Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Anxiety and Speaking English As A Second Language: RELC Journal December 2006

Uploaded by

jorge CoronadoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Anxiety and Speaking English As A Second Language: RELC Journal December 2006

Uploaded by

jorge CoronadoCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/258182758

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

Article in RELC Journal · December 2006

DOI: 10.1177/0033688206071315

CITATIONS READS

387 26,039

1 author:

Lindy Woodrow

The University of Sydney

36 PUBLICATIONS 1,049 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Lindy Woodrow on 19 November 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

RELC Journal

http://rel.sagepub.com

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

Lindy Woodrow

RELC Journal 2006; 37; 308

DOI: 10.1177/0033688206071315

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://rel.sagepub.com/cgi/content/abstract/37/3/308

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

Additional services and information for RELC Journal can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://rel.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://rel.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

Article

Anxiety and Speaking English

as a Second Language

Lindy Woodrow

University of Sydney, Australia

l.woodrow@edfac.usyd.edu.au

Abstract ■ Second language anxiety has a debilitating effect on the oral performance

of speakers of English as a second language. This article describes a research project

concerning the conceptualization of second language speaking anxiety, the relation-

ship between anxiety and second language performance, and the major reported causes

of second language anxiety. The participants in this study were advanced English for

academic purposes (EAP) students studying on intensive EAP courses immediately

prior to entering Australian universities (N = 275). The second language speaking

anxiety scale (SLSAS) was developed for the study. This instrument provided evi-

dence for a dual conceptualization of anxiety reflecting both oral communication

within and outside the language learning classroom. The scale was validated using

confirmatory factor analysis. The analysis indicated second language speaking anxiety

to be a significant predictor of oral achievement. Reported causes of anxiety were

investigated through interviews. The results indicate that the most frequent source of

anxiety was interacting with native speakers. Evidence for two types of anxious

language learner emerged; retrieval interference and skills deficit. There was an

indication from the study that English language learners from Confucian Heritage

Cultures (CHCs), China, Korea and Japan were more anxious language learners than

other ethnic groups.

Keywords ■ Anxiety, confirmatory factor analysis, English for academic purposes,

second language learning, tertiary education.

Introduction

An increasing number of international students study at universities in

Australia. Students from China represent the largest group and numbers

are increasing. Prior to engaging in further studies international students

need to attain a certain level of English proficiency. Many students do this

Vol 37(3) 308-328 | DOI: 10.1177/0033688206071315

© 2006 SAGE Publications (London, Thousand Oaks CA and New Delhi)

http://RELC.sagepub.com

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

309

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

by attending intensive English language courses prior to university entry.

Research into factors affecting the successful acquisition of English lan-

guage skills and adaptation to the social and academic environment will

benefit these students.

Anxiety experienced in communication in English can be debilitating

and can influence students’ adaptation to the target environment and ulti-

mately the achievement of their educational goals. Most research in this

area focuses on classroom based anxiety. This research considers second

language anxiety as a two-dimensional construct reflecting communication

within the classroom and outside the classroom in everyday communica-

tive situations.

This study sought to investigate the construct of language learning

anxiety of a sample of students studying English for academic purposes.

The study addresses the conceptualization of anxiety communicating in

English, and the relationship between this anxiety and performance in

English. Confirmatory factor analysis was used to determine the construct

structure and correlational analysis was used to investigate the relationship

between anxiety and oral performance in English. The study assumed lan-

guage learning anxiety to be debilitating and investigated the reported

causes using qualitative methods.

Background

In the past two decades there has been a great deal of research into second

or foreign language anxiety. This research indicates that anxiety has a

debilitating effect on the language learning process. There is evidence

that language learning anxiety differs from other forms of anxiety. Early

research into language learning anxiety used measures of test anxiety from

educational research. However, these studies produced inconsistent results

(Scovel 1978; Young 1991). Further, MacIntyre and Gardner’s research

indicates that language learning anxiety is too specific to be captured by

general anxiety measures (MacIntyre and Gardner 1989, 1991a). A dis-

tinction is made in this study between learning English as a foreign lan-

guage and learning English as a second language. It is argued that living in

an environment where the target language is also the language of everyday

communication may influence anxiety.

In educational research, anxiety is usually classified as being trait or

state. Trait anxiety is a relatively stable personality trait. A person who

is trait anxious is likely to feel anxious in a variety of situations. State

anxiety, on the other hand, is a temporary condition experienced at a par-

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

310

Regional Language Centre Journal 37.3

ticular moment. A third type of anxiety is situation specific anxiety. This

reflects a trait that recurs in specific situations (Spielberger, Anton and

Bedell 1976). Research into language learning anxiety has indicated that

language learning be classed as situation specific (MacIntyre and Gardner

1991b; Horwitz 2001). That is, a trait which recurs in language learning

situations, namely classrooms.

Anxiety reactions can be categorized as reflecting worry or emotion-

ality (Leibert and Morris 1967). Emotionality refers to physiological

reactions, such as blushing or racing heart, and behavioural reactions, such

as, stammering and fidgeting. Worry refers to cognitive reactions, such as

self-deprecating thoughts or task irrelevant thoughts (Zeidner 1998;

Naveh-Benjamin 1991). Worry is seen as the more debilitating of the two

because it occupies cognitive capacity that otherwise would be devoted to

the task in hand, for example, speaking a foreign language (Tobias 1985).

Two models of anxiety emerged from Tobias’ research: an interference

model of anxiety and an interference retrieval model. An interference

retrieval model relates to anxiety as inhibiting the recall of previously

learned material at the output stage, whereas a skills deficit model relates

to problems at the input and processing stages of learning, as a result of

poor study habits, or a lack of skills. This results in anxiety at the output

stage due to the realization of this lack of knowledge. Recent research in

language learning has provided some support for this theory (MacIntyre

and Gardner 1994; Onwuegbuzie, Bailey and Daley 2000).

Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope (1986) made a valuable contribution to

theorizing and measurement in language learning anxiety. They consid-

ered anxiety as comprising three components: communication apprehen-

sion, test anxiety and fear of negative evaluation. Horwitz and colleagues

viewed the construct of foreign language anxiety as more than a sum of its

parts and define foreign language anxiety as ‘a distinct complex of self-

perceptions, beliefs, feelings and behaviors related to classroom learning

arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process’ (Horwitz,

Horwitz and Cope 1986; Horwitz 1986). Emerging from this research was

the thirty-three item Foreign Language Anxiety Scale (FLCAS). This scale

has been used in a large number of research projects (Horwitz 2001). The

scale has been found to be reliable and valid (Aida 1994; Cheng, Horwitz

and Schallert 1999).

Most language learning anxiety research has focused on a one dimen-

sional domain anxiety. This conceptualization reflects the anxiety that

occurs in classroom settings (Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope 1986; Aida 1994;

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

311

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

Phillips 1992). The orientation of this conceptualization rests with the

linguistic setting of the students learning the language. A lot of research

into language learning anxiety is based in the United States where foreign

language courses are a requirement of undergraduate degree programs.

This is a foreign language situation where most of the communication in

the target language takes place in the classroom. Other research focuses on

learning English in a non-English speaking country. In a second language

situation, such as Australia, where the target language is also the main lan-

guage of communication outside of the classroom, it was felt that the

conceptualization should be expanded to reflect potential situations beyond

the classroom that could trigger language anxiety. It is possible that class-

room communication could be considered less anxiety provoking than

many communicative events faced in everyday life by students living in a

second language environment.

Instrumentation to measure foreign language anxiety typically uses

Likert type scales to measure responses to stressors. Horwitz’s FLCAS

includes items relating to communication apprehension, for example, ‘I

tremble when I know that I’m going to be called on in the language class’;

test anxiety, for example, ‘I am usually at ease during tests in my lan-

guage class’; and fear of negative evaluation, for example, ‘I get nervous

when the language teacher asks questions which I haven’t prepared in

advance’. In the original published study empirical evidence for classi-

fication was not presented. However, in a factor analytical study of FCLAS

used with students learning Japanese, Aida (1994) produced a four-factor

model: factor one reflected speech anxiety, fear of failing, comfortableness

in speaking with native Japanese, and negative attitudes toward the Japa-

nese class. MacIntyre and Gardner’s (1994) instrument focused on the

stages of foreign language anxiety, that is: input, processing and output

stages. An example of an item in the input anxiety scale is ‘I get flustered

unless French/Spanish/German/Japanese is spoken very slowly’; an exam-

ple from the processing stage is: ‘I feel anxious if the French/Spanish/

German/Japanese class seems disorganized’; an example of the output

stage is ‘I may know the proper French/Spanish/German/ Japanese

expression but when I am nervous it just won’t come out’. It is interesting

to note that most of the items used to measure language anxiety include

anxiety reactions, for example, ‘I tremble’ or ‘I get flustered’. Thus, add-

ing the dimension of worry and emotionality to the scales although this is

not exploited or discussed in any detail in any of the foreign language

anxiety studies.

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

312

Regional Language Centre Journal 37.3

The major significance of research into foreign/second language anxi-

ety is in the relationship between anxiety and performance in the foreign

language. Numerous studies have found that this anxiety is negatively

related to language performance with some researchers claiming it is one

of the strongest predictors of foreign language success (MacIntyre 1999).

Table 1 summarizes the findings of some of the correlational studies

involving foreign/second language anxiety.

Table 1. Relationship between Foreign Language Anxiety and Performance Variables

Researcher Measure

Performance Correlation

Horwitz (1986) FLCAS Final course grade r = -.54, p = <.001

Aida (1994) FLCAS Course grade r = -.38, p = <.01

Phillips (1992) FLCAS Oral test grade r = -.40, p = <.01

Cheng (1999) FLCAS Speaking course r = -.28, p = <.001

grade

Saito and Samimy Language class Final course grade r =.-51 - -.52, p = <.01

(1996) anxiety

MacIntyre and French class Vocabulary test r = .-31 - -.42, p = <.001

Gardner (1989) anxiety

French use r = .-32 - -.50

anxiety

Much focus has been on the relationship between the skill of speaking in a

foreign/second language and anxiety (Lucas 1984; Phillips 1992; Price

1991). Although recent research explores other language skills, for exam-

ple, writing (Cheng, Horwitz and Schallert 1999); reading (Saito, Horwitz

and Garza 1999); and listening (Kim 2000). For a review of foreign lan-

guage anxiety and achievement see Horwitz (2001).

The Study

The present study aims to shed light on second language speaking anxi-

ety as experienced by English learners studying in Australia. The study

proposes a dual conceptualization of second language speaking anxiety

reflecting the distinction between classroom communication and com-

munication outside of class. Data were collected using a questionnaire

developed for this purpose. The relationship between second language

anxiety and speaking performance was examined and the major causes of

anxiety are considered. The study set out to answer the following research

questions:

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

313

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

1. Is a dual conceptualization of second language anxiety according

to in-class and out-of-class communication supported?

2. Is the instrumentation to measure second language anxiety reli-

able and valid?

3. Is there a relationship between speaking performance and second

language speaking anxiety?

4. What are the major stressors reported by students learning English

in Australia?

Participants

The participants for this study were all in their final months of studying

English immediately prior to enrolling on university courses in Australia

(N = 275, 50.5% male, n = 139; 49.5% female, n = 136). They attended

English for Academic Purposes (EAP) courses at accredited intensive

language centres in Australia. The majority of students were from Asian

countries (83.2%, n = 229) with students from China representing the larg-

est group in the sample (34%, n = 92).

At the time of the data collection most of the students still needed to

take a language test to determine adequate English proficiency for univer-

sity entry. The most widely used test for university entry in Australia is the

International English Language Testing Service (IELTS) test.

Methodology

The study involved three sources of data; quantitative data from the Sec-

ond Language Anxiety Speaking Scale, IELTS type oral assessment and

qualitative data from the interview data.

The existing instrumentation used to measure language learning anxi-

ety was not considered appropriate because it did not reflect the second

language environment of the sample, so the second language speak-

ing anxiety scale (SLSAS) was constructed. The instrument was piloted

and refined based on empirical and theoretical justifications (Woodrow

2003).

The questionnaire consists of twelve items on a five-point Likert type

scale. The items reflected the communicative situations the participants

were likely to encounter according to the communicative setting, inter-

locutor (speaker/listener) variables and the nature of the communication.

The communicative setting items concerned the in-class/out-of-class dis-

tinction. The interlocutor variables referred to the number of speakers, the

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

314

Regional Language Centre Journal 37.3

status of the speakers and whether the speaker was a native or non-native

speaker of English. The items for out-of-class communication took into

consideration the communication between the participant and his/her future

academic lecturer. Most of the sample were enrolling on graduate courses

at university and needed to talk to Faculty about this. These items are dif-

ferent from the linguistic communication within the English language

classroom itself. The nature of communication reflected initiating and

responding in oral interaction. The items were measured by the extent to

which the participants agreed or disagreed with the statements.

The performance variable was measured using an IELTS type oral

assessment. This assessment took approximately ten minutes and con-

sisted of three stages: introduction and general interview, individual

long turn and two way discussion. The first stage generally probed the

student’s ability, the second stage involved the student giving a short

monologue and the third stage pushed the student to his/her linguistic

ceiling. The participants were assessed according to descriptors based

on fluency, language usage and pronunciation. The students were given

grades ranging from A–F with an F signifying the student was unlikely

to be accepted onto a university course based on English language

proficiency.

Forty-seven participants took part in an interview with the researcher.

The interview participants were selected based on class groupings, ethnic-

ity, gender and perception of anxiety so that a representative sample of

participants could be surveyed. The participants took part in a semi-

structured interview concerning their experiences of second language

speaking anxiety. The interviews were used to triangulate the data and to

provide further insights into perceived stressors in speaking English in a

second language environment. The participants were asked about whether

they experienced second language speaking anxiety, in what situations

they felt anxious, and how they felt. These interviews were audio recorded

and transcribed.

Results

The results indicated support for a dual conceptualization of second lan-

guage anxiety and the questionnaire was found to be reliable and valid. A

significant negative relationship was found between second language

speaking anxiety and oral performance. The major stressor identified by

the participants was interacting with native speakers.

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

315

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

To assess whether an in-class and out-of-class distinction of second

language anxiety was appropriate and to assess the validity and reliability

of the questionnaire, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) using LISREL

was computed. CFA was chosen to confirm hypothesized latent variables

made a-priori. The assumptions of CFA concern sample size and multi-

variate normality. CFA is a technique classed as structural equation mod-

eling (SEM). SEM is less reliable with small samples and Chi Square (χ2)

tests of data fit are sensitive to sample size. According to Boomsa (1983,

cited in Tabachnick and Fidell 1996: 715) a sample size of two hundred is

adequate for small and medium sized models. Therefore, the sample size

in this study was adequate.

Multivariate outliers were removed from the data using the malanho-

bis statistic using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) com-

puter software. Critical values of χ2 were assessed at p = <.001. No cases

exceeded this level in the sub-scales.

The CFA model used a correlation rather than covariance matrix be-

cause the items were from a five-point Likert scale, and therefore, the

variables could not be classed as truly continuous.

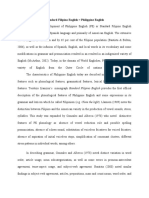

A two factor model best fitted the data with the observed variables

loading on latent variables of in-class anxiety and out-of-class anxiety.

Although the two latent variables were highly correlated a two factor

model provided a better fit to the data than a one factor model. The model

is presented in Figure 1. Item seven of the SLSAS referring to commu-

nication with administrative staff in the language centre seemed ambigu-

ous. It could be classified as both in-class and out-of-class anxiety, so the

item was removed from the analysis. There was an indication of a correla-

tion between variables relating to native speaker interaction, so an error

covariance was included between these. A further error covariance was

included which seemed to reflect public performance: answering a ques-

tion from the teacher and giving an oral presentation. To evaluate the

model, multiple fit indices were used. The model fit indices are shown in

Table 2. The model provided a moderate fit to the data with the goodness

of fit index (GFI) at .90, the comparative fit index at .93 and the non-

normed fit index at .90 (Holmes and Smith 2000). This indicates that the

conceptualization of second language speaking anxiety according to in-

and out-of-class communication is relevant to language learners in an ESL

environment.

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

316

Regional Language Centre Journal 37.3

Figure 1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Second Language Speaking Anxiety

χ2 p χ2/df RMR RMSEA GFI AGFI CFI NFI NNFI

172.62 .00 4.32 .07 .11 .90 .83 .93 .84 .90

Table 2. Fit Indices for Two Factor Confirmatory Factor

Analysis of Second Language Speaking Anxiety

Chi-square (χ2)

Probability (p)

Degrees of freedom (df)

Root mean square residual (RMR)

Root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA)

Goodness of fit index (GFI)

Adjusted goodness of fit index (AGFI)

Comparative Fit Index (CFI)

Normed fit index (NFI)

Non-normed fit index (NNFI)

Reliability for the SLAS was calculated based on the CFA model. This

method is considered superior to the traditional alpha (α) coefficient since

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

317

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

error variance is accounted for. Reliability for in-class anxiety was .89 and

for out-of-class .87 and for the combined scales .94. These indices indicate

that the SLSAS is a reliable instrument.

To assess the relationship between second language speaking anxiety

and oral performance, correlations were computed using the Pearson

correlation coefficient in SPSS. The results indicated that there were

significant negative correlations between both in-class and out-of-class

anxiety and oral performance (in-class anxiety and oral performance:

r = -.23, p = <.01; out-of-class anxiety and oral performance: r = -.24,

p = <.01). The correlation between in-class and out-of-class anxiety was:

r = .58, p = <.01. These results are presented in Table 4. The correlations

indicate that both types of anxiety are related to performance almost

equally. However, the correlation between in-class and out-of-class anxi-

ety is not high enough to suggest they are the same, thus, supporting the

findings of the CFA. The descriptive statistics for the questionnaire data

are presented in Table 3 and the results for individual anxiety variables

and oral performance are presented in Table 5. These results indicate that

participants found communicating with the teacher and performing in

front of the class to be most stressful.

Table 3. Means and Standard Deviations for

Second Language Speaking Anxiety Scale

Variable M SD

In-class anxiety

Giving oral presentation 2.93 1.09

Role-play in front of class 2.73 1.02

Contribute formal discussion 2.61 1.99

Answer question teacher 2.05 1.93

Speak informally teacher 1.81 1.82

Take part group discussion 1.74 1.87

Out-of-class anxiety

Answer question lecturer 2.65 1.02

Ask question lecturer 2.35 1.02

Take part in conversation with 2.35 1.03

more than one NS

Answer questions NS 2.23 1.01

Start conversation NS 1.93 1.96

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

318

Regional Language Centre Journal 37.3

Table 4. Correlations between Anxiety Sub-scales and Oral Performance

Anxiety in-class Anxiety out-of-class Oral performance

Anxiety in-class 1.00

Anxiety out-of-class 1.58 1.00

Oral performance -.23 -.24 100

Correlations significant at p = <.01

Table 5. Correlations between Second Language

Speaking Variables and Oral Performance

Anxiety variable Oral performance

Answer teacher r = -.23, p = <01

Informal teacher r = -.24, p = <01

Group discussion r = -.15, p = <05

Role-play r = -.26, p = <01

Oral presentation r = -.06, ns

Formal discussion r = -.12, p = <05

More than 1 NS r = -.17, p = <01

Start conversation NS r = -.18, p = <01

Answer subject lecturer r = -.21, p = <01

Ask subject lecturer r = -.19, p = <01

Answer NS r = -.21, p = <01

A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was conducted to exam-

ine the influence of ethnicity and sex on anxiety. This indicated a sig-

nificant effect for ethnic group: V = 015, F(18,492) = 2.28 p<0.01. There

was no significant effect for sex: V = .005, F(2,245) = .64 p =.53.

Further univariate analyses of variance (ANOVAS) indicated sig-

nificant main effects of ethnic group on in class anxiety: F(9, 246) = 2.69,

p<.01, η2 = .09 and on out-of- class anxiety: F(9, 246) = 3.45, p<.00001,

η2 = .11.

Using a significance level of .05 Tukey’s HSD post hoc tests indicated

significant differences between European and Korean participants on in

class anxiety and Vietnamese and Korean, Vietnamese and Japanese and

Vietnamese and Taiwanese on out-of-class anxiety. This indicates some

evidence for a distinction between CHCs and other cultures.

To assess the major stressors, interview data were used. The interviews

were audio recorded and transcribed. The interview data were coded

according to categories relating to stressors, reactions and coping strate-

gies. The data revealed that of the forty-seven coded interviews, forty

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

319

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

(85%) of the participants claimed to experience second language speaking

anxiety to some extent.

The major stressors reported by the respondents were ‘performing in

front of class’ and ‘talking to native speakers’. Table 6 shows the fre-

quencies of the stressors reported by the interviewees.

Table 6. Reported Stressors Based on Interview Data when Speaking in English

Stressor N %

Performing in English in front of classmates 21 44.7

Giving an oral presentation 20 42.7

Speaking in English to native speakers 18 42.7

Speaking in English in classroom activities 19 19.1

Speaking in English to strangers 19 19.1

Not being able to understand when spoken to 18 17.0

Talking about an unfamiliar topic 18 17.0

Talking to someone of higher status 18 17.0

Speaking in test situations 17 14.9

When interlocutor seems stern 16 12.7

Not being able to make self understood 15 10.6

Information regarding anxiety reactions revealed that more respondents

reported physiological (n = 24, 51.1%) and cognitive reactions (n = 23,

48.9%) than behavioural (n = 16, 34%) reactions. Physiological reactions

included sweating, racing heart and blushing and cognitive reactions

included worrying about performance and mind going blank. Behavioural

reactions included fidgeting, talking too much and stuttering.

Emerging from the data, approximately half of the respondents referred

to methods they used to cope with second language speaking anxiety.

Perseverance and developing skills were the most frequently mentioned

coping strategies. Table 7 summarizes some of these responses.

Table 7. Reported Methods of Coping with Second

Language Speaking Anxiety (N = 24)

Coping strategy n %

Perseverance 8 33.3

Improving language /knowledge skills 7 29.2

Positive thinking 4 16.7

Compensation 4 16.7

Relaxation techniques 3 12.5

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

320

Regional Language Centre Journal 37.3

‘Perseverance’ refers to not giving up when speaking while ‘improving

language’ refers to preparing utterances and studying to improve speak-

ing. ‘Positive thinking’ included positive self-talk while ‘compensation

strategies’ included smiling and volunteering comments. Various relaxa-

tion techniques were mentioned, such as deep breathing and conscious

efforts to calm oneself.

Discussion

The first research question refers to the relevance of a dual conceptualiza-

tion of second language speaking anxiety. The results indicate that this is

a useful distinction to make with learners in a second language learning

environment where a great deal of communication in the second language

occurs outside of the classroom. The indicated that while in-class and out-

of-class anxiety are highly correlated (r = .58, p = <.01), they are not the

same construct. The qualitative data also provided support for an in-class

and out-of-class distinction. Some participants reported experiencing out-

of-class anxiety. Michael reported:

I always feel a little anxious when I speak with native speakers and not

inside class but outside class. Because when I speak in class I pay

money for it. I am afraid of nothing. But when I speak in the street

sometimes…especially when maybe young Australians.

This is an interesting viewpoint, the language class here is viewed as a

product.

Harry also reported feeling anxious when speaking in English out-of-

class:

I feel anxiety when I talk with native English speakers because I know

my English…my speaking English…is not correct, so maybe it makes

the native English speakers confused and maybe sometimes what I’m

speaking…what I’m talking about is not interesting to native speakers. I

think so these kinds of things.

Harry is concerned with whether the listener can understand.

In contrast some participants referred to in-class anxiety. Phillip states;

When I stand in front of classmates and students and make a presenta-

tion I will feel anxious because I lack practice of speaking.

Whereas Lesley states:

When I speak to my teacher and ask some question to my teacher I

usually feel very anxious. And when I say to the in front of the English

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

321

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

class and speak some question some topic I usually very anxious. I can’t

remember anything I just maybe ah… ah… ah.

Whilst the types of anxious learners were not the direct focus of the

research evidence to support a distinction between these types of anxiety

emerged from the interview data. From the above responses it seems that

Philip feels his anxiety is due to lack of practice thus relating to a skills

deficit type of anxiety. Lesley, on the other hand seems to be experiencing

information retrieval anxiety, that is, anxiety is preventing the recall of

previously learned material when she cannot remember anything.

The second research question considers the reliability and validity of

the instrumentation. A new instrument was developed to measure anxiety

in a second language environment—the second language speaking anxiety

scale (SLSAS).The instrumentation achieved validity through providing a

reasonable fit to the CFA model. Reliability was established using a

coefficient based on the model that took error into account.

The third research question concerns the relationship between second

language speaking anxiety and oral performance in the second language

using an IELTS type oral assessment. The correlational analysis indi-

cated a negative relationship between both in-class anxiety and out-of-

class anxiety and oral performance. Providing evidence that anxiety can

adversely affect oral communication for students speaking English. These

results replicate the findings of other researchers in the area (see Table 1).

The negative correlation between oral performance and anxiety is not very

strong. This is understandable because anxiety is just one of a number of

variables influencing successful communication. However, this research

indicates that anxiety does influence oral communication. In a larger re-

search project into variables of adaptive learning comprising affect,

motivation and learning strategies anxiety was found to be an important

part of the model (Woodrow 2003).

The fourth research question concerns the stressors reported by the sam-

ple. According to the quantitative data, giving oral presentations was rated

the highest and taking part in group discussions was rated the lowest.

Whilst the cohort as a whole did not demonstrate very high speaking

anxiety there was evidence of variation between nationality groups with

European and Vietmanese participants tending to be less anxious and

Japanese, Korean and Chinese participants tending to be more anxious.

Most previous research into anxiety is situated in a western setting, how-

ever, there are many examples of differences between Confucian heritage

learners and western learners in academic contexts (Watkins and Biggs

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

322

Regional Language Centre Journal 37.3

1996, 2001). Research has indicated a relationship between reticence in

classrooms of Chinese learners and Confucian values of ‘face’ and value

being place on ‘silence’ (Liu 2002). Current research has indicated culture

may also be manifested in students’ willingness to communicate (WTC)

(Wen and Clement 2003; Yashima 2002). Anxiety is hypothesized as one

of the antecendents of WTC (MacIntyre, Baker, Clément and Conrod

2001). There is a need for further research in this area.

The qualitative data indicated that giving oral presentations and per-

forming in front of classmates were the most reported stressors for in-class

situations. However, the correlational data indicated that ‘giving an oral

presentation’ was the only anxiety variable that was not significantly cor-

related with oral performance. This would be an interesting avenue for

further research. One possible explanation for this discrepancy is that the

oral assessment task in the research involved the participants producing a

‘long turn’ whereby the student was required to speak for one to two

minutes on a topic rather than a formal presentation. In addition, the oral

assessment involved one to one communication rather than one to an audi-

ence. Such long turns frequently occur in normal communication, whereas

giving an oral presentation rarely occurs in everyday communication.

Thus, giving an oral presentation calls upon different communicative skills

than were measured in the oral assessment. The most highly correlated

variables reflected interaction. The correlations between the observed vari-

ables and oral performance are presented in Table 6.

Interestingly, nearly all of the interview participants reported experi-

encing some anxiety when speaking in English. ‘Communicating with

native speakers’ was the most referred to out-of-class stressor. However,

the level of predictability is also a consideration. Miko reported that she

felt most anxious with native speakers, but not in situations where there is

a high degree of linguistic predictability. In answer to a question about the

situations in which she felt most anxious she answered:

…of course to speak to native speaker and which is not my teacher or

some people I know, which is stranger. But I am not afraid to speak to

the storekeeper or something. I can speak to them. Just people on the

street or on the train, I am afraid of speaking to them because I worry

about my grammar mistakes basically.

Some participants referred to the number of native speakers involved in

the interaction:

Lu responded to the same question about the situations in which she

felt most anxious:

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

323

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

Talk with more than one native speaker. Because when I talk with one

person we can communicate effectively and there is only one listener,

one audience. But more than one person maybe I will think someone

maybe do not agree with me and maybe we will argue. Just a feel-

ing…just a feeling.

The study indicated that the participants attributed anxiety to a range of

factors, but particularly referred to communication with native speakers.

Interaction with non-native speakers was not considered a stressor by most

of the sample. In a similar vein, the study also indicated low anxiety for

group discussions. This lends support to using collaborative techniques

that focus on student–student interaction.

Some participants talked about some of the ways they dealt with their

speaking anxiety. Some students referred to perseverance. For example

Hero said:

I think to try speaking again and again is the best way to solve it

(anxiety). Keep or let my mind to calm down, be natural and like

speaking to Japanese people.

In addition to perseverance this student tries to use relaxation tech-

niques to deal with his anxiety. This is a recommended strategy for deal-

ing with anxiety. Skills deficit anxious individuals benefit from improving

learning strategies and focusing on learning the necessary skills and lin-

guistic features of the language whereas interference retrieval anxious

individuals can focus on relaxation techniques and positive self-talk

(Young 1991; Zeidner 1998).

Conclusions

This study found that a dual conceptualization of second language speak-

ing anxiety as measured by the second language speaking anxiety scale

was relevant to students studying English in Australia. The results indicate

that the instrument is reliable and valid and thus provides researchers with

a new instrument to measure second language speaking. It would be inter-

esting to use this with second language speakers of a lower linguistic level

and also with students after they have started their university courses to

investigate contextual influences on second language speaking anxiety.

Anxiety is clearly an issue in language learning and has a debilitating

effect on speaking English for some students. So it is important that teach-

ers are sensitive to this in classroom interactions and provide help to

minimize second language anxiety.

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

324

Regional Language Centre Journal 37.3

The study also provided support for the notion of stages of anxiety.

Thus, a student may experience anxiety due to skills deficit or retrieval

interference. This has implications at a classroom level. A skills deficit

anxious student would benefit from instruction in language learning strate-

gies and scaffolding of skills whereas a retrieval interference anxious

student would benefit from de-sensitization and relaxation techniques. It is

important to take into consideration communication both in and outside

the classroom and ensure that students have the necessary skills and prac-

tice for everyday communication. This could be achieved by setting out-

of-class tasks utilizing the rich linguistic resources available to learners.

For example, students could join a local library and participate in local

community activities as well as participating in the university community.

Finally, there is a need for empirical evidence concerning how effective

anxiety reducing techniques are in second language learning classrooms.

REFERENCES

Aida, Y.

1994 ‘Examination of Horwitz and Cope’s Construct of Foreign Language Anxiety:

The Case of Students of Japanese’, Modern Language Journal 78(2): 155-67.

Chastain, K.

1975 ‘Affective and Ability Factors in Second Language Acquisition’, Language

Learning 25: 153-61.

Cheng, Y.S., E.K. Horwitz and D.L. Schallert

1999 ‘Language Anxiety: Differentiating Writing and Speaking Components’,

Language Learning 49: 417-46.

Gardner, R.C., and P.D. MacIntyre

1993 ‘A Student’s Contribution to Second Language Learning, Part II: Affective

Variables’, Language Teaching 26: 1-11.

Gardner, R.C., P. Smythe, R. Clement and L. Gliksman

1976 ‘Second Language Learning: A Social Psychological Perspective’, Canadian

Modern Language Review 32: 198-213.

Holmes-Smith, P.

2000 Introduction to Structural Equation Modeling Using LISREL (School Re-

search, Evaluation and Measurement Services).

Horwitz, E.K.

1986 'Preliminary Evidence for the Reliability and Validity of a Foreign Language

Anxiety Scale', in E.K. Horwitz and D.J. Young (eds.), Language Anxiety:

From Theory to Research to Classroom Practices (New York: Prentice Hall).

2001 ‘Language Anxiety and Achievement’, Annual Review of Applied Linguistics

21: 112-26.

Horwitz, E.K., M.E. Horwitz and J. Cope

1986 ‘Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety’, Modern Language Journal 70: 125-

32.

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

325

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

Jöreskog, K.G., and D. Sorbom

1996 LISREL 8: User’s Reference Guide (Chicago: Scientific Software Interna-

tional).

Kim, J.H.

2000 'Foreign Language Listening Anxiety: A Study of Korean Students Learning

English' (Unpublished thesis, University of Texas, Austin).

Kleinmann, H.H.

1977 ‘Avoidance Behavior in Adult Second Language Acquisition’, Language

Learning 27(1): 93-107.

Liebert, R.M., and L.W. Morris

1967 ‘Cognitive and Emotional Components of Anxiety: A Distinction and Some

Initial Data’, Psychological Reports 20: 975-78.

Liu, J.

2002 ‘Negotiating Silence in American Classrooms: Three Chinese Cases’, Lan-

guage and Intercultural Communication 2(1): 37-54.

Lucas, J.

1994 ‘Communication Apprehension in the ESL Classroom: Getting our Students

to Talk’, Foreign Language Annals 17: 593-98.

MacIntyre, P.D.

1999 ‘Language Anxiety: A Review of the Research for Language Teachers’, In

D.J. Young (ed.), Affect in Foreign Language and Second Language Learn-

ing: A Practical Guide to Creating a Low-anxiety Classroom Atmosphere

(Boston: McGraw-Hill College): 24-45.

MacIntyre, P.D., and R.C. Gardner

1989 ‘Anxiety and Language Learning: Towards a Theoretical Clarification’, Lan-

guage Learning 39: 251-75.

1991a ‘Language Anxiety: Its Relationship to Other Anxieties and to Processing in

Native and Second Languages’, Language Learning 41: 85-117.

1991b ‘Methods and Results in the Study of Anxiety and Language Learning: A

Review of the Literature’, Language Learning 41: 513-34.

1994 ‘The Subtle Effects of Anxiety on Cognitive Processing in the Second Lan-

guage’, Language Learning 44(2): 283-305.

MacIntyre, P.D., S.C. Baker, R. Clément and S. Conrod

2001 'Willingness to Communicate, Social, Support and Language Learning Orien-

tations of Immersion Students’, Studies in Second Language Acquisition 23:

369-88.

Naveh-Benjamin, M.

1991 ‘A Comparison of Training Programs Intended for Different Types of Test

Anxious Students: Further Support for an Information-processing Model’,

Journal of Educational Psychology 83(1): 134-39.

Onwuegbuzie, A.J., P. Bailey and C.E. Daley

2000 ‘The Validation of Three Scales Measuring Anxiety at Different Stages of the

Foreign Language Learning Process: Input Anxiety Scale, Processing Anxiety

Scale, Output Anxiety Scale’, Language Learning 50(1): 87-117.

Phillips, E.

1992 ‘The Effects of Language Anxiety on Student Test Oral Performance’, The

Modern Language Journal 76: 14-26.

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

326

Regional Language Centre Journal 37.3

Price, M.L.

1991 ‘The Subjective Experience of Foreign Language Anxiety: Interviews with

Highly Anxious Students’, in E.K. Horwitz and D.J. Young (eds.), Foreign

Language Anxiety: From Theory to Research to Classroom Practices (Engle-

wood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall).

Saito, Y., E.K. Horwitz and T.J. Garza

1999 ‘Foreign Language Reading Anxiety’, Modern Language Journal 83: 202-18.

Scovel, T.

1978 ‘The Effect of Affect on Foreign Language Learning: A Review of the

Anxiety Research’, Language Learning 28(1): 129-41.

Spielberger, C., W. Anton and J. Bedell

1976 ‘The Nature and Treatment of Test Anxiety’, in M. Zuckerman and C. Spiel-

berger, Emotions and Anxiety: New Concepts, Methods and Applications

(Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum): 317-44

Tabachnick, B.G., and L.S. Fidell

1996 Using Multivariate Statistics (California State University: Harper Collins

College Publishers).

Tobias, S.

1985 ‘Test Anxiety: Interference, Defective Skills and Cognitive Capacity’, Educa-

tional Psychologist 3: 135-42.

Watkins, D.A. and J.B. Biggs

1996 The Chinese Learner: Cultural, Psychological and Contextual Influences

(Hong Kong and Melbourne: CERC and ACER).

2001 Teaching the Chinese Learner: Psychological and Pedagogical Influences

(Hong Kong and Melbourne: CERC and ACER).

Wen, W.P., and R. Clément

2003 ‘A Chinese Conceptualisation of Willingness to Communicate in ESL’,

Language, Culture and Curriculum 16: 18-38.

Woodrow, L.J.

2001 Towards a Model of Adaptive Language Learning: A Pilot Study (ERIC

Documents, ED456645).

2003 ‘A Model of Adaptive Learning of International English for Academic

Purposes (EAP) at Australian Universities’ (Unpublished doctoral thesis,

University of Sydney).

Yashima, T.

2002 ‘Willingness to Communicate in a Second Language: The Japanese EFL

Context’, The Modern Language Journal 86: 54-66.

Young, D.J.

1991 ‘Creating a Low Anxiety Classroom Environment: What Does Anxiety

Research Suggest?’, Modern Language Journal 75: 426-38.

Zeidner, M.

1998 Test Anxiety: The State of the Art (New York: Plenum Press).

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

327

Anxiety and Speaking English as a Second Language

APPENDIX

Instrument Used in Main Study

In the column Anxiety fill in the circles according to how anxious you feel when you

speak English in the following situations.

1 2 3 4 5

Not at all Slightly Moderately Very Extremely

anxious anxious anxious anxious anxious

Situation Anxiety

1. The teacher asks me a question in English in class. |||||

1 2 3 4 5

2. Speaking informally to my English teacher out of class. |||||

1 2 3 4 5

3. Taking part in a group discussion in class. |||||

1 2 3 4 5

4. Taking part in a role-play or dialogue in front of my class. |||||

1 2 3 4 5

5. Giving an oral presentation to the rest of the class. |||||

1 2 3 4 5

6. When asked to contribute to a formal discussion in class. |||||

1 2 3 4 5

7. Talking to administrative staff of my language school in |||||

English. 1 2 3 4 5

8. Taking part in a conversation out of class with more than |||||

one native speaker of English. 1 2 3 4 5

9. Starting a conversation out of class with a friend or |||||

colleague who is a native speaker of English. 1 2 3 4 5

10. A lecturer/supervisor in my intended university faculty of |||||

study asks me a question in English. 1 2 3 4 5

11. Asking for advice in English from a lecturer/supervisor in |||||

my intended university faculty of study. 1 2 3 4 5

12 A native speaker I do not know asks me questions. |||||

1 2 3 4 5

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

328

Regional Language Centre Journal 37.3

Correlation Matrix for Confirmatory Factor Analysis of Anxiety

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

1 1.00

2 1.66 1.00

3 1.67 1.53 1.00

4 1.56 1.47 1.53 1.00

5 1.50 1.43 1.48 1.70 1.00

6 1.61 1.49 1.56 1.59 1.58 1.00

7 1.37 1.54 1.36 1.30 1.32 1.39 1.00

8 1.35 1.52 1.42 1.29 1.28 1.37 11.85 1.00

9 1.55 1.49 1.40 1.44 1.42 1.44 11.54 1.52 1.00

10 1.45 1.51 1.38 1.38 1.33 11.39 .54 1.52 1.81 1.00

11 1.37 1.43 1.32 1.35 1.28 11.33 1.60 1.60 1.57 1.58 1.00

Key to variables

1 in-class anxiety Answer question teacher

2 in-class anxiety Speak informally to my teacher

3 in-class anxiety Take part in group discussions

4 in-class anxiety Take part in a role-play

5 in-class anxiety Give an oral presentation

6 in-class anxiety Contribute to formal discussions

7 out-of-class anxiety Take part conversation more than one native speaker

8 out-of-class anxiety Start conversation with native speaker

9 out-of –class anxiety Answer question from lecturer

10 out-of-class anxiety Ask lecturer for advice

11 out-of class anxiety Answer question unknown native speaker

Downloaded from http://rel.sagepub.com at PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIV on April 16, 2008

© 2006 SAGE Publications. All rights reserved. Not for commercial use or unauthorized distribution.

View publication stats

You might also like

- Reducing Language Anxiety & Promoting Learner Motivation: A Practical Guide for Teachers of English As a Foreign LanguageFrom EverandReducing Language Anxiety & Promoting Learner Motivation: A Practical Guide for Teachers of English As a Foreign LanguageNo ratings yet

- Research Methodology - Case Study AnalysisDocument8 pagesResearch Methodology - Case Study AnalysisHuyen Le100% (1)

- An Informed and Reflective Approach to Language Teaching and Material DesignFrom EverandAn Informed and Reflective Approach to Language Teaching and Material DesignNo ratings yet

- Linguistic modality in Shakespeare Troilus and Cressida: A casa studyFrom EverandLinguistic modality in Shakespeare Troilus and Cressida: A casa studyNo ratings yet

- ESL Writing Study: Cohesion and CoherenceDocument17 pagesESL Writing Study: Cohesion and CoherenceVan AnhNo ratings yet

- Basic Concepts of LinguisticsDocument7 pagesBasic Concepts of LinguisticsAntonino PaganiniNo ratings yet

- Ferrer - Mother Tongue in The Classroom PDFDocument7 pagesFerrer - Mother Tongue in The Classroom PDFtomNo ratings yet

- Tree of EltDocument25 pagesTree of EltYadirf LiramyviNo ratings yet

- Group 1 - Learners Errors and Error AnalysisDocument32 pagesGroup 1 - Learners Errors and Error Analysisedho21No ratings yet

- How Attitudes, Motivation and Language Aptitude Impact Second Language LearningDocument21 pagesHow Attitudes, Motivation and Language Aptitude Impact Second Language LearningFatemeh NajiyanNo ratings yet

- Roger HawkeyDocument33 pagesRoger HawkeyAna TheMonsterNo ratings yet

- Second Language Research 1997 Bialystok 116 37Document22 pagesSecond Language Research 1997 Bialystok 116 37Mustaffa TahaNo ratings yet

- Vygotskian Principles Genre-Based Approach Teaching WritingDocument15 pagesVygotskian Principles Genre-Based Approach Teaching WritingmardianaNo ratings yet

- i01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationDocument9 pagesi01-2CC83d01 - Intercultural Communication in English Language Teacher EducationMuhammad Iwan MunandarNo ratings yet

- Running Head: APA Style Sample 1Document5 pagesRunning Head: APA Style Sample 1api-359895192No ratings yet

- Chapter 9 PsycholinguisticsDocument72 pagesChapter 9 PsycholinguisticsKurniawanNo ratings yet

- Content Based InstructionDocument20 pagesContent Based InstructionAndrey Shauder GuzmanNo ratings yet

- 1 Reading ResponseDocument3 pages1 Reading ResponseStephen N SelfNo ratings yet

- Critical Language AwarenessDocument8 pagesCritical Language AwarenessDavid Andrew Storey0% (1)

- Content Language Integrated Learning GlossaryDocument13 pagesContent Language Integrated Learning GlossaryJoannaTmszNo ratings yet

- Teaching English as a Lingua FrancaDocument9 pagesTeaching English as a Lingua Francaabdfattah0% (1)

- Lantolf 1994 Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning - Introduction To The Special IssueDocument4 pagesLantolf 1994 Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning - Introduction To The Special IssuehoorieNo ratings yet

- Research Methods in Second Language Acquisition: A Practical GuideFrom EverandResearch Methods in Second Language Acquisition: A Practical GuideRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (5)

- Catford JC 1975 Ergativity in Caucasian LanguaguesDocument59 pagesCatford JC 1975 Ergativity in Caucasian LanguaguesnellyUNNo ratings yet

- Language and PowerDocument21 pagesLanguage and PowerLynette ChangNo ratings yet

- Lexical Approach to Second Language TeachingDocument8 pagesLexical Approach to Second Language TeachingAnastasia KolaykoNo ratings yet

- Bilingualism PDFDocument336 pagesBilingualism PDFhandpamNo ratings yet

- From Cultural Awareness To Intercultural Awarenees Culture in ELTDocument9 pagesFrom Cultural Awareness To Intercultural Awarenees Culture in ELTGerson OcaranzaNo ratings yet

- Metawords in Medical DiscourseDocument4 pagesMetawords in Medical DiscourseIvaylo DagnevNo ratings yet

- Conversational DiscourseDocument71 pagesConversational DiscourseesameeeNo ratings yet

- Semantics and Grammar - verbal and nominal categoriesDocument4 pagesSemantics and Grammar - verbal and nominal categoriesDianaUtNo ratings yet

- Writing and Presenting a Dissertation on Linguistics: Apllied Linguistics and Culture Studies for Undergraduates and Graduates in SpainFrom EverandWriting and Presenting a Dissertation on Linguistics: Apllied Linguistics and Culture Studies for Undergraduates and Graduates in SpainNo ratings yet

- 002 Newby PDFDocument18 pages002 Newby PDFBoxz Angel100% (1)

- Code Switching in Conversation Between English Studies StudentsDocument39 pagesCode Switching in Conversation Between English Studies StudentsTarik MessaafNo ratings yet

- A Flexible Framework For Task-Based Lear PDFDocument11 pagesA Flexible Framework For Task-Based Lear PDFSusan Thompson100% (1)

- Extensive Listening in CLT in EFL ContextDocument9 pagesExtensive Listening in CLT in EFL ContextAbir BotesNo ratings yet

- Introducing Translating Studies Brief Chapter 1 To 5Document26 pagesIntroducing Translating Studies Brief Chapter 1 To 5belbachirNo ratings yet

- Lexis and MorphologyDocument41 pagesLexis and MorphologyNoor Zaman100% (1)

- TMP 6101Document31 pagesTMP 6101FrontiersNo ratings yet

- Applied Linguistics LANE 423-DA-Updated PDFDocument6 pagesApplied Linguistics LANE 423-DA-Updated PDFSara EldalyNo ratings yet

- Micro-linguistic Features of Computer-Mediated CommunicationDocument24 pagesMicro-linguistic Features of Computer-Mediated CommunicationGabriel McKeeNo ratings yet

- Comparing the Formal and Functional Approaches to Discourse AnalysisDocument16 pagesComparing the Formal and Functional Approaches to Discourse AnalysisVan AnhNo ratings yet

- Summary Chapter 2 Learner Errors and Error AnalysisDocument3 pagesSummary Chapter 2 Learner Errors and Error AnalysisRifky100% (1)

- Philippine English CharacteristicsDocument3 pagesPhilippine English CharacteristicsChristine Breeza SosingNo ratings yet

- 90 Paper2 With Cover Page v2Document25 pages90 Paper2 With Cover Page v2Chika JessicaNo ratings yet

- McIntosh, K. (Ed.) - (2020) - Applied Linguistics and Language Teaching in The Neo-Nationalist Era. Palgrave Macmillan.Document329 pagesMcIntosh, K. (Ed.) - (2020) - Applied Linguistics and Language Teaching in The Neo-Nationalist Era. Palgrave Macmillan.Luis Penton HerreraNo ratings yet

- Language and Society SeminarDocument28 pagesLanguage and Society Seminarsiham100% (2)

- James Annesley-Fictions of Globalization (Continuum Literary Studies) (2006)Document209 pagesJames Annesley-Fictions of Globalization (Continuum Literary Studies) (2006)Cristina PopovNo ratings yet

- Al Zayid 2012 The Role of Motivation in The L2 Acquisition of English by Saudi Students - A Dynamic Perspective (THESIS)Document112 pagesAl Zayid 2012 The Role of Motivation in The L2 Acquisition of English by Saudi Students - A Dynamic Perspective (THESIS)hoorieNo ratings yet

- Course OutlineDocument2 pagesCourse OutlinerabiaNo ratings yet

- Building Online Language Learning CommunitiesDocument13 pagesBuilding Online Language Learning Communitiessupongo que yoNo ratings yet

- 08 SpeakingDocument23 pages08 Speakingjorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Cooperative LearningDocument16 pagesCooperative Learningjorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Who is truly bilingual? Defining bilingualismDocument8 pagesWho is truly bilingual? Defining bilingualismjorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- International Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol. Xxii No 2 2016Document6 pagesInternational Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol. Xxii No 2 2016jorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Co-Operative Learning: March 2011Document10 pagesIntroduction To Co-Operative Learning: March 2011jorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- International Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol. Xxii No 2 2016Document6 pagesInternational Conference KNOWLEDGE-BASED ORGANIZATION Vol. Xxii No 2 2016jorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Jacobs PDFDocument9 pagesJacobs PDFJunitia Dewi VoaNo ratings yet

- Cohen, E. Restructuring The ClassroomDocument35 pagesCohen, E. Restructuring The Classroomjorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Pathwaysrw 1 Unit6 PDFDocument20 pagesPathwaysrw 1 Unit6 PDFHishi AnoNo ratings yet

- Leng KapDocument33 pagesLeng KapratrydwiNo ratings yet

- Cohen, E. Restructuring The ClassroomDocument35 pagesCohen, E. Restructuring The Classroomjorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- 2 Improving The Students'Speaking Ability Through The Use of Role PlayingDocument8 pages2 Improving The Students'Speaking Ability Through The Use of Role PlayingfslNo ratings yet

- Cooperative and Collaborative Learning: Getting The Best of Both WordsDocument15 pagesCooperative and Collaborative Learning: Getting The Best of Both Wordsjorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Verb To Be WorksheetDocument2 pagesVerb To Be WorksheetEliana CrespoNo ratings yet

- Jacobs PDFDocument9 pagesJacobs PDFJunitia Dewi VoaNo ratings yet

- 6th Central Pay Commission Salary CalculatorDocument15 pages6th Central Pay Commission Salary Calculatorrakhonde100% (436)

- Second Language Acquisition and Learning - KrashenDocument154 pagesSecond Language Acquisition and Learning - KrashenlordybyronNo ratings yet

- 01 Integrating TechnologyDocument22 pages01 Integrating Technologysupongo que yoNo ratings yet

- Cohen, E. Restructuring The ClassroomDocument35 pagesCohen, E. Restructuring The Classroomjorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 14 Prepositions and ConjunctionsTITLE Prepositions and ConjunctionsDocument13 pagesLesson 14 Prepositions and ConjunctionsTITLE Prepositions and Conjunctionsjorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Developing Speaking PDFDocument10 pagesDeveloping Speaking PDFNurul HikmahNo ratings yet

- Developing Speaking Skills Through Speaking - Oriented WorkshopsDocument11 pagesDeveloping Speaking Skills Through Speaking - Oriented WorkshopsAndres FNo ratings yet

- English Anxiety When Speaking EnglishDocument16 pagesEnglish Anxiety When Speaking EnglishHELENANo ratings yet

- Role Plays in Teaching English For SpeciDocument8 pagesRole Plays in Teaching English For Specijorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Role Play As A Method To Overcome AnxietyDocument5 pagesRole Play As A Method To Overcome Anxietyjorge CoronadoNo ratings yet

- Anxiety and Language Achievement - Horwitz PDFDocument17 pagesAnxiety and Language Achievement - Horwitz PDFNguyen HalohaloNo ratings yet

- A Thesis - Intan Alfi - 11202241002Document247 pagesA Thesis - Intan Alfi - 11202241002Happiness DelightNo ratings yet

- STD 9th Englishpt1Document2 pagesSTD 9th Englishpt1Dr. B V UpadhyayNo ratings yet

- Group 6 - Design The Worksheet Based On The Need AnalysisDocument10 pagesGroup 6 - Design The Worksheet Based On The Need AnalysisIsnatin Nur Hidayah TBI 3BNo ratings yet

- Language VarietyDocument2 pagesLanguage VarietyFatima Aslam100% (2)

- IELTS Pub QuizDocument8 pagesIELTS Pub Quizmadmaxjune17557No ratings yet

- Our PoemDocument6 pagesOur Poemapi-213540529No ratings yet

- Infinitivi, Gerund, ParticipiDocument6 pagesInfinitivi, Gerund, ParticipiMartinaNo ratings yet

- Language Portfolio Ibcp GuidelinesDocument10 pagesLanguage Portfolio Ibcp Guidelinesapi-233401612No ratings yet

- Gaurav Kumar TripathiDocument2 pagesGaurav Kumar Tripathiamit kumar VermaNo ratings yet

- Computer Networks Question BankDocument3 pagesComputer Networks Question BankNitin BirariNo ratings yet

- CP R81 ClusterXL AdminGuideDocument299 pagesCP R81 ClusterXL AdminGuidePhan Sư ÝnhNo ratings yet

- Sansat M3u.loliDocument2 pagesSansat M3u.loliAlfredo Vides100% (1)

- BAFEDM FinalJul 102019Document35 pagesBAFEDM FinalJul 102019venus camposanoNo ratings yet

- READING DIAG WORD David TrejoDocument3 pagesREADING DIAG WORD David TrejoDavid TrejoNo ratings yet

- Pali English DictionaryDocument712 pagesPali English DictionaryIoan AndreescuNo ratings yet

- Cre 7Document30 pagesCre 7epalat evansNo ratings yet

- Advanced Writing SkillsDocument74 pagesAdvanced Writing SkillsThaiHoa9100% (1)

- Mastering Physics CH 02 HW College Physics I LCCCDocument33 pagesMastering Physics CH 02 HW College Physics I LCCCSamuel80% (15)

- Victory Elijah Christian College English Grade 6 June Monthly TestDocument7 pagesVictory Elijah Christian College English Grade 6 June Monthly TestEron Roi Centina-gacutanNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Convective Heat Transfer Analysis Chapter 8 PDFDocument84 pagesIntroduction To Convective Heat Transfer Analysis Chapter 8 PDFhenrengNo ratings yet

- Exercises: Solve A Real-World ProblemDocument3 pagesExercises: Solve A Real-World ProblemPham Quang MinhNo ratings yet

- ESL Lesson PlanDocument4 pagesESL Lesson PlanRalph Julius DomingoNo ratings yet

- Job Opportunities After Post Graduate Diploma in Advanced Computing (PG-DAC)Document2 pagesJob Opportunities After Post Graduate Diploma in Advanced Computing (PG-DAC)Roman PeirceNo ratings yet

- A 1Document68 pagesA 1abcd efghNo ratings yet

- Revision Paper English Class 1XDocument2 pagesRevision Paper English Class 1XSaumya PatelNo ratings yet

- Hiren Resume 1Document3 pagesHiren Resume 1Renee BarronNo ratings yet

- RP4xx Driver Setup ManualDocument20 pagesRP4xx Driver Setup ManualTHE LISTNo ratings yet

- Irismodule AutismDocument4 pagesIrismodule Autismapi-585078296No ratings yet

- ORACLE UNDO SPACE ANALYSISDocument13 pagesORACLE UNDO SPACE ANALYSISKoushikKc ChatterjeeNo ratings yet

- Slot Deposit 10k Gbosky 6Document1 pageSlot Deposit 10k Gbosky 6naeng naengNo ratings yet

- Harsha and His Times: Arun KumarDocument4 pagesHarsha and His Times: Arun KumarPrena MondalNo ratings yet