Professional Documents

Culture Documents

TopicsinEarlyChildhoodSpecialEducation 2014 Green 249 59

TopicsinEarlyChildhoodSpecialEducation 2014 Green 249 59

Uploaded by

Amani Adam DawoodOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

TopicsinEarlyChildhoodSpecialEducation 2014 Green 249 59

TopicsinEarlyChildhoodSpecialEducation 2014 Green 249 59

Uploaded by

Amani Adam DawoodCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/283534949

Growth in language and literacy skills among children with disabilities in

inclusive early reading first classrooms

Article in Topics in Early Childhood Special Education · January 2013

DOI: 10.1177/0271121413477498

CITATIONS READS

18 607

3 authors, including:

Katherine Green Nicole Patton Terry

University of West Georgia Georgia State University

22 PUBLICATIONS 63 CITATIONS 31 PUBLICATIONS 364 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE

Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects:

Parent-Child Interactive Early Communication Study. View project

iCARE: Instruction of Children At Risk or with Exceptionalities. A Head Start Partnership. View project

All content following this page was uploaded by Katherine Green on 07 November 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

477498

in Early Childhood Special EducationGreen et al.

© Hammill Institute on Disabilities 2011

Reprints and permission: http://www.

TEC33410.1177/0271121413477498Topics

sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Article

Topics in Early Childhood Special Education

Progress in Language and Literacy Skills

2014, Vol. 33(4) 249–259

© Hammill Institute on Disabilities 2013

Reprints and permissions:

Among Children With Disabilities in sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/0271121413477498

tecse.sagepub.com

Inclusive Early Reading First Classrooms

Katherine B. Green, MEd1, Nicole Patton Terry, PhD1,

and Peggy A. Gallagher, PhD1

Abstract

Quality literacy instruction in preschool can be critical to the future academic success for all children, but may be even

more so for children with disabilities. The purpose of this study was to examine progress in emergent literacy skills of

young children with disabilities, compared with their typical peers, in an inclusive preschool setting. Participants in this study

included 77 prekindergarteners with disabilities and 77 children with no identified disabilities who were matched based on

age, teacher, and school. Children were enrolled in inclusive Early Reading First prekindergarten classrooms. Results suggest

that although children with disabilities made significant gains mirroring the progress of their typical peers, as a group, they

did not catch up to the achievement of their typical peers. Children with disabilities showed the greatest progress in Print

Awareness and Recognizing Uppercase Letters. Implications for future instruction and research are outlined.

Keywords

emergent literacy, inclusion, disabilities, preschool

Learning to read is one of the most important skills for chil- Fortunately, researchers have found that emergent literacy

dren in our society. Preschoolers who exhibit well-developed skills can be taught to and learned by young children with

emergent literacy skills typically have better success in disabilities (e.g., Adams, Foorman, Lundberg, & Beeler,

all academic areas from elementary through high school 1998; Blachman, Ball, Black, & Tangle, 2000; Wagner,

(Lonigan, Burgess, & Anthony, 2009). Conversely, Torgesen, & Rashotte, 1994). Furthermore, additional stud-

researchers have found that children who lack appropriate ies show that preschool children with disabilities demon-

early literacy skills are more likely to have difficulty acquir- strate growth in emergent literacy skills when they are given

ing reading skills, read less, and receive less practice a structured literacy-rich environment (Katims, 1994). The

than proficient readers (Allington, 1984; Snow, Burns, & current investigation focuses on the language and literacy

Griffin, 1998). Subsequently, children with difficulties in outcomes of children with disabilities in such an environ-

emergent literacy skills may fall even further behind their ment: Early Reading First (ERF) classrooms.

peers as they progress in school (Allington, 1984; Snow et As part of the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001, ERF

al., 1998). While receiving quality literacy instruction in programs focus on enhancing children’s early language and

preschool is critical to the future academic success for all literacy skills through curriculum adoption and/or enhance-

children, it is especially so for children who enter school ment, classroom modification, and teacher professional

developmentally behind their peers. With estimations that development (e.g., coaching, workshops, and classroom

more than one in three children experience difficulty learn- support). The purpose of ERF was to prevent later reading

ing to read (Adams, 1990; Shaywitz, Escobar, Shaywitz, difficulties by providing young children, particularly

Fletcher, & Makuch, 1992), it is important that emergent from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, with high-quality

literacy skills be specifically taught in the preschool

classroom. 1

Georgia State University, Atlanta, USA

Many children with disabilities struggle to acquire emer-

gent literacy skills that are associated with later literacy Corresponding Author:

Katherine B. Green, Department of Educational Psychology and Special

achievement such as oral vocabulary, phonological aware- Education, Georgia State University, P.O. Box 3979, Atlanta, GA 30302-

ness, and print and alphabet knowledge (Sulzby & Teale, 3979, USA.

1991; Teale & Sulzby, 1986; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998). Email: kgreen16@gsu.edu

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

250 Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 33(4)

language and literacy-rich environments to prepare them and systematic instruction in homogeneous small groups

for school success. (Gersten et al., 2008; Gunn, Biglan, Smolkowski, & Ary,

2000; Jenkins, Peyton, Sanders, & Vadasy, 2004; Vadasy,

Sanders, & Peyton, 2005; Vaughn et al., 2006), as well as

Critical Emergent Language and progress monitoring of emergent literacy skills at least one

Literacy Skills and Instruction time per month (Mathes et al., 2005; McMaster, Fuchs,

Emergent literacy skills are predictive of later reading Fuchs, & Compton, 2005; Vaughn et al., 2006). Students

success and therefore should be emphasized in preschool who do not make adequate progress in Tiers 1 or 2 may

instruction (Chatterji, 2006; National Early Literacy Panel require more intensive, individualized daily instruction, as

[NELP], 2008; Scarborough, 2001). In a recent meta- found in Tier 3 interventions (Gillon, 2000; McMaster et al.,

analysis of studies on emergent literacy skills and instruc- 2005). The movement between tiers is based on academic

tion, NELP (2008) found that the skills with the strongest progress throughout the school year. The children receiving

predictive relationship with later literacy outcomes included instruction in Tiers 2 or 3 may or may not have an individu-

alphabet knowledge (letter names and sounds), phonologi- alized education plan (IEP; Greenwood et al., 2011).

cal awareness (ability to think about and manipulate sounds High-quality emergent literacy instruction is of impor-

in words), print concepts (knowledge of forms and use of tance to young children in the prevention of later eligibility

print), and oral language (ability to use and comprehend of special education, as little or no exposure to early literacy

language in communicative contexts). Moreover, the panel experiences places children at risk of later challenges in lan-

found that specific instructional strategies and approaches guage and literacy (Chard & Kameenui, 2000; Shonkoff &

can promote the development of these skills, including Phillips, 2000; Zill & Resnick, 2006). Furthermore, chil-

code-focused interventions (designed to teach skills related dren who attend preschool are placed at less risk of later

to understanding the alphabetic principle) and language- special education identification (Belfield, 2005), as well as

enhancement interventions (designed to improve expres- for learning disabilities (Conyers, Reynolds, & Ou, 2003)

sive and receptive oral language skills) in preschool and than those who do not attend preschool. Yet, with the

kindergarten programs. Specifically, phonological aware- expansion of inclusive placements within early childhood

ness instruction had the most significant and largest effect settings (Odom et al., 2004), it is important to examine how

size (0.82) of all code-focused interventions to later literacy these placements effect the academic skills of children with

skills, supporting the importance of phonological aware- disabilities and their typically developing peers.

ness in the early childhood setting. Overall, the findings

from the NELP report highlight not only the critical early

language and literacy skills that are likely to support future Early Literacy Achievement Among

reading success but also the wide variety of instructional Preschoolers With Disabilities in

approaches that can be taken during the preschool years to Inclusive Settings

promote growth in young children with and without dis-

abilities. Many children with a variety of disabilities may experience

Instructional strategies for early childhood classrooms challenges with learning emergent literacy skills. Children

can be discussed in terms of Response to Intervention with language impairments, particularly those with delays

(RTI). RTI is a multitiered prevention pyramid model in vocabulary, comprehension, syntax, and phonological

designed to detect, prevent, and address academic chal- awareness, are more likely to experience difficulty with

lenges of children. The primary or universal tier of RTI sup- conventional (e.g., decoding, oral reading fluency, reading

ports the academic needs of all children in the classroom. comprehension, writing, and spelling) and emergent liter-

Instruction in the universal tier may also be referred to as acy skills (e.g., oral language, print and letter knowledge,

evidence-based reading instruction (Vaughn & Fuchs, and phonological processing; Bishop & Adams, 1990;

2006) or high-quality reading instruction (Division for Catts, 1997; NELP, 2008; Scarborough, 1990; Wagner &

Learning Disabilities, 2007). In early primary years, univer- Torgesen, 1987; Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998). Children

sal strategies may include whole-class instruction with the with cognitive delays (e.g., Down syndrome), autism, and

critical emergent literacy skills (i.e., phonological aware- other developmental disabilities often have language

ness, alphabet knowledge, print concepts, and oral lan- impairments that are characteristic of their disability. For

guage), as well as differentiated early literacy instruction instance, children with autism may have difficulty with

such as varying the time, content, level of support, and scaf- spontaneous language, pragmatics, delayed grammar usage,

folding (Connor et al., 2009). Within the RTI model, Tier 2 oral language skills, and vocabulary development skills

interventions are designed for students who exhibit chal- (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; V. Smith, Mirenda,

lenges or weak progress with regular classroom instruction. & Zaidman-Zait, 2007; Wilkinson, 1998). Children with

Evidence-based Tier 2 strategies include intense, explicit, Down syndrome typically have stronger expressive

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

Green et al. 251

language skills than receptive skills, and have particular emergent literacy progress in children with disabilities and

challenges with phonology (e.g., phonological processes typically developing peers within inclusive settings. This

and poorer speech intelligibility) and syntax (e.g., delays in study will add to the literature base by examining progress

morphology and complex utterances; Martin, Klusek, in emergent literacy skills for all children in inclusive pre-

Estigarribia, & Roberts, 2009). school classrooms and to help determine whether a high-

Inclusion within early childhood settings is a primary quality language and literacy-based classroom can assist in

placement for many children with a variety of disabilities reducing the achievement gap between children with dis-

(Odom, Buysse, & Soukakou, 2011). Inclusion not only abilities and their typically developing peers. The purpose

refers to the placement of children with disabilities in the of this study was to examine progress in emergent literacy

same class as typically developing peers but also includes skills of young children with disabilities, compared with

the socialization and shared learning environments with typ- their typically developing peers, in an inclusive ERF pre-

ically developing peers (Division for Early Childhood/ school setting. The following research questions were posed:

National Association for the Education of Young Children,

2009). Within an inclusive environment, children with dis- Research Question 1: How much progress did children

abilities should be provided with the supports and services with disabilities experience in oral vocabulary, pho-

as necessary (Rafferty, Piscitelli, & Boettcher, 2003; Winter, nological awareness, and alphabet and print knowl-

1999), as well as equal opportunities within the same class- edge during the prekindergarten year, compared with

room (Odom et al., 1996; Peck, Odom, & Bricker, 1993). their typically developing peers?

Several studies have shown that children with and with- Research Question 2: Did the achievement gap

out disabilities benefit socially in inclusive settings (e.g., between children with disabilities and typical peers

Buysse & Bailey, 1993; Buysse, Goldman, & Skinner, narrow in oral vocabulary, phonological awareness,

2002; Cross, Traub, Hutter-Pishgahi, & Shelton, 2004; and alphabet and print knowledge over the course of

Gallagher & Lambert, 2006; Guralnick & Groom, 1988; the prekindergarten year?

Jenkins, Speltz, & Odom, 1985). However, fewer studies

have explored how children with disabilities progress in

specific emergent literacy skills within inclusive preschool Method

settings. In a study examining language development and Participants

social competence in inclusive and segregated settings of

children with disabilities, Rafferty et al. (2003) found no The sample was pooled from a larger evaluation database of

differential impact on the effect sizes on language and 652 children who participated in ERF classrooms. The data

social competences between inclusive and segregated set- were collected over 2 academic year periods. Of these 652

tings for preschoolers with mild to moderate disabilities. children, 77 had IEPs, spoke English as their first language

Holahan and Costenbader (2000) found that preschoolers (M age = 50 months, SD = 6.14), and exhibited adequate

functioning at a higher level of social and emotional skills speech and language skills to perform the assessment tasks

performed better on developmental outcomes in inclusive without adaptations. This is the population we chose to

settings as opposed to segregated settings. In an examina- study. These 77 children with disabilities were matched to

tion of changes in language development for preschoolers 77 children with no identified disabilities who also spoke

with autism and typically developing peers in segregated English as their first language (M age = 51 months, SD =

and integrated settings, Harris, Handleman, Kristoff, Bass, 5.1). The sample consisted of 37% female and 63% male

and Gordon (1990) found that all children, typically devel- participants. All children in the sample attended the ERF

oping and those with autism, benefitted from a quality lan- prekindergarten program 1 entire school year. Children

guage enriched inclusive preschool in the area of language were matched based on the school or child care site they

development. The instructional approaches consisted of attended, then the classroom, next their age in months, and

whole group, small group, and individualized instruction in finally their gender. There were no instances where matches

the inclusive environment. were not able to be narrowed using this hierarchy.

All children were enrolled in inclusive prekindergarten

classrooms that were participating in ERF. The 38 class-

Purpose of Study rooms were located in public elementary schools and pri-

One reason many children with disabilities may be placed vate child care sites in a large, urban area in the southeastern

in inclusive preschool classrooms is to improve their aca- United States. Inclusionary criteria for classrooms included

demic outcomes. Therefore, it is important to not only an ELLCO Pre-K (M. W. Smith & Dickinson, 2002)

examine whether children with disabilities show significant Literacy Environment Checklist average score of “basic”

progress in social skills but also to examine early academic (M = 3) for the Language and Literacy Environment items.

areas, as well. There is a paucity of research regarding Because these participating sites received ERF funding, all

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

252 Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 33(4)

sites served children who lived in poverty, as indicated by Procedures

the percentage of children participating in federal free and

reduced lunch programs. Importantly, all of the children in this study attended ERF

The children with disabilities were receiving special classrooms during their prekindergarten year. Classroom

education services for a variety of disabilities commonly teachers who participated in ERF were provided with pro-

diagnosed by the preschool years, including developmen- fessional development to enhance children’s language, lit-

tal delays, autism, pervasive developmental disorders–not eracy, and cognitive skills. The teachers in this ERF

otherwise specified, speech and language impairments, program participated in approximately 50 hr of profes-

cognitive impairments, and Down syndrome. Although sional development on teaching language and literacy skills

each disability presents specific challenges, children in in the preschool classroom. They also had coaches and

this sample were all functioning at social, cognitive, weekly on-site support in their school.

behavioral, and linguistic levels to the extent their IEP The PPVT-3 was given to all children in the fall and

teams had recommended they participate in language and spring of their prekindergarten school year, per regulations

literacy instruction in the general education classroom of the ERF program. In addition, although not required,

with typical peers. In addition, only data from children some participating classrooms used the PALS-PreK to cap-

who were able to complete the tasks according to stan- ture additional information regarding the children’s early

dardized administrative format were included in the language and literacy skills. When this information was

analyses. available, it was used in the analyses for this study.

Assessments were administered at the child’s school in

standardized format according to test manuals by trained

Measures examiners. Data were analyzed to determine progress in the

Oral receptive vocabulary. Vocabulary was assessed using language and literacy skills of both groups of children.

the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition

(PPVT-3; Dunn & Dunn, 1997). The PPVT-3 is a nation-

ally normed assessment and is appropriate for ages 2 Results

through adulthood. On this assessment, children are pre- To answer the research questions, two types of primary

sented with an array of four pictures of common objects analyses were performed. First, pre–post repeated measures

and actions. Children are asked to identify a target picture ANOVAs were conducted to examine progress within the

by pointing (e.g., “point to a faucet”). Internal reliability groups and differences between the two groups on the

on the PPVT-3 is .92 to .98 (median = .95; PPVT-3; Dunn PPVT-3 and PALS-PreK, as well as any interaction effects.

& Dunn, 1997). The PPVT-3 and each of the PALS-PreK subtests were

analyzed separately. Gain scores were computed on all

Emergent literacy achievement. A variety of early literacy measures to examine how scores changed over the prekin-

skills were measured with the Phonological Awareness Lit- dergarten year and to determine whether the achievement

eracy Screening Prekindergarten (PALS-PreK; Invernizzi, gap between children with disabilities and typically devel-

Sullivan, Meier, & Swank, 2004). This battery of assess- oping peers was changed between the groups (see Table 1).

ments was chosen because it can be administered individu-

ally, and because many of the emergent literacy skills can

be assessed quickly and reliably. This study included the Progress in Early Language

following subtests of the PALS-PreK: (a) Alphabet and Literacy Skills

Knowledge—Children are asked to name uppercase let- Between-group results. Using repeated measures ANOVAs,

ters, children who name 16 or more correctly are asked to the data were analyzed to determine the differences in prog-

name the lowercase letters, and children who name nine or ress on language and literacy skills from fall to spring

more lowercase letters are asked to say the sounds that the between the typically developing peers and children with

letters make; (b) Beginning Sound Awareness—Children disabilities. As expected, all children exhibited progress

are presented with pictures and are asked to produce the during the prekindergarten year. Furthermore, typically

first sound for the words that begin with /s/, /m/, and /b/; developing children performed significantly better than

(c) Print and Word Awareness—Children are asked to children with disabilities on the PPVT-3, η2 = .177,

identify various text components while the examiner reads F(1, 142) = 30.483, p < .001, as well as on all subtests of the

a nursery rhyme printed in a book; and (d) Rhyme Awareness— PALS-PreK: Uppercase Letter Recognition, η2 = .060,

Children are presented with four pictures and are asked to F(1, 70) = 4.47, p < .05, Print Awareness, η2 = .171,

identify the two pictures that rhyme. Reliability ranges F(1, 84) = 17.269, p < .001, Beginning Sounds, η2 = .086,

from .75 to .93 for the four subtests (Invernizzi et al., F(1, 86) = 8.092, p < .05, and Rhyme Awareness, η2 = .167,

2004). F(1, 80) = 16.089, p < .001.

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

Green et al. 253

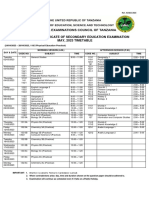

Table 1. Mean Group Performance and Gain Scores.

Children with disabilities N Fall scores (SD) Spring scores (SD) Percentage gained

PPVT-3 77 88.60 (21.12) 90.53 (17.9) 2.18

Uppercase letter recognition 36 13.69 (10.83) 18.36 (9.53) 34.11

Beginning sounds 44 4.09 (4.08) 5.20 (4.32) 27.14

Print awareness 43 3.79 (3.11) 5.95 (3.27) 56.99

Rhyme awareness 41 4.85 (3.04) 6.15 (3.40) 26.80

Typical peers

PPVT-3 77 104.17 (16.28) 105.64 (15.52) 1.41

Uppercase letter recognition 36 17.86 (8.69) 22.56 (5.79) 26.32

Beginning sounds 44 5.68 (3.72) 7.91 (3.25) 39.26

Print awareness 43 6.37 (2.74) 8.02 (1.86) 25.90

Rhyme awareness 41 6.71 (2.70) 8.63 (1.85) 28.61

Note. PPVT-3 = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition. Scores on the PPVT-3 are in standard scores and PALS-PreK are in raw scores. Percentage

gained is the percent the students improved on the measure from fall to spring.

Figure 1. Mean growth in standard scores on the PPVT-3 from fall to spring by group.

Note. PPVT-3 = Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test–Third Edition.

Within-group results. The data were also analyzed to examine Achievement gap between children with disabilities and typically

how each group progressed on the language and literacy developing peers. Given that children from both groups

tasks from fall to spring. On the PPVT-3, neither group showed significant progress on specific language and liter-

showed significant progress in standard scores from fall to acy tasks from fall to spring, we next computed gain scores

spring. However, unlike the PPVT-3, significant within- to see how the children’s skills changed over 1 academic

group differences were observed for both groups of chil- school year, and whether the achievement gap between the

dren on several subtests of the PALS-PreK. All children groups changed as well. There were no interactive effects;

performed significantly better from fall to spring on Upper- thus, there were no significant achievement gap changes for

case Letter Recognition, η2 = .387, F(1, 70) = 44.278, any measure for either group nor were there any signifi-

p < .001, Print Awareness, η2 = .456, F(1, 84) = 70.312, cant effects on within-subjects. On the PPVT-3, children in

p < .001, Beginning Sounds, η2 = .232, F(1, 86) = 25.938, both groups gained slightly less than two standard score

p < .001, and Rhyme Awareness, η2 = .262, F(1, 80) = 28.366, points by the spring (see Figure 1). Although significant

p < .001. Although both groups showed progress on all within-group differences were not found in mean standard

assessments, the effect sizes between pre- and post-assessments scores, there was a slight change from fall to spring narrow-

were considered small (Cohen, 1988). ing the performance gap between the groups by .46 points.

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

254 Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 33(4)

Figure 2. Mean Growth in PALS-PreK Print and Word Awareness subtest from fall to spring.

Note. PALS-PreK = Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening Prekindergarten.

Figure 3. Mean growth in PALS-PreK uppercase alphabet recognition subtest from fall to spring.

Note. PALS-PreK = Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening Prekindergarten.

Interestingly, a different pattern was found on the Discussion

PALS-PreK. Although children in both groups made prog- This study had two goals. First, we examined progress in

ress from fall to spring on each subtest, the performance emergent literacy skills in children with disabilities in

gap between typically developing children and children inclusive language and literacy-enriched prekindergarten

with disabilities narrowed on the Print Awareness subtest, classrooms as compared with their typically developing

specifically by .51 raw score points (see Figure 2). The classmates. Second, we explored whether the achievement

gap widened on the Uppercase Letter Recognition, Rhyme gap was narrowed between the children with disabilities

Awareness, and Beginning Sounds subtests by .03, .62, and children without identified disabilities. Overall, the

and 1.12 raw score points, respectively (see Table 1; see results suggested that children with disabilities made sig-

Figures 3–5). nificant progress in emergent literacy skills, mirroring the

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

Green et al. 255

Figure 4. Mean growth in PALS-PreK Rhyme Awareness subtest from fall to spring.

Note. PALS-PreK = Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening Prekindergarten.

Figure 5. Mean growth in PALS-PreK beginning sounds subtest from fall to spring.

Note. PALS-PreK = Phonological Awareness Literacy Screening Prekindergarten.

gains of their typically developing peers. Yet as a group, higher posttest scores than their matched peers. However,

the children with disabilities did not catch up with their as a group, the children with disabilities started further behind,

typically developing peers on any language and literacy task. and the progress patterns did not allow them to catch up to

Importantly, the typically developing peers and the group the achievement of their typically developing peers.

of children with disabilities varied in their individual Not surprisingly, typically developing children outper-

scores. Some participants with disabilities had higher formed the children with disabilities throughout the prekin-

pretest scores than did the typically developing peers. dergarten year. However, children with disabilities made

Furthermore, some children with disabilities exhibited similar gains in receptive vocabulary as the typically

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

256 Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 33(4)

developing peers. Given the nature of standard scores, it is classrooms. The NELP (2008) report stated that alphabet

difficult to show progress on this measure over 1 school knowledge, phonological awareness, print concepts, and

year. Nevertheless, it is encouraging to find that children oral language have a strong predictive relationship with

with disabilities not only maintained their vocabulary skills later literacy outcomes. As children with disabilities experi-

but also showed some progress over the prekindergarten ence difficulties when learning these emergent literacy

year while participating in whole-classroom language and skills (Sulzby & Teale, 1991; Teale & Sulzby, 1986;

literacy instruction. Whitehurst & Lonigan, 1998), and given the increase of

On the PALS-PreK, children with disabilities made the inclusive environments (Odom et al., 2011), this study adds

least amount of progress on the phonological awareness to the research on academic benefits of children with dis-

tasks, as opposed to their typically developing peers. The abilities in inclusive literacy-rich environments.

children with disabilities never caught up with typical peers Although positive, the results should be viewed with

on these tasks. Children with disabilities experienced the caution. There are limitations to this study. Because this

most amount of gain with the print awareness and recogniz- study involved analyses from a much larger data set, infor-

ing uppercase letters tasks. For the typically developing mation was missing regarding the exact nature of special

peers, the least amount of gain was in print awareness; how- education services the children with disabilities received,

ever, even on this task, the gains made by children with the specific special education eligibility category of each

disabilities did not allow them to surpass or match the post- individual child and information on individual ethnicities,

test score of their typical peers. and socioeconomic levels. This is a limitation that limits the

With regard to the achievement gap between the children interpretation and generalization of the results. Another

with disabilities at the beginning of the prekindergarten limitation is that not all of the children in this study were

year, there were no significant changes for any of the tasks, given the PALS-PreK assessment, as noted in Table 1.

as indicated by the lack of interaction effects within the Information regarding the missing pieces of descriptive

analysis of groups and measures. This finding was qualified data would be beneficial for future research. Nevertheless,

by an examination of the means. Children with disabilities this study is an important step in characterizing how chil-

progressed from the instruction they received, but only nar- dren with disabilities fare in language and literacy inclusive

rowed the achievement gap in oral expressive language and classrooms. It is also important to acknowledge that the

print awareness, and the gap actually widened on the pho- children in this study were participating in ERF classrooms,

nological awareness measures. where they were exposed to high-quality language and lit-

These findings can be interpreted as support that chil- eracy instruction and resources from trained teachers and

dren with disabilities may experience significant gains in coaches who supported that instruction. Certainly, this is

orthographic skills (e.g., alphabet recognition and print not the case in all prekindergarten classrooms. It is not clear

concepts) in inclusive settings. Meanwhile, phonological whether such positive results would have been found in

awareness instruction may require more explicit instruc- classrooms without these kinds of supports in place.

tion. Certainly, there is empirical evidence that suggests Implications for the classroom from this study include

that young children who struggle with phonological aware- the need to explicitly address phonological awareness

ness can benefit from explicit, small group, intensive skills to children with disabilities. These findings may be

instruction during the preschool years (Elbaum, Vaughn, interpreted in terms of RTI. For example, the results indi-

Hughes, & Moody, 1999; Phillips, Clancy-Menchetti, & cated that children with disabilities benefited from partici-

Lonigan, 2008; Pullen & Justice, 2003). Explicit instruction pating in high-quality language and literacy instruction in

includes the teaching of the most efficient and effective inclusive environments, such as would be seen in a Tier 1 or

method possible (Carnine, Silbert, Kame’enui, & Tarver, universal instruction. Yet, some students, such as the lower

2004). Within this instructional approach, the teacher leads achieving students may require additional instruction in

the instruction, determines the instructional goals and pace, phonological awareness skills possibly in small group set-

chooses the appropriate materials, and provides immediate tings, such as a Tier 2 intervention. It is possible that had the

corrective feedback to the student. Tasks may be broken lower achieving students received explicit, small group, or

down into smaller skills and are sequenced to allow for stu- individualized instruction commonly found in Tiers 2 or 3

dent mastery of prerequisite skills before moving on to of RTI, the achievement gap between typically developing

more challenging skills (Joyce, Weil, & Calhoon, 2000). peers and children with disabilities may have narrowed.

As with other research on this topic (e.g., Cross et al., Examples of current RTI frameworks and resources for pre-

2004; Harris et al., 1990; Holahan & Costenbader, 2000; kindergarten include Center for Response to Intervention

Rafferty et al., 2003), the findings from this study suggest in Early Childhood (CRTIEC, 2012; www.crtiec.org/),

that children with disabilities benefit in language and emer- Recognition and Response (Coleman, Buysse, & Neitzel,

gent literacy skills from participating in high-quality lan- 2006), and Exemplary Model of Early Reading Growth and

guage and literacy instruction in inclusive prekindergarten Excellence (EMERGE; Gettinger & Stoiber, 2008).

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

Green et al. 257

It is also important to note that the skills the children Funding

with disabilities had the most challenge with auditory-based

and more abstract concepts (e.g., beginning sounds and The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support

rhyming awareness). The skills they performed best in were for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This

orthographic and more concrete concepts (e.g., print and study was supported in part by the Developing Readers Early and

word awareness and letter recognition). Being aware of this Mightily (DREAM) and Reinforce, Educate, and Develop Early

information, teachers may need to have a greater instruc- Readers Successfully (READERS). Early Reading First Program

tional focus on teaching phoneme and rhyming awareness grants were awarded to the United Way of Greater Atlanta (Grant

tasks. Implications for future research areas include the Nos. S359BO50040 and S359BO60041).

increased need to study emergent literacy skills in children

with disabilities, particularly in inclusive environments, and References

examine what types of Tier 2 and 3 interventions might Adams, M. J. (1990). Learning to read: Thinking and learning

affect the academic gap for children with disabilities. about print. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

In sum, the findings in this study guide us toward future Adams, M. J., Foorman, B. R., Lundberg, I., & Beeler, T. (1998).

research that examines the academic implications of inclusive The elusive phoneme: Why phonemic awareness is so impor-

environments for young children with disabilities. Children tant and how to help children develop it. American Educator,

with disabilities are increasingly placed in inclusive prekin- 22, 18–29.

dergarten environments. Furthermore, many researchers have Allington, R. L. (1984). Content, coverage, and contextual reading

suggested that inclusion is socially beneficial for children in reading groups. Journal of Reading Behavior, 16, 85–86.

with and without disabilities (Buysse & Bailey, 1993; Buysse American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and statis-

et al., 2002; Cross et al., 2004; Gallagher & Lambert, 2006; tical manual of mental disorders (4th ed., text rev.). Washing-

Guralnick & Groom, 1988; Jenkins et al., 1985). However, ton, DC: Author.

there is a paucity of literature on the academic progress of Belfield, C. R. (2005). The cost savings to special education

children with disabilities in inclusive environments. This from preschooling in Pennsylvania. Harrisburg: Pennsylva-

investigation adds to the literature on academic skills of typi- nia Department of Education, Pennsylvania Build Initiative.

cal children and children with disabilities on inclusive literacy- Retrieved from http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt?

rich environments. This study was an attempt to answer open=18&;objID=381892&mode=2

questions about how all prekindergarten children progress Bishop, D. V. M., & Adams, C. (1990). A prospective study of

when participating in literacy-enriched environments, and the relationship between specific language impairment, pho-

indeed they did show progress. However, their growth is not nological disorders and reading retardation. Journal of Child

without complexity, as some skills may be best approached in Psychology and Psychiatry, 31, 1027–1050.

other instructional contexts, specifically those related to pho- Blachman, B. A., Ball, E. W., Black, R., & Tangle, D. M. (2000).

nological awareness instruction, as the achievement gap Road to the code: A phonological awareness program for

between children with and without disabilities widened for young children. Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brooks.

these skills. Overall, we view these findings as supportive of Buysse, V., & Bailey, D. B. (1993). Behavioral and developmental

inclusive language and literacy instruction during the prekin- outcomes in young children with disabilities in integrated and

dergarten year, and as a positive step toward understanding segregated settings: A review of comparative studies. Journal

the conditions under which children with disabilities can ben- of Special Education, 26, 434–461.

efit academically from participating in these classrooms. Buysse, V., Goldman, B. D., & Skinner, M. (2002). Setting effects

on friendship formation among young children with and with-

Acknowledgments out disabilities. Exceptional Children, 68, 503–517.

We would like to thank the Smart Start/Education staff at United Carnine, D. W., Silbert, J., Kame’enui, E. J., & Tarver, S. G.

Way Greater Atlanta, particularly Katrina D. Mitchell, for their (2004). Direct instruction reading (4th ed.). Upper Saddle

assistance with this project. We especially thank the children and River, NJ: Pearson.

families who participated in this project, without whom this Catts, H. W. (1997). The early identification of language-based

research would not have been possible. reading disabilities. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services

in Schools, 28, 86–87.

Authors’ Note Center for Response to Intervention in Early Childhood. (2012).

The opinions expressed in this article are authors’ and do not Available from http://www.crtiec.org/

represent views of the funding agencies. Chard, D. J., & Kameenui, E. J. (2000). Struggling first-grade

readers: The frequency and progress of their reading. Journal

Declaration of Conflicting Interests of Special Education, 34, 28–38.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with Chatterji, M. (2006). Reading achievement gaps, correlates, and

respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this moderators of early reading achievement: Evidence from the

article. Early Childhood Longitudinal Study (ECLS) kindergarten to

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

258 Topics in Early Childhood Special Education 33(4)

first grade sample. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, Greenwood, C. R., Bradfield, T., Kaminski, R., Linas, M., Carta, J. J.,

489–507. & Nylander, D. (2011). The response to intervention (RTI)

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sci- approach in early childhood. Focus on Exceptional Children,

ences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. 43, 1–21.

Coleman, M. R., Buysse, V., & Neitzel, J. (2006). Recognition Gunn, B., Biglan, A., Smolkowski, K., & Ary, D. (2000). The effi-

and response: An early intervening system for young children cacy of supplemental instruction in decoding skills for His-

at risk for learning disabilities (Full report). Chapel Hill: The panic and non-Hispanic students in early elementary school.

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, FPG Child Devel- Journal of Special Education, 34, 90–103.

opment Institute. Guralnick, M. J., & Groom, J. M. (1988). Peer interactions in

Connor, C. M., Piasta, S. B., Fishman, B., Glasney, S., Schatschneider, C., mainstreamed and specialized classrooms: A comparative

Crowe, E., & Morrison, F. J. (2009). Individualizing student analysis. Exceptional Children, 54, 415–425.

instruction precisely: Effects of child by instruction interac- Harris, S. L., Handleman, J. S., Kristoff, B., Bass, L., & Gordon, R.

tions on first graders’ literacy development. Child Develop- (1990). Changes in language development among autistic and

ment, 80, 77–100. peer children in segregated and integrated preschool settings.

Conyers, L. M., Reynolds, A. J., & Ou, S. (2003). The effect of Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 20, 23–31.

early childhood intervention and subsequent special education Holahan, A., & Costenbader, V. (2000). A comparison of develop-

services: Findings from the Chicago child-parent centers. Edu- mental gains for preschool children with disabilities in inclu-

cational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 25, 75–95. sive and self-contained classrooms. Topics in Early Childhood

Cross, A. G., Traub, E. K., Hutter-Pishgahi, L., & Shelton, G. Special Education, 20, 224–235.

(2004). Elements of successful inclusion for children with sig- Invernizzi, M., Sullivan, A., Meier, J., & Swank, L. (2004). Pho-

nificant disabilities. Topics in Early Childhood Special Educa- nological Awareness Literacy Screening PreK (PALS-PreK).

tion, 24, 169–183. Charlottesville: University of Virginia.

Division for Early Childhood/National Association for the Educa- Jenkins, J. R., Peyton, J. A., Sanders, E. A., & Vadasy, P. F.

tion of Young Children. (2009). Early childhood inclusion: (2004). Effects of reading decodable texts in supplemental

A joint position statement of the division for early childhood first-grade tutoring. Scientific Studies of Reading, 8, 53–85.

(DEC) and the national association for the education of young Jenkins, J. R., Speltz, M. L., & Odom, S. L. (1985). Integrating

children (NAEYC). Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina, normal and handicapped preschoolers: Effects on child devel-

FPG Child Development Institute. opment and social interaction. Exceptional Children, 52, 7–17.

Division for Learning Disabilities. (2007). Thinking about Joyce, B., Weil, M., & Calhoon, E. (2000). Models of teaching

response to intervention and learning disabilities: A teacher’s (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

guide. Arlington, VA: Author. Katims, D. S. (1994). Emergence of literacy in preschool children

Dunn, L. M., & Dunn, L. M. (1997). Peabody Picture Vocabulary with disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 17, 58–69.

Test (3rd ed.). Circle Pines, MN: American Guidance Service. Lonigan, C., Burgess, S., & Anthony, J. (2009). Development of

Elbaum, B., Vaughn, S., Hughes, M., & Moody, S. W. (1999). emergent literacy and early reading skills in preschool chil-

Grouping practices and reading outcomes for students with dren: Evidence from a latent-variable longitudinal study.

disabilities. Exceptional Children, 65, 399–415. Developmental Psychology, 36, 596–613.

Gallagher, P. A., & Lambert, R. G. (2006). Classroom quality, Martin, G. E., Klusek, J., Estigarribia, B., & Roberts, J. E. (2009).

concentration of children with special needs, and child out- Language characteristics of individuals with Down syndrome.

comes in Head Start. Exceptional Children, 73, 31–52. Topics in Language Disorders, 29, 112–132.

Gersten, R., Compton, D., Connor, C. M., Dimino, J., Santoro, L., Mathes, P. G., Denton, C., Fletcher, J., Anthony, J., Francis, D.,

Linan-Thompson, S., & Tilly, W. D. (2008). Assisting students & Schatschneider, C. (2005). The effects of theoretically

struggling with reading: Response to Intervention and multi- different instruction and student characteristics on the skills

tier intervention for reading in the primary grades. A practice of struggling readers. Reading Research Quarterly, 40,

guide (NCEE 2009-4045). Washington, DC: National Center 148–182.

for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of McMaster, K. L., Fuchs, D., Fuchs, L. S., & Compton, D. L.

Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education. Retrieved (2005). Responding to nonresponders: An experimental field

from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/wwc/publications/practiceguides/ trial of identification and intervention methods. Exceptional

Gettinger, M., & Stoiber, K. (2008). Applying a response- Children, 71, 445–463.

to-intervention model for early literacy development in National Early Literacy Panel. (2008). Developing early literacy:

low-income children. Topics in Early Childhood Special Report of the National Early Literacy Panel. Washington, DC:

Education, 27, 198–213. National Institute for Literacy.

Gillon, G. T. (2000). The efficacy of phonological awareness inter- Odom, S. L., Buysse, V., & Soukakou, E. (2011). Inclusion for

vention for children with spoken language impairment. Lan- young children with disabilities: A quarter century of research

guage, Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 31, 126–141. perspectives. Journal of Early Intervention, 33, 344–356.

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

Green et al. 259

Odom, S. L., Peck, C. A., Hanson, M., Beckman, P. J., Lieber, J., Snow, C. E., Burns, M. S., & Griffin, P. (Eds.). (1998). Prevent-

Brown, W. H., & Schwartz, I. S. (1996). Inclusion at the pre- ing reading difficulties in young children. Washington, DC:

school level: An ecological systems analysis. Social Policy National Academy Press.

Report: Society for Research in Child Development, 10,18–30. Sulzby, E., & Teale, W. H. (1991). The development of the young

Odom, S. L., Vitztum, J., Wolery, R., Lieber, J., Sandall, S., child and the emergence of literacy. In J. Flood, D. Lapp,

Hanson, M. J., & Horn, E. (2004). Preschool inclusion in the J. R. Squire, & J. M. Jensen (Eds.), Handbook of research on

United States: A review of research from an ecological sys- teaching the English language arts (pp. 300–313). Mahwah,

tems perspective. Journal of Research in Special Educational NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Needs, 4, 17–49. Teale, W. H., & Sulzby, E. (1986). Emergent literacy: Writing and

Peck, C. A., Odom, S. L., & Bricker, D. (1993). Integrating young reading. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

children with disabilities into community programs: Ecologi- Vadasy, P. F., Sanders, E. A., & Peyton, J. A. (2005). Relative

cal perspectives on research and implementation. Baltimore, effectiveness of reading practice or word-level instruction in

MD: Paul H. Brookes. supplemental tutoring: How text matters. Journal of Learning

Phillips, B. M., Clancy-Menchetti, J., & Lonigan, C. J. (2008). Disabilities, 38, 364–380.

Successful phonological awareness instruction with preschool Vaughn, S., & Fuchs, L. S. (2006). A response to competing

children: Lessons from the classroom. Topics in Early Child- views: A dialogue on response to intervention. Assessment for

hood Special Education, 28, 3–17. Effective Intervention, 32, 58–61.

Pullen, P. C., & Justice, L. M. (2003). Enhancing phonological Vaughn, S., Mathes, P., Linan-Thompson, S., Cirino, P., Carlson, C.,

awareness, print awareness, and oral language skills in pre- Pollard-Durodola, S., & Francis, D. (2006). Effectiveness of

school children. Intervention in School & Clinic, 39, 87–98. an English intervention for first-grade English language learn-

Rafferty, Y., Piscitelli, V., & Boettcher, C. (2003). The impact of ers at risk for reading problems. Elementary School Journal,

inclusion on language development and social competence among 107, 153–180.

preschoolers with disabilities. Exceptional Children, 69, 467–479. Wagner, R. K., & Torgesen, J. K. (1987). The nature of phonologi-

Scarborough, H. S. (1990). Very early language deficits in dyslexic cal processing and its casual role in the acquisition of reading

children. Child Development, 61, 1728–1743. skills. Psychological Bulletin, 101, 192–212.

Scarborough, H. S. (2001). Connecting early language and liter- Wagner, R. K., Torgesen, J. K., & Rashotte, C. A. (1994). Devel-

acy to later reading (dis)abilities: Evidence, theory, and prac- opment of reading-related phonological processing abilities:

tice. In S. B. Neuman & D. K. Dickinson (Eds.), Handbook New evidence of bidirectional causality from a latent vari-

of early literacy research (Vol. 1, pp. 97–110). New York, able longitudinal study. Developmental Psychology, 30,

NY: Guilford. 73–87.

Shaywitz, S. E., Escobar, M. D., Shaywitz, B. A., Fletcher, J. M., Whitehurst, G. J., & Lonigan, C. J. (1998). Child development and

& Makuch, R. (1992). Evidence that dyslexia may represent emergent literacy. Child Development, 69, 848–872.

the lower tail of the lower distribution of reading ability. Wilkinson, K. M. (1998). Profiles of language and communication

New England Journal of Medicine, 326, 145–150. skills in autism. Mental Retardation and Developmental Dis-

Shonkoff, J. P., & Phillips, D. A. (2000). From neurons to neigh- abilities Research Reviews, 4, 73–79.

borhoods: The science of early childhood development. Winter, S. (1999). The early childhood inclusion model: A pro-

Washington, DC: National Academy Press. gram for all children. Olney, MD: Association for Childhood

Smith, M. W., & Dickinson, D. K. (2002). User’s guide to the Education International.

early language and literacy classroom observation toolkit. Zill, N., & Resnick, G. (2006). Emergent literacy of low-income

Baltimore, MD: Paul H. Brookes. children in Head Start: Relationships with child and family

Smith, V., Mirenda, P., & Zaidman-Zait, A. (2007). Predictors of characteristics, program factors, and classroom quality. In

expressive vocabulary growth in children with autism. Journal D. K. Dickenson & S. B. Neuman (Eds.), Handbook of early

of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 50, 149–160. literacy research (Vol. 2, pp. 347–371). New York, NY: Guilford.

Downloaded from tec.sagepub.com by Katherine Green on November 6, 2015

View publication stats

You might also like

- Maths Addition and Subtraction WorkbookDocument26 pagesMaths Addition and Subtraction WorkbookMar Attard100% (3)

- University of Mindanao: Self-Instructional Manual (SIM) For Self-Directed Learning (SDL)Document44 pagesUniversity of Mindanao: Self-Instructional Manual (SIM) For Self-Directed Learning (SDL)Pia SurilNo ratings yet

- SYLLABUS Intercultural CommunicationDocument6 pagesSYLLABUS Intercultural CommunicationSone VipgdNo ratings yet

- Moore Etal2014Document14 pagesMoore Etal2014eebook123456No ratings yet

- Chapter 9 - Using Standardized Measurements To Look at Cognitive DevelopmentDocument4 pagesChapter 9 - Using Standardized Measurements To Look at Cognitive Developmentapi-381559096No ratings yet

- Social Stories and Young Children - Strategies For Teachers (2012)Document8 pagesSocial Stories and Young Children - Strategies For Teachers (2012)SarahNo ratings yet

- Preschool Life Skills Training Using The Response To Intervention Model With Preschoolers With Developmental DisabilitiesDocument21 pagesPreschool Life Skills Training Using The Response To Intervention Model With Preschoolers With Developmental Disabilitiesdecamachado78No ratings yet

- Parent Education in Early Intervention: A Call For A Renewed FocusDocument12 pagesParent Education in Early Intervention: A Call For A Renewed FocusAlina FlorentinaNo ratings yet

- Castro Action ResearchDocument14 pagesCastro Action ResearchHorts JessaNo ratings yet

- Dennis Et Al 2023 The Effects of Practice Based Coaching On The Implementation of Shared Book Reading Strategies ForDocument16 pagesDennis Et Al 2023 The Effects of Practice Based Coaching On The Implementation of Shared Book Reading Strategies ForxxshellybellxxNo ratings yet

- Teachers' Use of Drilling Teaching Method and Spelling Challenges For Students With Dyslexia in Form Two Secondary Schools in CameroonDocument10 pagesTeachers' Use of Drilling Teaching Method and Spelling Challenges For Students With Dyslexia in Form Two Secondary Schools in CameroonEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- Tekin Iftar2017 PDFDocument21 pagesTekin Iftar2017 PDFVictor Martin CobosNo ratings yet

- Vivanti Et Al ESDM 2019Document11 pagesVivanti Et Al ESDM 2019CamilaVegaNo ratings yet

- Collaborative Strategic Reading For Students WithDocument20 pagesCollaborative Strategic Reading For Students WithNadiya AmeliaNo ratings yet

- Content ServerDocument17 pagesContent ServerMV FranNo ratings yet

- SocialtalkDocument14 pagesSocialtalkIuli AnaNo ratings yet

- Deped - Division of Quezon: "Creating Possibilities, Inspiring Innovations"Document20 pagesDeped - Division of Quezon: "Creating Possibilities, Inspiring Innovations"Dar JNo ratings yet

- Research Category Research Agenda CategoryDocument7 pagesResearch Category Research Agenda CategoryIris AriesNo ratings yet

- Effective New Normal Learning Strategies For Kindergarten Pupils in Antipuluan Elementary School Sy. 2020-2021Document30 pagesEffective New Normal Learning Strategies For Kindergarten Pupils in Antipuluan Elementary School Sy. 2020-2021Rhea SuaminaNo ratings yet

- Investigating The Alignment Between English Language Arts Curricula Developed For Students With Significant Intellectual Disability and The CCSSDocument12 pagesInvestigating The Alignment Between English Language Arts Curricula Developed For Students With Significant Intellectual Disability and The CCSSShining DiamondNo ratings yet

- 2018 - Lshss-Dyslc-18-0007 OkDocument12 pages2018 - Lshss-Dyslc-18-0007 OkAyundia Ruci Yulma PutriNo ratings yet

- Preschool ScreeningDocument7 pagesPreschool ScreeningΧριστινα ΣαπανιδουNo ratings yet

- Observational LearningDocument20 pagesObservational LearningAlexandra AddaNo ratings yet

- Problem-Based Learning (PBL) : Assessing Students' Learning Preferences Using VARKDocument9 pagesProblem-Based Learning (PBL) : Assessing Students' Learning Preferences Using VARKJuliance PrimurizkiNo ratings yet

- Group 8 Final DocumentationDocument10 pagesGroup 8 Final DocumentationCeline Fernandez CelociaNo ratings yet

- Basic Research On Readiness and Challenges of ParentsDocument21 pagesBasic Research On Readiness and Challenges of ParentsjnprintanddesignNo ratings yet

- 3 - 2015 Terapia Semantica Lexica NiñosDocument12 pages3 - 2015 Terapia Semantica Lexica Niñosroberthjonathan5No ratings yet

- TitlessDocument8 pagesTitlessCharito M MirafuentesNo ratings yet

- Module 17Document9 pagesModule 17kateaubreydemavivasNo ratings yet

- Parental ChildDocument9 pagesParental ChildFadia Talia Salsabila HerviNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Cognitive in Children With LearDocument6 pagesCharacteristics of Cognitive in Children With LearNampatnampat 6969No ratings yet

- PR1 222222 3 PaynaleeeeeeeeeDocument18 pagesPR1 222222 3 Paynaleeeeeeeeepaksick143No ratings yet

- Improving Narrative Skills in Young Children With Delayed Language DevelopmentDocument17 pagesImproving Narrative Skills in Young Children With Delayed Language DevelopmentMiguel Carreño AlvarezNo ratings yet

- A Study On The Level of Self Esteem Among Children With Learning DisabilityDocument5 pagesA Study On The Level of Self Esteem Among Children With Learning DisabilityEditor IJTSRDNo ratings yet

- The Links Between Early Experiences and Responses in The ClassroomDocument7 pagesThe Links Between Early Experiences and Responses in The ClassroomAnghel Roxana MihaelaNo ratings yet

- Berg and WehbyDocument7 pagesBerg and Wehbyapi-296658056No ratings yet

- Autism Research - 2022 - Vivanti - Characteristics of Children On The Autism Spectrum Who Benefit The Most From ReceivingDocument10 pagesAutism Research - 2022 - Vivanti - Characteristics of Children On The Autism Spectrum Who Benefit The Most From ReceivingMichele CezarNo ratings yet

- Fox 2011Document16 pagesFox 2011Ana VillaresNo ratings yet

- Effects of PEERS® Social Skills Training On Young Adults With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities During CollegeDocument27 pagesEffects of PEERS® Social Skills Training On Young Adults With Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities During CollegeLeandro Orias de AraujoNo ratings yet

- Final Research Proposal 111Document37 pagesFinal Research Proposal 111Marie Cris DegamaNo ratings yet

- Ed101 Module Lesson 3 and 4 AssessmentDocument12 pagesEd101 Module Lesson 3 and 4 AssessmentClifford Villarubia LaboraNo ratings yet

- Bulihan, City of Malolos, Bulacan 3000Document2 pagesBulihan, City of Malolos, Bulacan 3000tereNo ratings yet

- A Three Dimensional Model For The Inclusion of Children With DisaDocument10 pagesA Three Dimensional Model For The Inclusion of Children With DisaAllea CapitaneaNo ratings yet

- 2430-Article Text-12537-1-10-20180604Document8 pages2430-Article Text-12537-1-10-20180604Rossel Jay PajoNo ratings yet

- I Year M.Sc. Nursing Psychiatric Nursing. YEAR 2011-2013Document20 pagesI Year M.Sc. Nursing Psychiatric Nursing. YEAR 2011-2013Archana YadavNo ratings yet

- Project Gabay-Salakay For Struggling Third Graders in ReadingDocument6 pagesProject Gabay-Salakay For Struggling Third Graders in ReadingPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Completed ResearchDocument23 pagesCompleted ResearchNELSONNo ratings yet

- Class Combination 1Document29 pagesClass Combination 1joerenaguila17No ratings yet

- Project Kabasabado For The Third Graders' Reading DifficultiesDocument5 pagesProject Kabasabado For The Third Graders' Reading DifficultiesPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Exploring Culturally Responsive Pedagogies in Science: Story 3Document8 pagesExploring Culturally Responsive Pedagogies in Science: Story 3KhemHuangNo ratings yet

- 06 Peer Effects in Early Childhood Education Testing The Assumptions of Special Education InclusionDocument9 pages06 Peer Effects in Early Childhood Education Testing The Assumptions of Special Education InclusionCAMILA MACARENA MUÑOZ VERGARANo ratings yet

- Effective Reading Remediation Instructional Strate PDFDocument6 pagesEffective Reading Remediation Instructional Strate PDFCarlo LegaspinaNo ratings yet

- ProjectEASE PDFDocument24 pagesProjectEASE PDFBenedict De los ReyesNo ratings yet

- Us 2 Observation Lesson PlanDocument12 pagesUs 2 Observation Lesson Planapi-363732356No ratings yet

- CHAPTER1,2,3Document54 pagesCHAPTER1,2,3Jaymike T. CarbonillaNo ratings yet

- English Reading Proficiency and Academic Performance Among Lower Primary School Children in GhanaDocument10 pagesEnglish Reading Proficiency and Academic Performance Among Lower Primary School Children in GhanaPeggy Lalita FedoraNo ratings yet

- Kohler 1999Document11 pagesKohler 1999Ana VillaresNo ratings yet

- Handling Disruptive Behaviors of Students in San Jose National High SchoolDocument5 pagesHandling Disruptive Behaviors of Students in San Jose National High SchoolInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- The Third TeacherDocument3 pagesThe Third Teacherrebecca.hillman.perezNo ratings yet

- Vocabulary Acquisition of A Four-Year-Old Child Through Piaget's Accommodation TheoryDocument13 pagesVocabulary Acquisition of A Four-Year-Old Child Through Piaget's Accommodation TheoryPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Characteristics of Children On The Autism Spectrum Who Benefit The Most From ReceivingDocument10 pagesCharacteristics of Children On The Autism Spectrum Who Benefit The Most From ReceivingLucas De Almeida MedeirosNo ratings yet

- GE JD21 Mirabelle M. BendanilloDocument5 pagesGE JD21 Mirabelle M. Bendanillomolorj92No ratings yet

- Lacanian Theory in Literary Criticism.: October 2019Document7 pagesLacanian Theory in Literary Criticism.: October 2019Amani Adam DawoodNo ratings yet

- Issues in Text Corpus Generation: January 2019Document17 pagesIssues in Text Corpus Generation: January 2019Amani Adam DawoodNo ratings yet

- Corpus Linguistics Part 1Document30 pagesCorpus Linguistics Part 1Amani Adam DawoodNo ratings yet

- Regional & Social Dialect: Muhammad Fahmi Nur Najwa Syuhada Nur Syamilia TahfizahDocument20 pagesRegional & Social Dialect: Muhammad Fahmi Nur Najwa Syuhada Nur Syamilia TahfizahAmani Adam DawoodNo ratings yet

- Syllabus - 2016 (ATTM3) - ENGDocument7 pagesSyllabus - 2016 (ATTM3) - ENGgurky33No ratings yet

- Find Someone Who 2nd Conditional TeacherDocument2 pagesFind Someone Who 2nd Conditional TeacherPutriRahimaSariNo ratings yet

- Agk New-Syllabus 2014 SingleDocument64 pagesAgk New-Syllabus 2014 Singlegkruet77No ratings yet

- Gordon Neufeld, Un Reconocido Psicólogo Evolucionista Dice Lo SiguienteDocument3 pagesGordon Neufeld, Un Reconocido Psicólogo Evolucionista Dice Lo Siguientepablo0% (1)

- Integration of Modern Science N Vedic Science PaperDocument32 pagesIntegration of Modern Science N Vedic Science Papergaurav gupteNo ratings yet

- Form AIFF D LicenseDocument2 pagesForm AIFF D LicenseAswin KrishnaNo ratings yet

- Study Centre: Ft-2022 Engg BatchesDocument2 pagesStudy Centre: Ft-2022 Engg BatchesSOHAIL MOHAMMEDNo ratings yet

- Feedback Comment BankDocument5 pagesFeedback Comment Bankvelezm1No ratings yet

- MA2Document5 pagesMA2LauraNo ratings yet

- Who Does Marketing Research?Document12 pagesWho Does Marketing Research?Stephanie Venenoso0% (1)

- Chapter 13 Relevant Costs For Decision Making: True/False QuestionsDocument140 pagesChapter 13 Relevant Costs For Decision Making: True/False QuestionsexgayssNo ratings yet

- Perdev 11Document6 pagesPerdev 11Antonette Dublin100% (1)

- Mis InfoDocument10 pagesMis InfokaivanNo ratings yet

- Adult LearningDocument16 pagesAdult LearningCamille Adle100% (1)

- Lecture 1Document2 pagesLecture 1aaaNo ratings yet

- Skill Mismatch in EuropeDocument46 pagesSkill Mismatch in EuropeMaite PrietoNo ratings yet

- SPED410 Syllabus 2014 Talbott-3Document9 pagesSPED410 Syllabus 2014 Talbott-3Julia AydinNo ratings yet

- Openmind 3 Unit 1 Class Video Worksheet Teacher's NotesDocument2 pagesOpenmind 3 Unit 1 Class Video Worksheet Teacher's NotesTatiana Acosta Malpica100% (1)

- 4th Annual YCC Global Conference - ProgramDocument18 pages4th Annual YCC Global Conference - Programrichardalbert732No ratings yet

- Mariage ContractDocument98 pagesMariage ContractrenzeiaNo ratings yet

- Activity ProposalDocument2 pagesActivity ProposalGerry Brital100% (1)

- VMG-Week-1 2Document5 pagesVMG-Week-1 2Alyssa Crizel CalotesNo ratings yet

- Developing A Strategic Perspective For Construction Industry in BotswanaDocument16 pagesDeveloping A Strategic Perspective For Construction Industry in BotswanaYaredo MessiNo ratings yet

- Weekly Home Learning Plan: Subject: Subject Code InstructorsDocument8 pagesWeekly Home Learning Plan: Subject: Subject Code InstructorsPrincess Joy CastilloNo ratings yet

- ACSEE 2023 TimetableDocument2 pagesACSEE 2023 TimetableDaniel EudesNo ratings yet

- Academic Skills EssayDocument57 pagesAcademic Skills Essayb723e05c100% (2)

- Placement BrochureDocument34 pagesPlacement BrochureSHAIK TIPPUNo ratings yet