Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Sawfly Larvae

Uploaded by

Jhanela Malate0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views1 pageeyeeee

Original Title

eye

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this Documenteyeeee

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

7 views1 pageSawfly Larvae

Uploaded by

Jhanela Malateeyeeee

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 1

Complex eyes can distinguish shapes and

colours. The visual fields of many organisms, especially

predators, involve large areas of binocular vision to improve depth perception. In other organisms,

eyes are located so as to maximise the field of view, such as in rabbits and horses, which

have monocular vision.

The first proto-eyes evolved among animals 600 million years ago about the time of the Cambrian

explosion.[3] The last common ancestor of animals possessed the biochemical toolkit necessary for

vision, and more advanced eyes have evolved in 96% of animal species in six of the

~35[a] main phyla.[1] In most vertebrates and some molluscs, the eye works by allowing light to enter

and project onto a light-sensitive panel of cells, known as the retina, at the rear of the eye. The cone

cells (for colour) and the rod cells (for low-light contrasts) in the retina detect and convert light into

neural signals for vision. The visual signals are then transmitted to the brain via the optic nerve.

Such eyes are typically roughly spherical, filled with a transparent gel-like substance called

the vitreous humour, with a focusing lens and often an iris; the relaxing or tightening of the muscles

around the iris change the size of the pupil, thereby regulating the amount of light that enters the

eye,[4] and reducing aberrations when there is enough light. [5] The eyes of

most cephalopods, fish, amphibians and snakes have fixed lens shapes, and focusing vision is

achieved by telescoping the lens—similar to how a camera focuses.[6]

Compound eyes are found among the arthropods and are composed of many simple facets which,

depending on the details of anatomy, may give either a single pixelated image or multiple images,

per eye. Each sensor has its own lens and photosensitive cell(s). Some eyes have up to 28,000

such sensors, which are arranged hexagonally, and which can give a full 360° field of vision.

Compound eyes are very sensitive to motion. Some arthropods, including many Strepsiptera, have

compound eyes of only a few facets, each with a retina capable of creating an image, creating

vision. With each eye viewing a different thing, a fused image from all the eyes is produced in the

brain, providing very different, high-resolution images.

Possessing detailed hyperspectral colour vision, the Mantis shrimp has been reported to have the

world's most complex colour vision system.[7] Trilobites, which are now extinct, had unique compound

eyes. They used clear calcite crystals to form the lenses of their eyes. In this, they differ from most

other arthropods, which have soft eyes. The number of lenses in such an eye varied; however, some

trilobites had only one, and some had thousands of lenses in one eye.

In contrast to compound eyes, simple eyes are those that have a single lens. For example, jumping

spiders have a large pair of simple eyes with a narrow field of view, supported by an array of other,

smaller eyes for peripheral vision. Some insect larvae, like caterpillars, have a different type of

simple eye (stemmata) which usually provides only a rough image, but (as in sawfly larvae) can

possess resolving powers of 4 degrees of arc, be polarization-sensitive and capable of increasing its

absolute sensitivity at night by a factor of 1,000 or more. [8] Some of the simplest eyes, called ocelli,

can be found in animals like some of the snails, which cannot actually "see" in the normal sense.

They do have photosensitive cells, but no lens and no other means of projecting an image onto

these cells. They can distinguish between light and dark, but no more. This enables snails to keep

out of direct sunlight. In organisms dwelling near deep-sea vents, compound eyes have been

secondarily simplified and adapted to see the infra-red light produced by the hot vents—in this way

the bearers can avoid being boiled alive.[9]

You might also like

- Animal Vision EssayDocument6 pagesAnimal Vision EssayFarrah ZainolNo ratings yet

- Bird VisionDocument13 pagesBird VisionХристинаГулеваNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of The Eye PDFDocument3 pagesAnatomy of The Eye PDFPerry SinNo ratings yet

- Fujilove Magazine May 2020 Issue50Document97 pagesFujilove Magazine May 2020 Issue50Timothy Rosenberg75% (4)

- Service Manual: VK-S214R VK-S214ERDocument57 pagesService Manual: VK-S214R VK-S214ERWuryAgusNo ratings yet

- EyesDocument2 pagesEyesIndahNo ratings yet

- Physics Project: To Study The Optical Lens of A Human EyeDocument14 pagesPhysics Project: To Study The Optical Lens of A Human EyeAkash DhingraNo ratings yet

- Eyes Are: Eye ofDocument8 pagesEyes Are: Eye ofJaisurya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Jump To Navigation Jump To SearchDocument6 pagesJump To Navigation Jump To SearchAljhon DelfinNo ratings yet

- EyesDocument7 pagesEyesopwa fifaNo ratings yet

- ST - Amatiel Technological Institute: Malolos, City BulacanDocument18 pagesST - Amatiel Technological Institute: Malolos, City BulacancherubrockNo ratings yet

- This Article Is About The Organ. For The Human Eye, See - For The Letter, See - For Other Uses, See - "Eyeball", "Eyes", and "Ocular" Redirect Here. For Other Uses, See,, andDocument15 pagesThis Article Is About The Organ. For The Human Eye, See - For The Letter, See - For Other Uses, See - "Eyeball", "Eyes", and "Ocular" Redirect Here. For Other Uses, See,, andMichael FelicianoNo ratings yet

- CSC 620: Image Analysis & Pattern Recognition Assignment 00 Summer-2013Document6 pagesCSC 620: Image Analysis & Pattern Recognition Assignment 00 Summer-2013Joseph KingNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of EyeDocument14 pagesAnatomy of EyeP VenkatesanNo ratings yet

- Animal Form and Function PartDocument3 pagesAnimal Form and Function Partmahreen akramNo ratings yet

- The anatomy and functions of the pupilDocument3 pagesThe anatomy and functions of the pupilJaisurya SharmaNo ratings yet

- Why Do Cats Have Vertical Pupils?: 1. Watch A Video With A Teacher and Answer The Questions BelowDocument5 pagesWhy Do Cats Have Vertical Pupils?: 1. Watch A Video With A Teacher and Answer The Questions BelowBartosz Daniel DębskiNo ratings yet

- Seeing Eye To Eye: Vertebrate Eye Evolution and Adaptive RadiationDocument7 pagesSeeing Eye To Eye: Vertebrate Eye Evolution and Adaptive RadiationAprille Octaviano-AsiloNo ratings yet

- Asvs 04 0267Document7 pagesAsvs 04 0267T KNo ratings yet

- The Eye: (We'll Leave The Lord Sauron Jokes To You.)Document15 pagesThe Eye: (We'll Leave The Lord Sauron Jokes To You.)taurito26No ratings yet

- Bionic Arm Brainport Brain Tongue Vision Light: Digital CameraDocument2 pagesBionic Arm Brainport Brain Tongue Vision Light: Digital CameraGopikrishna NallamothuNo ratings yet

- The Insect World: Being a Popular Account of the Orders of Insects; Together with a Description of the Habits and Economy of Some of the Most Interesting SpeciesFrom EverandThe Insect World: Being a Popular Account of the Orders of Insects; Together with a Description of the Habits and Economy of Some of the Most Interesting SpeciesNo ratings yet

- Biology Eye NotesDocument12 pagesBiology Eye NotesBalakrishnan MarappanNo ratings yet

- Keep Reading To Find Out What These Parts of The Human Eye Do and How They Contribute To Us Being Able To SeeDocument6 pagesKeep Reading To Find Out What These Parts of The Human Eye Do and How They Contribute To Us Being Able To SeeAirlangga kusuma HartoyoNo ratings yet

- Humans, and Other Animals, Are Able To Detect A Range of Stimuli From The External Environment, Some of Which Are Useful For CommunicationDocument13 pagesHumans, and Other Animals, Are Able To Detect A Range of Stimuli From The External Environment, Some of Which Are Useful For CommunicationYouieeeNo ratings yet

- Insect Vision: Zales Promo Code GemstoneDocument11 pagesInsect Vision: Zales Promo Code Gemstonejohn cenaNo ratings yet

- HowDocument8 pagesHowMarie St. LouisNo ratings yet

- What Makes Up An EyeDocument3 pagesWhat Makes Up An EyenandhantammisettyNo ratings yet

- Animal EyesDocument39 pagesAnimal EyesT KNo ratings yet

- 3f228a REPTILESDocument10 pages3f228a REPTILESAndrés González RodríguezNo ratings yet

- The History of EyesDocument1 pageThe History of Eyesthe wolf gaming JDBNo ratings yet

- BLUNT TRAUMA TO THE EYEDocument38 pagesBLUNT TRAUMA TO THE EYEAyu KottenNo ratings yet

- Structure and Function of The Human EyeDocument6 pagesStructure and Function of The Human EyeAljhon DelfinNo ratings yet

- VisibleBody Human Eye Ebook 2017Document15 pagesVisibleBody Human Eye Ebook 2017Sandra RubianoNo ratings yet

- Compound EyeDocument5 pagesCompound EyeWael ElwekelNo ratings yet

- Wildlife Fact File - Animal Behavior - Pgs. 1-10Document20 pagesWildlife Fact File - Animal Behavior - Pgs. 1-10ClearMind84No ratings yet

- Biology of Fishes Fish/Biol 311Document33 pagesBiology of Fishes Fish/Biol 311Vanessa RGNo ratings yet

- Human EyeDocument12 pagesHuman Eyeanu rettiNo ratings yet

- Poo! What IS That Smell?: Everything You Need to Know About the Five SensesFrom EverandPoo! What IS That Smell?: Everything You Need to Know About the Five SensesNo ratings yet

- A Project On " Human Eye": Submitted To-Submitted byDocument13 pagesA Project On " Human Eye": Submitted To-Submitted byaman1990100% (1)

- Evolution of Vertebrate Eyes - How Vision EvolvedDocument14 pagesEvolution of Vertebrate Eyes - How Vision Evolvedlurolu1060No ratings yet

- Sense Organs: Structure of Human EyeDocument8 pagesSense Organs: Structure of Human EyeRanveer SinghNo ratings yet

- Human EyeDocument54 pagesHuman EyeRadu VisanNo ratings yet

- WPR 2Document5 pagesWPR 2ishika mohanNo ratings yet

- Crash Course VisionDocument2 pagesCrash Course VisionReem SleemNo ratings yet

- The Eye: (We'll Leave The Lord Sauron Jokes To You.)Document15 pagesThe Eye: (We'll Leave The Lord Sauron Jokes To You.)ناديه المعمريNo ratings yet

- Safari - 13-Jun-2020 at 5:39 PMDocument1 pageSafari - 13-Jun-2020 at 5:39 PMSantosh J Yadav's FriendNo ratings yet

- Anatomy of EyeDocument11 pagesAnatomy of EyeAbi Nan ThanNo ratings yet

- Vision-Lecture Notes-RskDocument6 pagesVision-Lecture Notes-Rskdevilalshingh9525No ratings yet

- 5 Senses and Their Sense OrgansDocument21 pages5 Senses and Their Sense OrgansViswaNo ratings yet

- Organs of VisionDocument3 pagesOrgans of VisionNarasimha Murthy100% (1)

- The Human EyeDocument21 pagesThe Human EyeMichel ThorupNo ratings yet

- Photochemistry of VisionDocument35 pagesPhotochemistry of VisionHugh Jacobs60% (5)

- UNIT 6 Sensory System Vision AND Perception NOTESDocument12 pagesUNIT 6 Sensory System Vision AND Perception NOTESKristine Nicole FloresNo ratings yet

- Everyday Science NotesDocument46 pagesEveryday Science NotesGul JeeNo ratings yet

- The Physics of Light and Color - Human Vision and Color Perception - Olympus LSDocument14 pagesThe Physics of Light and Color - Human Vision and Color Perception - Olympus LSmarialopezmartinez424No ratings yet

- The Best Place for CSS Aspirants to Learn About the Anatomy and Function of the Human EyeDocument50 pagesThe Best Place for CSS Aspirants to Learn About the Anatomy and Function of the Human EyeWaqas Gul100% (1)

- Compound Eye in InsectDocument8 pagesCompound Eye in InsectAnupam GhoshNo ratings yet

- Structure of Eye !Document11 pagesStructure of Eye !Leonora KadriuNo ratings yet

- Low Vision: Assessment and Educational Needs: A Guide to Teachers and ParentsFrom EverandLow Vision: Assessment and Educational Needs: A Guide to Teachers and ParentsNo ratings yet

- Helping Hands: Acknowledging Support for Maritime ResearchDocument5 pagesHelping Hands: Acknowledging Support for Maritime ResearchJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- How Often to Do Cardio Workouts Based on Your Fitness GoalsDocument3 pagesHow Often to Do Cardio Workouts Based on Your Fitness GoalsJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- How Often to Do Cardio Workouts Based on Your Fitness GoalsDocument3 pagesHow Often to Do Cardio Workouts Based on Your Fitness GoalsJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- When is the Best Time to Book Flights to CaliforniaDocument4 pagesWhen is the Best Time to Book Flights to CaliforniaJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- SDKNBKSJFCNKDSPKVJ FLMVL MFD Kdnfkopdsjgirjng Cdhfgiorehgr Nojcdniofheiog Ncoiudhfgiorhoig NdigojrDocument1 pageSDKNBKSJFCNKDSPKVJ FLMVL MFD Kdnfkopdsjgirjng Cdhfgiorehgr Nojcdniofheiog Ncoiudhfgiorhoig NdigojrJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- How Long Should Your Cardio Workout Be For Best ResultsDocument1 pageHow Long Should Your Cardio Workout Be For Best ResultsJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- How Long Should Your Cardio Workout Be For Best ResultsDocument1 pageHow Long Should Your Cardio Workout Be For Best ResultsJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- SDKNBKSJFCNKDSPKVJ FLMVL MFD Kdnfkopdsjgirjng Cdhfgiorehgr Nojcdniofheiog Ncoiudhfgiorhoig NdigojrDocument1 pageSDKNBKSJFCNKDSPKVJ FLMVL MFD Kdnfkopdsjgirjng Cdhfgiorehgr Nojcdniofheiog Ncoiudhfgiorhoig NdigojrJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- Toxic Effects of CaloriesDocument1 pageToxic Effects of CaloriesJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- Calorie Definition: Candy Bar LettuceDocument1 pageCalorie Definition: Candy Bar LettuceJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- Google LLC Is An AmericanDocument1 pageGoogle LLC Is An AmericanJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- What Is Cardio?: Based On The Findings and Conclusions, The Researchers Forward The Following RecommendationsDocument3 pagesWhat Is Cardio?: Based On The Findings and Conclusions, The Researchers Forward The Following RecommendationsJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- Google LLC Is An AmericanDocument1 pageGoogle LLC Is An AmericanJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- Google LLC Is An AmericanDocument1 pageGoogle LLC Is An AmericanJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- Plants Poisons: Origin of Poison - PlantsDocument4 pagesPlants Poisons: Origin of Poison - PlantsJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- Marketing Mix 4psDocument7 pagesMarketing Mix 4psJhanela MalateNo ratings yet

- Sensors in Monitoring and Control ApplicationsDocument4 pagesSensors in Monitoring and Control ApplicationsKatherine PierceNo ratings yet

- Gafa Helius SG59CAFDocument3 pagesGafa Helius SG59CAFWilson RamírezNo ratings yet

- Quick Guide to Shooting Video with the Panasonic GH4Document71 pagesQuick Guide to Shooting Video with the Panasonic GH4Amr MassoudNo ratings yet

- SZX7 SZ61 SZ51Document15 pagesSZX7 SZ61 SZ51Minh TBB GlobalNo ratings yet

- Draft - Rig Spares - Miscellaneous Stock Items-1Document65 pagesDraft - Rig Spares - Miscellaneous Stock Items-1Project Sales CorpNo ratings yet

- A.P. Shah INSTITUTE of Technology RAI QTN 0101 College LabDocument4 pagesA.P. Shah INSTITUTE of Technology RAI QTN 0101 College LabKate AllenNo ratings yet

- Schmidt Bender Datasheet Gen II XR FFP 5 25x56 PM IIDocument3 pagesSchmidt Bender Datasheet Gen II XR FFP 5 25x56 PM IIJo BanaroNo ratings yet

- Basler Area Scan Cameras VGA to 5MP and Up to 210 FPSDocument6 pagesBasler Area Scan Cameras VGA to 5MP and Up to 210 FPSKUMA1999No ratings yet

- 4K Resolution - WikipediaDocument19 pages4K Resolution - WikipediaAnonymous uwoXOvNo ratings yet

- Solution Manual For Business Analytics Data Analysis Decision Making 6th Edition AlbrightDocument36 pagesSolution Manual For Business Analytics Data Analysis Decision Making 6th Edition Albrightfledconjunct.78pk100% (52)

- Photojournalism-NotesDocument1 pagePhotojournalism-NotesAybukeNo ratings yet

- 2018 Liu, Detection of Citrus Fruit and Tree Trunks in Natural Environments Using ADocument8 pages2018 Liu, Detection of Citrus Fruit and Tree Trunks in Natural Environments Using AShahid Amir LakNo ratings yet

- Harwell Capital - Investor Presentation 2013Document19 pagesHarwell Capital - Investor Presentation 2013hyenadogNo ratings yet

- O I - LT3 - HP3 - User - 02Document14 pagesO I - LT3 - HP3 - User - 02Francisco AvilaNo ratings yet

- Ifixit Fast Fix Proposal RevisedDocument4 pagesIfixit Fast Fix Proposal Revisedapi-643734720No ratings yet

- TECNO CAMON 30 Series Specs Via Revu PhilippinesDocument2 pagesTECNO CAMON 30 Series Specs Via Revu PhilippinesAlora Uy GuerreroNo ratings yet

- TMS Ale-5100 PDFDocument8 pagesTMS Ale-5100 PDFAndrii HorbanNo ratings yet

- To Study The Implementation of Women's Safety Device in Crucial SituationsDocument4 pagesTo Study The Implementation of Women's Safety Device in Crucial SituationsInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Curacha ExaminationDocument6 pagesCuracha ExaminationMaria Anna Curacha Mondragon100% (1)

- CCTVDocument16 pagesCCTVmjcareNo ratings yet

- Gopro Case Study - MKT 3320 SmallDocument8 pagesGopro Case Study - MKT 3320 Smallapi-535077408No ratings yet

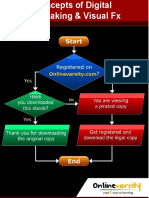

- Concepts of Digital Filmmaking and Visual FX - INTLDocument164 pagesConcepts of Digital Filmmaking and Visual FX - INTLBa Cay TrucNo ratings yet

- Amateur Photographer-31 January 2023Document102 pagesAmateur Photographer-31 January 2023Andrei LucianNo ratings yet

- What Is Cinematic?: All The Techniques and Methods of Filmmaking That We Use To Add Layers of Meaning To The ContentDocument36 pagesWhat Is Cinematic?: All The Techniques and Methods of Filmmaking That We Use To Add Layers of Meaning To The ContentCarlos Daniel Bul-anonNo ratings yet

- Mirrors and Lenses ReviewerDocument9 pagesMirrors and Lenses ReviewerVannie MonderoNo ratings yet

- Requesting InfoDocument12 pagesRequesting InfoAliffia GanisNo ratings yet

- 4.2 Astronomical Instrumentation 2Document27 pages4.2 Astronomical Instrumentation 2Muhammad Nurazin Bin RizalNo ratings yet

- Catálogo de Repuestos: 318 683 4631 Celusilva Cursos 350 530 0174Document9 pagesCatálogo de Repuestos: 318 683 4631 Celusilva Cursos 350 530 0174Javier ReyNo ratings yet