Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Stace 1949

Stace 1949

Uploaded by

Bruno Thiago0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views11 pagesCopyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

17 views11 pagesStace 1949

Stace 1949

Uploaded by

Bruno ThiagoCopyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 11

Philosophy

http://journals.cambridge.org/PHI

Additional services for Philosophy:

Email alerts: Click here

Subscriptions: Click here

Commercial reprints: Click here

Terms of use : Click here

The Parmenidean Dogma

Professor W. T. Stace

Philosophy / Volume 24 / Issue 90 / July 1949, pp 195 - 204

DOI: 10.1017/S0031819100007178, Published online: 25 February 2009

Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/

abstract_S0031819100007178

How to cite this article:

Professor W. T. Stace (1949). The Parmenidean Dogma. Philosophy, 24, pp

195-204 doi:10.1017/S0031819100007178

Request Permissions : Click here

Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/PHI, IP address: 66.77.17.54 on 25 Jan 2014

PHILOSOPHY

THE JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL INSTITUTE

OF PHILOSOPHY

VOL. XXIV. No. go JULY 1949

THE PARMENIDEAN DOGMA

PROFESSOR W. T. STACE

BY the Parmenidean dogma I mean the proposition that "something

cannot come put of nothing." If you like to add the other half of the

common statement it is that "something cannot become nothing."

But in this paper I shall be thinking mainly of the first proposition.

I call it the Parmenidean dogma because, although it may have

been implicit in much human thought before Parmenides, it was he,

so far as I know, who first made it explicit in the form of an abstract

metaphysical proposition.

Doubtless it originated in some such common experience as that

you cannot get a rabbit out of an empty top-hat, or, since there were

no top-hats in the days of Parmenides, whatever experience corre-

sponded thereto. You cannot get blood out of a stone, you cannot take

the breeches off a highlander, you cannot take money out of an

empty wallet, all these common experiences seem to illustrate the

principle. If anything appears suddenly on the scene, apparently

from nowhere, you ask: where did it come from? It must have been

somewhere all the time. It couldn't have come out of nothing. Just

as the common experiences of stones which are hard and grey, or

leaves which are green and soft, gave rise to the metaphysical concept

of substance, so these other common experiences gave rise to the

Parmenidean dogma. Thus common-sense truths are rashly erected

into universal metaphysical principles of all being. They harden into

dogmas. They solidify into prejudices so deep that in a little while

men say that anything which contradicts them is "inconceivable."

They then become fetters on the human mind prohibiting its advance,

till someone breaks through. This was the history of Euclidean

geometry, as everyone now knows. It was "inconceivable" that two

straight lines should enclose a space, till it was found in Riemannian

geometry that they do.

195

PHILOSOPHY

First, I should like to illustrate the way in which the Parmenidean"

dogma has moulded all European thought,fromthe time of its author

down to the present day. There is scarcely a branch of our common

thinking, or of science, or of philosophy which does not show its

influence. I think that a complete history of the idea, showing how

it has interwoven itself with our culture, fashioned and determined

our entire attitude to the world, would be a fascinating project. Of

course, I cannot undertake anything of that sort here. I will briefly

note only a few of-its most obvious ramifications.

To begin at the beginning. Everyone knows how Parmenides

himself used it, namely, to deny the existence of becoming. Change

always involves the arising of something new, something which

wasn't there before, something therefore which has come out of

nothing. If an object changes from green to red, then the red has

come from nowhere, and the green has disappeared into non-existence.

And as this contradicts the dogma it cannot have happened. It

seems to a modern mind a simple reflection that as a matter of fact

things do change colour, and that therefore, if this contradicts the

dogma, there must be something wrong with the dogma. But this

did not occur to Parmenides, nor apparently to Mr. Bradley

who uses essentially the same argument to prove that change is

unreal.

After Parmenides, everyone knows that his principle determined

the course of subsequent pre-Socratic philosophy, Empedocles,

Anaxagoras, the Atomists. I will pass over that. The next high light

is Aristotle. Everyone knows about that, too. But it is worth a

moment's reflection. Aristotle, as we know, believed he had "solved",

the problem of change—a problem artificially created by the dogma

and otherwise non-existent—by inventing the categories of potenti-

ality and actuality. The rabbit was, by means of these categories,

successfully produced out of the top-hat. This was very awkward

because we had just looked into the top-hat and seen that the rabbit

was not there. There is only one solution. The rabbit was in the hat

all the time. But it wasn't an actual rabbit. It was a potential rabbit.

That is why we couldn't see it when we looked. Potential rabbits are

invisible. In the same way chickens are able to come out of eggs

because they were there all the time, potentially; and oak trees are

able to come out of acorns because they were there all the time,

potentially. You may examine eggs and acorns with the most

powerful microscopes, including electron microscopes, and never find

chickens or oak trees inside them. But this again is because potential

chickens and oak trees are invisible.

We need only reflect on the enormous influence exercised by

Aristotle's concept of potentiality on subsequent thought, in

Aquinas, through the Middle Ages, and down to the present day, to

196

THE PARMENIDEAN DOGMA

see how the Parmenidean dogma has fashioned philosophy. It was

Parmenides who was responsible for potentiality.

Let us glance now at the influence of the dogma in science. Clearly

it produced the scientific maxims of the conservation of matter and

the conservation of energy. These ideas are not empirical generaliza-

tions. They are simply a priori deductions from the dogma. It is

true that no one has ever seen a piece of matter created or annihilated.

So that the conservation of matter has the basis in experience that

it agrees with common observation. It agrees with our observations

on rabbits and the breeches of highlanders. This, as I said before, was

what must have suggested the dogma in the first place. But it is

plain that these observations are an entirely insufficient basis on

which to found a universal principle about the nature of matter

throughout the universe. It is plain that scientists supposed that

matter could neither be created nor destroyed because they supposed

it inconceivable that something could come out of nothing or go into

nothing.

The same is true of the conservation of energy with one extremely

important difference. In this case the principle is not in the least

supported by common observation. On the contrary it is flatly

contradicted by our experience. If you throw a stone up on to a roof,

and it lodges there, you see kinetic energy completely disappearing

out of the world, disappearing into nothing. It was "there"—to use

the vulgar expression—when the stone was in motion on its upward

journey. It ceased to exist when the stone came to rest on the roof,

If a week later the wind blows the stone off the roof and it falls to

the ground energy appears again, out of nothing. Oddly enough, it

is the same quantity of energy which existed when the stone was on

its upward journey. What happened to the energy during the week's

interval? If you consult experience, observation, the answer is that

it had gone out of existence altogether. But this does not square with

dogma. Therefore the scientist invented the fiction of potential

energy—Aristotle's Parmenidean concept—to make it square. Not

only is this concept supported by no evidence whatsoever, but it is

in this case even flatly self-contradictory. For potential energy simply

means energy which is not now energizing. It is non-energetic energy.

In recent physics the separate principles of the conservation of

matter and the conservation of energy have apparently disappeared

—because it is now said that matter turns into energy and energy

into matter. But still following the Parmenidean dogma, they have

been replaced by the single principle of the conservation of matter-

energy.

The dogma also appears to be responsible for a conception which is

universal alike in our common-sense thinking, our science, and our

philosophy. This is the concept of form and matter. We suppose

197

PHILOSOPHY

that two quite different things are really, in spite of their difference,

the same thing, because one is a different form of the other or because

they are both forms of something underlying. Another variant of the •[

same idea is the notion of "aspects." There are supposed to be

different aspects of the same thing. An empiricist, though he may

admit that such ways of talking are convenient, cannot admit that

they possess truth. For if you say that A and B are two forms of one

thing, then either this one thing is an underlying substratum which

is unempirical; or you must mean that the one thing is A itself or

B itself. But if you say that A is a form of something which is by

hypothesis different from it, namely B, you are talking nonsense.

Red, for instance, cannot be a form of green.

Yet we use this category of form everywhere. Diamond and

charcoal, palpably different things, are said to be forms of carbon.

Heat, light, and electricity are said to be different forms of energy.

How, we may ask, is this the result of the Parmenidean dogma? It

is so for the following reason. Empirically what is observed in the

cases just mentioned is this. The charcoal disappears into nothing,

and the diamond appears from nowhere. The heat disappears out of

existence, and the light Comes out of nothing. The fact that equi-

valences can be set up, so that if heat is replaced by light, the light

can be again replaced by the original amount of heat, in no way affects

this. That is simply part of the. regularity and orderliness in the

changes of the world. But these observed facts contradict the

Parmenidean dogma. Therefore we say that the heat has never gone

out of existence, it has existed all the time, but in another form.

The category of form in this case does the same work as the category

of potentiality in the case of the stone thrown up to the roof. And the

one is as much a fiction as the other. And both fictions have been

developed in our culture in order to square observed facts with the

Parmenidean dogma.

To turn back now from science to philosophy we may briefly note

a few of the other major influences of the dogma. First, it is the basis

of the view, widely held by various philosophers in different times

and countries, that a cause and its effect are identical. We may call

this the identity theory of causation. Since, if all effects were com-

pletely and literally identical with their causes, there would be no

such thing as change in the world—a result which would be much

appreciated by Parmenides, but which most of us cannot accept—

the identity theorists have to say that the effect is only another

"form" of the cause. The Parmenidean origin of the identity theory

thus reveals itself at once. It is supposed that the effect must be

identical with the cause because otherwise we shall have to admit

that something has come to exist in the effect which was not in

existence before, i.e. that something has come out of nothing.

198

THE PARMENIDEAN DOGMA

A less radical variant of the same theory is that cause and effect,

though they may not be identical, must at least be alike. This is

flatly contradicted by experience since, for example, lightning is

almost totally unlike its effect, thunder, one, being a visual and the

other an auditory phenomenon. Of course, the theory cannot be

made even clear in view of the fact that resemblance is a matter of

degree, so that it is impossible for the theory to say how much

resemblance between cause and effect is required. Probably every-

thing in the universe resembles everything else in some of its charac-

teristics, however much it may be unlike them in others.

This theory, clearly an offshoot of the Parmenidean dogma, is at

the bottom of the baseless objection to Cartesian dualism, that it is

"inconceivable" that mind and matter, one spatial, the other non-

spatial, could influence one another. Why not? Evidently because

they are, on Descartes' account, so very unlike. Thus we see that

Parmenides has a finger even in the pie of the body-mind problem.

Another variant of the influence of the dogma on theories of

causation is Descartes' statement that an effect cannot contain more

"reality" than was contained in its cause. Descartes' question,

"For whence could the effect derive its reality, if not from its cause ?"

is the old question, where did the rabbit come from?

This brings me to the last example I have time to discuss. This is

an idea which is, so far as I can see, one of the main props of what is

known as absolute idealism. The idea is that the higher cannot come

out of the lower. Spiritual values, such as beauty and goodness,

cannot come out of nothing, and thfe would be involved if they came

out of what is lower than themselves. Therefore they must have

always been in existence. They must be eternal. Indeed, on the

Parmenidean view everything must be eternal, since nothing can

ever come into existence. This is in fact the theory of absolute

idealism, since it holds that if anything does come into existence it

cannot be real, but is only an appearance. From this point of view

absolute idealism is in all its expanse nothing but a vast elaboration

of the Parmenidean dogma. But I was talking about its special

theory of value. And I return to that. Beauty or goodness may appear

to arise out of something lower than themselves. But this is im-

possible. There must therefore be an eternal and timeless source of

values. This, of course, is the Absolute.

You point out that all this contradicts plain facts. Does not the

beauty of the rose arise out of the dirt at its roots? Indeed, if you

add dung, which from a value point of view is even more con-

temptible than plain dirt, the beauty of the rose enormously increases.

The facts of evolution, too, contradict the statement that the higher

cannot come out of the lower. For although I am aware that it is

not part of the scientific theory of evolution that man is higher

199

PHILOSOPHY

than an amoeba; and though I am also aware that it is extremely

difficult to say exactly what we mean by such terms as higher and

lower; yet in spite of this I think we must hold that a man is in some

sense higher than an amoeba. Again, are not geniuses notoriously

often the children of comparatively ordinary parents?

To all this the idealist answer is that the pre-existent values in the

Absolute are invisible like the potential rabbit. For this is what is

meant by saying they are transcendental. Transcendental means not

phenomenal; and not phenomenal means not visible. Of course, if

you give up the Parmenidean dogma, the whole of this cloud-land of

reveries disappears into thin air.

It is now time to look at the dogma itself and see what is to be said

about it. Those who maintain it must hold either that it is an empirical

generalization or that it is a necessary truth. In spite of the fact that

experience, the common experiences with rabbits and bighlanders'

breeches, must have originally suggested it, it cannot possibly be an

empirical generalization. For as we have seen, observed facts con-

tradict it right and left. Therefore it must be a necessary truth, if

it is a truth at all. And I think as a matter of fact it has always

been so regarded by its supporters. Parmenides himself must have

thought this, since he used it to contradict experience. This is an

interesting reflection. For it shows that an idea, even before it has

ever been stated in an abstract form by a philosopher, may already

have hardened in men's minds into a prejudice so deeply rooted

that the philosopher, when he lights upon it, supposes that the

opposite of it is "inconceivable," and so mistakes it for an a priori

proposition. Descartes too evidently regarded his form of it as an

a priori truth which he could therefore take into his system as an

axiom. And I remember to have been astonished to hear a well-

known philosopher in a public lecture at Princeton say without a

blush that to suppose that something could come out of nothing

would be a logical self-contradiction, i.e. that the Parmenidean dogma

is an analytic truth.

I say "astonished," because any competent student of philosophy

ought to know that Hume finally and decisively refuted the view

that it is an analytic truth. This was not a mere opinion of Hume's

to which another philosopher is entitled to oppose an opposite

opinion. It was the definitive settlement of the question.

I am not referring to Hume's famous treatment of the idea of

necessary connection. I should not put his view on that question as

higher than an opinion, although I happen to agree with it. The

question we are discussing has nothing at all to do with necessary

connection. I am referring to Section 3 of Part 3 of the Treatise

entitled "Why a cause is always necessary." Hume's arguments there

are entirely independent of his views on necessary connection and

200

T H E P A R M E N I D E A N DOGMA

will remain valid even if we reject those views. It is true that Hume

\ does not discuss the proposition "something cannot come out of

nothing." What he discusses is the proposition "whatever begins to

exist must have a cause of existence." I will call this the causal

proposition. I cannot here discuss its exact logical relationship to

the Parmenidean dogma, but will say only that if Hume's proofs

are valid in regard to the one proposition they are valid in regard to

the other. The relevant considerations are identical in the two cases.

Hume produces several refutations of the view that the causal

proposition is an analytic truth. I will reproduce only one of these.

He points out that we can easily imagine—he is using the word in

the strict sense of having a mental image of—we can easily imagine

something coming into existence without a cause. Thus you can

easily imagine a billiard ball suddenly appearing on the table here,

literally beginning to be, without any cause, or if you like, coming

from nowhere. In fairy tales we often do, on the invitation of the

author, imagine such events. Now it is impossible to have an image of

something which is self-contradictory. For instance, you cannot

imagine a round square. Therefore the fact that you can imagine a

. thing or event proves that it is not self-contradictory. Therefore since

you can imagine a thing coming into existence without a cause, this

i proves that it is not self-contradictory. Hence the causal proposition

cannot be an analytic a priori truth.

. Hume might have pointed out that the impossibility of imagining

=? a self-contradictory thing is only a particular case of the more general

j truth that you cannot have any kind of direct or immediate experi-

\ ence of a self-contradictory thing. For instance, a round square could

| not form a part of even a hallucinatory experience, much less of a

^ sense-experience. It is odd that Mr. Bradley did not notice this. If

he had, he would not have written his book. For if it were really the

i case that space, time, motion, etc.," are self-contradictory, this would

| not only prove, as he thought, that they cannot be real; it would

I • prove that they cannot even appear or be experienced in any way.

That they are self-contradictory proves, he thinks, that they are

appearances. What it would actually prove, if it were true, would be

that they could not possibly be appearances, not even hallucinatory

appearances. This oversight is the more odd in view of the long history

of the laws of logic since the time of Aristotle. The law of contradic-

tion has always been regarded as forbidding self-contradictory beings

or events in the common world of existence, in what idealists call

the phenomenal world, not in the world of transcendental reality.

That you cannot both have your cake and eat it is a plain statement

about the world of appearances, about phenomena, not about

noumena. If Bradley were right in thinking that self-contradictory

fc- things can exist in the world of appearance, but not in the world of

201

PHILOSOPHY

reality, then it ought to be possible both to eat your cake and have

it—on earth, though not apparently ki heaven.

To Hume's proof I will add another of my own. When it is said

that a thing is self-contradictory, this is of course elliptical. Things

cannot contradict themselves or one another. Only propositions can.

So when it is said that a thing is self-contradictory what is meant is

that two contradicting propositions follow from the assertion of its

existence. Therefore if anyone says that something is self-con-

tradictory we ought always to ask him to set out the two contradict-

ing propositions. It follows that, if a thing or event can be completely

described without remainder in a set of propositions none of which

contradicts another one, then the thing or event cannot be self-

contradictory. Now suppose that a thing or event x comes into

existence out of nothing, passes from non-existence to existence, at

time t. This fact can be exhaustively described in only two proposi-

tions, which are (i) that x did not exist before time t, and (2) that *

existed after time t. These propositions do not contradict one another

since they refer to different times. If it were said that x both exists

and does not exist at the same time, this would be self-contradictory.

But to say that it exists at one time, but not at another, contains no

contradiction. Therefore x coming into existence out of nothing is

not self-contradictory.

This argument, can be applied to the causal proposition in the

following manner. Suppose that x came into existence at time t

without a cause. This can be completely described in three proposi-

tions, namely, (1) that x did hot exist before time t, (2) that x existed

after time t, (3) that before time t there was no event which stood in

the causal relation to x. No one of these three propositions contradicts

another one. Therefore the supposition is not self-contradictory.

Thus it is certain that the Parmenidean dogma is not an a priori

analytic truth. The only remaining possible defence of it is that it is

an a priori synthetic truth. This view will not find much favour

nowadays. But this is not decisive against it since current denials

of a priori synthetic truths, might be mistaken. What is decisive,

however, is the following. If there are any a priori synthetic proposi-

tions, they must have the character of necessity which must be

intuitively apparent. For instance, A. C. Ewing holds that the

proposition "a surface cannot be red all over and green all over at

the same time" is a synthetic a priori truth. I will not discuss whether

he is right. But one can see at once that the proposition is at any

rate a necessary one. It bears necessity intuitively on its face. The

only question, of course, is whether it is analytic or synthetic. Thus

if the Parmenidean dogma is an a priori synthetic truth, it must

have the character of being intuitively necessary. But it does not.

No such necessity can be perceived in it. Therefore it is not a synthetic

202

T H E P A R M E N I D E A N DOGMA

a priori proposition. It is true that the necessity of an a priori

proposition may not be immediately intuitable. This is the case with

advanced propositions in mathematics, which are nevertheless a priori

truths, though analytic. But in that case their necessity can always

be shown by a series of steps the necessity of each of which is imme-

diately intuitable. This means that they can be proved. Now no one

has ever suggested that the Parmenidean dogma is of that kind,

that it is reached or reachable by a series of demonstrable steps.

Obviously the claim is that its necessity is immediately intuitable.

But this is simply not the case. If anyone claims that it is, I think

it is certain that his case is like that of a man who might say that the

proposition "the earth is flat" has for him the character of imme-

diately intuitable necessity. I do not know how to argue with such

a person. But it is quite clear that what has happened is that he has

mistaken a psychological feeling of certainty, such as is derived from

a deep-rooted prejudice, for a logical necessity.

We reach the result that the Parmenidean dogma is baseless. What

then? It certainly follows that a vast amount of philosophy based on

it must be rejected—I will not go over the list of such philosophies

again. It does not follow that some of the ideas based on it may not

be useful. Perhaps potential energy may be a useful fiction. It is

necessary if the principle of conservation is to be preserved. And that

principle, though it cannot claim to be an absolute truth, is doubtless

a valuable methodological assumption.

But in general our picture of the world will be changed—and

changed evidently in the direction of a more empirical philosophy.

We shall not invent hidden substances underlying the changes of

things in order to preserve the things from going in and out of

existence. We shall not invent a hidden mysterious energy which

underlies heat, light, and electricity. We shall say that the principle

that they are all "forms" of energy means only that when a given

amount of motion disappears and is replaced by a given amount of

heat, these are equivalents in the sense that the original amount of

motion can be made by suitable means to appear again and displace

the heat.

Finally, it seems to me that recent physics supports the view I am

taking. An electron is said to jump from one orbit to another, without

traversing the intervening distance. To use an illustration of White-

head's, this is as if we should say that an automobile travelling at

thirty miles an hour really appears at one milestone, remains there

for two minutes, disappears from that point and instantaneously

reappears at the next milestone, without travelling the intervening

mile, remains for two minutes at that milestone, and so throughout

its course. This view of the electron traverses the Parmenidean

dogma. For it is merely a matter of language whether we say that

203

PHILOSOPHY

the electron which appears in the new orbit is the "same" electron

which disappeared from the old orbit or whether we say that the

first electron has ceased to exist and a new one has come into

existence. The two statements are equivalent but employ different

definitions of the word "same." Hence the statement that one electron

has ceased to exist and another has been created out of nothing is

true. Yet it contradicts the Parmenidean dogma. I do not think

this view of the electron in modern physics could have been put

forward unless physics had now tacitly given up the Parmenidean

dogma.

Again action at a distance must, on our view, be conceived as

possible. For there is no contradiction in supposing that a cause

happens here and that its effect takes place a million miles away with

no intervening chain of events. It may be that it is not necessary for

the physicist at present to assert that such a thing ever does take

place. He may prefer to stick to his view that action at a distance

does not occur. But the rejection of the Parmenidean dogma will

mean that his mind is perfectly open to admit action at a distance

if ever the evidence should point to it. He will not say that it is

"impossible" or "inconceivable," though he may say that so far as he

at present knows it does not occur.

In general the moral is: anything whatever can happen—anything

except round squares, two twos making five, or other self-contradic-

tions. It is simply a matter of evidence. I have sometimes been asked

what is the value of empiricism. Sometimes I am afraid it is used to

rule out possibilities. Sometimes it appears as a narrowing influence.

But its true function is to free the mind from prejudices, to free us

from the bondage of supposing that our prejudices are laws of the

universe. Instead of narrowing our view-point, it should open our

minds and our imaginations to the possibilities of new paths and

hitherto undreamed of progress in knowledge. It should strike off

many ancient fetters from our minds.

204

You might also like

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (590)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (540)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (401)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5813)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (844)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (822)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (897)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (348)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1092)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Simplicius - On Aristotle Physics 1.1-2 (Ancient Commentators On Aristotle) - Bloomsbury Academic (2022)Document267 pagesSimplicius - On Aristotle Physics 1.1-2 (Ancient Commentators On Aristotle) - Bloomsbury Academic (2022)Bruno ThiagoNo ratings yet

- Curriculum Vitae FinalDocument2 pagesCurriculum Vitae Finalapi-335073698No ratings yet

- Spontaneous Generation and Generation by Chance (Outline)Document7 pagesSpontaneous Generation and Generation by Chance (Outline)Bruno ThiagoNo ratings yet

- EmpédoclesDocument25 pagesEmpédoclesBruno ThiagoNo ratings yet

- The Powers Metaphysic Reviews Notre DameDocument1 pageThe Powers Metaphysic Reviews Notre DameBruno ThiagoNo ratings yet

- Individuals Form Movement From Lambda ToDocument17 pagesIndividuals Form Movement From Lambda ToBruno ThiagoNo ratings yet

- Parmenides Dilemma A N D Aristotle'S Way O U T: University of KansasDocument7 pagesParmenides Dilemma A N D Aristotle'S Way O U T: University of KansasBruno ThiagoNo ratings yet

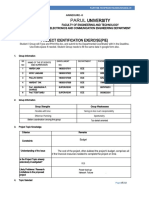

- Parul University: Project Identification Exercise (Pie)Document2 pagesParul University: Project Identification Exercise (Pie)Harsh Jain100% (1)

- Lesson 1.1 Definition and Division of Literature (REVISED)Document24 pagesLesson 1.1 Definition and Division of Literature (REVISED)Jennifer OriolaNo ratings yet

- Assignment - Developmental TheoriesDocument7 pagesAssignment - Developmental TheoriesKewkew Azilear100% (1)

- Lecture01 CE72.12FEM - Course IntroductionDocument26 pagesLecture01 CE72.12FEM - Course IntroductionRahul KasaudhanNo ratings yet

- Advertisement For Faculty Recruitment Vol - 11 December, 2023Document13 pagesAdvertisement For Faculty Recruitment Vol - 11 December, 2023vishnudocNo ratings yet

- CV Deddy Setiawan RF OptimDocument3 pagesCV Deddy Setiawan RF OptimSatrya Teguh SangkutiNo ratings yet

- Pepperdine Dissertation SupportDocument5 pagesPepperdine Dissertation SupportHelpWithPaperWritingBuffalo100% (1)

- Icse Resul 20190508081952103Document31 pagesIcse Resul 20190508081952103Aditya SrivastavaNo ratings yet

- Agaw Family (Kemant, Khamtanga, Qwarenya) : David Appleyard, SOASDocument3 pagesAgaw Family (Kemant, Khamtanga, Qwarenya) : David Appleyard, SOASKouame AdjepoleNo ratings yet

- (13-04-20) Class 4 Maths Week 5thDocument5 pages(13-04-20) Class 4 Maths Week 5thAdil Shahzad QaziNo ratings yet

- Problem of Child Labour in India and Its Causes:: With Special Reference To The State of AssamDocument14 pagesProblem of Child Labour in India and Its Causes:: With Special Reference To The State of AssamRaajdwip VardhanNo ratings yet

- Thesis On Indian Education SystemDocument8 pagesThesis On Indian Education Systemgbxwghwb100% (2)

- FDP - Brochure & ScheduleDocument2 pagesFDP - Brochure & Scheduleavinash dNo ratings yet

- Praveen Kumar Singh: WWW - Depintegraluniversity.inDocument2 pagesPraveen Kumar Singh: WWW - Depintegraluniversity.inLong Lasting FeelingsNo ratings yet

- Comparative and Superlative AdjectivesDocument4 pagesComparative and Superlative Adjectivesفاطمة الزهراءNo ratings yet

- Sr. Kg. Summer Holiday Assignment 2022Document8 pagesSr. Kg. Summer Holiday Assignment 2022Kinnari VahiaNo ratings yet

- Brian Josephson ThesisDocument6 pagesBrian Josephson Thesiskarenwashingtonbuffalo100% (1)

- Chapter IiDocument3 pagesChapter IiAsyana Allyne B DueñasNo ratings yet

- Makalah Bahasa Inggris Kelompok 6Document10 pagesMakalah Bahasa Inggris Kelompok 6Vinasyasholafaananda AnandaNo ratings yet

- 03 Kianian 2Document7 pages03 Kianian 2awaluzzikryNo ratings yet

- Tiếng Anh 10 Friends Global - ppt - unit 1 - lesson 1cDocument29 pagesTiếng Anh 10 Friends Global - ppt - unit 1 - lesson 1cTrang EmilyNo ratings yet

- LSBU Immigration Information Form v1Document3 pagesLSBU Immigration Information Form v1kudzanaiNo ratings yet

- Ksa Design Thinking For HR Professionals 2020 PDFDocument5 pagesKsa Design Thinking For HR Professionals 2020 PDFHamid OtaifNo ratings yet

- Nihana Sherin P 11 16 2023 11 48 22 AMDocument2 pagesNihana Sherin P 11 16 2023 11 48 22 AMNihana sherinNo ratings yet

- Final Quiz Ogl 220Document4 pagesFinal Quiz Ogl 220api-686097813No ratings yet

- Materials Chemistry A: Journal ofDocument11 pagesMaterials Chemistry A: Journal ofBhabani Sankar SwainNo ratings yet

- Perguruan Islam Mathali'Ul Falah: Panitia UjianDocument2 pagesPerguruan Islam Mathali'Ul Falah: Panitia UjianMuhammad Riza Nor RohmanNo ratings yet

- Mechanics of Deformable BodiesDocument8 pagesMechanics of Deformable BodiesCllyan ReyesNo ratings yet

- ConnectPay UABDocument17 pagesConnectPay UABAhmer HussainNo ratings yet