Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Autocratic Leadership

Uploaded by

Gumilang BreakerCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Autocratic Leadership

Uploaded by

Gumilang BreakerCopyright:

Available Formats

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology

http://jcc.sagepub.com

Autocratic Leadership Around the Globe: Do Climate and Wealth Drive Leadership Culture?

Evert Van de Vliert

Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 2006; 37; 42

DOI: 10.1177/0022022105282294

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://jcc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/37/1/42

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

International Association for Cross-Cultural Psychology

Additional services and information for Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://jcc.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://jcc.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations (this article cites 17 articles hosted on the

SAGE Journals Online and HighWire Press platforms):

http://jcc.sagepub.com/cgi/content/refs/37/1/42

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

JOURNAL

10.1177/0022022105282294

Van de Vliert

OF/ AUTOCRA

CROSS-CUL

TIC

TURAL

LEADERSHIP

PSYCHOLOGY

WORLDWIDE

AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP AROUND THE GLOBE

Do Climate and Wealth Drive Leadership Culture?

EVERT VAN DE VLIERT

University of Groningen

Common autocratic leader characteristics in a country’s organizations are conceptualized here as cultural

adaptations to noncultural components of the national environment, such as the harshness of cold or hot cli-

mate and the level of wealth. A secondary analysis of managerial survey data gathered in 61 cultures is used

to retest the recently formulated theory that climatic demands matched by wealth-based resources are posi-

tively linked to democratic leadership, whereas climatic demands unmatched by wealth-based resources are

negatively linked to democratic leadership. In further support of this cultural leadership theory, autocratic

leadership, as the opposite of democratic leadership, is seen as less effective in richer countries with more

demanding climates but as more effective in poorer countries with more demanding climates.

Keywords: autocratic leadership; democratic leadership; thermal climate; national wealth; cultural adaptation

It is patent to any intelligent person that different climates produce different fauna

and flora. Why then should they not produce different kinds of people?

—Wheeler, 1946, p. 80

All superiors are unequal, but some are more unequal than others. Cross-cultural differ-

ences in the use of superiority, power, orders, and close supervision are particularly intrigu-

ing. Why, for example, do superiors in Indonesia and Nigeria rely much less on their subor-

dinates as sources of information, and as targets of delegation, than do superiors in Denmark

and the Netherlands (Van de Vliert & Smith, 2004)? Or, more generally, where on earth and

why do leaders tend to overpower or empower the people they lead? Answers to such ques-

tions may help international human resource managers and interventionists, expatriates, and

migrants anticipate and accept or to gradually induce change in the locally dominant rela-

tionships between superiors and subordinates.

In terms of Berry’s (1997) ecocultural model, the present comparative study addresses the

interactive impact of the ecological context of thermal climate and the sociopolitical context

of national wealth on the society-level endorsement of an autocratic rather than democratic

leadership culture. The conceptual part contains a definition and a brief country-level

contextualization of effective autocratic leadership followed by an overview of the cultural,

economic, and climatic explanations of cross-national differences in autocratic and demo-

cratic leadership that have been suggested so far. The gist of the argument is represented in

five schematically interrelated hypotheses. The methodological and empirical parts

contain descriptions of the measures used, the regression analyses applied, and the context-

leadership links found. The concluding part contains a point-by-point discussion of the

restricted scientific claims that can be made.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: For comments and advice, I thank Deanne N. Den Hartog, Peter B. Smith, Nico W. Van Yperen, and two anony-

mous reviewers of this journal.

JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY, Vol. 37 No. 1, January 2006 42-59

DOI: 10.1177/0022022105282294

© 2006 Sage Publications

42

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Van de Vliert / AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP WORLDWIDE 43

EXPLANATIONS AND HYPOTHESES

AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP AND NATIONAL ENVIRONMENTS

Compared to democratic superiors, autocratic superiors act in more self-centered ways.

They make decisions more unilaterally and supervise subordinates’ work activities more

closely (Muczyk & Reimann, 1987). Given that organizations are embedded in widely dif-

ferent cultural environments, economic environments, and climatic environments (Parker,

1997), it is unlikely that no worldwide differences in the endorsement, adoption, and per-

ceived effectiveness of autocratic leadership would occur. Whereas cross-national differ-

ences in the appreciation and implementation of autocratic and democratic leadership in

organizations are indeed obvious and well documented (e.g., Den Hartog et al., 1999;

Hofstede, 2001; House et al., 1999; House, Hanges, Javidan, Dorfman, & Gupta, 2004),

their explanation has recently become a disputed issue. Is this unmistakable cross-national

variation in the extent to which autocratic leadership in organizations is endorsed, expected,

enacted, and accepted culture driven, economy driven, or climate driven, or is there another

explanation?

CULTURAL EXPLANATION?

Here, borrowing from House et al. (1999), culture refers to a set of “shared motives, val-

ues, beliefs, identities, and interpretations or meanings of significant events that result from

common experiences of members of collectives and are transmitted across age generations”

(p. 184). With regard to leadership, national culture is usually conceptualized and investi-

gated as a set of independent variables and as having a pervasive influence on the leadership

construals and leader behavior of its members. Hundreds of studies have shown that a coun-

try’s culture helps to explain leadership construals (e.g., Brodbeck et al., 2000; Dorfman,

Hanges, & Brodbeck, 2004; Gerstner & Day, 1994; Hofstede, 2001; House et al., 1999;

Schmidt & Yeh, 1992; Shaw, 1990; Wong & Birnbaum-More, 1994), leader behavior (e.g.,

Smith, Peterson, & Misumi, 1994; Smith et al., 2002), relations between leadership

construals and leader behavior (e.g., Smith, Misumi, Tayeb, Peterson, & Bond, 1989), rela-

tions between leader behavior and behavioral consequences (e.g., Hofstede, 2001; Williams,

Whyte, & Green, 1966), and so forth.

Now that so many studies have significantly advanced our understanding of leadership

phenomena as consequences of national culture, the time is ripe for investigating common

leadership construals in a country’s organizations as cultural adaptations to noncultural con-

texts. Being realistic about what can be accomplished at any one time in an inquiry, I

restricted myself to a historical economic explanation, two climatic explanations, and two

climate-by-wealth explanations of autocratic leadership in organizations around the globe.

ECONOMIC EXPLANATION?

Only when humans changed their primary mode of subsistence from hunting animals to

herding them and from gathering plants to cultivating them did autocratic leadership develop

(Nolan & Lenski, 1999, pp. 103-109, 189-191). The transition from sampling food to pro-

ducing food and from a nomadic lifestyle to a sedentary lifestyle gradually reduced environ-

mental complexity and uncertainty, thus allowing for more directive leadership (cf., Duncan,

1972; Mintzberg, 1979). A powerful and often literate urban elite started to make the

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

44 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

necessary economic decisions, to enforce implementation, and to autocratically control the

economic surplus (e.g., Bibby, 1965; Lenski, 1966; Service, 1975). The resulting agrarian

societies were characterized by centralized authority, chief executive control, and vertical

specialization anchored by a few “haves” and a huge majority of “have nots.”

Even today, many countries with predominantly agrarian populations, including Albania,

China, Colombia, India, Indonesia, Kazakhstan, Morocco, and Zambia, are still autocrati-

cally led, directly by members of a governing class (Karatnycky, 2001) and indirectly by col-

laborating retainers, clergymen, and merchants in organizations (Nolan & Lenski, 1999, p.

190). As a likely consequence, through processes of socialization and internalization, supe-

riors and subordinates in organizations in these industrializing agrarian societies have

learned to value and practice the giving and obeying of orders and to view autocratic

leadership as effective.

The next major transition, from agrarian society to industrial society, was and is, first of

all, a matter of growing economic development and increasing socioeconomic complexity.

Under these circumstances, organizational leaders can no longer adequately manage on their

own and find it necessary to delegate decision-making discretion to others (Duncan, 1972;

Mintzberg, 1979). Indeed, growing development and increasing complexity tend to propel

societies in the direction of higher income, better education, and more political and eco-

nomic participation (United Nations Development Programme, 2001), as well as smaller

power distances in organizations (Hofstede, 2001, p. 519). This cluster of economy-driven

trends tends to empower subordinates and, through it, makes top-down decision making and

close supervision in their organizations less important, less feasible, and less effective (cf.,

Gerstner & Day, 1994; Hofstede, 2001; Leana, 1987; Sagie & Koslowsky, 2000). Together,

the agrarian and advanced industrial stages of societal development suggest that autocratic

leadership will be seen as less effective and attractive in richer countries. This perspective led

to the first hypothesis, representing the economic explanation.

Hypothesis 1: The perceived effectiveness of autocratic leadership is lower in richer countries.

CLIMATIC EXPLANATION?

Here, climate refers to the generalized cold or hot weather of an area. Whereas the

weather changes continuously, climate has been extraordinarily stable for the past 10,000

years (Burroughs, 1997). Whereas cold and hot weather tend to have immediate

physiopsychological effects at the individual and organizational levels, cold and hot climates

tend to have long-term macrosociological effects at the societal and global levels.

In the field of organizational behavior, Peterson and Smith (1997) have criticized Van de

Vliert and Van Yperen (1996) for confusing weather effects and climatic effects on power

distance and role overload. All of them can be criticized for making no distinction between

geoclimatic effects and bioclimatic effects. Geoclimate, the mean temperature level, varies

from cold at the icecaps to hot at the equator. Bioclimate, the average deviation from a com-

fortable temperature level, varies from harsh at latitudes closer to the icecaps (e.g., Canada,

Finland), in countries with land climates (e.g., Austria, China), and in desert areas (e.g.,

Sudan, Niger) to temperate in countries with sea climates at latitudes closer to the equator

(e.g., Costa Rica, Philippines). Besides, in geoclimate, equally large between-country differ-

ences in temperature have the same weight at all temperature levels, whereas in bioclimate,

equally large between-country differences in temperature tend to weigh heavier at more

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Van de Vliert / AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP WORLDWIDE 45

extreme temperature levels (cf., Parsons, 1993; Scholander, Hock, Walters, Johnson, &

Irving, 1950).

Although common autocratic and democratic leadership cultures in a country’s organiza-

tions have been related to climate, theory building has so far been inaccurate and simplistic

because no distinction was made between geoclimate and bioclimate, let alone between

main and interactive effects of geoclimate and bioclimate on leadership. Following is an

overview of the speculative parts of geoclimatic and bioclimatic explanations of leadership

cultures, summarized in two hypotheses about cross-national differences in the perceived

effectiveness of autocratic leadership. The subsequent sections contain two additional

hypotheses representing interactive geoclimate-by-wealth and bioclimate-by-wealth

explanations of autocratic leadership cultures.

Geoclimatic explanation. According to Hofstede (2001), “a country’s geographic posi-

tion is a fundamental fact that is bound to have a strong effect on the subjective culture of its

inhabitants, as this culture is shaped over many generations” (p. 116). For that reason, he was

not surprised to find that geographic latitude as a rough global indicator of climate was nega-

tively linked to cultural power distance, a conglomeration of autocratic and persuasive/

paternalistic leadership. Hofstede (2001, pp. 115-117) argued that the linear cold-hot differ-

ence in climate is at the beginning of a causal chain because warmer environments are less

problematic and easier to cope with. In colder climates, survival and population growth are

more dependent on human intervention in nature, with the complicating effects that there is

more need for technology, more technological momentum for change, more two-way teach-

ing, and more questioning of authority. In subtropical and tropical climates, by contrast,

there is less need for human intervention and for technology, leading to a more static society

in which teachers are omniscient and teaching is one way and to less questioning of author-

ity.

Related studies of the association between geoclimate and power distance similarly

showed that more tropical climates value power distance more and have more practices of

power distance (Carl, Gupta, & Javidan, 2004), that organizations in countries with colder

climates are less centralized and less vertically differentiated, and that employees in colder

countries attach greater importance to egalitarian commitment and autonomy (Van de Vliert

& Van Yperen, 1996). Together, these findings and speculative interpretations support the

viewpoint that societies at higher latitudes have to cope with more complex climatic envi-

ronments and, therefore, in line with Duncan’s (1972) and Mintzberg’s (1979) systems-

theoretical framework, tend to disapprove of autocratic leadership to a greater extent. This

notion that more complex colder environments decrease the endorsement and adoption of

autocratic leadership led to the second hypothesis, representing the geoclimatic explanation.

Hypothesis 2: The perceived effectiveness of autocratic leadership is lower in countries with colder

geoclimates.

Bioclimatic explanation. There is reason to expect that the negative relationship between

climatic temperature and leadership in Hypothesis 2 is misleading because, like all warm-

blooded species, humans thrive in temperate climates. The colder or hotter the climate, the

more adaptations are required. Acclimatization, that is, long-term adjustment in anatomy

and physiology, is not enough (Parsons, 1993). Climate-contingent needs for thermal com-

fort, nutrition, and health require that humans continuously use, adjust, and organize a vari-

ety of elements from their environment. Harsher—colder or hotter—climates require special

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

46 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

clothing, housing, and working arrangements; special organizations for the production,

transportation, trade, and storage of food; special care and cure facilities; and so forth (for

some early formulations of the bioclimatic impact on organizational behavior, see

McClelland, 1961, pp. 383-388; Triandis, 1973).

Some large cross-national studies (Van de Vliert, 2003; Van de Vliert, Schwartz,

Huismans, Hofstede, & Daan, 1999) reported a pattern of links between a country’s

bioclimate and its culture. Compared with employees in colder and hotter countries, employ-

ees in countries with temperate climates attach more importance to earnings, recognition,

and mastery-oriented advancement and challenge than to good working relationships and

desirable living conditions. The research team assumed that the greater investments in adapt-

ing to cold climates with prolonged winters and to hot climates with scorching summers have

led to the development of cultural customs characterized by sacrifice, delay of gratification,

and cooperation rather than more selfish cultural customs characterized by dominance and

aggressive competition.

If these bioclimate-culture links rest on valid observations, autocratic leadership will be

less appropriate and prevalent in organizations located in countries with harsher climates. In

support of this expectation, Van de Vliert and Smith (2004) showed that organizational supe-

riors in countries with more demanding—colder or hotter—climates adopted more demo-

cratic styles of leadership by relying more on their subordinates as sources of information

and as targets of delegation. Taken together, these physiology-based considerations and

empirical associations led to the third hypothesis, representing the bioclimatic explanation.

Hypothesis 3: The perceived effectiveness of autocratic leadership is lower in countries with more

demanding—colder or hotter—bioclimates.

It is worth mentioning that support for Hypothesis 3 is independent of support for

Hypothesis 2. If the curve between thermal climate and perceived effectiveness of autocratic

leadership has an upward slope, it supports Hypothesis 2 but not Hypothesis 3; if this curve

has a predominantly upward slope ending in a downward slope, it supports both hypotheses;

if this curve has a predominantly downward slope, it supports Hypothesis 3 but not

Hypothesis 2.

CLIMATE-BY-WEALTH EXPLANATION?

Montesquieu (1748) was the first to recognize that atmospheric climate and national

wealth may have joint effects on human functioning. The key breakthrough made by

Montesquieu is the notion that income is generated not so much for income’s sake but to sat-

isfy climate-contingent human needs (Parker, 2000, pp. 24-26). In essence, Montesquieu

saw national wealth as a determinant of the link between climate and human perceptions and

behavior. Affluence may indeed alter the impact of climate because capital goods can be

exchanged for homeostatic goods in pursuit of overcoming or mitigating the hardships of

harsh climates (Parker, 2000, pp. 132-135). Hence, it is not inconceivable that climate and

wealth have interactive effects on national culture in general and on the common leadership

culture in a country’s organizations in particular.

From this speculative climate-by-wealth perspective, Van de Vliert and Smith (2004)

recently conducted two studies, a 54-nation comparison of 6,968 middle managers’ reports

of reliance on subordinates as sources of information and a 76-nation comparison of 12,557

top managers’ reports of reliance on subordinates as targets of delegation. Twice they found

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Van de Vliert / AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP WORLDWIDE 47

empirical support for a burgeoning climatic or ecological leadership theory that may be sum-

marized in the following series of four cumulative propositions.

Demands proposition. Basic human needs for thermal comfort, nutrition, and health

make life in colder or hotter climates more demanding than life in temperate climates. Colder

or hotter climates entail nastier weather, a wider variety of thermoregulatory requirements

and adjustments, greater relocation risks, less amenable vegetation, greater risks of food

shortage and food spoilage, stricter diets, more health problems, and so forth (e.g., Parker,

2000; Parsons, 1993; Sachs, 2000; Triandis, 1973).

Resources proposition. National wealth provides a populace with more personal and soci-

etal resources to meet the demands of a less temperate—colder or hotter—climate. As a rule,

homeostatic goods, needed to secure thermal comfort, nutrition, and health, are for sale and

have a price. Money and other capital goods can buy a wide variety of consumables,

immovables, conveniences, appliances, recreational facilities, services, and practices that

help meet the demands of extreme climates.

Match proposition. Greater climatic demands unmatched by wealth-based climatic

resources require greater cognitive, affective, and behavioral investments in satisfying exis-

tence needs. The acquisition of homeostatic goods requires more selfish attention, anxiety,

and labor at the expense of alternative investments in one’s sociopsychological networks and

functioning. Consequently, in conjunction with lower collective income, more demanding

climates are expected to produce more selfish, if not competitive, cultures. In contrast,

greater climatic demands matched by wealth-based climatic resources satisfy existence

needs, thus allowing greater cognitive, affective, and behavioral investments in satisfying

one’s own and others’ needs for relatedness, collaboration, and coordination. Consequently,

in conjunction with higher collective income, more demanding climates are expected to

produce more cooperative cultures.

Leadership proposition. Given that leaders in countries with more demanding climates

unmatched by climatic resources tend to act in more selfish and competitive ways, they will

consistently tend to adopt and endorse subordinate-oriented leadership to a lesser extent.

Conversely, given that leaders in countries with more demanding climates matched by cli-

matic resources tend to act in more cooperative ways, they will consistently tend to adopt and

endorse subordinate-oriented leadership to a greater extent. In other words, different organi-

zational leaders thrive in different climate-by-wealth niches on earth: autocratic leaders

under circumstances of harshness and poverty, democratic leaders under circumstances of

harshness and wealth, and moderately autocratic/democratic leaders in temperate climates

irrespective of wealth.

This rudimentary leadership theory has been tested for the occurrence of democratic lead-

ership under various bioclimatic conditions. The present study extends this line of research

by testing whether the theory also holds for the perceived effectiveness of autocratic leader-

ship. In addition, this study is the first to take into account that the theory can be tested for

either increasingly cold or increasingly hot climates, yielding geoclimate-by-wealth expla-

nations of leadership culture, or for both colder and hotter climates, yielding bioclimate-by-

wealth explanations of leadership culture. The geoclimate-by-wealth prediction in Hypothe-

sis 4 qualifies Hypotheses 1 and 2, whereas the bioclimate-by-wealth prediction in

Hypothesis 5 qualifies Hypotheses 1 and 3.

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

48 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

TABLE 1

Interrelations Among Explanations of Autocratic Leadership

Economy Driven?

Climate Driven? No Yes

No Other explanation? Economic explanation

(null hypothesis) (Hypothesis 1)

Yes Climatic explanation Climate-by-wealth explanation

(Hypotheses 2 and 3) (Hypotheses 4 and 5)

Hypothesis 4: The perceived effectiveness of autocratic leadership is lower in richer countries with

more demanding—colder—geoclimates but higher in poorer countries with more demanding

geoclimates.

Hypothesis 5: The perceived effectiveness of autocratic leadership is lower in richer countries with

more demanding—colder or hotter—bioclimates but higher in poorer countries with more

demanding bioclimates.

INTERRELATIONS AMONG EXPLANATIONS

The main explanations of the cross-national differences in autocratic leadership culture

can be further clarified using the two-by-two scheme in Table 1. As indicated, the perceived

effectiveness of autocratic leadership is neither economy driven nor climate driven if the null

hypothesis cannot be rejected, is one-sidedly economy driven if only Hypothesis 1 is sup-

ported, is one-sidedly climate driven if only Hypothesis 2 or Hypothesis 3 is supported, and

is driven by climate and wealth in concert if either Hypothesis 4 or Hypothesis 5 is sup-

ported. Irrespective of whether the hypotheses are supported or rejected, autocratic leader-

ship culture may still be driven by economic conditions other than national wealth, climatic

conditions other than thermal climate, or the country’s historical, political, institutional, and

religious context (cf., Dorfman, 1996).

METHOD

SAMPLE

The study was a secondary analysis of survey data gathered by more than 170 researchers

of Global Leadership and Organizational Behavior Effectiveness (GLOBE; for research

details, see House & Hanges, 2004). The GLOBE group gathered data in 61 cultures, repre-

senting all major regions of the world. In three multicultural countries, more than one culture

was sampled (East and West Germans, German-speaking and French-speaking Swiss, and

White and Black South Africans). Within each culture, middle managers from domestic

organizations in at least two target industries (food processing, financial services, and tele-

communications services) were sampled (N = 17,370, range = 27 to 1,790 per culture, M =

285, SD = 237). Clearly, this sample is not representative of all cultures and countries. It does

represent, however, a relevant range of variation in the environmental conditions of climate

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Van de Vliert / AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP WORLDWIDE 49

and wealth (e.g., temperate/poor: Ecuador, Zambia; temperate/rich: New Zealand, Taiwan;

demanding/poor: Kazakhstan, Turkey; demanding/rich: Germany, Slovenia) that might

influence leadership construals and leader behavior in work settings.

MEASURES

Dependent variable: Autocratic leadership. The country-level GLOBE dimension used

was the average perceived effectiveness of autocratic leadership (reverse-scored second-

order factor of participative leadership; Dorfman et al., 2004, pp. 713-714; see also Den

Hartog et al., 1999). The measuring instrument was translated from English into the native

language of the participating managers, then translated back into English by another person,

and finally approved or corrected by two members of the GLOBE Coordinating Team. The

managers rated how important each of 10 characteristics and behaviors is for a leader to be

“exceptionally skilled at motivating, influencing, or enabling you, others, or groups to con-

tribute to the success of the organization or task.” The characteristics and behaviors pre-

sented were elitist, ruler, autocratic, dictatorial, domineering, bossy, nonegalitarian,

nondelegator, micromanager, and individually oriented (1 = greatly inhibits a person from

being an outstanding leader and 7 = contributes greatly to a person being an outstanding

leader). The aggregatability (intraclass correlation [ICC]1 = .20), internal consistency

(Cronbach’s α = .85), and interrater reliability (ICC2 = .95) of this measurement scale are

more than acceptable (Hanges & Dickson, 2004, pp. 132-137).

To assess its construct validity, this estimate of autocratic leadership was shown to have

relationships with increases in cultural power distance (r = .51, n = 52, p < .01; Hofstede,

2001, pp. 500-502) and with decreases in country-level leader reliance on subordinates as

sources of information (r = –.45, n = 39, p < .01) and as targets of delegation (r = –.48, n = 51,

p < .01; Van de Vliert & Smith, 2004). The fact that the GLOBE measure showed strong

associations with these three different manifestations of hierarchical interaction reported by

three different samples of organizational employees at three different points in time suggests

that autocratic leadership is a robust syndrome of endorsing and adopting the use of superior-

ity (elitist, ruler, nonegalitarian), power (dictatorial, domineering), orders (bossy,

nondelegator), and close supervision (micromanager, individually oriented).

Although Hanges and Dickson (2004) demonstrated that response bias plays a minor role

in the measurement of autocratic leadership, the country-level ratings may still reflect a

stronger acquiescent response bias (Smith, 2004). To eliminate such bias in scale use, I com-

puted a mean score for GLOBE’s other leadership measures—charismatic/value based,

team oriented, humane oriented, autonomous, and self-protective—and another one for

GLOBE’s nine societal cultural values scales. “There is no substantive reason why these

overall means should vary across nations. They therefore give an estimate of differences in

how rating scales are used within each national sample” (Smith et al., 2002, p. 197). The

autocratic-leadership score was regressed onto the overall means, first for the scores on the

other five leadership dimensions and then for the scores on the nine societal cultural values

scales. The resulting dependent variables were almost identical (r = .95, n = 61, p < .001) and

produced almost identical results. Results for autocratic leadership controlled for the aver-

age level of leadership are reported here because they provide the most conservative test of

the hypotheses. The standardized residuals used for autocratic leadership ranged from –1.94

in Canada and –1.85 in Austria to 1.76 in Mexico and 2.33 in Qatar (for a listing of all values,

see Table 2).

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

50 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

TABLE 2

Values of Autocratic Leadership, Demanding Climate,

and National Wealth for 61 Societal Cultures

b

Independent Variables

Autocratic Demanding Demanding National

a

Leadership Geoclimate Bioclimate Wealth

Albania 1.56 –0.01 1,354 1,250

Argentina –1.71 0.25 1,373 6,800

Australia –1.03 0.15 1,842 17,000

Austria –1.85 –0.32 2,531 20,200

Bolivia –0.09 –2.00 1,051 858

Brazil –1.53 0.64 549 2,680

Canada –1.94 –0.08 4,231 20,800

China 0.62 0.73 2,596 417

Colombia –0.48 –2.34 553 1,500

Costa Rica –0.52 –0.49 403 2,000

Denmark –0.78 –1.22 2,577 24,400

Ecuador –0.83 –1.12 888 1,100

Egypt 1.26 1.85 1,172 730

El Salvador –0.11 1.44 847 1,190

Finland –1.13 –1.27 3,660 26,000

France –0.22 –0.17 1,911 20,400

Georgia 0.58 0.43 1,761 4,530

Germany West –0.89 –0.27 2,632 22,300

Germany East –1.15 –0.27 2,632 22,300

Greece –1.53 0.71 1,262 8,200

Guatemala –0.39 –0.66 525 1,300

Hong Kong 1.09 0.23 696 14,600

Hungary 0.54 –0.17 2,574 5,380

India 0.67 1.74 1,141 369

Indonesia 1.22 0.34 356 680

Iran 0.33 0.97 2,355 6,150

Ireland –0.82 –1.98 1,645 12,000

Israel 0.65 0.59 1,155 12,100

Italy –0.13 –0.03 1,217 18,600

Japan 0.93 0.16 1,192 26,900

Kazakhstan 0.70 0.16 3,858 3,810

Kuwait 0.58 2.04 1,149 16,400

Malaysia 0.33 0.57 411 2,960

Mexico 1.76 –1.02 895 3,660

Morocco 1.05 1.57 1,285 1,060

Namibia –0.45 –0.27 1,050 1,300

Netherlands –0.79 –0.98 2,213 18,300

New Zealand –0.19 –1.62 955 14,900

Nigeria 0.19 0.89 505 314

Philippines –0.56 0.69 464 860

Poland 0.66 –0.76 3,116 4,400

Portugal 0.02 0.02 935 9,000

Qatar 2.33 2.01 1,087 17,000

Russia 1.73 –1.75 3,705 5,990

Singapore –0.02 0.21 327 16,500

Slovenia –0.27 0.75 2,809 12,400

South Africa White –0.82 0.42 1,139 2,960

(continued)

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Van de Vliert / AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP WORLDWIDE 51

TABLE 2 (continued)

a

Independent Variables

Demanding Demanding National

Geoclimate Bioclimate Wealth

South Africa Black 1.09 0.42 1,139 2,960

South Korea 1.05 –0.17 2,505 6,650

Spain 0.70 –0.42 1,545 13,200

Sweden –0.30 –0.81 3,009 25,100

Switzerland French 0.33 –0.29 2,555 33,200

Switzerland German –1.41 –0.29 2,555 33,200

Taiwan 1.18 0.67 813 10,000

Thailand –0.22 1.46 707 1,940

Turkey 0.47 –0.22 2,739 3,670

United Kingdom –0.54 –1.32 1,457 16,700

United States –1.60 1.05 2,787 23,400

Venezuela 1.29 –0.57 482 3,400

Zambia 0.00 0.19 680 420

Zimbabwe –0.62 –0.41 838 640

a. Standardized residual of participative leadership reversed (Dorfman et al., 2004, pp. 713-714) controlled for

acquiescent response bias.

b. Demanding geoclimate is the average of the lowest and highest temperatures in the coldest winter month and in the

hottest summer month regressed on the standard deviation in these four temperature values, whereas demanding

bioclimate is the sum of the squared deviations from 22oC for these four temperature values (Parker, 1997, pp. 203-

226). National wealth is the gross national product per capita in U.S. dollars (Parker, 1997, pp. 45-70).

Independent variable: Demanding geoclimate. Climate is typically estimated in degrees

Celsius during a 30-year period. In countries with many major cities, multiple city averages,

weighted for population, are used (Parker, 1997, pp. 203-226). Because cold countries have

much larger seasonal variations in temperature than warmer countries (r = –.82 for all coun-

tries and r = –.78 for the sample), the average temperature and the variation in temperature

are potentially confounded variables. Geoclimate was therefore operationalized as the

midrange temperature controlled for the winter-summer variation in temperature. Specifi-

cally, I used the standardized residual of the average of the lowest and highest temperatures

in the coldest winter month and in the hottest summer month regressed on the standard devia-

tion in these four temperature values (worldwide range = –3.37 to 2.63, sample range = –2.34

to 2.04; see Table 2).

Independent variable: Demanding bioclimate. Bioclimates are more demanding to the

extent that winters are cold, that summers are hot, or both. The reference point for a temper-

ate climate, 22oC, is not only the highest world temperature in the coldest winter month (on

the Marshall Islands) and the lowest world temperature in the hottest summer month (on the

Faroe Islands; Parker, 1997), but it is also the approximate midpoint of the range of comfort-

able temperatures (cf., Parsons, 1993). It is inadequate to describe the climate-demands rela-

tion using a linear rule. The geoclimatic difference between 20oC and 15oC, for example,

produces a smaller difference in demands than does the geoclimatic difference between

–15oC and –20oC (cf., Parsons, 1993; Scholander et al., 1950). Therefore, demanding

bioclimate was operationalized as the sum of the squared deviations from 22oC for the lowest

and highest temperatures in the coldest winter month and in the hottest summer month

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

52 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

TABLE 3

Means, Standard Deviations, and Intercorrelations

Variable M SD 1 2 3

1. Autocratic leadership 0.00 1.00

2. National wealth 8.54 1.36 –.25*

3. Demanding geoclimate 0.00 1.00 .22 –.20

4. Demanding bioclimate 1,613 1,006 –.19 .47** –.20

NOTE: N = 61 cultures.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

(worldwide range = 146 to 5,777, M = 1,152, SD = 1,028; sample range = 327 to 4,231, M =

1,613, SD = 1,006; see Table 2).

It is important to note that the inaccurate measures of geoclimate and bioclimate in coun-

tries spanning a broad range of latitudes (e.g., Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, China,

Russia, and the United States) form a statistical rather than theoretical problem. By increas-

ing the standard error of the mean and by masking regional within-country variations in cli-

mate, these measures produce conservative estimates of the impact of climate on leadership

culture.

Independent variable: National wealth. As usual, to reduce the skew of the wealth distri-

bution (worldwide range = $115 to $50,000; sample range = $314 to $33,200; Parker, 1997,

pp. 47-70; see Table 2), wealth was operationalized as the natural logarithm of the countries’

gross national product per capita in U.S. dollars (worldwide range = 4.74 to 10.82, M = 7.81,

SD = 1.48; sample range = 5.75 to 10.41, M = 8.54, SD = 1.36). In the Results section, atten-

tion will be paid to the confounding relationship between national wealth and income equal-

ity (r = .63, n = 51, p < .001).

RESULTS

Table 3 contains a listing of the means, standard deviations, and intercorrelations of the

variables used. In support of Hypothesis 1, autocratic leadership was seen as somewhat less

effective in richer countries (r = –.25, p < .05). By contrast, there was no support for the

expectations in Hypotheses 2 and 3 that autocratic leadership is endorsed less in countries

with colder geoclimates (r = .22, ns) or in countries with less temperate—colder or hotter—

bioclimates (r = –.19, ns). A retest of Hypothesis 2, controlling for bioclimate, and a retest of

Hypothesis 3, controlling for geoclimate, did not change the results because geoclimate and

bioclimate are unrelated (r = –.20, ns).

To test Hypotheses 4 and 5, after standardizing the predictors, I entered geoclimate or

bioclimate, wealth, and the climate-by-wealth interaction term in a hierarchical regression

analysis. As reported in Table 4, Model 1, the geoclimate-by-wealth composite did not pre-

dict the endorsement of autocratic leadership. Thus, the joint impact of geoclimate and

wealth, as formulated in Hypothesis 4, received no support. In Model 2, a highly significant

result surfaced for the interactive effect of bioclimate and wealth on the perceived effective-

ness of autocratic leadership (∆R2 = .19, Β = –.54, p < .001). As shown in Figure 1, and in

support of Hypothesis 5, autocratic leadership was seen as less effective in richer countries

with more demanding—colder or hotter—bioclimates (simple slope r = –.54, n = 30, p <

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Van de Vliert / AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP WORLDWIDE 53

TABLE 4

Results of Regression Analyses on Autocratic Leadership

Model 1 Model 2

Variable Initial B Final B Initial B Final B

Geoclimate .22 .19

Bioclimate .19 .03

Wealth –.22 –.23 –.21 –.33*

Geoclimate × Wealth .07

Bioclimate × Wealth –.54**

R2 .10 .26**

Adjusted R2 .05 .22**

NOTE: N = 61 cultures. Regression coefficients are unstandardized beta weights.

*p < .05. **p < .01.

3

Autocratic Leadership

Rich

-1

countries

Poor

-2 countries

-2 -1 0 1 2 3

Demanding Bioclimate

Figure 1: Autocratic Leadership as a Joint Function of Demanding Bioclimate and National Wealth

.001) but as more effective in poorer countries with more demanding bioclimates (simple

slope r = .39, n = 31, p < .05).

I conducted five supplementary analyses to check for possible hidden faults in the results.

First, relying on values of tolerance (> .10) and variance inflation factors (< 10), there was no

multicollinearity of the prediction terms. Second, relying on Cook’s distance coefficients (D

ranges from .00 to .43; MD = .02), there were no outliers either. Third, I paid attention to the

confounded nature of relative poverty and communist past. When the nine countries with a

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

54 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

communist past (Parker, 1997, pp. 47-70) were removed or when communist past was statis-

tically controlled for, the pattern of main and interactive effects of bioclimate and wealth did

not change.

Fourth, a series of regression analyses addressed the rival explanation that the results

were produced by a covariate of national wealth—income equality within nations (Gini

index; United Nations Development Programme, 2001, pp. 182-185). Bioclimate (∆R2 =

.03, n = 51, ns), income equality (∆R2 = .00, ns), and the bioclimate-by-equality interaction

(∆R2 = .18, p < .01) accounted for 21% of the variance in the perceived effectiveness of auto-

cratic leadership. Autocratic organizational leadership was seen as less effective in countries

with more demanding—colder or hotter—climates and more income equality (r = –.38, n =

34, p < .05) but as more effective in countries with more demanding climates and less income

equality (r = .48, n = 17, p < .05).

Further analyses using bioclimate, wealth, and income equality in the first step and the

two-way bioclimatic interaction terms in the second and third steps showed that the

bioclimate-by-wealth interaction (∆R2 = .17, p < .01) and the bioclimate-by-equality inter-

action (∆R2 = .16, p < .01) shared 11% of the variance in the endorsement of autocratic lead-

ership and had unique contributions as well (bioclimate-by-wealth ∆R2 = .06, p < .05;

bioclimate-by-equality ∆R2 = .05, p < .07). The additional interaction effects of wealth-by-

equality and climate-by-wealth-by-equality did not reach significance. These results are in

line with the theoretical point of departure that greater climatic demands matched by the

omnipresence of wealth-based climatic resources make autocratic leadership less effective,

whereas greater climatic demands unmatched by the omnipresence of wealth-based climatic

resources make autocratic leadership more effective.

Last but not least, if the bioclimate-by-wealth explanation rests on solid grounds, it

should hold especially true for the 49 societies in the northern hemisphere, which have more

demanding bioclimates than the 12 societies in the southern hemisphere (M = 1,766 vs. M =

988; SD = 1,053 vs. SD = 387). To reduce the impact of the underrepresentation of southern

hemisphere societies, each society’s contribution to the regression equation was weighted

(wnorth = 1; wsouth = 4). Together, the three predictors (bioclimate, wealth, and hemisphere), the

three two-way interactions, and the three-way interaction accounted for 36% of the country-

level variance in the perceived effectiveness of autocratic leadership. Most important, hemi-

sphere had a strong main effect (∆R2 = .15, = 0.86, p < .001) that was qualified by the three-

way interaction of bioclimate, wealth, and hemisphere (∆R2 = .05, Β = –1.00, p < .05). Visual

inspection of the plots revealed that the bioclimate-by-wealth explanation did hold espe-

cially true for the perceived effectiveness of autocratic leadership in northern hemisphere

organizations.

DISCUSSION

PRELIMINARY NOTES ON CLIMATE-LEADERSHIP LINKS

The relationship between climate and leadership culture is a neglected, controversial, and

complicated topic. Its neglect is apparent from the absence of studies of leadership and man-

agerial behavior in an interdisciplinary listing of 3,307 publications about thermal weather

effects and climatic effects on individual, social, and economic behavior (Parker, 1995). This

undoubtedly reflects the complexity of the country-level connections between climate and

cultural leadership syndromes. Climatic effects on leadership culture, if any, are long-term

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Van de Vliert / AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP WORLDWIDE 55

effects that are difficult to trace accurately, with the consequence that unknown alternative

explanations of these effects cannot be excluded convincingly. Indeed, the observed inter-

active effect of demanding climate and national wealth on the perceived effectiveness of

autocratic leadership in no way proves that the bioclimate-by-wealth composite causes the

endorsement of autocratic leadership in organizational settings. What claims, then, can be

made on the basis of the theoretical and empirical study reported here?

CONCLUDING CLAIMS OR FOLLOWING QUESTIONS?

My first claim is that the country-level endorsement and adoption of autocratic leadership

in organizations does not happen by chance. The systematic and robust nature of differences

in power distance (Hofstede, 2001; House et al., 2004), aversion to participative and

delegative leadership (Van de Vliert & Smith, 2004), and importance of autocratic leadership

skills (this study) leads me to believe that there must be a reason for this pattern of findings.

Indeed, it is implausible that autocratic leadership in organizations has a kind of ecological

niche in richer countries with less demanding bioclimates (e.g., Hong Kong and Qatar) and

in poorer countries with more demanding bioclimates (e.g., Georgia and Poland) for no

reason other than sheer coincidence.

My second claim is that to avoid tautological reasoning, meaningful relations between

national culture and organizational leadership culture (e.g., Brodbeck et al., 2000; Dorfman

et al., 2004; House et al., 1999; House et al., 2004; Schmidt & Yeh, 1992; Shaw, 1990; Wong

& Birnbaum-More, 1994) should be used to describe rather than explain cross-national dif-

ferences in organizational leadership (cf., Hofstede, 2001, p. 388). The paragraph on the

construct validity of the dependent variable showed that cultural power distance correctly

predicts the appreciation of autocratic leadership, but predicted variance is not the same as

explained variance. Correctly predicted variance provides a framework for characterizing

observations, such as culture-leadership links; only theory supplies the explanation of the

observations (Van de Vliert, 1997, pp. 19-23; Whetten, 1989). As a consequence, instead of

answering a question, the second claim prompts a further question: What theory can explain

the pattern of characterizations of autocratic leadership in terms of bioclimate and wealth?

My third claim is that if bioclimate and socioeconomic development do drive cross-

national differences in the endorsement of autocratic leadership in organizations, they do so

in concert. This interaction effect rejects simplistic explanations of the unfolding world map

of leadership in terms of climate (Hofstede, 2001; Van de Vliert & Van Yperen, 1996), socio-

economic development from agrarian to industrial societies (Nolan & Lenski, 1999), or

socioeconomic regression through communist rule (this study). Instead, the results of the

study just reported seem to support Montesquieu’s (1748) in hindsight visionary model of

how atmospheric climate and national wealth interact to influence human functioning.

My fourth claim is that the climate-by-wealth composite is a viable predictor of organiza-

tional differences in the perceived effectiveness of autocratic leadership around the globe

only if the predictions are based on each country’s deviation from a comfortable temperature

level—bioclimatic cold or heat—and not on each country’s mean temperature level—

geoclimate. The importance of this conclusion should not be underestimated as bioclimate

and geoclimate are potentially confounded variables. Given that the bioclimatic deviations

in winter and summer are larger in countries with colder geoclimates, it is surprising that no

prior study has ever modeled and analyzed bioclimate and geoclimate in parallel (for

research overviews, see Gupta & Hanges, 2004; Parker, 1995, 2000).

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

56 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

My final claim is that mismatches of bioclimatic demands and climatic resources

(demanding/poor) are positively linked to the endorsement of self-centered autocratic lead-

ership, whereas matches of bioclimatic demands and climatic resources (demanding/rich)

have negative links. These findings, represented in Figure 1, seem to fit in with the accumu-

lating evidence that bioclimate and wealth operate as double-edged swords. To date, the

“egoistic” impact of bioclimate-wealth mismatches and the “altruistic” impact of

bioclimate-wealth matches have been demonstrated for participative leadership (Van de

Vliert & Smith, 2004), delegative leadership (Van de Vliert & Smith, 2004), motives for vol-

unteer work (Van de Vliert, Huang, & Levine, 2004), and competitiveness versus altruism

(Van de Vliert, Huang, & Parker, 2004, Study 2). Although the current study in no way dem-

onstrates that climate and wealth drive autocratic leadership culture, this expanding set of

internally consistent observations makes it less self-evident to continue to interpret the find-

ings in terms of climatic covariation rather than climatic causation. Do descriptive and pre-

dictive matches of bioclimatic demands and climatic resources have explanatory power after

all?

STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES

This investigation was not without inherent strengths and weaknesses as a result of the

methods employed. The strength of contrasting cultural explanation and explanation of cul-

ture came with the weakness of leaving multiple historical, political, institutional, and reli-

gious explanations of autocratic leadership culture out of consideration. The strength of a

large sample of 61 cultures came with the weakness of a conveniently available sample,

offering no conclusive evidence for cross-national generalization. The strength of distin-

guishing between geoclimate and bioclimate was connected with the weakness of leaving

equally basic parameters, such as air movement and humidity, out of consideration. Finally,

the strength of modeling winter and summer temperature extremes came with the weakness

of a restriction of range on the hot side. The winter and summer proportions of the

bioclimatic predictor used show that harsh winters have an overall weight of .68, whereas

harsh summers have an overall weight of .32; this deserves further attention.

IMPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

The wealth-dependent distribution of autocratic leadership construals over the cold, tem-

perate, and hot zones of the earth, together with similar work on sociopsychological func-

tioning (Van de Vliert, Huang, & Levine, 2004; Van de Vliert, Huang, & Parker, 2004; Van

de Vliert & Smith, 2004), points to the viability of bioclimatic theories on global variation in

human behavior. Although the bioclimatic leadership theory in question is descriptive and

predictive rather than explanatory, colleagues with an ecological orientation will no doubt

read it as providing

a superior strategy for understanding the behavior of individuals and the evolution of cultural

forms because it adopts an etic, scientific approach with a solid starting point in invariant laws of

nature and the relationship among nature, human subsistence techniques, and the adaptation of

societal and psychological characteristics to these exigencies. (Gabrenya, 1999, pp. 339-340)

If the bioclimatic leadership theory survives further replication studies, it will provide a

set of new insights with important theoretical and practical implications. Scholars are chal-

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Van de Vliert / AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP WORLDWIDE 57

lenged to upgrade the bioclimatic propositions from a descriptive and predictive theory to an

explanatory theory, to investigate whether changes in national wealth produce changes in

leadership culture, to contextualize lower level theories of leadership construals and leader

behavior, and to investigate the generalizability of the leadership theory to a larger set of

management practices. International human resource managers and interventionists can no

longer take it for granted that autocratic and democratic leadership approaches are equally

malleable in any direction anywhere. Instead, organization experts might have to come to

grips with different climate-by-wealth niches of leadership culture around the globe.

REFERENCES

Berry, J. W. (1997). An ecocultural approach to the study of cross-cultural industrial/organizational psychology. In

P. C. Earley & M. Erez (Eds.), New perspectives on international industrial/organizational psychology (pp. 130-

147). San Francisco: New Lexington.

Bibby, G. (1965). Four thousand years ago. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, UK: Penguin.

Brodbeck, F. C., Frese, M., Akerblom, S., Audia, G., Bakacsi, G., Bendova, H., et al. (2000). Cultural variation of

leadership prototypes across 22 European countries. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology,

73, 1-29.

Burroughs, W. J. (1997). Does the weather really matter? The social implications of climatic change. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

Carl, D., Gupta, V., & Javidan, M. (2004). Power distance. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, &

V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 513-563). Thou-

sand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Den Hartog, D. N., House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Ruiz-Quintanilla, S. A., Dorfman, P. W., Abdalla, I. A., et al. (1999).

Culturally-specific and cross-culturally generalizable implicit leadership theories: Are attributes of charismatic

leadership theories universally endorsed? The Leadership Quarterly, 10, 219-256.

Dorfman, P. W. (1996). International and cross-cultural leadership. In B. J. Punnett & O. Shenkar (Eds.), Handbook

for international management research (pp. 267-349). Cambridge, MA: Blackwell.

Dorfman, P. W., Hanges, P. J., & Brodbeck, F. C. (2004). Leadership and cultural variation: The identification of cul-

turally endorsed leadership profiles. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.),

Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 669-719). Thousand Oaks, CA:

Sage.

Duncan, R. B. (1972). Characteristics of organizational environments and perceived environmental uncertainty.

Administrative Science Quarterly, 17, 313-327.

Gabrenya, W. K., Jr. (1999). Psychological anthropology and the ‘levels of analysis’problem: We married the wrong

cousin. In J.- C. Lasry, J. G. Adair, & K. L. Dion (Eds.), Latest contributions to cross-cultural psychology (pp.

333-351). Lisse, the Netherlands: Swets & Zeitlinger.

Gerstner, C. R., & Day, D. V. (1994). Cross-cultural comparison of leadership prototypes. The Leadership Quar-

terly, 5, 121-134.

Gupta, V., & Hanges, P. J. (2004). Regional and climate clustering of societal cultures. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges,

M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62

societies (pp. 178-218). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hanges, P. J., & Dickson, M. W. (2004). The development and validation of the GLOBE culture and leadership

scales. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V. Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and orga-

nizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 122-151). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across

cultures. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

House, R. J., & Hanges, P. J. (2004). Research design. In R. J. House, P. J. Hanges, M. Javidan, P. W. Dorfman, & V.

Gupta (Eds.), Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies (pp. 95-101). Thousand

Oaks, CA: Sage.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (Eds.). (2004). Culture, leadership, and organi-

zations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Ruiz-Quintanilla, S. A., Dorfman, P. W., Javidan, M., Dickson, M., et al. (1999). Cultural

influences on leadership and organizations: Project GLOBE. Advances in Global Leadership, 1, 171-233.

Karatnycky, A. (2001). Freedom in the world: The annual survey of political rights and civil liberties 2000-2001.

New York: Freedom House.

Leana, C. R. (1987). Power relinquishment versus power sharing: Theoretical clarification and empirical compari-

son of delegation and participation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 228-233.

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

58 JOURNAL OF CROSS-CULTURAL PSYCHOLOGY

Lenski, G. (1966). Power and privilege. New York: McGraw-Hill.

McClelland, D. C. (1961). The achieving society. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand.

Mintzberg, H. (1979). The structuring of organizations: A synthesis of the research. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice

Hall.

Montesquieu, C. d. S. (1748). L’esprit des lois [The spirit of the laws] (Trans. A. M. Cohler, B. C. Miller, & H. S.

Stone). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Muczyk, J. P., & Reimann, B. C. (1987). The case for directive leadership. Academy of Management Executive, 1,

301-311.

Nolan, P., & Lenski, G. (1999). Human societies: An introduction to macrosociology (8th ed.). New York: McGraw-

Hill.

Parker, P. M. (1995). Climatic effects on individual, social, and economic behavior: A physioeconomic review of

research across disciplines. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Parker, P. M. (1997). National cultures of the world: A statistical reference. Westport, CT: Greenwood.

Parker, P. M. (2000). Physioeconomics: The basis for long-run economic growth. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Parsons, K. C. (1993). Human thermal environments: The effects of hot, moderate and cold environments on human

health, comfort and performance. London: Taylor & Francis.

Peterson, M. F., & Smith, P. B. (1997). Does national culture or ambient temperature explain cross-national differ-

ences in role stress? No sweat! Academy of Management Journal, 40, 930-946.

Sachs, J. (2000). Notes on a new sociology of economic development. In L. E. Harrison & S. P. Huntington (Eds.),

Culture matters: How values shape human progress (pp. 29-43). New York: Basic Books.

Sagie, A., & Koslowsky, M. (2000). Participation and empowerment in organizations: Modeling, effectiveness, and

applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schmidt, S. M., & Yeh, R. S. (1992). The structure of leader influence: A cross-national comparison. Journal of

Cross-Cultural Psychology, 23, 251-264.

Scholander, P. F., Hock, R., Walters, V., Johnson, F., & Irving, L. (1950). Heat regulation in some arctic and tropical

mammals and birds. Biological Bulletin, 99, 237-258.

Service, E. (1975). Origins of the state and civilizations: The process of cultural evolution. New York: Norton.

Shaw, J. B. (1990). A cognitive categorization model for the study of intercultural management. Academy of Man-

agement Review, 15, 626-645.

Smith, P. B. (2004). Acquiescent response bias as an aspect of cultural communication style. Journal of Cross-

Cultural Psychology, 35, 50-61.

Smith, P. B., Misumi, J., Tayeb, M. H., Peterson, M. F., & Bond, M. H. (1989). On the generality of leadership style

measures across cultures. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 62, 97-109.

Smith, P. B., Peterson, M. F., Schwartz, S. H., Ahmad, A. H., Akande, D., Andersen, J. A., et al. (2002). Cultural

values, sources of guidance, and their relevance to managerial behavior: A 47-nation study. Journal of Cross-

Cultural Psychology, 33, 188-208.

Smith, P. B., Peterson, M. F., & Misumi, J. (1994). Event management and work team effectiveness in Japan, Britain

and the U.S.A. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 67(4), 33-43.

Triandis, H. C. (1973). Work and nonwork: Intercultural perspectives. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.), Work and nonwork

in the year 2001 (pp. 29-52). Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

United Nations Development Programme. (2001). Human development report 2001. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Van de Vliert, E. (1997). Complex interpersonal conflict behaviour: Theoretical frontiers. Hove, UK: Psychology

Press.

Van de Vliert, E. (2003). Thermoclimate, culture, and poverty as country-level roots of workers’ wages. Journal of

International Business Studies, 34, 40-52.

Van de Vliert, E., Huang, X., & Levine, R. V. (2004). National wealth and thermal climate as predictors of motives

for volunteer work. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 35, 62-73.

Van de Vliert, E., Huang, X., & Parker, P. M. (2004). Do colder and hotter climates make richer societies more but

poorer societies less happy and altruistic? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24, 17-30.

Van de Vliert, E., Schwartz, S. H., Huismans, S. E., Hofstede, G., & Daan, S. (1999). Temperature, cultural mascu-

linity, and domestic political violence: A cross-national study. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30, 291-

314.

Van de Vliert, E., & Smith, P. B. (2004). Leader reliance on subordinates across nations that differ in development

and climate. The Leadership Quarterly, 15, 381-403.

Van de Vliert, E., & Van Yperen, N. W. (1996). Why cross-national differences in role overload? Don’t overlook

ambient temperature. Academy of Management Journal, 39, 986-1004.

Wheeler, R. H. (1946). Climate and human behavior. In P. L. Harriman (Ed.), Encyclopedia of psychology (pp. 78-

86). New York: Philosophical Library.

Whetten, D. A. (1989). What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 14, 490-495.

Williams, L. K., Whyte, W. F., & Green, C. S. (1966). Do cultural differences affect workers’ attitudes? Industrial

Relations, 5, 105-117.

Wong, G. Y. Y., & Birnbaum-More, P. H. (1994). Culture, context and structure: A test on Hong Kong banks. Organi-

zation Studies, 15, 99-123.

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Van de Vliert / AUTOCRATIC LEADERSHIP WORLDWIDE 59

Evert Van de Vliert is a professor of organizational and applied social psychology at the University of

Groningen in the Netherlands. He has published more than 200 articles in Academy of Management Jour-

nal, Academy of Management Review, Journal of Applied Psychology, Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, and so forth. In 2005, he received the Lifetime Achievement Award of the International Associa-

tion for Conflict Management.

Downloaded from http://jcc.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 11, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

You might also like

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Science 4 - 4th QUARTER Week 3Document14 pagesScience 4 - 4th QUARTER Week 3Khim CalusinNo ratings yet

- Vdoc - Pub Northern BushcraftDocument280 pagesVdoc - Pub Northern BushcraftO Tolga CndrNo ratings yet

- Dạng Câu Hỏi Matching Headings Trong IELTS ReadingDocument20 pagesDạng Câu Hỏi Matching Headings Trong IELTS ReadingPham QuynhNo ratings yet

- All Summer in A Day Workbook AnswersDocument23 pagesAll Summer in A Day Workbook AnswersLekhanana Reddy100% (1)

- Chapter Ii. Literature ReviewDocument23 pagesChapter Ii. Literature ReviewGumilang BreakerNo ratings yet

- Chapter Ii. Literature ReviewDocument23 pagesChapter Ii. Literature ReviewGumilang BreakerNo ratings yet

- 05.creativity and Innovation Leadership Traits - Completed - 2Document22 pages05.creativity and Innovation Leadership Traits - Completed - 2Gumilang BreakerNo ratings yet

- Dalglishand Millerbook 1 at 100Document95 pagesDalglishand Millerbook 1 at 100Gumilang BreakerNo ratings yet

- The Qualitative Content Analysis: Journal of Advanced Nursing May 2008Document11 pagesThe Qualitative Content Analysis: Journal of Advanced Nursing May 2008Gumilang BreakerNo ratings yet

- Personality Structure and Measurement II: The Determination and Utility of Trait ModalityDocument16 pagesPersonality Structure and Measurement II: The Determination and Utility of Trait ModalityGumilang BreakerNo ratings yet

- Essay On LeadershipDocument7 pagesEssay On LeadershipGumilang BreakerNo ratings yet

- Name: Gumilang Cahyo Bawono S. NUMBER: 150203103Document1 pageName: Gumilang Cahyo Bawono S. NUMBER: 150203103Gumilang BreakerNo ratings yet

- The Use of Literary Works in An EFL Class: Minoo AlemiDocument4 pagesThe Use of Literary Works in An EFL Class: Minoo AlemiGumilang BreakerNo ratings yet

- Write A Report For A University Lecturer Describing The Information Shown. Write at Least 150 Words. (Sample, Band 9)Document2 pagesWrite A Report For A University Lecturer Describing The Information Shown. Write at Least 150 Words. (Sample, Band 9)Nguyễn Phương NgọcNo ratings yet

- Vegetation FAODocument12 pagesVegetation FAOAlbanNo ratings yet

- BR11 - Semester 1 - KeyDocument6 pagesBR11 - Semester 1 - KeyThỉ ThỉNo ratings yet

- AP - Ch. 2 Global Air Pollution Issues PDFDocument47 pagesAP - Ch. 2 Global Air Pollution Issues PDFmuhammad bilalNo ratings yet

- Umbrella (Feat. Jay-Z) : RihannaDocument2 pagesUmbrella (Feat. Jay-Z) : RihannaFarleyson MatosNo ratings yet

- Allemailsstatus 1Document65 pagesAllemailsstatus 1sin.som2022No ratings yet

- DRRR FinalsDocument22 pagesDRRR Finalsdenisecatubag15No ratings yet

- Research Topic Ni LouisDocument2 pagesResearch Topic Ni LouisJ. RaphNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan: Doodle Town, Level 2, Unit 9: Rainy DayDocument4 pagesLesson Plan: Doodle Town, Level 2, Unit 9: Rainy DayMayeNo ratings yet

- PDA Request LetterDocument1 pagePDA Request LetterClickon DetroitNo ratings yet

- Bài tập Anh lớp 9 HKIIDocument22 pagesBài tập Anh lớp 9 HKIIChưa Đặt TênNo ratings yet

- Remedial Geography Model Exam-1Document10 pagesRemedial Geography Model Exam-1dagem tesfaye100% (2)

- Steel Pro SeriesDocument8 pagesSteel Pro SeriesChrisjlcox CoxNo ratings yet

- The Origin of Cianjur: A Tale From West JavaDocument3 pagesThe Origin of Cianjur: A Tale From West Javaaisya azistaNo ratings yet

- Scorpions: Absolut Live The Skyline Bremerhaven, Germany 24/08/96Document3 pagesScorpions: Absolut Live The Skyline Bremerhaven, Germany 24/08/96Sergio Arroyo CarrascoNo ratings yet

- AupdDocument13 pagesAupdSuresh RajNo ratings yet

- Application of ARIMAX ModelDocument5 pagesApplication of ARIMAX ModelAgus Setiansyah Idris ShalehNo ratings yet

- Impersonal Passive PracticeDocument1 pageImpersonal Passive PracticeAnnaNo ratings yet

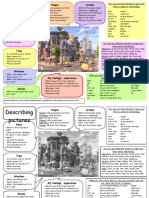

- Describing Pictures: People ActionsDocument2 pagesDescribing Pictures: People ActionsАлина ЖдановаNo ratings yet

- Science-8 Pagasa On Duty: Typhoons in The Philippines Can Occur Any Time of The Year, With TheDocument3 pagesScience-8 Pagasa On Duty: Typhoons in The Philippines Can Occur Any Time of The Year, With TheLannayah coNo ratings yet

- What Is AntarcticaDocument4 pagesWhat Is AntarcticaEzzie DoroNo ratings yet

- Bentech - Retractable Glass Roof A4 - English PDFDocument8 pagesBentech - Retractable Glass Roof A4 - English PDFAnonymous FPTyqHQqeONo ratings yet

- Answer Key Workbook 2: Unit 1 Unit 2Document7 pagesAnswer Key Workbook 2: Unit 1 Unit 2yash patelNo ratings yet

- Southwire - Cable Design - May 2020 - Water BlockingDocument5 pagesSouthwire - Cable Design - May 2020 - Water BlockingAli NaderianNo ratings yet

- Weberend OCRDocument2 pagesWeberend OCRaNo ratings yet

- Qurban Ali, Bridging - ES5 AssignmentDocument14 pagesQurban Ali, Bridging - ES5 AssignmentKingNo ratings yet