As Protective Factors in Times of Crisis A Study in Greek and Cypriot Society During The Covid 19 Pandemic 'PDF'Document15 pagesPsychological Resilience Hope and Adaptability As Protective Factors in Times of Crisis A Study in Greek and Cypriot Society During The Covid 19 Pandemic 'PDF'Demetris HadjicharalambousNo ratings yet

- Stress and Coping MechanismsDocument17 pagesStress and Coping MechanismsKrishnan JeeshaNo ratings yet

- Guttman - On Being Responsabile - Health CampaignDocument20 pagesGuttman - On Being Responsabile - Health CampaignColesniuc AdinaNo ratings yet

- Galea 2012 Causal Thinking and Complex System Approaches in EpidemiologyDocument10 pagesGalea 2012 Causal Thinking and Complex System Approaches in EpidemiologyPrevencion AtencionNo ratings yet

- Coping Competencies What To Teach and WhenDocument10 pagesCoping Competencies What To Teach and WhenjuancaviaNo ratings yet

- Document Introduction StressDocument10 pagesDocument Introduction StressHardeep KaurNo ratings yet

- Resilience, Competence, and CopingDocument5 pagesResilience, Competence, and CopingBogdan HadaragNo ratings yet

- Judges' Journal 2014 Domestic Violence - Impact On Children - NeuroscienceDocument6 pagesJudges' Journal 2014 Domestic Violence - Impact On Children - NeuroscienceLegal Momentum100% (1)

- The Mind-Body Connection: Not Just A Theory Anymore: Social Work in Health Care February 2008Document22 pagesThe Mind-Body Connection: Not Just A Theory Anymore: Social Work in Health Care February 2008Muhammad Ali Ridwan TanjungNo ratings yet

- Intergenerational Transmission of Stress in HumansDocument14 pagesIntergenerational Transmission of Stress in HumansAlejandro BrunaNo ratings yet

- Topic 3:: "The Greatest Weapon Against Stress Is Our Ability To Choose One Thought Over Another"-William JamesDocument8 pagesTopic 3:: "The Greatest Weapon Against Stress Is Our Ability To Choose One Thought Over Another"-William JamesZetZalunNo ratings yet

- What Do I Do Now - Intolerance of Uncertainty Is Associated With Discrete Patterns of Anticipatory Physiological Responding To Different Uncertain ContextsDocument49 pagesWhat Do I Do Now - Intolerance of Uncertainty Is Associated With Discrete Patterns of Anticipatory Physiological Responding To Different Uncertain ContextsMIGUEL ANGEL JIMENEZ HUERTASNo ratings yet

- The Economics of VaccinationDocument34 pagesThe Economics of Vaccinationthedevilsoul981No ratings yet

- Work Stress and Resident Burnout Before and DuringDocument12 pagesWork Stress and Resident Burnout Before and Duringmarcelocarvalhoteacher2373No ratings yet

- Vivekananda College (University of Delhi) : Organizational behaviour-II Practical TOPIC: Organisational Role StressDocument30 pagesVivekananda College (University of Delhi) : Organizational behaviour-II Practical TOPIC: Organisational Role StressSrishti GaurNo ratings yet

- Resilience in Common Life Introduction TDocument8 pagesResilience in Common Life Introduction TGloria KentNo ratings yet

- Wolfendale 2017Document18 pagesWolfendale 2017Federico AbalNo ratings yet

- Reino UnidoDocument10 pagesReino UnidoaxNo ratings yet

- The Power of ResilienceDocument11 pagesThe Power of ResilienceNayanaa VarsaaleNo ratings yet

- Health Belief Model UpdateDocument15 pagesHealth Belief Model Updatejust nomiNo ratings yet

- Epistemic HealthDocument26 pagesEpistemic Healths.juklNo ratings yet

- Science, The Basic Problem and Human SecurityDocument15 pagesScience, The Basic Problem and Human Securityvladi324No ratings yet

- Ncm102 Purposive Assignment RSRCHDocument44 pagesNcm102 Purposive Assignment RSRCHleehiNo ratings yet

- Agents Classified by The IARC Monographs, Volumes 1-131Document40 pagesAgents Classified by The IARC Monographs, Volumes 1-131AnaSoareNo ratings yet

- Billion-Dollar Business: Research Quarterly That Assessed Evidence OnDocument2 pagesBillion-Dollar Business: Research Quarterly That Assessed Evidence OnAnaSoareNo ratings yet

- Brain DevelopmentDocument1 pageBrain DevelopmentAnaSoareNo ratings yet

- MindfulnessDocument1 pageMindfulnessAnaSoareNo ratings yet

- Investigating The English Language Needs of Petroleum Engineering Students at Hadramout University of Science and TechnologyDocument31 pagesInvestigating The English Language Needs of Petroleum Engineering Students at Hadramout University of Science and TechnologyAnaSoareNo ratings yet

- Baumé Scale SayboltDocument20 pagesBaumé Scale SayboltAnaSoareNo ratings yet

- Bolile Cerebro-Vasculare Accidentul Vascular CerebralDocument66 pagesBolile Cerebro-Vasculare Accidentul Vascular CerebralAnaSoareNo ratings yet

- Breast Anatomy PDFDocument64 pagesBreast Anatomy PDFpartha9sarathi9ainNo ratings yet

- 33 Special Types of Invasive Breast Carcinoma Diagnostic CriteriaDocument255 pages33 Special Types of Invasive Breast Carcinoma Diagnostic CriteriaAnaSoareNo ratings yet

- Law Enforcement Operation and Planning With Crime MappingDocument2 pagesLaw Enforcement Operation and Planning With Crime MappingLuckyjames FernandezNo ratings yet

- 01-People - Psychology - CXL Institute PDFDocument1 page01-People - Psychology - CXL Institute PDFEarl CeeNo ratings yet

- An Overview of Sigmund Freud's TheoriesDocument13 pagesAn Overview of Sigmund Freud's TheoriesChi NguyễnNo ratings yet

- Egaña, Jericho A. - Activity #2Document5 pagesEgaña, Jericho A. - Activity #2Jericho EganaNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Classification of Psychopathology: DSM Iv TR: StructureDocument17 pagesUnit 2 Classification of Psychopathology: DSM Iv TR: StructureAadithyan MannarmannanNo ratings yet

- Specific Learning DisabilitiesDocument44 pagesSpecific Learning DisabilitiesNeeti Moudgil100% (1)

- Instant Transformational Hypnotherapy by Marisa Peer 0731Document13 pagesInstant Transformational Hypnotherapy by Marisa Peer 0731Cristi Ungureanu100% (3)

- Orthographic Coding in Illiterates and Literates: Jon Andoni Duñabeitia, Karla Orihuela, and Manuel CarreirasDocument7 pagesOrthographic Coding in Illiterates and Literates: Jon Andoni Duñabeitia, Karla Orihuela, and Manuel CarreirasprasanthNo ratings yet

- John R. Campbell & Alan Rew Ed., Identity and Affect - Experiences of Identity in A Globalising World (Anthropology, Culture and Society), 1999 BookDocument318 pagesJohn R. Campbell & Alan Rew Ed., Identity and Affect - Experiences of Identity in A Globalising World (Anthropology, Culture and Society), 1999 BookManray HsuNo ratings yet

- Confilct Management Chapter5Document31 pagesConfilct Management Chapter5botchNo ratings yet

- Discussion TextDocument2 pagesDiscussion Texthappy jungNo ratings yet

- POM - MODULE 6 (Ktuassist - In)Document20 pagesPOM - MODULE 6 (Ktuassist - In)sree_guruNo ratings yet

- 1.0 Introduction To Personal Development - 2Document35 pages1.0 Introduction To Personal Development - 2Pol Vince Bernard SalisiNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Team by Delicia Ann SDocument3 pagesMental Health Team by Delicia Ann SDelicia SohtunNo ratings yet

- Leadership ArchetypesDocument18 pagesLeadership ArchetypesIt's Just MeNo ratings yet

- Behavior Unconditioned Vs Conditioned StimuliDocument2 pagesBehavior Unconditioned Vs Conditioned StimuliTaylorNo ratings yet

- OB Unit-1Document18 pagesOB Unit-1cat lostNo ratings yet

- Dosey Meisels 1969 Personal Space and Self-ProtectionDocument5 pagesDosey Meisels 1969 Personal Space and Self-ProtectionMikeFinnNo ratings yet

- ConformityDocument3 pagesConformityAyse KerimNo ratings yet

- Psy 1303 - Psychological Report Assessment DetailsDocument1 pagePsy 1303 - Psychological Report Assessment DetailsMorish Roi YacasNo ratings yet

- The Intersubjective Mirror in Infant Learning and Evolution of Speech Advances in Consciousness Research PDFDocument377 pagesThe Intersubjective Mirror in Infant Learning and Evolution of Speech Advances in Consciousness Research PDFJuliana García MartínezNo ratings yet

- Job Satisfaction ProjectDocument36 pagesJob Satisfaction ProjectGulam Hussain79% (24)

- Assignment Defense MechanismsDocument4 pagesAssignment Defense MechanismsJamoi Ray VedastoNo ratings yet

- Miluu Miliquu Afaan Oromoo Fiction by GuDocument160 pagesMiluu Miliquu Afaan Oromoo Fiction by GuBilisuma chimdesaNo ratings yet

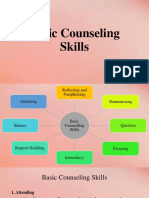

- Lesson On Counselling (Basic Skills On Counselling)Document11 pagesLesson On Counselling (Basic Skills On Counselling)Alliyah PantinopleNo ratings yet

- Factores Protectores y de Riesgo Del Trastorno de Conducta TdahDocument17 pagesFactores Protectores y de Riesgo Del Trastorno de Conducta TdahLourdes CisnerosNo ratings yet

- Count Ur Chicken Before They Hatch - BookDocument30 pagesCount Ur Chicken Before They Hatch - BookPranjal Jain60% (5)