Professional Documents

Culture Documents

Using Ipads and Seesaw For Formative Assessment in K2 Classrooms

Uploaded by

MARIANA ISABEL PEINADO NAVARROOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Report this DocumentCopyright:

Available Formats

Using Ipads and Seesaw For Formative Assessment in K2 Classrooms

Uploaded by

MARIANA ISABEL PEINADO NAVARROCopyright:

Available Formats

1

Using iPads and Seesaw for Formative Assessment in K2 Classrooms

Trish Harvey

School of Education, Hamline University, St. Paul, MN, USA

tharvey03@hamline.edu

651-523-2532

@trishlharvey

Trish Harvey is a professor in the School of Education with an emphasis in Advanced Learning

Technologies at Hamline University. Trish’s background includes over 18 years of K-16

experience including teaching social studies, advising graduate students, and serving as a digital

learning administrator. Focus areas of research include: the use of digital tools for

learning/assessment, fostering quality online learning experiences, and educational

transformation via policy and technology.

Abstract

A case study of K2 classrooms in five elementary buildings was conducted to explore the usage

of iPads. Participants shared their use of Seesaw for formative assessment and their beliefs about

technology creating equitable chances for students. Data collection methods included survey

data, classroom observations, interviews and Seesaw artifacts. Results indicated that iPads and

Seesaw are appropriate and efficient tools for collecting formative assessment data in K2

classrooms. Results also indicated that technology can achieve equity when personalized to meet

students needs.

Keywords: iPads, Seesaw, digital learning, formative assessment

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

2

Using iPads and Seesaw for Formative Assessment in K2 Classrooms

Introduction

In the spring of 2018, I was granted a release from my faculty position to spend the semester in

an urban school district where iPads are provided to every student. I was interested in conducting

a study on the relationship between formative assessment and the use of iPads; the district was

interested in learning how K2 teachers were utilizing Seesaw, a digital portfolio platform

recently purchased by the district. It was a perfect opportunity to investigate teacher use of iPads

and Seesaw with a focus on formative assessment. There were a number of questions that guided

my study, my primary question was: What is the impact of using Seesaw and iPads to collect

formative assessment data in K2 classrooms? Secondary questions included: In what ways can

the use of digital tools for formative assessment support creating an equitable environment where

all learners are supported in reaching learning outcomes? How are teachers using Seesaw to

collect formative assessment data? How does the data collected using Seesaw inform instruction?

How are student’s individual learning needs assessed using Seesaw? How do students interact

with Seesaw and the iPads?

According to the school district, K-2 classroom teachers were having a difficult time

utilizing the district’s learning management system (LMS), Schoology. This LMS was perceived

as too text-based for their students. Therefore, the district purchased Seesaw for grades K2,

which allowed for easier collection of student work. The implementation of Seesaw allowed for

an opportunity to do data collection around usage of this digital tool related to student learning.

In my work with graduate students in the field of education, I work with K12 teachers in

all content areas pursuing degrees in education, literacy, and environmental education. I work

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

3

with teachers from large and small schools, metro and rural schools, and diverse and

homogenous schools. A constant observation of my graduate students is the varying integration

of technology from one school to the next. Sometimes the integration can even vary greatly from

one classroom to the next. I approach this work believing that incorporating technology should

no longer be optional for school districts and/or teachers; and I would argue that the haphazard

implementation of digital tools has further increased the inequity in classrooms.

My research agenda for the past 5-6 years has been focused on how to leverage

technology to increase student learning. Prior to my current university position, I served as a

digital learning coordinator for a suburban school district in the Twin Cities metro area and

researched the impact of iPads on student engagement and student learning across the K-12

environment. In my current position, I have expanded this research agenda to include using

digital tools for formative assessment.

In partnership with the school district, my goal was to help the district in meeting their

goal of personalized learning that is “student-centered, customizable, and technology enriched”

and utilizes the district 1:1 iPad initiative for all students. Personalized learning allows the pace

and pathway to learning to be determined by the student. By focusing on formative assessment

instead of test scores/summative assessments, teachers identify individual student needs (Black

& Wiliam, 2001). Meeting an individual student’s needs creates more equitable chances for all

students. The purpose of this study is to assess how teachers are using Seesaw for formative

assessment in K2 classrooms and if this usage creates more equitable learning environments.

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

4

Literature Review

SAMR model

Ruben Puentedura (2013) developed a technology integration model, SAMR, to contemplate

technology integration and lesson design. According to the model, there are four levels of

implementation:

● Substitution: At this level of integration, technology replaces an action that could take

place in the classroom without technology. For example, the technology may be used to

type something that could be written by the students. The design of the task does not

change because of the technology.

● Augmentation: At this level, the technology use slightly improves something that could

have been done without technology. For example, instead of writing something by hand,

students type in a word processing program that corrects spelling and grammar mistakes.

● Modification: In the modification level, technology allows for tasks to be significantly

redesigned. These are students tasks that could not happen without the technology. For

example, elementary students produce video-based book reviews and place QR codes on

library books linking to their videos.

● Redefinition: Redefinition is the highest level of technology integration. At this level,

technology allows for tasks, previously inconceivable without the technology, to be

designed. For example, two high school science classrooms in different parts of the world

perform lab experiments, share the data and write lab reports together.

At the highest levels, teachers consider ways of teaching that simply could not be

possible without technology in the classroom. The SAMR model provides a way to assess the

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

5

level of technology integration in classrooms. For this study, it provided a way to analyze tasks

observed in the classrooms and collected in Seesaw.

Seesaw

Seesaw is a digital portfolio app, “Students can use photos, videos, audio recordings, drawings,

text or links to add evidence of what they’re learning” (Shields, 2017, p. 109). The paid version

of Seesaw for schools allows districts and teachers to upload state, district or grade-level

standards. Assignments and submissions can be aligned to these standards. And teachers can also

assess student work in the application based on the standards.

Seesaw is an age and ability level appropriate app for grades K-5 which helps to engage

digital learners (Lacey, Gunter, & Reeves, 2014). Reeves, Gunter and Lacey (2017) found the

combination of informed student feedback and the integration of mobile technology in

content-specific areas increases early childhood academic achievement. Seesaw allows teachers

to provide informal feedback; and the student work submitted can help inform teachers and

instruction.

The district was in their first formal year of district-wide K2 implementation of Seesaw.

Two schools had piloted the app in the previous year.

Formative assessment

Formative and summative assessment are the two types of assessments used by classroom

teachers to gauge student learning and to inform instruction. Formative assessments are informal

but planned activities that provide feedback on student progress with content. Examples include

homework assignments, quizzes, exit tickets, classroom discussion, and/or quick checks for

understanding. Formative assessments are typically not graded and are utilized to inform

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

6

day-to-day instruction in the classroom. Hattie (2012) identified formative assessment as one of

the top ten practices to increase student achievement. Summative assessments are the final, end

of unit assessments. Examples include tests, final projects, and final papers. These assessments

are typically graded by instructors.

A strong research base (Black & Wiliam, 2001; Hattie, 2012; Marzano, 2007; Popham,

2008) supports the role of formative assessment in increasing student achievement. Formative

assessment with its “emphasis on sense-making” supports learners in becoming “metacognitive”,

which is a higher order thinking skill (Bransford, Brown & Cocking, 2000, p. 137) and is an

essential 21st century learning skill (Partnership for 21st Century Skills, 2016). Unfortunately,

the same authors (Bransford et al., 1999; Hunt & Pellegrino, 2002; Popham, 2008) who argued

for the important role of formative assessment in increasing student achievement also pointed out

its absence in actual classroom practice.

Formative assessment and the digital divide

While digital tools by themselves are not formative assessment, they can be used to make

it easier for both teachers and learners to engage in frequent formative assessment during actual

learning (Beatty & Gerace, 2009). There are several advantages in using digital tools to collect

formative assessment in the classroom, including: (1) digital tools efficiently score student work

and create an accessible, permanent record, (2) digital tools are engaging for students, and (3)

digital tools efficiently provide assessment results to both teachers and students.

The literature on formative assessment makes a clear connection between increased

student learning and teachers use of formative assessment data. Furthermore, the literature on

formative assessment and the “digital divide” asserts that when technology is used in the learning

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

7

process to identify students’ needs and to personalize the learning experience, the digital divide

decreases. Black and Wiliam (1998) found that formative assessment may be the most significant

factor in increasing academic achievement, especially for low-achieving students.

Darling-Hammond, Zielezinski and Goldman (2014), in a meta-analysis of over 70

studies involving technology in the classroom, found that technology can close the opportunity

gap and improve learning outcomes for at-risk students when digital tools are “implemented

properly”. Proper implementation of digital tools has been the subject of many discussions

(Barron, Bofferding, Cayton-Hodges, Copple, Darling-Hammond & Levine, 2011; Couros,

2015; Darling-Hammond, Zielezinski, & Goldman, 2014) - common themes include: teachers

need to provide interactive learning opportunities, the technology needs to be used for creation

and explorations vs. skill and drill activities, and the classroom teacher plays a vital role in

facilitating the learning process.

Warschauer, Knobel and Stone (2004) found that in order to close the opportunity gap

between low- and high-SES schools, one solution should be a focus on how technology is

leveraged. Attention must be given to “scholarship, research and inquiry” when using digital

tools (p. 586). When the technology is used to better understand individual student needs related

to learning outcomes and standards, the teacher can facilitate better mastery of the content

(Mohammed, 2017). Therefore, a focus on formative assessment and digital tools provides the

means to this end.

Methods

A case study approach was used to answer the primary research question, What is the impact of

using Seesaw and iPads to collect formative assessment data in K2 classrooms? As identified by

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

8

Yin (2018), case study methodology allows the researcher to view events from a real-world

perspective. In this case, I was able to view how K2 classrooms were using digital learning by

sitting in classrooms, attending meetings, and watching students. The study took place in K2

classrooms at five urban elementary buildings. Once approval was granted from the school

district and I received IRB approval to conduct my study, I spent four months shadowing “Tina”,

the Senior Specialist Apple Professional Learning. Tina had worked for the district since iPads

had been implemented district-wide three years earlier. The district paid her consultant fee to

support digital integration efforts. Tina was assigned to several different buildings throughout the

district (ranging between 10-12 buildings/year). The five elementary buildings in this study were

included in Tina’s assignment. My time with Tina included attending team level meetings,

participating in classroom instruction, observing teachers, attending professional development

sessions, and meeting with building administrators and individual classroom teachers. Table 1

depicts the demographic makeup of each school.

Table 1

School demographic information.

School School A School B School C School D School E

Enrollment 451 459 186 451 341

Students who identify themselves as:

American Indian 3% 1% 0% 3% 0%

Asian American 37% 20% 41% 11% 36%

African American 34% 46% 13% 15% 30%

Hispanic American 14% 14% 12% 6% 12%

White American 12% 18% 34% 65% 11%

Students in English Language Learning 43% 39% 30% 11% 42%

Students in Special Education 14% 16% 5% 4% 17%

Students eligible for Free & Reduced Lunch 79% 84% 25% 28% 78%

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

9

The data collection methods included observations, surveys, interviews and Seesaw

artifacts. I conducted observations of team meetings and classrooms. I attended a minimum of

one team meeting per grade level at each building. These meetings were facilitated by Tina and

were aligned to school and grade level technology goals. Four of the five schools had regularly

scheduled monthly meetings. There were no regularly scheduled meetings at School B. Data

collected from team meetings included the type of technology support requested and supported,

the level of engagement of meeting participants, and the goals of each classroom for using digital

tools. During classroom observations, student engagement, the level of technology integration,

and the use of formative assessment were observed and recorded. I conducted eight classroom

observations.

A survey was emailed to all K2 teachers in the five schools. Teachers were reminded

during team meetings to complete the survey. The purpose of the survey was to gain teacher’s

perceptions of formative assessment, seesaw usage and teacher comfort with technology in the

classroom. Twenty-five teachers completed the survey; the survey was emailed to forty-five

teachers. Interviews were conducted with sixteen teachers; all sixteen volunteered via the survey

to be interviewed for the study. The interview data provided additional explanations for survey

responses and provided classroom examples of Seesaw and formative assessment.

The last data tool utilized as Seesaw data. Artifacts, including examples of student work,

were collected. Seesaw usage was also reviewed. This data helped identify the teachers who used

Seesaw regularly in the classrooms. Additionally, student artifacts were analyzed as formative or

summative assessments and in connection to learning outcomes.

Results

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

10

Survey results

When surveyed about formative assessment in the classroom, all participants believed they use

formative assessment (see Table 2). The majority believed they used it to inform instruction, to

provide feedback to students, and to identify individual student needs. The only two areas

showing lower levels of agreement were in using iPads for formative assessment and in having

students self-assess their own learning using formative assessment.

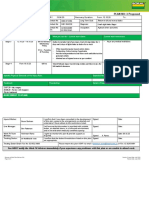

Table 2

Formative Assessment Usage in the Classroom - Teacher Survey Responses (n=25)

I use I use iPads for I use I use I use formative I use formative

formative formative formative formative assessment to assessment in the

assessment assessment in assessment to assessment identify classroom that allows

in the the classroom. inform my to provide individual students to self-assess

classroom. instruction. feedback to student needs. their own learning.

students.

Strongly 10 (40%) 2 (8%) 11 (44%) 7 (28%) 9 (36%) 5 (20%)

Agree

Agree 15 (60%) 15 (60%) 13 (52%) 16 (64%) 15 (60%) 14 (56%)

Disagree 0 8 (32%) 1 (4%) 2 (8%) 1 (4%) 6 (24%)

Strongly 0 0 0 0 0 0

Disagree

The Seesaw usage survey questions showed agreement with teachers’ comfort with

Seesaw and usage in the classroom (see Table 3). While the majority of teachers agreed with the

comments “I use Seesaw often in the classroom”, the word “often” was not operationally defined

and “usage” did not necessarily correlate to student usage when reviewing Seesaw statistics. The

connection between Seesaw and formative assessment showed a third of teachers not using

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

11

Seesaw for formative assessment and almost one half of teachers not using Seesaw to provide

feedback to students.

Table 3

Seesaw Usage in the Classroom - Teacher Survey Responses (n=25)

I feel I use Seesaw I use Seesaw I identify learning I provide feedback

comfortable often in the for formative outcomes in Seesaw to students in

using Seesaw. classroom. assessment. related to student work. Seesaw.

Strongly 6 (24%) 8 (32%) 5 (20%) 4 (16%) 4 (16%)

Agree

Agree 17 (68%) 15 (60%) 12 (48%) 16 (64%) 9 (36%)

Disagree 1 (4%) 2 (8%) 7 (28%) 5 (20%) 12 (48%)

Strongly 1 (4%) 0 1 (4%) 0 0

Disagree

Teacher survey responses regarding digital learning in the classroom revealed strong

agreement across all categories (see Table 4). All participants agreed that students were

comfortable with digital tools and the teachers were comfortable using iPads. Based on

classroom observations, being comfortable using iPads did not correlate to actually using iPads

in the classroom with students.

Table 4

Digital Learning Usage in the Classroom - Teacher Survey Responses (n=25)

I am comfortable My students are I am comfortable I believe digital

using digital tools comfortable using digital using iPads in the learning creates a

in the classroom. tools for learning in the classroom. more equitable

classroom. classroom.

Strongly Agree 2 (8%) 2 (8%) 7 (28%) 4 (16%)

Agree 22 (88%) 23 (92%) 18 (72%) 18 (72%)

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

12

Disagree 1 (4%) 0 0 3 (12%)

Strongly Disagree 0 0 0 0

Observations

I conducted two classroom observations at School A. According to Tina, the principal considered

themself to be “techy” and regularly modeled technology during staff meetings - including the

use of Nearpod, an interactive slideshow application. Both classrooms were using Clips (iOS

Apple application for making videos) to create an animal report which would be uploaded to

Seesaw. Prior to the lesson, students had saved images to their iPads and had handwritten notes

from researching their animal. Although the lesson was the same in both classrooms, I observed

one classroom with habits, processes, and procedures for using iPads, while the second

classroom had few iPad procedures. Based on observed student behavior and student questions,

it appeared that the iPads were used infrequently in the second classroom. While the first teacher

would be able to use the final animal report uploaded to Seesaw to assess student learning and

understanding of the content, the reports created in the second classroom would be compromised

by the technology barriers observed. The second classroom encountered a number of technology

challenges that would distract from the quality of the final product. Both products were

summative assessments.

School B did not have regularly scheduled team meetings with Tina. The building was

supported by two staff members with strong digital learning skills. No classroom observations

were conducted (no teachers volunteered to have a lesson observed when completing the survey).

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

13

School C demonstrated high levels of engagement during observed team meetings.

Teachers arrived on time, asked questions, and sought support for activities in their classrooms.

During one team meeting, I observed team members high comfort with technology as they

air-dropped documents between each other and shared examples of student work at modification

and redefinition levels. Tina shared that School C was both a STEM (Science, Technology,

Engineering and Mathematics) school and a language immersion academy. Tina also shared that

the principal regularly attended team meetings. Interview data and Seesaw artifacts aligned to

observed behaviors in team meetings and in classrooms. Five classroom observations were

conducted in School C. Two second grade classes were combined to build a Keynote

presentation on Chinese foods and culture. The final product would be a summative assessment.

Students were engaged and on-task. Students were very comfortable with the iPads and eager to

learn a new app (Keynote). The first grade classrooms were observed for a combined project

using Keynote for “How To” projects. The Keynote app had not been installed on student iPads

and the lesson proved challenging without hands-on opportunities for students. Student iPads are

managed by the district and advanced planning is required to use a new app, which can be a

hurdle for teachers wanting to use a new app in the classroom. Students were attentive and

well-behaved but nothing was produced. The final “How To” product would be a summative

assessment. One kindergarten classroom was observed. Students were using Bookcreator to

create “All About Me” books. Students were on-task, the only difficulty in relation to text and

writing names. The final book product was a summative assessment.

At team meetings in School D, there were at least two instances when teams did not show

up. During the majority of the meetings, the grade level teams worked on completing “Apple

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

14

Badges”, achieved by completing quizzes on tools within the Apple ecosystem. One grade level,

when meeting with Tina, appeared to be both confrontational about implementing technology but

also eager to learn. These were the two classrooms that I observed in School D. Both teachers

had worked in the district for 20+ years and their students had been highly successful on state

standardized tests for math and reading. These teachers were hesitant to change what was

working in their classrooms while also understanding the need to integrate technology into their

classrooms. I observed the same lesson in both classrooms using the iMovie app to create “All

About Me” videos. The students were attentive and on-task. The final products were uploaded to

Seesaw as summative assessments

School E had been a pilot school in the district for Seesaw under a previous principal.

The principal of the school during my research did not promote the use of technology as strongly

as his predecessor. I observed technology team meetings that were poorly attended and lacked

engagement. For example, at every meeting, I observed at least one of the following behaviors:

teachers did not attend, arrived late, showed up without any technology, and/or ate their lunch

during the meetings. I conducted three classroom observations at School E. The first observation

took place during a second grade reading lesson. The class read a story together and completed a

reader-response activity (“I think the author’s message is ____ because _____”) on the iPad and

submitted it to Seesaw. I observed students take advantage of flexible seating around the

classroom to complete the assigned work. I did not observe any students off task or on the wrong

iPad app. The second observation was conducted in a first grade math classroom. The class met

in the front of the room to discuss a new concept related to fractions. They returned to their seats

to complete a workbook assignment. When asked what to when finished, the class responded in

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

15

unison, “Take a picture and sent it to Seesaw.” The students were on-task and it was observed

that routines had been clearly established for using technology to submit assigned work. The

final observation at School E took place in a first grade math classroom working on counting

money. When students met in the front of the room to learn the new concept, they had a choice

of working on an iPad or a whiteboard (see Figure 1). Students were assigned to rotating stations

to practice skills and practice work was uploaded to Seesaw. This approach met the needs of this

high energy class.

Figure 1. 1st grade math students using iPads and whiteboard to practice math problems.

The SAMR model is a way to categorize how technology was used in by teachers in the

study. Several projects, including the All About Me books, the Animal presentations, and the

How To presentations represented lower levels of SAMR. The tasks were at the Substitution and

Augmentation levels. The final products were improved by the use of technology but not

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

16

dependent on the use of technology. A number of products did fall under the Modification level,

including the movies students created. The tasks were dependent on the use of technology. The

overall use of Seesaw as a way to share the final products with the teacher, classmates and

parents/guardians moves many of these tasks to the Modification level. I did not observe any

tasks at the Redefinition level of SAMR.

Interviews

I conducted sixteen interviews between February and May of 2018. (Number of interviews per

building: School A: 2, School B: 2, School C: 5, School D: 3, School E: 4.) Interviews consisted

of ten fixed, structured questions and lasted between 25-60 minutes dependent upon the length of

the interviewee’s responses. Interviewees were categorized into two categories in relation to

iPads and technology in the classroom — 1) eager to learn about digital learning and daily users

of iPads in their classrooms, and 2) skeptical of technology and limited users of iPads in the

classroom. Twelve interviewees fell into the “eager” category and four were “skeptical.” These

discussions shed more light on how iPads and Seesaw were used for formative assessment. Eight

interviewees used Seesaw daily to collect formative assessment data. Examples include daily

math exit slips, reader-response prompts and responses, drafts of writing assignments, and math

assignments where students recorded their explanation of the answer.

Teachers were asked to explain challenges and celebrations in technology integration in

the classroom. The top four shared challenged included: 1) technical issues including apps not

downloaded, students being logged out of their devices, internet issues, and devices not being

charged, 2) not adequate time and training for teachers, 3) students having difficulty with typing

and/or using text in early grade levels, and 4) background class noise when students are

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

17

recording audio or video. A shared celebration by the majority of interviewees was the visibility

of student work to teachers, other students and parents/guardians in Seesaw. One teacher

comment reflects this collective response, “Seesaw...allows parents to see where their kids are.

So they don’t have to wait until report card time.”

When interviewees were asked about feeling well prepared to integrate technology into

their classrooms, ten of the respondents said they felt prepared and attributed it to the extra time

they had spent outside of school to learn how to use the technology. Age and years of experience

were not factors in feeling prepared, one teacher commented, “I am excited about using

technology. I like the idea and I’m ready for that. I’ve been teaching for 30 years so I’ve gone

from chalkboards to whiteboards to all different technology we’ve had.” Another respondent’s

answer depicts this shared sentiment between veteran interviewees, “...even I say that I’m old but

I am still willing to learn anything that is new and helpful for the kids.”

When asked what role administrators and other building leaders should play in assisting

teachers in their use of technology, there was consensus between respondents that additional

training and professional development opportunities were needed. Fourteen of the respondents

commented on the need to have more iPad and Seesaw training. Additionally, several

interviewees discussed the value of working collaboratively with other teachers who were using

technology in their classrooms.

Discussion

Based on my study of these five elementary buildings, one conclusion is that Seesaw is the

correct iPad app for collecting formative assessment in grades K-2. The app has the ability to

collect student work at all stages of student learning. Standards and skills can be uploaded to the

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

18

paid version of Seesaw. Figure 2 shows an example of a first grade classroom using Seesaw to

collective formative assessment scores related to grade level skills. Also, Seesaw allows teachers

to provide feedback to students (see Figure 3).

Figure 2. Student assessment scores of first grade skills (in Seesaw)

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

19

Figure 2. Examples of teacher feedback in Seesaw.

During interviews, teachers gave multiple examples of using Seesaw for formative data

to inform instruction and to identify where students’ learning was at in the learning process.

Comments reflecting this include: 1) teacher discussing reading fluency, “...they know how to

record their reading, so that’s when I’m in there going OK, this person can”, 2) when discussing

Seesaw uploaded work, “it gives me a chance to see if students are able to understand what they

are supposed to be doing”, and 3) a very powerful statement about Seesaw, “it’s like having

another teacher in the room”. Another teacher showed me a math problem being explained with a

solution that differed from the solving process modeled in the classroom, the teacher

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

20

commented, “this is a very clear way to assess your students’ learning, you don’t really get to see

what - but Seesaw gives you a chance.”

A second conclusion, specific to this case study, is that the Apple consultant and support

for the district and these schools is a valuable resource, but under-utilized by teachers. When

interviewees were asked how administration could better support their use of technology, twelve

responses asked for additional professional development. When I observed scheduled team

meetings with the Apple consultant (Tina), I recorded that three of the five schools showed a

lack of engagement, little preparation in advance of meetings by teachers, and poor attendance.

School B did not utilize Tina for team meetings during her scheduled time at the school; all

meetings were scheduled on a needs basis by individual teachers. The only exception was School

C; this building maximized their time with Tina, working to redesign traditional lessons in their

classrooms. They were also working to be an Apple Distinguished School. Fourteen of sixteen

interviewees voluntarily shared that they had received valuable support from Tina in

implementing technology in their classrooms (there was not a specific interview question about

Tina or Apple support). Interviewee comments reflect this valuable support, “And I love Tina

because every time Tina comes to our building and she’s showing us one little bit at a time. I

know she has lots in her umbrella but she’s listening to us and give us one little goal at a time to

try.”

A third conclusion is that teachers need a compelling why to seek out training and

professional development, especially veteran teachers who have had classroom success in the

past, in order to pursue their own learning. Sinek (2011) argued the “why” provides purpose.

Teachers at School D had success without technology for several years on math and reading

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

21

standardized tests. Without a clearly identified “why”, these teachers struggled to invest the time

needed for successful technology integration. On the contrary, the principal at School C had a

vision for the building and held staff accountable to integrate technology into their classroom

lessons and routines. All five teachers interviewed at School C acknowledged the role of their

principal when asked about their preparation to use technology in the classroom and when asked

what goals they have around technology. Their principal has established a clear “why” for these

teachers. One interviewee commented, “she did push us a lot but sometimes, people need to be

pushed. As a STEM school, we have to use technology in our classrooms.” Without a shared

vision or purpose, it is understandable that busy teachers will not engage in monthly team

meetings for the technology training they know would be beneficial. The lack of shared goals for

the iPad and Seesaw between buildings leads to the question of who is responsible for

establishing a compelling why, the building principal or district leadership?

Teachers in this study believe iPads create equitable chances for all students. All sixteen

interviewees responded “yes” when asked if technology creates more equitable chances. On the

survey, 22 of 25 respondents agreed with the statement “I believe digital learning creates a more

equitable classroom.” Teachers provided several examples where they identified how iPads and

technology were used to provide equitable chances. One teacher stated, “...everybody gets to do

the work, everybody gets the work done, just in different ways based on their abilities, so I think

that’s equity.” Another teacher discussed varying reading abilities in the classroom and the role

technology plays, “...others that can’t read, they can understand, those who can’t read, it’s being

read to them. So then they get a chance at really knowing what the story is about.” One

interviewee discussed the value in having equal opportunities with the technology, “...they are all

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

22

given a chance. All kids have a chance to become proficient in using the iPads and computers, I

think this is very important.” Other teachers commented on the audio/visual aspects that assist

students with learning differences. The ability of students to dictate on iPads instead of typing

was also noted by several respondents. These results lead to the question, does the lack of

consistent iPad use in the district lead to inequities? Districts may need to consider what digital

learning experiences all students should have in the classroom to avoid increasing the digital

divide.

A fifth result is that successful use of iPads and Seesaw for formative assessment requires

focused, purposeful and ongoing training. “It’s like so much potential and then frustration that

I’m just not there” - I sensed this frustration even with the most techy teachers. Several

interviewees identified a need for collaboration with other teachers using technology or

“providing time for teachers to share ideas.” Hattie (2016) found that collective teacher efficacy

is the top influencer on student achievement. In other words, if teachers have a collective and

collaborative belief in their work together, they will have an impact on learning. Given time to

collaborate and share ideas related to digital learning, the frustration felt by teachers may decline.

I witnessed teachers effectively using iPads and Seesaw, but they were doing so in isolation;

training and professional development should be designed to allow the sharing of these ideas and

practices.

In addition to training, the district can work to remove barriers. In this case study, having

grade level standards preloaded into Seesaw would be beneficial to classroom teachers. Training

could then be provided on aligning Seesaw assignments to these standards. Barriers in the form

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

23

of technical challenges is an ongoing issue in most settings; but collaborative sharing might help

teachers troubleshoot common issues.

Lastly, the final conclusion is that teachers who are willing to put in the extra time have

the most success with technology in their classrooms. Based on the interview data, the teachers

who acknowledged the extra time spent outside of school to learn apps, to redesign assignments,

to utilize online tools in their lessons, and to respond to student work online were the teachers

finding greater success with technology in their classrooms. The term “on my own time” was

used by six respondents and these two comments reflect the commitment of these teachers, “I’m

spending six hours on the weekend trying to figure something out” and “I want to enjoy my

weekends but this is my job.” And some teachers are not willing or able to spend this type of

time, “It’s just too much work.” Using technology is a significant change in our classrooms and

it was observed in this study that in order to champion digital learning, extra time and effort were

required.

Limitations

A limitation of this study included added time for district approval to conduct the study. I lost six

weeks from my original plan. I was still able to complete my targeted number of interviews and

observations. Another limitation was that School B decided to take a “tech break” in March

while technology took a “back seat to other issues in the building.” I was able to conduct two

interviews in this building but did not attend any team meetings or conduct any formal classroom

observations. And lastly, my interaction was limited to the teachers that volunteered to complete

the survey, be interviewed, and have their classrooms observed. For the most part, non-techy

teachers did not attend team meetings or volunteer to participate in this study. I was able to

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

24

interview four teachers that were skeptical of technology and/or were limited users, so I was able

to capture this perspective.

Conclusion

In conclusion, like other aspects of our lives, technology can improve everyday tasks, increase

efficiency and meet our learning individual needs. The same can be said for classrooms. We will

not be going back to a time when technology was not in our schools, as one teacher stated, “I’m

always very pro-tech. It’s just, when you are teaching 21st century learners, you have got to be -

it’s not up to me.”

Teachers, when trained and provided with clear direction, can use Seesaw app in

elementary classrooms to collect formative assessment data and they can use the technology to

create more equitable classrooms.

References

Barron, B., Cayton-Hodges, G., Bofferding, L., Copple, C., Darling-Hammond, L., & Levine, M.

(2011). Take a giant leap: A blueprint for teaching young children in the digital age. The

Joan Ganz Cooney Center and Stanford University. Retrieved from

http://www.joanganzcooneycenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/01/jgcc_takeagiantstep1.

Beatty, I. D., & Gerace, W. J. (2009). Technology-enhanced formative assessment: A

research-based pedagogy for teaching science with classroom response technology.

Journal of Science Education and Technology, 18( 2), 146-162.

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

25

Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2001). Inside the black box: Raising standards through classroom

assessment. Phi Delta Kappan, 80( 2), 139-144.

Bransford, J. D., Brown, A. L., & Cocking, R. R. (2000). How people learn: Brain, mind,

experience and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

Couros, G. (2015). The innovator’s mindset: Empower learning, unleash talent, and lead a

culture of creativity. San Diego, CA: Dave Burgess Consulting.

Creswell, J. W. (2014). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods

approaches (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Darling-Hammond, L, Zielezinski, M., & Goldman, S. (2014). Using technology to support

at-risk students’ learning. Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. Retrieved

from

https://edpolicy.stanford.edu/sites/default/files/scope-pub-using-technology-report.pdf

Hattie, J. (2012). Visible learning for teachers: Maximizing impact on learning. New York:

Routledge.

Hattie, J. (2016). Visible learning for literacy, grades K-12: Implementing the practices that

housand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

work best to accelerate student learning. T

Hunt, E., & Pellegrino, J. W. (2002). Issues, examples and challenges in formative assessment.

New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2002(89), 73-85. doi: 10.1002/tl.48

Lacey, C., Gunter, G. A., & Reeves, J. L. (2014). Mobile technology integration: Shared

experiences from three initiatives. Distance Learning, 11( 1), 1-8.

Marzano, R. (2007). The art and science of teaching: A comprehensive framework for effective

instruction. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

26

Mohammed, S. (2017). Personalized learning and equity: The means or the end? Brookings

Institution. Retrieved from

https://www.brookings.edu/blog/brown-center-chalkboard/2017/06/16/personalized-learn

ing-and-equity-the-means-or-the-end/

Partnership for 21st Century Skills. (2016). Framework for 21st century learning. Retrieved

from http://www.p21.org/storage/documents/docs/P21_framework_0816.pdf

Puentedura, R. R. (2013, May 29). SAMR: Moving from enhancement to transformation [Web

log post]. Retrieved from http://www.hippasus.com/rrpweblog/archives/000095.html

Popham, W. J. (2008). Transformative assessment. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision

and Curriculum Development.

Reeves, J. L., Gunter, G. A., & Lacey, C. (2017). Mobile learning in pre-kindergarten: Using

student feedback to inform practice. Educational Technology & Society, 20(1), 37-44.

Shields, J. (2017). Virtual toolkit. Screen Education, 85, 108-109.

Sinek, S. (2011) Start with why: How great leaders inspire everyone to take action. New York:

Penguin.

Warschauer, M., Knobel, M., & Stone, L. (2004). Technology and equity in schooling:

Deconstructing the digital divide. Educational Leadership, 18(4), 562-588.

Yin, R. K. (2018). Case study research and applications: Design and methods (6th edition). Los

Angeles: Sage Publications.

© 2019 Trish Harvey All Rights Reserved

You might also like

- Nun The Keepers NetflixDocument2 pagesNun The Keepers NetflixMARIANA ISABEL PEINADO NAVARRONo ratings yet

- Disturbed Speaking DiapositivasDocument1 pageDisturbed Speaking DiapositivasMARIANA ISABEL PEINADO NAVARRONo ratings yet

- Dewaele Alfawzan 2018Document25 pagesDewaele Alfawzan 2018MARIANA ISABEL PEINADO NAVARRONo ratings yet

- Free TimeDocument12 pagesFree TimeMARIANA ISABEL PEINADO NAVARRONo ratings yet

- An Empirical Investigation of Foreign Language Anxiety in Pakistani UniversityDocument12 pagesAn Empirical Investigation of Foreign Language Anxiety in Pakistani UniversityMARIANA ISABEL PEINADO NAVARRONo ratings yet

- Book4joy - Cambridge English Preliminary 7 With Answers (1) - Pages-27-33,47-53Document14 pagesBook4joy - Cambridge English Preliminary 7 With Answers (1) - Pages-27-33,47-53MARIANA ISABEL PEINADO NAVARRONo ratings yet

- The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeFrom EverandThe Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck: A Counterintuitive Approach to Living a Good LifeRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (5796)

- Shoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeFrom EverandShoe Dog: A Memoir by the Creator of NikeRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (537)

- Hidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceFrom EverandHidden Figures: The American Dream and the Untold Story of the Black Women Mathematicians Who Helped Win the Space RaceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (895)

- The Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)From EverandThe Yellow House: A Memoir (2019 National Book Award Winner)Rating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (98)

- On Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealFrom EverandOn Fire: The (Burning) Case for a Green New DealRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (74)

- Never Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItFrom EverandNever Split the Difference: Negotiating As If Your Life Depended On ItRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (838)

- The Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingFrom EverandThe Little Book of Hygge: Danish Secrets to Happy LivingRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (400)

- The Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerFrom EverandThe Emperor of All Maladies: A Biography of CancerRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (271)

- Grit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceFrom EverandGrit: The Power of Passion and PerseveranceRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (589)

- A Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryFrom EverandA Heartbreaking Work Of Staggering Genius: A Memoir Based on a True StoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (231)

- Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnFrom EverandTeam of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham LincolnRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (234)

- Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaFrom EverandDevil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New AmericaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (266)

- Elon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureFrom EverandElon Musk: Tesla, SpaceX, and the Quest for a Fantastic FutureRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (474)

- The Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersFrom EverandThe Hard Thing About Hard Things: Building a Business When There Are No Easy AnswersRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (345)

- The World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyFrom EverandThe World Is Flat 3.0: A Brief History of the Twenty-first CenturyRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (2259)

- The Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaFrom EverandThe Unwinding: An Inner History of the New AmericaRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (45)

- The Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreFrom EverandThe Gifts of Imperfection: Let Go of Who You Think You're Supposed to Be and Embrace Who You AreRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1091)

- The Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)From EverandThe Sympathizer: A Novel (Pulitzer Prize for Fiction)Rating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (122)

- Her Body and Other Parties: StoriesFrom EverandHer Body and Other Parties: StoriesRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (821)

- Assignment 2 Sem 1Document6 pagesAssignment 2 Sem 1d_systemsugandaNo ratings yet

- Catering SorsogonDocument102 pagesCatering SorsogonDustin FormalejoNo ratings yet

- Performance: Task in MarketingDocument4 pagesPerformance: Task in MarketingRawr rawrNo ratings yet

- Motoniveladora - G730Document6 pagesMotoniveladora - G730JorgeluisSantanaHuamanNo ratings yet

- Recover at Work Plan 5 ProposedDocument2 pagesRecover at Work Plan 5 ProposedSiosiana DenhamNo ratings yet

- Research Journal of Internatıonal StudıesDocument16 pagesResearch Journal of Internatıonal StudıesShamsher ShirazNo ratings yet

- 10251company Profile PDFDocument3 pages10251company Profile PDFkavenindiaNo ratings yet

- National Policy Paper - Norway (10.03.2019)Document12 pagesNational Policy Paper - Norway (10.03.2019)simoneNo ratings yet

- MLX91208 Datasheet Melexis PDFDocument19 pagesMLX91208 Datasheet Melexis PDFTrần LinhNo ratings yet

- Etf 52 3 30-37 0 PDFDocument8 pagesEtf 52 3 30-37 0 PDFurielNo ratings yet

- Overview of Ventilation CalculationDocument47 pagesOverview of Ventilation CalculationDixter CabangNo ratings yet

- Martin2019 Article BusinessAndTheEthicalImplicatiDocument11 pagesMartin2019 Article BusinessAndTheEthicalImplicatihippy dudeNo ratings yet

- Sairam Vidyalaya: To Study The Collision of Two Balls in Two DmensionsDocument14 pagesSairam Vidyalaya: To Study The Collision of Two Balls in Two DmensionsAditya VenkatNo ratings yet

- National Comprehensive Agriculture Development Priority Program 2016 - 2021Document45 pagesNational Comprehensive Agriculture Development Priority Program 2016 - 2021wafiullah sayedNo ratings yet

- Microservice PatternDocument1 pageMicroservice PatternHari Haran M100% (1)

- Ti ArgusDocument54 pagesTi ArgusVio ViorelNo ratings yet

- TK Series Magnet Tracker PDFDocument21 pagesTK Series Magnet Tracker PDFAaron100% (1)

- Nature and Morphology of Ore DepositsDocument7 pagesNature and Morphology of Ore DepositsIrwan EP100% (3)

- Aalco Metals LTD Aluminium Alloy 6063 T6 Extrusions 158Document3 pagesAalco Metals LTD Aluminium Alloy 6063 T6 Extrusions 158prem nautiyalNo ratings yet

- Monsters of Hyrule For D&D 5e: Master Cycle ZeroDocument33 pagesMonsters of Hyrule For D&D 5e: Master Cycle ZeroNihl ArtsNo ratings yet

- AAA ServersDocument25 pagesAAA ServersKalyan SannedhiNo ratings yet

- NIACL Placement Paper Whole Testpaper 46551Document12 pagesNIACL Placement Paper Whole Testpaper 46551Raja SekharNo ratings yet

- Offer Letter Bigfoot Retail - Sumit KumarDocument2 pagesOffer Letter Bigfoot Retail - Sumit KumarSumit KumarNo ratings yet

- ITCE419 - Final ExamDocument5 pagesITCE419 - Final ExamKANSNNo ratings yet

- HowToBuildAStockStrategy - Portfolio123Document36 pagesHowToBuildAStockStrategy - Portfolio123life_enjoy50% (2)

- IntentsDocument6 pagesIntentsIndunil RamadasaNo ratings yet

- A Review of Programmable Logic Controllers in Control Systems EducationDocument10 pagesA Review of Programmable Logic Controllers in Control Systems EducationHondaMugenNo ratings yet

- Mathematics Form 1 Chapter 1-5 PDFDocument50 pagesMathematics Form 1 Chapter 1-5 PDFAinul Syahirah Omar84% (19)

- Controles de Mod GTA VDocument2 pagesControles de Mod GTA VUNACHNo ratings yet

- Shao2018 PDFDocument232 pagesShao2018 PDFbichojausen0% (1)