Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Coasean Theory of Property Rights and Law Revisited: A Critical Inquiry

Uploaded by

Giannis TsilligirisOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Coasean Theory of Property Rights and Law Revisited: A Critical Inquiry

Uploaded by

Giannis TsilligirisCopyright:

Available Formats

Science & Society, Vol. 82, No.

1, January 2018, 38–66

Coasean Theory of Property Rights and

Law Revisited: A Critical Inquiry

GIORGOS MERAMVELIOTAKIS and

DIMITRIS MILONAKIS

ABSTRACT: Ronald Coase’s famous Theorem states that e xternalities

— third‑party effects of transactions that undermine the supposed

optimality of competitive equilibrium — do not need to be cor-

rected by active government policy, as in the classical presentation

by A. C. Pigou, if there are complete markets in property rights. This

Theorem, however, is inherently flawed, as revealed by “internal”

or “immanent” critique of its assumptions. It thus fails, even on its

own terms. Beyond this, however, a more radical critique, which

foregrounds issues of social structure, social relations, power and

conflict, forms the basis for a comprehensive analysis of (capitalist)

property rights. This radical analysis of the Coase Theorem and

the debate spawned by it has implications for the entire field of

“law and economics” studies, and for its central notion that legal

doctrine can be based on any set of pure efficiency criteria.

1. Introduction

I

N HIS CLASSIC 1960 ARTICLE, “The Problem of Social Cost,”

Ronald Coase is the first among the new institutionalists to try to

incorporate the issues of property rights and transaction costs into

economic analysis. He unfolds his argument regarding the issue of how

ownership arrangements, which generate external effects, can drive the

system into an efficient allocation of resources. In particular, he exam-

ines the economic implications of the allocation of legally delineated

rights, namely those that have external effects on the value of other

individuals’ abilities to exercise their rights over assets. The basic feature

of his analysis is the notion of transaction cost. Coase argues that the

38

G4595.indd 38 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 39

function of the market per se is not without costs: “there is a cost of using

the price mechanism” (1988a, 38). He identifies three sorts of costs:

first, “the most obvious cost . . . is that of discovering what the relevant

prices are.” The other two types of transaction costs refer to “the costs

of negotiating and concluding a separate contract for each exchange

transaction which takes place on market” and the costs associated with

the establishment of long-term contracts (ibid., 38–39). In his other

major article, Coase (1988a, 114–115), he clarifies the concept further.

Transaction costs include the costs of discovering “who it is that one

wishes to deal with, to inform people that one wishes to deal and on

what terms, to conduct negotiations leading up to a bargain, to draw

up the contract, to undertake the inspection needed to make sure

that the terms of the contract are being observed, and so on.” And he

concludes that transaction costs are “the cost of carrying out market

transactions . . .” Coase uses the notion of transaction cost as a bench-

mark to divide his analysis into two distinct parts. In the first part, he

attempts to identify the essence of property rights in the “imaginary”

frictionless world of zero transaction costs; in the second, he tries to

explain the allocation of the legally enacted property arrangements in

the “real” world of positive transaction costs. In the former case, Coase

erects what is universally known as the Coase Theorem, while in the

latter he lays the foundations of the economic analysis of law.

One can easily discern in Coase’s analysis the foundation of mod-

ern neoliberal economics, with the underlying core idea that the

market itself is the only mechanism that can produce efficient results.

Thus, any government intervention will hinder the efficient operation

of the free market and will lead to inefficient allocation of resources.

In this vein, Simpson (1996, 58–63) identifies three basic ideas in

Coase’s economic analysis of law. First is the reciprocal nature of social

cost problems where both parties involved are assumed to cause the

damage. Second is the “as if market” (indispensible) role of law in a

real world of positive transaction costs, which should allocate rights in

the same way as the market. Last is an economic, cost–benefit analysis

in deciding how to solve problems of social cost.

In what follows and in the context of “internal critique” we focus

on what we regard as the main foundational weaknesses of Coase’s

economics as expressed in the 1960 article. Thus, the analytical sub-

stance and strength of the Coase Theorem even in a frictionless world

of zero transaction costs is brought into question on the grounds of its

G4595.indd 39 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

40 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

tautological nature, the existence of important theoretical gaps from

a game-theoretic perspective, and its logically and empirically wrong

premise with regard to the separation of the issues of efficiency and

distribution. Second, Coase’s economic analysis of law is found to be

in direct contradiction with (and hence violating) the de jure nature

of institutionalized rights over property and hence leading to ineffi-

cient results both in static and in dynamic terms. Last, and chiefly, in

the penultimate section, a more radical, Marxist critique of Coase’s

analysis is brought to bear based on an alternative methodological

and theoretical framework involving issues of social structure, social

relations, power and conflict. We argue that the aforementioned social

factors are the sine qua non condition for a comprehensive analysis of

(capitalist) property relations.

2. The Externality Problem

The point of departure of Coase’s analysis is the externality prob-

lem. The term “externality” refers to a consequence upon a third

party of the action or activity of another individual. These external

effects on the third party may be either harmful or beneficial. So, the

problem arises because, in the presence of externalities, the allocation

of resources is inefficient and, consequently, a mechanism of inter-

nalization of externalities (i.e., a mechanism through which the costs

and benefits do not diffuse into the wider economy but are absorbed

by the productive and consuming activities that generate them) is

necessary in order to allocate resources efficiently.

The traditional economic approach to the externality problem

can be traced back to mainstream welfare economics associated with

Pigou’s (1962 [1932]) analysis. The best-known example is the situ-

ation where a factory produces pollution, a negative externality to

the surrounding neighborhood. The neighborhood’s loss is a form

of social cost, but the factory will not take this cost into account in

making its own production decisions. Since behavior is assumed to

be based on private costs and benefits, externalities may give rise to

an inefficient allocation of resources. The Pigovian solution is that

government should interfere through the use of a punitive tax to cor-

rect the negative externality. By taxing the factory, society can force it

to face the social cost (the pollution) that it generates. The purpose

of this tax is to make the social become part of the private cost. In

G4595.indd 40 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 41

this way, the externality will be internalized and resources will then

be allocated efficiently from society’s viewpoint.

The Pigovian solution to the externality problem is based on

two strong intuitions. The first is that Pigovian welfare economics

encounters the externality problem from a moral viewpoint. Based

on conventional notions of causation — the traditional dichotomy

between the party that causes the harm (the factory) and the victim

(the neighborhood) — Pigou’s approach inevitably tries to make the

victim whole and “punish” the party that generates the externality.

The second intuition refers to the mechanism that internalizes the

externalities: use of state intervention through taxes, subsidies, or

regulations to alter the behavior (i.e., abate the activities) of the party

causing the externality. In his way the Pigovian approach lays empha-

sis on the role of government interference in the economic sphere.

Coase took the discussion into a different direction by reversing

the Pigovian analysis of the externality problem. First, he challenged

Pigou’s moral viewpoint by pointing out that an externality problem,

in reality, is reciprocal in nature:

The traditional approach has tended to obscure the nature of the choice

that has to be made. The question is commonly thought of as one is which

A inflicts harm on B and what has to be decided is, How should we restrain

A? But this is wrong. We are dealing with a problem of a reciprocal nature.

To avoid the harm to B would be to inflict harm on A. The real question that

has to be decided is, Should A be allowed to harm B or Should B be allowed

to harm A? The problem is to avoid more serious harm. (Coase, 1960, 96.)

In other words, while it is true that there would be no harm to the

members of the neighborhood in the absence of the factory’s pollu-

tion, it is equally the case that there would be no harm to the neigh-

borhood if the members of the neighborhood were not located in the

vicinity of the factory. Consequently, Coasean analysis, in contrast to

Pigou’s theory, changes the moral basis by altering the conventional

notion of causation. There is no longer a victim that must be made

whole and a victimizer who must be punished; just two potential vic-

tims (and beneficiaries), the question being to minimize the overall

cost inflicted upon and distributed between them.

Coase goes on to suggest that, being reciprocal in nature, the prob-

lem of externalities is also amenable to efficient resolution without state

G4595.indd 41 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

42 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

intervention. According to Coase, in a well-functioning capital system,

the internalization of externalities can be accomplished by the trans-

fer of relevant property rights between the affected parties. In other

words, contrary to Pigou’s reliance on government interference, Coase

proposed a market-oriented solution to the externality problem, through

free trade in property rights. This statement forms the core of one of

the most controversial theorems in economics, the Coase Theorem.

3. The Coase Theorem

In the first part of “The Problem of Social Cost,” Coase’s analysis

refers to a world of zero transaction costs and points out that externali-

ties will be internalized by a mutually beneficial bargain, between the

producer of externalities and the victim, irrespective of the initial alloca-

tion of property rights. His argument was named “the Coase Theorem”

by Stigler1 and opened a new direction in the field of welfare economics.

One important assumption of the Coase Theorem is that when

externalities are present, the affected parties can negotiate directly and

costlessly in order to resolve the conflict. Contrary to Pigou’s reliance

on state interference, which ignored the role of private property rights,

Coase shows how free trade in rights can lead to an efficient allocation

of resources, if markets operate without frictions. This requires that

three conditions be met. First is a clear specification of property rights:

the Coase Theorem presupposes ex ante fully delineated private prop-

erty rights. It should be stressed that in Coasean discourse, the concept

of property rights is reduced to explaining ownership arrangements

in terms of person-to-thing relations. In this way, property rights are

defined simply in terms of the actions that people are able to exercise

in relation to the things they own. This means that either the party

who generates the externality has the legal right to do it, or the victim

has the legal right to be compensated for the harmful effect produced

by the other party.2 Second are fully alienable property rights. This

1 “I did not originate the phrase, ‘the Coase Theorem,’ nor its precise formulation, both

of which we owe to Stigler” (Coase, 1988c, 157). Note that both Stigler and Coase were at

Chicago and fanatical supporters of free markets, especially at the micro level, with Stigler

campaigning for the Nobel Prize for Coase and for Ernest Becker.

2 It is worth noting that the Coase Theorem does not provide either a mechanism to explain

how these rights came into existence, or any device to demonstrate how these rights are

allocated. Coase attempts to provide a mechanism to justify the efficient allocation of prop-

erty rights in the second part of his article, where he deals with the role of law in a positive

transaction costs world.

G4595.indd 42 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 43

means that the affected parties are free to “exchange” their rights

until a Pareto-efficient allocation of resources has been attained. Any

restriction that hinders the trade of these rights makes the Coasean

market-oriented solution potentially inefficient. Last, but not least, the

Coase Theorem presupposes that transaction costs are zero: “This is the

essence of the Coase Theorem . . . making clear that [the Theorem]

was dependent on the assumption of zero transaction costs” (Coase,

1988c, 158). In other words, the costs of negotiating, monitoring,

acquiring information and enforcing contractual agreements are zero.

Granted these conditions, Coase demonstrates that a market-oriented

solution, based on a free trade of rights between affected parties, will

bring about an efficient allocation of resources. This is the efficiency

hypothesis of Coase’s theorem (Medema and Zerbe, 2000, 838).

To support his theorem, Coase (1960, 97–104) used the example

of an economic conflict between a cattle raiser and a wheat farmer

about the rights to use land. More concretely, the example refers to

the case of straying cattle, which destroy crops growing on neighbor-

ing land. It is assumed that there is no fencing between the neighbor-

ing properties and an increase in the size of the cattle-raiser’s herd

increases the total damage to the farmer’s crops. There is no way that

the farmer himself can prevent the damage to his crop. Suppose,

further, that the cattle-raiser’s profits and the value of damages to the

farmer’s crops associated with various quantities of cattle are as given

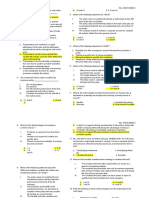

in Table 1 (see next page).

Table 1 is an extension of Coase’s original table (1960, 97). The

first, fourth and filth columns are the same as those in Coase’s table,

while the others will help us to understand the “theorem” more fully.

The last column represents net social benefit as the sum of cattle-

raiser’s profit and farmer’s profit (for simplicity we assume that farm-

er’s profit is constant and equals 8), minus the annual crop loss. The

Pareto optimum point, where the net social benefit is maximized, is

at 3 steers. Therefore, the efficient allocation of resources is achieved

when the cattle-raiser has 3 steers in his herd.

Coase’s example assumes that a cattleman grazes his cattle next

to crops owned by a farmer on neighboring land. Using the pricing

system (which is without cost), any damage to the crops would be paid

by the cattle owner. Specifically, costs could be represented as in Table

1. Also, the cost of fencing the farmer’s property is $9 and the price

of the crop is $1 per ton. The options available if the cattle owner is

G4595.indd 43 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

44 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

TABLE 1

Number in Cattle Cattle Raiser’s Annual Crop Loss per Net

Herd Raiser’s Profit per Crop Additional Social

(Steers) Profit Additional Steer Loss Steer Benefit

1 10 10 1 1 17

2 18 8 3 2 23

3 24 6 6 3 26

4 26 2 10 4 24

held liable for property damage are the following: If the cattle owner

chooses to increase his herd from 2 to 3 steers, then the cost imposed

would be $3 to pay for the additional crops damaged. The cattle owner

will not add additional steers unless the return for that steer is more

than $3. If the cattle owner wants to have a herd of 4 steers, it would be

cheaper (than the total of $10 for crop loss) for him to pay for fencing

the farmer’s field. Coase argues that if the presence of the cattle owner

has any effect on the amount of crops planted, it would be that the

farmer would plant less. It may get to a point that the receipts from the

undamaged crops would be less than the cost of planting. Therefore,

the final outcome will be the efficient point of 3 steers. However, Coase

shows in his example that the same outcome would occur if the cattle

owner was not held liable for crop damage. Therefore, the farmer would

have to pay the cattle owner for not adding steers to his herd (or hav-

ing fewer steers), pay for the fencing, or quit planting crops. He states

“it is necessary to know whether the damaging business is liable or not

for the damage caused, since without the establishment of this initial

delimitation of rights there can be no market transactions to transfer

and recombine them. But the ultimate result (which maximizes the

value of production) is independent of the legal position if the pricing

system is assumed to work without cost” (Coase, 104).

The Coase Theorem states that irrespective of the initial alloca-

tion of rights (i.e., whether the damage is liable to the cattle-raiser,

which means that the farmer has the right to “clear” crops, or the

cattle-raiser has no liability for the damage and hence has the right

to “damage”) the externalities (the damage caused by the straying

cattle on neighboring land) will be internalized. This means that

the efficient allocation of resources between the cattle-raiser and the

farmer will not depend on the initial allocation of property rights:

G4595.indd 44 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 45

It is necessary to know whether the damaging business is liable or not for

damage caused, since without the establishment of this initial delimitation

of rights there can be no market transactions to transfer and recombine

them. But the ultimate result (which maximizes the value of production) is

independent of the legal position if the pricing system is assumed to work

without cost. (Coase, 1960, 104.)

This is the invariance hypothesis of the Coase Theorem (Medema and

Zerbe, 2000, 838).

The conclusion is that in a situation of zero transaction costs, the

two agents can resolve their conflict by trading their rights. When rights

become tradable they enjoy a market value and a market price will be paid.

Such a rearrangement of rights, however, will only be undertaken when

the increase in the value of production consequent upon the reallocation

of rights is greater than the costs, which would be involved in bringing it

about; i.e., there is bargaining room for the affected parties to negotiate a

level of payment (a price in the special case of a market) that internalizes

the externalities and hence leads to an efficient allocation of resources.

4. An “Immanent” Critique of Coase’s Theorem

The purpose of this section is to provide an “immanent” or

“inside” critique of Coase’s theorem. In other words, our attempt is

to question and challenge the analytical validity of the theorem on its

own terms. In this vein, the analytical substance and strength of the

theorem even in a frictionless world of zero transaction cots is brought

into question on grounds of its tautological nature, the existence of

important theoretical lacunae from a game-theoretic perspective, and

its logically and empirically false premises with regard to the separa-

tion of the issues of efficiency and distribution.

i. The Tautological Character of Coase’s Theorem. The Coase Theo-

rem triggered an endless debate among mainstream economists. A

voluminous literature is the result, much of it devoted to attacking

or defending the Theorem.3 The stickiest issue in the debate is the

3 For example, Wellisz (1964) argues that the Theorem under perfectly competitive conditions

in the long run presupposes rents that may not exist. Similarly, Regan (1972) and Veljanovski

(1982) point out that even if the Coase reasoning is valid in the short run, there will be changes

in allocation of resources in the long run. On the other hand, Calabresi (1968) notes that in

the presence of determined conditions Coase’s conclusions remain as true in the short run

as in the long run. Much of this literature is discussed in Medema and Zerbe (2000).

G4595.indd 45 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

46 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

precise meaning given to the assumption of zero transaction costs.

Just what counts as a transaction cost?

Elsewhere we have tried to lay bare the vague and ill-defined nature

of the concept of transaction costs (see Meramveliotakis and Milonakis,

2010). For Coase (1937, 38–9; 1960, 114) transaction costs explicitly

encompass all of the ex ante and ex post costs of accomplishing a contract.

These include the negotiation and bargaining costs of concluding a mutu-

ally beneficial arrangement as well as enforcement and policing costs.

On closer inspection, it turns out that in this all-encompassing defi-

nition, anything that prevents reaching a mutually advantageous bargain

is a transaction cost. If so, the absence of transaction costs means that

no such obstacle to reaching a bargain exists, and the parties involved

would then be able to negotiate an efficient solution to the problem.

The Coase Theorem can, then, be restated as follows: “Individuals will

make efficient bargains if no obstacle of any kind to such bargaining

exists.” Presumably, if individuals do not reach a mutually advantageous

bargain, some obstacle has prevented them from doing so. A mutually

beneficial outcome will be achieved in the absence of transaction costs,

where the latter are interpreted to be any hindrances to bargaining,

whether literally costs of bargaining, or other obstacles, such as asym-

metries of information between bargaining parties. Granted this, the

strength and appeal of the Coase Theorem is based on an overextension

of the transaction costs concept to the point of absurdity.

If transaction costs thus defined are zero, the beneficial outcome

is assured ex hypothesi. This, however, reduces the theorem to a mere

tautology. This is because the notion of transaction costs is defined so

that the absence of transaction costs assures the efficient outcome, in

the sense that if there are gains from trading rights and trading is com-

pletely costless, then trading will take place to everyone’s advantage.

But, if transaction costs are zero, no externalities would ever occur,

since they will be dealt with instantaneously as soon as they emerge.

As Usher (1998, 9) concludes: the idea

that resources will be employed efficiently in the absence of transaction cost

is almost a tautology. What does it mean to say that transaction costs are zero?

It means that people can bargain costlessly, and will, presumably, do so as

long as bargains are mutually advantageous. But the absence of mutually

advantageous bargains is precisely what one means by efficiency, a state of

affairs such that no change can make one person better off without making

somebody else worse off. The strictly-correct version of the Coase Theorem

G4595.indd 46 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 47

boils down to the proposition that if people can agree upon an efficient

outcome, then there will be an efficient outcome.

To costless bargaining should be added the timeless nature of the

world of Coase’s theorem.

ii. A Critique from a Game-Theoretic Perspective. Coase’s theorem

implies — assuming zero transaction costs and fully delineated and

alienable property rights — that the externality problem is resolved

through a bilateral bargaining process between the affected parties

which leads to an efficient outcome. The a priori nature of this argu-

ment is obvious. Coase assumes that in all cases the agents agree a

price for the externality and for the right that maximizes the net

social benefit.4 At this point Coase commits an error. He presupposes

that the agents will inevitably reach an agreement as the result of

the bargaining process, in order to justify the efficient outcome that

maximizes the value of production. But this cannot just be taken for

granted; it has to be explicitly shown. In fact, from a game-theoretic

perspective, Coase’s theorem is a tautology and as such true by defi-

nition, only if a pure coordination game is assumed. In the case of a

strategic game, the theorem loses its tautological character and the

agreement is no longer necessarily the outcome of the bargaining

process, even in the absence of transaction costs.

The first to notice this weakness was Samuelson (1967), quoted

in Coase (1988c). Samuelson explicitly questioned Coase’s idea that

bilateral bargaining a priori leads to a mutually satisfactory agreement,

even under the assumption of a frictionless world. In his reply to

Samuelson, Coase (1988c, 160) first argues that Edgeworth’s classic

analysis provided the underlying logic of his own:

Edgeworth has argued in Mathematical Psychics (1881) that two individuals en-

gaged in exchanging goods would end on the “contract curve” because if they

did not, there would remain positions to which they could move by exchange

which would make both of them better off. Edgeworth implicitly assumed that

there was costless “contracting” and “recontracting”; and I have often thought

that a subconscious memory of the argument in Mathematical Psychics, which

I studied more than fifty years ago may have played a part in leading me to

formulate the proposition which has come to be termed the “Coase Theorem.”

4 In the Coase Theorem, however, this price remains unspecified. Different prices correspond

to different allocations of the exchange surplus.

G4595.indd 47 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

48 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

Following this, Coase asserts that it is natural to believe that rational

agents will end up with a mutual agreement because it is in their

common interests to do so: “I would not expect the parties to choose

terms which make both of them worse off than they need to be” (161).

However, the argument Coase invokes to justify the efficiency

outcome of the negotiation process can be refuted from a game-

theoretic bargaining perspective. First, it fails to take into account

that the agents act strategically in the game, i.e., their behavior takes

into account the expected behavior of the other player and the

mutual recognition of interdependence. This means that the inter-

action between the cattle-raiser and the farmer is one of strategic

interdependence, and hence that one’s rewards are positively cor-

related with the other’s losses. Following this, Cooter (1982, 23)

argues that the possibility of strategic behavior disproves the Coase

Theorem because this behavior can prevent efficient bargains despite

the absence of transaction costs:

The error in the bargaining version of the Coase Theorem is to suppose that

the obstacle to cooperation is the cost of communicating, rather than the

strategic nature of this situation. Bargainers remain uncertain about what

their opponents will do not because it costs too much to broadcast one’s

intention, but because strategy requires that true intentions be disguised.

Thus, Coase seems to overlook the case where individuals have the

incentive to cover their real intentions, thus raising the possibility of

non-cooperation.

Second, each individual, as a rational self-interested actor, tries to

maximize his/her own utility with regard to the exchange surplus and

not the entire social surplus. These observations lead us to formulate

a different game, which is characterized by a mixture of coordination

and conflict. Knight (1992, 52) pinpoints that

these mixed-motive cases . . . have multiple equilibria that, unlike the pure

coordination cases, differ in their payoffs for the various players. Because of

these distributional differences, the actors differ in their preference ranking

of the available equilibria. For example, player A prefers outcome 4,2 to 2,4,

whereas player B’s preferences are just the opposite. Although both prefer

coordination on one of the two equilibria, as opposed to the nonequilibrium

alternatives, they disagree on which outcome should be achieved. Therefore,

there is no assurance that the rational pursuit of self-interest will lead to

G4595.indd 48 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 49

an agreement, and hence there is the possibility of a situation in which no

equilibrium outcome exists.5

In contrast to Coase’s assumption concerning the efficiency of

the negotiations, the conclusion drawn from the above is that the par-

ties may not contract in a mutually beneficial manner, because either

bargaining scenarios will not necessarily induce the parties to reveal

their true preferences or because each of them wants to achieve social

outcomes that give them distributional advantage, which means that

bargains may not be optimal even in the context of a frictionless

world. Thus, only given the existence of an authority or institutional

mechanism to force individuals to achieve an agreement, they might

adopt reciprocal hostile positions like those envisaged by Hobbes

(threats, attacks, etc.) rather than cooperative behavior (Regan, 1972;

Cooter, 1982).

Coase (1998b, 161) seems to concede the possibility of an inef-

ficient outcome of the bargaining process, arguing that “it is certainly

true that we cannot rule out such an outcome if the parties are unable

to agree on the terms of exchange, and it is therefore impossible to

argue that two individuals negotiating an exchange must end up on

the contract curve, even in a world of zero transaction costs” (emphasis

added). Nevertheless, he insists on the truth of his Theorem by invok-

ing its empirical relevance. Specifically, Coase believes that inefficient

bargaining outcomes are too rare to have much significance: “. . . there

is good reason to suppose that the proportion of cases in which no

agreement is reached will be small.” But simply supposing that many

bargains occur does not in itself provide any information about what

possible bargains fail to occur. In any case, recourse to pragmatism is

no substitute for theoretical argument.

Coase’s argument has been subjected to both empirical and exper-

imental tests.6 However, it is highly questionable if such exercises

have any validity, given the unrealistic assumption of zero transaction

costs. In other words, the Coase theorem per se is incapable of being

tested given the unrealistic nature of zero transaction costs. This can

explain the inconsistency between experimental results and empirical

5 For a different perspective see Farrell, 1987.

6 See, for example, Hoffman and Spitzer, 1982; Ellickson, 1986; and Donohue, 1989, among

others. For a review of the experimental and empirical studies of the Coase Theorem see

Medema and Zerbe, 2000, 858–873.

G4595.indd 49 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

50 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

findings. For instance, both Ellickson’s (1986) and Donohue’s (1989)

findings are inconsistent with Coase’s theorem, while Hoffman and

Spitzer’s (1982) experiments do confirm Coase’s predictions in large

measure.

iii. The Issue of Distribution. One underlying presupposition of the

Coase Theorem is that distribution does not matter for efficient out-

comes. The world of the Coase Theorem is distributionally blind.

Coasean analysis only looks at the net benefits (total social benefits

minus total social costs) to the entire community but not at the distri-

bution of these benefits. Thus, a central proposition of Coase’s analysis

is that issues of distribution and efficiency can be separated, and the

efficiency of the market outcome does not depend on the distribution

of wealth, so long as there are well-defined property rights.

Although the initial assignment of rights is neutral with respect

to the pursuit of optimal resource use, it is not neutral with respect

to the distribution of wealth between the two parties. This should be

clear from the nature of the bargaining between the farmer and the

rancher under the two assignments described above. For example,

when the farmer initially had the right to prevent the cattle straying,

it was the rancher who paid the farmer for the right to increase his

herd up to the efficiency point. In contrast, when the rancher initially

had the right, the farmer paid the rancher to reduce his herd down

to the efficient point. In both cases, the herd size ended up being

the same, but the distribution of wealth favored the party who held

the initial right. Thus, whoever receives the right first is better off.

In other words, the issue of efficiency is totally separated from

distributional questions; i.e., how the pie is cut is different from how

it grows, so that the market is believed to be able to generate efficient

outcomes independent of “who gets what.” But although the solution

reached is not affected by the initial distribution of property rights,

the same is not true for the resulting distribution of wealth between

the parties involved.

It should be noted that in Coase’s analysis efficiency is defined in

general terms, as the attainment of the greatest aggregate social value.

Throughout his article, Coase never uses the term Pareto efficiency.

Indeed it seems that Coasean efficiency refers chiefly to the notion

of Kaldor–Hicks efficiency, which is not concerned with whether or

not a reallocation of resources makes certain individuals worse off,

but rather with whether or not society’s aggregate utility has been

G4595.indd 50 12/6/2017 9:30:58 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 51

maximized.7 This suggests that an exchange is efficient if it makes at

least one person better off, and the person who benefits is capable of

compensating any disadvantage to others. Thus, Kaldor–Hicks effi-

ciency might seem to be more compatible with Coase’s analysis than

the Pareto concept. But if this is so, then the issue of distribution is

not without significance, since Kaldor–Hicks efficiency introduces a

principle of distribution and this is a critical concession. Kaldor–Hicks

efficiency, by definition, is not distributionally blind.

It follows that frictionless bargaining does not necessarily lead to

maximization of social welfare if wealth is not distributed in a socially

desirable way. Suppose, for instance, that a party does not possess

wealth sufficient to pay for a socially desirable change in another

party’s behavior. Take the example of a multinational firm that makes

a profitable chemical product, but in so doing, dumps noxious waste

into a common-access lake used for subsistence fishing by local resi-

dents of a developing country. If the multinational has been granted

property rights to pollute, it may be impossible for local residents to

purchase rights to the lake from the multinational if they are poor.

Hence, even from a Coasean, positive perspective, an efficient solu-

tion to the problem cannot be reached due to wealth and income

considerations.

It follows further that distribution matters and not just for who

gets what, but also for how much there is to be got. This implies that

issues of distribution cannot be separated from issues of efficiency,

since the size of the cake depends, among other things, on how it is

cut. It is therefore fallacious to pursue social policy simply in terms

of efficiency considerations.8

5. Law and Property Rights

In the second part of his article, Coase relaxes the unrealistic

assumption of zero transaction costs and begins to tackle liability law

from a more pragmatic perspective:

7 On Kaldor–Hicks efficiency, see Kaldor, 1939; Hicks, 1939.

8 The separation of the issues of efficiency and distribution has also been subject to critical

scrutiny from a new information-theoretic perspective by Joseph Stiglitz (1994). According

to Stiglitz (1994, 45–50), whether or not the economy is Pareto efficient can depend on the

distribution of income, implying that one cannot ignore the distributional consequences

of policy.

G4595.indd 51 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

52 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

The argument has proceeded up to this point on the assumption that there

were no costs involved in carrying out market transactions. This is, of course,

a very unrealistic assumption. In order to carry out a market transaction, it is

necessary to discover who it is that one wishes to deal with, to inform people

that one wishes to deal and on what terms, to conduct negotiations leading

up to a bargain, to draw up the contract, to undertake the inspection needed

to make sure that the terms of the contract are being observed, and so on.

These operations are often extremely costly, sufficiently costly at any rate to

prevent many transactions that would be carried out in a world in which the

pricing system worked without cost. (1960, 114.)

So, once Coase recognizes this important aspect of how the real world

works, he attempts to provide a supplementary analysis in order to take

into account the existence of positive transaction costs. Initially, he points

out that when the costs of carrying out market transactions are taken into

account, it is clear that the rearrangements of rights through the market

may not lead to a Pareto efficient outcome: “the costs of reaching the

same result by altering and combining rights through the market may

be so great that this optimal arrangement of rights, and the great value

of production which it would bring, may never be achieved” (115).

The rearrangement of rights will only be undertaken when the

increase in the value of production consequent upon the rearrange-

ment is greater than the costs involved in bringing it about. When it

is less — affected parties cannot proceed with negotiations that will

lead to an economically “efficient” state of affairs and the private

solution becomes impossible — Coase states explicitly that, under

these conditions, the initial delimitation of rights over externalities

does have an effect on the efficiency with which the economic system

operates.9 This means that in a situation where a production activity

generates negative externalities, the internalization of these externali-

ties is strictly subject to the initial allocation of property rights (i.e.,

which of the parties “owns” the right), since severe transaction costs

block the affected parties from entering into a bargaining process.

At this point, Coase begins to tackle an issue that is at the core

of the analysis of the New Institutional Economics. He suggests an

approach to the problem of the efficient allocation of property rights:

9 We use the term “rights over externalities” in order to define two distinct cases. First is the

case where the victimizer “has the right” to produce the externalities, and, second is the

case where the victim “has the right” to be free of them.

G4595.indd 52 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 53

the situation is quite different when market transactions are so costly as to

make it difficult to change the arrangement of rights established by the law.

In such cases, the courts directly influence economic activity. (1960, 119.)

Here, Coase stresses the role of law in defining and establishing prop-

erty arrangements over externalities. It follows that courts should

assign property rights (or legal entitlements) directly to the most

efficient users in a way that minimizes the costs associated with the

externality in order to achieve an efficient allocation of resources.

Coase thus lays the foundations of the economic analysis of law.

He offers a criterion whereby disputes over externalities can be adju-

dicated through an efficient assignment of property rights. Justice

itself should be subordinated to efficiency. He thus began to colonize

a new field by injecting into the field of law the economist’s method

of cost–benefit analysis, thus opening the ground for a new subfield

known as “law and economics.” Coase’s economic theory of law could

be considered as one of the first instances of economics imperialism

(see also Fine and Milonakis, 2009, 99–106).10

Coase lists numerous examples from court decisions arising out of

the common law relating to nuisance. His endeavor is to illuminate his

theory by recording a number of cases, while simultaneously clarifying

his opposition to the Pigovian tradition. For instance, he cites a case

from English legal history, Sturges v. Bridgman (1879) (1960, 105–7).

A confectioner’s machinery disturbs a neighboring doctor. Hence, a

negative externality is present, while high transaction costs restrain

the affected parties from solving the dispute through a free trade of

rights. Thus, the court’s decision to assign the property rights is crucial

to ensure economic efficiency. According to Coase (106), the court’s

decision depends “essentially on whether the continued use of the

machinery adds more to the confectioner’s income than it subtracts

from the doctor’s.” If it adds more income to the confectioner, then

the court has to assign the right to continue to operate the machine.

On the other hand, if the doctor’s income would have fallen more

through the use of this machinery than it added to the income of the

confectioner, then the court should give the right to the doctor to

prevent the confectioner from using his machinery.

10 The logic of economics imperialism is to expand economic analysis to other social sciences.

In other words, economic analysis is used for the investigation of social phenomena. For a

critical discussion of economics imperialism, see Fine and Milonakis, 2009.

G4595.indd 53 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

54 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

The problem which we face in dealing with actions which have harmful ef-

fects is not simply one of restraining those responsible for them. What has

to be decided is whether the gain from preventing the harm is greater than

the loss which would be suffered elsewhere as a result of stopping the action

which produced the harm. (132.)

The Coasean logic in the assignment of rights stresses the recip-

rocal nature of the externality problem and is opposed to the unidi-

mensional notion of causation prevalent in the Pigovian approach to

externalities. Following the latter, the court would act to protect the

victim–doctor and restrain the harm-causing confectioner by provid-

ing the right to the doctor.

Summarizing, Coase points out that in the presence of positive

transaction costs, the way property rights are enacted affects the alloca-

tion of resources. Consequently, the role of law is to allocate property

rights in a way that ensures economic efficiency, hence distancing

himself from the legal notion of justice, the moral principle that

makes the victim whole and punishes the victimizer. The common-

law adjudication and judicial control of property should, according

to Coase, be inherently associated with the efficiency principle.

6. A Critique of Coase’s Economic Theory of Law

In Coase’s opinion, the goal of the judge is not to provide justice

in the legal sense (i.e., make the victim whole and punish the victim-

izer), but rather to maximize social wealth. This view of law, based

on utilitarian morality, which Coase envisioned, renders to the legal

decision-makers the authority to assign rights in ways that maximize

the value of society’s output (efficiency principle). Because the Coa-

sean approach is embedded in the tradition of positive economics,

it demonstrates a lack of interest in notions of fairness and justice.

Its sole concern is with instrumental market efficiency (optimum

productive uses of resources, those that maximize social welfare or

social utility). In Coase’s world the role of law resembles the role of the

market. The task of the former is not to prevent the harm afflicted in

cases of property disputes, but rather to assign rights over externali-

ties to the party which has more to gain either by their presence or

their absence, in the same way that a free market would. When judges

distribute rights in the way that an ideal market would, they, like the

G4595.indd 54 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 55

market, are maximizing total social wealth. As such, Coase offers an

“as if market” utilitarian type of argument as the (novel) basis of law.

In what follows, however, we point out that Coase’s proposal for

an “as if market” analysis of law in the delimitation of rights over exter-

nalities, based on utilitarian morality, contradicts the very nature of

rights over capitalist property, hence undermining some fundamental

principles of the bourgeois juridical system. Specifically, Coase’s whole

argument is based on an infringement of basic rights and legal entitle-

ments over property that are normally associated with the institution

of property.11

Let us return to the classic example, the dispute between the

cattle-raiser and the farmer. We assume that transaction costs block

any negotiations between the parties and, hence, a judge has to decide

if the cattle-raiser is liable or not for the damage. Coase proposes

that the judge should decide his verdict by using a strictly economic

criterion (market efficiency). If, for example, the cattle-raiser pro-

duces an extra 100, while the farmer loses because of the presence of

externalities only 50, so the net social benefit is raised by 50, then the

judge should decide that the cattle-raiser is not liable for the damage.

If the reverse happens, the cattle raiser is liable for the damage and,

hence, must compensate the farmer.

This comes into direct contradiction with the (usual but not abso-

lute) legal connection between causality and responsibility.

Coase appears simply not to accept the common law notion of causation

as a means of assigning responsibility. That someone “causes” a nuisance

(as determined by common law principles) does not, in his view, imply the

efficiency of holding this person responsible. (Duxbury, 1998, 187; see also

Simpson, 1996, 60.)

Indeed Coase (1960, 112) is explicit about this lack of connection

between the two: “If we are to discuss,” he says, “the problem in terms

of causation, both parties cause the damage.” This is a corollary of

Coase’s treatment of such questions on an “as if market” basis. Again

he is explicit:

11 As Cooter observes, “besides the ownership of resources, the law creates many other entitle-

ments, such as the right to use one’s land in a certain way, the right to be free from nuisance,

the right to compensation for tortuous accidents, or the right to performance on a contract”

(1987, 64).

G4595.indd 55 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

56 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

If we are to attain an optimum allocation of resources, it is therefore desirable

that both parties should take the harmful effect (the nuisance) into account

in deciding their course of action. It is one of the beauties of a smoothly

operating pricing system that . . . the fall in the value of production due to

the harmful effect would be a cost for both parties.

Out goes legal (and ethical) reasoning, in comes the efficiency logic

as a basis of solving disputes over tort and rights.

Such a perspective, however, based on a cost–benefit criterion of

gains and losses, neglects the fact that an institutionalized (legally enacted)

structure of private rights over an asset is already in existence. Particularly,

in the case where the cattle-raiser is not liable for the damage caused,

the farmer’s (legal) rights over his property are severely violated, since

Coase’s “as if market” approach to law does not provide any reaction

mechanism (e.g., some form of compensation) for the trespassing of

the farmer’s property.12 Coase, in other words, denies “Pigou’s claim

that the common law concept of causality is a useful guide to assigning

responsibility” (Cooter, 1987, 69). For the farmer’s rights to be real,

however, any violation of these rights must somehow be accounted

for (e.g., compensated). If not, then these rights may just as well be

taken as non-existent. A right is a right if it is acted upon as such. If

not, it loses its legal basis as a right.

Hence, in the Coasean “as if market” argument, use of the crite-

rion of economic efficiency as the driving principle for the allocation

of rights over the externalities infringes the victim’s (in our example,

the farmer’s) rights over his property. Following Coase’s proposal,

the judge’s decision based solely on an efficiency criterion does not

take into account the farmer’s (legal) rights and entitlements over his

property. The farmer’s rights over his property are not recognized as

such, but simply as an ex post derivative of the judge’s decision, and only

in the case where the production of externalities reduces net social

wealth. Only in this case the cattle-raiser is liable for the damage and

12 In discussing a real case of a dispute between a railroad company, whose coal-fired engine

emits sparks, and a farmer whose field may be set on fire by these sparks, Coase (1960, 138)

explicitly states that “it is not necessarily desirable that the railway should be required to

compensate those who suffer damage by fires caused by railway engines.” In Coase’s legal

world, the farmer’s refusal to allow the railroad company to set fire to his crops is seen as

imposing economic damage on the railroad company, a damage which may be greater than

the damage imposed on the farmer by the engine that spews out sparks, hence leading to

reduced social utility.

G4595.indd 56 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 57

the farmer has the right to receive compensation. On the contrary,

if the production of externalities does not reduce social wealth, then

the cattle-raiser is not liable and hence the victim of the violation is

not compensated.

The conclusion is that while Coase tries to erect an economic

theory of law in situations of property rights disputes, the result is that

his proposed theory drives out the legal basis of property rights. In

Coase’s legal world, these rights simply lose their de jure status. Not only

that. Coase’s theory is also in direct contradiction with the very essence

and nature of the notion of capitalist private property right itself, since

it violates the idea of “exclusivity” as the prima facie condition for the

operationalization of private property in practice. In Coase’s theory,

the “right to exclude,” to use North’s terminology (1981, 21), is not a

(legal) right exercised by the owner (or even attenuated by the state

for purposes of public interest) but, on the contrary, it is infringed

due to the fact that it is not enforced in practice. The farmer has no

ex ante (de jure) right to exclude the cattle-raiser from his property,

other than when, following the court’s decision, this exclusion leads to

an efficient result! In other words, in the Coasean world, (exclusive)

capitalist private property rights are not so “private” after all, and

certainly not “exclusive.”

Another drawback of Coase’s economic (cost–benefit) approach

to law is that even with such a restricted view of rights, which are

simply a function of changes in total social wealth, his valuation

of social welfare is synonymous to market (monetary) valuation.

Hence, all factors of value to the individual other than monetary

ones are not taken into account. Assuming, for instance, that in the

position of the “victim” is not a farmer who cultivates crops, but an

individual who cultivates flowers in his garden with purely aesthetic

value for him. This means that there is no market value for these

flowers. Cows from a neighboring field trespass the agent’s property

and destroy the flowers. The judge, following the Coasean logic, will

always decide in the cattle-raiser’s favor, since there is no market

value for the flowers raised for purely aesthetic purposes; hence,

the production of externalities increases social wealth measured

purely in monetary terms. The implication is that the “as if market”

approach of law accepts only market values in the delimitation of

property rights over externalities, a very crude basis for a legal sys-

tem to operate on.

G4595.indd 57 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

58 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

7. Towards a More Radical Perspective: A Marxist Critique

So far, the endeavor has been to reveal the internal methodologi-

cal problems and theoretical drawbacks of Coase’s analysis in both

parts of his work. For a more radical critique, however, we need to

move beyond Coase’s own framework. Built as it is on the premises

of marginalism, methodological individualism and micro-rationality,

Coase provides an analytical framework that fails to incorporate in a

comprehensive manner any reference to social structures and rela-

tions, power and conflict. Thus, the impact of property rights on the

behavior of economic actors, is causally associated with cost–benefit

calculations of (more or less) rationally acting individuals. In this

vein, any attempt to explain institutional formations suffers from

the substantial problems that Coase has inherited from the asocial

approach of neoclassical economics.

Granted these problems, an alternative theoretical framework

for the analysis of institutions in general, and of (capitalist) property

rights in particular, seems necessary. Such a framework should be

built on different methodological and theoretical premises. In order

to construct such a theoretical framework, the social should be taken

as the point of departure in the form of social relations, structures,

interests, power and conflict. It is, thus, argued that the aforemen-

tioned social factors are a sine qua non condition of a comprehensive

analysis of institutions and property rights.

i. Methodological Individualism and Social Structure. One basic meth-

odological foundation of Coase’s analysis is the principle of method-

ological individualism, that is, the perception that the individual (and

his/her choices) has analytical priority over social structure and other

social processes. In this vein, all social phenomena (including property

rights, their structure and their change) are explicable by recourse to

individuals, their traits, goals, convictions and actions (Elster, 1982,

48). In this conception, social structure has no objective existence,

independently of the social consciousness and acts of individuals.

Individuals (bodies, organisms, and their associated cognitive and

behavioral capacities) are real, while society, social structures and

collectivities are not real at all, but are simply considered as gather-

ings of individuals.

However, a social structure constitutes the set of relations in

which people participate, whether they wish to or not, because of the

G4595.indd 58 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 59

centrality of these relations to the production and reproduction of

social life. These social relations can be acknowledged or unacknowl-

edged by the individuals involved, but do not depend on the identity of

the particular agents (individual traits and attitudes), and they appear

as “external” to any given human action, although not external to

all the individuals involved (Hodgson, 2004, 12; Callinicos, 2004, 38;

Giddens, 1984, 16; Fine and Milonakis, 2009, 154). Social structure

as a concept is used to capture the objectively identified properties

exhibited by social entities and to specify the objectively identified

positions among their component elements. “Objectively identified”

refers to the idea that a structural property does not depend on the

ideas or actions of any single individual (Fine and Milonakis, 2009,

154). Seen from this perspective, social structure is described as a set of

empty places, the terrain in which social relations and practices in the

form of actual activities of individuals fill the slots (Wright, 1979, 21).

In such a framework, social structure acquires analytical primacy

over individual action, since the latter should be considered in the

context of social relations in which people participate in a given social

structure. The fact that human beings act with aim and purpose does

not mean that history represents an exclusive fulfillment of that will.

Instead, historical change may come about behind the backs of human

actors, often with unintended consequences. As Marx (1904 [1858],

11–12) has famously argued:

In the social production which men carry on they enter into definite rela-

tions, that are indispensable and independent of their will. . . . It is not the

consciousness of men that determines their existence, but, on the contrary,

their social existence determines their consciousness.

Basic to the argument here is that, appearances to the contrary,

property is not defined as a relation between an individual and a

thing, itself a nonsensical conception, but rather as a social relation

between people. As such, it is an emphatically historically determined

category. As Sayer (1987, 60) puts it,

in previous forms of society, neither individuals as owners, nor their property,

had their modern exclusivity or simplicity. Property did not even appear as

a simple relation of person and thing. Who owned what, or even what it

meant to be an owner, were by no means clear-cut; the very terms at issue

are anachronistic.

G4595.indd 59 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

60 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

All this changes with capitalism when capitalist ownership becomes a

de jure well-defined property. Talking about capitalist ownership rather

than private property also points directly to the social character of this

ownership, involving chiefly relations between classes. In this way capi-

talist ownership assumes its real substance as a bearer of antagonistc

class relations, an issue to which we now turn our attention.

ii. Social Relations and Social Conflict. Coase’s analysis overlooks the

fundamental social relations involved in any property arrangement.

The totality of social relations is reduced to the level of contractual

exchange relationships among individuals governed by the universal

law of the minimization of transaction costs. Thus, social relations

are reduced to exchange relations, which are in turn reduced to the

same underlying principle governing the actions of individuals. They

all attempt to minimize transaction costs, irrespective of their social

position.

What is missing from this approach is the fact that the individual

is always part of a social whole and is molded by the underlying social

relations according to the social position the individual occupies. As

Marx (1993 [1857], 264–265) argues,

society does not consist of individuals, but expresses the sum of inter-relations,

the relations within which these individuals stand. . . . To be a slave, to be a

citizen, are social characteristics, relations between human beings, A and B.

Human being A as such, is not a slave. He is a slave in and through society.

Property involves social-structural properties, and as such an alter-

native theoretical framework must fully integrate the totality of social

relations. For this we have to move away from the Coasean concep-

tions of social relations formed exclusively at the level of individual

exchange towards a deeper analysis of the structural elements of the

societal whole as an essential starting point for the analysis of capital-

ist property rights.

Further, Coase conceives society as a network of voluntary con-

tractual relations and analyzes the economy in particular in terms of

contractual agreements among atomized individuals. In particular,

the emergence and evolution of institutions and property rights are

elucidated on the grounds of the deliberate and voluntary personal

decisions taken by individuals. Hence, institutional formation is

explained in terms of voluntary contractual agreements based on

G4595.indd 60 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 61

the transaction costs minimization principle. Under these theoreti-

cal givens, the underlying assumption is that society embodies a

fundamental level of “harmony of interests” that always eventually

leads to beneficial “mutual agreements” between the contracted

parties.13

Such a premise, however, is a violent (unreal) abstraction, since in

society in general, and in the economy in particular, interests cannot

in principle be conceived as homogeneous or identical, but rather

should be conceptualized as structural, conflictual and antagonistic

interests between classes. As Marx (2001 [1847], 109) argues, social

conflict is not vested primarily at the individual level, but is, at bottom,

a structural class conflict, since

social relations are based on class antagonism. These relations are not rela-

tions between individual to individual, but of workman to capitalist, of farmer

to landlord, etc. Wipe out these relations and you annihilate all society.

In this vein, social conflict is a pervasive phenomenon and one of

the most important catalysts of social change. Hence, an alternative

theoretical framework has to move beyond the underlying idea of

“harmony of interests,” according to which institutional formation is

brought about through a process of repeated harmonious voluntary

contracts between individuals. This suggests that the issue of social

conflict is a prima facie ontological condition for a coherent analysis

of (capitalist) property rights.

iv. Power and Power Relations. In Coase’s work the issue of power and

power relations is totally absent. In the liberal camp, as already seen,

the notion of power is conceptualized and treated analytically in an

exclusively individualistic fashion. This individualistic notion of power

also flourishes in the game-theoretic approaches, describing situations

involving interactions between two or more agents with conflicting

goals and with the ability to influence each other. In such a context,

power analysis is restricted exclusively to the level of the individual

in a bargaining context (bargaining power), i.e., to the capacity of an

13 The idea of “harmony of interests” was developed also by Carey (1868), whom Marx described

as “the most banal and therefore the most successful representative of the vulgar-economic

apologetic.” Carey tries to demonstrate the presence in capitalist society of a complete har-

mony of real and genuine interests. The foundation of his theory of the “identity of interests”

was built on the (very questionable) assumption that wages increase in accordance with the

increase in labor productivity.

G4595.indd 61 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

62 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

agent to achieve his/her goals relative to somebody else. This notion

is contained at the level of micro theory, where the notion of power

concerns the economic agents’ aspiration to maximize their individual

utility function by subordinating other agents’ behavior and resources

controlled by them (Bartlett, 1989, 5).

However, even this form of power at the level of individual agents

cannot be understood simply by considering their atomistic relations

without reference to the wider social context in which they interact.

The individualistic conception of power, while an important aspect

for a theory of social institutions and property rights, is nevertheless

too restrictive, since it is the asymmetrical distribution of power at

the social level that lies behind the relations of power at an interper-

sonal level. Consequently, although an agent may have power (this

form of power may imply direct physical power or greater income

power or even power to influence an opinion) within an interac-

tion situation or “game” (e.g., greater ability than others to select a

preferred outcome or to realize his/her will over others within that

social structural context), s/he may or may not have the power to

alter the “type of game” the actors play, the rules and institutions

and related conditions governing interactions or exchanges among

the actors involved.

It therefore becomes apparent that one has to move beyond the

“individualistic” conception of power to something more embracing.

This calls for a systemic notion of power, referring to a socially struc-

tured capacity enabling actions by individuals, groups and classes by

virtue of their location within the web of social relations. In this way,

the analysis of power is not restricted exclusively to the level of the

individual, but takes into account the way in which society is organized

and expresses itself in relationships of domination and exploitation.

Seen from this angle, each social formation (feudalism, capitalism,

etc.) comprises a level of systemic power and forms a certain nexus of

power relations among classes, groups and individuals. In this perspec-

tive, social relations embody power relations expressed as a structure

of domination and subordination that is never static but always subject

to contestation and struggle.

Moreover, systemic power does not merely operate within struc-

tural settings but also organizes and reproduces the settings them-

selves. Consequently, systemic power shapes the framework of social

relations and influences (or modifies) property relations.

G4595.indd 62 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 63

8. Concluding Remarks

In this article we have brought to the fore a number of important

lacunae and drawbacks of Coase’s theory. In the context of “immanent

critique,” we pointed out its tautological character stemming from the

all-encompassing meaning given to the assumption of zero transac-

tion costs. Furthermore, arguing from a game-theoretical perspective,

we pointed out the existence of important theoretical lacunae, since

Coase never proves the efficient outcome of the bargaining process

but simply asserts it. Last, we questioned the underlying premise of

Coase’s theorem, i.e., the separation of the issues of efficiency and

distribution, arguing that this is not possible since changes in the lat-

ter affect the former both logically and empirically.

Regarding his economic analysis of law, we have argued that

Coase envisioned an “as if market” approach in the delimitation

of (legally enacted) rights over externalities, which is inconsistent

with and contradicts the very nature of institutionalized rights over

property, because it violates the de jure basis of these rights, as well as

their private nature. Coase’s economic analysis of law is riddled with

a constant and pervasive tension between his wish, on the one hand,

to define everything in terms of individual property rights, while,

on the other, making no individual property (legally) sacrosanct,

as its legal basis should be sacrificed to superior output (principle

of efficiency).

Turning to a more radical critique we argued that property rights

must be conceptualized within their proper social and historical con-

text. This means that an alternative theory must fully and consciously

incorporate the social and historical from the outset. Individuals do

not act in a social vacuum, but in a context of historically specific

social relations and structured social positions. In such a framework

the issue of power relations and social conflict forms an internal part

of the analysis. The social and the systemic are genuinely taken as the

starting point in the form of social relations, structures, stratifications

and classes involving power and conflict.

Meramveliotakis:

Bakogianni, 38

71410 Heraclion, Crete

Greece

gmeramv@staff.teicrete.gr

G4595.indd 63 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

64 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

Milonakis:

Karditsas 54-6

K. Halandri

15231, Athens, Greece

d.milonakis@uoc.gr

REFERENCES

Bartlett, Randall. 1989. Economics and Power: An Inquiry into Human Relations. Cam-

bridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Calabresi, Guido. 1968. “Transaction Costs, Resource Allocation and Liability Rules:

A Comment.” Journal of Law and Economics, 11:1, 67–73.

Callinicos Alex. 2004. Making History: Agency, Structure, and Change in Social Theory.

Second edition. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill.

Carey, Henry. 1868. The Harmony of Interests: Agricultural, Manufacturing and Commercial.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: Industrial Publisher.

Coase, Ronald. 1937. “The Nature of the Firm.” Economica, 4 (November), 386–405.

Reprinted in (and cited from) Coase, 1988a, 33–55.

———. 1960. “The Problem of Social Cost.” Journal of Law and Economics, 3:1, 1–44.

Reprinted in (and cited from) Coase, 1988a, 95–156.

———. 1977. “Economics and Contiguous Disciplines.” In Mark Perlman, ed., The

Organization and Retrieval of Economic Knoweledge. London: Macmillan. Reprinted

in (and cited from) Coase, 1994, 34–46.

———. 1988a. The Firm, the Market and the Law. Chicago, Illinois/London: University

of Chicago Press.

———. 1988b. “The Firm, the Market and the Law.” Pp. 1–31 in Coase, 1988a.

———. 1988c. “Notes on the Problem of Social Cost.” Pp. 157–185 in Coase, 1988a.

———. 1994. Essays on Economics and Economists. Chicago, Illinois/London: University

of Chicago Press.

Cooter, Robert. 1982. “The Cost of Coase.” Journal of Legal Studies, 11:1, 1–33.

———. 1987. “The Coase Theorem.” Pp. 64–70 in John Eatwell, Murray Milgate

and Peter Newman, eds., The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. London:

Palgrave.

Donohue, John. 1989. “Diverting the Coasean River: Incentive Schemes to Reduce

Unemployment Spells.” Yale Law Journal, 99:3, 549–609.

Duxbury, Neil. 1988. “Ronald’s Way.” Pp. 185–192 in Steven Medemia, ed., Coasean

Economics: Law and Economics and the New Institutional Economics. Boston, Mas-

sachusetts: Kluwer Academic.

Ellickson, Robert. 1986. “Of Coase and Cattle: Dispute Resolution Among Neighbors

in Shasta County.” Stanford Law Review, 38:3, 623–687.

Elster, Jon. 1982. “Marxism, Functionalism and Game Theory: The Case for Meth-

odological Individualism.” Theory and Society, 11:4, 453–482.

Farrel, Joseph. 1987. “Information and the Coase Theorem.” Journal of Economic

Perspectives, 1:2, 113–129.

G4595.indd 64 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

COASEAN PROPERTY RIGHTS 65

Fine, Ben, and Dimitris Milonakis. 2009. From Economics Imperialism to Freakonomics:

The Shifting Boundaries Between Economics and Other Social Sciences. London/New

York: Routledge.

Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The Constitution of Society: Outline of the Theory of Structuration.

Cambridge, England: Polity Press.

Hicks, John. 1939. “The Foundations of Welfare Economics.” Economic Journal, 49:196,

696–712.

Hodgson, Geoffrey. 2004. The Evolution of Institutional Economics: Agency, Structure and

Darwinism in American Institutionalism. London: Routledge.

Hoffman, Elizabeth, and Matthew Spitzer. 1982. “The Coase Theorem: Some Experi-

mental Tests.” Journal of Law and Economics, 25:1, 73–98.

Kaldor, Nicholas. 1939. “Welfare Propositions of Economics and Interpersonal Com-

parisons of Utility.” Economic Journal, 49:195, 549–552.

Knight, Jack. 1992. Institutions and Social Conflict. Cambridge, England: Cambridge

University Press.

Marx, Karl. 1904 (1858). A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Chicago,

Illinois: Charles H. Kerr.

———. 1993 (1857). Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy. Lon-

don: Penguin.

———. 2001 (1847). The Poverty of Philosophy. Chicago, Illinois: Elibron.

Medema, Steven, ed. 1998. Coasean Economics: Law and Economics and the New Institu-

tional Economics. Norwell, Massachusetts: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Medema, Steven, and Richard Zerbe. 2000. “The Coase Theorem.” Pp. 836–892 in

Boudewijn Bouckaert and Gerrit De Geest, eds., The Encyclopedia of Law and

Economics. Vol. 1. Aldershot, England: Edward Elgar.

Meramveliotakis, Giorgos, and Dimitris Milonakis. 2010. “Surveying the Transaction

Cost Foundation of New Institutional Economics: A Critical Inquiry.” Journal of

Economic Issues, XLIV:4, 1045–1071.

North, Douglass. 1981. Structure and Change in Economic History. New York/

London: W. W. Norton.

Pigou, Arthur. 1962 (1932). The Economics of Welfare. London: Macmillan.

Regan, Donald. 1972. “The Problem of Social Cost Revisited.” Journal of Law and

Economics, 15:2, 427–437.

Samuelson, Paul. 1967. “The Monopolistic Competition Revolution.” Pp. 18–51 in

Robert Kuenne, ed., Monopolistic Competition Theory: Studies in Impact; Essays in

Honor of Edward H. Chamberlin. New York: Wiley. Reprinted in Merton, ed., The

Collected Scientific Papers of Paul A. Samuelson. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT

Press, 1972.

Sayer, Derek. 1987. The Violence of Abstraction: The Analytic Foundations of Historical

Materialism. Oxford, England: Basil Blackwell.

Simpson, Brian. 1996. “‘Coase v. Pigou’ Reexamined.” The Journal of Legal Studies,

25:1, 53–97.

Stiglitz, Joseph. 1994. Whither Socialism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Usher, Dan. 1998. “The Coase Theorem is Tautological, Incoherent or Wrong.”

Economic Letters, 61:1, 3–11.

G4595.indd 65 12/6/2017 9:30:59 AM

66 SCIENCE & SOCIETY

Veljanovski, Centro. 1982. “The Coase Theorems and the Economic Theory of Mar-