Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Cases For Cyber Libel

Uploaded by

MikMik UyOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Cases For Cyber Libel

Uploaded by

MikMik UyCopyright:

Available Formats

Cases for Cyber Libel

1. Disini v. Secretary of Justice (G.R. 203335, 11 February 2014).

Libel is not a constitutionally protected speech. The Cybercrime Prevention

Act of 2012 does not really define cyber libel. It penalizes libel, as defined

under the Revised Penal Code, but imposes a higher penalty because of the

use of information and communication technologies. In Disini, the SC

explained this qualifying circumstance arises from the fact that in “using the

technology in question, the offender often evades identification and is able to

reach far more victims or cause greater harm.”

The elements of libel are the allegation of a discreditable act or condition

concerning another; publication of the charge; identity of the person

defamed, and existence of malice.

As to the first requirement, the allegation must be a malicious imputation of a

crime or of a vice or defect, real or imaginary, or any act, omission, condition,

status or circumstance tending to cause the dishonor, discredit or contempt

of a natural or juridical person or to blacken the memory of one who is dead.

For cyber libel in particular, the publication requirement is satisfied when

the allegation is made publicly through the use of information and

communication technologies.

For the third requisite, it is not necessary that the person defamed is named.

If the totality of the publication makes it possible to determine who the

defamed person is, then this element is also satisfied. Finally, malice exists

when the offender makes the defamatory statement with the knowledge that

it is false or with reckless disregard of whether it was false or not.

2. Bonifacio v. RTC Makati City (Venue of a cyber libel case)

However, for cyber libel, the place where the defamatory article was printed

and first published is impossible to ascertain. It also cannot be where the

defamatory online article was first accessed. In Bonifacio v. RTC Makati City,

the SC said if it allows cyber libel to be filed where the article is first accessed,

the author of the defamatory article may be sued anywhere in the

Philippines. The private complainant can just allege that he accessed the

defamatory online article in a far-flung place. For instance, a blogger in

Manila who posts a defamatory article may then be sued in Ilocos Sur, where

the offended party allegedly first accessed the article. To prevent this

chaotic situation, the High Court effectively limited the venue to the

place where the complainant actually resides at the time of the

commission of the offense.

You might also like

- Grave Oral DefamationDocument3 pagesGrave Oral DefamationAngel CabanNo ratings yet

- Derivative Suit, Validity of The Election of Board of DirectorsDocument13 pagesDerivative Suit, Validity of The Election of Board of DirectorsRommel TottocNo ratings yet

- Civ Pro Cases.1Document5 pagesCiv Pro Cases.1jp_gucksNo ratings yet

- Roberto Otero v. Roger Tan (Rule 9)Document1 pageRoberto Otero v. Roger Tan (Rule 9)ChiiNo ratings yet

- Dog Case ComplaintDocument4 pagesDog Case ComplaintEllen DebutonNo ratings yet

- Quiambao v. CADocument6 pagesQuiambao v. CAclandestine2684No ratings yet

- Qdoc - Tips Counter Affidavit BP 22Document4 pagesQdoc - Tips Counter Affidavit BP 22joey celesparaNo ratings yet

- Speluncean Explorers CaseDocument8 pagesSpeluncean Explorers CaseJohnelle Ashley Baldoza TorresNo ratings yet

- FINALS Summary of DecisionDocument15 pagesFINALS Summary of DecisionKirk Patrick LopezNo ratings yet

- Sample ReplevinDocument3 pagesSample ReplevinAnsley SilvestreNo ratings yet

- Guilty Falsification of Public DocumentDocument8 pagesGuilty Falsification of Public DocumentAnonymous 4IOzjRIB1No ratings yet

- Serafin Tijam, Et Al. Vs - Magdaleno Sibonghanoy Alias Gavino Sibonghanoy and Lucia BAGUIO (CASE DIGEST) G.R. No. L-21450 - April 15, 1968Document16 pagesSerafin Tijam, Et Al. Vs - Magdaleno Sibonghanoy Alias Gavino Sibonghanoy and Lucia BAGUIO (CASE DIGEST) G.R. No. L-21450 - April 15, 1968Mark Kevin MartinNo ratings yet

- Certification/ Verification of PleadingsDocument3 pagesCertification/ Verification of PleadingsMaria Margaret MacasaetNo ratings yet

- Philippine Collection CaseDocument3 pagesPhilippine Collection CaseLaika HernandezNo ratings yet

- Complaint For Foreclosure of Real Estate MortgageaaDocument3 pagesComplaint For Foreclosure of Real Estate MortgageaaEmilio Ong SorianoNo ratings yet

- Verification 2020Document1 pageVerification 2020Sig G. MiNo ratings yet

- Aid Ofadmin Law Cases Other Powers Secretary of Justice Vs Judge Lantion-1Document2 pagesAid Ofadmin Law Cases Other Powers Secretary of Justice Vs Judge Lantion-1Reb CustodioNo ratings yet

- Complaint Affidavit Kidnapping and Serious Illegal Detention With Affidavits and AnnexesDocument10 pagesComplaint Affidavit Kidnapping and Serious Illegal Detention With Affidavits and AnnexesElizabeth Jade D. CalaorNo ratings yet

- FORM NO. 92 Notarial Will - Spouse and ChildrenDocument2 pagesFORM NO. 92 Notarial Will - Spouse and ChildrenAlexandrius Van VailocesNo ratings yet

- Motion To DismissDocument7 pagesMotion To DismissCarljunitaNo ratings yet

- Donor's Tax-2Document36 pagesDonor's Tax-2Razel Mhin MendozaNo ratings yet

- Nsurance ODE: Bartolome Puzon, JR., G.R. No. 167567, September 22, 2011)Document56 pagesNsurance ODE: Bartolome Puzon, JR., G.R. No. 167567, September 22, 2011)kate fielNo ratings yet

- Banking Laws Course Syllabus AY20-21Document3 pagesBanking Laws Course Syllabus AY20-21Paolo SueltoNo ratings yet

- 1 - Answer - BT v. EDDocument10 pages1 - Answer - BT v. EDdulnuan jerusalemNo ratings yet

- Joint Affidavit of CohabitationDocument2 pagesJoint Affidavit of CohabitationEds GalinatoNo ratings yet

- DIGESTDocument2 pagesDIGESTKherry LoNo ratings yet

- Occena Vs IcaminaDocument2 pagesOccena Vs IcaminaRian Lee TiangcoNo ratings yet

- Bar QSDocument11 pagesBar QSRikka ReyesNo ratings yet

- 06 Mock - Verbal (2) - Class Sinagtala 2023Document9 pages06 Mock - Verbal (2) - Class Sinagtala 2023Elixer De Asis VelascoNo ratings yet

- PERSONAL COLLECTION DIRECT SELLING, INC., v. TERESITA L. CARANDANGDocument33 pagesPERSONAL COLLECTION DIRECT SELLING, INC., v. TERESITA L. CARANDANGgirlNo ratings yet

- Deed of Absolute SaleDocument2 pagesDeed of Absolute SalealyNo ratings yet

- Civpro - AnswerDocument5 pagesCivpro - AnswerVictor FernandezNo ratings yet

- Pioneer vs. GuadizDocument9 pagesPioneer vs. GuadizZaira Gem GonzalesNo ratings yet

- TAXATION OF FOREIGN INDIVIDUALS IN THE PHILIPPINESDocument25 pagesTAXATION OF FOREIGN INDIVIDUALS IN THE PHILIPPINESHailin QuintosNo ratings yet

- 46 Petition For Review RTC CADocument18 pages46 Petition For Review RTC CAChristine Joy PrestozaNo ratings yet

- TAXATION LAW REVIEW TopicsDocument13 pagesTAXATION LAW REVIEW TopicsKimberly RamosNo ratings yet

- Dacasin v. DacasinDocument3 pagesDacasin v. DacasinChristiane Marie BajadaNo ratings yet

- 80389-2000-The 2000 Bail Bond GuideDocument110 pages80389-2000-The 2000 Bail Bond GuidePau SaulNo ratings yet

- Public International Law: 2008 LEI Notes inDocument70 pagesPublic International Law: 2008 LEI Notes inArgao Station FinestNo ratings yet

- FORM NO. 2. Acknowledgement of Instrument Consisting of Two or More PagesDocument1 pageFORM NO. 2. Acknowledgement of Instrument Consisting of Two or More PagesXirkul TupasNo ratings yet

- YASUDA Vs CADocument3 pagesYASUDA Vs CARussellNo ratings yet

- ChanelleDocument3 pagesChanelleBaldr BringasNo ratings yet

- MemorandumDocument3 pagesMemorandumBurn-Cindy AbadNo ratings yet

- ComplaintDocument5 pagesComplaintAllyza Mhay RendonNo ratings yet

- Section 401-402Document8 pagesSection 401-402Rigel Kent Tugade100% (1)

- Ombudsman case against Customs officerDocument2 pagesOmbudsman case against Customs officerHalmen ValdezNo ratings yet

- Court Rules First Jeopardy Attached in Dismissed CaseDocument137 pagesCourt Rules First Jeopardy Attached in Dismissed CaseGiane EndayaNo ratings yet

- Versus-: Republic of The Philippines 11 Judicial Region Branch - CityDocument2 pagesVersus-: Republic of The Philippines 11 Judicial Region Branch - CityRob ClosasNo ratings yet

- People vs. Ramos (Full Text, Word Version)Document13 pagesPeople vs. Ramos (Full Text, Word Version)Emir MendozaNo ratings yet

- 11 - Petition For Declaration of AbsenceDocument1 page11 - Petition For Declaration of AbsenceJohn AysonNo ratings yet

- PALS EvidenceDocument37 pagesPALS EvidenceIrish PDNo ratings yet

- 972 Contreras Vs de LeonDocument1 page972 Contreras Vs de Leonerica pejiNo ratings yet

- Criminal ComplaintDocument5 pagesCriminal Complaintching113No ratings yet

- Republic v. Sali, G.R. No. 206023, April 3, 2017Document3 pagesRepublic v. Sali, G.R. No. 206023, April 3, 2017Dah Rin Cavan100% (1)

- Affidavit ConcubinageDocument1 pageAffidavit ConcubinageAzrael Cassiel0% (1)

- Outreach Cyber LibelDocument2 pagesOutreach Cyber Libelolbes maricelNo ratings yet

- Cyber LibelDocument2 pagesCyber LibelDon Astorga DehaycoNo ratings yet

- Understanding Cyber Libel Under the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012Document3 pagesUnderstanding Cyber Libel Under the Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012Israel Forto100% (1)

- Understanding Cyber Libel and Its ProsecutionDocument2 pagesUnderstanding Cyber Libel and Its ProsecutionNyl Aner100% (2)

- What Is Cyber LibelDocument8 pagesWhat Is Cyber LibelSam B. PinedaNo ratings yet

- Pre Fi NotesDocument35 pagesPre Fi NotesMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Single Entry ApproachDocument3 pagesSingle Entry Approachabc12342No ratings yet

- 2019legislation - Revised Corporation Code Comparative Matrix PDFDocument120 pages2019legislation - Revised Corporation Code Comparative Matrix PDFlancekim21No ratings yet

- Unitary V FedDocument1 pageUnitary V FedMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Cases Under IPL TrademarksDocument8 pagesCases Under IPL TrademarksMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Obligations 1. Different Kinds of ObligationsDocument17 pagesObligations 1. Different Kinds of ObligationsMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Different Kinds of Obligation: Pure and ConditionalDocument25 pagesDifferent Kinds of Obligation: Pure and ConditionalMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Oblicon Pre-Mid Notes PDFDocument13 pagesOblicon Pre-Mid Notes PDFAthina Maricar CabaseNo ratings yet

- Contract Form RequirementsDocument50 pagesContract Form RequirementsMikMik Uy0% (1)

- IBL Finals Reviewer 404 2016 2017 PDFDocument47 pagesIBL Finals Reviewer 404 2016 2017 PDFMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Separate AcknowledgementDocument1 pageSeparate AcknowledgementMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Return-to-Work Establishment Report FormDocument4 pagesReturn-to-Work Establishment Report FormBhianca Ruth MauricioNo ratings yet

- Affixing and Acceptance of Electronic Signatures PDFDocument4 pagesAffixing and Acceptance of Electronic Signatures PDFToto OngNo ratings yet

- Katarungang Pambarangay Form No. 2 Appointment as Lupon MemberDocument1 pageKatarungang Pambarangay Form No. 2 Appointment as Lupon Memberdenvergamlosen100% (1)

- Affirmative Defense Based On Discharge in BankruptcyDocument1 pageAffirmative Defense Based On Discharge in Bankruptcycpbello97No ratings yet

- Affirmative Defense Based On The Statute of LimitationsDocument1 pageAffirmative Defense Based On The Statute of LimitationsMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Self-Adjudication: (Name of Deceased Depositor)Document1 pageAffidavit of Self-Adjudication: (Name of Deceased Depositor)Eahl SerrotNo ratings yet

- CRIMINAL PeopleV Gallanosa, JR UYDocument1 pageCRIMINAL PeopleV Gallanosa, JR UYMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Affidavit of Adjudication by Sole Heir of Estate of Deceased Person With Simultaneous SaleDocument3 pagesAffidavit of Adjudication by Sole Heir of Estate of Deceased Person With Simultaneous SaleMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Petitioners Vs Vs Respondent: First DivisionDocument11 pagesPetitioners Vs Vs Respondent: First DivisionThereseSunicoNo ratings yet

- Philippines issues COVID-19 privacy guidelinesDocument8 pagesPhilippines issues COVID-19 privacy guidelinesFranchise AlienNo ratings yet

- EffectiveDocument53 pagesEffectiveanneNo ratings yet

- LABOR United Coconut Chemicals, Inc - Vvalmores UYDocument1 pageLABOR United Coconut Chemicals, Inc - Vvalmores UYMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- SampleJudicial+Affidavit 1Document4 pagesSampleJudicial+Affidavit 1Thesa Putungan-Salcedo100% (1)

- Philippines vs Juan Richard Tionloc y Marquez Rape CaseDocument1 pagePhilippines vs Juan Richard Tionloc y Marquez Rape CaseMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Commercial San Josevozamiz UyDocument1 pageCommercial San Josevozamiz UyMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Political - Villamorvpeople - UyDocument1 pagePolitical - Villamorvpeople - UyMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Remedial - Fcdpawnshopvunionbank - UyDocument1 pageRemedial - Fcdpawnshopvunionbank - UyMikMik UyNo ratings yet

- Judicial Audit Results in DismissalDocument1 pageJudicial Audit Results in DismissalMikMik UyNo ratings yet

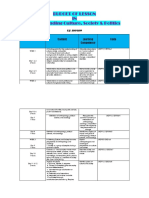

- Table of PenaltiesDocument33 pagesTable of PenaltiesajdgafjsdgaNo ratings yet

- ( ) CLJ Coaching 2012Document29 pages( ) CLJ Coaching 2012Herowin Limlao Eduardo100% (1)

- Lesson 7 - Deviance and ConformityDocument37 pagesLesson 7 - Deviance and ConformityErwil AgbonNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Criminology PPT NewDocument141 pagesIntroduction To Criminology PPT NewYalz MarkuzNo ratings yet

- Reinstating the Death PenaltyDocument2 pagesReinstating the Death PenaltyBrayden SmithNo ratings yet

- Dorado vs. PeopleDocument17 pagesDorado vs. Peopleeunice demaclidNo ratings yet

- (U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictDocument8 pages(U) Daily Activity Report: Marshall DistrictFauquier NowNo ratings yet

- 2020-10-22 CrimFilingsMonthly - WithheadingsDocument579 pages2020-10-22 CrimFilingsMonthly - WithheadingsBR KNo ratings yet

- Social Deviance and Social ControlDocument17 pagesSocial Deviance and Social ControlCharmane Lizette TarcenaNo ratings yet

- Lectures One and Two - Non-Fatal OfffencesDocument21 pagesLectures One and Two - Non-Fatal Offfencesveercasanova0% (1)

- Sentencing Practice PDFDocument14 pagesSentencing Practice PDFamclansNo ratings yet

- Sociology: Paper 2251/01 Paper 1Document6 pagesSociology: Paper 2251/01 Paper 1mstudy123456No ratings yet

- People v. Belbes Case DigestDocument2 pagesPeople v. Belbes Case DigestElla Tho33% (3)

- People - v. - Retubado20180417-1159-1kscjpk PDFDocument11 pagesPeople - v. - Retubado20180417-1159-1kscjpk PDFAdrianNo ratings yet

- Economics of Crime PDFDocument147 pagesEconomics of Crime PDFIvaylo YordanovNo ratings yet

- Anticipatory Bail Plea for Murder CaseDocument2 pagesAnticipatory Bail Plea for Murder CaseBusiness Law Group CUSBNo ratings yet

- How To Live Safely in A Dangerous World - Loren W. ChristensenDocument223 pagesHow To Live Safely in A Dangerous World - Loren W. Christensenkimkanari421175% (4)

- Crime and Deviance OverviewDocument80 pagesCrime and Deviance OverviewPerry EnodolomwanyiNo ratings yet

- (Digest) People v. Oanis, 74 Phil. 257Document2 pages(Digest) People v. Oanis, 74 Phil. 257Joel Pino Mangubat100% (1)

- LEA 6 Comparative Police System PDFDocument1 pageLEA 6 Comparative Police System PDFjalanie camama100% (5)

- Uganda Police Force Annual Crime Report, 2018Document184 pagesUganda Police Force Annual Crime Report, 2018African Centre for Media ExcellenceNo ratings yet

- PERSONNELS-BOARD OF PARDON AND PAROLE Region-11Document5 pagesPERSONNELS-BOARD OF PARDON AND PAROLE Region-11Mike Angelo PateñoNo ratings yet

- I. Chicago Schools of Crimino Logy Maicy BaesDocument36 pagesI. Chicago Schools of Crimino Logy Maicy BaesRach EiLNo ratings yet

- Akayesu - Rape Definition Only International LawDocument2 pagesAkayesu - Rape Definition Only International LawMaria Guila Renee BaldonadoNo ratings yet

- 5 - Chapter 2Document115 pages5 - Chapter 2Tejaswi SaxenaNo ratings yet

- BDS - Captain Regino Den Ocana - PackageDocument44 pagesBDS - Captain Regino Den Ocana - PackageMichael Maningat CapaciaNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law RevDocument12 pagesCriminal Law RevJan Paul CrudaNo ratings yet

- Understanding Culture, Society & PoliticsDocument8 pagesUnderstanding Culture, Society & PoliticsMichelle Ann SabilonaNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Lecture Highlights Key Principles (2019 BarDocument36 pagesCriminal Law Lecture Highlights Key Principles (2019 Baryanice coleen diazNo ratings yet

- CLJ 2 PRELIM EXAM REVIEWDocument8 pagesCLJ 2 PRELIM EXAM REVIEWRee-Ann Escueta BongatoNo ratings yet