Professional Documents

Culture Documents

World Water Day 2014 Keynote Speech by Akihiro Ohta, Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (21 March, 2014, The United Nations University, Tokyo, Japan)

Uploaded by

Saghar Asi Awan0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views2 pagesE

Original Title

001215535

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentE

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

5 views2 pagesWorld Water Day 2014 Keynote Speech by Akihiro Ohta, Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism (21 March, 2014, The United Nations University, Tokyo, Japan)

Uploaded by

Saghar Asi AwanE

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

You are on page 1of 2

World Water Day 2014 Keynote Speech

by Akihiro Ohta, Minister of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism

(21 March, 2014, The United Nations University, Tokyo, Japan)

A Complimentary Address to the Opening of World Water Day

I am delighted to welcome Dr. David M. Malone, Rector of the United Nations University, Mr. Michel Jarraud, Chair of

UN-Water, and all attending today’s celebration of World Water Day organized by the United Nations. It is my great pleasure

to welcome His Imperial Highness the Crown Prince of Japan to this ceremony, and I am deeply grateful for the efforts of the

United Nations and other relevant parties to hold the ceremony here in Tokyo. Three years have passed since the Great East

Japan Earthquake, which caused unprecedented damage to Japan. I would like to offer my sincere gratitude to people from

various countries for their warm support for restoration and reconstruction in the interim.

I also acknowledge the great significance of the UN World Water Day; focusing on various aspects of relations between

water and people. I believe the “Water and Energy Nexus,” on which we are focusing this year, is a key theme to note as we

proceed with policies on water.

Today’s attendees tackle various water issues worldwide or are interested in water subjects. Personally, it is a great honor to

have the opportunity to speak to such audience as a representative of Japanese water administrator.

Japanese Concept of Water: Mujo and Joju

(1) Water and “Mujo”

Japan lies at the eastern edge of the Monsoon Asia, one of the rainiest regions on Earth, with an annual rainfall of about

1,700 millimeters. This is about twice the global average, and Japan tends to be considered a country with rich water

resources. However, since the country extends east-west and south-north, with a total length of about 3,000 km respectively

and mountains beyond 2,000 m elevation run through the middle of the land, the rainfall varies according to regions and

seasons, and the steep topography forces rainwater to instantly flow seawards.

This means water resources in Japan have distinctive characteristics: huge labor is required to stably ensure water resources

nationwide while short-term heavy rainfall often causes flooding that holds significant energy.

As such, Japan is a country at high risk of and prone to natural disasters, such as water-related disasters and earthquakes.

As Japanese have witnessed natural forces that are beyond human control, concepts of “Mujo” and “Joju” have emerged.

The term “Mujo” means everything is repeatedly emerges, ceases and ceaselessly changes. The transience of human lives,

which are easily taken away by natural disasters, including typhoons and tsunamis, and the resulting upheaval imposed,

correlate to events generating the “concept of Mujo.” In the 13th century, Chomei Kamono wrote about disastrous

circumstances involving many fatalities in earthquakes, flooding, and drought, which occurred successively as a disaster

record in his essay “Hojoki.” He grieved and lamented what had happened and opened his essay by comparing people and

their dwellings to the flow of rivers and foam at the beginning. He says, “The flowing river never stops and yet the water

never stays the same. Foam floats upon the pools, scattering, re-forming, and never lingering long.”1 He tried to say

everything in the world is ceaselessly changing, “Mujo” and frail.

(2) Intersection between “Mujo” and “Joju”

Conversely, the term “Joju” illustrates a concept opposite to “Mujo,” namely no change, constant existence, and something

everlasting. Human beings tend to deny the concept of “Mujo” in considering their daily lives and the future and pursue

“Joju,” while desiring the latter is what it should always be.

Accordingly, we are located between Mujo and Joju, and living and swinging on the “infinite” points between both worlds.

Japanese have found a “halfway house” between “Mujo” and “Joju” in harsh nature and learned how to compromise with

water and create our water culture while accumulating experiences and technologies in our long history.

In the “Water and Energy Nexus,” today’s theme, Japanese have not sought “Joju” beyond “Mujo” but rather tried to

realize “Joju” in “Mujo.” In other words, we tried to find an intersection between “Mujo” and “Joju” to lead an affluent life.

Water Technologies of which Japan is Proud

Based on such water concept, Japanese people have long since striven to reduce repeated flooding and drought disasters by

applying home-grown ideas, which has seen them acquire various types of techniques based on soothing rivers and

compromising and coexisting with nature instead of trying to control rivers. For example, we “relocated the floodway of the

1

Hojoki: Visions of a Torn World by Kamo-no Chomei. Translated by Yasuhiko Moriguchi and David Jenkins; illustrated by Michael Hofmann. Berkeley: Stone

Bridge Press, 1996

Tone river to the east,” paving the way for the present-day prosperity of Tokyo. Originally, the Tone River flew into Tokyo

bay and repeatedly flooded. The early years of the Edo Period in the 1600s saw large-scale river construction commence: it

took about 60 years to relocate the river eastwards to circumvent Tokyo and directly channel it into the Pacific. Japanese

turned “misfortune” into “blessing” by diverting the massive energy of water away from Tokyo, and enabling the

development of new rice fields, ship transportation, and urban land use.

Moreover, since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when Japan started its modernization history, it developed water resource

facilities, including dams, to satisfy new water demand while pursuing national development and powers. The hydroelectric

power generated by the dam boosted energy demand during the post-war recovery years and remains an important source of

clean energy. In recent years, Japan has tried to introduce and promote hydroelectric power using compact facilities that only

require limited water and are available at many places, rather than solely depending on large-scale facilities.

In addition, coverage of the water-supply system improved by securing water resources for municipal water, whereupon

living standards soared. Women were released from heavy water-related work and could join social activities as well as

providing safe tap water to slash infant mortality. Nowadays in Japan, the water-supply system coverage exceeds 97% and the

tap water is of sufficient quality for both non-Japanese and Japanese to drink directly nationwide. Water treated by the

top-quality water cleaning system enjoys a high reputation as tasty water and is also sold in pet bottles.

This relationship with water can be explained in the context of various characteristics of Japanese water culture as follows:

- Festivals to beg for rain, flood/plague prevention and abundant harvest because according to the religion of the

Japanese water god, god’s spirit dwells in water,

- The rice paddy culture, a cornerstone of Japan, because rice production supporting the Japanese diet reflects

typical water use,

- Landscape expressed in the term “scenic beauty” of clean and beautiful water,

- Food culture designated as a form of Intangible World Cultural Heritage, because Japan is blessed with water of

good quality.

However, human behavior does not always elicit good results and the rapid socioeconomic growth after World War II

considerably burdened the environment. In the early 1960s, the Sumida river, Tokyo’s symbol, became a “death river” due to

water pollution. People thus strove very hard to develop a sewage system and boost water quality throughout Japan, following

which a regatta was regularly conducted on the Sumida River from 1978, and a fireworks display conducted every summer

became a key national event.

These examples show how the proliferation of the sewage system played a key role in improving living standards, while

recent years have seen efforts to achieve a low-carbon society, including the use of sewage sludge and heat as renewable

energy sources.

Besides, we must also count the impacts of global climate change. Recently, disasters in Japan have become more

localized, concentrated, and devastating than previously. These phenomena may intensify, and we must enhance our ability to

prevent and mitigate disasters by predicting the upcoming future. Amid such circumstances, Japanese have tried to develop

advanced technologies, e.g. observation and forecasting systems exploiting infocommunications technology and “upgrading

dams” that strengthen flood-control functions without disturbing existing functions.

International Contribution Based on Experiences in Japan

Japanese have been building water technologies by facing up to and learning from nature as well as working on land. I

hope these technologies, including processes, are profitable in global water-related efforts.

Japan has been providing support to solve problems related to water, sanitation, and disasters through international dialog,

including the “United Nations Secretary-General’s Advisory Board on Water and Sanitation” and “World Water Forum”,

international cooperation by optimally exploiting our experiences and achievements, and collaboration between the public

and private sectors. We will continue to provide support with our water technologies and solve global water problems.

Expectations for the Ceremony

Finally, I expect the message transmitted from this ceremony to the world will significantly boost global water-related

efforts.

Thank you for your kind attention.

(Translated by Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism, Japan)

You might also like

- Board of Intermediate and Secondary Education, SahiwalDocument2 pagesBoard of Intermediate and Secondary Education, SahiwalSaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- Data Analysis of Students Marks With DesDocument4 pagesData Analysis of Students Marks With DesSaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- What Is The Relationship Between Marks and Educational Expectations?Document7 pagesWhat Is The Relationship Between Marks and Educational Expectations?Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- Maryam Afzal 5045Document5 pagesMaryam Afzal 5045Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- Exam in Elctiv SubjectDocument1 pageExam in Elctiv SubjectSaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- Biochemistry of MuscleDocument16 pagesBiochemistry of MuscleSaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

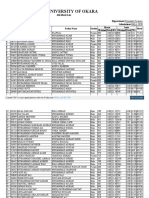

- University of Okara: 1st Merit List Department:Computer Science Admissions:FALL 2020Document6 pagesUniversity of Okara: 1st Merit List Department:Computer Science Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- University of Okara: 5th Merit List Department:Computer Science Admissions:FALL 2020Document5 pagesUniversity of Okara: 5th Merit List Department:Computer Science Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- University of Okara: 4th Merit List Department:Computer Science Admissions:FALL 2020Document6 pagesUniversity of Okara: 4th Merit List Department:Computer Science Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

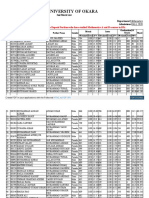

- University of Okara: 2nd Merit List Department:Computer Science Admissions:FALL 2020Document5 pagesUniversity of Okara: 2nd Merit List Department:Computer Science Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- 95th Merit List M.SC PU Fall 2020-IBBDocument1 page95th Merit List M.SC PU Fall 2020-IBBSaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- Deoband MovementDocument2 pagesDeoband MovementSaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- University of Okara: 3rd Merit List Department:Computer Science Admissions:FALL 2020Document5 pagesUniversity of Okara: 3rd Merit List Department:Computer Science Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- Master Status in Sociology: de Nition & ExamplesDocument7 pagesMaster Status in Sociology: de Nition & ExamplesSaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- University of Okara: 2nd Merit List Department:Physics Admissions:FALL 2020Document3 pagesUniversity of Okara: 2nd Merit List Department:Physics Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- University of Okara: 8th Merit List Department:Physics Admissions:FALL 2020Document2 pagesUniversity of Okara: 8th Merit List Department:Physics Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- University of Okara: 4th Merit List Department:School of Law Admissions:FALL 2020Document2 pagesUniversity of Okara: 4th Merit List Department:School of Law Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- University of Okara: 9th Merit List Department:Physics Admissions:FALL 2020Document3 pagesUniversity of Okara: 9th Merit List Department:Physics Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- University of Okara: 5th Merit List Department:School of Law Admissions:FALL 2020Document2 pagesUniversity of Okara: 5th Merit List Department:School of Law Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- University of Okara: 9th Merit List Department:Chemistry Admissions:FALL 2020Document2 pagesUniversity of Okara: 9th Merit List Department:Chemistry Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- University of Okara: 2nd Merit List Department:Mathematics Admissions:FALL 2020Document5 pagesUniversity of Okara: 2nd Merit List Department:Mathematics Admissions:FALL 2020Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- Welcome To Biochemistry Section A1!: Biochemistry Is The Chemistry of Living MatterDocument2 pagesWelcome To Biochemistry Section A1!: Biochemistry Is The Chemistry of Living MatterSaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- Sir Syed Ahmad Khan: A Prophet of Education and Champion of Hindu-Muslim UnityDocument5 pagesSir Syed Ahmad Khan: A Prophet of Education and Champion of Hindu-Muslim UnitySaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- 12 Syed PDFDocument14 pages12 Syed PDFSaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- Deed of Agreement: SPECIMEN (1 Pages)Document3 pagesDeed of Agreement: SPECIMEN (1 Pages)Saghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- 1 IntroThermoDocument9 pages1 IntroThermoSaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- WWW Britannica Com Science BiochemistryDocument13 pagesWWW Britannica Com Science BiochemistrySaghar Asi AwanNo ratings yet

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5795)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (588)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1090)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (121)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- DRR Week 1 - 2Document15 pagesDRR Week 1 - 2Aleli Joy Profugo Dalisay100% (1)

- Flood Susceptibility Map of Cagayan de Oro City, Misamis OrientalDocument1 pageFlood Susceptibility Map of Cagayan de Oro City, Misamis OrientalEm NueraNo ratings yet

- Week 8 CU 7 DN-M2-CU7 School Mitigation and Preparedness, Evaluation-2 - 1460360581 PDFDocument9 pagesWeek 8 CU 7 DN-M2-CU7 School Mitigation and Preparedness, Evaluation-2 - 1460360581 PDFArlyn MarcelinoNo ratings yet

- Mid Day All India Weather Summary and Forecast Bulletin: Tuesday 19 July 2022 Time of Issue: 1300 Hours ISTDocument17 pagesMid Day All India Weather Summary and Forecast Bulletin: Tuesday 19 July 2022 Time of Issue: 1300 Hours ISTV.Dharun 6 ANo ratings yet

- Disaster Relief - Provision and ProcedureDocument34 pagesDisaster Relief - Provision and ProcedureAmlan MishraNo ratings yet

- Example of Thesis Chapter 1 - 3Document30 pagesExample of Thesis Chapter 1 - 3kenNo ratings yet

- Typhoon Contingency Plan - Tarlac Province Cy 2022 - 2025Document66 pagesTyphoon Contingency Plan - Tarlac Province Cy 2022 - 2025Christian Bonne MarimlaNo ratings yet

- University of Caloocan City College of Business and AccountancyDocument3 pagesUniversity of Caloocan City College of Business and AccountancyKenneth BulanNo ratings yet

- Explanation: For Xi Grade Semester 2Document12 pagesExplanation: For Xi Grade Semester 2Furay LulayNo ratings yet

- Hydrometeorological Hazards 2020-2021Document29 pagesHydrometeorological Hazards 2020-2021Jessa Espiritu100% (1)

- Foundation Failure in The PhilippinesDocument15 pagesFoundation Failure in The PhilippinesMALABANA, Charlize Joy C.100% (1)

- Tracking The Tropical CycloneDocument1 pageTracking The Tropical CycloneMARY JANE CORPUSNo ratings yet

- Emergency Preparedness GuidebookDocument46 pagesEmergency Preparedness Guidebookallen_holly100% (1)

- Chapter 4 DRRRDocument27 pagesChapter 4 DRRRbeth alviolaNo ratings yet

- A Case Study of Community-Based Vulnerability Mapping in MexicoDocument1 pageA Case Study of Community-Based Vulnerability Mapping in MexicoRatan SikderNo ratings yet

- Skrip Oral CommentaryDocument2 pagesSkrip Oral CommentaryNur SalNo ratings yet

- Sample Emergency Evacuation PlanDocument4 pagesSample Emergency Evacuation Planapi-510201900No ratings yet

- 01 - LEC - Disaster NursingDocument5 pages01 - LEC - Disaster Nursingericka abasNo ratings yet

- NCERT Solutions Class 9 English Supplementary Chapter 6 Weathering The Storm in ErsamaDocument2 pagesNCERT Solutions Class 9 English Supplementary Chapter 6 Weathering The Storm in ErsamaManoj RoyNo ratings yet

- Disaster Risk Reduction and Disaster Risk Management BrochureDocument1 pageDisaster Risk Reduction and Disaster Risk Management BrochureCybelle Samson GapasNo ratings yet

- 4th QUARTER EXAMINATION in DRRDocument4 pages4th QUARTER EXAMINATION in DRRGold Aziphil Galiza100% (3)

- Initial Research - Persuasive EssayDocument7 pagesInitial Research - Persuasive EssayJhealsa Marie CarlosNo ratings yet

- Analisis Kesiapsiagaan Masyarakat Kota Padang Dalam Menghadapi Bencana Alam SupraptoDocument12 pagesAnalisis Kesiapsiagaan Masyarakat Kota Padang Dalam Menghadapi Bencana Alam Supraptofajri valentinoNo ratings yet

- BCM Guide 2020 FinalDocument88 pagesBCM Guide 2020 FinallclaudioNo ratings yet

- Civil Aviation Authority of The Philippines Aircraft Accident Investigation and Inquiry Board Aircraft Accident ReportDocument2 pagesCivil Aviation Authority of The Philippines Aircraft Accident Investigation and Inquiry Board Aircraft Accident ReportBenedict CarandangNo ratings yet

- Flooding Impacts On The Bridges - An OverviewDocument7 pagesFlooding Impacts On The Bridges - An OverviewShahbaz ShahNo ratings yet

- Disaster Management Complete Lecture NotesDocument127 pagesDisaster Management Complete Lecture Notesirene oget otienoNo ratings yet

- Batangas State University Batstateu Alangilan: Republic of The PhilippinesDocument16 pagesBatangas State University Batstateu Alangilan: Republic of The PhilippinesZiyouNo ratings yet

- What Is Global WarmingDocument16 pagesWhat Is Global Warmingmanishsingh62700% (1)

- Oedipus Rex by Sophocles Aristotle AnalysisDocument1 pageOedipus Rex by Sophocles Aristotle AnalysisSarita SalvadorNo ratings yet