Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Benítez Rojo Ortiz Postmodern

Uploaded by

Karen BenezraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Benítez Rojo Ortiz Postmodern

Uploaded by

Karen BenezraCopyright:

Available Formats

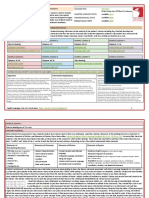

Fernando Ortiz and Cubanness: A Postmodern Perspective

Author(s): ANTONIO BENÍTEZ-ROJO

Source: Cuban Studies , 1988, Vol. 18 (1988), pp. 125-132

Published by: University of Pittsburgh Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24486958

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Cuban Studies

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.179 on Thu, 05 Nov 2020 20:35:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

ANTONIO BENÎTEZ-ROJO

Fernando Ortiz and Cubanness:

A Postmodern Perspective

ABSTRACT

This article claims that Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azuc

nando Ortiz presents a Caribbean response to the question of post

After demonstrating that Ortiz deliberately rejected a dialectical

order to speak of Cubanness through tobacco/sugar relations, this

out that in the framework set forth by Ortiz, the rumba, carnival

rituals, theater, and poetry all appear as modes for acquiring and

ing knowledge. The introduction of that poetic element is precis

characterizes Caribbean postmodernity.

RESUMEN

Este articulo argumenta que Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el a

Fernando Ortiz constituye una respuesta caribena a la cuestiôn

modernidad. Luego de demostrar que Ortiz deliberadamente rechaz

foque dialéctico con el fin de hablar de cubanidad mediante las

tabaco/azucar, el articulo sefiala que en el marco desarrollado por O

rumba, el carnaval, los rituales afro-cubanos, el teatro y la poesia a

como modos de adquirir y comunicar conocimiento. La introducciô

elemento poético es precisamente lo que caracteriza a la post-m

caribena.

In one of his last interviews, Fernand Braudel was asked what differ

ences he saw between the concepts of interdisciplinarity and intersci

ence. Braudel responded: "L'interdisciplinarité c'est le mariage légal de

deux sciences voisines. Moi, je suis pour la promiscuité généralisée. I

believe that Braudel's answer is not only in keeping with his work, and

with the approach of the so-called "nouvelle histoire," but also with the

multidisciplinary pluralism currently observed in the works of well

known humanists and scientists.

This kind of analytical approach, in which observations common to

the most varied disciplines intervene, is quite characteristic of the

present era. It is becoming increasingly difficult to accept, in their

entirety and without skepticism, the postulates of any one discipline,

125

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.179 on Thu, 05 Nov 2020 20:35:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

126 Antonio Benîtez Rojo

especially in terms of its legitimacy for studying a given ph

its own. If, for example, we wish to study the relations

tion owners and slaves in some part of the Caribbean, it

that we shouldn't limit our analysis by using a strictly

nomenclature that alone would no longer suffice to study th

of those relations. We would also have to resort to supp

bularies suitable to the study of those spaces occupied by

ity, power, knowledge, and culture, and from perspecti

that they would range from psychoanalysis to feminism

literary theory to history.

We are entering an era that has begun to be called post

industrial, postideological, or simply the era of the

considering the agricultural and industrial revolutions as

changes previously experienced by humanity. If we exam

definition, we see that postmodernity stems from its r

cepting the discourse of any discipline as legitimate, sinc

legitimacy rests upon the arbitrary act of accepting as it

"center" or "origin" any one of the great narratives of th

"the dialectics of Spirit, the hermeneutics of meaning, th

of the rational or working subject, or the creation of wea

course, those fables, in turn, must base their legitim

principles of "truth" and "justice" which we hesitate

absolutes, but rather as the product of skillful manipul

postmodernity is presented as an attitude divorced from

therefore, from prophetic destinations, an attitude that reje

ics and scatological categories. In postmodernity, there ca

single truth, but rather many small, practical, and mome

truths without origins or destinations, shifting truths, p

provisional truths.

Now then, assuming that we accept that the industrial r

not solved the problems of the West, the East, and the Third

the ideologies offered as universal remedies or infallible

leave much to be desired when one attempts to apply the

such as "good," "unity," "positive,"and "justice" do notex

themselves; that science, and even mathematics, have mu

with language and that history is much more literature t

else; assuming, finally, that we choose to live in a postm

sion—assuming all this, for what reasons and according t

are we to observe and arrive at conclusions about any gi

non taking place in the Caribbean, an archipelago th

reached modernity?

I am not certain whether this preamble is necessary

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.179 on Thu, 05 Nov 2020 20:35:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Fernando Ortiz and Cubanness : 127

consider Fernando Ortiz's Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azxicar

(The Cuban Counterpoint of Tobacco and Sugar), but it happens that

the book presents a Caribbean response to the question of postmodern

ity. In any case, if the reader were to reject Ortiz's position—a position

that I shall analyze shortly—that reader would not be alone. For exam

ple, in the critical bibliography included in the second edition of El

ingenio (The Sugarmill), Manuel Moreno Fraginals says the following

about Ortiz's book: "Many of his observations are brilliant and sugges

tive; other can not withstand the slightest critical analysis."3 Of course,

Moreno Fraginals is speaking from his position as a socioeconomic

historian of sugar, which implies a scientific as well as an ideological

truth. Those of Ortiz's observations that suit those truths are "brilliant

and suggestive"; those that do not are incapable of resisting "the slight

est critical analysis." This is the typical judgment of a modern social

scientist; the judgment of a specialized, authorized, and legitimized

voice. I say this with no irony intended; we all realize that El ingenio is

one of the most fascinating books produced by the literature of sugar.

But surely, so is Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azucar, especially

if it is not read exclusively as a socioeconomic study of tobacco and

sugar, but rather as a text dealing with Cubanness.

Naturally, it is impossible to undertake here a detailed analysis of

Ortiz's book, so I will limit myself to commenting briefly on some of its

traits, particularly those allowing for a postmodern reading. Perhaps the

first thing about the book that catches one's attention is its table of

contents. It has what appear to be two parts. One is titled exactly like the

book (The Cuban Counterpoint of Tobacco and Sugar), and the other

"Transculturaciôn del tabaco habano e inicios del azucar y de la escla

vitud de negros en América" (Transculturation of the Cigar and Begin

nings of Sugar and of Black Slavery in America).4 The second part

consists of twenty-five chapters, the first of which is entitled "Del

'contrapunteo' y de sus capitulos complementarios" (On the "Cuban

Counterpoint" and its Complementary Chapters). Upon reading this

first chapter, which offers certain explanations of the work, we immedi

ately ask why it wasn't placed at the beginning of the book, following

Bronislaw Malinowski's introduction and as a kind of author's preface.

We do not know what Ortiz would have replied, but one must conclude

that for him any judgment the author may pass upon his work, even if

only explanatory, should be read as yet another chapter of the book, and

not as an a posteriori, corrective, even repressive text bearing the

author's name or signed with just his initials or simply "The Author."

Ortiz's decision to place his opinions on his work within the text of his

work, and not in a note or a preface, points to several characteristics of

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.179 on Thu, 05 Nov 2020 20:35:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

128 : Antonio Benîtez Rojo

postmodern literary theory. One of these is the belief tha

reason for establishing a hierarchical relationship between

texts—a belief to which Ortiz seems to adhere when he includes this

unique chapter within the same category as chapter 6, which deals with

tobacco and cancer, or chapter 24, titled "De la remolacha enemiga"

(The Enemy Beet). Another characteristic of postmodern literary the

ory is to demythologize the concept of author, to erase the halo of

creator with which he or she is perceived by modern criticism. For the

critic studying the literary process from a postmodern perspective, far

from being a creator of words and worlds, the author is a kind of

technician whose trade is controlled by a preexisting practice or textual

discourse; the author is simply a writer. If such an opinion were held,

then a preface or author's note would lack sufficient author-ity to

warrant a separate space from the work written by the author, and,

therefore, an explanation could well appear as another chapter in the

book.

But let us see just what type of explanation appears in that first

complementary chapter:

Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azucar is an essay of schematic character.

It does not attempt to treat the subject exhaustively, nor does it pretend that the

economic, social and historical counterpositions pointed out between both

products of Cuban industry are all as absolute and clear-cut as they are often

presented in contrast. Socioeconomic phenomena are quite complex in their

historical evolution, and the multiple factors which determine them make them

vary widely in their trajectories, at times drawing them together due to their

similarities, as if they belonged to the same order, and at times separating them

due to their differences, until they appear antithetical. At any rate, essentially

the contrasts remain just as they have been pointed out.5

In my reading of this paragraph, I observe, first of all, that Contra

punteo cubano del azucar y el tabaco is not presented as a work which

has achieved its goal, but rather as a vehicle conscious of its insuffi

ciency, which "does not attempt to treat the subject exhaustively." In

other words, this is a text with no final destination that does not pretend

to arrive at the truth. Moreover, it is a text that is conscious of itself and

informs us that what we may interpret as truths are, rather, arbitrary

decisions employed for the sake of establishing the strategy of the

discourse. That strategy—we read—consists of rendering "absolute

and clear-cut" the "economic, social and historical counterpositions"

between tobacco and sugar, when, in fact, they are not so to that extent.

That brings us to what constitutes the heart of postmodern literary

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.179 on Thu, 05 Nov 2020 20:35:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Fernando Ortiz and Cubanness : 129

analysis: the questioning of the concept of "unity" and the disassem

bling, or rather unmasking, of the mechanism known as binary opposi

tion which, to a greater or lesser degree, supports the philosophical and

ideological structures of modernity. According to what we read here,

those concepts are mere appearances, adopted in their "historical evolu

tion" by socioeconomic phenomena. Indeed, these may be interrelated

because of their similarities, "as if they belonged to the same order," or

they may be separated "due to their differences, until they appear

antithetical." And that relativism is possible thanks to the "multiple

factors" intervening in the formation of said phenomena. Thus, binary

opposition is not a law, but rather a strategy of the discourse, since the

respective unities of the poles in conflict are not only apparent, but also

subverted by the presence of multiple factors—that is, by differences.

Finally, I examine the sentence "At any rate, essentially the contrasts

remain just as they have been pointed out." This is, indeed, a blunt and

straightforward statement that quite precisely defines the limits of post

modern analysis: nevertheless, in order to establish the postmodern

point of view, one needs analogies and oppositions. Therefore, there is

no alternative but to retain them, even if no longer as truths, but rather as

options with a strategic value that may be construed as yet another

example of the infinite interplay of possibilities.

Finally, to conclude with this unique chapter, I should like to point

out that the four-hundred-odd pages constituting the twenty-five com

plementary chapters are, as Ortiz tells us, footnotes to the eighty pages

of his essay. That, of course, is a serious textual transgression even

within the most tolerant limits of socioeconomic discourse, and draws

Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azucar ever closer to the discourse

of the novel.

Let us now take a quick glance at Ortiz's text. To begin with, it does

not seek its legitimacy in the discourse of the social sciences, but rather

in that of literature, of poetry, to be exact. One must bear in mind that

the text is based upon the controversy between Don Carnal and Dona

Quaresma—allegories of Carnival and Lent—which we read about in

Juan Ruiz's Libro de buen amor (The Book of Good Love). After briefly

describing that fourteenth-century work in his first paragraph, Ortiz

declares:

Perhaps the famous controversy imagined by that great poet [Ruiz] is the

literary antecedent that now allows us to personify black tobacco and fair

skinned sugar, and make them appear in this fable narrating their contradic

tions.6

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.179 on Thu, 05 Nov 2020 20:35:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

130 Antonio Benîtez Rojo

Further on, he adds:

But, moreover, the contrasting parallelism of tobacco and sugar

. . . that it goes beyond merely social perspectives, reaching th

poetry. . . . After all, that dialogistic genre that applies the dial

dramatic art was always typical of the naive muses of the peo

music, dance, song and theater. Let us remember its most florid

in Cuba in the antiphonal praises of the liturgy, both by whites

the erotic and danced controversy of the rumba, and in the ver

points of country peasants and Afro-Cuban dandies.7

Those, then, are the promiscuous origins of Contrapunte

tabaco y el azùcar: Juan Ruiz's Libro de buen amor (quote

throughout the text), the antiphonal rituals of the Catho

Cuban liturgies, music in general and the ' 'rumba" in parti

songs, popular theater, and, of course, the social sciences

over, the text is not presented as a monologistic, patriarch

centric narrative, but rather as a dialogic and acentric fa

plurality of voices and rhythms one may perceive the mo

ciplines and the most irreconcilable ideologies. I would say

above all, a pagan text—pagan in the same fashion as the

bisa del Santo Cristo del Buen Viaje (Kimbisa Order of the

of the Safe Journey). This is a Cuban cult founded in the

that accepts Christ, the Virgin Mary, and the Catholi

without relegating to inferior positions the nganga of th

"nkisi"ofthe Abakuâorthe "orisha"ofthe Lucumi. Or it is

fashion of the Shango cult, born on the island of Trinida

more than sixty gods, or great spirits, cdMtàpowers by its bel

of these, over thirty may be identified with African deiti

ruba; about twenty are of Catholic origin, that is, hagiogr

—Samedona, Bogoyana, and Vigoyana—are of Indo-Americ

having reached Trinidad through the Guianas; two others

Mahabil—were brought to the island by indentured servant

and one, called Wong Ka, comes from China. Moreover, in

cult there are also elements derived from the Baptist chur

European witchcraft.

I have the impression that this transgressive and highly

space is precisely what, according to the modern perspect

withstand the slightest critical analysis." And yet, as I see

is the most representative of Cubanness, of Caribbeannes

tural sense of the term.

Returning to Ortiz's book, it is evident that the presence of tobacco

and sugar in the text does not refer exclusively to those products in the

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.179 on Thu, 05 Nov 2020 20:35:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Fernando Ortiz and Cubanness : 131

narrow sense of the word. Tobacco and sugar possess a metaphoric

value that applies to blacks and whites, to slaves and plantation owners,

to art and technology, to small rural holdings and large estates, to

national and foreign capital, to independence and dependence, to agri

cultural and industrial diversification as opposed to single-crop and

single-product economies, to sovereignty and foreign intervention, to

free labor and slave labor, to the discourse of resistance and the dis

course of power, to desire and repression. And all of that, together, is

Cubanness, Caribbeanness. Tobacco is the carnival, the celebration,

the dancing, the drum, the giddiness, sensuality; it is the reign of Don

Carnal in Libro de buen amor, the sphere of art, imagination, and all that

is poetic. On the other hand, sugar alludes to logos, the law, theoretical

knowledge, discipline, and punishment; it is the domain of Lent, of

production and ideology; it is the space offered as the center, the origin,

the destination. And yet, Cubanness is not constituted by sugar alone,

nor by tobacco, but rather by the counterpoise of tobacco and sugar.

Now, it is interesting to note how Ortiz avoids the idea of a binary

opposition between the referent fields allegorized through tobacco and

sugar. To begin with, he uses the term counterpoint, which returns us to

baroque music—that is, to a sonorous architecture of excessive and

acentric character. More concretely, he refers us to a musical form in

which the voices do not oppose each other in terms of binary opposition,

but rather unfurl in parallel fashion in perpetual evasion, each one

progressing under the provocative impulse of the other. Hence the

denomination offugue given to the most representative genre of baroque

music. Ortiz refers to this dialogic form in terms of parallel counterposi

tion, not of opposition.

I suppose that a postmodern philosopher—I am, of course, referring

to an intellectual educated in Europe or in the United States—would

have no objection to accepting this curious form that rejects binary

opposition and establishes a kind of coexistence. And, of course, he

would be highly impressed by Ortiz's show of ideological and multi

disciplinary promiscuity when speaking about Cubanness. What is

more, he would be quite pleased with Ortiz's critical attitude toward

machinery; it is a typically postmodern attitude in the sense that it does

not seek a lost paradise in a mythical era of the preindustrial past, but

rather limits itself to pointing out the monotony and flatness inherent in

industrial pragmatism, both in relation to Western capitalism and Soviet

socialism. Lastly, I believe that the contingent postmodern philosopher

we have alluded to would approve Ortiz's final gesture of naming

alcohol the resulting sound (or metaphor) of this Cuban counterpoint,

since alcohol can not be taken as a possible synthesis of tobacco and

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.179 on Thu, 05 Nov 2020 20:35:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

132 : Antonio Benîtez Rojo

sugar but rather as a signifier whose ' 'excessiveness" provid

for both voices to perform their parts. But at the same time, I

philosopher would be puzzled by a perspective not envis

arguments. This is that in the framework of "generalized p

set forth by Ortiz, Afro-Cuban beliefs, along with the "rum

carnival, should appear as forms of knowledge as valid as t

mon to theoretical knowledge. The introduction of that poet

so familiar to us Antilleans, is precisely what would charac

modernity seen from a Caribbean viewpoint.

NOTES

This article, translated by Jaime Martinez-Tolentino, was presented at the

ence on Caribbean Culture and Identity, Woodrow Wilson International Cent

ington, D.C., March 1987.

1. François Ewald and Jean-Jacques Brochier, "Une vie pour l'histoire," M

Littéraire 212 (1984): 22.

2. Jean-François Lyotard, The Postmodern Condition: A Report on Kno

(Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984), pp. xxiii-xxv.

3. "Muchas de sus observaciones son brillantes y sugerentes; otras mu

resisten el menor anâlisis critico" (Manuel Moreno Fraginals, El ingenio (

Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 1978], 3:246).

4. Fernando Ortiz, Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azucar (1940; rpt. C

Biblioteca Ayacucho, 1978).

5. "El Contrapunteo cubano del tabaco y el azucar es un ensayo de carâcte

mâtico. No trata de agotar el tema, ni pretende que las senaladas contrap

econômicas, sociales e histôricas entre ambos productos de la industrie cuba

tan absolutas y tajadas como a veces se presentan en el contraste. Los fenome

nômico-sociales son harto complejos en su evoluciôn histôrica y los multiples

que los determinan los hacen variar grandemente en sus trayectorias, ora acerc

entre si por sus semejanzas como si fuesen de un mismo orden, ora separândolos

diferencias hasta hacerlos parecer como antitéticos. De todos modos, en lo susta

mantienen los contrastes tales como han sido sefialados" (p. 91).

6. "Acaso la célébré controversia imaginada por aquel gran poeta sea pre

literario que ahora nos permitiera personificar el moreno tabaco y la blanconaz

y hacerlos salir en la fabula a referir sus contradicciones" (p. 11).

7. "El contrastante paralelismo del tabaco y el azucar es tan curioso . .

mâs alla de las perspectivas meramente sociales para alcanzar los horizon

poesia. ... Al fin, siempre fue muy propio de las ingenueas musas del pue

poesia, mùsica, danza, canciôn y teatro, ese género dialogistico que lleva hast

dramâtica la dialéctica de la vida. Recordemos en Cuba sus manifestaciones mâs

floridas en las preces antifonarias de las liturgias, asi de blancos como de negros, en la

controversia erotica y danzaria de la rumba y en los contrapunteos versificados de la

guajirada montuna y la curreria affo-cubana" (p. 11-12).

This content downloaded from

132.174.252.179 on Thu, 05 Nov 2020 20:35:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Waite - Lenin in Las MeninasDocument39 pagesWaite - Lenin in Las MeninasKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Craven The Visual Arts Since The Cuban RevolutionDocument27 pagesCraven The Visual Arts Since The Cuban RevolutionKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Krauss Late Capitalist Museum-12u8xdfDocument16 pagesKrauss Late Capitalist Museum-12u8xdfpazNo ratings yet

- Andermann Optic of The State, Ch. 5&6Document53 pagesAndermann Optic of The State, Ch. 5&6Karen BenezraNo ratings yet

- Fox, PAU Visual Arts SectionDocument25 pagesFox, PAU Visual Arts SectionKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Díaz-Duhalde, Interrupted Visions of HistoryDocument25 pagesDíaz-Duhalde, Interrupted Visions of HistoryKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Gilpin On Picturesque BeautyDocument182 pagesGilpin On Picturesque BeautyKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Viñas, David Foundation of The Liberal StateDocument9 pagesViñas, David Foundation of The Liberal StateKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Theorist of Subaltern Subjectivity: Antonio Gramsci, Popular Beliefs, Political Passion, and Reciprocal LearningDocument32 pagesTheorist of Subaltern Subjectivity: Antonio Gramsci, Popular Beliefs, Political Passion, and Reciprocal LearningBruno ReinhardtNo ratings yet

- Patnaik Gramsci Common SenseDocument9 pagesPatnaik Gramsci Common SenseKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Thomas - Refiguring The SubalternDocument24 pagesThomas - Refiguring The SubalternKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Croce, Philosophy and Intellectuals: Three Aspects of Gramsci's Theory of HegemonyDocument19 pagesCroce, Philosophy and Intellectuals: Three Aspects of Gramsci's Theory of HegemonyKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Kelley Notes On Deconstructing The FolkDocument11 pagesKelley Notes On Deconstructing The FolkKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Britton, "How To Be Primitive"Document15 pagesBritton, "How To Be Primitive"Karen BenezraNo ratings yet

- Jonsson Society Degree ZeroDocument32 pagesJonsson Society Degree ZeroKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Pluth - On Silence PDFDocument110 pagesPluth - On Silence PDFKaren Benezra100% (1)

- Shaw Trilce I RevisitedDocument6 pagesShaw Trilce I RevisitedKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Kam, Felipe Ehrenberg - A Neoligist's Art and ArchiveDocument30 pagesKam, Felipe Ehrenberg - A Neoligist's Art and ArchiveKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Forgacs National-Popular Genealogy of A ConceptDocument11 pagesForgacs National-Popular Genealogy of A ConceptKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Greenshields Writing The Structures of The Subject PDFDocument299 pagesGreenshields Writing The Structures of The Subject PDFKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Greenshields Writing The Structures of The Subject PDFDocument299 pagesGreenshields Writing The Structures of The Subject PDFKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Smith, Daniel What Is The Body Without Organs PDFDocument16 pagesSmith, Daniel What Is The Body Without Organs PDFKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Buchanan - Problem Body Deleuze Guattari PDFDocument19 pagesBuchanan - Problem Body Deleuze Guattari PDFKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Smith, Daniel What Is The Body Without Organs PDFDocument16 pagesSmith, Daniel What Is The Body Without Organs PDFKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Zupancic, Death Drive in Deleuze and LacanDocument18 pagesZupancic, Death Drive in Deleuze and LacanKaren Benezra100% (1)

- Pluth - On Silence PDFDocument110 pagesPluth - On Silence PDFKaren Benezra100% (1)

- Buchanan - Problem Body Deleuze Guattari PDFDocument19 pagesBuchanan - Problem Body Deleuze Guattari PDFKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Smtih Contemporary Art and Contemporaneity PDFDocument28 pagesSmtih Contemporary Art and Contemporaneity PDFKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- Legrás, Horacio Inheritances of Carlos ColombinoDocument17 pagesLegrás, Horacio Inheritances of Carlos ColombinoKaren BenezraNo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5794)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (73)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (344)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Harry PotterDocument17 pagesHarry PotterNina AntićNo ratings yet

- Ug 3 FC 2Document200 pagesUg 3 FC 2Sukhmander SinghNo ratings yet

- Percy Bysshe ShelleyDocument19 pagesPercy Bysshe ShelleySyeda MaryamNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1 Philippine Literary HISTORY FROM PRE-COLONIAL TO THE CONTEMPORARYDocument249 pagesLesson 1 Philippine Literary HISTORY FROM PRE-COLONIAL TO THE CONTEMPORARYrochell petilNo ratings yet

- Review ofDocument6 pagesReview ofalexa de veraNo ratings yet

- Ambrose HuiDocument2 pagesAmbrose HuiShuen Maggie ValtgisouNo ratings yet

- Wordsworth (Test) 04.06.2021Document22 pagesWordsworth (Test) 04.06.2021gopalNo ratings yet

- ContextDocument2 pagesContextMenon HariNo ratings yet

- The Help by Kathryn Stockett Teacher Resource 2018Document26 pagesThe Help by Kathryn Stockett Teacher Resource 2018Chura Alarcon Rocio SalomeNo ratings yet

- Ele 3101Document56 pagesEle 3101Mohd Adib Azfar MuriNo ratings yet

- The Unwanted Roommate - Webtoon Manhwa Hentai - Chapter 2 - ManhwaHentai - MeDocument1 pageThe Unwanted Roommate - Webtoon Manhwa Hentai - Chapter 2 - ManhwaHentai - Mejager33% (3)

- Elizabethan PeriodDocument15 pagesElizabethan PeriodJang MagbanuaNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Hamlet Criticism.Document125 pagesA Guide To Hamlet Criticism.João VitorNo ratings yet

- Harold Bloom - Robert Louis Stevenson (Bloom's Modern Critical Views) (2005)Document341 pagesHarold Bloom - Robert Louis Stevenson (Bloom's Modern Critical Views) (2005)danielahaisanNo ratings yet

- 1 Drama Online - Essential ShakespearretationDocument3 pages1 Drama Online - Essential ShakespearretationImranNo ratings yet

- Chapter 18 The EnemyDocument12 pagesChapter 18 The EnemyTRICKS BY YOGESHNo ratings yet

- Lesson 6 - Writing DramaDocument10 pagesLesson 6 - Writing DramaMargielane AcalNo ratings yet

- Rizal Week-3Document20 pagesRizal Week-3Junvy15100% (1)

- Dante InfernoDocument399 pagesDante InfernoThe LumberjackNo ratings yet

- (Topics in The Digital Humanities) Jockers, Matthew Lee - Macroanalysis - Digital Methods and Literary History-University of Illinois Press (2013)Document208 pages(Topics in The Digital Humanities) Jockers, Matthew Lee - Macroanalysis - Digital Methods and Literary History-University of Illinois Press (2013)AlessonRotaNo ratings yet

- A Creation Myth From The Yoruba People of West AfricaDocument5 pagesA Creation Myth From The Yoruba People of West AfricaweidforeverNo ratings yet

- Robert Greene (American Author)Document7 pagesRobert Greene (American Author)Luis La Torre JaramilloNo ratings yet

- Grief of Jose "Pepe"Document3 pagesGrief of Jose "Pepe"Reycel Jane YcoyNo ratings yet

- Afanasyev - First Emotion - RomanticDocument15 pagesAfanasyev - First Emotion - Romanticrorry.riaruNo ratings yet

- Collection of Literature 1Document20 pagesCollection of Literature 1mahnoor fatimaNo ratings yet

- Ma'at 42 Negative ConfessionsDocument16 pagesMa'at 42 Negative ConfessionsRahim441182% (11)

- How To Write A Great Master ThesisDocument7 pagesHow To Write A Great Master Thesistunwpmzcf100% (2)

- Death Note Manga - Google SearchDocument6 pagesDeath Note Manga - Google SearchanoushkaNo ratings yet

- UrduDocument3 pagesUrdukannadiparamba67% (3)

- 61354-Chapter 4Document15 pages61354-Chapter 4Somaia OmarNo ratings yet