Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Prevalence of Learning Disability

Uploaded by

jengki1Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Prevalence of Learning Disability

Uploaded by

jengki1Copyright:

Available Formats

SUPPLEMENT ARTICLE

Lifetime Prevalence of Learning Disability Among

US Children

Maja Altarac, MD, PhD, Ekta Saroha, MA

Department of Maternal and Child Health, School of Public Health, University of Alabama, Birmingham, Alabama

The authors have indicated they have no financial interests relevant to this article to disclose.

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE. Our goal was to examine the lifetime prevalence of learning disability by

sociodemographic and family-functioning characteristics in US children, with

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/

particular attention paid to the children with special health care needs. peds.2006-2089L

METHODS. By using data from the National Survey of Children’s Health, we calcu- doi:10.1542/peds.2006-2089L

lated lifetime prevalence of learning disability using a question that asked whether Key Words

learning disability, national estimates,

a doctor or other health care or school professional ever told the survey respon- prevalence, children with special health

dent that the child had a learning disability. Children with and those without care needs, family functioning

special health care needs were classified on the basis of how many of 5 definitional Abbreviations

criteria for children with special health care needs they met (0 –5). Bivariate and LD—learning disability

MCHB—Maternal and Child Health Bureau

multivariate statistical methods were used to assess independent associations of CSHCN— children with special health care

selected sociodemographic and family variables with learning disability. needs

SHCN—special health care need

RESULTS. The lifetime prevalence of learning disability in US children is 9.7%. NSCH—National Survey of Children’s

Health

Although prevalence of learning disability is lower among average developing FPL—federal poverty level

children (5.4%), it still affected 2.7 million children compared with 3.3 million DHHS—Department of Health and Human

Services

(27.8%) children with special health care needs. As the number of definitional OR— odds ratio

criteria children with special health care needs met increased from 1 to 5, so did CI— confidence interval

the prevalence of learning disability (15.0%, 27.1%, 41.6%, 69.3%, and 87.8%, NHIS—National Health Interview Survey

Accepted for publication Sep 15, 2006

respectively). In the adjusted logistic regression model, in addition to the number

Address correspondence to Maja Altarac, MD,

of definitional criteria the children met, variables associated with the increased odd PhD, MPH, Department of Maternal and Child

ratios of learning disability were lower education, all categories of poverty ⬍300% Health, School of Public Health, University of

Alabama, RPHB 320, 1530 Third Ave South,

of the federal poverty level, being male, increasing age, having a 2-parent step- Birmingham, AL 35294-0022. E-mail:

family or other family structure, being adopted, presence of a smoker, respon- maltarac@uab.edu

dent’s higher responses on aggravation in parenting scale, sharing ideas with the PEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005;

Online, 1098-4275); published in the public

child less than very well, and never, rarely, or sometimes discussing serious domain by the American Academy of

disagreements calmly. Pediatrics

CONCLUSIONS. Although more than half of lifetime prevalence of learning disability

occurred in children with special health care needs, it is a significant morbidity in

average-developing children as well. Learning disabilities represent important

comorbidities among children with special health care needs.

PEDIATRICS Volume 119, Supplement 1, February 2007 S77

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on February 14, 2021

L EARNING DISABILITY (LD) is a term used to describe a

constellation of disorders manifested by significant

difficulties in listening, speaking, reading (either reading

our CSHCN variables. These screening questions were

developed by using the MCHB definition of CSHCN as

the underlying conceptual framework.5,11 Screening

skill or reading comprehension), writing, reasoning, questions can be grouped on 5 definitional criteria for

mathematics (either in mathematical calculation or CSHCN: prescription medication use, above-average ser-

mathematical reasoning), foreign languages, coordina- vices use, functional limitations, use of mental health

tion, spatial adaptation, memorization, and social stud- services, and use or need for specialized therapies. We

ies.1–3 These difficulties can occur alone or in varying constructed 5 variables, 1 for each criterion, if a child

combinations and can range from mild to severe diffi- met the criterion because of any medical, behavioral, or

culties.4 Although LD cannot be cured, the underlying other health condition lasting or expected to last at least

conditions can be treated and managed so that children 12 months. Furthermore, because many CSHCN chil-

with LD adapt, achieve academic success, and live pro- dren meet ⬎1 definitional criterion, we created a vari-

ductive, fulfilling lives.4 able that counts how many of 5 possible criteria a child

The Maternal and Child Health Bureau (MCHB) de- met. We also computed a global dichotomous (yes/no)

fines children with special health care needs (CSHCN) as CSHCN variable on the basis of whether a child met at

those who have or are at increased risk for a chronic least 1 of the 5 criteria.

physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional con- Sociodemographic variables included were child’s

dition and who also require health and related services gender, highest education attained by anyone in the

of a type or amount beyond that required by children household (less than high school, high school, more

generally.5 In light of this definition, all children with LD than high school), poverty expressed as percentage of

could be classified as CSHCN. However, given the com- federal poverty level (FPL) based on Department of

plexity of difficulties involved in LD and measurement Health and Human Services (DHHS) guidelines (FPL:

issues involved in screening for CSHCN, it is possible that $18 400 for a family of 4 in 2003), employment (yes/no)

many children with LD are not identified as CSHCN. was coded “yes” if anyone in the household was em-

Family functioning is a critical component of chil- ployed at least 50 of the past 52 weeks, primary language

dren’s well-being and development. Although only a spoken (English or Spanish), Latino ethnicity (yes/no),

handful of studies examined it, several studies noted race (white, black, mixed, or other). Family structure

poorer family functioning in families with children with was categorized into 4 groups: 2-parent (other than step)

LD.6–8 Our aim was to address paucity of epidemiologic family, 2-parent stepfamily, single mother (no father

studies of LD and associated sociodemographic and fam- present), and other. Children were considered adopted if

ily characteristics. they lived in a household with an adoptive but no bio-

The objective of this study was to produce estimates logical parent. Presence of a smoker in the household

of LD from a large-scale, nationally representative sur- was coded as “yes” if anyone in the household used

vey and be first to examine the association between cigarettes, cigars, or pipe tobacco.

lifetime prevalence of LD by sociodemographic and fam- Relationship with the child was measured with a

ily-functioning characteristics in US children ⬍18 years question that asked, “Is your relationship with child very

old in 2003, with particular attention paid to the child’s close, somewhat close, not very close or not close at all?”

special health care need (SHCN) status. Sharing ideas with the child was measured with a ques-

tion that asked, “How well can you and [child] share

METHODS ideas or talk about things that really matter?”, with

answer options very well, somewhat well, not very well,

Data Source and not very well at all. Ate meals together in the past

Data for this study were derived from the 2003 National week was measured with a question that asked “During

Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH). More details about the past week on how many days did all family members

the survey are provided by Kogan and Newacheck9 in who live in the household eat a meal together?” An-

this issue; more in-depth information can be found else- swers were categorized into 3 groups: every day (7 days),

where.10 All children were included in this study. frequently (3– 6 days), and never and rarely (0 –2 days).

Aggravation in parenting was measured with the Ag-

Study Variables gravation in Parenting Scale, which was derived from

Lifetime prevalence of LDs was measured by a question the Parental Stress Index12 and the Parental Attitudes

that asked: “Has a doctor, health professional, teacher or about Childrearing scale.10,13 It consists of 4 questions

school official ever told you [child] has a learning dis- that asked respondents how often during the past month

ability?” Answers were available for children aged 3 to they felt child was harder to care for than most children

17. their age, they felt child did things that really bothered

The CSHCN Screener11 was incorporated in the them a lot, they felt they were giving up more of their

NSCH.10 We used those screening questions to compute life to meet child’s needs, and they felt angry with child,

S78 ALTARAC, SAROHA

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on February 14, 2021

with answers recorded on 4-point Likert scale (never, 8.9% in children age 8, to 10.3% in children age 9 and

sometimes, usually, and always) and had standardized leveling off at the 12% to 14% range in children age 10

item ␣ ⫽ .63. A scale average was computed where to 17 years. Demographic characteristics are presented in

higher scores indicated higher aggravation. Several Table 1, in the first column as a percentage of the total

questions were available on ways families deal with study sample, and next as a percentage of children with

serious disagreements, with answers recorded on a LD. Lifetime prevalence of LD was significantly higher in

5-point Likert scale (never to always). The questions had boys, those speaking English as a primary language,

the same stem “When you have a serious disagreement living in a household with lower education, living in

with your household members, how often do you” and poverty, and living in a household where nobody was

asked about following: just keep your opinions to your- employed at least 50 of the past 52 weeks. Prevalence of

self; argue heatedly or shout; or end up hitting or throw- LD was about the same among white, black, and mixed

ing things. These 3 variables were dichotomized so that race children but was significantly lower among children

the sometimes, usually, and always group was compared of other races. Latino ethnicity was not related to LD.

with the never and rarely group. Discussing serious dis-

agreements calmly variable, based on the question Lifetime Prevalence of LD by SHCN Status

“When you have a serious disagreement with your CSHCN represented 17.6% (95% CI: 17.2–18.0) of US

household members, how often do you discuss your children in 2003. Lifetime prevalence of LD in CSHCN

disagreements calmly?” was dichotomized so that the was 27.8% (95% CI: 26.6 –29.0) compared with 5.4%

never, rarely, and sometimes group was compared with (95% CI: 5.1–5.7) in non-CSHCN. However, the preva-

the usually and always group. The above categorizations lence varied by the type of definitional criteria for

were performed because the prevalence of LD was sim- CSHCN a child met, with the lowest prevalence in

ilar among these answers. CSHCN with prescription medication use (23.9%; 95%

CI: 22.7–25.2), followed by CSHCN with above-average

Data Analysis services use (43.4%; 95% CI: 41.4 – 45.4), functional

Bivariate analyses were used to compare demographic limitations (49.8%; 95% CI: 46.8 –52.7), use of mental

and family characteristics of children with and without health services (51.7%; 95%: CI 49.2–54.2), and use or

LD. Logistic regression was used to calculate crude and need for specialized therapies (63.8%; 95% CI: 60.6 –

adjusted odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals 66.9). These categories are not mutually exclusive; quite

(CIs) for LD. Differences were considered significant at the contrary, nearly half of CSHCN (45.6%) met ⱖ2

the .05 level (2-tailed test). All variables significantly definitional criteria. The prevalence of LD increased dra-

associated with LD at the bivariate level were entered matically as the number of criteria met increased, from

into multivariate logistic regression, and those not sig- 15.0% in CSHCN who met only 1 criterion to 86.8% in

nificant were removed to obtain the most parsimonious CSHCN who met all 5 criteria (Fig 1).

model. Data analyses were done by SAS-callable

SUDAAN, which allowed us to account for the complex Lifetime Prevalence of LD by Family Characteristics

survey design and calculate accurate variance statistics.14 Family characteristics are also presented in Table 1. Chil-

Survey weights provided by the data-collection agency dren from 2-parent families (other than stepfamilies)

were used to produce valid national population esti- had lower lifetime prevalence of LD (7.5%) than chil-

mates.10 dren with different family structures (11.8%–14.0%).

Significantly more adopted children had LD than non-

Human Subjects adopted children (20.4% vs 9.3%, respectively). Life-

Because data used in analyses are publicly available and time prevalence of LD was statistically significantly

contain no personal identifying information, this study higher if there was a smoker in a household, if the

qualified for and received exempt review from the insti- relationship with a child was not very close, if they did

tutional review board at the University of Alabama at not share ideas very well, if they ate meals together

Birmingham. rarely or never in the past week, if they seldom discussed

serious disagreements calmly, and if in dealing with

serious disagreements they argued heatedly or shouted

RESULTS

and ended up hitting or throwing things sometimes to

Lifetime Prevalence of LD always. Mean aggravation in parenting score was 1.64

Overall lifetime prevalence of LD in US children in 2003 (95%: CI 1.64 –1.65) in the total sample, and among

was 9.7% (95% CI: 9.4 –10.1), meaning that an esti- children with lifetime LD it was statistically significantly

mated 6 million US children age ⬍18 years ever had LD. higher than in those without (1.88, 95% CI: 1.85–1.90

Lifetime prevalence of LD increased with age from just vs 1.62, 95% CI: 1.61–1.63), indicating that families of

⬎2% in children age 3 and 4, to 3.8% in children age 5, children with LD experience higher aggravation in par-

to 5.9% in children age 6, to 8.4% in children age 7, to enting.

PEDIATRICS Volume 119, Supplement 1, February 2007 S79

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on February 14, 2021

TABLE 1 Sociodemographic and Family Characteristics of US Children Aged <18 Years in 2003, According to Lifetime LD Prevalence

Variables Total With LD SE 2 df P

% 95% CI SE % 95% CI

Gender

Male 51.1 50.6–51.7 0.28 12.2 11.7–12.8 0.28

Female 48.9 48.3–49.4 0.28 7.1 6.7–7.6 0.23 202.6 1 ⬍.001

Primary language

English 87.3 86.9–87.7 0.22 10.0 9.6–10.4 0.19

Spanish 12.7 12.3–13.2 0.22 8.0 6.9–9.2 0.58 10.7 1 .001

Ethnicity

Latino 17.5 17.1–18.0 0.23 9.7 9.4–10.1 0.53

Not Latino 82.5 82.0–82.9 0.23 9.8 8.9–10.9 0.19 0.05 1 NS

Race

White 74.7 74.1–75.2 0.28 9.8 9.4–10.2 0.20

Black 16.5 16.0–16.9 0.23 11.1 10.0–12.3 0.58

Multiple race 3.7 3.5–3.9 0.10 10.8 9.0–12.9 1.00

Other race 5.2 4.9–5.6 0.18 5.8 4.7–7.2 0.63 38.9 3 ⬍.001

Highest education in the household

Less than high school 7.9 7.5–8.2 0.19 13.4 11.7–15.2 0.90

High school 26.5 26.0–27.0 0.26 12.3 11.5–13.2 0.41

More than high school 65.7 65.2–66.2 0.28 8.3 7.9–8.7 0.19 100.9 2 ⬍.001

Povertya

⬍100% 17.9 17.4–18.4 0.26 14.8 13.6–16.1 0.65

100% to ⬍133% 7.9 7.5–8.2 0.17 12.5 11.0–14.2 0.80

133% to ⬍150% 4.0 3.8–4.3 0.13 10.3 8.5–12.5 1.03

150% to ⬍185% 7.3 7.0–7.7 0.16 10.3 9.0–11.9 0.72

185% to ⬍200% 3.7 3.5–3.9 0.10 11.1 9.3–13.3 1.02

200% to ⬍300% 17.5 17.1–17.9 0.21 9.5 8.7–10.4 0.42

300% to ⬍400% 15.1 14.7–15.5 0.20 7.5 6.8–8.2 0.37

ⱖ400% 26.7 26.2–27.1 0.24 6.9 6.4–7.4 0.27 182.2 7 ⬍.001

Anyone in the household employed

at least 50 of the past 52 wk

Yes 89.8 89.5–90.2 0.19 9.1 8.7–9.5 0.18

No 10.2 9.8–10.6 0.19 15.5 14.1–17.0 0.74 69.6 1 ⬍.001

Family structure

2 parents, other than stepfamily 63.5 63.0–64.1 0.28 7.5 7.2–7.9 0.20

2 parents, stepfamily 8.6 8.3–8.9 0.16 14.0 12.6–15.4 0.70

Single mother, no father present 23.4 23.0–23.9 0.25 12.4 11.6–13.3 0.44

Other 4.5 4.2–4.7 0.12 11.8 10.3–13.5 0.82 175.6 3 ⬍.001

Adopted

Yes 1.7 1.6–1.9 0.06 20.4 17.5–23.5 1.53

No 98.3 98.1–98.4 0.06 9.3 9.0–9.7 0.18 48.7 1 ⬍.001

Smoker in the household

Yes 29.5 29.0–30.0 0.26 13.5 12.7–14.2 0.38

No 70.5 70.0–71.0 0.26 8.9 8.5–9.4 0.22 107.9 1 ⬍.001

Relationship with the child

Very close 85.7 85.1–86.1 0.24 10.9 10.5–11.4 0.23

Somewhat close 13.4 13.0–13.9 0.23 14.9 13.6–16.3 0.69

Not very close 0.7 0.6–0.9 0.07 17.1 11.7–24.2 3.17

Not at all close 0.2 0.1–0.3 0.03 13.3 7.2–23.3 4.01 33.5 3 ⬍.001

Sharing ideas

Very well 75.2 74.7–75.8 0.29 9.9 9.4–10.3 0.23

Somewhat well 22.9 22.3–23.5 0.29 15.2 14.2–16.2 0.51

Not very well 1.5 1.3–1.7 0.09 30.2 24.5–36.6 3.11

Not at all well 0.4 0.3–0.4 0.04 43.0 34.1–52.4 4.73 157.3 3 ⬍.001

Ate meals together in the past week

Rarely or never (0–2 d) 15.2 14.8–15.6 0.20 10.8 10.0–11.8 0.46

Frequently (3–6 d) 37.5 37.0–38.1 0.26 9.4 8.9–10.0 0.27

Every day (7 d) 47.2 46.7–47.8 0.28 9.6 9.1–10.2 0.28 7.3 2 ⬍.05

When you have a serious disagreement, how often do you:

Discuss your disagreements calmly

Never, rarely, or sometimes 29.3 28.8–29.8 0.27 11.9 11.2–12.7 0.38

Usually or always 70.7 70.2–71.2 0.27 8.8 8.4–9.2 0.20 53.3 1 ⬍.001

S80 ALTARAC, SAROHA

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on February 14, 2021

TABLE 1 Continued

Variables Total With LD SE 2 df P

% 95% CI SE % 95% CI

Keep your opinion to yourself

Sometimes, usually, or always 42.9 42.3–43.5 0.28 10.1 9.6–10.7 0.28

Never or rarely 57.1 56.5–57.6 0.28 9.4 9.0–9.9 0.24 3.8 1 .05

Argue heatedly or shout

Sometimes, usually, or always 38.7 38.2–39.3 0.28 11.2 10.6–11.8 0.30

Never or rarely 61.3 60.7–61.8 0.28 8.7 8.3–9.2 0.22 41.9 1 ⬍.001

End up hitting or throwing things

Sometimes, usually, or always 2.9 2.7–3.1 0.11 14.0 11.5–17.0 1.41

Never or rarely 97.1 96.9–97.3 0.11 9.6 9.2–10.0 0.18 9.7 1 .002

NS indicates not significant.

a Percent FPL is based on DHHS guidelines.

Lifetime Prevalence of LD: Adjusted Multivariate Results where a similar question was used to measure LD.15

The results of multivariate logistic regression confirmed Although more than half of lifetime prevalence of LD

that number of CSHCN definitional criteria had the occurred in CSHCN, it is a significant morbidity in aver-

strongest association with LD. Both unadjusted and ad- age-developing children as well, affecting ⬃1 in 20,

justed ORs and 95% CIs are presented in Table 2. In the which translates into nearly 3 million US children.

adjusted logistic regression model, sociodemographic Among CSHCN, the prevalence of LD increased as the

variables associated with the increased odds of lifetime number of definitional criteria for CSHCN a child met

prevalence of LD were increasing age, male gender, increased, from 15.0% for 1 criterion to 86.8% for chil-

lower household education, and all categories of poverty dren who met all 5 criteria. This indicates that LD is an

⬍300% of FPL. Family variables associated with in- important comorbidity among CSHCN, especially those

creased odds of lifetime prevalence of LD in the adjusted with multiple needs or using multiple kinds of services.

model were having a 2-parent stepfamily or other family It has been noted that children with LD have other

structure, being adopted, presence of a smoker in the difficulties or mental health disorders.4,16 Analysis of

home, sharing ideas with the child less than very well, NHIS data indicated that a greater percentage of children

survey respondent’s higher responses on aggravation in with LD had cognitive, sensory, and other chronic con-

parenting scale, and never, rarely, or sometimes discuss- dition compared with children without LD or attention-

ing serious disagreements calmly. deficit disorder.17 However, our study is the first, to our

knowledge, to examine and report on a dramatic in-

DISCUSSION crease in prevalence of LD in CSHCN with multiple

Our results indicate that LD is a common chronic con- needs or using multiple kinds of services.

dition among US children, affecting ⬃1 in 10 overall. In our study we have shown the prevalence of LD

This is slightly higher than estimate of 8% reported using rises with child’s increasing age, reaching stable levels

2003 National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) data, during adolescence. Most children get an LD diagnosis

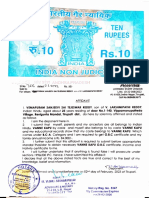

FIGURE 1

Lifetime prevalence of LD in US children aged ⬍18

years in 2003 according to the number of definitional

criteria for SHCN that a child met.

PEDIATRICS Volume 119, Supplement 1, February 2007 S81

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on February 14, 2021

TABLE 2 Multiple Logistic Regression Results for Lifetime Prevalence of LD and Sociodemographic and Family-Functioning Variables

Variables Unadjusted Adjusteda

OR 95% CI OR 95% CI

No. of definitional criteria for SHCN a child met (of 5)

0 1.00 1.00

1 3.10 2.75–3.49 2.97 2.60–3.40

2 6.54 5.68–7.53 5.64 4.78–6.65

3 12.49 10.68–14.59 9.53 7.86–11.54

4 39.63 31.98–49.11 24.57 18.81–32.10

5 115.45 78.32–170.17 75.00 46.02–122.24

Age 1.11 1.10–1.12 1.08 1.06–1.09

Gender

Male 1.82 1.67–1.98 1.67 1.51–1.85

Female 1.00 1.00

Highest education in the household

Less than high school 1.71 1.45–2.01 1.42 1.13–1.80

High school 1.56 1.42–1.70 1.37 1.21–1.55

More than high school 1.00 1.00

Povertyb

⬍100% 2.34 2.06–2.67 1.88 1.55–2.29

100% to ⬍133% 1.93 1.63–2.27 1.52 1.21–1.90

133% to ⬍150% 1.56 1.23–1.96 1.42 1.07–1.89

150% to ⬍185% 1.56 1.31–1.85 1.29 1.02–1.62

185% to ⬍200% 1.69 1.36–2.10 1.37 1.05–1.78

200% to ⬍300% 1.42 1.25–1.61 1.34 1.16–1.54

300% to ⬍400% 1.09 0.95–1.24 1.06 0.91–1.24

ⱖ400% 1.00 1.00

Family structure

2 parents, other than stepfamily 1.00 1.00

2 parents, stepfamily 1.99 1.75–2.26 1.32 1.12–1.56

Single mother, no father present 1.74 1.58–1.92 1.03 0.90–1.17

Other 1.64 1.40–1.94 1.29 1.04–1.61

Adopted

Yes 2.49 2.06–3.01 1.54 1.17–2.03

No 1.00 1.00

Anyone in the household smoking

Yes 1.59 1.46–1.73 1.16 1.04–1.30

No 1.00

Sharing ideas

Very well 1.00 1.00

Somewhat well 1.63 1.49–1.79 1.18 1.05–1.33

Not very well 3.95 2.95–5.30 1.42 0.92–2.19

Not at all well 6.90 4.71–10.11 1.38 0.89–2.15

Aggravation in parenting 2.58 2.39–2.78 1.32 1.18–1.47

Discuss serious disagreements calmly

Never, rarely, or sometimes 1.41 1.29–1.54 1.16 1.03–1.29

Usually and always 1.00 1.00

a The adjusted model contained all variables presented.

b Percent FPL is based on DHHS guidelines.

during early to mid adolescence; however, LD does not Consistent with other reports, in our adjusted analy-

develop during adolescence; they have had it all along. ses we found LD to be associated with male gender15,19,20

Several authors comment on hidden, invisible, and and poverty.15,20 We also found that lower household

seemingly benign nature of an LD, even calling it its education was associated with higher odds of LD. NHIS

most socially significant feature.4,7,18 LDs are difficult to data indicated increased association of LD with lower

diagnose, and as a group of disorders are poorly under- maternal education.20 Even after adjusting for CSHCN

stood.16,18 It was shown that on average there is a 3.5- status, age, gender, household education, and poverty,

year gap between the child’s age at LD diagnosis and several family variables were related to increased prev-

mother’s first suspicion of a problem.18 The treatment of alence of LD, underlying the importance of family fac-

LD focuses on educational interventions, and early in- tors. In our study, the odds of LD in single-mother, no

terventions are most desirable.4,16 Therefore, it is impor- father-present family was no different from 2-parent

tant to identify LD as soon as possible. family (other than stepfamily); this differs from the NHIS

S82 ALTARAC, SAROHA

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on February 14, 2021

result where more LD was observed in single-mother 2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Man-

families.17 However, we reported higher prevalence of ual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American

Psychiatric Association; 1994

LD among children living in 2-parent stepfamilies and

3. Hammill DD. On defining learning disabilities: an emerging

other family structures (other than 2-parent or single-

consensus. J Learn Disabil. 1990;23:74 – 84

mother family). It is of a particular note that ⬃1 in 5 4. Shapiro BK, Gallico RP. Learning disabilities. Pediatr Clin North

adopted children have a LD, a significantly higher num- Am. 1993;40:491–505

ber than in children who are not adopted, and this 5. McPherson M, Arango P, Fox H, et al. A new definition of

relationship persists in the adjusted logistic regression children with special health care needs. Pediatrics. 1998;102:

model. This is the first study, to our knowledge, to report 137–140

6. Michaels CR, Lewandowski LJ. Psychological adjustment and

on prevalence and ORs of LD among adopted children.

family functioning of boys with learning disabilities. J Learn

Furthermore, survey respondents from families with an

Disabil. 1990;23:446 – 450

LD child were more likely to report that they could not 7. Dyson LL. The experiences of families of children with learning

share ideas or talk about things that really matter with disabilities: parental stress, family functioning, and sibling self-

an LD child very well. Moreover, they were more likely concept. J Learn Disabil. 1996;29:280 –286

to report higher aggravation in parenting and that they 8. Tollison P, Palmer DJ, Stowe ML. Mothers’ expectations,

seldom discuss serious disagreements with household interactions, and achievement attributions for their learning

disabled or normally achieving sons. J Spec Educ. 1987;21:

members calmly, indicating higher familial strain.

83–93

9. Kogan MD, Newacheck PW. Introduction to the volume on

CONCLUSIONS

articles from the National Survey of Children’s Health. Pediat-

This study uses a nationally representative sample of US rics. 2007;119(suppl 1):S1–S3

children, so our results are generalizable to the uninsti- 10. Blumberg SJ, Olson L, Frankel M, Osborn L, Srinath KP, Gi-

tutionalized civilian US children. Our main limitation ambo P. Design and operation of the National Survey of Chil-

lies in the measurement of our dependent variable, LD. dren’s Health, 2003. Vital Health Stat 1. 2005;(43):1–124

We only have a rather crude measure of lifetime LD, 11. Bethell CD, Read D, Stein RE, Blumberg SJ, Wells N, Newa-

check PW. Identifying children with special health care needs:

based on answers to the question if a doctor, health

development and evaluation of a short screening instrument.

professional, teacher, or school official ever told the

Ambul Pediatr. 2002;2:38 – 48

survey respondent that the child had a LD. We do not 12. Abidin RR. A measure of the parent-child system. In: Zalaquett

have any details about it, such as what specific diagnosis CP, Woods RJ, eds. Evaluating Stress: A Book of Resources. Lan-

was made, how severe this disability is, what kind of ham, MD: Scarecrow Press, Inc; 1997:277–291

LD-related services or special education a child is receiv- 13. Easterbrooks MA, Goldberg WA. Toddler development in the

ing, etc. Some of this information might be collected in family: impact of father involvement and parenting character-

istics. Child Dev. 1984;55:740 –752

2007 NSCH and will allow us to perform more detailed

14. Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN Language Manual, Release

analyses and deepen understanding of LD among US

9.0. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute;

children. Yet, despite this limitation, our results repre- 2004

sent a conservative estimate of the true prevalence of LD 15. Dey AN, Bloom B. Summary health statistics for US children:

among US children because it is based on survey respon- National Health Interview Survey, 2003. Vital Health Stat 10.

dent’s report of LD by an objective third party, an expert, 2005;(223):1–78

a health or educational professional, and knowing that 16. First M, Tasman A. DSM-IV-TR Mental Disorders Diagnosis, Etiol-

ogy and Treatment. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 2004

there is a significant time lag before diagnosis.

17. Pastor PN, Reuben CA. Attention deficit disorder and learning

disability: United States, 1997–98. Vital Health Stat 10. 2002;

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

(206):1–12

We thank Matthew D. Bramlett, PhD, of the National 18. Faerstein LM. Stress and coping in families of learning disabled

Center for Health Statistics for making inclusion of adop- children: a literature review. J Learn Disabil. 1981;14:420 – 423

tion variable results possible. 19. Rutter M, Caspi A, Fergusson D, et al. Sex differences in

developmental reading disability: new findings from four epi-

REFERENCES demiological studies. JAMA. 2004;291:2007–2012

1. Office of Education. Assistance to states for education of hand- 20. Zill N, Schoenborn CA. Developmental, learning, and emo-

icapped children: procedures for evaluating specific learning tional problems: health of our nation’s children, United States,

disability. Fed Regist. 1977;42:65– 83 1988. Adv Data. 1990;(190):1–18

PEDIATRICS Volume 119, Supplement 1, February 2007 S83

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on February 14, 2021

Lifetime Prevalence of Learning Disability Among US Children

Maja Altarac and Ekta Saroha

Pediatrics 2007;119;S77

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089L

Updated Information & including high resolution figures, can be found at:

Services http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/Supplement_1/S77

References This article cites 16 articles, 2 of which you can access for free at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/Supplement_1/S77#

BIBL

Subspecialty Collections This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

following collection(s):

Developmental/Behavioral Pediatrics

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/development:behavior

al_issues_sub

Cognition/Language/Learning Disorders

http://www.aappublications.org/cgi/collection/cognition:language:lea

rning_disorders_sub

Permissions & Licensing Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures, tables) or

in its entirety can be found online at:

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/Permissions.xhtml

Reprints Information about ordering reprints can be found online:

http://www.aappublications.org/site/misc/reprints.xhtml

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on February 14, 2021

Lifetime Prevalence of Learning Disability Among US Children

Maja Altarac and Ekta Saroha

Pediatrics 2007;119;S77

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2006-2089L

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

located on the World Wide Web at:

http://pediatrics.aappublications.org/content/119/Supplement_1/S77

Pediatrics is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthly publication, it

has been published continuously since 1948. Pediatrics is owned, published, and trademarked by

the American Academy of Pediatrics, 345 Park Avenue, Itasca, Illinois, 60143. Copyright © 2007

by the American Academy of Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 1073-0397.

Downloaded from www.aappublications.org/news at Indonesia:AAP Sponsored on February 14, 2021

You might also like

- The Health and Well-Being of Adopted ChildrenDocument9 pagesThe Health and Well-Being of Adopted ChildrenAbdi ChimdoNo ratings yet

- Sleepless in America Inadequate Sleep and RelationDocument12 pagesSleepless in America Inadequate Sleep and RelationmagdalenaNo ratings yet

- PR 198458Document5 pagesPR 198458Louie Joice MartinezNo ratings yet

- Four Year Prospective Study of BMI and Mental Health Problems in Young Children SawyerDocument10 pagesFour Year Prospective Study of BMI and Mental Health Problems in Young Children SawyerdidiNo ratings yet

- A National Profile of Childhood Epilepsy and Seizure DisorderDocument11 pagesA National Profile of Childhood Epilepsy and Seizure DisorderYovan FabianNo ratings yet

- Maltreatment of Children With DisabilitiesDocument13 pagesMaltreatment of Children With DisabilitiesCatarina GrandeNo ratings yet

- Doc. ConricytDocument9 pagesDoc. ConricytAsiel EstradaNo ratings yet

- 2686-Article Text-15115-1-10-20210113Document6 pages2686-Article Text-15115-1-10-20210113Louie Joice MartinezNo ratings yet

- Peds 2009-2789 FullDocument12 pagesPeds 2009-2789 FullAunNo ratings yet

- Pone 0233949Document13 pagesPone 0233949Shanya rahma AdrianiNo ratings yet

- ChildrenDocument13 pagesChildrenAngie Lorena ParadaNo ratings yet

- Learning Disabilities and School Failure - Ped Rev Aug 2011Document12 pagesLearning Disabilities and School Failure - Ped Rev Aug 2011diaspalma.medNo ratings yet

- Sibling Ill Health and Children's Educational OutcomesDocument8 pagesSibling Ill Health and Children's Educational OutcomesTina JalilNo ratings yet

- Lectura Control 2 - Asignatura 3Document12 pagesLectura Control 2 - Asignatura 3CamilaGarridoNo ratings yet

- TangDocument16 pagesTangEvelynNo ratings yet

- NabeelaDocument4 pagesNabeelalada emmanuelNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status of School Age Children in Private Elementary Schools: Basis For A Proposed Meal Management PlanDocument5 pagesNutritional Status of School Age Children in Private Elementary Schools: Basis For A Proposed Meal Management PlanIjaems JournalNo ratings yet

- Maternal Profiles and Social Determinants of Malnutrition and The MDGS: What Have We Learnt?Document12 pagesMaternal Profiles and Social Determinants of Malnutrition and The MDGS: What Have We Learnt?FaniaParra FaniaNo ratings yet

- Modulo 03 CONTROL DE LECTURADocument10 pagesModulo 03 CONTROL DE LECTURAGloria Morales BastiasNo ratings yet

- Page 2021Document20 pagesPage 2021maria cristina aravenaNo ratings yet

- Wong 2014Document10 pagesWong 2014eka wahyuni wahyuniNo ratings yet

- Articol AutismDocument16 pagesArticol AutismOanaFloreaNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status and Associated Factors in Under-Five Children of RawalpindiDocument5 pagesNutritional Status and Associated Factors in Under-Five Children of RawalpindiMarya Fitri02No ratings yet

- Hubungan Menyusui Terhadap Perkembangan Motorik Dan Kemampuan BahasaDocument10 pagesHubungan Menyusui Terhadap Perkembangan Motorik Dan Kemampuan BahasaYossy RosmalasariNo ratings yet

- The Contribution of Family Functions, Knowledge and Attitudes in Children Under Five With StuntingDocument5 pagesThe Contribution of Family Functions, Knowledge and Attitudes in Children Under Five With Stuntingsarrah salsabilaNo ratings yet

- Ajol File Journals 205 Articles 227090 Submission Proof 227090 2437Document21 pagesAjol File Journals 205 Articles 227090 Submission Proof 227090 2437MuseNo ratings yet

- Estimating The Prevalence ofDocument8 pagesEstimating The Prevalence ofKarel GuevaraNo ratings yet

- Preferences and Growth How Do Toddler EaDocument9 pagesPreferences and Growth How Do Toddler EaFonoaudiólogaRancaguaNo ratings yet

- Ford 2003Document9 pagesFord 2003Arif Erdem KöroğluNo ratings yet

- GlobalDocument9 pagesGlobalmonster_2203No ratings yet

- PIIS2667193X23001394Document11 pagesPIIS2667193X23001394HitmanNo ratings yet

- The Effectiveness of Community-Based Nutrition Education On The Nutrition Status of Under-Five Children in Developing Countries. A Systematic ReviewDocument4 pagesThe Effectiveness of Community-Based Nutrition Education On The Nutrition Status of Under-Five Children in Developing Countries. A Systematic ReviewDesy rianitaNo ratings yet

- Clarity Article.Document12 pagesClarity Article.Shubha DiwakarNo ratings yet

- English For Academic Group 7 StuntingDocument10 pagesEnglish For Academic Group 7 StuntingNorma WijayaNo ratings yet

- School Feeding Programs in Developing Countries: Impacts On Children's Health and Educational OutcomesDocument17 pagesSchool Feeding Programs in Developing Countries: Impacts On Children's Health and Educational Outcomesobsa abdallaNo ratings yet

- Sha'ari N, 2017Document8 pagesSha'ari N, 2017Anibal LeNo ratings yet

- Impact of SDOH On Adolescents With ADHDDocument15 pagesImpact of SDOH On Adolescents With ADHDGrecia Medina SánchezNo ratings yet

- JPaediatrNursSci 6 2 80 81Document2 pagesJPaediatrNursSci 6 2 80 81Angelo FanusanNo ratings yet

- Preventing Chronic Disease: Prevalence of and Risk Factors For Adolescent Obesity in Southern Appalachia, 2012Document6 pagesPreventing Chronic Disease: Prevalence of and Risk Factors For Adolescent Obesity in Southern Appalachia, 2012Makmur SejatiNo ratings yet

- Material Hardship and The Physical Health of School-Aged Children in Low-Income HouseholdsDocument10 pagesMaterial Hardship and The Physical Health of School-Aged Children in Low-Income HouseholdsStephen CampbellNo ratings yet

- Poa05074 33 41Document9 pagesPoa05074 33 41Nikka Caram DomingoNo ratings yet

- European Journal of Pediatrics SciDocument7 pagesEuropean Journal of Pediatrics ScianimeshNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Feeding DisorderDocument6 pagesPediatric Feeding DisorderNadia Desanti RachmatikaNo ratings yet

- Remaja 1Document10 pagesRemaja 1rhamozaNo ratings yet

- Jurnal Ika 1Document11 pagesJurnal Ika 1jihadahNo ratings yet

- The Children's Eating Behavior InventoryDocument14 pagesThe Children's Eating Behavior Inventoryguilherme augusto paroNo ratings yet

- EhscarlapetersonDocument14 pagesEhscarlapetersonapi-533702960No ratings yet

- Ajcn 121061Document9 pagesAjcn 121061MARION JOCELIN MENANo ratings yet

- Holly A HarrisDocument7 pagesHolly A HarrisRemy MohammedNo ratings yet

- Autism Spectrum DisorderDocument1 pageAutism Spectrum Disordersarmiyati zainuddinNo ratings yet

- Family House HoldDocument17 pagesFamily House Holdnadiah khairunnisaNo ratings yet

- Childhood Obesity and Schools Evidence From The National Survey of Childrens HealthDocument9 pagesChildhood Obesity and Schools Evidence From The National Survey of Childrens HealthAbdul-Rahman SalemNo ratings yet

- Poverty in The US (AAP)Document19 pagesPoverty in The US (AAP)Bold MarvNo ratings yet

- J. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014 Gowey 552 61Document10 pagesJ. Pediatr. Psychol. 2014 Gowey 552 61Flavia DenisaNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status of Infants and Some Related Risk Factors in Shahroud, IranDocument6 pagesNutritional Status of Infants and Some Related Risk Factors in Shahroud, IranGiovanni MartinNo ratings yet

- Nutritional Status and Associated Factors in Under-Five Children of RawalpindiDocument6 pagesNutritional Status and Associated Factors in Under-Five Children of Rawalpindizahfira edwardNo ratings yet

- Prevalence of Malnutrition Among Under-Five Children in Al-Nohoud Province Western Kordufan, SudanDocument6 pagesPrevalence of Malnutrition Among Under-Five Children in Al-Nohoud Province Western Kordufan, SudanIJPHSNo ratings yet

- Taras Nutrition PaperDocument16 pagesTaras Nutrition PaperZaglord ZakNo ratings yet

- Determinants of Stunted Children in Indonesia: A Multilevel Analysis at The Individual, Household, and Community LevelsDocument6 pagesDeterminants of Stunted Children in Indonesia: A Multilevel Analysis at The Individual, Household, and Community LevelsRafika PutriNo ratings yet

- Caring for Children with Special Healthcare Needs and Their Families: A Handbook for Healthcare ProfessionalsFrom EverandCaring for Children with Special Healthcare Needs and Their Families: A Handbook for Healthcare ProfessionalsLinda L. EddyNo ratings yet

- VITAMIN A, INFECTION, AND Immune FunctionDocument30 pagesVITAMIN A, INFECTION, AND Immune Functionjengki1No ratings yet

- SejarahDocument9 pagesSejarahjengki1No ratings yet

- Neurophysiology WMDocument22 pagesNeurophysiology WMjengki1No ratings yet

- Reliability - Anthro WHO Growth Chart 2006Document9 pagesReliability - Anthro WHO Growth Chart 2006jengki1No ratings yet

- Hearing Loss and Speech DisorderDocument23 pagesHearing Loss and Speech Disorderjengki1No ratings yet

- Investigating Working Memory On SCH AchiveDocument11 pagesInvestigating Working Memory On SCH Achivejengki1No ratings yet

- Childhood Poverty, Chronic Stress On WMDocument5 pagesChildhood Poverty, Chronic Stress On WMjengki1No ratings yet

- Measures of Short-Term Memory: A Historical Review: Special SectionDocument16 pagesMeasures of Short-Term Memory: A Historical Review: Special Sectionjengki1No ratings yet

- Role of Inflammation To WMDocument27 pagesRole of Inflammation To WMjengki1No ratings yet

- Writing - Make A SummaryDocument1 pageWriting - Make A Summaryjengki1No ratings yet

- Intelligence and Educational Achievement PDFDocument9 pagesIntelligence and Educational Achievement PDFLela ZaharaNo ratings yet

- MemoriDocument12 pagesMemorijengki1No ratings yet

- Adaptation PCIT Matos Et Al., 2006Document18 pagesAdaptation PCIT Matos Et Al., 2006jengki1No ratings yet

- MemoriDocument15 pagesMemorijengki1No ratings yet

- Ariana Grande: My InspirationDocument8 pagesAriana Grande: My Inspirationjengki1No ratings yet

- Obligatory and Sunnah FastingDocument20 pagesObligatory and Sunnah Fastingjengki1No ratings yet

- OF ON: Neuropsychiatric Institute School of MedicineDocument7 pagesOF ON: Neuropsychiatric Institute School of Medicinejengki1No ratings yet

- 2011 Non Communicable Diseases in The South East Asia Region PDFDocument104 pages2011 Non Communicable Diseases in The South East Asia Region PDFjengki1No ratings yet

- Physnbioethics 15BWDocument52 pagesPhysnbioethics 15BWjengki1No ratings yet

- Acute Flaccid Paralysis AFPDocument41 pagesAcute Flaccid Paralysis AFPjengki1No ratings yet

- Wma Statement On Child Abuse and NeglectDocument3 pagesWma Statement On Child Abuse and Neglectjengki1No ratings yet

- Daftar SingkatanDocument2 pagesDaftar Singkatanjengki1No ratings yet

- CDC Inmunization ScheduleDocument4 pagesCDC Inmunization ScheduleppoaqpNo ratings yet

- 2021 Medical Biotechnologies ENGDocument14 pages2021 Medical Biotechnologies ENGmahmoud rahmatNo ratings yet

- CCIE Data Center: Written and Lab Exam Content UpdatesDocument5 pagesCCIE Data Center: Written and Lab Exam Content UpdatesFilipi TariganNo ratings yet

- 1st QT Test Research 10Document5 pages1st QT Test Research 10Jezza Marie Caringal100% (1)

- Chomsky's Generativism ExplainedDocument52 pagesChomsky's Generativism ExplainedSalam Neamah HakeemNo ratings yet

- Oral-Comm Q2W1Document6 pagesOral-Comm Q2W1Elmerito MelindoNo ratings yet

- Top Universities in Germany 2017 German University RankingDocument13 pagesTop Universities in Germany 2017 German University RankingVikas AkulaNo ratings yet

- The power of a teacher's personal qualitiesDocument3 pagesThe power of a teacher's personal qualitiesPrincess LopezNo ratings yet

- Artikel 13921-117436-1-PBDocument16 pagesArtikel 13921-117436-1-PBDEDY KURNIAWANNo ratings yet

- June 2013 MSDocument22 pagesJune 2013 MSXX OniiSan XXNo ratings yet

- Practical Exam - Time TableDocument1 pagePractical Exam - Time TableGautam yadavNo ratings yet

- MBA Application For ReferenceDocument31 pagesMBA Application For ReferenceRobert TruongNo ratings yet

- KFC Hero Archetype ProjectDocument3 pagesKFC Hero Archetype ProjectFatima AsimNo ratings yet

- BBC Earth Magazine January 2017 Adventure HackersDocument4 pagesBBC Earth Magazine January 2017 Adventure HackersThames Discovery ProgrammeNo ratings yet

- Affidavit SaiDocument1 pageAffidavit SaiBhargavi BhumaNo ratings yet

- Competency Level: Jofel D. Suan Technical Training SpecialistDocument8 pagesCompetency Level: Jofel D. Suan Technical Training SpecialistJo SNo ratings yet

- Languages of SingaporeDocument20 pagesLanguages of SingaporeLemuel SoNo ratings yet

- Engineering Mechanics Course OutlineDocument3 pagesEngineering Mechanics Course OutlineDedar RashidNo ratings yet

- Gordon AllportDocument10 pagesGordon AllportLouriel NopalNo ratings yet

- S04 Report Race TrackDocument14 pagesS04 Report Race TrackJablanoczki ZsoltNo ratings yet

- The Stepping StoneDocument14 pagesThe Stepping StoneNick Miras LabuguinNo ratings yet

- Advanced Negotiation Skills - Course OutlineDocument9 pagesAdvanced Negotiation Skills - Course OutlineClutch And FlywheelNo ratings yet

- Redcliffe Primary School Maths MEMODocument2 pagesRedcliffe Primary School Maths MEMOThula NkosiNo ratings yet

- DeathDocument31 pagesDeathsara marie bariaNo ratings yet

- Manajemen Keuangan Dan RisikoDocument2 pagesManajemen Keuangan Dan RisikoFilestariNo ratings yet

- Apply Quality StandardsDocument87 pagesApply Quality StandardsMat Domdom V. SansanoNo ratings yet

- University of Melbourne Graduate Prospectus 2021Document72 pagesUniversity of Melbourne Graduate Prospectus 2021Temmy Candra WijayaNo ratings yet

- Student Learning Objectives:: C18Fm - Fundamentals of MarketingDocument4 pagesStudent Learning Objectives:: C18Fm - Fundamentals of MarketingChiTien HooNo ratings yet

- AG - 120362 - Monitor, Report and Make Recommendations Pertaining To Specified RequirementsDocument23 pagesAG - 120362 - Monitor, Report and Make Recommendations Pertaining To Specified RequirementsChristian MakandeNo ratings yet

- Cognitive and Language Development in Children Chi PDFDocument352 pagesCognitive and Language Development in Children Chi PDFMario CordobaNo ratings yet

- Rankers LearningDocument5 pagesRankers LearningrankerslearningNo ratings yet